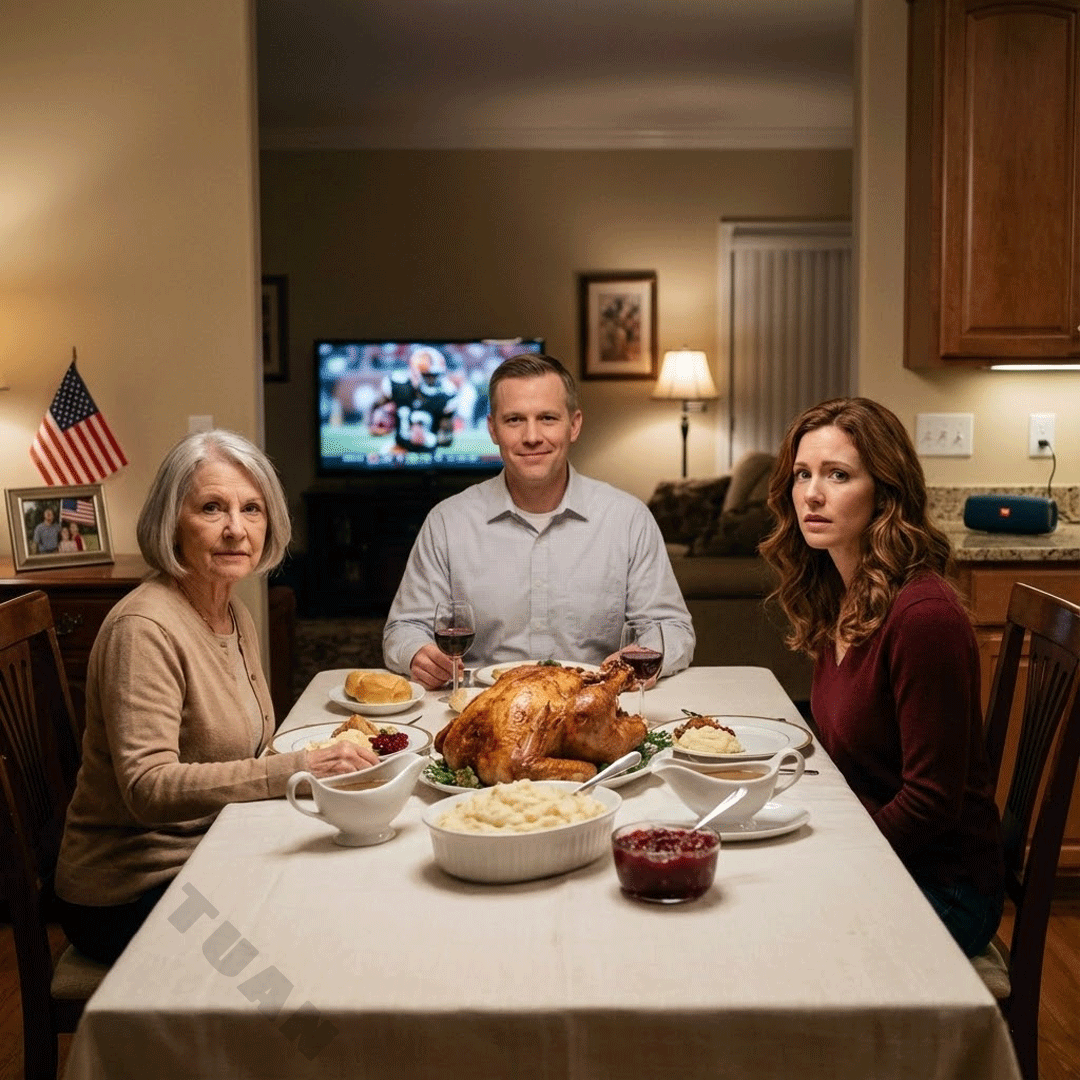

Thanksgiving at my house always started with the same three things: the parade murmuring from the living room television, the smell of turkey skin turning crisp in the oven, and the quiet ache of setting out one extra place in my mind even though the chair stayed empty. Derek used to tease me about that, the way I lined up the forks so the tines all pointed the same direction, the way I folded napkins as if the creases could keep a family from coming apart. After he died, I kept doing it anyway. Tradition is a kind of muscle, and when you lose someone, you either let the ritual collapse or you use it to keep standing.

By noon, the kitchen looked like a small storm had already passed through. Sweet potatoes steamed under foil. Green beans waited in a casserole dish with fried onions sealed in a zip bag. A bowl of cranberry sauce sat on the counter, ridged and glossy, still shaped like the can because Caitlyn used to giggle every year and say it looked like a science experiment. I kept it that way for her, long after she stopped giggling like a kid.

Outside, November in our part of the country had already decided it wanted to act like winter. The yard was dusted with new snow, thin and bright over the brown grass. The maple branches clicked softly in the wind, and the neighborhood looked the way it always did in holiday ads, calm, clean, harmless. It is amazing what a picture can hide.

People think danger arrives loud. They think it announces itself. In my experience, it usually comes carrying a pie.

Jeremy showed up an hour late, as if time itself waited for him. I heard his car door slam, then the crisp stomp of shoes on my porch boards, scraping snow off like he was shaking off inconvenience. When I opened the door, a gust of cold air came in with him and with Sheila, and for a moment my candles flickered in their holders like they were reconsidering their job.

“Mom,” Jeremy said, leaning in for a kiss on my cheek.

His cologne was sharp, expensive, something woodsy that smelled like a magazine sample. His cheek was cold, his mouth warm, the gesture performed quickly, like a box checked. Sheila stood half a step behind him in a camel coat that looked too new to be truly warm.

“Margaret,” she said, smiling wide.

Her smile had always been technically perfect, teeth bright, corners lifted, but it never quite reached her eyes. Sheila’s eyes were the part of her that told the truth, and the truth in them was never affection. It was assessment.

“You made it,” I said, because that is what mothers say when their grown children walk into the home they were raised in. We say it even when they barely do.

Sheila drifted in like my house was a place she visited, not a place that built the man she married. She hung her coat neatly on the rack, smoothed her hair, and glanced around my entryway with that faintly polite expression people wear when they are trying not to look like they are judging. Jeremy followed her, already checking his phone.

Then Caitlyn stepped around them, and the air changed. She hugged me with both arms, tight and real, her cheek pressed to my shoulder for just a second longer than necessary. At seventeen she was all long limbs and guarded softness, tall now, with her hair pulled back by a scrunchie like she was in a hurry to get back to herself. Her eyes, though, were steady. Those eyes looked at me like I mattered.

“Hi, Grandma,” she whispered.

“Hi, honey,” I whispered back, and I meant it.

She smiled and it was small but genuine, then she slipped past into the kitchen as if she wanted to be near the work, near something honest.

The rest of the family arrived in waves. Denise with a covered dish and loud laughter. Cousins with store-bought pies and stories about traffic. Someone’s boyfriend who called me ma’am and looked nervous. People filled the house with noise the way they always do when they are afraid of silence, and for a while I let myself float in it. I poured drinks. I warmed rolls. I nodded at jokes. I smiled at old photos someone had framed on a side table.

If you had been in my living room then, you would have thought it was normal. Maybe a little tense, but families are always a little tense around the holidays. That is what we tell ourselves. It is how we keep coming back to the table even when we know the table is where we get cut.

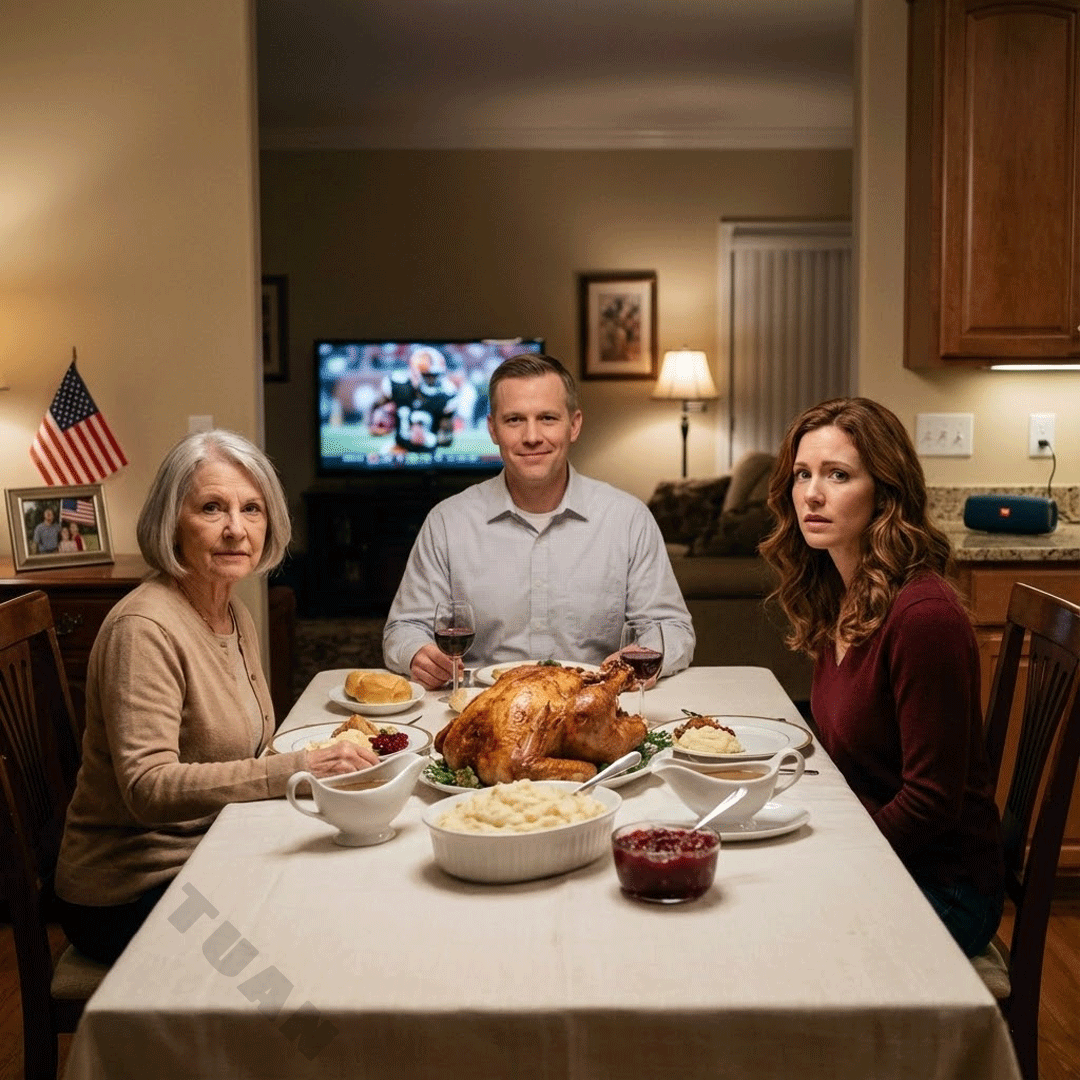

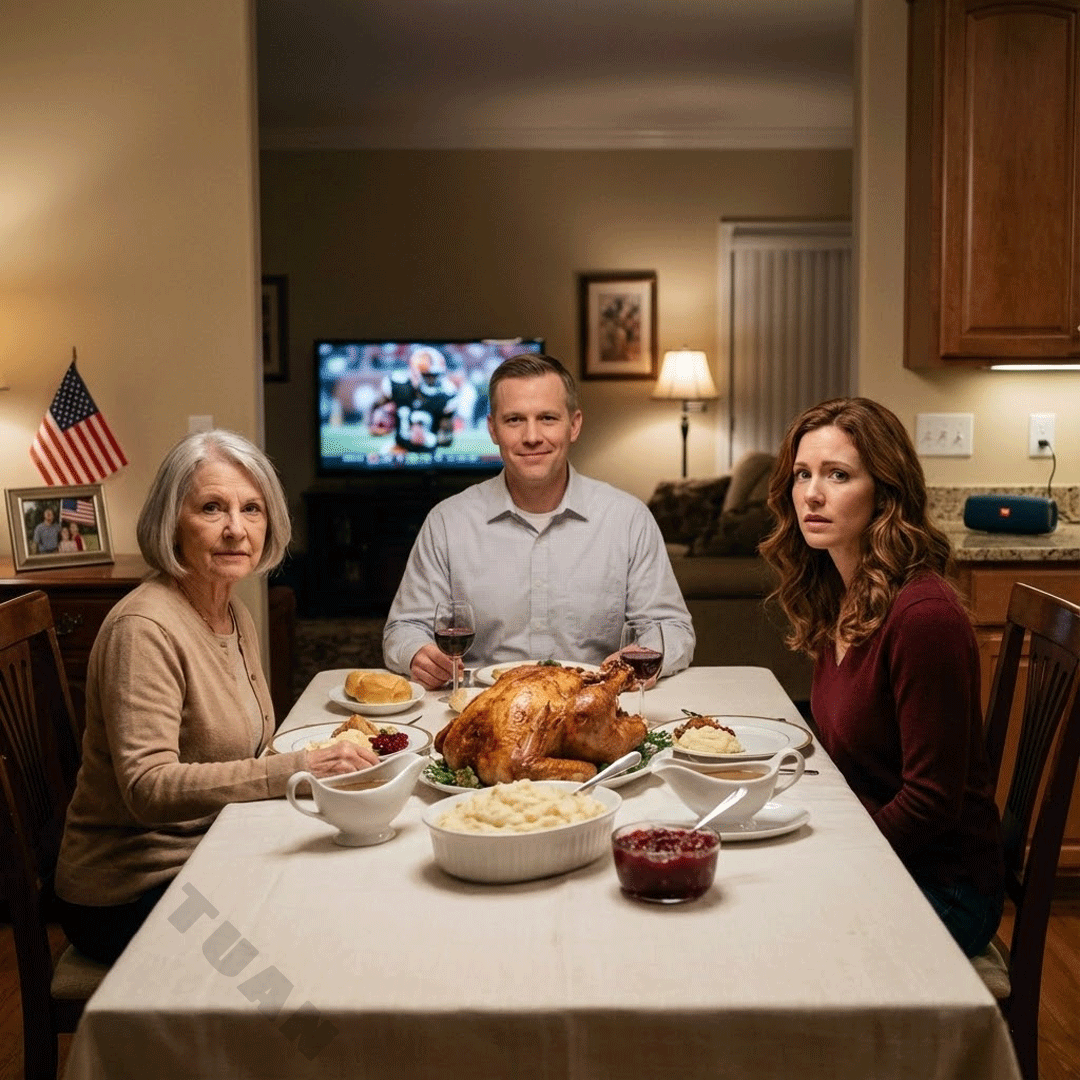

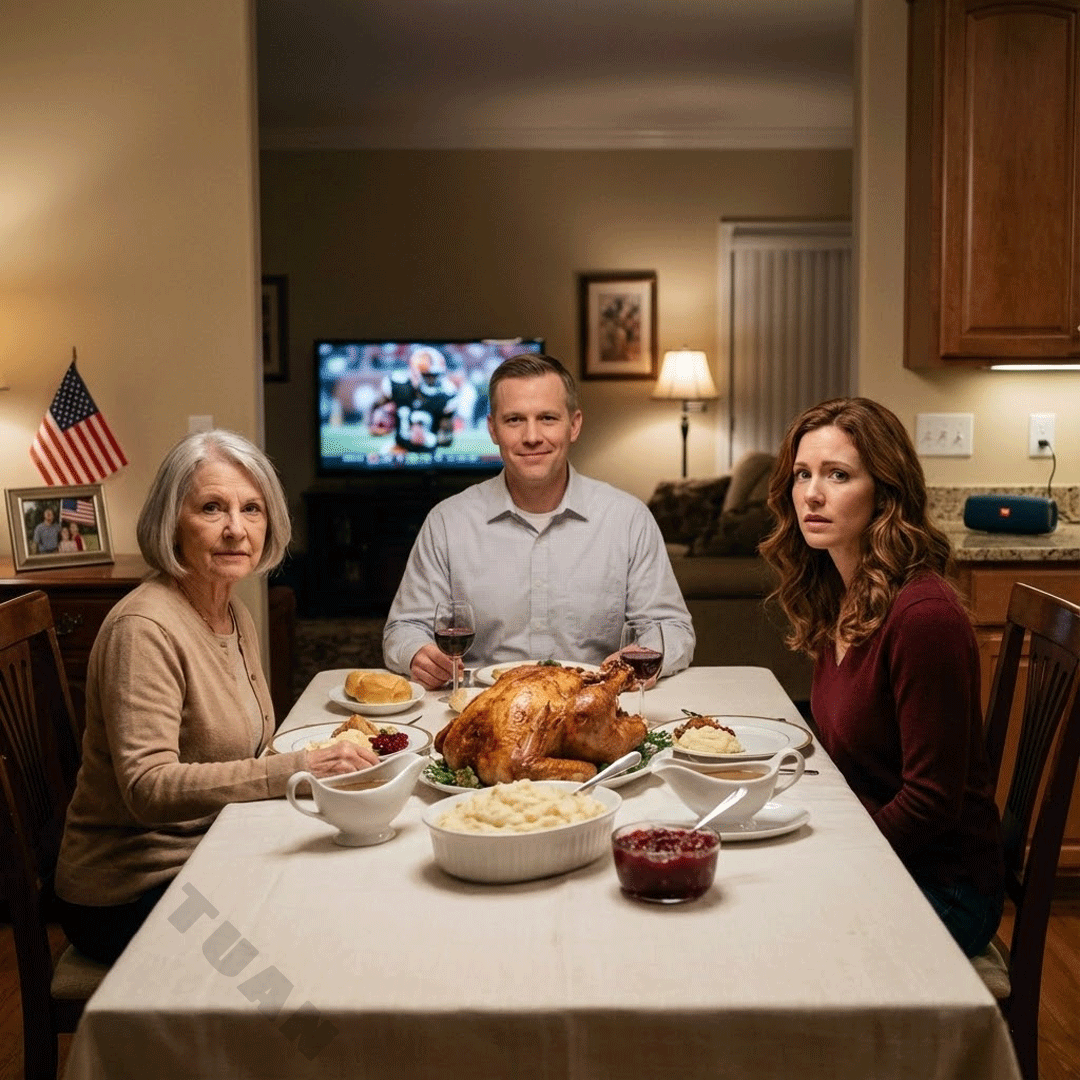

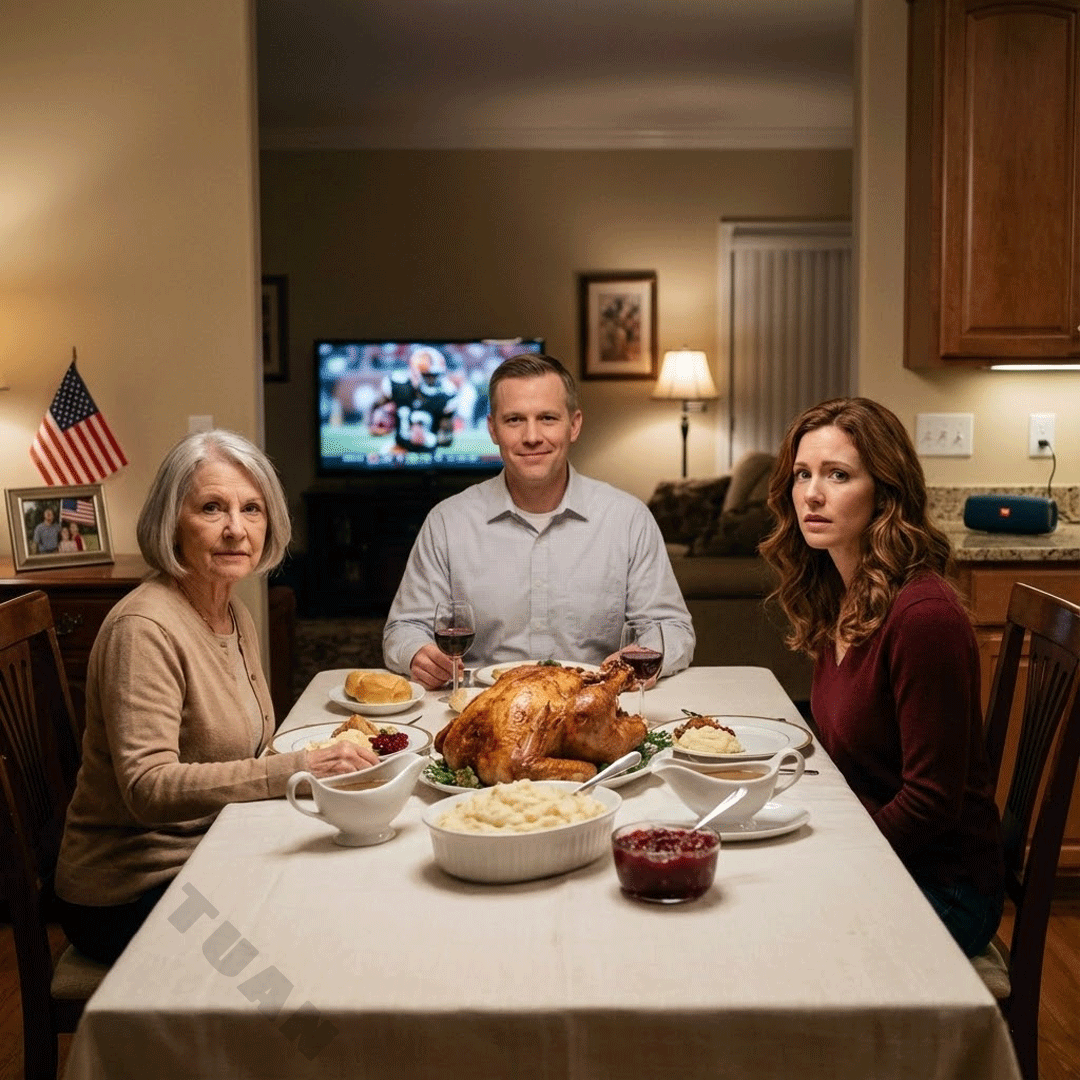

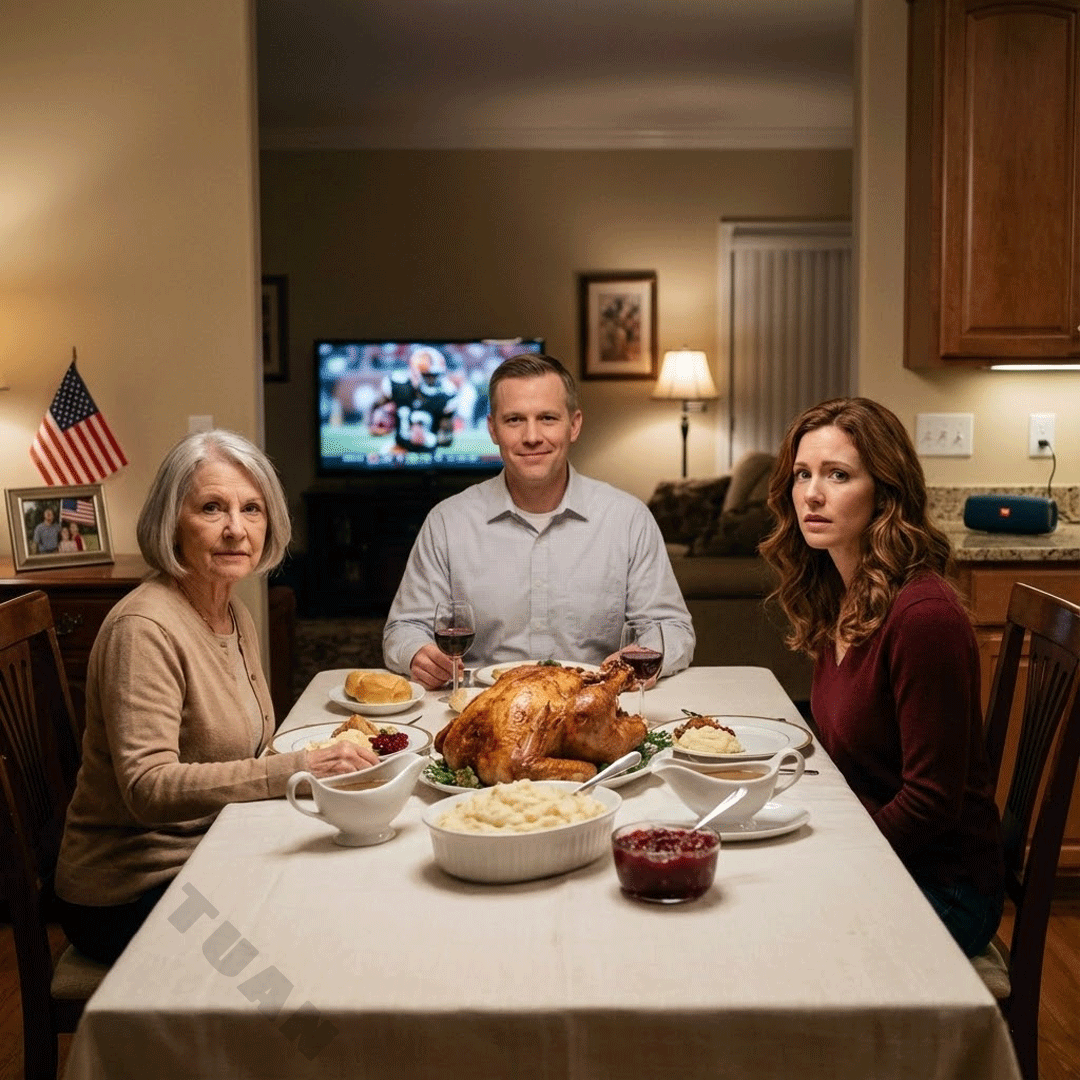

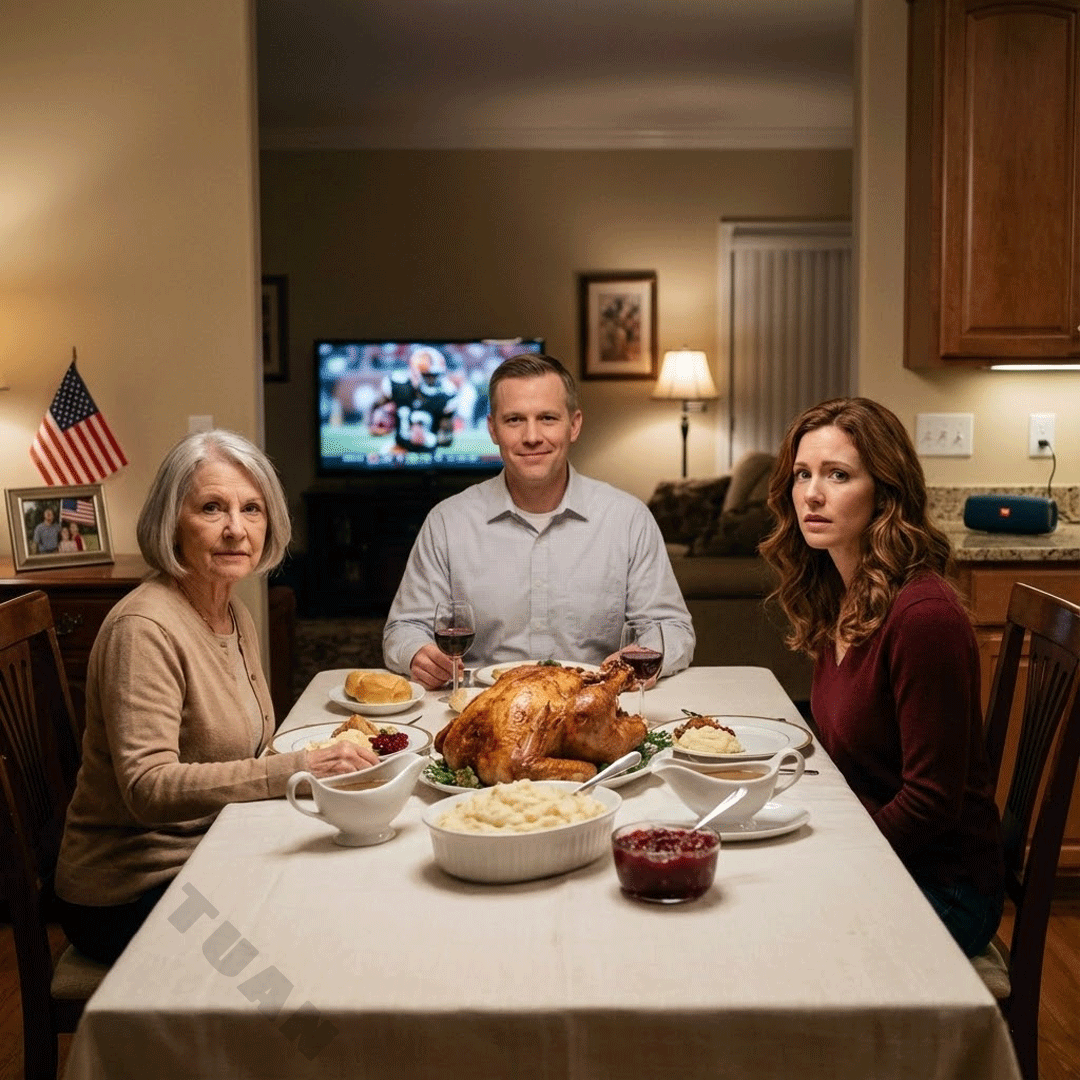

Dinner hit the table in a warm rush. I carried the turkey like a sacred object, the way Derek used to, and the room quieted just enough to respect it. The long oak table was dressed in a linen runner printed with little gold leaves. A few candles burned low in glass holders. My old gravy boat, the one with a tiny chip on the handle, waited beside the cranberry. Paper napkins with cartoon turkeys sat in stacks, partly because I liked them and partly because Caitlyn had once loved them so much I couldn’t stop buying them.

I sat at the head of the table because this was still my house. I had earned that seat with decades of dishes and birthday cakes and nights when I stayed up waiting for Jeremy to come home. Jeremy sat to my right, Sheila beside him. Caitlyn sat across from me, young cousins down the sides, everyone passing bowls, laughing, reaching, clinking silverware against plates.

For the first fifteen minutes, nothing happened. The way nothing happens before something does.

I was mid-sentence, telling Denise about a neighbor’s new puppy, when Jeremy leaned toward me and his voice softened into something that sounded like sweetness.

“Mom,” he said, “try this special gravy I made just for you.”

The words were harmless. The tone was not.

Jeremy smiled too hard when he said it. Not the easy grin of a son proud of something he cooked, but a smile that looked held in place, practiced, like he had rehearsed it in a mirror. His eyes held a glint that was too eager, too focused. His fingers hovered near my plate as if he was waiting for something, as if the air itself was on a timer.

Jeremy had never cared about food. Most years he barely acknowledged what I cooked. He arrived late, ate fast, and retreated into his phone like family was a subscription he forgot to cancel. But tonight he was leaning in, syrupy and attentive, voice warm the way a salesman’s voice is warm.

“I made this one just for you,” he added. “You’ll love it. Promise.”

I didn’t answer. Not immediately. I looked down at the gravy, rich and dark, glossy and thick, pooling over the turkey like melted varnish. It smelled normal, like pepper and drippings, like every gravy I’d made in my life. It looked right.

My body didn’t care that it looked right.

A small tightness spread through my chest, the kind that has nothing to do with asthma and everything to do with instinct. It was the same kind of tightness I’d felt years ago when Derek’s doctor said, We want to run one more test, and I knew before he finished the sentence that our life was about to change.

I glanced at Sheila. She was laughing too loudly at something a cousin said, her hand resting on Jeremy’s arm like a claim. Her plate sat close, almost untouched, the turkey neat, the mashed potatoes pristine.

In my peripheral vision I saw Jeremy watching me, watching my plate, watching the gravy like it was a coin he had just dropped into a machine and was waiting for the prize.

I don’t know what made me do it. I could tell you it was caution. I could tell you it was paranoia. I could tell you it was years of watching Jeremy and Sheila exchange glances when I mentioned my will, my house, my doctor appointments. I could tell you it was the way Sheila’s voice always turned honey-sweet when she suggested I “take it easy” or “let them handle things.” All of those are true.

But the real reason was simpler. Something in the moment didn’t sit right with me, and I have lived long enough to respect that feeling without needing to justify it to anyone.

So I reached over and switched our plates.

I did it casually, like it was a joke, like it was nothing, like I was keeping the vibe light. My fingers slid beneath my plate, then hers. I swapped them in one smooth motion and kept my face neutral, the way you do when you are trying to look harmless.

Sheila didn’t notice. No one did.

No one except Jeremy.

His whole body stiffened, just a fraction, but I saw it. The smile on his face cracked for half a second, and his eyes flicked down to the plates like he’d lost sight of something important.

“Wait, no, Mom,” he said quickly, voice dipping into panic before climbing back into charm. “Uh, that one’s yours.”

I had already taken a bite of Sheila’s mashed potatoes. I chewed slowly, nodded politely, and let my expression stay mild.

“It’s all the same,” I said lightly.

I lifted my water glass like I was toasting the table and turned my attention toward Denise so it looked like nothing had happened. Inside my chest, though, the tightness became a steady, quiet alarm.

Jeremy’s eyes stayed on the plate in front of me too long.

Ten minutes later, Sheila shifted in her chair and pressed her hand to her stomach.

At twenty minutes, she stopped talking.

At thirty minutes, she stood up too fast, swayed, and grabbed the back of her chair as if it was the only thing holding her upright.

“I don’t feel good,” she whispered, and her voice was thin in a room that suddenly went too quiet.

The cousins froze. Denise got up, flustered, reaching for the water pitcher. Someone asked if Sheila needed air. Someone else said maybe she ate something bad. Jeremy’s chair scraped back as he rose, his face snapping into concern so quickly it might have impressed me if I hadn’t just seen it slip.

Sheila’s skin turned pale beneath her makeup. Sweat beaded at her hairline. Her eyes looked glassy and unfocused, the way eyes look when the body is fighting something it cannot explain.

“My stomach,” she said again, and this time she sounded afraid.

Jeremy grabbed his phone. His hands shook, barely, but enough for me to notice. He dialed with the speed of a man who expected this.

The words 911 were spoken. The youngest cousin started crying. The football game in the other room kept playing like nothing was wrong, because the world does not stop for one family’s nightmare.

The paramedics arrived fast, boots thudding on my porch boards, radios crackling, bright jackets flashing against the snow. They moved with practiced calm through my front door, past my framed family photos, into my dining room where the candles were still burning like witnesses.

“Sheila,” one of them said gently, checking her pulse, “can you tell me what you ate?”

Sheila’s eyes rolled toward Jeremy, then toward me. She swallowed hard. Her voice came out in a strained whisper, and it landed in the room like a dropped plate.

“It was the gravy,” she said. “Something in the gravy.”

I looked at Jeremy.

Jeremy looked at me.

Neither of us blinked.

I hadn’t had a reaction. Not a cramp, not a tickle in my throat, not the familiar tightening that usually warned me I’d eaten something I shouldn’t. And I had more allergies than I cared to count. Seafood, nuts, shellac, certain mushrooms, certain medications. At my age you learn to read labels the way teenagers read texts. You learn to sniff before sipping. You learn to ask what’s in something even when people roll their eyes.

Sheila did not have allergies, at least none she’d ever mentioned. Sheila ate anything.

The ambulance lights painted the snow outside in frantic flashes of red as they loaded her onto a stretcher. Jeremy walked beside her with one hand on the rail, his face arranged into worry. A husband’s face. A son’s face. The face he needed.

No one asked how I felt. No one even remembered out loud that Sheila had eaten from my plate. The story formed quickly, smoothly. Sheila got sick. Sheila needed help. Jeremy was the anxious husband doing the right thing.

And I sat at the head of my table, still, while my mind rewound the moment of his too-hard smile.

After the ambulance left, the house emptied in a slow spill. People followed to the hospital or trickled away with awkward hugs and murmured prayers. Denise hugged me and said, Call if you need anything, the way people say it when they mean it but don’t know how to stay.

Jeremy did not hug me.

He did not look back.

I stayed because my body didn’t know what else to do. I cleaned because cleaning is what I do when fear wants somewhere to sit. I stacked plates. I scraped leftovers into containers. I wiped the table until the wood shone again. I folded napkins. I rinsed serving spoons. The work was ordinary, and that ordinariness kept me from tipping into something worse.

No one offered to help. They never did.

The gravy boat was nearly empty. I poured what remained into a mason jar, sealed it tight, and tucked it behind the cranberry jelly in the fridge. It felt strange, putting gravy away like it mattered, but I have lived long enough to understand that evidence often looks like nothing at first.

Then I turned off most of the lights and sat at my kitchen table in the dim yellow glow of the old lamp over the sink. Outside, the snow fell soft and steady. Inside, the air smelled faintly of cinnamon and turkey fat, and something else I couldn’t name.

Something in me had shifted.

Not fear, exactly. Not panic.

It felt like the moment before a storm when the sky turns that heavy gray and the world goes quiet in a way that isn’t peace. It is warning. I’d been blind for too long. I’d let Jeremy and Sheila smile at me with teeth like knives. I’d let them talk about “making things easier” and “having a plan” and “helping Mom out,” while maneuvering around me like I was a piece of furniture they hadn’t decided whether to keep or discard.

Tonight, I saw a crack in the mask.

And for the first time in years, I didn’t feel the urge to patch it.

I didn’t sleep. Not because I was worried about Sheila, though I did wonder if she was okay, but because my mind kept replaying the evening like a tape, searching for the second the lie started. I sat at the table with a notebook in front of me, not to write a story, but to keep my hands busy turning pages. Derek’s old notebook. The one I hadn’t touched since his funeral.

At 2:23 a.m., my phone lit up.

A text from Jeremy.

Still in ER. She’s stable now. I’ll keep you updated.

No thanks for staying. No how are you feeling. No love you. Just a sterile status update, like I was a distant relative he had to notify.

I didn’t reply.

At 3:07, I opened the fridge and took out the mason jar. I held it up to the light. It looked fine. It smelled fine. But when I poured a little onto a saucer and stirred it with a spoon, I saw specks that didn’t look like pepper or thyme.

My stomach went cold in a way that had nothing to do with temperature.

I picked one speck out with a toothpick and stared at it. Too small to identify. Too wrong to ignore. I set it down, washed the spoon, and put the jar back behind the cranberry jelly like I was hiding a secret I wasn’t ready to say out loud.

Morning came thin and pale. The house looked tired in daylight, like it had hosted too much pretending. I made coffee and drank it standing at the counter, staring at my hands. They were steady. They were older, yes, but steady. That mattered to me more than it should have, because I could already hear the words Jeremy and Sheila might use if they needed to.

Confused. Emotional. Forgetful.

Jeremy didn’t call.

Instead, around noon, Caitlyn did.

Her name on my screen tightened my chest. Caitlyn wasn’t a mid-day caller. Calls meant something. Calls meant privacy, urgency, a door closing softly on the other end.

“Grandma,” she whispered when I answered. Her voice sounded small, and she was not small anymore. “I need to tell you something.”

I sat down slowly, as if my body knew to brace before my mind did. “Go ahead, honey.”

There was a pause, and I heard a faint click, like she’d stepped into a hallway.

“I don’t know if I should,” she said. “Maybe it’s nothing. But yesterday, before dinner, I saw Dad in the kitchen with the gravy.”

My throat tightened.

“He was adding something,” she continued, the words coming faster now. “From a little glass bottle, like a dropper. I thought it was spices, but he looked nervous. And when I walked in, he jumped.”

“Are you sure?” I asked, keeping my voice calm for her.

“Yes,” she whispered. “He told me to go set the table. Like I was in the way.”

“Did your mom see?” I asked.

“I don’t think so,” Caitlyn said. “She was upstairs with Aunt Denise. Grandma, I’m scared I’m making it worse, but I can’t stop thinking about it.”

“You did the right thing,” I told her, and meant it. “You did exactly the right thing.”

I heard her exhale like she’d been holding her breath since yesterday.

“Don’t say anything to them,” I added softly. “Not yet. I’ll handle it.”

“Are you okay?” she asked, her voice cracking.

I looked at my kitchen, at the old calendar on the wall, at Derek’s mug on the shelf, at the quiet that had become my companion. “I’m okay,” I said. “And I’m proud of you.”

After we hung up, I sat staring at the wall while my mind pulled old moments out of storage like boxes from a basement. Jeremy last spring, sliding papers across my table with a smile he’d learned in high school when he wanted to distract me from the truth. Sheila’s voice saying, Good, now that’s done, as if she was closing a deal.

I stood and walked to the filing cabinet in the hallway. My knees didn’t creak. My hands didn’t shake. That detail mattered. It was proof, if only to myself, that my body wasn’t betraying me. Only my family was.

I pulled out the envelope Jeremy had given me.

“This is just hospital paperwork, Mom,” he’d said back then. “Power of attorney stuff, just in case. Emergencies. No big deal.”

I hadn’t read it carefully. I trusted him. I raised him. I wiped his nose, taught him to tie shoes, sat up with him through fevers that made his skin burn. I believed history bought loyalty. Sometimes it buys entitlement instead.

I opened the envelope and laid the pages out on my kitchen table.

It wasn’t just medical authorization.

It was a durable power of attorney, notarized, giving Jeremy authority over my finances, property, and decisions if I was deemed medically unfit. The language was broad, slick, designed to sound reasonable until you realized what it allowed.

I flipped to the signature page.

My name stared back at me in shaky cursive.

I hadn’t understood what I signed.

And if that gravy had done to me what it did to Sheila, if I’d ended up in an ER disoriented, vomiting, confused, then what? Who would have declared me unfit? Who would have stepped in “for my own good” and taken over everything?

My stomach went cold, but my mind went clear.

I called my lawyer.

Michael Adams had been our family attorney since Derek’s first will. Sharp mind, calm voice, always in a charcoal suit that looked too expensive for a man whose office paint peeled at the corners. He answered on the second ring.

“Mrs. Reynolds,” he said. “Everything all right?”

“No,” I replied. “And yes. Michael, I need you to look at a document, and I need to revoke it today.”

There was a pause, then his voice shifted, full attention. “Can you come in this afternoon?”

“I’ll be there in an hour,” I said.

Downtown smelled like winter and exhaust and old brick. I parked in my usual spot and walked into Michael’s building without hesitation. He met me in the hallway, serious, and guided me into his office.

He read the document slowly, adjusting his glasses twice, then held up the signature page like it might change if he stared at it hard enough.

“Did you understand what you were signing?” he asked gently.

“No,” I said. “I trusted my son.”

Michael’s mouth tightened, a flicker of something like anger crossing his face before he smoothed it away.

“This is not limited to health matters,” he said. “This gives Jeremy authority over your finances, your property, even decisions about where you live, if someone claims you’re incapable.”

I sat back. “Do you think I’m incapable?” I asked.

Michael studied me, then said quietly, “No. Do you?”

“I drove myself here,” I replied. “I read the Wall Street Journal this morning, fixed my leaky faucet last week, and mailed a chess move to a retired engineer in Florida that’s about to ruin his weekend.”

Michael’s lips twitched into the briefest smile. “You sound fine to me,” he said. Then his voice firmed. “Do you want to revoke this?”

“I do,” I replied. “And I want a new one. I want Caitlyn as my primary agent.”

He blinked. “Your granddaughter.”

“She is the only one who has told me the truth lately,” I said. “She’s seventeen, but she’s not a child where it matters.”

Michael nodded slowly. “Legally, we can structure it,” he said. “We’ll need a backup until she’s eighteen. But yes.”

“Do it,” I said.

We drafted new documents. He read every paragraph aloud. I read them again myself. He didn’t rush me. When it came time to sign, my hand didn’t shake. I signed like a woman putting her name back where it belonged.

Before I left, Michael leaned forward and spoke quietly, the way professionals do when they are trying to keep you from slipping into denial.

“I also recommend a trust,” he said. “If you suspect manipulation, we put your assets beyond reach. It’s not punishment. It’s protection.”

Protection. The word tasted different now. Not soft. Not sentimental. Structural.

“Start it,” I said.

When I got home, the house felt both familiar and altered, like a room after furniture has been moved. I made tea. I sat at the kitchen table with the radio low, the way Derek liked it. Outside, wind pushed dry leaves into slow spirals across my porch.

I pulled out my household ledger and flipped to the last year.

Two thousand for Jeremy’s water heater.

Six hundred for Sheila’s dental work.

Eight hundred for Caitlyn’s school trip.

Twelve thousand for garage repairs that never seemed to get fully fixed.

Every dollar I’d handed over. Every time I’d nodded and said, Of course, because mothers are trained to confuse giving with love.

My phone rang at 5:17.

Jeremy.

I stared at his name until it stopped.

Five minutes later, a text arrived.

Mom, we need to talk. Are you free tonight?

I didn’t reply.

At 7:43, Caitlyn called again, voice low and tense.

“Grandma,” she said, “Dad and Mom are saying you’re confused. They keep saying it, like they’re practicing.”

My pulse slowed, not because I wasn’t upset, but because something in me recognized the tactic.

“They said you should consider a care home,” Caitlyn whispered. “Not to your face. But when they think I can’t hear.”

“Thank you for telling me,” I said softly.

“I don’t think you’re confused,” she said, voice cracking. “I think you’re the only one who sees what’s happening.”

“I see it,” I replied. “And I’m not going to let them scare you.”

After we hung up, I stood at the window and watched streetlights click on one by one. Jeremy and Sheila thought they were clever. They thought they could slide me into silence with paperwork and concern, call it help, call it love.

They forgot who raised Jeremy. They forgot I buried a husband and still got up and paid the bills. They forgot that old does not mean helpless.

I woke early the next morning. At seventy-two, your bones wake you before the sun. I made coffee and pulled out the small red notebook I hadn’t opened in years, the one Derek used to call my rainy day file.

Inside were receipts, old letters, notes I’d saved without knowing why. A sticky note from three years ago that said, Mom, can you sign this quick? City permit, urgent. I’d signed. Of course I had.

A printed form authorizing temporary access to my investment account. A Christmas card from Sheila with an extra envelope tucked inside containing a list titled joint expenses to reimburse Jeremy approved by mom.

My signature at the bottom.

I stared at it, not with shock anymore, but with something worse.

Recognition.

By ten, I was in my car. Beige, boring, dependable. The kind of car an older woman drives when she has nothing to prove and everything to protect.

At the bank, the lobby smelled like carpet cleaner and air conditioning. A young teller smiled at me with professional sweetness.

“I need to speak to a manager,” I said.

Mr. Lee came out a few minutes later, tie patterned with ducks, smile trained in seminars. He guided me into a glass-walled office.

“I’d like a full review of my last twelve months of activity,” I said. “And I want to know what authorizations are active on my accounts.”

His eyes moved across the screen, then paused. He swallowed.

“There are active links,” he said carefully. “One joint authorization on an auto-transfer to an external account in the name of J. Reynolds and S. Reynolds.”

“How much?” I asked.

“It’s been running monthly,” he said. “Fifteen hundred dollars on the third. Categorized as maintenance support.”

“Stop it,” I said.

He blinked. “Excuse me?”

“Cancel it immediately,” I replied. “And I want written confirmation today.”

He hesitated. “It was authorized under a power of attorney on file.”

“That document has been revoked,” I said. “My attorney will send you the new one today.”

Mr. Lee cleared his throat. “Understood.”

I leaned forward. “I also want restrictions. No future changes without in-person verification. No online amendments. No phone amendments.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

He printed the last twelve months of transactions and slid them across the desk. The stack felt heavier than paper should.

Back home, I spread the statements across my kitchen table. Dry cleaning. Caterers. Amazon orders for electronics. A payment to a photography studio I didn’t recognize. A flagged transaction, emergency withdrawal, twenty-five hundred.

I hadn’t made that withdrawal. Jeremy had access then.

I stared out at the bare maple trees swaying in the wind and felt something inside me settle into place, solid and cold.

This wasn’t a misunderstanding.

It was theft.

And I was going to treat it like what it was.

That afternoon, my phone started ringing. Jeremy. Then Sheila. Then Jeremy again. I watched their names flicker on the screen like warnings. Finally, a voicemail arrived.

“Mom, we need to talk. The bank says I’m not authorized anymore. Are you okay? Call me.”

I didn’t.

I made tea. I opened the curtains and let the gray light in, soft and honest. That honesty felt better than their concern ever had.

The next morning, I went to the police station with my documents in a folder. The building smelled like old coffee and linoleum, the kind of place where people sit on plastic chairs trying not to cry. I didn’t cry. I sat with my purse in my lap and my coat buttoned like I was there for jury duty.

Officer Hernandez brought me into a small interview room with thin walls and a buzzing fluorescent light overhead. I handed him copies of the revoked document, the bank statements, and a written summary Michael helped me prepare.

“This isn’t a criminal complaint,” I said, “not yet. But I want it on record.”

He flipped through the papers, eyes scanning. “You’re saying your son attempted to use authority to access your funds,” he said slowly, “and you suspect tampering at a family gathering.”

“I didn’t get sick,” I said. “But someone did. And there is motive tied to incapacity.”

He exhaled. “Do you have evidence?”

“I have a witness,” I said carefully. “And I have a pattern.”

He nodded. “We can file this as a protective record,” he said. “If something escalates, it establishes context.”

“Good,” I replied.

When I left, the sun was already dropping behind the bare trees, turning the sky pale gold. Winter sunsets don’t last long, but they linger just enough to remind you that time moves whether you are ready or not.

That evening, I called Leonard Hayes.

Leonard had been Derek’s friend once, a retired detective with a dry voice and eyes that missed nothing. We’d drifted after Derek died the way people do when grief changes the shape of conversations, but I still had Leonard’s number in an old address book.

He answered on the third ring.

“Marge,” he said. “Still breathing.”

“Still paying attention,” I replied.

He chuckled. “What’s the occasion?”

“I need a favor,” I said. “And I need someone who won’t try to talk me out of it.”

Leonard went quiet for a beat, then his voice steadied. “All right,” he said. “I’m listening.”

I told him about the gravy, the plate switch, Sheila’s illness, the documents, the bank transfers, the way Jeremy and Sheila were already saying the word confused like they were laying railroad tracks in my direction. Leonard didn’t interrupt. When I finished, he said, “I’ve seen this before. The slow bleed dressed up like concern.”

“What do they do next?” I asked.

“They get desperate,” he said. “They try to isolate you. They push for evaluations. Guardianship. They will be careful now because you’re awake.”

“I want backup,” I said. “Not a badge. Not a gun. Just someone who knows what people do when they’re cornered.”

Leonard hesitated, then said, “All right. I’m in.”

The next morning, he showed up with black coffee and a folder tucked under his arm, stepping onto my porch like he belonged there.

“You still take it black?” he asked, handing me the cup.

“I still take it seriously,” I replied.

He set the folder on my kitchen table and started laying out papers. Clippings, typed notes, printouts. Then he pulled out a single sheet and placed it in front of me like it was heavier than the rest.

It was an email.

From Sheila.

Addressed to someone at a local elder care agency.

Subject: Urgent. Need consultation for cognitive evaluation of aging parent.

I read the message twice. Sheila was asking how to initiate a wellness review without my consent, how to begin the process of having me evaluated, labeled, managed.

The room went very quiet. Even the refrigerator hum seemed to soften.

“She’s laying the foundation,” I said, my voice low.

Leonard nodded. “They want the courts involved.”

“They won’t get it,” I replied.

Leonard tapped the paper. “You want me to dig deeper?”

I stared at Sheila’s words, at the careful language she used to make manipulation sound like concern, and something in me hardened into clarity.

“No,” I said. “I want to answer it.”

Leonard blinked. “You want to respond to her?”

“Not in writing,” I said. “In person.”

That afternoon I dressed the way I used to dress for parent-teacher conferences back when Jeremy still needed me to show up. Not fancy, not severe, just clean lines that said I knew where I was and why I was there. A long wool coat. Low heels I could walk in without wobbling. A simple blouse and a small gold necklace Derek gave me on our twentieth anniversary. No perfume. No dramatic lipstick. If they wanted to paint me as confused, I was going to give them a picture they couldn’t smear.

Leonard insisted on following in his own car, not close enough to look threatening, just near enough to be a quiet anchor. He didn’t say much on the drive. He didn’t have to. The kind of men who have seen too many courtrooms know that silence is sometimes the safest weapon.

Jeremy and Sheila’s neighborhood looked like it always did, neat lawns trimmed even in winter, wreath hooks still hanging on doors, mailboxes lined up like obedient soldiers. Their house sat in the middle of it, gray siding, white trim, the kind of place that looked perfect in family photos. I parked at the curb instead of their driveway. I wanted the walk up to the front door to be visible, deliberate, the way you walk into a room when you refuse to be snuck in as an afterthought.

I rang the bell once.

The door opened a crack and Caitlyn’s face appeared, surprised. Her eyes widened, then softened, then flicked behind her as if she was checking whether it was safe to let me in.

“Grandma,” she whispered.

“Hi, honey,” I said gently. “Is your mother home?”

Caitlyn hesitated. “She’s upstairs,” she said. “Dad’s not here.”

“All right,” I replied. “Could you tell her I’m here?”

Caitlyn stepped back and opened the door wider. The house smelled like eucalyptus and new furniture, that staged-clean scent people use when they want life to look controlled. I walked in slowly, closed the door behind me, and stood in the entryway like a guest who refused to apologize for existing.

Caitlyn hurried up the stairs and I heard her knock on a bedroom door. Her voice was low. Then footsteps. Then Sheila appeared at the top of the stairs, her hair smooth, her face arranged, her posture already defensive.

She came down as if she was descending into a negotiation.

“Margaret,” she said, her voice too polite. “This is unexpected.”

“It’s necessary,” I replied.

She stopped a few steps away, arms crossing over her chest. “If you’re here to accuse us again,” she began.

I held up my hand, not aggressive, just firm. “I’m here to be clear,” I said.

Sheila’s eyes narrowed. “About what?”

I reached into my purse and pulled out the printed email Leonard had given me. I didn’t wave it around. I didn’t brandish it. I simply held it out.

Sheila’s eyes dropped to the paper. The color drained from her face in a way no makeup could hide. For a moment her mouth opened but no sound came out, like her brain had to catch up to the fact that her private plan was now in someone else’s hands.

“You went through my email,” she said finally, voice sharp.

“I didn’t have to,” I replied. “You sent it. You typed it. You put it into the world. All I did was see it.”

She grabbed the paper and skimmed it, lips tightening with each line. Her fingers trembled, barely, then she forced them still, as if control could be summoned by willpower.

“This is out of context,” she snapped.

“It’s perfectly in context,” I said calmly. “It’s exactly the context you tried to create.”

She took a step toward me, eyes flashing. “We were worried about you.”

“You were building a case,” I corrected. “A case that starts with whispers and ends with paperwork.”

Sheila’s jaw clenched. “You’re paranoid.”

I let that word hang in the air for a second, because it was the word she wanted to plant, the word she wanted to make sticky.

“Paranoid people don’t revoke power of attorney properly,” I said. “They don’t meet with their attorney. They don’t lock down accounts. They don’t file protective reports. They don’t show up calm and dressed for daylight. Paranoid people spiral. I’m not spiraling.”

Sheila’s nostrils flared. “What do you want?”

“I want you to stop,” I replied. “Stop calling me confused. Stop trying to initiate evaluations. Stop trying to use systems meant to protect older adults as a tool to control one.”

Her eyes flicked to the staircase, where Caitlyn stood halfway up, gripping the banister like she didn’t know whether to run or stay. Sheila followed her gaze and something cold moved across her face, the kind of anger that isn’t loud but is sharp.

“This is between you and us,” Sheila said.

“It became between me and my granddaughter the moment you dragged her into your lies,” I said. I kept my voice even, but inside my chest something tightened, protective. “She is not a chess piece.”

“She’s a child,” Sheila snapped.

“She’s a person,” I corrected. “And she’s been watching you.”

Caitlyn’s eyes filled, but she didn’t look away. That steady gaze again, the one I recognized, the one that belonged to the women in my family who learned early how to survive rooms full of people pretending.

Sheila drew in a breath like she was trying to regain her composure. “Margaret,” she said, lowering her voice, “you can’t just show up in my house and make threats.”

“I’m not making threats,” I replied. “I’m making boundaries.”

She scoffed. “You think you can control this?”

I held her gaze. “I already did.”

Sheila’s face tightened with something like fear. She didn’t want to feel fear. She wanted to be the person who pulled strings. But fear has a way of arriving when control slips.

“I have retained legal counsel,” I continued, calm as a metronome. “All prior authorizations are revoked. The bank has documentation. The police have a record. If you attempt to contact me directly, or through intermediaries, it will be treated as harassment. If you attempt to initiate evaluations without cause, it will be documented and challenged.”

Sheila’s voice went thin. “You think you can just… ruin our family.”

I stared at her. “You already did,” I said quietly. “All I did was notice.”

Her eyes flicked again toward the window, toward the street, as if she suddenly realized what it meant to be seen. In a neighborhood like this, people watch. They pretend they don’t. But they do. They notice which cars come and go. They notice which curtains move. They notice which porch lights stay on too late.

I took a slow breath, then turned slightly toward Caitlyn.

“Sweetheart,” I said softly, “I’m going to leave now. You can call me anytime. Day or night.”

Sheila’s head snapped. “Caitlyn is staying out of this.”

Caitlyn’s voice, small but firm, came down the staircase like a stone dropped into water. “I’m already in it.”

Sheila’s face went rigid. “Excuse me?”

Caitlyn stepped down one more stair, shoulders trembling but her eyes steady. “I heard what you said,” she told her mother. “I heard what you’ve been saying about Grandma.”

Sheila’s mouth opened, then shut again. In that brief moment, I saw the panic she tried to hide. Not panic that she’d hurt someone. Panic that her version of the story was slipping.

I didn’t press the moment. I didn’t need to. It was already cracking on its own.

I nodded at Caitlyn once, a small gesture that said I saw her, I believed her, and then I turned back to Sheila.

“Tell Jeremy,” I said. “From now on, everything goes through my attorney.”

Sheila’s voice trembled with anger. “You’re making a huge mistake.”

“No,” I replied, and my voice was quiet but solid. “I’m correcting one.”

I walked out without waiting for permission. The cold air outside hit my cheeks like a wake-up slap. Leonard’s car was parked down the street, idling, his headlights low. I walked to my own car, hands steady on the keys, and drove away with the kind of calm that isn’t softness, but resolve.

That night the calls began again.

Jeremy, three times.

Then Sheila.

Then Jeremy.

I watched the screen light up, flicker, go dark, like a warning signal someone kept trying to force into my life. I didn’t answer. I let the silence do what it needed to do.

At 9:14 p.m., a voicemail arrived.

“Mom,” Jeremy’s voice said, and the concern in it sounded rehearsed now, like a script. “We’re worried. You’re acting erratic. You showed up at our house and scared Sheila. If you don’t call me back, we might have to take steps to make sure you’re safe.”

Safe. The word used like a leash.

Leonard listened to the message the next morning and shook his head slowly.

“They’re escalating,” he said.

“I know,” I replied.

He sipped his coffee and looked at me over the rim of the cup. “You ready for what comes next?”

I stared at my kitchen table, at the papers stacked neatly in a folder, at the bank printouts, at the revised documents Michael had drafted, at the copy of Sheila’s email that sat on top like a rotten cherry.

“I’ve been ready for years,” I said. “I just didn’t know it.”

Michael met me at his office later that afternoon. He didn’t waste time with comfort. He laid out reality the way lawyers do when they respect you.

“They will likely attempt a welfare check or an adult protective services referral,” he said. “They will frame it as concern. They will claim memory lapses, confusion, paranoia. Their goal is to create an official record that supports their narrative.”

“And my goal is to show the opposite,” I replied.

Michael nodded. “Exactly. So we prepare.”

He had me schedule a cognitive baseline appointment with my primary doctor, not because I believed I needed it, but because documentation matters. He had me gather routine evidence of functioning: utility bills paid on time, records of my driving, my medications listed properly, my calendar kept neatly. In America, dignity can be argued in receipts.

We also finalized the trust structure, moving my primary assets under protection with a neutral co-trustee until Caitlyn turned eighteen. Michael explained every line. I asked questions until my throat went dry. Then I signed with a hand that didn’t shake, because fear had finally stopped driving.

On the drive home, I passed the elementary school where I once picked Jeremy up from after-school programs. I remembered his little backpack bouncing, his hand in mine, the way he used to run to me like I was the whole world. Grief is strange. It doesn’t only arrive when someone dies. Sometimes it arrives when someone becomes someone you no longer recognize.

That weekend, Caitlyn came over with a backpack and a tight expression.

“They’re not talking to each other,” she said, dropping into my kitchen chair like her bones were tired. “Dad slammed a door so hard it rattled the frames.”

I poured her hot chocolate, extra marshmallows the way Derek used to do for Jeremy, and watched her hands wrap around the mug like she was trying to hold herself together.

“They keep saying you’re unstable,” she whispered. “They keep saying it like it’s… like it’s a spell.”

“It’s not a spell,” I said. “It’s a strategy.”

Caitlyn swallowed. “They told me I can’t come here anymore.”

My chest tightened. Not with surprise, but with a deep, old ache. They would use the child as leverage. Of course they would.

“You can always come here,” I told her. “But I don’t want you trapped in the middle.”

“I’m already in the middle,” she said, and her voice cracked. “And I don’t want to be on their side anymore.”

I reached across the table and took her hand. Her fingers were cold.

“Listen to me,” I said softly. “Truth has consequences. Not because truth is wrong, but because lies hate being exposed. If they punish you for telling the truth, that is not a family you owe loyalty to. That is a system you survived.”

Caitlyn’s eyes filled. She blinked hard, like she hated crying. “I don’t want to lose my parents,” she whispered.

“I know,” I said, and my voice went gentle. “But losing them isn’t the same as losing your worth. You don’t become smaller just because they choose darkness.”

She nodded, trembling.

Three days later, the knock came.

It was mid-morning, gray light spilling across the kitchen floor, the radio low, my coffee half-finished. The doorbell rang once, then again, polite but insistent.

Leonard was already in my living room, pretending to read the newspaper while actually listening to the street like a man trained to hear trouble before it speaks.

I walked to the door and looked through the peephole.

Two uniformed officers stood on my porch. One held a folder, the other a tablet. Their faces were neutral, professional, not hostile, but there was an underlying stiffness that told me this wasn’t a casual hello.

I opened the door halfway, chain still latched. Cold air rushed in.

“Mrs. Reynolds?” the taller officer asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Ma’am,” he said, “we’re here regarding a request for a welfare evaluation.”

I didn’t flinch. I didn’t gasp. I didn’t give them drama they could interpret as instability.

“On what grounds?” I asked calmly.

The officer glanced down at his folder. “A family member expressed concerns regarding your ability to manage finances and maintain safety.”

I nodded slowly as if we were discussing weather. “I want my attorney present,” I said.

The officers exchanged a look, then the one with the tablet nodded. “That’s your right,” he said. “We can wait.”

I stepped back, closed the door gently, and locked it. The click sounded clean.

Leonard stood from his chair, eyes sharp. “That was fast,” he said.

“It was inevitable,” I replied, reaching for my phone.

I called Michael first. Then I called Leonard’s number, even though he was in the room, because he insisted it mattered for documentation, for record, for time stamps. He always thought like that.

Michael arrived within forty minutes, coat still on, briefcase in hand, his face calm the way calm looks when it’s earned. He spoke to the officers with respectful firmness, asked for the referral details, asked for the specific claims. He made them explain, line by line, what had been alleged.

Memory lapses. Increasing confusion. Paranoia. Inability to manage finances.

I watched the officer’s mouth form those words and felt something in me settle again, not hurt this time, but clarity. They had truly chosen their story. They had committed to it.

Michael handed the officers copies of my revised documents. The trust paperwork. The revoked power of attorney. The bank restriction letter. A letter from my doctor confirming I’d scheduled a baseline appointment. Evidence of routine functioning.

The officers read quietly, their faces shifting slightly as the narrative in their hands diverged from the narrative they’d been told.

“Mrs. Reynolds,” the taller officer said finally, voice gentler, “we’ll note that you have legal representation and updated documentation. This referral will be forwarded accordingly.”

“Thank you,” I replied.

They left a card on my counter and walked back down my steps, their boots crunching softly on the thin layer of snow.

When the door closed, my house felt warmer. Not because the heat changed, but because I had passed the first test.

Michael turned to me. “They tried to make you flinch,” he said quietly.

“They picked the wrong woman,” I replied.

Leonard let out a slow breath. “They’ll try again,” he said.

“I know,” I replied. “But now there’s a record that they tried.”

That evening, Caitlyn texted me.

They came, didn’t they?

I typed back.

They did. I handled it. I’m still here.

Her reply came almost immediately.

I’m scared.

I stared at the words, then typed slowly, careful.

It’s okay to be scared. Just don’t let fear decide what’s true.

A long pause.

Then her message.

I want to tell you something else. Something I didn’t say before.

My fingers went still over the phone.

I wrote back.

Call me.

When her call came through, her breathing sounded tight, like she’d been holding this in her ribs for days.

“Grandma,” she whispered, “I recorded them.”

The room seemed to sharpen around me. Even the hum of the fridge sounded louder.

“What do you mean?” I asked, keeping my voice calm for her.

“After Thanksgiving,” she said, voice shaking, “I heard them downstairs. They thought I was in the basement. They were arguing. Mom said something like… like it should have been you. And Dad said he didn’t mean for it to be bad, just enough to make you look… confused.”

My throat went tight.

“I didn’t know what to do,” Caitlyn whispered. “I didn’t want to ruin everything. But then they started talking about putting you in a home. And then the police came today. And I realized… they’re not stopping.”

I closed my eyes. For a moment, the grief surged, not a wave, but a heavy, slow pressure. Not grief that Jeremy had become capable of this. Grief that the truth was now undeniable.

“Caitlyn,” I said softly, “you did the right thing.”

“I feel sick,” she whispered. “I feel like I betrayed my parents.”

“You didn’t betray them,” I said gently. “You refused to betray yourself.”

She breathed shakily. “What do I do with the recording?”

“You don’t send it to anyone,” I said. “Not yet. You keep it safe. You bring it to me when you can, quietly. We’ll give it to Michael properly.”

There was a pause, then her voice broke. “Are you going to be okay?”

I opened my eyes and looked at my kitchen, at the small, ordinary details that had become sacred because they proved I still had a life. The dish towel hanging crooked. The bowl of apples on the counter. Derek’s old mug on the shelf.

“I am going to be more than okay,” I told her. “I’m going to be prepared.”

After we hung up, Leonard watched my face like he could read weather in it.

“She’s got something,” he said.

“Yes,” I replied.

Leonard nodded slowly, the way a man nods when he knows the game has shifted. “Then it’s time,” he said.

That night I sat at my kitchen table with the folder of documents in front of me and a blank sheet of paper beside it. I didn’t write a dramatic speech. I didn’t write a letter full of anger. I wrote a timeline, clean and factual, because facts are harder to twist.

Thanksgiving dinner. Jeremy’s insistence. Plate switch. Sheila’s illness. Caitlyn’s observation of the dropper bottle. Discovery of the durable power of attorney. Bank transfer documentation. Revocation. Attempts to label me unstable. Sheila’s email. Welfare evaluation referral.

Line by line, date by date.

Then I folded the paper and placed it in the folder like it belonged there.

I turned off the lights, walked upstairs, and lay in bed listening to the quiet. For the first time in weeks, the quiet didn’t feel like loneliness. It felt like space. Space to plan. Space to breathe.

And somewhere beneath that calm, something else pulsed steadily, like the low roll of distant thunder.

They had started this with a smile and a gravy boat.

Now they were going to learn what happens when a woman stops pretending she doesn’t see.

The next morning, the sky was the color of unwashed glass, and the neighborhood looked too quiet for what was moving underneath it. I made coffee, not because I wanted it, but because routine is a kind of spine. I stood at the sink and watched steam rise from the mug, watched my own reflection in the window, and felt the strange split inside me between the woman who had once believed in family by default and the woman who was now learning that belief is not the same as safety.

Leonard sat at my table with his newspaper open, but his eyes weren’t reading. Every few minutes he glanced toward the street like he was listening with his whole body.

“You want to call her?” he asked.

“I already told her not to message details,” I said. “We do this properly. Quietly.”

“Quiet doesn’t mean slow,” Leonard replied.

“I’m not being slow,” I said, and surprised myself with how steady my voice sounded. “I’m being precise.”

At 10:15, Caitlyn texted me a single sentence: Can I meet you somewhere? Somewhere not here?

I stared at the message for a moment, then typed back: Yes. The diner off Route 9. Booth by the window. Bring nothing obvious.

Leonard raised an eyebrow as I grabbed my coat.

“You want me to come?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “Not yet. If she’s already being watched at home, I don’t want your presence to make it feel like an operation. I want it to feel like a granddaughter meeting her grandmother for pancakes.”

Leonard’s mouth twitched. “Pancakes with evidence,” he said.

“Exactly,” I replied.

The diner was the kind of place that still served coffee in thick white mugs and kept a pie case by the register like a shrine. A faded American flag hung near the window, and a small sign on the wall advertised the Friday fish fry at the VFW. The smell hit me the moment I walked in, butter and bacon and old fry oil, and for a second it transported me back to the years when Derek and I came here after church, laughing over nothing, holding hands like the world couldn’t shift under our feet.

I slid into the booth by the window and kept my hands on the table, visible, calm. A waitress with silver hair and a no-nonsense face poured me coffee without asking, as if she remembered me from another life.

“You want your usual?” she asked.

“Not today,” I said. “Just coffee, thank you.”

She nodded, as if she understood more than I said, and walked away.

Caitlyn arrived ten minutes later, slipping in like she was trying not to be seen. She wore a hoodie pulled tight around her face and carried her backpack high on her shoulders. When she spotted me, her posture loosened slightly, but the fear didn’t leave her eyes.

She slid into the booth across from me and kept her hands under the table like she was holding something there.

“Hi, Grandma,” she whispered.

“Hi, honey,” I replied. “Look at me.”

She lifted her eyes.

“You’re not in trouble,” I said softly. “You’re not bad. You’re not disloyal for telling the truth. You understand that?”

Her mouth trembled. “I keep thinking I ruined everything.”

“No,” I said. “They ruined it. You just stopped letting it stay hidden.”

The waitress returned and asked Caitlyn what she wanted. Caitlyn ordered hot chocolate, no whipped cream, voice barely audible. When the waitress walked away again, Caitlyn leaned forward, elbows tight against her ribs.

“I have it,” she said.

“Tell me how,” I replied. “No details you’re not comfortable with. Just enough so we can handle it safely.”

Caitlyn swallowed. “My phone,” she whispered. “I used the voice memo app. I didn’t plan it. I was shaking. I just… pressed record and put it in my pocket.”

“Good,” I said, and kept my tone gentle. “That means it’s time-stamped.”

She nodded quickly, as if she hadn’t realized that mattered.

“I didn’t send it to anyone,” she said. “I didn’t even play it again. I was scared I’d… I don’t know, mess it up.”

“You did exactly right,” I told her. “Do you have your phone on you?”

She hesitated, then nodded.

I leaned forward slightly. “I’m not going to take it,” I said. “I’m not going to touch it. Not here. Not until Michael tells us the best way. But I want to hear enough to know what we’re dealing with.”

Caitlyn’s eyes filled. “It’s bad,” she whispered.

“Then we handle it like adults,” I said. “And we protect you while we do.”

The waitress set down Caitlyn’s hot chocolate, the steam curling up between us like a veil. Caitlyn wrapped her hands around the mug, and for a moment she looked like she was eight again, small and bracing against the world.

“Are they watching me?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “But I’m going to act like they might be. That’s not paranoia. That’s caution.”

Caitlyn nodded, then reached into her backpack and pulled out a small envelope. Not a manila folder. Not anything dramatic. Just an ordinary envelope, slightly crumpled from being gripped too hard.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“My backup,” she whispered. “I… I copied the audio file onto a little drive. A flash drive. I put it in here.”

My stomach tightened and softened at the same time. Fear, yes, but also pride. Not because she was building a case. Because she was thinking like a person who wanted to survive.

“Did you label it?” I asked.

She shook her head. “No.”

“Good,” I said. “And you didn’t write what it is anywhere?”

“No,” she whispered.

I nodded slowly. “All right. Here’s what we’re going to do. You’re going to keep that with you for now. You’re not going to hand it to me in the diner. You’re going to finish your hot chocolate. You’re going to go home like you just had breakfast with your grandmother. And later, you and I will meet Michael together. In his office. He will tell us how to transfer it properly.”

Caitlyn stared at me. “What if they take my phone?”

“Then they won’t find what they don’t know exists,” I replied. “And even if they try, you will not be alone. You have me. You have Michael. You have Leonard. You have options.”

Her eyes finally spilled over. Tears rolled down her cheeks silently, the kind of tears teenagers hate because they feel like betrayal of their own strength.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

“For what?” I asked.

“For not saying something sooner,” she said. “For letting it get this far.”

I reached across the table and touched her hand lightly, just enough to ground her. “Honey,” I said, “it didn’t get this far because of you. It got this far because two adults chose to do wrong and assumed no one would stop them. The fact that you did stop them is the only reason we’re sitting here with a chance.”

Caitlyn wiped her cheeks with her sleeve and nodded, breathing through the storm.

“Do you want pancakes?” I asked, not because pancakes mattered, but because normalcy is sometimes a life raft.

She let out a shaky laugh. “No,” she said. “But I want you to eat something.”

“I will,” I promised.

We sat a moment longer, sipping warm drinks, and outside the window, cars passed on the road like the world had no idea what we were carrying inside this booth. When Caitlyn stood to leave, she hugged me tight, her arms strong, her shoulders trembling.

“I love you,” she whispered.

“I love you too,” I replied, and felt the truth of it like a steady weight.

When she walked out, I watched her go until the door swung shut behind her. Only then did I pick up my phone and call Michael.

He answered on the first ring, as if he’d been waiting.

“Mrs. Reynolds,” he said.

“I have something,” I replied. “A recording. My granddaughter made it. It implicates them.”

There was a pause, and then his voice sharpened into professional focus. “Do not email it,” he said. “Do not text it. Bring the device in person. We’ll make a copy on our secure system and document chain of custody.”

“Understood,” I said.

“Bring Caitlyn,” he added. “We’ll protect her, too.”

By the time I drove home, the daylight had shifted, a thin sun breaking through clouds like a reluctant witness. Leonard was waiting by my kitchen window, arms crossed, eyes on the street.

“You got it?” he asked.

“We have it,” I corrected. “But we’re doing it right.”

Leonard nodded, satisfied. “Good,” he said. “Because once you put fire on paper, people start running.”

Michael scheduled us for that afternoon. Caitlyn arrived straight from school, still in her hoodie, cheeks red from cold and nerves. Michael greeted her with a calm warmth that didn’t feel like pity. He offered her water, showed her a chair, and spoke to her like she was a person whose voice mattered.

“I want you to know you did something brave,” he told her. “But brave doesn’t mean alone. From here forward, we handle this in a way that keeps you protected.”

Caitlyn nodded, gripping her backpack straps until her knuckles went pale.

Michael had her take out her phone and the flash drive. He didn’t touch them at first. He took photos of the devices where they sat on his desk, documented the time, and then had his assistant bring in a small evidence envelope like the ones you see on crime shows, except this one smelled faintly of office paper and ink.

“We’re not making drama,” Michael said quietly. “We’re making record.”

He copied the audio file onto a secure drive while Caitlyn watched. When it was done, he sealed the flash drive in the envelope and wrote a date across the seal. Then he sealed a copy, too, and placed both into his safe.

Caitlyn sat very still, her face pale.

“I want to hear it,” I said.

Michael studied me. “Are you sure?” he asked.

“I’m past sure,” I replied.

Michael played the first minute only. He stopped it before it could become a wound we couldn’t close. But it was enough.

Sheila’s voice, sharp and low, saying words that made my blood turn cold without needing any vivid description. Jeremy’s voice, defensive, anxious, trying to justify, trying to make it sound like it wasn’t what it was. The phrases weren’t clean. They weren’t hypothetical. They carried intent, and they carried the kind of casual cruelty that only comes from people who have decided another person’s life is an obstacle.

Michael paused the recording and the room went quiet. Caitlyn’s breathing sounded loud. My own heartbeat sounded steady, which surprised me. I thought I would feel like I was falling. Instead I felt like I was standing on rock after months of mud.

Michael looked at Caitlyn. “You did the right thing,” he said again, softer now. “You gave us leverage and protection.”

Caitlyn’s eyes were wet, but she nodded.

Then Michael looked at me. “This shifts the situation,” he said. “It can move from civil protections to criminal investigation, depending on what law enforcement determines and what medical documentation exists.”

“I want it on record,” I said.

“It will be,” he replied. “But we do it in a controlled way.”

He made calls while we sat there. Not to Jeremy. Not to Sheila. To the correct channels. To an investigator he trusted. To an advocate familiar with elder exploitation cases. He spoke in careful language, not dramatic, not emotional. He described pattern, intent, and risk. He requested a formal appointment, not a rushed complaint, because rushed things give people room to say you were frantic.

When he hung up, he leaned back and exhaled.

“Here’s what happens next,” he said. “We maintain your calm profile. We continue medical baseline documentation. We keep your finances locked. We limit contact. And we prepare for retaliation.”

“Retaliation like what?” Caitlyn asked, voice small.

Michael’s gaze softened. “They may try to isolate you from your grandmother,” he told her. “They may attempt to punish you emotionally. They may threaten legal action to scare you. But they cannot erase what you captured.”

Caitlyn swallowed. “My mom said she might take my phone.”

Michael nodded. “Then we document that, too,” he said. “And if it becomes a custody issue or a coercion issue, we involve the right authorities.”

Caitlyn looked at me, fear still in her eyes, but something new there too. A tiny spark of relief. A sense that adults were finally standing in front of her instead of behind her.

When we left Michael’s office, the courthouse square outside looked the same as always, American flags on poles, brick buildings, a bronze statue of a soldier nobody remembered by name. Ordinary. But I felt different moving through it. I felt like a person walking with her name fully attached to her body.

Caitlyn walked beside me to my car. She paused before opening the door.

“What if they hate me forever?” she asked quietly.

I looked at her, really looked. “Then that’s their choice,” I said. “Not your fault. You don’t sacrifice your soul to keep someone else comfortable.”

Her chin trembled. “I don’t want to be the reason they fall apart.”

“You’re not the reason,” I replied. “You’re the reason someone survives.”

That night, the letter arrived.

It was in a pale blue envelope, the kind people use for baby showers and wedding invitations, soft paper, elegant cursive. My name on the front. No return address.

I opened it with my letter opener, slicing neatly across the top. Inside was a single page, typed, no greeting, no signature, just a wall of measured words. It accused me of defamation. It claimed I had threatened them. It warned of legal action if I continued to “harass” them.

I read it twice, then set it on the table.

Leonard sat across from me, watching my face.

“They’re baiting you,” he said.

“I know,” I replied.

He tapped the paper with one finger. “They want you to respond sloppy. They want you loud.”

“They won’t get it,” I said.

Michael advised a response, short and clean, sent certified. Not a fight. Not a debate. A boundary with teeth.

I typed it myself on my old laptop, the one Derek used to call my stubborn machine because it refused to die.

To whom it may concern, I have retained legal representation. All prior authorizations granted to Jeremy and Sheila Reynolds have been formally revoked and documented. Any attempt to contact me directly or through intermediaries will be treated as harassment and referred to appropriate authorities. Your intimidation is noted. It changes nothing. Margaret Reynolds.

No emotion. No insults. Just record.

The next morning I mailed it certified, standing in line at the post office beneath a flag and a faded poster reminding people to report suspicious packages. When the clerk stamped the receipt and slid it across the counter, I felt a strange calm. A paper trail is not justice, but it is a foundation for it.

Three days passed in silence.

On the fourth day, a car I didn’t recognize pulled into my driveway.

Black. New. Windows tinted.

It sat there for nearly ten minutes, engine idling. No one got out. No one rang my bell. It was presence without action, a message delivered through stillness.

Leonard watched from the living room window, eyes narrowed.

“That’s pressure,” he said.

“It’s theater,” I replied.

He looked at me. “You want to call it in?”

“No,” I said. “Not yet. Let them waste their energy trying to scare a woman who’s already done being afraid.”

The car eventually drove away. But the message lingered in the quiet it left behind.

That afternoon, Caitlyn came over, pale and tight with worry. She sat on my couch like she didn’t know where to put her hands.

“They told me I’m not allowed to see you anymore,” she whispered.

My chest tightened, not with surprise, but with grief. It hurt differently when the cruelty touched her.

“Did they say why?” I asked, though I already knew.

“They said you’re not stable,” she replied. “They said you’re manipulating me. They said I’m being dramatic.”

I leaned forward and held her hands. “Listen to me,” I said softly. “You are not crazy. You are not dramatic for reacting to wrongdoing. They are trying to rewrite reality because reality is dangerous for them.”

Caitlyn’s eyes filled. “What do I do?” she whispered.

“You keep your head down at home,” I told her. “You don’t argue. You don’t try to convince them. You stay safe. And you keep records. Quietly. Dates. Comments. Anything that feels like pressure.”

She nodded, trembling.

Leonard stepped into the room and kept his voice gentle. “If they try to keep you from leaving the house, if they take your phone, you call your grandmother from a school office,” he said. “Or you talk to a counselor. You’re not trapped.”

Caitlyn looked at him like he was a stranger and a lifeline at the same time. She nodded again.

When she left, hugging me hard at the door, I watched her walk to the sidewalk and disappear down the street like a piece of my own heart being carried away.

That night I sat at my kitchen table and unfolded the pale blue letter again, then placed it beside the certified mail receipt and the police station card and the bank confirmation and my trust documents. A small stack of paper that represented something bigger than paper.

I thought about all the times I’d signed something quickly because Jeremy asked. All the times I’d said yes because mothers are trained to believe no is cruelty. I thought about the way he smiled too hard over gravy, as if his own mother was a problem to solve.

And then I thought about Caitlyn, her hands shaking around a mug of hot chocolate, her courage arriving in a voice memo.

By midnight, I had made another decision. Not a dramatic one. A practical one. The kind of decision people like Jeremy and Sheila never expected from me, because they had spent years assuming I would always choose peace over truth.

I called Michael and left a message. Just one sentence.

I want to proceed with a formal complaint under oath, and I want to discuss a no-contact letter.

Then I set my phone down and went to bed.

I didn’t sleep much. But the few hours I did sleep were heavier, deeper, like my body finally understood that denial was over and preparedness had begun.

The next morning, the call came from Michael’s office.

“We have an appointment,” his assistant said. “County investigator. Tomorrow at eight.”

Eight in the morning. Early enough to feel official. Early enough that people couldn’t accuse me of drinking wine at lunch and getting emotional. Early enough to look like exactly what it was: a woman taking back her own life while the rest of the town was still stirring creamer into coffee.

I hung up and stood in my kitchen, looking around at the ordinary world that had become my battlefield. The dish towel. The calendar. The bowl of apples. The quiet.

Leonard came in from the living room and watched me for a moment.

“You okay?” he asked.

“I’m steady,” I said.

He nodded slowly. “That’s the most dangerous thing you can be to people like them,” he said.

I smiled faintly, and it wasn’t the kind of smile you wear for family photos. It was the kind you feel when you stop waiting for someone else to save you.

Tomorrow, I would walk into an office and put the truth on paper where it could not be laughed off as paranoia. I would do it without shouting. Without tears. Without giving them the scene they wanted.

And somewhere in the quiet, I could almost feel Jeremy and Sheila realizing what they had underestimated.

Not my anger.

My clarity.

News

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

Twenty-seven years ago, an entire kindergarten class suddenly vanished without a trace, leaving families with endless questions. Decades later, one mother noticed something unusual in an old photograph and followed that detail to a box of long-forgotten files. What she found wasn’t meant to accuse anyone, but it quietly brought the story back into focus, connected names and timelines, and explained why everything had been set aside for so many years.

Twenty-seven years ago, an entire kindergarten class vanished without a trace and left a small Georgia town with a hole…

Five players vanished right after a match, and the case stayed at a dead end for 20 years. No one’s account ever fully lined up, every lead broke apart, and their last known moments slowly turned into small town rumor. Then a hiker deep in the woods picked up a tiny, timeworn clue that clearly did not belong there. One detail matched an old case file exactly, and that was enough to put the story back in the spotlight and launch a renewed search for answers.

The gym at Jefferson High sounded like a living thing that night, all heat and echoes, all rubber soles and…

A group of friends out shopping suddenly stop in their tracks when they spot a mannequin in a display that looks eerily like a model who has been out of contact for months. At first, they tell themselves it has to be a coincidence, but the tiny details start stacking up fast. The beauty mark, the smile, even a familiar scar. A chill moves through the group. One of them reaches out to test the material and then freezes at an unsettling sensation. Instead of causing a scene, they step back, call 911, and ask officers to come right away. What happens next turns what seemed like a harmless display into a moment none of them will ever forget.

Quincy Williams and his friends walked into an upscale fashion boutique on Main Street in Demopoulos, Alabama, the kind of…

For 25 years, a museum kept an item in its archives labeled a “medical specimen.” Then one day, a mother happened to see it and stopped cold, recognizing a familiar detail and believing it could be connected to the son she had lost contact with long ago. From that moment, everything began to unfold into a long story of overlooked records, lingering unanswered questions, and a determined search for the answers her family had been waiting for for years.

Atlanta, Georgia. Diana Mitchell stood in the bodies exhibition at the Georgia World Congress Center and felt something she had…

The day I signed the divorce papers, I thought that would be the most painful moment, until he walked out and immediately filed for a new marriage, as if I had never existed. I quietly ended my working arrangement with my sister-in-law to keep my dignity intact. But that night, 77 calls came flooding in, and my in-laws’ line about “55 billion dollars a year” kept repeating like a warning. That’s when I realized this was no longer private.

The day I signed the divorce papers, I told myself that had to be the lowest point. I had braced…

End of content

No more pages to load