In the quiet pre-dawn blackness of November 28th, 1944, something immense slipped through the waters off the coast of Japan, it moved like a phantom, a ghost of impossible scale, displacing over 70,000 tons of the cold Pacific. This was the Shinano, the largest, most powerful aircraft carrier the world had ever seen.

and her very existence was a secret whispered only in the highest echelons of the Imperial Japanese Navy. She was a Leviathan born of desperation, a steel fortress believed by her creators to be nearly unsinkable. But beneath the waves, another shadow was moving. The American submarine USS Archer Fish prowled the depths, its crew entirely unaware of the historic prize that had just appeared on their radar.

They only knew that the silhouette was colossal, larger than any warship they had ever tracked. A jewel was about to unfold between the world’s biggest carrier and a lone submarine. A battle that should have been a foregone conclusion. How did this top secret super ship, Japan’s Great Hope, end up on the ocean floor during her very first voyage? The answer is a story of ambition, haste, and a series of fatal miscalculations that began long before she ever touched the sea.

Shinano’s story begins not as a carrier, but as a battleship, she was laid down on May 4th, 1940. Destined to be the third sister in the legendary Yamato class, the most heavily armed and armored battleships ever conceived. Alongside her siblings, the Yamato and Mousashi, she was meant to be the ultimate expression of Japan’s naval doctrine.

A fleet centered around big guns that could dominate any adversary in a decisive surface battle. Her hull was a masterpiece of heavy engineering with an armored belt over 16 in thick in places, designed to shrug off naval shells and torpedoes like they were pebbles. For two years, the workers at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal toiled to bring this Goliath to life, forging steel plates so massive they dwarfed the men who handled them.But then came June of 1942 and the turning point of the Pacific War, the Battle of Midway. In a single catastrophic battle, Japan lost four of its most experienced fleet carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiyu. The loss was devastating. It wasn’t just the ships. It was the hundreds of seasoned pilots and air crew who went down with them.

The age of the battleship was over, and the age of the aircraft carrier had arrived with brutal clarity. Suddenly, Japan’s naval planners faced a new, desperate reality. They didn’t need another super battleship. They needed to replace their lost carriers, and they needed to do it now. This is where Shinano’s fate took a dramatic turn.

Her partially constructed hull, already a symbol of immense national pride and investment, presented a unique opportunity. The Imperial Japanese Navy made a radical decision. Convert her into an aircraft carrier. This was no simple refit. The challenge was immense, almost as complex as starting from scratch. They were grafting the heart of a modern air base onto the bones of a sea dragon built for a different kind of war.

The process would take another 2 years, a period plagued by constant material shortages and the growing threat of American air raids which were beginning to reach the Japanese home islands. The very nature of her original design meant Shinano could never be a conventional fleet carrier. Her battleship hull was too far along to accommodate the spacious multi-level hanger decks found on ships like the American Essex class or even Japan’s own Shokaku class carriers.

Instead, Japanese designers envisioned something entirely new for her, a massive, heavily armored support carrier. She was to be a floating fortress, a mobile resupply depot that would shadow the main carrier fleet. Her primary mission wouldn’t be to lead the charge, but to sustain it. She would carry reserve aircraft, mountains of fuel, and tons of munitions to replenish other carriers during long, grueling battles.

She would be the logistical backbone of the fleet, a role that was less glamorous but absolutely essential. Her unique design reflected this specialized purpose. She had just a single cavernous hanger deck, but it was heavily protected enclosed within the original battleship’s armored citadel. Her flight deck, while enormous, was slightly shorter than on other large carriers, as her main role was servicing and rearming planes, not launching massive offensive strikes of her own.

Still, she was a behemoth, measuring approximately 872 ft in length, and displacing nearly 70,000 tons when fully loaded. She dwarfed every other carrier of the Second World War. To protect this floating island, she was bristling with defenses, 16 5-in dual-purpose guns, and over 100 anti-aircraft cannons designed to throw up a wall of steel against any incoming attack.

Yet, for all her size and strength, Shinano was a child of haste. As Japan’s fortunes in the war deteriorated, the pressure to finish herbecame overwhelming. The defeat in the Philippine Sea in mid 1944, another disastrous loss for the Navy, accelerated her construction timeline. Corners were cut, shortages of skilled labor and highquality steel meant that many systems were incomplete or substituted with lesser materials.

Welding was often shoddy, and many of the internal watertight compartments, so crucial for a warship’s survival, were not properly sealed or tested. These small compromises, born of desperation, were weaving a fatal flaw into the very fabric of the ship. One of the most remarkable aspects of Shinano’s story is the veil of secrecy that surrounded her.

Her construction at Yokosuka was hidden behind a towering fence, and the thousands of workers were effectively confined to the naval yard, forbidden from ever speaking about the giant they were building. The secrecy was so successful that for decades the allies had no idea she even existed. No official photographs of Shinano were ever released.

The only known images from her lifetime are a few clandestine snapshots. One taken from a Japanese aircraft to inspect her camouflage pattern and another captured by a high-flying American B29 bomber that happened to pass overhead. Its crew likely unaware of the true significance of the blurry shape below. This secrecy was a strategic necessity.

If the Americans learned of this super carrier, she would immediately become a priority target. Japan’s high command envisioned her as a trump card, a surprise weapon to be unveiled in the final decisive battle for the homeland. She was designed to carry not just replacement aircraft, but also the new desperate weapons of 1944, the rocket powered ochre kamicazi gliders.

In essence, she was a mobile base for both defense and suicide attacks, a lynch pin for Japan’s final stand. But scholars still debate whether this hybrid design was a stroke of genius or a fatal compromise. Was she a brilliant adaptation to new realities or was she a ship that tried to do too much and ended up mastering nothing? By late 1944, the war was closing in.

American B-29s were beginning to bomb the Japanese mainland, and the Yokosuka naval arsenal was now within their reach. The thought of Shinano being destroyed in her dock by a surprise air raid was a nightmare for Japanese leaders. The decision was made. She had to be moved. She would undertake a dangerous voyage to the much safer Kuray Naval Base in western Japan to complete her fitting out and final sea trials.

It was a calculated risk, a dash through waters now heavily patrolled by American submarines. But in their minds, the risk of staying put was even greater. If this story resonates with you, feel free to share your thoughts below. On November 19th, 1944, with little fanfare, Shinano was officially commissioned at Yokosuka.

Her command was given to Captain Toshio Abbe, a seasoned and respected naval officer. But as he walked the vast echoing decks of his new ship, a deep sense of unease must have settled upon him. The carrier was a beehive of frantic activity. Hundreds of civilian yard workers were still crawling over her, installing electrical wiring, fitting pipes, and finishing vital systems.

He could see that many of her watertight doors, the essential barriers that stop flooding from spreading, were either not yet installed or had never been tested. Critical pumps and damage control equipment were missing. The ship was a giant but a fragile one. Captain AB pleaded with his superiors for more time.

He knew, with the instinct of a career seaman, that taking this vessel to sea in its current state was a gamble of the highest order. He needed weeks, if not months, to conduct proper sea trials, to train his crew, and to ensure every system was fully operational. But the Navy high command was unyielding. The threat of an American air raid on the Yokosuka shipyard loomed too large in their minds.

To them the danger of an unfinished ship at sea was preferable to the certainty of a finished ship being destroyed at its moorings. Shinano they ordered must sail for the safety of Kore immediately. The final days were a blur of chaotic preparation. The crew of roughly 2,000 sailors, many of them as green as the ship itself, worked alongside the civilian technicians, into her massive hanger.

They loaded not her own airwing. She had none yet, but a deadly cargo of 50 Yokosuka MXY7 Oka kamicazi planes. These were essentially human piloted rocket bombs, desperate weapons for a desperate time. Alongside them were several Shinoyo suicide boats, small motorboats packed with explosives. For her maiden voyage, the world’s greatest aircraft carrier was acting as little more than a transport ferry for specialized weapons, a testament to the hurried and ill- fated nature of her one and only mission.

At 6:00 on the evening of November 28th, Shinano was declared ready. Under the cloak of darkness, she slipped her moorings and glided out of Yokosuka Bay. There was no ceremony, nocheering crowds, just the silent imposing silhouette of the ship disappearing into the night, flanked by her three destroyer escorts, the Yuki Kaz, Isocaz, and Hamakaz.

Once clear of the bay, Captain Abbe set a southwesterly course, pushing his ship to a steady 20 knots, roughly 23 mph. He ordered a zigzagging pattern to make her a more difficult target for any lurking submarines. All lights were extinguished and lookouts strained their eyes, scanning the black churning waves. They were in hostile waters, and every man on board knew it.

The first sign of trouble came around 10 that night. A lookout on Shinano’s bridge, spotted the unmistakable shape of a submarine’s conning tower, silhouetted for a moment against the moonlight. One of the escorts, the esocaz, immediately peeled away, charging toward the contact to attack. But Captain Abbe was wary. American submarines often worked in packs, and he suspected this might be a decoy, a lure to draw his escorts away while the real threat lined up an attack. He made a fateful decision.

He recalled the destroyer and ordered Shinano to turn away, increasing her speed to try and outrun the submarine. This remains a point of debate among naval historians. Was Abbe’s caution prudent, or did he miss a crucial opportunity to eliminate the threat when he had the chance? For a time, it seemed his gamble might have paid off.

The massive carrier surged through the water, leaving the distant submarine behind, but Shinano’s rushed construction was about to betray her. Just before midnight, a bearing in one of her main propeller shafts began to overheat. a mechanical flaw that would have been caught and fixed during proper sea trials.

She was forced to reduce speed, dropping from a brisk 20 knots down to 18. It was a small change, but a critical one. 18 knots was roughly the same top speed as the American submarine that was tenaciously pursuing her. The USS Archer Fish, commanded by Joseph Enlight, now had its chance. The Predator was no longer being outrun. it could keep pace with its colossal prey.

For hours, Enright skillfully shadowed Shinano, staying just outside the range of her lookouts, waiting patiently for the perfect moment to strike. That moment arrived in the early hours of November 29th. As Shinano executed a wide, pre-planned zigzag maneuver to the south, she inadvertently turned her massive slab-like side directly toward the lurking submarine.

It was the shot of a lifetime. At 3:15 in the morning, from a distance of just under a mile, Commander Enright gave the order. The ArcherFish fired a spread of six torpedoes, then immediately dove deep to escape the inevitable counterattack. Aboard Shinano, the minutes ticked by in tense silence. Then a series of four colossal explosions ripped through the carrier’s starboard side, sending shutters through the entire 8072 ft hull.

The torpedoes struck with devastating precision along a single vulnerable line. The first tore into compartments near the stern, rupturing an empty aviation fuel tank. The second slammed into the hull further forward, crumbling bulkheads and flooding one of the main engine rooms. The third hit a boiler room, and the fourth struck near an air compressor station, compromising yet another damage control center.

In less than 2 minutes, the archer fish had delivered a grievous wound. Critically, all four torpedoes had struck along the seam where the ship’s original battleship armor belt met the newer, lighter armor of the carrier conversion, a known structural weak point. Yet, on the bridge, there was no initial sense of panic.

The crew was new, but they had basic training. The officers, confident in their ship’s immense size and armored protection, believed she could absorb the damage. After all, this was a Yamato class hull. Surely, she was built to withstand far worse than this. Damage control team scrambled into the darkness below decks to fight the flooding.

Counter flooding was ordered on the port side to try and level the ship out. Captain Abbe, assessing the initial reports, felt a wave of cautious optimism. There were no major fires. The explosions, while violent, hadn’t caused a catastrophic chain reaction. 15 minutes after the attack, Shinano was listing about 10° to starboard.

It was serious, but it didn’t seem fatal. Here, Captain Abe made his second critical error of the night. Convinced that the ship was stable and that the submarine was still a threat, he ordered Shinano to maintain her speed of 18 knots, he wanted to get out of the danger zone as quickly as possible.

But plowing ahead through the ocean only forced more water into the gaping holes in her hull. The immense pressure of the sea funneled into the breaches by the ship’s forward momentum overwhelmed the damaged compartments. The flooding which might have been contained instead spread relentlessly. It was a classic tragic dilemma.

Flee the enemy or stop to save the ship. Abe chose to flee, a decisionthat would seal Shinano’s fate. For a short time after the torpedo impacts, it seemed the crew below decks might just win their fight. They counter flooded compartments on the port side and manned the pumps, managing to briefly hold Shinano’s list at around 12°, but the ship’s forward momentum was a relentless enemy.

Waters surged into the damaged sections with immense force, placing unbearable strain on the bulkheads, and here every shortcut taken during her construction came back to haunt her. Every rivet that hadn’t been perfectly sealed, every welded seam that had been rushed by an exhausted worker now became a tiny fatal leak. The watertight compartments which had not been properly pressure tested for leaks began to fail.

Water seeped, then trickled, then poured from one section into the next. A slow, unstoppable cascade of failure deep within the ship’s guts. By 5:00 in the morning, 2 hours after the attack, the situation was becoming critical. Shinano was now listing over 15° and settling noticeably lower in the water.

The optimism on the bridge had evaporated, replaced by a grim understanding. The damage was far worse than anyone had imagined. It was at this point that Captain Abe, realizing his catastrophic error, made a lastditch attempt to save his ship. He ordered a turn toward the coast of Japan’s main island, Honshu, hoping to beach the colossal carrier in the shallow waters off Shino Point before she founded, but it was too late.

The list continued to worsen, passing 20° by dawn. The incoming seawater finally reached and extinguished her remaining boilers. By 7:00, Shannano was dead in the water. All engines silent, drifting helplessly. Her destroyer escorts closed in, doing everything they could to assist. The Hamakazi and Isocazi attempted to pass toll lines, hoping to pull the wounded giant toward shore. But it was a futile gesture.

The destroyers, powerful as they were, were like ants trying to move a mountain. The 70,000 ton carrier, now burdened with thousands of tons of seaater, barely budged. By 900 in the morning, Shinano lost all electrical power, plunging her vast interior into absolute darkness and silencing the last of her pumps.

The end was now inevitable. It was clear to everyone that nothing could save the ship. Captain Arby finally turned his attention from his vessel to his men. Around 10:00, with the list now exceeding a terrifying 30°, he gave the order to prepare to abandon ship. The scene on deck was one of organized chaos.

The huge flight deck was now tilted like a sinking ramp, making any movement treacherous. Crewmen scrambled to deploy life rafts, while others simply prepared to jump into the cold, churning sea. The escorting destroyers moved in perilously close, their own crews ready to pluck as many men from the water as they could. Following the solemn, unbroken tradition of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Captain Toshio Abe chose to remain on the bridge.

He would go down with his ship. Two of his senior officers made the same choice, staying by his side to the very end. The story of Shinano is a powerful reminder of how quickly fortunes can turn in war. If you’re finding value in these forgotten histories, a simple subscribe helps us bring more of them to light.

At 10:57 a.m. on November 29th, 1944, just over 7 hours after the Archer Fish’s torpedoes had found their mark, Shinano’s final moment came, the massive carrier capsized completely to starboard. Her great red hull rolling up towards the sky before she began her final plunge. She slid stern first beneath the waves.

As she went down, a thunderous roar of collapsing steel and imploding compartments echoed across the ocean. A final agonizing groan from the dying Leviathan. For a few unlucky souls still in the water, the powerful suction created by her descent dragged them down with her. In a matter of moments, the pride of the Japanese Navy, the largest warship of her kind, was gone.

The human cost was staggering. Of the roughly 2,515 men on board, including the civilian technicians, about 1,335 souls were lost, including Captain Abe. Just over 1,000 survivors were pulled from the frigid waters by the destroyers. In a final telling detail about the obsession with secrecy, these survivors were not returned to a major naval base.

They were taken to a remote island and quarantined, sworn to silence to prevent news of the disaster from spreading and damaging morale. The loss of Shenano was to remain a state secret. Meanwhile, the USS Archerish had slipped away after firing his torpedoes. Commander Enright had taken his submarine deep to evade the depth charges dropped by Shinano’s escorts.

Listening on their hydrophones, his crew could hear the unmistakable, terrifying sounds of a massive ship breaking up for over 40 minutes. When they cautiously surfaced at daybreak, the ocean was empty. They knew they had sunk something enormous, but they had no idea what it was because Shinano’s existence wasunknown to the Allies.

US Navy intelligence initially credited the Archer fish with sinking a smaller carrier. It was only after the war ended that the astonishing truth was revealed. A single American submarine had on its own destroyed the world’s biggest aircraft carrier. In the end, Shinano’s demise was a lesson written in steel and tragedy.

She was pushed to sea incomplete, her crew was inexperienced, and her captain made critical errors in judgment. Was her sinking the result of one single mistake, or a cascade of them? Historians still debate whether better damage control could have saved her or if her rushed, compromised construction made her fate inevitable from the moment the first torpedo struck.

She was a ship that embodied both Japan’s incredible ambition and its fatal desperation. Conceived as a trump card to turn the tide of the war, she instead became a monument to its unforgiving nature. A ghost ship lost on her very first dawn.

News

“‘Clean This Properly!’ the CEO Roared 😠 — Completely Unaware That the Man in Tattered Clothes Was Keanu Reeves in Disguise, Seconds Before a Corporate Meltdown, a Hidden Takeover Plot, and a Twist So Ruthless and Deliciously Cinematic Erupted That Executives Nearly Fainted From Shock 🏢🔥” Witnesses swear the CEO’s smug bark curdled into sheer panic when the ‘janitor’ lifted his head, triggering whispers of secret audits, undercover missions, and a karmic ambush years in the making

The Man Behind the Rags: A Shocking Revelation In the bustling heart of the city, where ambition thrived and dreams…

“LUXURY STORE ERUPTION 💎 Arrogant Socialite Hurls a Snide Insult at Sandra Bullock—Only for Fictional Keanu Reeves to Deliver a Breathtaking, Ice-Cold Reaction That Stops the Entire Boutique in Its Designer-Heeled Tracks 😱” — In this sparkling fictional meltdown, diamonds aren’t the only things cutting deep as Keanu’s silent glare slices through the tension, leaving the smug woman trembling while stunned shoppers cling to their pearls and gasp for emotional oxygen👇

The Jewel of Deceit In the heart of Beverly Hills, where glamour and wealth intertwine, a lavish jewelry store stood…

Keanu Reeves’ Secret Letter to Diane Keaton — The Quiet Confession That Sat Unread for Years and Rewrote a Hollywood Myth 💌 The narrator leans in with a sly hush as envelopes, dates, and a single sentence ignite whispers of restraint, timing, and a truth never meant for headlines, suggesting the real scandal wasn’t romance but the discipline to let love stay unclaimed until the moment passed forever

The Line Drawn: A Story of Missed Connections In the dazzling realm of Hollywood, where the glow of fame often…

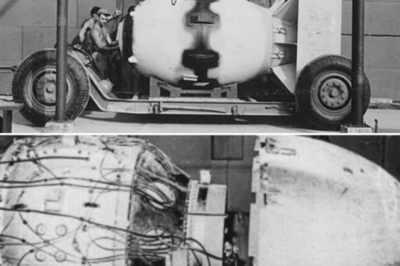

HOW FAT MAN WORKS ? | Nuclear Bomb ON Nagasaki | WORLD’S BIGGEST NUCLEAR BOMB

On August 6th, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The bomb was…

Why This ‘Obsolete’ British Rifle Made Rommel Change Tactics Uncategorized thaokok · 21/12/

April 1941, the Libyan desert outside Tobrook, Owen RML watched his panzas advance toward the Australian defensive perimeter, confident his…

“Inside the Ocean Titanic Recovered: After 80 Years, the Titanic Reassembled Piece by Piece — What They Found Will Shock You!” After 80 years submerged, the Titanic has been fully recovered and reassembled piece by piece, and what experts discovered during the process is far more shocking than anyone could have imagined. Hidden inside the wreckage were cryptic messages, unexplained artifacts, and eerie signs of the ship’s final moments. The Titanic’s restoration reveals a deeper, darker story than we’ve ever been told. The truth about the ship’s fate will haunt you forever

Echoes from the Abyss: The Resurrection of Titanic In the depths of the Atlantic, where shadows linger and whispers of…

End of content

No more pages to load