“Don’t cry, ma’am,” he whispered, so low the words almost stayed inside his own mouth.

The fighting had ended the way it often did near the end of a war, not with a clean final shot, but with a thinning of sound until the world seemed to realize, all at once, it was still standing. A few distant pops carried across the broken town like echoes that hadn’t gotten the message yet. Then there was only wind moving through shattered window frames and the small, restless noises of people trying to remember what a normal breath felt like.

In the street, brick dust clung to everything. It coated helmets, sleeves, eyelashes, the edges of torn posters still stapled to a wall that no longer had a building behind it. Smoke hung low, not thick anymore, but stubborn, like it refused to admit defeat. The sky had the washed-out color of late spring after rain, pale and almost polite, as if the sun didn’t want to look too closely at what had been done.

A line of German prisoners waited near a half-collapsed curb under American guard.

There were men with hollow eyes and boys whose faces had not finished becoming men. There were a few women too, fewer than the men, which somehow made them stand out more, not because anyone wanted them to, but because war taught people to expect enemies in certain shapes. The women wore uniforms that looked like they belonged to someone else now, fabric hanging too loose, collars worn thin, belts pulled tight past the holes they were meant to use.

One of the women sat down.

She did it slowly, as if even sitting might be misunderstood. Her knees bent with care. Her boots scraped the stone. When she lowered herself onto the broken edge of the curb, she kept her hands visible in her lap like she was still being watched by a world that would punish the wrong movement. Her coat sagged at the shoulders and the wind found every gap in the seams.

Then her face crumpled.

Not dramatically. Not loudly.

Quietly, like her body had saved the tears for a moment when there was no longer a reason to hold them back. They ran down her cheeks in clean lines through the dust, and she tried to stop them with the side of her hand, wiping too roughly, as if tears were a mistake she needed to erase before someone saw.

Most people looked away.

Some looked away out of habit, because war trained you to keep moving. Some looked away because you didn’t know what looking would demand. Some looked away because tenderness felt dangerous, and the end of a war did not immediately erase the rules people used to survive it.

The American GI who noticed her had been awake long enough that time no longer felt reliable.

His name was Daniel Foster. Most men called him Foster. His sergeant sometimes called him “kid,” even though Foster didn’t feel like a kid in any way that mattered. His uniform was dusty in the seams, his helmet sat low, and his eyes looked rimmed red from smoke and grit rather than emotion. He stood with the tired efficiency of someone who had repeated the same motions until they became muscle memory.

Foster was supposed to be watching the line.

He was supposed to keep the prisoners where they were until the transport came. He was supposed to maintain distance, follow procedure, remember the side he was on. That was what training told him, and training was the thing you leaned on when your mind threatened to slip.

But the woman’s quiet crying cut through routine the way a wrong note cuts through music.

Something in him paused.

Not long enough to be obvious. Just long enough to choose.

He stepped closer.

He didn’t stride. He didn’t announce himself. He moved with the quiet caution of someone who had learned that sudden gestures could be misread. He stopped a few feet away and looked down at her. She kept her head lowered, her shoulders shaking in small, controlled tremors like she was trying to keep the sound inside her throat.

Foster hesitated.

He felt eyes on him, not many, but enough. He could sense men behind him shifting, boots scuffing, someone muttering under their breath. He could sense his sergeant’s attention like heat.

He knelt anyway.

His knee touched damp stone. The fabric of his trousers darkened where the moisture seeped in. It was such a simple movement it almost looked accidental, like he’d dropped something and was reaching for it. He did not tower over her. He did not crowd her. He just lowered himself to her level so his presence wouldn’t feel like another threat.

He didn’t speak right away.

Words could make things worse. Words could turn a private collapse into a public moment, and public moments were dangerous in wartime. But the way her breath hitched, the way she pressed her knuckles to her lips to keep the sound inside, made his chest tighten.

In broken German he barely remembered from training, he said softly, “Don’t cry, Frau.”

The accent was wrong. The phrase came out clipped. But the meaning didn’t need polish.

She froze.

Her shoulders went still the way an animal goes still when it senses danger. She didn’t look up yet. She simply stopped crying for a heartbeat, as if the interruption shocked her body into silence.

Foster’s hand lifted before he could think.

It wasn’t a grand intention. It wasn’t a plan. It was instinct, the same instinct that made someone steady a child stepping off a curb. His fingers, rough and dirty, brushed her cheek and wiped away a tear that had reached the edge of her jaw.

The touch lasted barely a second.

It was small.

It was completely unauthorized.

The moment his fingertips met her skin, a flash of fear ran through him, not fear of her, but fear of being seen doing this. War was built on boundaries. Boundaries simplified impossible moral calculations. Boundaries told you who deserved empathy and who did not.

In that instant, he crossed a boundary without moving his boots.

She looked up.

Her eyes were pale and tired, rimmed red. They were the eyes of someone who had been hungry too long and afraid too long. The image Foster had been trained to expect, enemy, threat, fanatic, did not fit the woman sitting there with tears on her face and hands that trembled like they couldn’t remember how to be safe.

Her gaze flicked to his uniform, to the rifle slung at his shoulder, to the American flag sewn onto his sleeve. Confusion widened her eyes. Not anger. Not gratitude. Confusion, as if her mind could not find a place to file this kind of moment.

Kindness from an enemy wasn’t something she knew how to catalog anymore.

Foster held still.

He didn’t smile. He didn’t apologize. He didn’t try to explain. He simply stayed present long enough for her breathing to slow, for the shaking in her shoulders to lessen. He let the moment exist without forcing it to become anything else.

Around them the street kept moving.

A jeep coughed somewhere nearby. A soldier laughed too loudly, trying to push sound into the emptiness. Someone called an order. The machinery of surrender and relocation continued, indifferent to a single quiet exchange.

After a few seconds, Foster rose smoothly, careful not to startle her, and stepped back into line as quietly as he had come.

The moment ended in silence.

No cameras. No reporters. No one writing a note about a tear wiped away in a ruined street. Reports counted bodies and supplies. They listed distances and dates. They did not make room for mercy that complicated the story people needed.

Still, a few people noticed.

A medic standing near a blown-out doorway saw Foster kneel. The medic’s hands were stained with iodine and his eyes carried too much of other people’s pain. He didn’t react. He just watched, brow furrowing like he was trying to fit the scene into a category he didn’t have.

An interpreter saw it too, an American corporal with German parents, drafted young enough to still have a trace of an accent. He tightened his jaw and glanced toward the sergeant, checking whether this would become trouble.

The sergeant noticed the bend of Foster’s body, the way he leaned in.

For half a second his face hardened, then shifted into something like resignation. Men did strange things at the end of a war. He had seen worse. He had seen better. He had learned to file some moments away without comment because comment could make them ugly.

The sergeant said nothing.

The medic said nothing.

The interpreter said nothing.

The war moved on.

A truck arrived later with a canvas back and benches inside. Prisoners were counted and directed forward. Orders were barked in English, translated into German with clipped efficiency. The German woman stood when she was told. She kept her eyes on the ground. Her face was blank again, controlled, as if the tears had never happened.

But as she stepped up into the truck, she hesitated for half a second, her hand tightening on the edge of the canvas.

Foster saw it.

He couldn’t explain why he noticed. It was the same sensitivity that had made him kneel, a radar for the moment someone might break. He felt an urge to say something, to offer a word that could hold, but he had no words left that felt safe.

The interpreter leaned close to the woman and murmured in German, gentle but firm. It sounded like instructions, not comfort. She nodded once and climbed in.

Foster watched her disappear behind the canvas flap.

He told himself that was the end of it.

He told himself he would forget.

He was wrong.

That night, Foster’s unit bivouacked in a half-collapsed barn on the outskirts of town. The roof leaked in two places. Straw was damp. Men smoked cigarettes that tasted like paper and relief. Someone passed around a can of peaches from a ration crate, and the sweetness hit Foster’s tongue like a memory he didn’t want.

He lay on his back with his helmet under his head and stared at dark beams overhead. Men around him murmured, laughed, coughed, shifted. The barn smelled of wet hay, sweat, and old animals. Outside, the night was cold and quiet in a way that still didn’t feel real.

Foster closed his eyes and saw the woman’s face.

Not as an enemy.

Not as a symbol.

As a person.

He told himself he shouldn’t have touched her.

He told himself he could get in trouble if someone wanted to make trouble.

He told himself he’d done it without thinking, and that was the problem.

Then, under all those thoughts, another truth moved like a slow current.

It had felt wrong not to.

Across the barn, the medic sat on an upturned crate cleaning his hands with water that didn’t quite remove the smell of the day. His name was Thomas Reilly. Before the war he’d been a medical student in Boston, the kind of young man who believed healing was always clean and gratitude was always waiting at the end.

The army taught him better.

It taught him that bodies failed in ugly ways and that doing your best didn’t always mean doing enough. It also taught him that sometimes the most difficult wounds were the ones you couldn’t bandage.

Reilly watched Foster from the corner of his eye.

Not judgment.

Curiosity.

He had seen men become harder, crueler, meaner. He had seen men become numb in a way that frightened him more than anger. Foster’s face held a different kind of change, like a man who had been reminded of something he did not know how to name.

Reilly waited until most of the barn had gone quiet.

Then he cleared his throat softly.

Foster opened his eyes.

Reilly’s voice was low, meant for one person. “You all right?”

Foster’s first instinct was to shrug it off, to say yes, to make it nothing. That was the currency of the army. Nothing bothered you. Nothing got under your skin.

But Reilly’s tone held no mockery and no edge.

“I’m fine,” Foster said.

Reilly nodded like he believed him and didn’t. “You didn’t do anything wrong, if that’s what you’re thinking.”

Foster stared at the beams again. “Did you see it?”

“I did,” Reilly said.

Foster swallowed. The barn felt tighter suddenly, the air heavier. “I shouldn’t have done that.”

Reilly’s gaze stayed steady. “Maybe. Maybe not.”

“That’s not a real answer,” Foster muttered.

Reilly’s mouth twitched, not quite a smile. “Welcome to the end of a war.”

Foster let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding. “She was crying.”

“I know,” Reilly said.

“She looked,” Foster searched for the right words and hated how none of them fit, “she looked like my sister when she was little. When she fell off her bike and tried not to cry because she didn’t want our dad to see.”

Reilly’s face softened. “Yeah.”

Foster’s voice dropped. “I didn’t even think. I just did it.”

Reilly leaned back against the barn wall. The wood was rough. “You saw a person. That’s all.”

“That’s not how it’s supposed to work,” Foster said, and the bitterness surprised him.

Reilly’s eyes flicked toward the sleeping men, the piles of gear, the helmets, the rifles. “No,” he agreed. “It isn’t.”

Foster’s throat tightened. “What if she did terrible things?”

Reilly didn’t flinch from the question. He didn’t rush to reassure or preach. He gave Foster something closer to truth.

“Maybe she did,” Reilly said. “Maybe she didn’t. Either way, she was crying in the street. You wiped a tear. You didn’t rewrite the war.”

Foster’s jaw worked. “It felt like I did something I wasn’t allowed to do.”

“You did,” Reilly said quietly.

Foster turned his head. “Then why aren’t you chewing me out?”

Reilly looked down at his hands. “Because if we make rules that forbid mercy entirely,” he said, “then what are we fighting for?”

Foster didn’t have an answer.

Silence stretched, not hostile, just heavy.

Reilly’s voice dropped even lower. “Just don’t talk about it here.”

Foster stared at him. “You’re telling me to hide it.”

“I’m telling you the truth about where we are,” Reilly said. “Men are tired. They’re angry. They’re clinging to a simple story because simple stories keep them steady. If you give them a story that makes them feel complicated, they won’t thank you.”

Foster’s eyes closed. “So I keep it to myself.”

Reilly nodded. “You keep it to yourself.”

Then Reilly added, almost as if he was speaking to the dark rather than to Foster, “It’ll follow you anyway. Quiet things always do.”

He wasn’t wrong.

The woman’s name, Foster would learn decades later, was Anneliese Krüger.

In 1945, she did not feel like a name to him. She felt like a body. A body that had been told to move and stop and move again. A body that had learned the trick of staying upright when the world wanted to fold you. A body that had learned to look at uniforms without seeing the faces inside them because faces invited grief.

Anneliese had grown up outside Leipzig in a town where church bells once kept time for everyone’s lives. Her father ran a modest shop that sold paper, pens, and small things people needed until they didn’t. Her mother kept the books and kept the peace. Anneliese liked languages because words felt like doors, and doors felt like a promise that the world was larger than what you could see from your street.

Then war came and doors became walls.

By the time she wore a uniform, she was no longer a girl. She was not a zealot. She was not a symbol. She was a woman who watched choices shrink until every option felt like a trap. She did what she was told because not doing it would have cost her the little control she still had.

She learned quickly that despair was dangerous. Despair made you careless. Carelessness got you noticed. Not being noticed was the closest thing to safety.

So she kept her face still. She followed instructions. She learned to conserve energy the way other people conserved money. She learned not to hope because hope made disappointment sharper.

In the final weeks, everything blurred into confusion. Orders shifted. People disappeared. Roads filled with bodies moving in every direction, as if the world had become a shaken box and everyone inside it slid toward the corners.

Anneliese spent so long bracing for death that when death didn’t come, her body didn’t know what to do with the extra air.

That afternoon, in the ruined street, when she sat down, the crying surprised her. She hadn’t decided to cry. She hadn’t chosen it. It simply happened, as if tears had been waiting behind a locked door and the lock finally failed.

She tried to stop.

Then she heard a voice.

Not sharp. Not ordering. Not mocking.

“Don’t cry, Frau.”

The touch on her cheek shocked her more than any shout would have. Her mind screamed warning, enemy, danger, trick, because she had learned to expect cruelty from uniforms in any language.

But it wasn’t a trick.

It was just a hand.

Warm, rough, real.

The moment frightened her precisely because it did not fit the rules of the world she had been surviving. For a few seconds, she was not a prisoner or an enemy or a number. She was a woman crying, and someone refused to treat her tears like a crime.

Then it ended because war allowed nothing to linger.

In the truck, pressed between bodies and canvas, she stared at her hands in her lap as if they might explain what had happened. She did not speak of it to anyone. She tucked it away like a smuggled piece of bread.

In the camp that followed, she learned new routines.

Camp life was not what she had feared, not exactly. It was structured. It was hungry. It was cold. It was full of waiting. Guards were not always cruel, but they were always in control, and control itself was exhausting to live under.

There were other women. Some older, their hair turned gray too early. Some younger, eyes too old for their faces. Some spoke too loudly, trying to fight the silence. Some had stopped speaking entirely, as if words had become a debt they could no longer pay.

Anneliese did what she had always done.

She became invisible.

She became useful.

She learned which guard might trade a cigarette for a bit of translation, which nurse might slip an extra spoonful into a bowl if you didn’t make her feel watched. She learned that dignity could be preserved in small ways, by washing your face when water was scarce, by straightening your clothing even when it was torn, by saying thank you to people who had forgotten how to hear it.

At night, when the barracks were quiet, she sometimes pressed her fingertips to her cheek where the American’s hand had been.

Not longing.

Proof.

It had happened.

The war had not managed to kill all mercy.

She kept that knowledge private. In a camp, shared softness could become liability. People could mock it, resent it, demand it. Anneliese kept it sealed inside herself like a seed.

Years passed. The camp ended. The war ended. The world declared itself new.

But the moment stayed.

Foster went home in 1946 with a duffel bag and dog tags and a body that looked intact and a mind that did not.

The train rides and ships were full of men trying to act like the war was a dream that would fade once they smelled home again. They joked. They played cards. They talked about food and women and baseball and the shape of their old beds.

Foster stared out windows at landscapes that looked like they belonged to someone else.

He expected relief.

He felt numbness instead, and beneath it, an ache he couldn’t name.

Back in Kansas, the town looked smaller than he remembered. The main street was the same. The diner smelled like grease and coffee. His mother cried when she saw him. His father gripped his shoulder hard, the way men did when they were trying not to show too much.

His sister, Ruth, ran into him so fast she nearly knocked him over. She had grown. Her hair was longer. Her face older. She hugged him like she was trying to prove he was real.

Foster held her and felt his throat burn.

He told himself it was joy.

It was grief too, but he didn’t say that.

People asked questions the way people ask questions when they want a clean story.

Did you see fighting?

Were you scared?

Did you kill anyone?

Do you hate them?

Foster learned quickly that most people didn’t actually want answers. They wanted confirmation. They wanted the war to fit into a shape that made them feel safe, a shape that justified every loss, every ration, every headline.

He gave them what they could handle.

He said yes.

He said sometimes.

He said it was hard.

He said he was glad to be home.

He did not tell them about the woman crying on a curb.

He did not tell them about the moment his hand moved on instinct.

He did not tell them how kindness had felt risky, like stepping onto ice you weren’t sure would hold.

He tried to bury it.

Quiet things don’t stay buried. They surface at inconvenient times, not to punish you, but to insist you remember who you were.

The first time his mother cried at the kitchen table because she burned the bread, Foster froze. The sound of her sniffing, the way she turned her face away as if ashamed, pulled him back into that ruined street so sharply he almost dropped the plate in his hand.

He stepped closer before he could think.

He touched his mother’s shoulder.

She startled and looked up, confused.

Foster sat down without a word. He didn’t try to fix it. He didn’t try to turn it into a joke. He simply stayed until her breathing evened out and her embarrassment loosened.

It wasn’t the same as Europe. Nothing could be the same. But the thread was there, thin and undeniable.

Presence mattered.

He married later, a local woman named Elaine who liked books and had a laugh that came easily. Elaine didn’t push him to talk about the war, but she watched him with the quiet attentiveness of someone who understood that silence often held heavy things.

Sometimes, when Foster came home from work and sat too still at the table, Elaine would pour him coffee and sit across from him without speaking. She didn’t fill the air with questions. She didn’t demand stories. She gave him room.

Foster loved her for that in a way he couldn’t explain.

Years passed. Children came. A son and a daughter. Holidays. Birthdays. Work at the grain elevator, then later at a farm equipment dealership where men talked about harvests like they were prayers. The world moved forward and the war receded into something people referenced in speeches and movies.

Still, the memory followed him.

Not as a dramatic haunting with shadows in corners, but as a small pressure that changed the way he moved through life. He became a man who couldn’t tolerate cruelty dressed up as humor. He became a man who left the room when someone joked about suffering as if pain could be reduced to a punchline. He became a man who watched his children’s faces when they cried and felt something tighten in his throat every time he saw them try to hide tears out of shame.

He didn’t teach them war stories.

He taught them, without naming it, that no one should be punished for being human.

Anneliese returned to Germany to a place that did not feel like a country so much as a question.

Her town had been damaged but not erased. The church still stood, though the bell sounded different, thinner, like it had lost some metal in the air. Her father was gone. Her mother had aged in a way that made Anneliese’s stomach twist because it meant time had been spent without her, time she could not reclaim.

They did not cry when they saw each other.

They held each other stiffly at first, then with desperate strength.

That evening, her mother made thin soup with what she could find. They ate slowly, as if chewing too quickly might wake a nightmare. Her mother asked careful questions that circled the edges of what Anneliese did not want to say.

Anneliese answered what she could.

She did not talk about the American.

Not because she felt loyalty, not because she felt shame. She simply did not know where to place him in her life. The moment was too strange, too bright. It did not belong in the same room as the rest of her story.

She found work translating for a local office. Languages still felt like doors. She opened them carefully. The world rebuilt itself in uneven steps. People learned to stand in lines again. People learned to smile again, though smiles took time to look real.

She married a man who did not ask too much about the past. They had children. They built a life because building was the only way to keep the rubble from winning.

The moment stayed.

Sometimes, when her daughter cried as a small child, Anneliese wiped the tears gently and felt a strange ache in her chest, as if she was repeating an act she once received and never understood. Sometimes, when her son fell asleep after fever, Anneliese sat beside the bed and stayed, remembering that presence could hold fear even when it couldn’t change the future.

She never told her husband the story. He would have asked what it meant. She did not have an answer.

It meant nothing and everything.

It meant the war had not managed to kill all mercy.

It meant mercy could cross lines people insisted were uncrossable.

It meant an enemy had seen her crying and had not used it.

That was enough.

In the early 1980s, when the world began to reopen old cabinets and pull out old files, a young archivist in Leipzig approached Anneliese for an interview. The project was meant to document women’s experiences in the final months of the war, not propaganda, not politics, just testimony before testimony disappeared.

Anneliese almost refused.

Her children were grown. She had learned the skill of quiet living. She had spent decades trying not to poke the past. She didn’t want to invite it back into her kitchen.

But the archivist’s eyes were earnest. She reminded Anneliese, faintly, of herself before the war, a young woman who believed words could change what had happened if you arranged them correctly.

So Anneliese agreed.

They sat in a small office with weak winter light. A recorder whirred softly on the table. The archivist asked questions with a careful kindness that made it harder to hide behind simple answers.

What did you see.

What did you fear.

What did you lose.

Anneliese answered slowly. She spoke of hunger, of uncertainty, of the way rumors could control a room. She spoke of walking past buildings that had once been homes, now open to the sky. She spoke of the end, and how the end did not feel like an end, only a shift.

Then the archivist asked, almost gently, “Did anyone show you kindness?”

Anneliese blinked, startled by the question.

Kindness was not usually what people wanted from war stories. People wanted bitterness or heroism. They wanted clean moral lines they could draw with a ruler.

Anneliese hesitated.

The moment returned as sharply as if she were back on that curb again, dust on her cheeks, breath catching in her throat. She heard the American’s broken German, soft and imperfect.

Don’t cry, Frau.

She felt the touch.

Her throat tightened.

“Once,” she said quietly.

The archivist leaned forward slightly. “Can you tell me?”

Anneliese looked down at her hands.

“Yes,” she said.

And for the first time in nearly forty years, she spoke the story out loud.

She did not make it grand. She did not turn the soldier into a saint. She described it as it was, a man kneeling in a ruined street, a soft voice, a hand that wiped a tear, then a return to routine as if nothing had happened.

When she finished, the archivist’s eyes were bright, not with excitement, but with something quieter.

“That stayed with you,” the archivist said.

Anneliese nodded once. “Yes.”

The archivist asked, “Did it change what you believed?”

Anneliese could have given an answer that sounded wise. She could have said it made her forgive. She could have said it redeemed something.

She didn’t.

“It reminded me,” she said, choosing each word slowly, “that I was still human when I had begun to forget.”

The recorder whirred. The office was quiet.

The archivist asked, “Do you remember his name?”

Anneliese shook her head. “No.”

“Do you remember his face?”

Anneliese hesitated. “Not clearly. I remember his eyes. I remember he looked tired. I remember he did not look at me like I was a problem.”

When Anneliese left the office, she felt hollow, as if she had removed a small stone from inside her chest and now had to adjust to the emptiness. That night she did not tell anyone she had done it. But she slept, and for the first time in years she dreamed of the ruined street and woke without panic.

The historian who found Anneliese’s interview years later was not German.

He was American. His name was Peter Caldwell, raised in Missouri, educated in the East, the kind of man who believed history was not just dates but lived experience. He grew up with a grandfather who never spoke about the war and a father who spoke about it in jokes that never reached his eyes.

Caldwell spent years chasing fragments.

A medic’s letter in a box of papers no one had opened in decades.

A roster with a name and a unit and no hint of the person inside the uniform.

A transcript from Leipzig that included a story too quiet to fit the headlines.

He did not find the whole thing at once.

He assembled it like someone rebuilding a broken plate, piece by piece, careful not to cut himself on the edges.

When he read Anneliese’s words, he sat back in his chair and stared at his office wall for a long time.

A tear wiped away.

A line crossed without permission.

Not forgiveness. Not absolution.

Recognition.

Caldwell’s first instinct was to write it quickly, to catch the emotion before it cooled. But he had learned that stories like this couldn’t be rushed. If you rushed them, you turned them into something they weren’t.

So he went looking for the other side of the moment.

The medic’s letter led him to Thomas Reilly.

Reilly was old by then, retired, hands less steady, eyes still sharp. He had built a career in medicine, raised a family, created a life that looked ordinary from the outside. He had also built a private cabinet of memories he rarely opened.

When Caldwell called, Reilly listened in silence.

Then he said, very quietly, “Yes. I saw it.”

Caldwell felt his pulse jump. “Do you remember the soldier’s name?”

Reilly hesitated. The pause was not forgetfulness. It was caution, like he was weighing whether the past deserved to be disturbed.

Finally he said, “Daniel Foster.”

Caldwell wrote it down as if the ink could anchor something.

He asked, “Do you know where he is now?”

Reilly didn’t, not for sure. But he had instincts, and he had learned over decades how to find people who didn’t want to be found. He made calls. He checked old directories. He followed thin lines of paperwork like tracks in snow.

He found Foster in Kansas.

Reilly wrote him first.

Because the story belonged to the man who lived it, not to the researcher who discovered it.

The letter arrived on a warm afternoon in a plain envelope with an unfamiliar return address.

Elaine brought the mail in and set it on the kitchen table the way she always did, neat and orderly, as if order in small things could keep life steady. Foster glanced at the stack, sorting bills from ads without thinking, until he saw the handwriting.

His fingers paused.

He stared at the name.

Thomas Reilly.

Foster felt a pressure in his chest so sharp he had to sit down.

Elaine looked at him. “What is it?”

Foster swallowed. “It’s someone from the war,” he said.

Elaine didn’t rush him. She pulled out the chair across from him and sat down, hands folded, waiting. She had waited through forty years of his silences. She could wait through another.

Foster opened the envelope carefully, as if paper could break.

He read the first line and felt the barn again, damp straw, smoke, the weight of night.

Reilly’s words were plain. No drama. No apology for the intrusion. Just truth.

Foster read slowly.

Reilly wrote about the ruined street, about the woman crying, about Foster kneeling. He wrote about how he had kept it to himself because he had told Foster to keep it to himself. He wrote that a historian had contacted him with a transcript from Germany, a woman’s testimony, a moment that had survived in words.

Reilly wrote, simply, that the woman lived.

Reilly wrote that her name was Anneliese Krüger.

Reilly wrote that the historian wanted to speak with Foster, not to praise him, not to accuse him, but to understand what the moment meant, if it meant anything at all.

Foster lowered the paper and stared at the table.

Elaine watched his face.

Finally she asked, softly, “She lived?”

Foster’s throat worked. He nodded once.

He did not cry. He did not make a sound. But something in him loosened, something he had carried without realizing it still had weight.

Elaine reached across the table and laid her hand over his.

Foster stared at their hands together, the way Elaine’s fingers rested on his like it was the most natural thing in the world.

He said, so quietly it was almost a whisper, “I never knew.”

Elaine squeezed gently. “Now you do.”

The letter sat on the table between them like a door that had opened to a room they hadn’t visited in forty years.

Foster looked at the paper again. He saw his own name in Reilly’s handwriting and felt something like disbelief. He had lived his life as a man who tried not to be noticed. He had done his work, paid his bills, raised his children, fixed what could be fixed, kept quiet about what couldn’t.

He did not want to become a story.

But he also knew that refusing to answer might feel like another kind of turning away.

Elaine read the letter after him. She held it with care, eyes moving slowly over the lines. When she finished, she looked up.

“You can say no,” she told him.

Foster stared at the window, at sunlight on the yard, at a world that looked safe. “I know,” he said.

Elaine’s voice stayed gentle. “You can also say yes and keep it honest. You don’t have to let anyone turn it into something it wasn’t.”

Foster’s jaw tightened. He felt old anger flare, not at anyone in the room, but at the way people grabbed at stories like tools. He did not want to be made into a lesson someone could use to feel good about themselves. He did not want anyone to use that moment to pretend the war was simple.

“I didn’t do it to be good,” he said, and the roughness in his voice surprised him.

Elaine nodded. “I know.”

Foster swallowed. “I didn’t do it to forgive her.”

Elaine nodded again. “I know.”

Foster’s eyes met hers. “I did it because she was crying.”

Elaine’s gaze didn’t waver. “That’s enough.”

Foster looked back down at the letter.

He imagined the ruined street again.

He imagined the woman’s face.

He imagined her living a life after that, a life he had never pictured because he had never allowed himself to.

He said, quietly, “Tell him he can come.”

Elaine didn’t smile like she’d won. She didn’t act relieved. She just squeezed his hand once and let go, as if she was giving the decision back to him, where it belonged.

When Peter Caldwell arrived a week later, he didn’t come like a man hunting a headline.

He came like someone entering a church.

He stood on Foster’s porch with a notebook in his hand and hesitation on his face, and for a moment, Foster saw the outline of a young soldier in him, the same uneasy respect for something you didn’t fully understand.

Foster opened the door.

Caldwell cleared his throat. “Mr. Foster?”

Foster didn’t correct him. He didn’t invite formality either. He just nodded once.

Caldwell’s eyes flicked past Foster into the house, as if he expected to see the war sitting there in the living room.

Elaine appeared behind Foster, calm, steady. She gave Caldwell a small nod that felt like permission and warning at the same time.

Caldwell swallowed. “Thank you for agreeing to speak with me.”

Foster stepped aside.

Caldwell entered, and the past stepped in with him, not loud, not scandalous, but steady as paperwork and memory and the kind of quiet sacrifice that didn’t ask to be understood.

They sat at the kitchen table, the same table where bills were paid and birthdays were planned, the same table where ordinary life happened.

Elaine poured coffee without asking first. She offered Caldwell a mug. Caldwell accepted with both hands like the warmth mattered.

Foster watched him carefully.

Caldwell opened his notebook but didn’t write right away.

He said, softly, “I don’t want to turn this into something it wasn’t.”

Foster’s eyes narrowed slightly. “Good,” he said.

Caldwell nodded once, as if he expected that response. He hesitated, then asked, “Do you remember the town?”

Foster stared at the coffee in his mug. He could smell smoke again, hear wind through broken glass.

“I remember rubble,” he said. “I remember the street. I remember I was tired.”

Caldwell didn’t press. He asked, “Do you remember her?”

Foster’s mouth tightened.

“I remember tears,” he said.

Caldwell’s pen moved then, but slowly, careful.

Foster lifted his gaze. “If you’re here to make me a hero,” he said, “you’ve got the wrong man.”

Caldwell shook his head quickly. “I’m not.”

Foster’s voice stayed flat. “If you’re here to make her innocent, you’ve got the wrong story.”

Caldwell’s face didn’t change, but his eyes sharpened with understanding. “I’m not doing that either.”

Foster let the silence stretch, testing him, the way he had learned to test people. Caldwell didn’t fill it.

Finally, Caldwell said, “I think what matters is that it happened at all.”

Foster’s jaw worked. “Why does it matter?”

Caldwell’s breath caught slightly. He looked at Elaine, then back at Foster. “Because everyone likes wars to be clean on paper,” he said quietly. “And they never are. And because people still believe mercy has to be permissioned. That if you offer it to the wrong person, it becomes betrayal. Your moment doesn’t erase anything. It just refuses dehumanization for one second.”

Foster stared at him.

Elaine remained still, watching both men the way you watch a bridge being built plank by plank.

Foster didn’t answer right away.

Then he said, quietly, “It wasn’t brave. It was… it was nothing.”

Caldwell’s voice stayed gentle. “It was something to her.”

Foster’s throat tightened.

He looked away toward the window, toward his yard, toward a world that had given him years of ordinary safety.

He said, almost as if he was speaking to himself, “That’s what bothers me.”

Caldwell’s brows lifted slightly. “What?”

Foster swallowed. “That it might have mattered,” he said. “That a second might matter. That’s a lot of weight for a second.”

Caldwell didn’t argue. He didn’t try to lighten it.

He simply nodded.

And in that kitchen, with coffee cooling on the table, the story began to stretch, not into drama, but into the kind of truth that took time to hold.

Foster spoke slowly. He described the street, the dust, the end-of-war quiet that didn’t feel like peace. He described the line of prisoners. He described the woman sitting down as if her knees didn’t trust the world. He described her crying without sound.

He described kneeling, not because he had decided to be kind, but because his body moved before his mind could stop it.

He described the fear that came after, the fear of being seen doing something human.

Caldwell listened without interrupting.

Elaine listened too, and Foster realized with a strange ache that she had lived beside these words for forty years without hearing them. She had known pieces. She had seen shadows. But this was the first time the story sat fully in their kitchen, visible and real.

When Foster finished, he sat back.

His hands trembled slightly around the mug.

Elaine’s hand moved to his wrist, steadying without making a show of it.

Caldwell’s voice was quiet. “Do you want to know what she said about it?”

Foster’s eyes lifted sharply.

Elaine’s fingers tightened.

Foster’s mouth opened, then closed. He didn’t like the feeling of wanting. Wanting made you vulnerable. Wanting made you dependent on an answer you couldn’t control.

Still, the question hung there.

Do you want to know.

Foster stared at the table for a long time.

Then he said, almost inaudible, “Yes.”

Caldwell flipped a page carefully, as if paper could bruise.

He read, not dramatically, just plainly, the words from the transcript.

“It reminded me I was still human when I had begun to forget.”

Foster’s chest tightened.

He swallowed hard and nodded once, as if he was acknowledging a fact he had always known but never admitted.

Caldwell closed the notebook gently. “She doesn’t remember your name,” he said. “She never knew it.”

Foster’s mouth twitched, not quite a smile. “Good,” he said, and the relief in the word surprised him.

Caldwell hesitated. “She remembers your eyes,” he added.

Foster looked down at his hands.

Elaine’s thumb brushed his wrist in a small, steady motion.

Caldwell took a breath. “She’s still alive,” he said softly. “She’s in her seventies now. She agreed to be contacted.”

Foster’s head snapped up.

Caldwell quickly added, “Only if you want. No pressure. She didn’t ask for this. I asked. She said she’d be willing to exchange letters if it helps… if it brings closure, I guess.”

Closure.

Foster hated the word. It sounded like a neat ending, like a door clicking shut.

War didn’t close neatly.

Life didn’t either.

Still, the thought of a letter, paper traveling across an ocean, words arriving in his hands from a woman whose tears he had wiped in a ruined street, made something in him go quiet.

He looked at Elaine.

Elaine met his eyes steadily.

“You don’t have to,” she mouthed, without sound.

Foster nodded slightly.

Then he turned back to Caldwell.

“What would I even say?” Foster asked, and his voice held a rough honesty that made him sound younger than his years.

Caldwell’s expression softened. “Maybe nothing big,” he said. “Maybe you just tell her you remember. Maybe you tell her you’re glad she lived.”

Foster swallowed.

He stared at the window again. Sunlight on the yard. Birds. A world that had forgotten how fragile safety could be.

He said, quietly, “Bring me paper.”

Elaine stood without a word and went to the drawer. She returned with a clean sheet and a pen, placing them in front of him like she was offering him something he had avoided for decades.

Foster held the pen and didn’t move.

His hand hovered over the paper.

He could write a thousand things and none of them would feel right. He could write apologies he didn’t owe. He could write gratitude that didn’t fit. He could write sentences that sounded like a movie.

He didn’t want any of that.

He wanted the truth.

He bent his head and began to write slowly, the pen scratching softly in the quiet kitchen.

He wrote without flourish.

He wrote without heroism.

He wrote like a man finally letting a small, quiet moment take up the space it had always deserved.

He wrote that he remembered the street.

He wrote that he remembered she was tired and crying.

He wrote that he did not know her name then, and he was sorry for that, not as guilt, but as recognition of how war stripped identities down to uniforms.

He wrote that he was glad she lived.

He wrote one line that felt like it came from somewhere deeper than his thoughts.

“I hope the world has been kinder to you than that day was.”

When he finished, his hand shook slightly.

Elaine laid her palm over the paper for a second, not reading, just grounding it, as if she was helping anchor the words to the table.

Caldwell accepted the letter like it was fragile.

He promised he would send it.

Foster didn’t thank him. He didn’t need to. The act of writing had been the thing.

After Caldwell left, the house felt too quiet.

Elaine sat back down across from Foster. She watched him the way she had watched him for forty years, steady and patient and unafraid of silence.

Foster stared at the empty space where the paper had been.

“I didn’t think about her after,” he said suddenly, and the confession made his voice crack.

Elaine didn’t flinch. “Yes, you did,” she said softly. “You just didn’t call it that.”

Foster’s throat tightened.

Elaine leaned forward slightly. “You carried it,” she said. “You carried it the way you carry things you can’t put down.”

Foster’s eyes burned. He blinked hard, angry at himself for the emotion, then tired of the anger too.

He whispered, “What if someone says I shouldn’t have done it?”

Elaine’s voice stayed calm. “Let them,” she said. “They weren’t there.”

Foster swallowed.

He nodded once.

Outside, the day continued, ordinary and bright.

Inside the kitchen, something shifted, not into peace exactly, but into honesty. And honesty, Foster realized, was sometimes the closest thing to peace a person could earn.

Weeks passed.

A letter arrived from Germany in a plain envelope with careful handwriting. Elaine set it on the table like she was setting down something sacred. Foster stared at it for a long time before touching it.

His fingers were steady when he finally opened it.

The paper inside was thin. The ink was neat. The English was careful, slightly formal, as if each sentence had been measured before being allowed onto the page.

Anneliese wrote that she did not know if she should write at all. She wrote that she did not want to disturb his life. She wrote that when the historian asked, she hesitated for weeks, because she did not want the past to climb into her home again.

Then she wrote that she remembered.

Not his name.

Not his face clearly.

But the feeling of being seen as a person when she had begun to believe she was nothing but a number.

She wrote that she had carried that second with her for decades, not as romance, not as a secret to treasure, but as a proof that the world was not entirely broken.

She wrote that she never told her children the story because she did not want them to build their understanding of the war around an enemy’s kindness. She wanted them to understand responsibility and consequence. She wanted them to understand history without turning it into a fairy tale.

Then she wrote that she was old now, and old age had a way of making certain truths less frightening.

She wrote that she was glad he had lived too.

At the end of the letter, she wrote a line that made Foster’s breath catch.

“I did not deserve mercy because I wore a uniform, but I needed it because I was human. Thank you for reminding me I was still human.”

Foster lowered the paper.

His hands trembled.

Elaine reached across the table and held his wrist gently, steadying without making a show of it.

Foster stared at the letter as if it had altered the air in the room.

He said, quietly, “She says she didn’t deserve it.”

Elaine’s voice was soft. “You didn’t give it because she deserved it,” she said. “You gave it because you were still you.”

Foster swallowed.

He blinked hard.

Then, for the first time in decades, he let himself cry.

Not loudly.

Not theatrically.

Quietly, the way a man cries when he is finally tired of being strong.

Elaine did not speak. She moved her chair around the table and sat beside him, her shoulder touching his. She didn’t pat him. She didn’t tell him it was okay. She simply stayed there, sharing the space, letting the moment be what it was.

Outside, the world went on.

Inside, a war that had lived quietly inside a man for forty years loosened its grip by a fraction.

Foster wrote back.

He wrote that he had not thought of her as a symbol. He wrote that he had not been trying to make a statement. He wrote that he did not know what she had done or not done, and he did not pretend his mercy erased history.

He wrote that he was sorry the world had asked so much of them both.

He wrote that he wished he could go back and say more than he had. Then he crossed out the sentence because it felt dishonest. Saying more might have broken the moment. Saying more might have made it about him.

So he wrote the simplest truth.

“I stayed human because I had to live with myself after.”

Months of letters followed.

They were not love letters.

They were not confessions.

They were two people circling a moment with care, trying to understand what it meant without turning it into something it wasn’t. They wrote about families, about small towns, about the way certain sounds still startled them. Foster wrote about Kansas wheat fields and how the wind there sometimes sounded like Europe. Anneliese wrote about her garden and how she learned to find comfort in growing things that did not ask questions.

They wrote about guilt carefully.

They wrote about responsibility without flinching.

They wrote about mercy as if it was a tool that could be used wrong and still be necessary.

Caldwell published his article eventually, and it caused exactly the kind of reaction Foster had predicted.

Some people praised him and made him uncomfortable.

Some people criticized him and made him angry.

Some people tried to use the story as evidence for arguments Foster didn’t want to be part of.

Foster stopped reading the letters to the editor.

Elaine stopped him gently when she saw his jaw tighten.

“You don’t owe strangers your peace,” she told him.

Foster listened.

He kept writing to Anneliese.

In the last letter she sent, her handwriting had grown less steady. The English was still careful, but the words carried a tired tenderness that made Foster’s chest ache.

She wrote that she did not have many years left. She wrote that she was not afraid of dying as much as she had once been. She wrote that she was afraid of leaving words unsaid.

Then she wrote something that did not sound like history or morality or argument.

It sounded like a simple human truth.

“When you touched my cheek,” she wrote, “I understood the war was ending because someone had chosen not to be cruel when he could have been. That is how I knew morning was possible.”

Foster read the line three times.

He folded the letter carefully.

He put it in the drawer with the others.

He sat at his kitchen table and stared at his hands, hands that had built a life, hands that had wiped a tear in a ruined street, hands that now held paper like it mattered.

Elaine came into the kitchen and found him there.

She didn’t ask what he was thinking.

She poured him coffee.

She sat across from him.

She stayed.

And Foster realized, with a strange, quiet clarity, that the story was never about a rule broken or an enemy comforted. It was about what a person chooses to do when no one is watching closely enough to reward or punish.

It was about the shape of humanity in the ruins, when every badge and expectation insisted humanity should be withheld.

It was about the uneasy truth that mercy does not erase responsibility, but it can preserve a soul long enough to face responsibility without turning to stone.

It was about a second that mattered.

Not because it fixed anything.

Because it refused to let the world become entirely unrecognizable.

In the end, Foster did not become a hero in the loud way people imagine.

He became something quieter.

A man who had once knelt in the dust, wiped away a tear, and then carried that small piece of another person’s survival story for the rest of his life, not as a medal, not as an excuse, but as a reminder that even in a world built on lines, a person could still choose to see another person.

And if that could happen in war, the question that followed was not comfortable.

It was necessary.

What would we have to become, in ordinary life, to make kindness feel less forbidden?

News

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

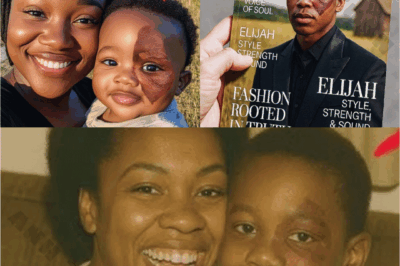

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load