For decades after World War II, a comfortable explanation hardened into tradition across German mess halls, veterans’ clubs, and the private pages of memoirs that tried to make defeat feel logical. The Allies, they said, had won with radar that saw farther, factories that built faster, and resources that never seemed to end. The Atlantic had become a net of aircraft. Convoys moved under an umbrella of steel and radio waves. The U-boat arm, brilliant but outmatched, had been crushed by technology and arithmetic.

It was a story that let professionals keep their posture. It let commanders keep their pride.

Almost no one in that world, not publicly and rarely even in private, put the blame on the one thing they trusted most.

Their own words.

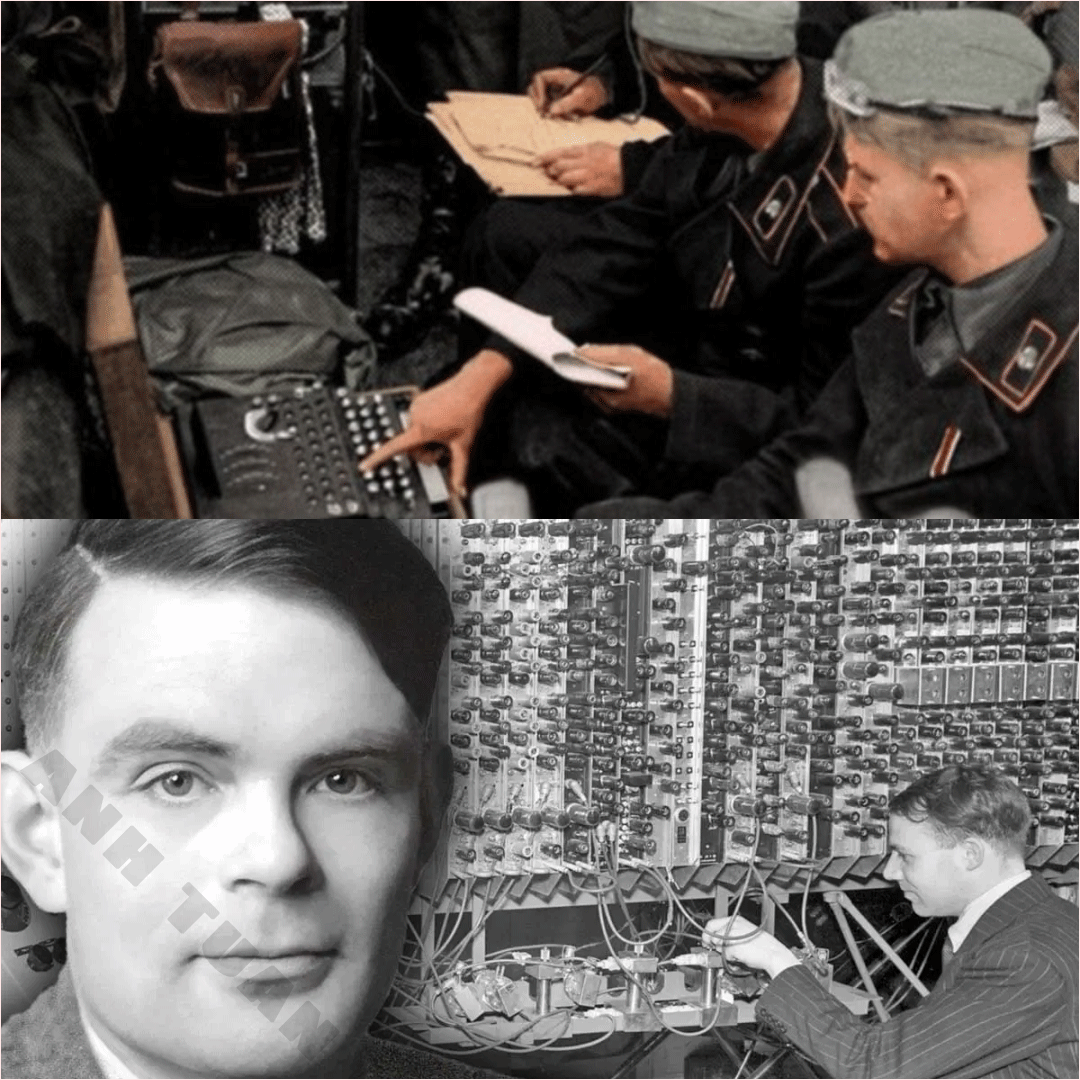

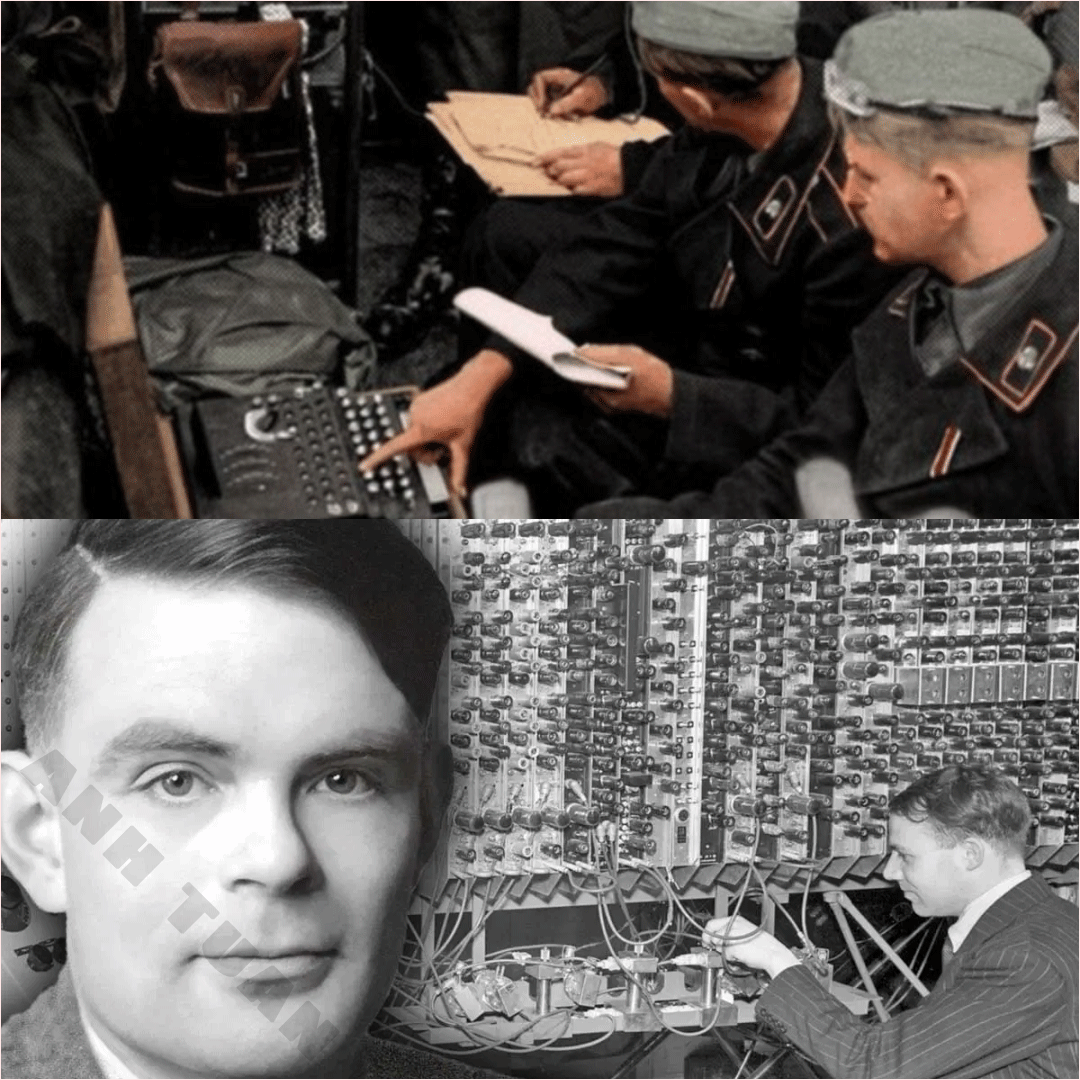

In truth, the decisive advantage had lived behind hedgerows and blackout curtains, inside a British estate that looked, from the road, like a place meant for garden parties and quiet weekends. Bletchley Park did not announce itself as a battlefield. It looked too ordinary to be dangerous. Yet inside its huts, in rooms that smelled of damp wool and cigarette smoke, the war was being read, line by line, as if the enemy’s thoughts were arriving by courier.

That secret remained sealed long after 1945. Not because it was small, but because it was too large to safely tell. When wars end, nations do not stop needing what wars create. Intelligence services do not dismantle their most valuable habits just because the shooting stops. The machinery of silence stayed in place, maintained by laws, by fear, by loyalty, and by the quiet pride of people who had done something impossible and been ordered to pretend it never happened.

Then, in 1974, the secret slipped out through the softest crack imaginable.

A book.

It was late June when copies reached West Germany, stacked like any other new release in bookstores and kiosks. The cover did not glow. The paper did not smell of danger. The title sounded like the kind of phrase publishers love and governments dread: The Ultra Secret. In London, the author’s name moved through official corridors like a dropped glass. In Washington, in beige offices where fluorescent lights made every face look tired, the title showed up in clipped memos and quiet phone calls. Everyone who had been trained to keep the story buried recognized the sound of the earth shifting.

In Darmstadt, West Germany, an aide carried the book into a modest room and placed it on Admiral Karl Dönitz’s desk.

Dönitz was eighty-three, old enough that his face looked carved by weather. The man who had once directed wolf packs across the North Atlantic now lived among ordinary objects: a plain lamp, a worn chair, quiet walls. There was no ceremonial grandeur here, no flags, no staff maps, no aides rushing in and out with urgent updates. Just paper and silence.

He opened the book to a marked page.

The aide sat to one side with the English text, ready to translate carefully into German, as if caution could soften meaning. Dönitz’s hands, veined and still strong enough to grip, held the volume by its edges. His eyes moved steadily across the page. When they stopped, it was not because the sentence was difficult, but because it was impossible.

From May 1940 onward, we read the German naval, army, and air force traffic almost as quickly as the Germans themselves.

For a moment, the room seemed to lose oxygen. Dönitz did not speak. He did not blink. It was as if blinking might concede something. Thirty years of explanations, polished and repeated until they felt like truth, rearranged themselves inside him like furniture in a house struck by an earthquake.

For three decades after the war’s end, he had told the story the way defeated commanders often do, carefully and convincingly, choosing causes that left his decisions intact. Allied radar. Allied aircraft. American shipyards. The sheer density of patrols. He had treated the destruction of his submarine force as the inevitable result of an enemy who simply had more.

The truth in front of him was far more devastating. It suggested that every order he had transmitted, every tactical adjustment, every desperate innovation, had been read by British intelligence, often before his own commanders finished decoding it. It suggested that the war he believed he had fought had been, in part, a performance staged for an opponent who knew the script.

He could almost see the Atlantic again, cold and enormous, swallowing steel and breath. He could see boats leaving Lorient and Saint-Nazaire, sliding into gray water like knives. He could picture the men inside them, cramped and sweating, trusting him and trusting the machine.

Trust the procedure. Trust the keys. Trust the mathematics.

He would write a letter days later, hastily composed, defensive in tone, claiming he had always suspected something like this. It was a sentence that sounded like a man trying to stitch his dignity back together in public. Those who had known him during the war knew that claim did not match the record. His war diary, his postwar memoirs, his testimony at Nuremberg had all shown the same posture: absolute faith, repeated until it became doctrine.

The Enigma cannot be broken.

That certainty had not been a casual opinion. It had been the pillar holding up his entire command system. His greatest innovation, centralized radio control of wolf pack tactics, depended on secrecy being real. Without it, his system did not merely fail. It betrayed.

When the aide kept translating, the words continued arriving like blows. Seven hundred eighty-three submarines lost. Roughly thirty thousand men dead beneath the Atlantic. A casualty rate so high that even enemy admirals spoke of it with a kind of grim respect. If the cipher had been compromised, then the deaths were not only the price of war. They were also the price of believing too hard in something that should have been questioned.

For years, German officers had worshiped the number. Enigma’s theoretical complexity sounded like a cosmic shield. Depending on the variant and assumptions, the configuration space could be described in astronomical terms, a quantity so large it made skepticism feel childish. It allowed men in uniform to tell themselves that certain fears were irrational.

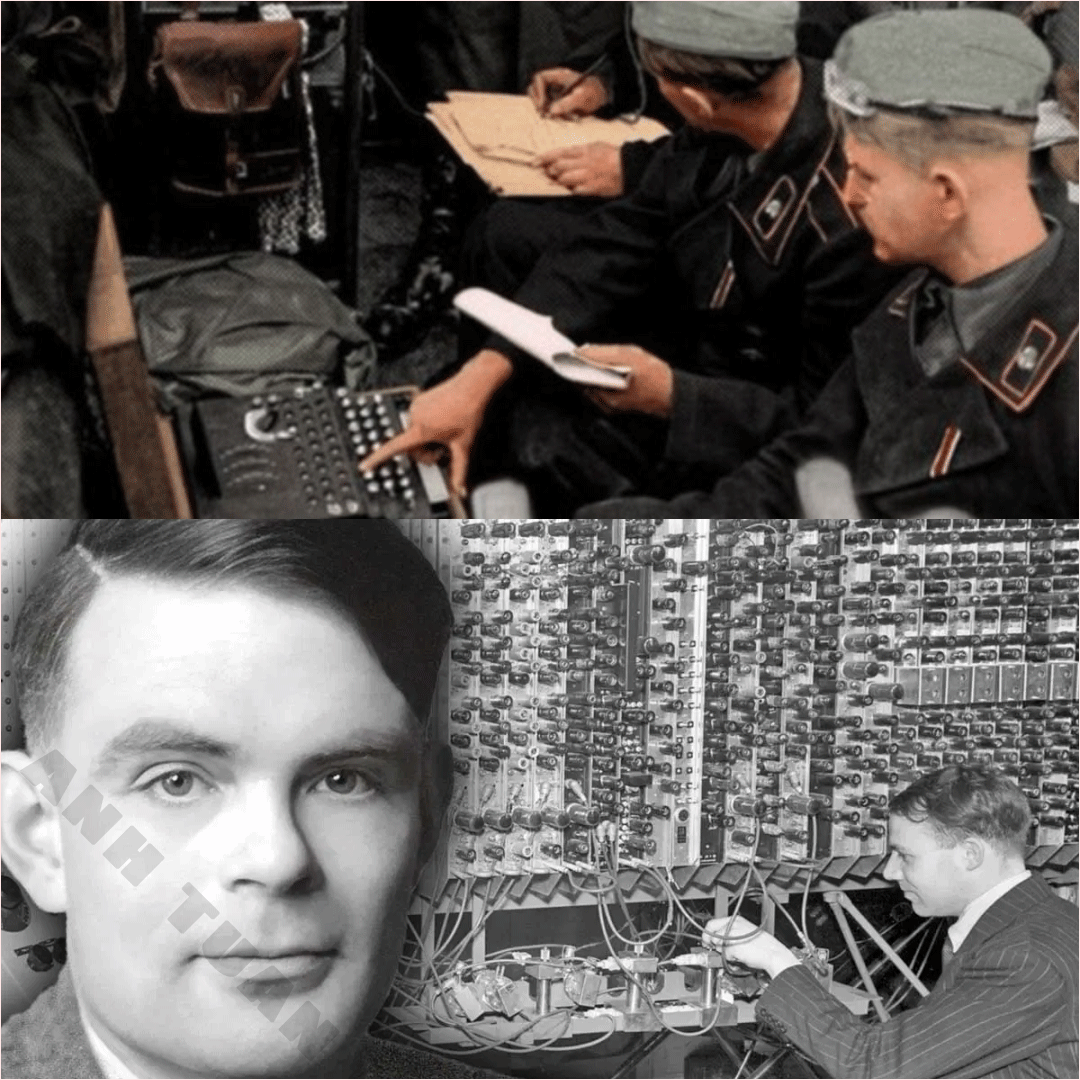

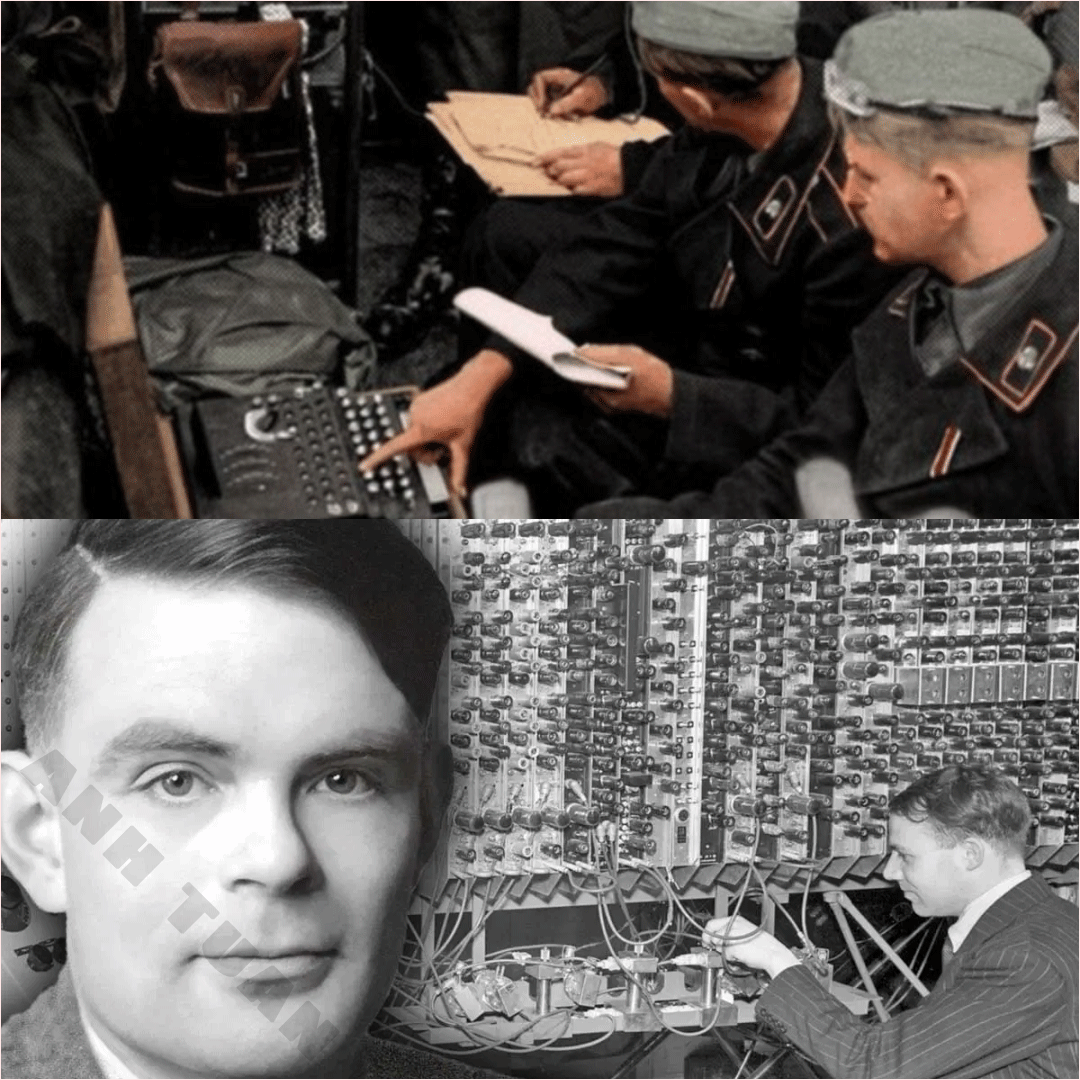

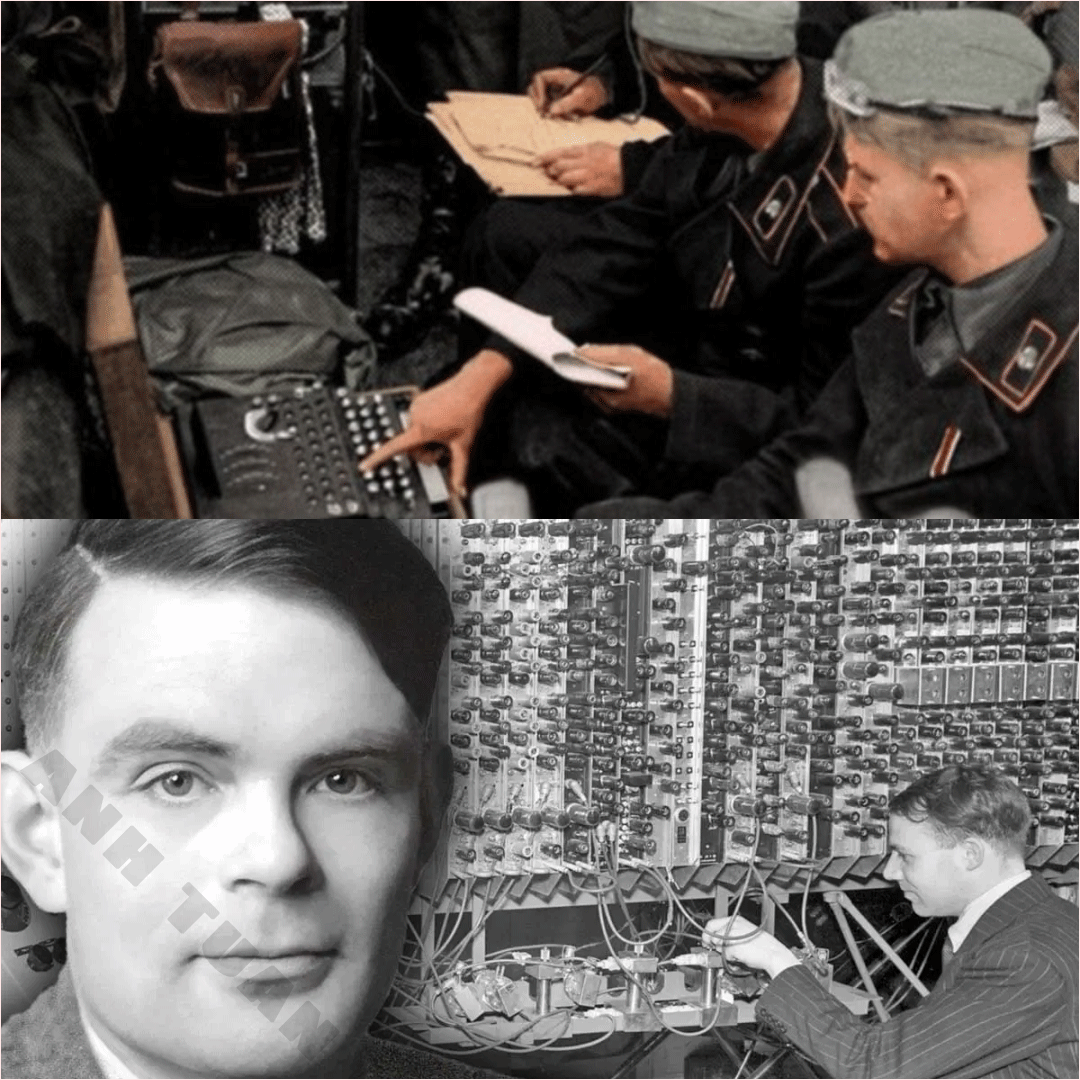

German cryptographers were not fools. Their confidence rested on calculations that looked unassailable through the lens of 1930s and early 1940s technology. The standard three-rotor military Enigma offered 17,576 possible rotor positions. Multiply that by rotor orderings and you reached over a million primary configurations. Then the plugboard added its own fog, the tangle of cable pairings that turned complexity into something that felt like eternity.

When German specialists spoke about Enigma, they did not speak like gamblers. They spoke like engineers. Security was not a matter of luck. It was a matter of arithmetic.

Dr. Erich Hüttenhain, who led the OKW/Chi cipher department, understood the theoretical possibility of attack. He understood that no system deserved worship. Yet he also understood what resources looked like, and he concluded that no enemy would rationally devote the labor required to pry open a daily-changing cipher at scale. Keys changed every midnight. Every dawn you started again. Even captured machines were useless without the day’s settings. Even captured codebooks could go stale with procedure updates. German calculations suggested that exhaustive testing would demand impossible manpower and time.

The conclusion was seductively simple.

The math says no.

The Navy built ritual on top of that conclusion until the ritual became identity. Naval Enigma operators trained for months, learning not only the machine but the habits meant to keep it safe. Codebooks were printed on special paper with ink designed to dissolve quickly in water. Weighted bags ensured materials would sink if thrown overboard. U-boat commanders carried sidearms and carried, too, a grim instruction that in certain moments, mercy could not be afforded to paperwork.

These precautions did not only protect secrets. They protected confidence. They allowed men like Dönitz to believe that an ocean of radio traffic could be sent without fear.

In early 1942, the Navy escalated its faith into something close to arrogance. The four-rotor naval Enigma, the M4, was introduced for U-boat use. Germans considered it the ultimate evolution of security. Allied codebreakers would call the new network Shark. The additional rotor and expanded rotor choices multiplied complexity. German internal assessments attempted to break their own cipher with known methods and failed. Reports returned to headquarters with calm certainty. Nothing suggests compromise. Nothing suggests weakness.

Dönitz absorbed those reports the way a commander absorbs ammunition. He needed them to be true.

And yet, while the mathematics sounded immortal, the Atlantic began sending warnings early, warnings that should have forced any rational institution to at least consider the forbidden hypothesis. The pattern did not announce itself in one dramatic moment. It emerged in “coincidences” that stacked until coincidence began to look like design.

In the spring of 1941, German supply ships positioned in remote stretches of ocean began to vanish with a precision that bordered on the impossible. These were not ships meant to be found. They were floating warehouses, fuel tankers and replenishment vessels placed in emptiness to serve surface raiders and U-boats far from coastlines. Between March and June, the Royal Navy intercepted and destroyed most of them, one after another, as if someone had placed pins on a map.

Chance discovery across millions of square miles should have been absurd. Yet German investigators reached for explanations that left their pillar standing. Improved radar. Improved ocean surveillance. Better reconnaissance. Better luck.

Anything except the possibility that the British were reading position reports.

Then came Bismarck, the ship Germany expected to become a myth.

It broke into the Atlantic like a promise. Its guns, its armor, its speed, its fire control, all of it felt like an argument for German superiority. German planners expected it to dissolve into distance and weather. Instead, British forces moved with uncanny certainty, searching in the right places at the right times, concentrating strength as if guided by an invisible hand.

From the outside, later histories would call it brilliance and luck, the genius of shadowing cruisers and the stubborn courage of sailors who refused to let the ship escape. Inside the secret world, it was something else. It was preparation enabled by foreknowledge.

German leadership framed the loss through the lens they preferred. British radar advances. Air power. Mechanical misfortune. A lucky torpedo hit that jammed a rudder. All of that was partly true, but none of it explained the deeper pattern, the timing that felt like an enemy who knew where to look.

Year after year, German commanders told themselves the same story because the alternative was unbearable.

U-boat losses climbed steadily from late 1941 onward. The numbers grew heavier, then brutal. Boats vanished on patrol lines that should have been safe. Refueling rendezvous in remote waters were struck as if the ocean itself were leaking information. Convoys slipped around wolf packs with a precision that felt almost intelligent, altering course at the last possible moment, always just beyond the net Dönitz thought he had cast.

In his war diary, Dönitz expressed frustration and mystery. He demanded investigations. He demanded technical explanations. He blamed Allied aircraft equipped with new radar systems. He imagined detection capabilities that were, at the time, technological fantasies, because fantasy was easier than admitting exposure.

Berlin fed him reassurance as if reassurance were a weapon.

An insight into our cipher does not come into consideration.

Investigations multiplied. They grew more technical, more elaborate, more desperate. Each one had the same blind spot, like a crack in a lens that makes the world blur in one exact place no matter how carefully you focus.

When U-570 surrendered after an air attack in August 1941, security questions sharpened. If cryptographic materials had been captured intact, compromise was possible. Captain Ludwig Stummel was assigned to examine implications. His work was meticulous. He interviewed survivors, reconstructed timelines, analyzed messages, and outlined what could happen if the enemy possessed a machine and current keys.

Then he dismissed the scenario.

Protocol demanded destruction, he wrote. It must be assumed crews fulfilled their duty. Even if keys were compromised, they would change soon. The cipher does not appear to be broken.

His conclusion was logical inside the world he lived in. That was the trap. The logic served the pillar rather than testing it.

What Germany could not see in full was that the British had already achieved something far more valuable than a single captured machine. In earlier boarding actions, the enemy had obtained codebooks, procedure details, and the kind of operational shortcuts that turn cryptanalysis from a mountain into a climbable ridge. German investigations treated each incident as isolated, each one framed by the assumption that Enigma remained invulnerable. Compartmentalization ensured no one owned the whole picture. Cryptographers assured commanders. Commanders assured high command. High command assured the nation.

Nobody was responsible for doubting the entire system.

By 1943, the crisis had become too loud to ignore, but still too psychologically expensive to name correctly. The slaughter of Black May forced Dönitz into his most comprehensive security review. He needed an explanation that would allow him to fix the problem without admitting the real one. The investigation team explored hypotheses with impressive rigor and impressive blindness.

First they suspected the Metox radar warning receivers carried by U-boats. German scientists tested whether these devices re-radiated signals that could betray positions. The results were alarming. Emissions could indeed be detected at long range. Orders went out. Stop using the receivers.

Losses continued.

Next they suspected infrared detection, the idea that Allied aircraft could spot the heat signature of diesel engines. German departments launched crash programs, repainted boats with experimental coatings, and tried to fight an invisible enemy with paint and theory.

Losses continued.

Then the Germans captured evidence of British centimeter-wavelength radar, technology their detection gear could not receive. This discovery felt like relief because it was real. It offered a culprit that did not require a confession. It fit the story German commanders already wanted to tell: the enemy’s machines are better than ours.

The Germans rushed new detectors toward the fleet. Yet even this real advantage did not fully explain the pattern, because radar was only the visible blade. The unseen hand was still turning the knife.

Throughout all of these investigations, one hypothesis remained notably absent from serious consideration. The Allies were reading the traffic itself.

German intelligence leaders reasoned their way out of the truth with a chain of “impossibles.” To read naval communications, the enemy would need captured machines and current keys. They would need officer-only procedures. They would need time to solve settings before midnight. They would need a perfect chain of unlikely events. Taken singly, improbable. Together, impossible.

There was also a paradox that acted like a sedative. Germany’s own cryptanalytic success against the Allies convinced them they understood the limits of the game. B-Dienst achieved real breakthroughs against British naval ciphers. German analysts read convoy communications with speed and confidence, sometimes predicting movements hours ahead. This success taught them how difficult codebreaking was, how fragile access could be, how often it failed when procedures changed.

They projected those limitations onto their enemies.

If we struggle even with captured material, they reasoned, then surely the British struggle more against our superior system. Surely they might gain occasional glimpses, but never a steady, industrial-scale reading.

What they did not understand was that the British were not playing the game like a small office of specialists. They were building an industry. They were creating workflows, training pipelines, and machines designed to exploit structural features rather than search universes. They were turning cryptanalysis from art into production.

It was not brute force. It was exploitation.

And it was fed by human behavior.

The same strict formatting requirements meant to impose discipline created predictable phrases. Weather reports repeated patterns. Routine signals carried habitual language. Operators, tired and human, made tiny mistakes that became anchors. A system that looked perfect in theory became vulnerable in practice, not because the mathematics were weak, but because war is lived by people, not by equations.

One of the cruelest ironies was that German success sometimes accelerated German defeat. When B-Dienst deciphered British convoy messages, German headquarters transmitted convoy positions and planned intercepts over Enigma networks to U-boats. Those messages, packed with known facts and predictable language, created perfect “cribs,” the kind of material British codebreakers could use to recover settings faster. Germany’s tactical intelligence victories became fuel for Britain’s strategic intelligence dominance.

The Atlantic became a hall of mirrors.

German analysts, reading British convoy codes, felt clever and powerful. British analysts, reading German operational orders and watching how Germany exploited stolen British information, gained an even clearer picture of German intent. U-boats sailed into traps that felt like fate because they were shaped by foreknowledge.

The preservation of Ultra, intelligence derived from broken Enigma traffic, required something as difficult as the codebreaking itself: restraint. British leaders understood that the advantage of reading German communications outweighed any single tactical strike. If Germany became convinced the cipher was compromised, procedures would change, networks would go dark, and the war could stretch longer and bloodier.

So the British built an architecture of deception as careful as any fortress. They invented cover stories, including fictitious spy networks meant to explain sudden “discoveries.” They conducted reconnaissance flights not because they needed to see, but because they needed to be seen. They staged “chance” encounters so that success would look like luck. They timed attacks only after plausible detection opportunities. They calibrated action and inaction with cold discipline.

Sometimes preserving Ultra meant accepting loss. That truth sat like a stone in the stomachs of those who knew it. It also required silence afterward. Thousands of people returned to civilian life unable to explain what they had done, forced to listen to incorrect histories without correcting them, forbidden even to tell spouses why certain years of their youth could never be described.

Across the Atlantic, the United States became part of that discipline. Intelligence officers who had received pieces of the product understood the price of it. Later, in Washington’s training rooms, the story would be taught as a lesson not only in cryptography but in psychology. The most dangerous enemy is often the certainty that stops you from asking the one question that could save you.

In 1943, Dönitz had no such lesson. He had only rising numbers and sinking confidence.

By May 1943 he commanded the largest U-boat fleet in history. Wolf packs patrolled the North Atlantic like predators with names that looked almost harmless on paper. He believed victory was still possible. He wrote of the enemy showing signs of exhaustion. One more concentrated effort, he believed, and the Atlantic supply line would crack.

What he could not know, what his entire command system prevented him from knowing, was that his greatest innovation had become a beacon.

Centralized radio control required constant communication. Every boat reported position, fuel, torpedo inventory, contact. Dönitz orchestrated attacks like a conductor, directing steel instruments across a black sea. The more precisely he controlled, the more radio traffic he generated. The more he transmitted, the more he fed the enemy’s listening.

And in the hidden world behind British hedgerows, shifts ran through the night. Operators transcribed intercepts. Analysts searched for cribs. Machines tested hypotheses at speeds that would have sounded like science fiction to German investigators. Results moved through controlled channels to commanders at sea and planners on land.

Convoys were routed around assembly points. Hunter-killer groups were vectored toward refueling rendezvous. Escorts were reinforced not because someone guessed, but because someone knew.

German submarines still sank ships. War did not become painless. But the exchange rate turned. Boats went down in clusters. Commanders with multiple patrols vanished with their crews. New crews died on their first mission. The Atlantic, once a hunting ground, became a grave.

To the German mind, it looked like the enemy had suddenly become omnipresent. To Dönitz, it looked like the Allies had finally perfected the net. To his investigators, it looked like radar and aircraft had reached a level that made submarine warfare nearly impossible.

The simplest explanation was the one they could not bear.

That the enemy was reading them.

And decades later, in a modest room in West Germany, with a book open on his desk, Dönitz met that explanation at last. He met it not as a theory, but as a sentence printed in ink, calm and final, carrying the weight of thousands of drowned men.

His face drained of color, his aide would later say. He sat in stunned silence, feeling the cruel shift of the past. The war he believed he had fought did not vanish, but it changed shape. The Atlantic did not become kinder. The dead did not come back. What changed was the meaning of loss.

Radar and resources had mattered, yes. But the deeper wound was this.

He had not been beaten only by steel and numbers. He had been beaten by the fact that his most secret communications had been transparent, and the certainty that kept him from suspecting it had killed more of his men than any depth charge ever dropped.

News

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

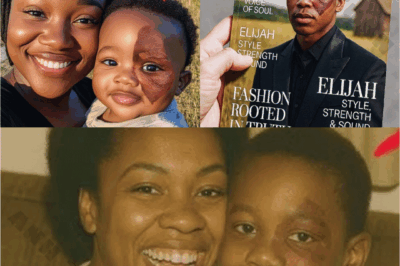

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load