Karl folded the scrap of paper twice, then a third time, until it was small enough to fit into the envelope the camp issued for letters. The pencil nub had smudged his fingertips gray, and he rubbed them against his trouser leg the way he’d done as a boy after helping his father in the workshop. He stared at the words as if the act of looking could make them truer, could make the distance between this barracks and whoever might read them feel smaller.

He did not write about politics. He did not write about blame. He wrote about weather, because weather was honest, and about hands, because hands told the truth even when mouths didn’t.

In the morning he joined the line at the little office where mail was collected. A guard took the envelope without looking at him, stamped something, and tossed it into a tray with dozens of others. The envelope looked fragile there, a paper boat set on a wide, indifferent river.

Karl walked away without turning back. Hope, he’d learned, was easiest to carry when you didn’t stare at it too long.

By April, the snow was no longer a solid thing. It softened and sank into itself, turning the camp’s paths into slush and then mud. The men tracked it into the barracks in thick clumps, and the floor became a mess that smelled of wet wool and old wood. The wind still arrived sharp some mornings, but it no longer felt like a threat that could finish you without effort.

Spring did not make anyone free. It simply reminded them the world kept moving, even when you were stuck behind wire.

Work details changed with the season. The snow crews became repair crews. Fences needed mending. Ditches needed clearing. Fields needed hands. The town nearby woke up in the way towns did, not with speeches, but with chores. Seed sacks. Tractor repairs. A new set of tires on a truck. A church bake sale posted on a bulletin board.

Karl noticed these things the way a starving man notices food, quietly, reverently, with a careful hunger.

The first time they passed a schoolyard on a work detail, the sight surprised him so much he almost stopped walking. Children ran in circles on grass that was still half brown, half green, screaming in that careless way only children could afford. Their coats were open. Their hands were bare. They did not look like they were waiting for the next siren.

A little girl fell and popped back up like a rubber ball, laughing, and Karl felt something odd behind his ribs, a pressure that was not pain, exactly, but close enough to make him swallow hard.

He kept his eyes forward, because guards noticed lingering looks. Even a harmless longing could be misread.

Harold’s farm became familiar in a way Karl did not entirely trust. Familiar things had been taken from him before, and the mind learned to grip anything good with suspicion, as if suspicion could keep it from disappearing.

Harold did not grow softer, but he grew consistent, and consistency was its own kind of mercy. He spoke to the prisoners like you spoke to men who could do work, not to monsters you kept at arm’s length. He taught without calling it teaching. He corrected without humiliating.

When the days warmed, Harold brought out a jug of water wrapped in cloth to keep it cool. He set it down on an overturned crate and waved the prisoners toward it with a jerk of his chin.

“Drink,” he said. “You get stupid when you’re thirsty.”

Karl took a tin cup and drank, slow and steady. The water tasted clean, almost sweet compared to what he remembered from the last months back home. He felt the urge to look up and say something meaningful. Instead, he simply nodded once, because in this place, understatement felt safer than emotion.

One afternoon, a storm rolled through with sudden violence. The sky darkened like a lid lowered over the world, and wind shoved at the barn doors hard enough to make the hinges groan. Harold cursed and waved everyone inside. The prisoners crowded under the shed roof with the guard, all of them listening to rain slam the metal like fists.

Lightning cracked in the distance, and the air smelled of wet earth and old hay. Karl stood with his back against a wooden post, feeling the vibrations of thunder through his boots. The guard shifted his rifle, uncomfortable, and for the first time Karl noticed that the guard was young, younger than Karl had realized, with a tiredness in his face that didn’t come from boredom.

Harold stepped close to the guard, voice low.

“Boy,” he said, not unkindly, “you look like you could use coffee.”

The guard blinked, then muttered, “Can’t.”

Harold snorted.

“You can,” he said. “You just won’t.”

The guard’s jaw tightened. He glanced at the prisoners as if worried someone would interpret the offer as weakness. Harold didn’t care. He walked toward the house anyway, boots splashing through puddles.

When he came back, he carried two mugs, steam rising from both. He handed one to the guard first. The guard hesitated, then took it like it was contraband.

Harold handed the other mug to Karl.

Karl froze. He didn’t reach out immediately, not because he didn’t want it, but because he didn’t understand the shape of the moment. He had been given coffee before, yes, but always in a way that stayed inside the boundaries of prisoner and captor. This was different. This was Harold deciding, with a kind of blunt fairness, that in a storm, warm hands mattered more than categories.

Karl took the mug.

“Danke,” he said without thinking.

Harold’s eyes flicked up.

“That’s what I figured you’d say,” he replied, as if he’d been expecting the word all along.

They stood in the storm’s shadow, three men drinking coffee while rain hammered the roof. The scene felt impossible and ordinary at the same time, and Karl realized that the most confusing thing about America wasn’t the abundance. It was the way the people here could behave as if contradictions were simply part of life.

Harold spoke again, nodding toward the guard.

“You got a name?”

The guard frowned, then cleared his throat.

“Tom,” he said, voice quiet.

Harold grunted.

“Well, Tom,” he said, “storm don’t care if you’re wearing a uniform or not.”

Tom’s mouth twitched. It might have been the beginning of a smile. It might have been relief.

Karl watched, not daring to move too much, as if the whole fragile normal moment would shatter if he breathed wrong.

After the storm passed, the world smelled new, rinsed clean. Sunlight returned in slices through clouds. Puddles shimmered. Birds appeared as if they’d been waiting behind the sky’s curtain.

They went back to work without ceremony.

Later that week, the boy with the sled appeared again, this time without the sled. He stood near the fence line with his hands shoved into his pockets, rocking on his heels. Harold was inside the barn, and Tom leaned against a post nearby, rifle slung loosely.

The boy looked at Karl with the same blunt curiosity, but there was something else now, a kind of stubborn courage.

“You eat it?” the boy asked.

Karl understood after a beat.

“The biscuit,” Karl said, careful. He nodded. “Yes.”

The boy’s face relaxed with satisfaction, as if Karl eating the biscuit had proven something important.

“My brother wrote,” the boy said quickly. He looked away, staring at the barn wall like the words were too heavy to hold in his face. “He’s in France. Says it’s wet. Says everything smells like smoke.”

Karl swallowed. He did not know what to do with that information. Sympathy felt complicated when you were on opposite sides of the uniform.

The boy looked back at Karl again, eyes searching.

“You got family?” he asked.

Karl hesitated, then nodded once.

“My mother,” he said. “And my brother. But… I don’t know.”

The boy’s shoulders fell slightly, as if he recognized the shape of that not knowing.

He dug into his pocket and pulled out a small object, then held it out.

It was a pencil, brand new, yellow lacquered, the kind used in schoolrooms. Karl stared at it, stunned by its simplicity. A pencil was nothing, and in a war, a pencil was proof that somewhere, children still learned to write instead of learning to hide.

“For letters,” the boy said, words tumbling out like he was afraid of being stopped. “So you don’t have to use those nubs.”

Karl looked at Tom, unsure whether this was allowed. Tom stared at the pencil, then lifted his gaze to the horizon as if he suddenly found the clouds interesting. He did not move.

Karl took the pencil. His fingers closed around it with a care usually reserved for glass.

“Thank you,” Karl said.

The boy nodded, then stepped back as if embarrassed by the softness of the exchange.

“My mom says you’re people,” the boy blurted, then immediately looked horrified, as if he’d just revealed a secret.

Karl’s throat tightened. He didn’t trust his voice. He nodded again.

“Yes,” he managed. “We are.”

The boy turned and ran off, boots thudding on wet ground, leaving Karl holding a pencil and the strange feeling that his life, however fenced in, had brushed against something innocent again.

That night, Karl wrote another letter. He wrote slower, neater, as if the fresh pencil demanded respect. He wrote about the storm and the coffee, but he also wrote about mud and birds and a boy who was learning, in his own clumsy way, that enemies still had mothers.

He did not know if these letters would arrive. He wrote anyway, because writing was a way of keeping your mind from freezing, even when the weather warmed.

As spring deepened, the camp changed in small ways. The air smelled less like coal and more like grass. The men’s faces relaxed slightly, the lines around their mouths softening. Someone planted a few seeds in a corner near the barracks, not because they expected permission, but because humans planted things when they needed to believe in next seasons.

The guards changed too, though they pretended they didn’t. Some still barked orders like they wanted to keep the world rigid. Others, like Tom, let their shoulders drop in moments when no one important was watching. Karl saw Tom accept a piece of pie one afternoon from a woman on a farm, and the way Tom’s eyes closed for a brief second as he tasted it told Karl everything.

Food was never just food. It was the body remembering it belonged to life.

One Sunday, the camp chaplain held a service in a small hall. Karl did not go for faith. He went for quiet. The hall smelled of dust and old wood. Men sat on benches and stared at their hands. A few sang, their voices hesitant, rough. The chaplain spoke in English, but someone translated. The words were familiar, the kind that had been repeated for centuries in every war.

Comfort. Mercy. Home.

Karl listened, not entirely believing, but grateful for the permission to sit still without being judged.

After the service, the chaplain a thin man with kind eyes approached Karl.

“You write letters,” the chaplain said, as if it were a gentle accusation.

Karl tensed. He didn’t know what trouble writing could cause.

“Yes,” Karl said.

The chaplain nodded.

“Good,” he said. “Keep writing. It keeps a man from disappearing.”

Karl looked at him, startled by the phrase.

“Disappearing,” Karl repeated.

The chaplain’s expression softened.

“War has a way of turning people into numbers,” he said. “Writing turns you back.”

Karl didn’t know how to respond to that. He nodded once and walked away with the words sitting in his chest like a stone that was heavy but strangely steady.

By early summer, the work details stretched longer into the evening. The sun lingered, refusing to let the day end. The fields turned green. Corn rose in straight rows, bright and impossible, and Karl found himself thinking of other camps he’d heard about, where prisoners had stared at yellow ears of corn as if it were animal feed.

He understood that reaction. Hunger and fear could make generosity look like a trick. Your mind learned to protect you by suspecting everything.

One afternoon, on a farm farther out, a woman set a basket on a table under a tree and waved the work crew over. Inside were sandwiches thick with meat and pickles, apples, and a jar of lemonade that sweated in the heat.

The prisoners approached cautiously at first, then ate with the quiet intensity of people who didn’t waste calories on pride. The lemonade was sharp and sweet, and Karl had to blink hard after the first sip because sweetness still felt like something from a different life.

The woman watched them without smiling too much, as if smiling might make the moment feel like a performance.

“You boys work hard,” she said.

Karl caught the word boys and felt the strange sting of it. He wasn’t a boy. He was a man who had seen too much. But the word held no insult. It held the plain tone of someone addressing people as people.

Tom stood off to the side, holding his own cup. He didn’t drink at first. Then, when he thought no one was watching, he took a sip and his shoulders dropped.

Karl understood, then, that Americans were not untouched by war. They were simply farther from its rubble. Their fear arrived in letters from overseas, in telegrams, in the empty chair at the dinner table when a son didn’t come home. Their grief was quieter, but it was still grief.

That realization did something in Karl that he did not tell anyone about. It loosened the old story he’d been fed, the story that said enemies were made of a different kind of blood.

Weeks later, Harold asked Karl, blunt as always, “You ever seen a baseball game?”

Karl frowned. He knew the word baseball, but not the thing.

“No,” Karl said.

Harold pointed toward town with his chin.

“They play on Fridays,” he said. “It’s just kids. But it’s something.”

Karl wasn’t sure if the invitation was real. He wasn’t sure if it was even allowed.

Tom answered without being asked, voice quiet.

“It’s allowed,” he said. “If the commander signs off. Supervised.”

Harold shrugged as if paperwork was a small inconvenience, not a barrier.

“Then get the paper signed,” he said. “You’ll sit, you’ll watch, you’ll be bored, and you’ll go back. But you’ll have seen something normal.”

Normal. The word landed strangely. Karl had forgotten how much he missed being bored for harmless reasons.

The following Friday, a small group of prisoners was taken into town under guard. They walked past storefronts with big windows and signs painted in careful letters. A barbershop pole turned. A diner buzzed with voices. A drugstore advertised ice cream. Someone swept a sidewalk as if sweeping was the most important task in the world.

Karl’s heart thudded hard, not from fear of escape, but from the shock of being among ordinary life again. He kept his hands visible. He kept his face neutral. He did not want to draw attention to himself the way a wounded animal tried not to limp.

The baseball field sat behind a school, grass trimmed and bright under late sunlight. Wooden bleachers creaked as people sat down. Families gathered with paper bags of peanuts. Boys in uniforms shouted to each other, their voices high with excitement and nothing else.

Karl sat on the bleachers with Tom a few steps behind. Harold stood near the fence line like a man pretending he wasn’t proud of his town.

A boy stepped up to bat, lifted his chin, and swung too early. The crowd laughed, not cruelly, but warmly. The boy grinned and tried again.

Karl found himself watching the way Americans cheered, not just for perfection, but for effort. He watched a father clap even when his son struck out, and something inside Karl tightened with a longing that felt almost unbearable.

Harold leaned close enough to speak without making it seem like a conversation.

“See?” he said. “World keeps going.”

Karl nodded, unable to speak.

On the walk back to the truck, a woman approached the guard with a small bag. Tom stiffened, unsure. The woman didn’t look at the prisoners directly, not out of contempt, but out of shyness, as if she didn’t know the rules of this strange new situation.

“For them,” she said to Tom, holding out the bag. “They can have this. If it’s allowed.”

Tom looked at the bag, then at Karl, then at Harold.

Harold said, “It’s peanuts, Tom. Not dynamite.”

Tom’s mouth twitched. He took the bag and nodded.

“Thank you, ma’am,” he said.

Back in the truck, Tom handed the bag to Karl without meeting his eyes.

Karl opened it and saw small paper cones filled with roasted peanuts. He passed them to the men beside him. They ate slowly, cracking shells, tasting salt and smoke and something that felt like belonging to the human world again.

That night in the barracks, men who had not smiled in months told each other, quietly, about the game. They described the way the ball cracked against the bat. They described the laughter. They described the children chasing a foul ball into the grass like nothing in the world mattered more than catching it.

Someone said, “It’s strange.”

Karl asked, “What?”

The man shook his head, expression uncertain.

“That we are here,” he said. “That they live like this while our cities burn.”

Karl had no answer. The contradiction was real. It sat in the room with them. It did not go away because you wanted it to.

Still, something in Karl had shifted again. Not into gratitude that erased pain, not into forgiveness that ignored what had happened, but into a clearer understanding of what the chaplain had meant.

War made people into numbers. Small moments made them back into men.

When summer began to tilt toward fall, Karl received a letter.

It was thin, foreign paper, the handwriting familiar enough that his knees went weak. He sat on his bunk and stared at the envelope for a full minute before opening it, as if opening it might change what it contained.

It was from his mother.

The words were short. The lines were uneven. She wrote about a roof that leaked. She wrote about a neighbor who shared potatoes. She wrote about the church bell that had survived even when the windows had shattered. She wrote about his brother, alive, thin, back home, working when he could.

At the end she wrote a sentence that made Karl’s vision blur.

We pray you keep your heart.

Karl lowered the paper and stared at the floor until his breathing steadied. Around him, the barracks continued as if nothing had happened. Men argued over cards. Someone coughed. Someone laughed at a joke Karl didn’t hear.

Karl folded the letter carefully and put it under his pillow like a talisman. He did not cry. Not because he didn’t want to, but because tears felt like something that would open him too wide. He sat still and let the relief move through him, slow and heavy, until it became part of him.

The next day on Harold’s farm, Karl worked with a different posture. Harold noticed, because Harold noticed everything.

“You got news,” Harold said.

Karl hesitated, then nodded.

“My mother,” he said. “She lives.”

Harold’s expression softened in a way so quick Karl almost missed it.

“That’s good,” Harold said, voice rough. “That’s real good.”

Karl swallowed. He didn’t know how to explain the storm of feeling in his chest, the way relief and guilt tangled together. He didn’t try. He simply worked, and the work felt, for once, like something that could carry him forward instead of keeping him pinned.

As the days shortened again and the air began to sharpen at night, Karl realized something that would have horrified him the previous year.

He was no longer terrified of winter.

He respected it. He understood it. He knew how to survive it.

He also knew something else now, something that felt almost more dangerous than cold.

He knew that ordinary people could change the atmosphere of captivity without ever making headlines.

A scarf. A towel. A biscuit. A pencil. A cup of coffee in a storm. A bag of peanuts handed over like it was nothing.

Small things, steady things, real things.

And because they were real, they stayed.

News

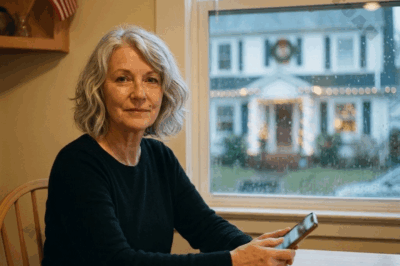

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

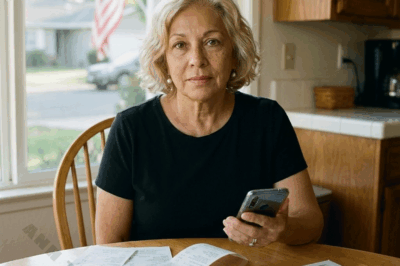

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

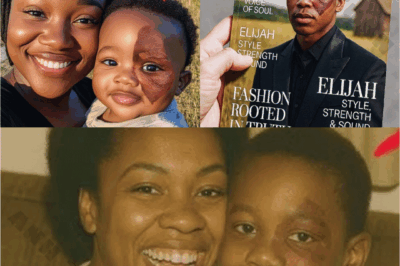

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load