In the spring of 1945, Europe didn’t step into peace so much as it staggered there, bruised and blinking, like someone forced awake after too many nights and told to keep moving anyway. The war ended on paper before it ended in people. Smoke still clung to certain streets as if it had learned the shape of them. Brick dust lived in the cracks of sidewalks. Borders were more suggestion than certainty, and whole towns were learning how to exist without the rules that had once kept them upright.

Thomas Ward was twenty-four when the fighting finally stopped, though his reflection in any broken window made him look older. His uniform hung a little looser than it should have. His face held a calm that wasn’t calm at all, just a kind of practiced stillness that came from living too long in places where sudden movement could cost you. People at home would later tell him he looked “steady” in photographs. He would never explain that steadiness was something he’d learned the way you learn to hold your breath.

He expected to go home quickly, the way most of them did. He expected to step onto English soil and feel something in him unclench. He expected to sleep without waking to invisible noises. He expected the past to stay where it belonged, on the far side of the Channel, behind him.

Instead, he stayed.

There was work to do, the kind no one put in the speeches. Occupation duties. Lists. Schedules. Rations. Stamps. The war had collapsed loud, but the after-war rebuilt itself quietly, in offices set up inside buildings missing windows, on tables shoved beneath crumbling plaster, with men in uniforms trying to sound certain while the world around them looked like it had been chewed up and left behind.

That was where he met Anna Krüger.

He first noticed her in a municipal building that had once been grand and now felt like a hollow shell of authority. The corridors smelled of damp stone and cheap disinfectant. A British captain was speaking too loudly to a cluster of local clerks, his voice bouncing off bare walls as if volume might translate itself. Thomas stood near the doorway, waiting for his turn to be useful, watching the captain’s mouth move while his own mind drifted toward the simple fantasy of a bed that didn’t shake when trucks drove past.

Then the woman spoke.

Her English didn’t wobble. It didn’t strain. It landed cleanly, precise and calm, correcting a date the captain had gotten wrong without humiliating him. She didn’t raise her chin. She didn’t smile. She simply said what was true, as if truth were the only luxury left worth keeping.

The captain blinked, recalculated his pride, and moved on.

Thomas lingered after, pretending he’d been given another task. He told himself he was staying because someone might need him. In reality, he wanted to hear her speak again, because her voice had the steady cadence of a door closing in a storm.

The woman turned, caught him looking, and her gaze narrowed just slightly. Not hostile. Appraising. Like someone who had learned that every new face required a quick assessment: threat, opportunity, complication.

He cleared his throat, and immediately hated himself for how small it sounded against the ruin of everything.

“Your English is very good,” he said.

Her expression didn’t change much, but something in her eyes acknowledged he was speaking to her as a person, not as a function. “I studied it,” she replied. “Before.”

Before. The word carried a whole country inside it.

Thomas nodded, and then because silence felt like surrender, he offered his name. “Thomas. Corporal Ward.”

A beat of hesitation, as if she were deciding whether giving him her name would cost her anything. “Anna,” she said at last. “Anna Krüger.”

Krüger. German. Heavy. Still sharp in British ears in 1945. Thomas should have walked away. He didn’t.

“Do you live nearby?” he asked, and the moment the question left him he realized how foolish it was. As if anyone lived anywhere by choice anymore.

Anna’s mouth tightened. “I live where I’m allowed,” she said.

The honesty of it hit him harder than anger would have. He didn’t apologize. He didn’t try to soften it. He simply nodded, because in his own uniformed way, he understood that living where you were allowed was what everyone was doing.

Over the next weeks, circumstance kept placing them in the same rooms. Thomas was assigned to duties that required translation. Anna’s fluency made her valuable, and being valuable was a kind of protection. She moved through the chaos like a person balancing a glass of water across broken ground, careful and controlled, refusing to spill what little steadiness she had left.

Their first conversations were formal. All dates, names, instructions. He asked questions. She translated. He thanked her. She nodded. Then something shifted in the pauses between tasks. A glance that lasted a second too long. A shared exhale after a meeting that went badly. The tiny relief of a joke that landed.

One afternoon, rain turned the streets into slick ribbons of mud, and Thomas found Anna in a doorway, staring out at the gray drizzle as if she could read the future in it. He stood beside her, shoulder close but not touching.

“You don’t like the rain?” he asked.

Anna’s gaze stayed on the street. “I don’t trust it,” she said. “When it rains, people move differently. They hurry. They make mistakes.”

Thomas almost smiled. “That’s very practical.”

“It is survival,” she replied, and then, after a beat, she added, quieter, “What do you miss?”

The question caught him off guard. People didn’t ask soldiers what they missed. They asked if they were proud, if they were brave, if they were glad it was over. Missing implied softness, and softness was something the war had punished.

Thomas stared at the rain until his throat loosened enough to answer. “Silence,” he said. “Real silence. Not the kind that comes before shelling.”

Anna nodded as if she understood perfectly, and that was the first time Thomas felt a thread connect between them that wasn’t language, wasn’t duty. It was something deeper. Recognition.

He began to notice details. The way she drank her coffee too strong, as if bitterness kept her awake. The way she kept her hair pinned back severely, not out of vanity but practicality, as if loose strands were a risk. The way her hands were always busy, sorting, folding, smoothing. A woman who had learned that order was the closest thing to control.

Anna began to notice him too. The way he flinched at slammed doors even when he tried to hide it. The way he ate quickly without tasting, then looked ashamed afterward. The way he could be kind without making a performance of it, the way he stepped aside to let others pass even when the world had trained men like him to take space.

Their relationship, when it became one, did not announce itself. It simply grew in the spaces between official business. A walk back to the makeshift office. A shared cigarette outside a doorway. A quiet conversation in a corner while other people argued over ration slips and authority as if paper could replace food.

Thomas did not tell himself he was falling in love. He told himself he was lonely. He told himself he enjoyed talking to someone competent. He told himself this would end when he went home.

Then one late afternoon, after a meeting in a cold room where men bickered over lists, Anna walked with him down a street lined with broken bricks. A child ran past carrying a tin can, laughing, and the sound echoed oddly against the ruins, like joy had gotten lost and was surprised to find itself still alive.

Anna stopped and watched the child with a look Thomas couldn’t name at first. Not jealousy. Not sadness. Something like disbelief.

“She shouldn’t be laughing,” Anna said, almost to herself.

“She should,” Thomas replied, and then because the war had made him blunt when it mattered, he added, “Would you come with me, if I asked?”

Anna turned to him slowly, her face unreadable. “Where?” she asked.

“England,” he said, and the moment he said it he understood how absurd it sounded, as if England were a clean room untouched by war. England had its own rubble, its own grief, its own rationing. But England meant home, and home had become a magnet he didn’t know how to resist.

Anna swallowed. “And what would I be in England?” she asked quietly.

Thomas heard the fear under the question. Not just fear of hatred, but fear of being trapped in someone else’s story. German war bride. Enemy wife. Trophy. Burden. He had seen how easily people turned labels into cages.

“You’d be my wife,” he said.

The word hung between them, fragile and heavy at the same time. Anna’s eyes flickered, and for the first time Thomas saw the composure crack just enough to reveal something raw underneath.

Hope, edged with terror.

They married later that year in a small ceremony that felt almost clandestine, a room borrowed from a local office that still smelled faintly of damp plaster and disinfectant. Thomas wore his uniform because he owned nothing else that looked respectable. Anna wore a simple dress borrowed from a cousin who had been saving it for a wedding that kept getting postponed by war and loss.

A chaplain spoke the words. Anna’s English held steady through the vows, though her voice trembled once when she said yes. Thomas squeezed her hand too hard, and afterward he felt guilty because the squeeze had been as much about his fear as his love.

There was tea served in chipped cups. A few biscuits. Someone offered a toast that sounded more like relief than celebration. Anna smiled politely, then stepped outside into cold air and stared at the broken skyline as if she were saying goodbye without allowing herself to look back.

Thomas believed the war was behind them.

He was only half right.

England was not the clean restart he’d imagined. It was better, yes. Safer. But it was still wounded. Streets were rebuilt and still smelled like soot when it rained. Rationing lasted. Men came home and tried to become husbands again. Women tried to become wives again. Everyone pretended normal was waiting just around the corner, as if pretending could make it true.

Thomas brought Anna to his mother’s small house in Kent first, because there was nowhere else to go while he found work. The village looked at Anna the way villages look at anything unfamiliar: with curiosity disguised as politeness and judgment disguised as concern.

Thomas’s mother, Edith Ward, was a practical woman with hands rough from work and a stare that could pin a man to the wall. She opened the door, took one look at Anna, then looked at Thomas.

“This is her,” Thomas said, and his voice betrayed him with how much he needed his mother not to turn this into a battlefield.

Edith studied Anna for a long moment. Then she stepped aside. “Well,” she said, not unkindly, “come in before you freeze.”

Anna removed her shoes carefully at the doorstep, a habit she would keep even after she learned English floors didn’t always require it. She stood in the parlor with her hands clasped as if she were trying not to take up space.

Edith handed her a cup of tea. “Sugar?” she asked.

Anna hesitated, then shook her head. “No, thank you.”

Edith watched her drink, watched the way her fingers held the cup steady despite the tremor in them. Then Edith said, quietly, “My son has nightmares. Don’t take it personally.”

Thomas felt heat rise in his face. “Mum,” he warned.

Edith didn’t flinch. “It’s the truth,” she said. Then she looked at Anna. “If you’re staying, you’ll need to know. He doesn’t shout. He goes quiet. Sometimes quiet is worse.”

Anna met Edith’s gaze, and something passed between the two women, a frank recognition that life was not a romance and survival left marks.

“I understand,” Anna said softly.

She didn’t, not fully, but she understood enough.

They moved into a modest house after Thomas found steady work. Two rooms, drafty windows, a small kitchen where Anna began to create routine like it was sacred practice. She learned quickly how to stretch rationed butter and how to make soup from almost nothing. She learned English manners, the way women asked sharp questions while smiling. She learned how to answer without giving them blood.

“Where are you from?” neighbors would ask, eyes bright with curiosity.

“Germany,” Anna would reply, and then she would add, “a long time ago,” as if time could soften it.

She rarely spoke about her homeland. Thomas rarely asked.

It became an agreement without words. The past stayed where it belonged, on the far side of a door neither of them opened.

Then the first child came.

It was winter, and the hospital smelled of boiled linens and antiseptic, the kind of smell that made Thomas’s stomach knot because it reminded him of field stations and the thin line between life and loss. He stood beside Anna’s bed and watched her face twist with pain, and his hands shook with helplessness because he had survived war and still couldn’t do anything about the simple fact that childbirth was its own battle.

When their son finally arrived, small and red and furious, Thomas let out a sound that might have been a laugh or a sob. Anna held the baby with a steady grip, her face calm again, but her eyes had a sheen that made Thomas’s throat burn.

“Peter,” Thomas whispered, because he wanted a strong name, a name that belonged fully to England, a name that would anchor this child in a world where people were still suspicious of half-German blood.

Anna nodded. “Peter,” she repeated, and the way she said it made it sound like a promise she was afraid to break.

A daughter followed, Margaret, born in the early 1950s when life was beginning to feel more ordinary, when the ration books were finally put away, when the village had learned that Anna was not leaving and that she could make apple tart as well as anyone else. Margaret grew up with Anna’s carefulness and Thomas’s quiet. She asked questions the way children do, blunt and innocent.

“Mum, why don’t we visit Germany?”

Anna would smile and say, “Because here is home,” and then she would change the subject with the smooth skill of a woman who had practiced not answering.

As years passed, Thomas noticed small things.

Letters Anna wrote and never sent, folded and hidden in a drawer. Names she avoided. Certain dates that made her quieter, especially in early summer. He assumed it was grief. Family lost. A country altered. The life she might have had if history had been kinder.

That assumption allowed both of them to keep going without disruption.

Anna never contradicted it.

Silence, she understood, could be protection.

Thomas, for his part, believed he was being loving by not asking. He told himself loyalty meant letting the past rest. He didn’t know he was also benefiting from that silence. He didn’t know the quiet he loved was, for Anna, something she paid for every day.

Some nights, long after the children were asleep, Thomas would wake and find Anna sitting at the kitchen table with the radio turned low, listening to late-night programs in German. When he asked what she was doing, she would say, “Just listening,” and she would not elaborate. Thomas would sit with her for a few minutes, the two of them sharing a darkness that felt too full, then he would go back to bed, pretending the silence was a choice rather than a necessity.

Their children grew, and with them, life expanded beyond the narrow borders of survival. Peter became ambitious, restless, the kind of boy who wanted London lights and opportunity. Margaret had a gentler steadiness, but she carried a curiosity that made Thomas worry because curiosity had a way of tugging at doors that were best left closed.

Margaret met Daniel Hayes at a small event in London, one of those gatherings that seemed ordinary until it quietly changed the shape of a life. Daniel was American, working in Britain for a company that had sent him overseas like it was nothing. He had an easy confidence, a smile that arrived quickly, and the habit of saying things like “No problem” even when there was clearly a problem, as if optimism were a muscle he’d trained since childhood.

He brought Margaret to meet her parents on a crisp autumn weekend, arriving with flowers for Anna and a bottle of whiskey for Thomas. Thomas watched Daniel step into the house like he belonged, watched him shake hands firmly, watched him compliment Anna’s roast without sounding like he was doing her a favor.

“He’s loud,” Thomas muttered later when Daniel stepped outside to make a phone call.

Anna’s mouth twitched. “Yes.”

“American,” Thomas added.

Anna’s eyes softened. “Yes.”

There was affection in it. There was relief too, as if America represented distance, not just in miles, but in history. A continent that had not held her past in its soil the same way Europe did.

Margaret married Daniel, and soon the letters began to arrive with American stamps. Then phone calls, expensive at first, then easier. Margaret’s voice would crackle through the line, bright with excitement, describing their neighborhood, their home, the way people put flags outside without irony.

“Come visit,” she urged. “Just for a few weeks. You’ll love it. It’s different.”

Thomas almost laughed at the word different. Everything was different. But he heard what Margaret meant. Different kind of air. Different kind of memories. A place where Anna could walk into a shop and not feel her accent turn heads with suspicion.

They visited Massachusetts in the late 1970s, and Thomas found himself surprised by how ordinary it felt. Not in a dull way, but in a comforting way. Streets lined with trees that turned red and gold like the world had decided to dress up. Houses with porches and neat lawns. People who smiled at strangers like smiling cost nothing.

Anna adjusted faster than Thomas expected. She liked the grocery stores filled with abundance, the simple miracle of shelves that stayed stocked. She liked the library, where she could check out books without anyone asking why she wanted English poetry. She liked that her German did not sound like the enemy here. It sounded like Europe, far away, an accent people found interesting instead of threatening.

On the Fourth of July during a later visit, Margaret’s neighborhood bloomed with harmless celebration. Small American flags appeared in gardens and on mailboxes. Sparklers hissed in children’s hands. The smell of grilled food drifted through air warm enough to make you forget winter existed.

Thomas sat on the porch with a beer, watching children laugh, and felt a strange ache in his chest. He thought of Anna in 1945, standing in ruins watching a child laugh like it was impossible. He thought of how long it took for laughter to feel safe.

Anna stood beside him holding a bowl of strawberries. She looked like she belonged, and that surprised him. He had spent years worrying the past would always pull at her like a tide. Here she looked almost at ease, her posture less guarded, her eyes less wary.

Margaret began to ask, gently at first, then more directly, if they would consider moving closer. Not forever, she said, just near enough. Life, she reminded them, did not offer endless time.

Thomas resisted at first. England was his ground. England was where he had built his quiet life. It was where his mother was buried. It was where the ghosts knew his name.

But retirement arrived, and with it a slow emptiness. Work had been a shield. Without it, memories got louder in the gaps. He found himself sitting too long at the kitchen table, staring out at the garden without seeing it, the hum of silence turning from comfort into something else.

Anna watched him in the evenings, sitting too still.

“Perhaps,” she said one night, carefully, “we can try.”

So they moved.

Not with drama, not with speeches, but with the practical momentum of people making a late-life decision. They sold the modest English home. They packed boxes. They shipped furniture and photographs across the Atlantic. Thomas joked about learning to drive on the wrong side of the road, and Margaret laughed too loudly, like she needed the joke to hold the fear down.

In Massachusetts they bought a small house in a quiet neighborhood. White siding. A front porch. A backyard big enough for grandchildren to run in. A mailbox shaped like a barn because America had a talent for turning everything into decoration.

Neighbors brought casseroles and banana bread. They asked Thomas about his accent. They asked Anna where she was from and listened politely when she said, “Germany, long ago.”

Thomas joined the local VFW, not because he loved talking about the war, but because he found comfort in sitting in a room with men who understood the same silences. It wasn’t the stories that mattered. It was the fact that no one asked you to explain the pauses.

Anna found a small garden plot and began planting as if she were stitching herself into the soil. She made friends slowly, cautiously, with women who didn’t know her history and didn’t demand it. In America, people loved reinvention. It made it easier to be new.

Thomas began to believe the past had finally closed its door.

Then, forty years after 1945, the knock came.

It was a quiet winter afternoon, the kind where the light looked thin and pale, as if the sun was tired too. The house was still. The world felt predictable. Thomas was reading the newspaper at the kitchen table while Anna rinsed dishes, the two of them moving in the easy rhythm of people who had survived enough to appreciate calm.

The knock was firm. Not urgent. Not aggressive. Just firm, the kind of knock that suggested the person on the other side believed they had a right to be there even if they were nervous about it.

Thomas opened the door expecting a neighbor.

Instead, a man in his forties stood on the porch, coat buttoned against the cold, hair damp with winter air. He held himself stiffly, as if bracing for impact. His eyes were an unsettling gray-blue that hit Thomas like a memory he couldn’t place.

For a second, neither of them spoke. The cold breathed between them.

Then the man swallowed and asked, carefully, “Did you serve in Germany in 1945?”

Thomas felt his chest tighten, not in fear exactly, but in the sudden sensation of a door in his mind being forced open.

“Yes,” Thomas said, and his voice sounded older than he expected.

The man exhaled as if he had been holding his breath for years. “My name is Michael,” he said. “Michael Adler. I’ve been trying to find you for a long time.”

Thomas’s hand stayed on the doorknob. He didn’t invite the man in. He didn’t shut the door either. He stood in the threshold like it was a border, like stepping fully into this conversation might mean stepping into a world he had spent decades trying to keep behind him.

“I don’t understand,” Thomas said carefully.

Michael’s mouth tightened. He looked at Thomas with an expression that was a mixture of apology and determination. “I’m not here to accuse you,” he said quickly, as if he had rehearsed that line. “I’m not here to cause trouble. I just… I have questions.”

Behind Thomas, the house made small, ordinary sounds. The refrigerator clicked. The faucet dripped once. Somewhere a clock ticked. Anna was in the kitchen, he knew, and in another moment she would probably appear with a dish towel in her hands, her face calm, her eyes sharp.

Thomas lowered his voice without meaning to. “About what?” he asked.

Michael’s gaze flicked past him into the hallway, and his eyes caught on a framed photograph on the wall. Thomas in uniform, younger, face sharper. Anna beside him, hair pinned back, expression composed even in the photograph.

Michael’s throat moved. “About her,” he said softly.

Thomas’s stomach dropped.

“How do you know my wife?” Thomas asked, and the question came out rougher than he intended.

Michael’s hands trembled slightly. He shoved them into his coat pockets like he was ashamed. “I don’t,” he said. “Not really. I know her name. Or I did. I know what it used to be.”

Thomas felt the past shift in the air, as if it had been waiting for this moment.

“Come in,” Thomas said finally, because keeping him on the porch felt like cruelty, and whatever this was, it was already inside the house whether Thomas liked it or not.

Michael stepped inside carefully, as if entering a museum. He removed his hat. His hands were pale from the cold. He looked around as if trying to anchor himself in details. The smell of lemon polish. The rack of shoes. The small American flag in a vase by the door, a childish thing one of the grandchildren had brought home from school.

Thomas led him into the living room. Winter light spilled across the carpet. A baseball glove lay on a chair. A knitted blanket Anna had made was folded over the back of the couch.

Michael sat on the edge of the sofa as if he didn’t deserve comfort. Thomas remained standing.

“Tell me,” Thomas said, because war had taught him that sometimes you survived by getting to the point.

Michael nodded. He reached into his bag and pulled out a folder. Paperwork. Thomas felt a bitter flicker of irony. Wars began with speeches, but lives were altered by forms.

Michael slid a document across the coffee table. Typed lines. Stamps. Dates.

Thomas didn’t read it yet. He stared at the paper as if it might bite.

“I was born in June of 1945,” Michael said. “Near Hannover. My earliest records are incomplete. A lot of them are incomplete. The war was ending, offices were burning, people were moving, and names got crossed out or changed.”

Thomas’s pulse thudded in his throat.

Michael continued, careful, as if he had learned that too much emotion could make people shut down. “I was placed in temporary care. Then I was moved. Then I was adopted by an American family who emigrated back. I grew up in Ohio. They were good people. They loved me. But I always knew something didn’t fit. There were gaps. A woman listed as translator. A name partially erased. A note about someone marrying a British soldier.”

Thomas’s hand tightened on the back of the chair. Ohio. America. The world looping back on itself.

Michael’s voice softened. “I started searching when I was old enough. It took years. Archives. Letters. Requests. Waiting. I found a name I wasn’t supposed to find.” He swallowed. “Anna Krüger.”

Anna’s footsteps sounded in the hallway.

She entered carrying a tray with tea, moving with the quiet efficiency that had never left her. She stopped when she saw the stranger. Her eyes went to Thomas first, reading his face. Then they went to Michael.

For a long moment, nobody spoke.

Anna’s face did not collapse into drama. It did not twist into shock. It went still, the way it had gone still in 1945 in that ruined hallway, the way it went still when she chose control because control was survival.

Michael stood slowly, as if standing might make the moment easier to carry. His eyes shone. He looked like a man holding himself together by sheer will.

“Anna,” he said, and his voice cracked on her name.

Anna’s fingers tightened around the tray. The cups clinked softly. She set the tray down with deliberate care, as if if she moved too quickly, something would shatter.

“You found me,” she said.

It wasn’t a question. It was a statement, heavy with everything it implied.

Michael nodded, blinking hard. “I didn’t come to hurt you,” he said quickly. “I didn’t come for money or anything like that. I just wanted to know the truth. I wanted to know who I am.”

Anna glanced at Thomas, and in that glance Thomas saw something he had never seen from her, not fear of punishment, but fear of changing the shape of their life with one sentence.

Thomas couldn’t speak. His mind raced through decades of overlooked details. Letters never sent. Dates that made her quiet. Names avoided like landmines.

Anna sat down slowly in the armchair opposite the sofa, posture upright, hands folded in her lap like a woman about to answer a question she had been dodging for forty years.

“Yes,” she said quietly. “It is true.”

Thomas felt something inside him go cold.

Michael’s eyes closed for a second, relief and grief colliding. When he opened them, he looked at Anna with longing and restraint, as if he didn’t know whether he was allowed to want anything from her.

Anna did not begin with excuses. She did not say forgive me. She did not dramatize. She simply spoke in the same calm voice Thomas had first heard in that ruined building.

“In the last months,” she said, “everything was chaos. People were hungry. Men with guns changed uniforms and called themselves different names. Women survived as they could.”

Her voice wavered on the word survived, then steadied again.

“I was working as translator because it kept me fed,” she continued. “It kept my mother fed. My father was gone. My brothers were gone. Everyone was gone. I had one thing, my languages, and that made me useful. Useful meant alive.”

Michael’s breath caught. “And me?” he asked, voice small now.

Anna looked at him, and her composure softened not into sentimentality, but into something raw and honest.

“You were born in June,” she said. “I remember the day. It rained. The roof leaked. The woman who helped me had hands like iron.”

She swallowed. “I did not have milk,” she said. “I did not have blankets. I did not have anything. There were rumors about what would happen to women with babies. There were officials who moved people. There were men who took what they wanted and called it order.”

Thomas felt his chest tighten, the old fury at helplessness rising, but he stayed silent, because this was Anna’s truth, not his.

Anna’s voice lowered. “There was a convent outside the city,” she said. “They were taking children. Not always safely. Not always kindly. But they kept lists. They wrote names. They tried.”

Her hands tightened in her lap. “I left you there.”

The words landed without drama, which made them heavier. Thomas gripped the chair harder, feeling the room tilt, feeling his entire understanding of his marriage shift like furniture sliding on a ship.

Michael’s face crumpled, then steadied. He nodded once, as if he had always known the truth would not be clean.

“I did not leave you because I did not want you,” Anna said, voice firm now, as if she needed him to hear that without distortion. “I left you because I could not keep you alive. I left you because I believed if your name was written, if someone had put you on a list, there would be a chance you would not disappear.”

Michael’s voice trembled. “Did you write my name?”

Anna’s lips trembled too. “I wrote what I could,” she said. “I wrote enough.”

Thomas flinched at the word enough. Enough information for a child to have a trail. Not enough information for the wrong person to find him first. The kind of calculation no one should ever have to make.

Michael stared at the folder, then at Anna. “Did you try to find me?” he asked.

Anna’s gaze drifted to the window, to the winter branches outside. For a moment, Thomas could almost see the decades in her eyes.

“Yes,” she said. “At first. I wrote. The letter came back. The building was gone. I asked offices. They told me records were incomplete. Then I came to England. Then I met your husband.” She looked at Thomas. “And I told myself you were safe. You were alive. That was the point. That was what I chose.”

Thomas finally found his voice, and it came out rough. “Why didn’t you tell me?” he asked.

Anna closed her eyes briefly, then opened them. She looked older suddenly, not from age, but from the release of carrying something alone.

“Because you loved me,” she said simply. “And I was afraid you would stop.”

The sentence hit Thomas harder than any accusation could have. Stillness filled the room, thick and absolute. He had expected, if the past ever returned, that it would arrive with scandal or betrayal. Instead it arrived as sacrifice, as a decision made in a leaking room in 1945, and carried like a stone for forty years.

Michael’s shoulders shook once, and he pressed his lips together hard, fighting tears like a man who had spent his life trying not to take up space in other people’s stories.

“I grew up loved,” he said hoarsely, as if offering comfort the only way he knew. “I did. I had a home. They were good people. But I always felt like I was missing a page.”

Anna nodded once, accepting that pain without trying to fix it. “I am sorry,” she said, and the apology was quiet, not performative. “I am sorry you carried that.”

Thomas stared at Anna and realized he didn’t feel anger. Not at her. What he felt first was a slow, heavy understanding that made his throat tighten. He saw her not as the woman who made tea and folded laundry and built a quiet life, but as a young woman in a shattered country making an impossible choice with no guarantee she would even live long enough to regret it.

Michael’s voice was gentler now. “I don’t want to destroy your life,” he said. “I know you built something. I can see it. I’m not here to take her away. I’m not here to make her suffer. I just needed the door to open.”

Anna’s hands unclasped, then clasped again, a small betrayal of nerves. “Then it is open,” she said.

Thomas sat down slowly, as if his legs had remembered their age. He looked at Michael, at the man who was somehow both stranger and connection, and he realized there was no script for this. War had taught him how to follow orders and survive chaos. It had not taught him how to share a living room with the consequence of a choice made decades ago.

“What do you want from us?” Thomas asked finally, not harshly, but honestly.

Michael’s eyes widened, and he shook his head quickly. “Nothing,” he said. “I mean, I don’t want money. I don’t want to take her away. I don’t want to punish anyone. I just…” He swallowed hard. “I want to know where I came from. I want to know why. I want to know if I was loved.”

Anna’s breath caught at the last question. For a moment, her composure threatened to crack entirely, and Thomas saw how close the truth had lived under her skin all these years.

“Yes,” Anna said, and her voice shook once, a single tremor she did not try to hide. “You were loved. You were loved so much I did the only thing I could to keep you alive.”

Michael covered his mouth with his hand, and his eyes flooded. He didn’t sob. He didn’t collapse. He simply sat there and let the tears fall, as if he had been holding them back for forty years too.

Thomas found himself standing, walking to the kitchen without thinking, because movement kept him from drowning. He filled the kettle, turned on the stove, stared at the flame as if it could explain something.

Anna appeared in the doorway a minute later, quiet, her face pale. She watched Thomas with eyes that asked a question she couldn’t say out loud.

Are you leaving me?

Thomas turned and saw it, and something in him softened and hardened at the same time.

“I’m not going anywhere,” he said quietly.

Anna’s shoulders sagged a fraction, a release so small it would have been invisible to anyone else.

They returned to the living room with tea because tea was what people did when life was too large. Thomas set cups down with hands that were steadier than he felt. Michael wiped his face, embarrassed.

“I’m sorry,” Michael murmured.

“Don’t be,” Thomas said, and surprised himself with the firmness in his voice. “You didn’t do anything wrong.”

Michael nodded, staring into his cup like it held answers. “My adoptive parents,” he said, voice calmer now, “they didn’t know everything either. They weren’t hiding. They just didn’t have the records. I started looking after my adoptive mother died. My father encouraged it. He said it was okay to want to know. But there were times he looked… scared.” Michael’s mouth tightened. “Like he thought I’d disappear if I found the truth.”

Anna’s gaze softened, and for a moment she looked less like a woman defending a secret and more like a woman recognizing another family’s fear.

“People think love is possession,” Anna said quietly. “It is not. Love is sometimes letting go.”

Michael nodded slowly, absorbing that as if it were new language.

Thomas sat back and forced his breathing to slow. He listened, not just to the words, but to the tone, the pauses, the careful way Michael tried not to demand anything. Thomas understood that kind of restraint. It was the restraint of someone who had spent his life feeling like an extra guest in his own story.

“I have more,” Michael said after a while, tapping the folder. “Documents. Some notes from a Red Cross archive. A reference to a list from a convent. I don’t know if it’s the same one. I can’t prove everything. But I can prove enough.”

Anna stared at the folder as if the paper itself offended her. “Paper survives,” she said again, and there was a thin edge to it now. “Sometimes it is the only thing that does.”

Thomas reached for the top page and finally forced himself to read.

Names. Dates. Stamps. A line that made his throat close, because it confirmed what his heart already knew. A child born June 1945. Mother: unknown, translator listed, surname partially obscured. Placement: convent care. Transfer. Adoption.

Truth flattened into ink.

Thomas put the paper down and stared at the coffee table as if it might crack.

All at once he remembered Anna’s hands in their early years, always smoothing, always organizing, always controlling. He remembered the way she went quiet every June, the way she would stand at the window for too long and then turn away quickly when he entered the room. He remembered a moment in 1958 when Margaret, still small, had found a folded letter in a drawer and asked what it was. Anna had taken it gently, smiling, saying, “Just old writing,” and Thomas had accepted that without question.

He felt guilt rise like bile, not because he had been wrong to trust her, but because he had been so eager for peace that he had never looked closely at what it cost her.

Michael sat very still, as if waiting to be dismissed. Thomas saw that too, the way his body held itself like it expected rejection.

Thomas exhaled slowly. “How did you find us?” he asked.

Michael let out a shaky laugh that held no humor. “It took years,” he said. “There were archives in Germany, some in Britain. I wrote letters to offices I wasn’t even sure still existed. I waited months for replies. Sometimes nothing came. Sometimes someone answered and told me they couldn’t help. Sometimes someone helped quietly. There was a librarian in Hanover who told me where to look next. There was an old woman at a church who recognized the name and said, ‘She left.’”

Michael looked down at his hands. “Then I found a mention of a British soldier. Thomas Ward. It was almost too common. I looked through registry lists. I found one marriage record. A war bride. I found a shipping record. Then I found a census. Then I found your daughter’s wedding announcement in a local paper because it mentioned her moving to Massachusetts.” He lifted his eyes to Thomas. “From there, it was… human work. Asking. Searching. Hoping I didn’t destroy something by showing up.”

Anna closed her eyes briefly at the word destroy.

Thomas leaned forward, his elbows on his knees. “You didn’t destroy it,” he said quietly. “You revealed it.”

Anna opened her eyes again. Her gaze went to Thomas with something like pain in it, but also something like relief, because the truth, once spoken, did not have to be guarded anymore.

Michael swallowed. “Can I ask…” He hesitated, then forced himself. “Do you hate her?”

Thomas’s head snapped up.

Anna’s breath caught.

Thomas stared at Michael, at the earnest fear behind the question, and he understood that Michael’s life had been shaped by gaps and what-ifs and the terror that someone’s love for him might be conditional.

“No,” Thomas said, firm. “I don’t hate her.”

Anna’s eyes filled, but she did not cry. If she had cried, she would have cried in the kitchen alone decades ago. What remained now was steadiness and a vulnerability she could no longer hide.

Michael nodded, and a tension in him eased, as if he had needed that answer more than he’d admitted.

They sat like that for a long time, the three of them suspended in a quiet that was not the old quiet of denial, but a new quiet of recalibration. Outside, the neighborhood carried on. Somewhere a dog barked. Somewhere a car door slammed. Somewhere a child laughed, the sound bright and careless.

Eventually, Michael spoke again, careful. “I don’t know what I’m asking for,” he admitted. “I don’t know what is fair. I don’t want to be selfish. But… I’d like to know you. If that’s possible. Not as a replacement for my parents. I don’t want to erase anyone. I just want to stop feeling like a question mark.”

Anna’s throat worked. “You are not a question,” she said, and her voice was soft but certain. “You are a life.”

Thomas watched her, and something in him shifted again. He realized Anna had spent decades turning herself into a person who could survive, who could be a wife, a mother, a neighbor, a citizen. She had done that without allowing one part of her past to enter the picture. Now, with Michael in front of her, she had to be all of herself at once, and it looked exhausting.

Thomas stood up, walked to the window, stared out at the thin winter light. He thought of the girl Anna had been in 1945. He thought of the woman she became in England, learning to swallow words like they were medicine. He thought of the mother she had been to Peter and Margaret, careful and steady. He thought of how easy it was to call someone loyal when you didn’t see what they were carrying.

When he turned back, he found Michael watching him with the wary patience of someone used to waiting for permission.

“We can try,” Thomas said, and heard his own voice sound foreign with the weight of it. “We can try to… find a way. But it won’t be quick. And it won’t be simple.”

Michael’s eyes shone again. He nodded once, fiercely, as if he would accept any terms as long as he wasn’t shut out.

Anna’s shoulders rose and fell with a slow breath. “If you are here,” she said to Michael, “then you must also hear something else.”

Michael leaned forward, attentive.

Anna’s gaze dropped to her hands. “When I left you,” she said, “I did not leave you with a hope that I would find you later. I left you with a hope that you would live. That was all I allowed myself to want, because wanting more would have killed me.”

Michael’s face tightened. “I understand,” he whispered, though his voice suggested understanding hurt.

Anna lifted her eyes. “And when I came to England,” she continued, “I did not tell Thomas because I was afraid. Not only of losing him. I was afraid of what it would make me. In those years, a woman’s choices were not judged kindly. People wanted clean stories. They did not want war stories. They wanted heroes and villains. I was neither. I was just… trying.”

Thomas felt the sting of that, because he understood how easily the world had demanded simplicity from people who had none to give.

Michael swallowed. “I’m not here to judge you,” he said quickly. “I’m not.”

Anna nodded. “Good,” she said, and the firmness in her voice returned for a moment. “Because you do not have the right to judge a girl in a war.”

The sentence hung heavy and true.

Michael bowed his head slightly, accepting the boundary.

Thomas sat again, feeling his joints ache, feeling his age, feeling the decades compressing into this room.

They talked until the light began to fade, and the conversation moved in careful arcs. Not dramatic confessions, not melodrama. Simple facts. A name of a city. A memory of a smell. A year. A school.

Michael told them about Ohio, about growing up in a small town where everyone knew everyone, about being the child people called “special” without knowing what they meant. He told them about his adoptive father, Harold Adler, a quiet man who had served in Korea and believed in showing up for people rather than talking about it. He told them about his adoptive mother, Ruth, who baked bread every Sunday and insisted Michael learn how to fix things with his hands.

Anna listened with an expression that was both pain and gratitude, as if each detail both soothed and cut. Thomas realized she was hearing, for the first time, what her decision had actually produced. Not just survival, but a life with texture.

Michael asked about Germany, but gently, and Anna gave him only what she could. She spoke of rubble, of hunger, of the strange silence after bombings when the world felt stunned. She did not speak of violence directly, but Thomas heard it in the way her voice tightened around certain phrases, the way she glanced at the window as if checking that the past wasn’t standing outside listening.

As the afternoon became evening, Anna stood and began setting plates for dinner automatically, because she did not know how to keep her hands still. Thomas watched her move through the kitchen, watched the familiar motions, and felt an ache in his chest that was not anger, not betrayal, but grief for what she had carried alone.

Michael hesitated at the edge of the doorway. “I should go,” he said, as if leaving before he was asked was safer.

Anna turned, dish towel in her hands, and for a second she looked like she might break. Instead she said, quietly, “You can stay for dinner.”

Michael’s eyes widened. “Are you sure?”

Thomas answered before Anna could second-guess herself. “Stay,” he said simply.

They ate at the kitchen table where Thomas had read the newspaper hours earlier, the ordinary scene made strange by the presence of a man who belonged to a part of Anna’s life Thomas had never seen. They ate roast chicken and potatoes, the kind of meal Anna made without thinking, and the warmth of it felt almost like a defiance against everything cold and unfinished.

Michael ate carefully, as if afraid to take too much. Thomas noticed that and felt a stab of recognition. Some habits didn’t come from war alone. They came from living a life where you didn’t feel entitled to space.

After dinner, Michael stood by the door again, coat in hand, and looked at Anna like he was memorizing her face.

“I don’t know how to do this,” he said softly.

Anna’s mouth tightened. “Neither do I,” she admitted.

Michael nodded. “Can I… can I call? Or write? Or something?” His voice cracked on the last word.

Anna’s eyes flicked to Thomas, and Thomas gave a small nod, because he understood that this was not just Anna’s decision anymore. Their marriage was not a private island. It had always been built in a world full of history. Now history was knocking from inside.

“Yes,” Anna said. “You can call.”

Michael exhaled shakily. “Thank you,” he whispered, and the gratitude sounded like it was built on years of wanting.

When the door closed behind him, the house felt different. Not empty, not quiet, but altered, like someone had moved furniture in the dark and the familiar shapes were now unfamiliar.

Anna stood at the sink, staring at the dishes without washing them.

Thomas watched her for a long moment, then walked up behind her and placed his hand gently on her shoulder. He expected her to flinch. She didn’t.

“I didn’t know,” he said quietly.

Anna’s shoulders rose and fell with a slow breath. “I know,” she replied.

Thomas swallowed. “I wish you had told me.”

Anna’s laugh was small and bitter, with no humor in it. “So do I,” she said. “But wishing does not change who we were.”

Thomas turned her gently so she faced him. Her eyes were wet now, the composure finally giving way to the simple truth that carrying something alone eventually carves hollows in you.

“Were you afraid of me?” Thomas asked.

Anna stared at him, as if the question itself was painful. “No,” she said. “I was afraid of the world. I was afraid of what people would call me. I was afraid of what it would do to you, to our children, to our life. I was afraid of the story.”

Thomas’s throat tightened. “And what about you?” he asked. “What did it do to you?”

Anna blinked slowly, and for the first time, she looked like she might admit it out loud. “It did not let me sleep,” she said simply. “Not fully. Not ever.”

Thomas felt tears sting his eyes, and he hated them, because he had never liked tears, not his own. Tears felt like helplessness.

“I’m here,” he said, and the words sounded inadequate.

Anna nodded once. “I know,” she whispered. “That is why I married you. Because you were here. You stayed.”

Thomas’s hand tightened on hers. “Then we will stay now too,” he said, and surprised himself with the steadiness of it.

Over the next days, the story unfolded in layers, not as a sudden explosion but as a slow release. Anna began to share pieces she had never spoken aloud. Not everything. Not in full detail. But enough that Thomas began to see the outline of the girl she had been.

She told him about her mother, who had lived through shortages with a stern practicality, who taught Anna to mend socks and keep books and never trust someone who smiled too much. She told him about the day a neighbor disappeared, and everyone pretended not to notice. She told him about standing in line for bread with a baby in her belly, the fear clawing at her ribs because she didn’t know how to bring a child into a world that had no mercy.

She told him about the convent, about the women who ran it, exhausted but determined, about the way they kept lists like lists were prayers.

“They were not saints,” Anna said one night, sitting at the kitchen table with the lights low. “They were just women. They were scared too. But they wrote names anyway. They did not let children become air.”

Thomas listened, feeling a tightness in his chest he could not name. He realized he had always imagined Anna’s past as a vague fog of war. Now he saw it as a series of rooms, choices, days, human faces.

Michael called, then came again, cautious each time, like a man approaching a fire he both needed and feared. He never showed up unannounced again. He asked permission with every step, as if he believed one wrong move would make the door slam forever.

The first time Margaret learned the truth was not in a dramatic family gathering. It happened on an ordinary Tuesday when she came by with groceries and found Michael sitting at the table with Thomas, talking quietly about a book Harold Adler had loved.

Margaret froze in the doorway, grocery bags slipping in her hands.

Thomas stood quickly. “Maggie,” he said, using the old nickname, the one that softened her adult edges. “Come sit.”

Margaret’s eyes darted to Michael, then to Anna, who stood by the counter like a woman bracing herself.

“Who is this?” Margaret asked, voice tight.

Michael stood, awkward, respectful. “I’m Michael,” he said softly. “I believe I’m…” He swallowed. “I believe I’m Anna’s son.”

The bags hit the floor with a dull thud, spilling oranges across the kitchen tiles. One rolled under the table. Another bumped gently against Thomas’s shoe.

Margaret stared at her mother as if waiting for denial.

Anna did not deny it.

Margaret’s face crumpled, not in anger first, but in shock, the kind that makes you feel suddenly young and unsteady. “You never told me,” she whispered.

Anna’s eyes filled. “I could not,” she said.

Margaret’s voice rose, not loud, but sharp with pain. “Why? Why not? I’m your daughter.”

Anna’s breath shook. “Because I was afraid,” she said, and then, quieter, “Because I wanted you to have a mother who was not… divided.”

Margaret pressed her fingers to her mouth, tears spilling. “And what about him?” she choked out. “What about his life?”

Michael’s voice was gentle. “I had a life,” he said. “I did. I was loved. I’m not here to accuse anyone. I just wanted to know.”

Margaret’s gaze snapped to him, and something in her expression softened, because she heard the restraint, the care.

Thomas stepped forward and quietly began picking up oranges, because it gave his hands something to do and because he didn’t want Margaret’s pain to turn into a scene that would wound everyone.

They sat. They talked. They cried some, but not in the dramatic way stories imagine. In the simple way grief leaks out when it has been held too long. Margaret asked questions, sometimes sharply, sometimes softly, and Anna answered what she could. When Anna couldn’t answer, she said, “I don’t know how,” and Thomas realized that was the most honest sentence in the house.

Daniel arrived later, called by Margaret, and walked into a room full of quiet tension. Daniel’s American confidence faltered for the first time Thomas could remember. He looked from face to face, gauging.

Margaret told him in a voice that sounded like it belonged to someone else. Daniel sat down, listened, and then, because he was Daniel, he did the simplest thing. He said, “Okay,” in a voice that meant, I’m not going to make this harder.

Later that night, when everyone left, Thomas sat with Anna on the couch, the house dim, the American flag in the vase still standing bright and innocent.

“Do you regret it?” Thomas asked her quietly.

Anna stared at the far wall for a long time. “I regret the world that made it necessary,” she said finally. “I regret the pain.” She swallowed. “I do not regret that he lived.”

Thomas nodded, and felt his throat tighten again.

Weeks became months, and the family adjusted in awkward, imperfect ways. Michael became a presence, not a replacement. He didn’t ask to be called son. He didn’t demand photographs. He didn’t claim space like a conquering truth. He showed up carefully, brought small gifts, asked about Thomas’s garden, asked about Anna’s recipes, asked about Margaret’s children with a quiet curiosity that was more longing than entitlement.

Thomas began to notice how much Michael resembled Anna in the smallest ways. The way he held his cup. The way he listened without interrupting. The way he chose words carefully, as if words could be dangerous if thrown too fast.

One afternoon in early summer, Michael arrived carrying a small paper bag from a bakery. He set it on the table and said, “I brought bread,” and the simple sentence made Anna’s hands freeze for a fraction of a second.

Thomas watched her, understanding now that certain gestures were not just gestures. Bread was not just bread. Bread was war. Bread was survival. Bread was the line between dignity and desperation.

Anna forced her hands to move, took the bag, set it down carefully. “Thank you,” she said.

Michael glanced at her, as if sensing the weight he didn’t fully understand. “It’s just…” He hesitated, then smiled faintly. “My adoptive mother used to bake. It always made the house feel safe.”

Anna’s eyes softened, and she nodded once. “Yes,” she said. “Safe.”

Thomas realized then that the past was not only pain. It was also small bridges being built, quietly, in kitchens, over tea and bread and careful words.

One day, Michael brought a small box and set it in front of Anna. “I don’t want to overwhelm you,” he said quickly. “You don’t have to look. But I thought you might want to see.”

Anna stared at the box like it might explode.

Thomas sat beside her, his hand close to hers but not touching until she reached.

Anna opened the box slowly. Inside were photographs. Not of 1945, but of a childhood in Ohio. A boy on a bicycle. A boy holding a fish. A boy in a school play, smiling too wide. A graduation photo. A wedding photo with a woman named Elaine, Michael’s wife, and two small children.

Anna’s breath caught. She touched the edge of one photograph with a finger as if afraid to smudge it.

Michael’s voice shook. “I didn’t have a terrible life,” he said, almost pleading. “I don’t want you to think you ruined me. You didn’t.”

Anna’s tears finally fell then, not dramatic, just quiet, sliding down her cheeks as she stared at a picture of a life she had saved but never witnessed.

“I did not ruin you,” she whispered, and the words sounded like she was convincing herself.

Thomas sat with her as she cried, his arm around her shoulders, feeling the strange ache of realizing that love was not just the life you built. Love was also the rooms in your partner you never entered because you didn’t know the door existed.

Summer came, and with it, the date Anna had always carried like a stone. For decades, Thomas had noticed she grew quieter around early June, but he had never known why. Now, as June approached, he watched her move through the days with a tension he could finally name.

One evening, Thomas found her in the garden after sunset, standing by the tomato plants, hands clasped, staring at the soil.

“It’s close,” Thomas said quietly.

Anna nodded. “Yes,” she whispered.

Thomas stepped beside her. “Do you want to do something?” he asked. “Mark it? Acknowledge it?”

Anna’s mouth tightened. “I do not know how to honor a day that hurt,” she said.

Thomas looked at the dark garden, then at the house behind them, the windows glowing with warm light. “We can just be awake,” he said. “We can be here. That can be enough.”

Anna stared at him, and something in her face softened. “You always try to make it simple,” she said.

Thomas’s smile was faint. “Sometimes simple is all I have,” he replied.

That night, they sat at the kitchen table with the lights low and told stories. Thomas told Anna something he had never told her, about a night in 1944 when he had been sure he would die and had whispered his mother’s name into the dark like it was a charm. Anna listened, and in return she told him about the day she decided to leave Michael at the convent, the way her hands shook so badly she couldn’t tie the blanket properly, the way she kissed his forehead and then turned away because if she looked at him again she knew she would stay and staying would kill them both.

Thomas did not interrupt. He did not try to fix. He simply listened, because he finally understood that some truths didn’t need solutions. They needed witness.

In late summer, Michael asked if Anna would go with him to Germany.

The request landed like a thunderclap even though he said it gently.

“You don’t have to,” Michael added quickly. “I’m not asking to drag you back into anything. But I want to see where I was born. I want to stand in the place. And… I thought maybe you might want to see it too. Or maybe you wouldn’t. I don’t know.”

Anna went still.

Thomas watched her face, the way old walls rose instinctively.

“No,” Anna said quickly, then swallowed. “I mean… I don’t know.”

Michael nodded, accepting the uncertainty. “We don’t have to decide now,” he said softly.

After Michael left, Thomas found Anna sitting in the living room, staring at nothing.

“You don’t have to go,” Thomas said, and meant it. He didn’t want to push her into pain for the sake of a neat ending.

Anna’s voice was quiet. “I have spent my life not going,” she said. “Not going back. Not going into that room. Not touching that memory. Perhaps… perhaps that is also a kind of prison.”

Thomas felt his throat tighten. “If you go,” he said gently, “we go together. Not because you need guarding, but because you shouldn’t be alone.”

Anna looked at him, and there was gratitude in her eyes, and fear.

They decided to go in the fall, when the leaves in Massachusetts turned red and gold again, as if time loved repeating itself. Margaret worried, of course. Daniel offered to help with tickets. Michael’s wife Elaine called Anna and spoke carefully, respectfully, like a woman trying not to intrude on sacred ground.

“You don’t owe us anything,” Elaine said over the phone. “I just want you to know we’ll support whatever you decide. And thank you for… for letting Michael have this.”

Anna’s voice was quiet. “He has it because he lived,” she replied.

The flight to Germany was long, and Thomas found himself staring out the airplane window at clouds that looked too peaceful to be real. He held Anna’s hand, feeling her grip tighten during takeoff like the world itself might drop.

Michael sat across the aisle, looking out with eyes that seemed both eager and terrified.

When they landed, the airport felt modern, clean, full of bright signs and people moving with ordinary impatience. Thomas felt disoriented, as if he had expected the past to be waiting at the gate wearing old clothes.

Anna moved through customs with a composure that looked almost cold, but Thomas could feel the tension in her wrist under his fingers.

They drove toward Hannover, and the countryside rolled past in green and gold, fields and villages that looked nothing like the rubble Thomas remembered. Michael stared out the window, his mouth slightly open, as if trying to match the landscape to his internal map of questions.

“Do you recognize anything?” Michael asked Anna softly.

Anna’s gaze stayed forward. “No,” she said. “That is the strange thing. War makes a world, then peace makes a different one. But the body remembers.”

Michael swallowed, and for once he didn’t ask more.

They found the convent with the help of archives and a local historian Michael had contacted months earlier. It stood outside the city, quiet, surrounded by trees. It looked smaller than Thomas had imagined. Not a dramatic fortress of fate, just an old building with worn stone and a small garden.

A nun, older now, greeted them politely. Not the same woman who had been there in 1945, of course. But the same kind of calm, the same kind of measured words.

“We have records,” the nun said in German, and Anna translated automatically even though the nun’s English was good. Translation was a reflex for Anna, a way of controlling what entered the room.

They sat at a wooden table, and a folder was placed in front of them. Thomas watched Anna’s hands hover over it like she was afraid to touch paper that held her past.

Michael’s fingers trembled when he reached for the top page.

Thomas read the familiar language of stamps and dates, but the content was different here. More precise. The entry of a child received. The note of a young woman, translator, desperate. The line that made Anna inhale sharply: Mother’s signature. A name. Anna Krüger, written in careful script.

Anna stared at her own handwriting as if it belonged to someone else.

“I wrote it,” she whispered.

Michael swallowed hard. “You did,” he said softly, as if confirming her reality.

Anna’s eyes filled again, and Thomas felt his own throat tighten. There was something brutal about seeing evidence of a choice you’ve carried in silence. Evidence made it real in a way memory could not soften.

Outside, the garden was quiet. A bird chirped. Life went on, careless.

Michael stood and walked to the small chapel, his steps slow. He sat in a wooden pew and stared at the altar without praying. He simply sat, as if the act of being there was the prayer.

Anna remained at the table, frozen.

Thomas touched her hand. “It’s all right,” he whispered, not because it was, but because she needed something steady.

Anna’s voice shook. “I thought… I thought if I never saw it again, it would stay in the past,” she said.

Thomas nodded. “But it was always in you,” he replied.

Anna’s shoulders sagged slightly, as if surrendering to that truth.

Afterward, they walked outside into the garden. Michael stood near a stone wall, staring at a patch of earth, and Thomas realized he was trying to imagine a baby being carried across that ground.

Michael turned to Anna, and his voice was quiet. “Did you hold me here?” he asked.

Anna’s mouth tightened. “Yes,” she whispered. “For a little while.”

Michael nodded slowly, tears shining but not falling. He looked at Thomas then, as if suddenly remembering that this man had been part of Anna’s life for decades.

“I’m sorry,” Michael said awkwardly. “I didn’t mean to… disrupt.”

Thomas studied him, this grown man who had arrived with a folder and a question mark, and felt something in his chest loosen.

“You didn’t disrupt,” Thomas said. “You completed.”

Michael’s brows knit. “Completed what?”

Thomas exhaled. “A story doesn’t stop just because we stop talking about it,” he said quietly. “It keeps moving. You’re part of it. That’s all.”

Anna listened, and a small sound escaped her, halfway between a laugh and a sob. “Thomas always makes everything sound like a sentence,” she murmured.

Thomas’s mouth twitched. “I’ve had practice,” he said.

They returned to Massachusetts changed in quiet ways. Not magically healed. Not suddenly whole. But altered.

Anna began to sleep, a little. Not perfectly, but she stopped waking every night at the same hour. She began to speak more, small pieces of her past leaking into conversation like sunlight creeping under a door.

Michael became a regular presence, and the family adjusted. Margaret’s children, old enough to understand something but not everything, asked innocent questions that made adults freeze.

“Is Michael Grandma’s kid?” the youngest asked once, mouth full of cereal.

Margaret choked on her coffee.

Michael laughed softly, more amused than offended. “Yes,” he said gently. “I’m her son.”

The child blinked. “Okay,” he said, and went back to cereal, because children have a way of accepting what adults make complicated.

That simple acceptance did something to the room. It eased a tightness none of them had admitted was there.

As months went on, Thomas watched Anna and Michael build something cautious and fragile. Not a fantasy of instant mother and son. Something more real. Conversations about ordinary things. The weather. Food. Books. The way Michael’s son liked baseball. The way Anna never liked baseball but attended games anyway because showing up was love.

One afternoon, Michael arrived with a small framed photo. It was a picture of Ruth Adler, his adoptive mother, smiling in a kitchen with flour on her hands. Michael set it on the table near Anna.

“I want you to know her,” Michael said softly. “In some way. She was part of my life. I don’t want you to feel like she’s being erased.”

Anna stared at the photo for a long moment. Then she reached out and touched the frame gently.

“She looks kind,” Anna whispered.

“She was,” Michael said.

Anna swallowed. “Then I am grateful,” she said, and the sentence sounded like a door opening to a bigger kind of truth. It wasn’t just that Michael had lived. He had lived well, with love. That was a miracle Anna had not allowed herself to imagine.

Thomas found himself watching Michael sometimes with a strange tenderness. He had expected resentment. He had expected jealousy. He had expected the past to accuse him of stealing years that belonged to someone else.

Instead, what he felt was a quiet responsibility. Not as a replacement father, not as an owner. Simply as a witness to the complicated shape love could take.

One evening, months after the knock, Thomas sat on the porch with Michael, the air cool and clean. The neighborhood was quiet. Porch lights glowed like small promises. Somewhere a distant radio played softly.

Michael stared at the street for a long time, then said, almost embarrassed, “I used to imagine my biological father was a soldier. I don’t know why. It just made sense in my head. Like the war created me and then forgot me.”

Thomas’s chest tightened. “Do you know who he was?” he asked carefully.

Michael shook his head. “No,” he said. “The records don’t say. The convent didn’t know. Anna…” He hesitated. “She didn’t tell me. I don’t think she wants to. I don’t know if she can.”

Thomas nodded. He understood that too. Some truths were not just secrets. They were landmines.

Michael’s voice softened. “I don’t need a name to know I existed,” he said. “I just…” He exhaled. “Sometimes I wonder if he knew.”

Thomas stared out at the street, at the quiet American normalcy, and felt the weight of the question.

“I don’t know,” Thomas said honestly. “But I know this. You are here. You didn’t need his knowing to be real.”

Michael’s eyes shone, and he nodded once, swallowing.

Inside the house, Anna was laughing softly at something Margaret’s child said. The sound was small, but it was different than the laughter of years past. Offerings. Those were the moments Thomas noticed most. Not the dramatic confrontations people imagined, but the small shifts where life became a little less guarded.

Later that night, Thomas found Anna in the kitchen, standing by the sink, staring at nothing again. He approached quietly, because sudden presence still startled her sometimes.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

Anna nodded, but her eyes were distant. “I keep thinking,” she said softly, “how close I was to never being found. How close he was to never knowing. How close we were to living our whole lives with this hidden, like a stone in a pocket.”

Thomas leaned against the counter beside her. “And now?” he asked.

Anna turned her head slightly. “Now the stone is on the table,” she said. “We can see it. It is heavy, yes. But it is not inside me alone.”

Thomas reached for her hand, and this time she squeezed back without hesitation.

“Love,” Anna said quietly, as if tasting the word. “I thought love was what I did to protect you. To keep you safe. To keep our life quiet.” She swallowed. “But love is also letting the truth live. Not hiding it until it turns into poison.”

Thomas felt his throat tighten again. “And loyalty?” he asked, because the word had been haunting him.

Anna’s mouth tightened, then softened. “Loyalty,” she said slowly, “is not always disclosure. Sometimes it is endurance. Sometimes it is silence. But perhaps… perhaps it is also the courage to stop being silent when silence is no longer protection.”

Thomas nodded, because he felt that too.

The next week, Thomas received a letter in the mail addressed to him in careful handwriting. It was from the British Ministry, forwarded through some bureaucratic chain Michael had initiated. Inside was a small bundle of photocopied documents Thomas hadn’t asked for but now couldn’t ignore. Records of Thomas’s unit. Records of translators employed. Names. Dates.

It was nothing scandalous, nothing explosive, but it was proof that the past was not a fog. It was a ledger.

Thomas sat at the table, papers spread out, and felt something in him settle. He had spent decades thinking the war ended when he came home. Now he understood that war ended differently for different people. For some, it ended in medals. For others, it ended in quiet decisions made in leaking rooms.

Anna walked in, saw the papers, and went still.

Thomas held out his hand. “Come sit,” he said.

Anna approached slowly, as if afraid. Then she sat beside him, and together they read, not to punish, not to accuse, but to see. To witness.

Michael’s name was nowhere in those papers. His existence had been held in a different kind of archive, one written in the body and the heart. Still, reading with Anna, Thomas felt like he was finally entering rooms he hadn’t known existed in the woman he loved.

At one point, Anna pointed to a list of translators and traced a finger over her old designation.

“That was me,” she whispered, and the sentence held both pride and sorrow.

Thomas covered her hand with his. “I know,” he said quietly.

Anna’s eyes filled again, but this time the tears fell without shame.

Thomas understood then that the secret wasn’t loud or scandalous. It wasn’t the kind of thing that belonged in gossip. It was buried in paperwork, silence, and sacrifice. It was the kind of secret that didn’t exist to thrill. It existed because the world had once been cruel enough to make it necessary.

And now, forty years later, it had returned not to destroy what they had built, but to force them to rethink what love and loyalty had really cost, and what they might still be, if they were brave enough to hold the truth in the open.

The door, once opened, did not slam again.

It stayed open, letting in cold air sometimes, letting in grief, letting in complicated joy. It stayed open because closing it would not erase the past. It would only return it to the darkness where it had been growing for decades.

Thomas had once believed peace meant quiet.

Now he understood peace could also mean honesty.

And that kind of peace, unlike silence, did not ask one person to carry everything alone.

News

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

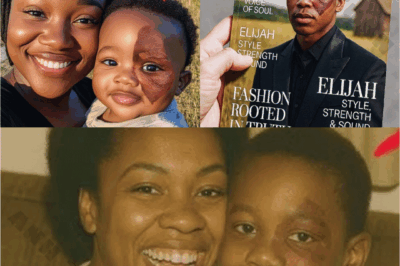

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load