September 19th, 1944 arrived with the kind of cold that made metal feel alive. In Müsterbusch, Germany, the pre-dawn air hung low over the rooftops and shattered masonry, and every sound carried farther than it should have, the clink of track links, the muted cough of engines, the soft, urgent voices of men trying not to wake the whole ruined town. Staff Sergeant Lafayette “Lafe” Pool stood exposed in the commander’s position, gloved hands resting on the rim of the hatch, his shoulders squared against the wind as he scanned the treeline ahead.

The hatch beneath his palms felt like ice.

The order that morning had been clear, almost protective, the kind of instruction you only got when someone above you finally admitted you were too valuable to lose.

“No spearheading today, P. You and your crew are heading home for a war bonds tour. Stay on the flank. Stay safe.”

It was meant like a blessing. It landed like a warning.

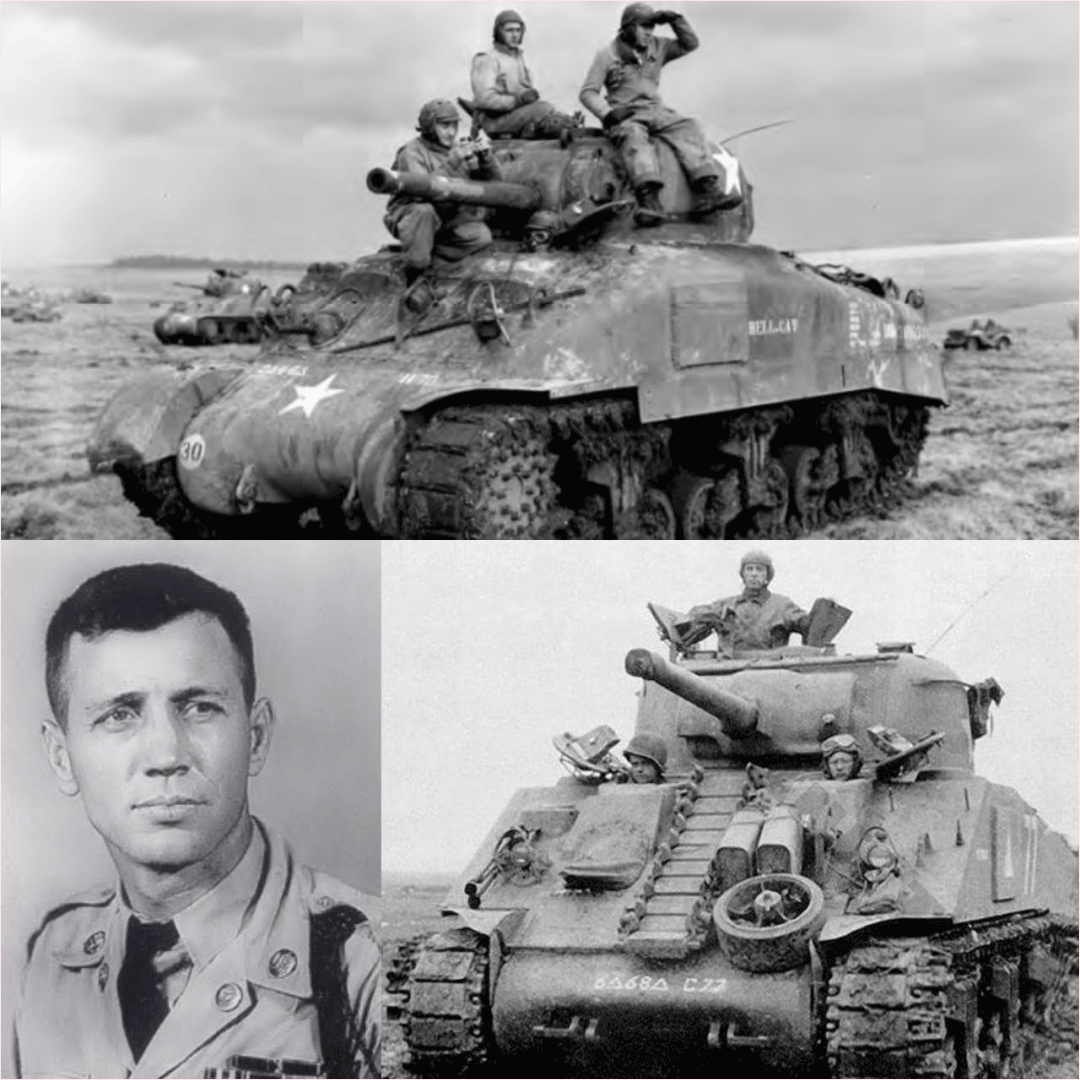

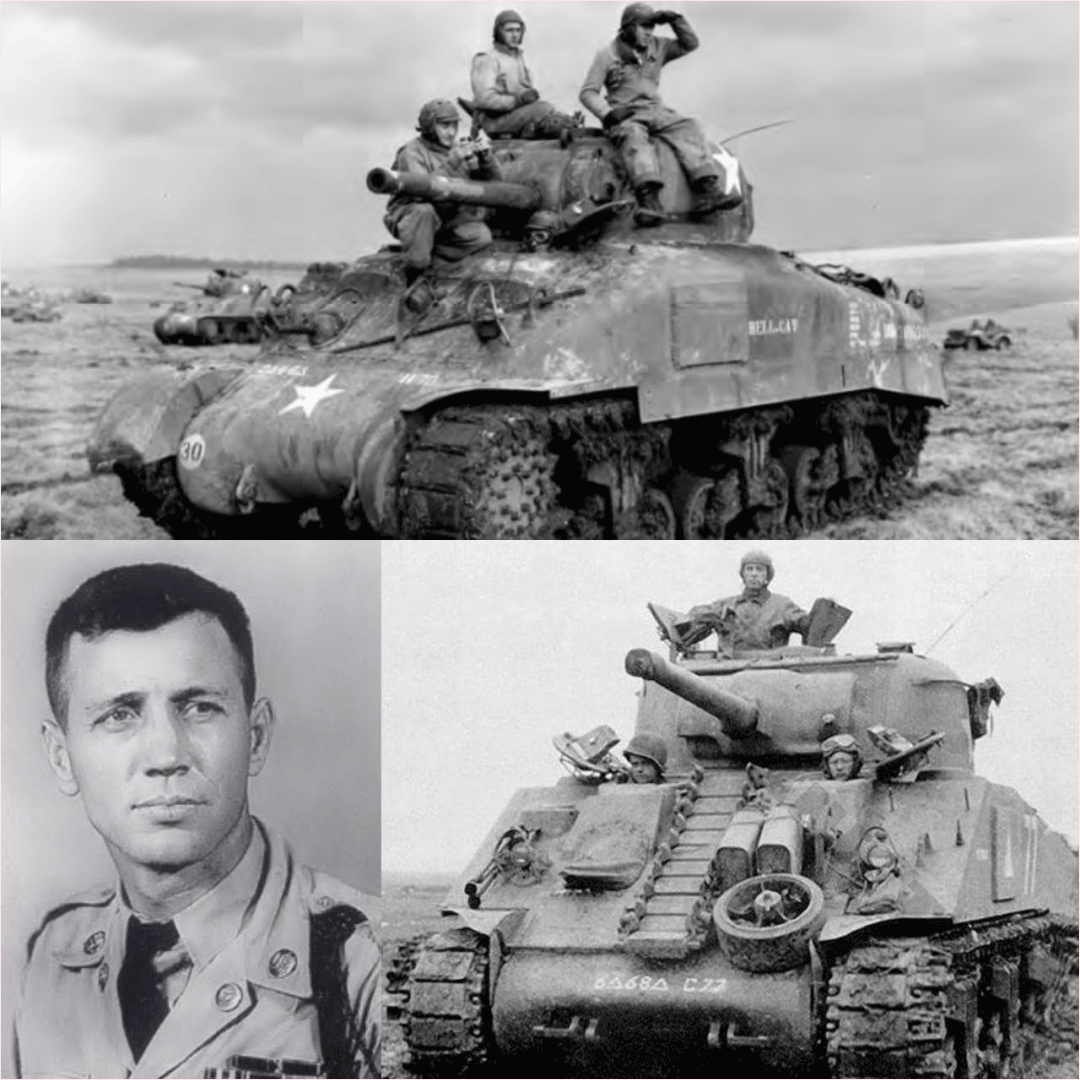

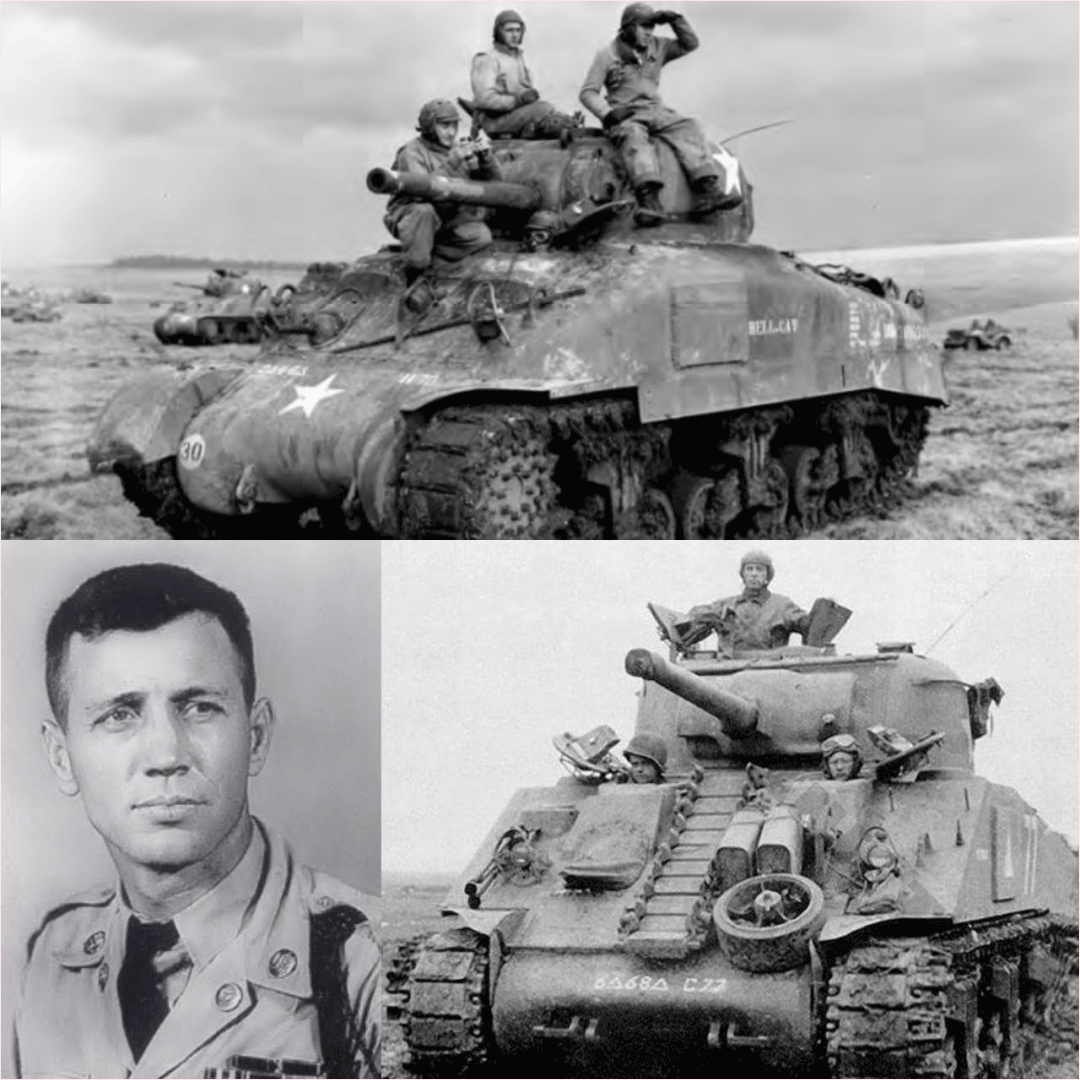

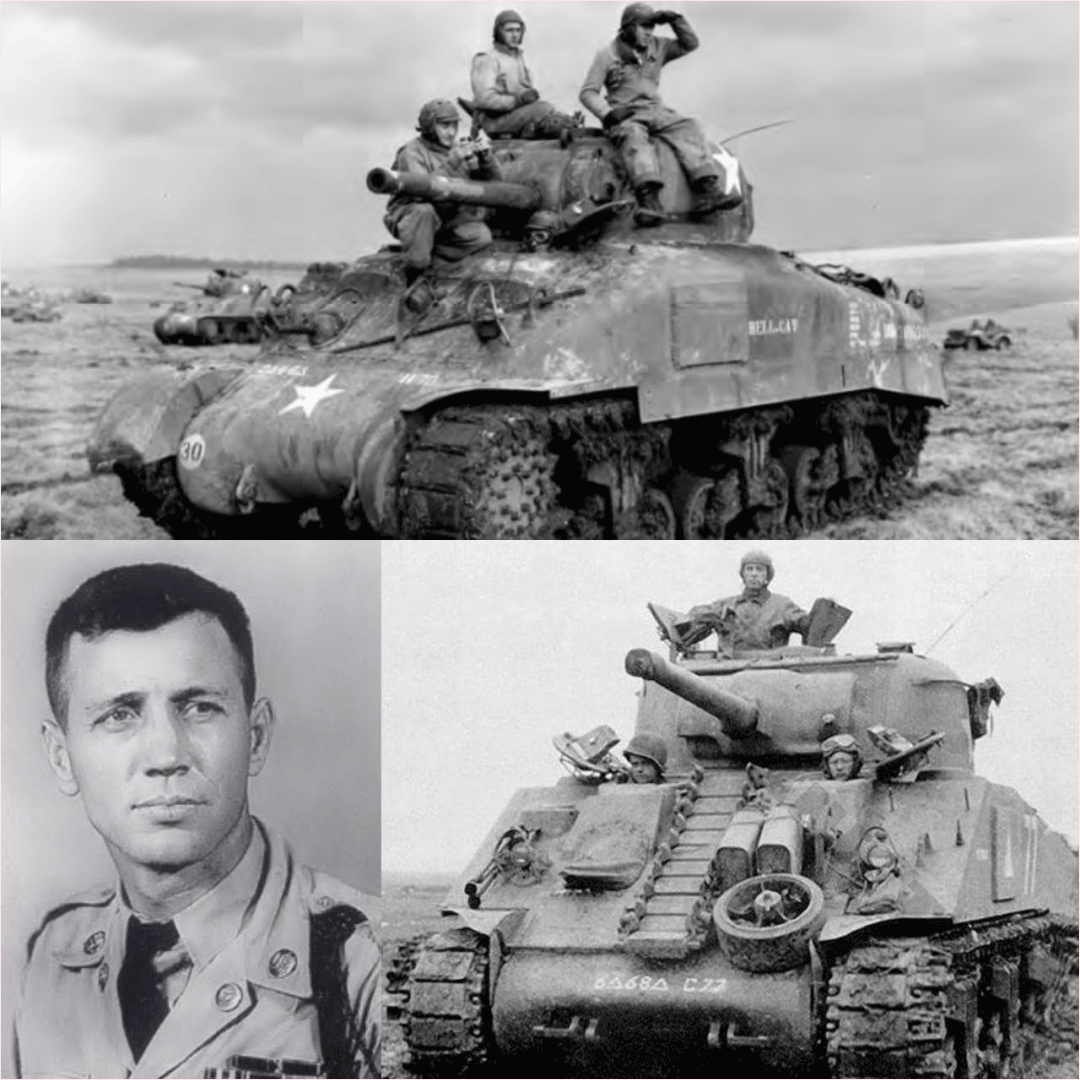

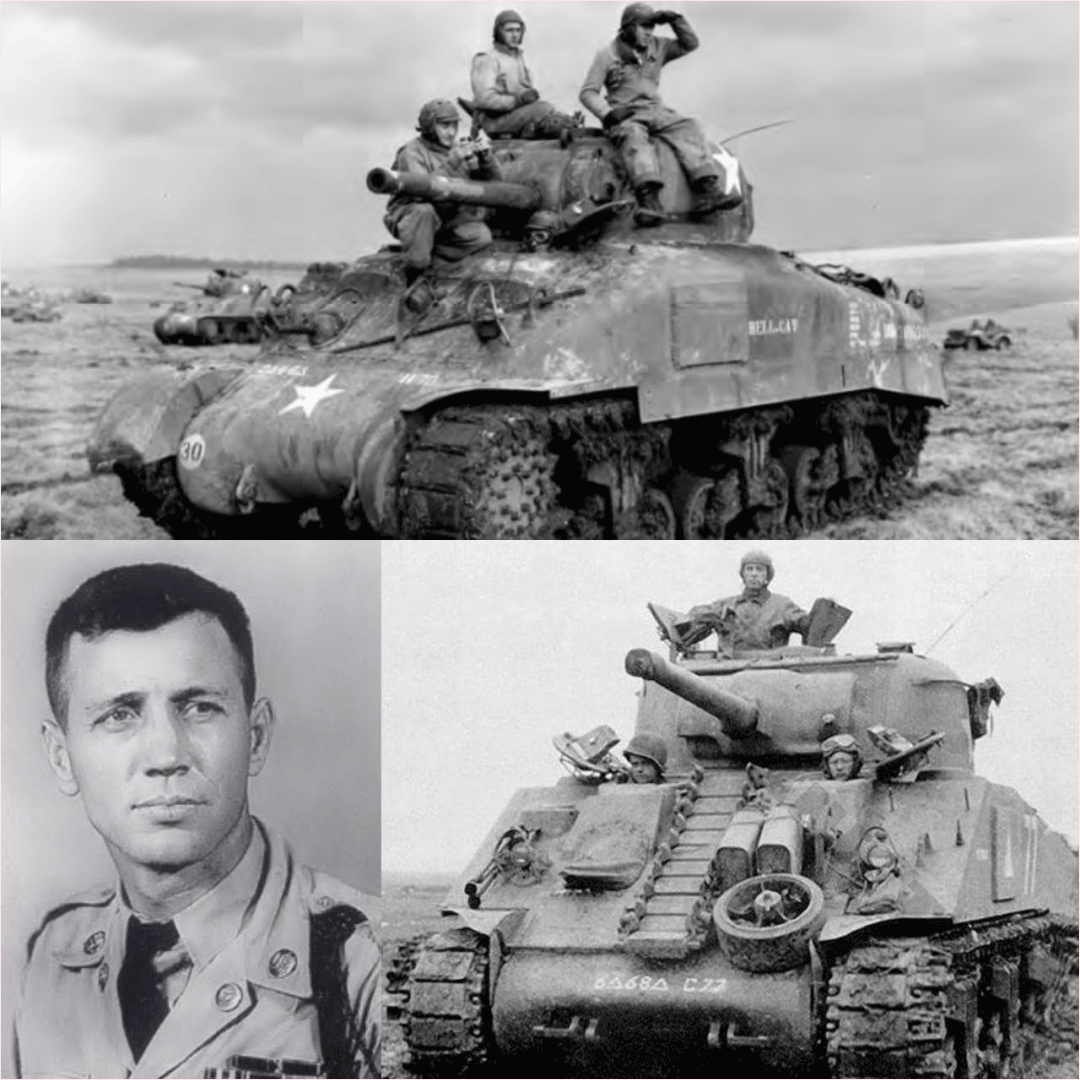

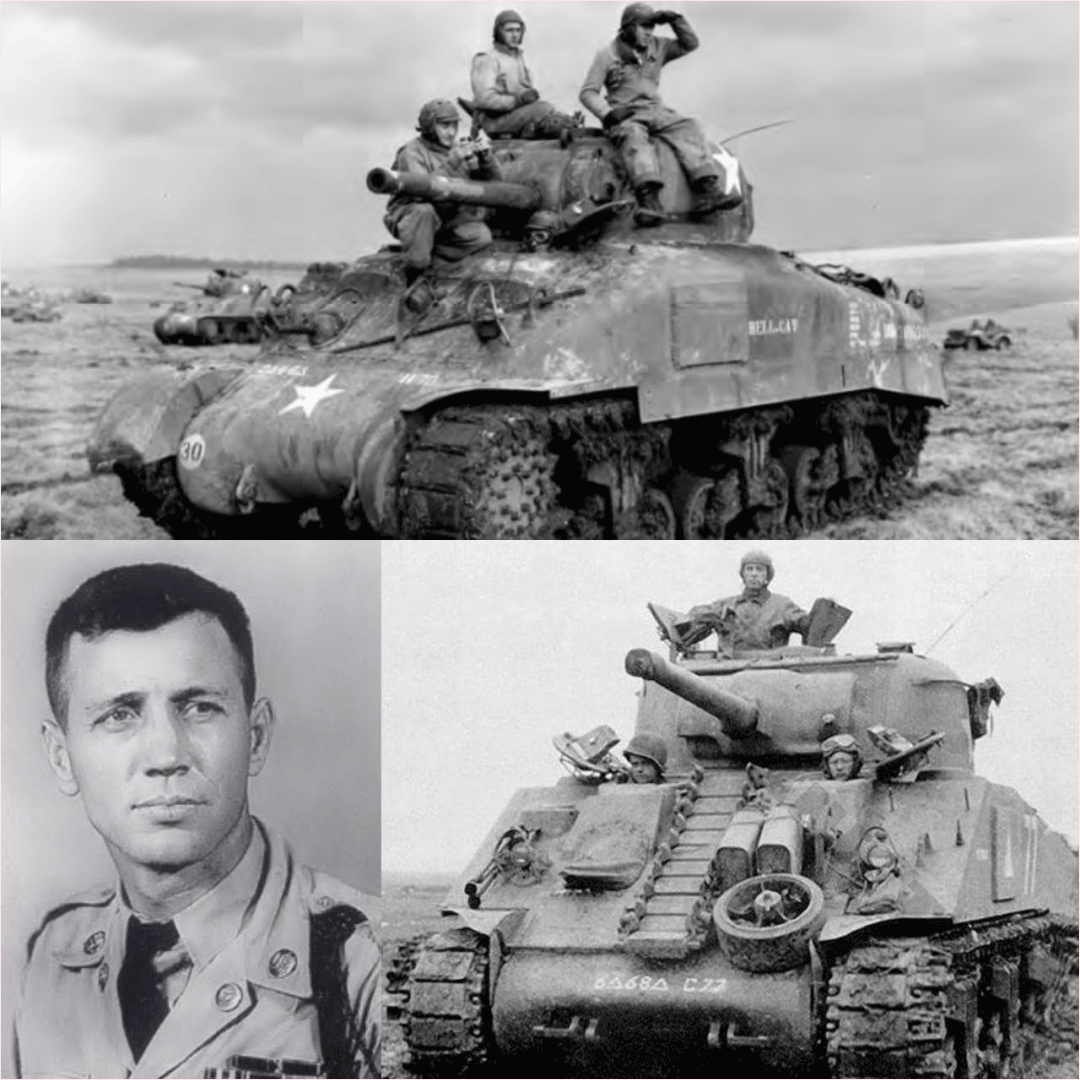

Pool had lived long enough inside a Sherman to learn the one truth that three months of fighting had burned into his bones. In war, safety was an illusion you borrowed for a minute at a time, and the bill always came due. The tank beneath him, painted with IN THE MOOD in white block letters, was the third time those words had been brushed onto American steel under his command. The first two Shermans that carried the name were gone now, burned out husks left on European roadsides. This one, Pool could feel it in the way the morning held its breath, would join them before the hour was over.

The air carried diesel exhaust and the faint, bitter sting of old gunpowder from yesterday’s fight. Somewhere to his left another Sherman clanked into position, its tracks biting cobblestones with a sound like teeth on stone. Pool heard the low chatter of commanders checking positions over the radio, the clipped cadence of men who had learned to talk like the clock was hunting them.

Ahead, hidden in the buildings and rubble of Müsterbusch, German defenders waited with 88s and Panzerfausts. Pool had faced those weapons again and again. He had learned to respect them, to fear them, and to never let that fear lock his hands.

His whole philosophy of tank combat rested on one principle. Strike first. Strike hard. Close the distance before the enemy could make his superior firepower count. That aggression had carried Pool through twenty-one major attacks, through two tank losses, through countless close calls where German rounds missed by inches or ricocheted off armor without finding the seam they needed.

But this morning, with home and “safe” just days away, luck was about to run out.

Pool did not know that yet. He only knew what the cold metal told him, and what the quiet told him. The war was not the kind of thing you walked away from just because the paperwork said you could.

He kept scanning.

Then, as if the world wanted to remind him who made the rules, a distant thump rolled through the dark, and somewhere ahead a shell hit, and the night flashed white for half a second. Pool blinked, steadying his breath.

He could taste the moment. It tasted like the end of something.

Years earlier, he had stood in a different dawn, under a different kind of sky, and signed his name on a piece of paper that would steer him into all of this.

On June 14th, 1941, at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, Lafayette Green Pool put ink to enlistment papers with the steady hand of a young man who thought he understood risk. He was twenty-one, six foot two, lean the way farm boys get when sun and work shape you more than food does. He had hands calloused from rope and plow before they ever learned the controls of a 33-ton tank. When he walked through the recruiting office that day, he carried the dust of South Texas on his boots and the weight of the world in the headlines even if America hadn’t officially joined the war yet.

He had been born five minutes after his twin brother, John Thomas, on July 23rd, 1919, in the small farming community of Odem. He grew up on a farm near the neighboring town of Clinton, on the coastal plains where summer heat could sit above a hundred degrees like a lid, and rain was something you waited for the way you waited for a miracle.

Life on a Texas farm in the 1920s meant labor that started before the sun and ended after it. It meant working cattle, mending fences with wire you had to straighten by hand, patching equipment with whatever scrap could be found or traded. Electricity was a luxury, not a given. Running water came from wells you pumped yourself. Entertainment was radio programs when the batteries held, church gatherings on Sundays, and the small, sturdy comfort of a community that had no time for drama because the land took all your energy.

Pool and his twin were close in that wordless way brothers can be, even with different tempers. John Thomas would join the Navy and serve on ships in the Pacific. Their sister, Tenney May, rounded out the family. Their father, John McKinley Pool, and their mother, Marian Lee Ruth Pool, raised them with hard work, discipline, and service spoken more through example than lectures.

Among family and friends Lafayette went by “Lafe,” sometimes “Leif,” and he had the kind of restless drive that made grown men nod and say, quietly, that boy is going somewhere. He attended Taft High School, graduating in 1937, and he excelled in football, fast and fierce, competitive in a way that didn’t turn off when the whistle blew. But his talent wasn’t only physical. He had a sharp mind and a stubborn appetite for doing things right.

After Taft, he enrolled at Corpus Christi College Academy, an all-boys Catholic prep school known for rigorous academics. He thrived there, applying the same intensity he brought to the field and the farm. In 1938 he graduated as class valedictorian, the kind of achievement that opened doors for a kid who could have been stuck behind a plow his whole life.

From there he went on to Texas College of Arts and Industries in Kingsville, now known as Texas A and M University Kingsville, majoring in engineering. He had aptitude for math and mechanical systems, the kind of mind that liked to understand how things worked, the kind of mind that couldn’t leave a machine alone until it made sense.

During those years, he also found boxing, and boxing found him right back. He competed around 165 pounds, and the sport suited his temperament. Boxing demanded aggression, reflexes, strategic thinking, and the kind of toughness that could take punishment and keep moving forward. Pool proved exceptional, compiling an amateur record of forty-one wins with no defeats. His aggressive style and heavy hands earned him a sectional Golden Gloves championship in New Orleans. The National Golden Gloves invited him to compete in the finals, an invitation that could have launched a professional career.

Pool declined.

He had other plans. Engineering called to him more than the uncertain life of a fighter. But the discipline boxing carved into him, the instinct to strike first, to take the initiative, to keep your head clear under pressure, would follow him into a different ring entirely.

By 1941, the world was already on fire. Germany had conquered most of Europe. Britain stood alone. Japan expanded across Asia. America still called itself neutral, but nobody with eyes believed that would last. Young men everywhere faced the same choice. Wait to be drafted, or enlist and get some say in where you went.

Pool decided he would not wait for history to grab him by the collar.

When he walked into Fort Sam Houston, it was six months before Pearl Harbor. He signed with the Army. He was twenty-one, about 175 pounds, conditioned like an athlete, disciplined like a scholar, and the Army would take that raw material and turn it into something else entirely.

A tank commander.

The deadliest in American military history.

His introduction to mechanized warfare came with the newly forming Third Armored Division at Camp Polk, Louisiana. The division had been activated on April 15th, 1941, part of America’s massive buildup in anticipation of war. It would earn the nickname Spearhead for its role in penetrating German defenses across France and into Germany itself. Always leading the advance, always pushing deeper than units behind it.

Pool was assigned to Company C, Third Battalion, 32nd Armored Regiment, serving as a tank commander in Third Platoon. It was an assignment that would define his life in ways he could not imagine standing in that recruiting office in San Antonio.

The Third Armored Division represented America’s commitment to mechanized warfare, a concept that had already proven devastating in German hands. Its structure reflected lessons drawn from Panzer operations. It combined tanks with armored infantry, artillery, engineers, and support units trained to operate together as a cohesive force. The striking power came from tank battalions equipped at first with the M3 Lee, a stopgap design, a 75mm gun in a hull sponson and a 37mm in a turret. It was obsolete almost as soon as it arrived, but American production in 1941 couldn’t deliver better designs in sufficient numbers yet.

The M4 Sherman, which would become the standard American medium tank, was just entering production when Pool joined.

Training at Camp Polk was intense and punishing. Pool and his fellow tankers learned to operate, maintain, and fight from armored vehicles in every conceivable condition. They practiced gunnery until target identification and engagement became muscle memory. They learned radio procedures for coordinating with other tanks, infantry, artillery. They studied German tactics and equipment, learning the capabilities and vulnerabilities of the panzers they would eventually face. They conducted endless field exercises, simulating attacks, defenses, pursuit operations. The Louisiana countryside, with its forests and swamps, became their classroom, terrain that could mimic the confined fight they’d someday face in Europe.

Pool’s aggression marked him early. Officers noticed it, the way he refused to accept second place in anything. In gunnery, his tank scored among the highest. In tactical exercises, he showed an intuitive understanding of terrain and enemy positions that went beyond what any classroom could teach.

He studied tanks the way he’d studied engines back in school. How they moved, how they fought, where they broke. He learned to read terrain like a book, identifying positions with good fields of fire, concealment, routes of advance and withdrawal. He recognized how a competent enemy would think, where an ambush would be laid, where a gun would be hidden, where the kill zone would be.

Most of all, he demonstrated leadership.

The men under his command respected him. Trusted him. Would follow him anywhere. But that trust was never granted for free. Pool earned it the way all real trust is earned, day by day, through standards that didn’t bend when fatigue tried to bargain.

He demanded perfection from himself and his men. Endless gunnery drills. Driving practice. Tactical maneuvers until their hands and eyes moved without conscious thought. He was not cruel in his demands. He simply understood the arithmetic of combat. A well-trained crew lived. A mediocre one died.

Every second saved in target acquisition meant firing first. Every round that hit meant one less enemy tank shooting back. Every correct radio call meant better coordination, better support. Load, aim, fire, reload became a rhythm as natural as breathing. Identify target, assess range, adjust fire, repeat, until it was instinct.

When the opportunity came to receive a commission as an officer, Pool refused it. Commissioned officers commanded from higher up, coordinating multiple tanks from command posts. Pool wanted to fight from a tank, to lead from the front where he could see the enemy with his own eyes and make split-second decisions with the truth right in front of him.

He preferred to remain close to his crew, close to the fight.

That decision would define him. Staff sergeants did not normally command platoons in combat, but Pool’s skill and leadership would see him doing exactly that, trusted to accomplish missions that should have belonged to lieutenants and captains.

Training rolled through 1942 and into 1943. The Third Armored Division deployed to the Desert Training Center in the Mojave, California and Arizona, where the vast open spaces and harsh conditions prepared units for combat that might come in North Africa. The desert tested men and machines under extreme heat and choking dust. Metal expanded. Seals failed. Systems overheated. Tank commanders learned dead reckoning across featureless wastes. Crews learned maintenance under conditions that punished every weak point.

After desert training, the division moved to Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania for final preparation before deployment overseas. Rolling hills and forests resembled European terrain more closely than Louisiana swamps or California deserts. Here the division sharpened combined arms tactics. Tanks advanced with infantry support. Artillery coordinated. Engineers stood ready to breach obstacles and clear mines. Radio discipline improved. Maintenance procedures tightened. Weak points were identified and corrected.

By late 1943, the division was as ready as training could make it.

During those training years, Pool’s life still contained flashes of ordinary America, moments that felt almost indecent against what was coming. In December 1942, while on leave, he married Evelyn Wright. It was a brief pocket of normal, a wedding that carried the unspoken knowledge that the Army might take him away and not return him. Evelyn would wait through the war, letters traveling in thin paper across the Atlantic, words that held him up when the days turned dark. They would build a family that eventually included eight children, four sons and four daughters, and their marriage would endure nearly fifty years, a bond built in the shadow of a world at war.

In September 1943, Pool and the 32nd Armored Regiment boarded troop ships in New York Harbor. They crossed the Atlantic packed into converted passenger liners and cargo ships, sleeping in cramped quarters, enduring rough seas and the quiet dread of U-boats.

The convoy zigzagged to avoid submarine wolf packs. Destroyers patrolled the edges, dropping depth charges when sonar contacts hinted at danger. Men played cards, wrote letters, stared at the ocean, and tried not to imagine the cold black water swallowing them if a torpedo hit.

Pool arrived safely in Liverpool in late September 1943.

The Third Armored Division spent the next nine months in England, September 1943 to June 1944, training, staging, preparing for the cross-channel invasion everyone knew was coming. They trained across the English countryside near Liverpool and Bristol in Somerset, learning to work with British units, receiving final equipment and replacements. The waiting was its own kind of torture. Rumors never stopped. Security was tight. Training never ended. You lived in a constant state of almost, as if history was holding its breath.

During that period, Pool experienced his first and only defeat in a ring.

Joe Louis, the heavyweight champion known as the Brown Bomber, toured England, putting on exhibitions for the troops. Louis was a cultural icon, his victories symbols of American strength and resolve. His second win over German boxer Max Schmeling in 1938 had carried political weight far beyond sport, a repudiation of Nazi racial theory delivered with gloves.

Now Louis used his fame to boost morale. He sparred with servicemen in friendly bouts. Most soldiers didn’t want any part of stepping into the ring with the heavyweight champion of the world.

Pool volunteered anyway.

The bout was scheduled for July 4th, 1944, Independence Day in Liverpool. It was supposed to be light, friendly, entertainment. But Pool’s competitive instincts didn’t know how to play pretend. He went after Louis aggressively and landed several solid blows that surprised the champion.

Louis stepped in close, put an arm around him, and said in a voice only Pool could hear, “White man, I’m going to teach you a big lesson.”

The lesson arrived fast and complete. Louis dominated him with speed, power, technique, turning Pool every which way but loose without actually hurting him. Louis could have knocked him out whenever he wanted. Instead, he demonstrated the gulf between an amateur’s hunger and a professional’s mastery.

Pool walked away bruised in pride but sharper in mind.

He learned that aggression alone was not enough. Timing mattered. Skill mattered. Tactical intelligence mattered. You could not just throw yourself forward and expect to win. You had to choose your moment and make it count.

Those lessons followed him, invisibly, toward Normandy.

On June 23rd, 1944, at the port of Weymouth, England, the Third Armored Division began boarding ships for the crossing. D-Day had happened June 6th, eighteen days earlier. The beaches had been secured, the push inland had begun, and now follow-on units like the Third Armored would join the fight.

The tanks and vehicles were waterproofed for landing. Protective covers and seals wrapped every opening to keep seawater out during the wade from landing craft to shore. The prep was thorough, but men stayed nervous. They had heard stories of Omaha, of casualties, of desperate hedgerow fighting. Now it was their turn.

On June 24th, 1944, the division came ashore at Omaha Beach in a steady rain that turned the sand into mud and the whole place into controlled chaos. The beach still bore the scars of the invasion. Wrecked landing craft lay half-submerged in the surf. Destroyed fortifications dotted the cliffs. Massive dumps of ammunition, fuel, rations, equipment covered every open space. Military police directed traffic, trying to keep order as thousands of vehicles moved inland toward assembly areas.

The smell of salt water mixed with diesel exhaust, wet earth, and the lingering odor of explosives.

Pool’s first Sherman, an M4A1 with a 75mm gun, came ashore without incident. Waterproofing held. Engine started. The tank ground up the beach under its own power as if it had been born there, as if the ocean itself was only another obstacle to solve.

Over the next days, the division assembled, removed waterproofing, test-fired weapons, performed maintenance, and prepared for combat. Pool’s crew had trained together for months, the kind of synchronized precision that turned five men and a machine into a single organism.

Pool had personally chosen each member, matching skill and temperament to his aggressive approach.

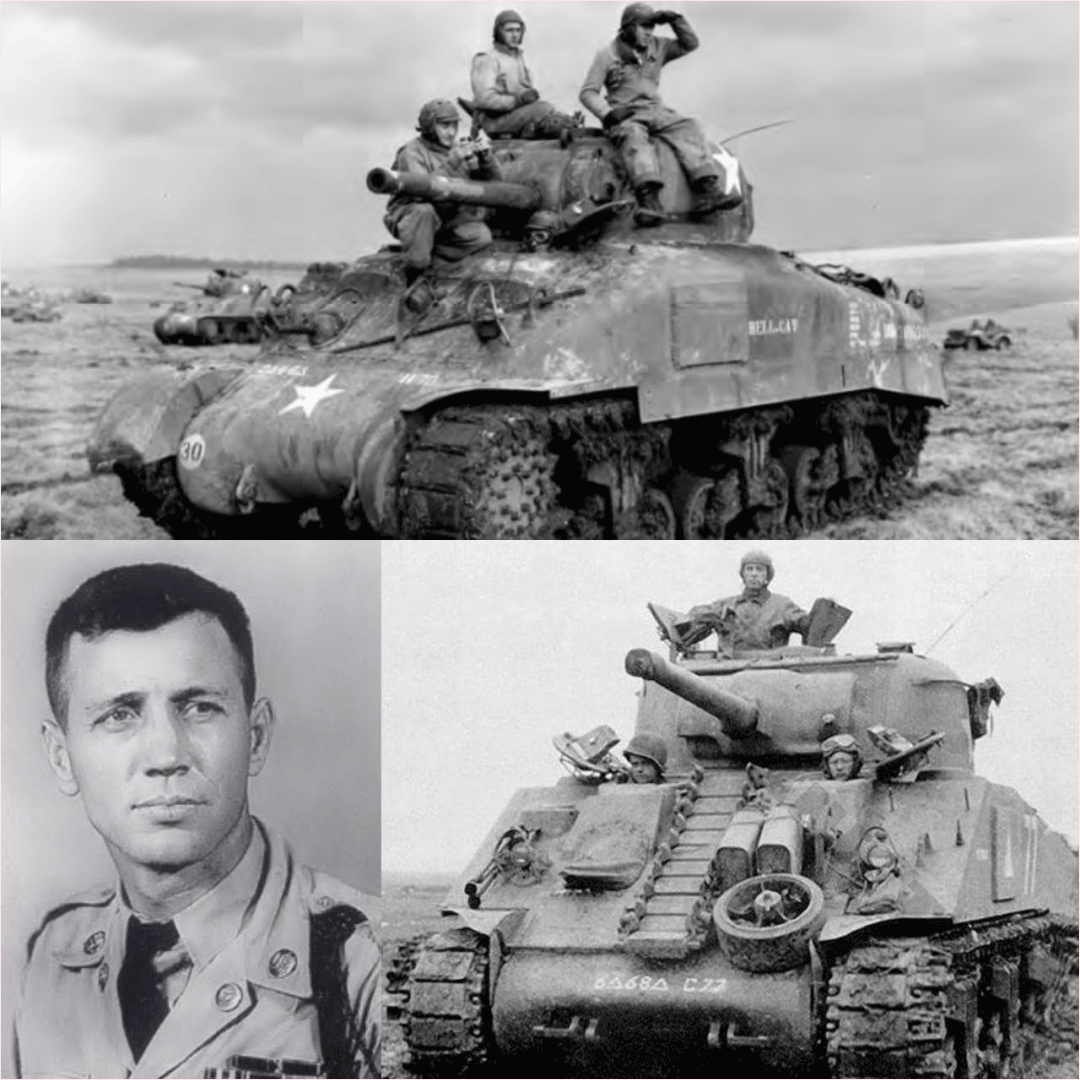

Corporal Wilbert Richards, called Baby because of his baby-faced look, served as driver. He was only five foot four, compact and wiry, but he could maneuver a Sherman with a finesse that bordered on impossible. Pool used to brag that Baby could parallel park a 33-ton Sherman in downtown New York during rush hour, an exaggeration that carried an essential truth. Richards could thread the tank through narrow village streets, reverse at speed under fire, place the hull at an angle that made the difference between a ricochet and a penetration.

Richards drove with his hatch open whenever possible. During training he had once been trapped inside a tank when a hatch jammed, and the memory left him with a fear that every tanker shared, but that lived sharper in him. The open hatch gave visibility and a faster escape route if they were hit, even if it meant more exposure to fragments and small arms fire. It was a gamble, like everything else.

Private First Class Bertrand Close, seventeen years old and called Schoolboy for his youth and wire-rim glasses, served as assistant driver and bow gunner. He operated the .30 caliber Browning mounted in the front hull. Close came from Portland, Oregon and looked like what he was, a teenager, slight build, smooth features, almost too young to be in a war. But inside the tank he was vicious with that bow gun, cutting down enemy infantry with precise bursts. His field of fire forward and to the right covered approaches used by infantry trying to get close enough for Panzerfausts or mines.

Close also assisted with loading during intense fights, passing rounds from racks to the loader when seconds mattered.

Corporal Willis O’Brien, twenty-nine years old, nicknamed Groundhog, was the gunner. He came from Illinois, older than the rest, calm and methodical, his temperament a counterweight to Pool’s intensity. He seemed to see all of France through his gun sight, face perpetually marked by the imprint of tanker goggles, eye pressed to the optic as if he could will targets into existence.

Gunning was demanding in a way that exhausted you without mercy. Identify target. Judge range. Select ammunition. Aim while moving. Fire at exactly the right moment. Do it in seconds, under fire, with the tank rocking and smoke choking the view. O’Brien excelled at it. His shots would validate Pool’s faith again and again.

Technician Fifth Grade Delbert Boggs, twenty-two from Lancaster, Ohio, called Jailbird, served as loader. The nickname came from a story crew lore repeated until it became part of him. Boggs, they said, had faced manslaughter charges and been given a choice, prison or the Army. He chose the Army. Whether the story was fully true or partly embroidered, it fit his character. Tough. Street-wise. Absolutely reliable when the world turned violent.

The loader’s job was brutal. A 75mm round weighed around twenty-five pounds. The 76mm rounds they would later use weighed even more. In a fight, the loader might handle dozens of rounds, selecting the right type on command, loading smoothly in cramped space while the tank jolted, then preparing the next round without hesitation. Boggs was skinny but possessed wiry strength and endurance, and his speed gave Pool a rate of fire that outpaced most Shermans.

These men called themselves the Pups. They called Pool War Daddy, a nickname that held affection and respect. It came from the dynamic Pool created during training, intensely focused on preparation and just as intensely protective of his crew’s welfare. He was not much older than some of them, younger than O’Brien, but his force of personality made him the center of the tank. They trusted him because they knew he demanded everything and also gave everything.

The crew regularly outscored others in gunnery efficiency. Their teamwork was seamless. When Pool called a fire command, they responded with machine-like precision.

Driver, stop.

Gunner, sabot, tank, front. On the way.

Boom.

In a well-trained crew the sequence from spotting to firing might take five seconds. Pool’s crew could do it in three. In tank combat, those seconds were life.

Pool’s tactical philosophy was simple and brutal. Shoot first. Shoot to kill. Always go forward. Never retreat. German tanks like the Panther and Tiger had thicker armor and guns that could kill a Sherman at ranges where the Sherman could not penetrate their front. Pool’s solution was to refuse the long-range duel. Close the distance. Maneuver for flank shots. Use speed, rate of fire, and crew coordination to overwhelm the enemy before their technical advantage could settle into the fight.

Pool was claustrophobic. He preferred to ride exposed in the turret or even on top of the tank instead of buttoned up inside, and that choice was both weakness and strength. Exposed, he was vulnerable to fragments, small arms, concussion. Many commanders died from fire that would not have penetrated the armor if they’d stayed inside. But up there, Pool could see. He had situational awareness commanders buttoned up could not match. He spotted threats earlier. Identified targets faster. In tank warfare, seeing first usually meant shooting first, and shooting first usually meant living.

His battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Walter Richardson, another Texan, recognized Pool’s ability and trusted him. Richardson said Pool rode his tank like a bucking bronco, exposed and unafraid, always leading from the front. Richardson called on him for dangerous missions that would normally fall to officers.

Pool never refused.

Before Pool’s Sherman went into combat, it needed a name. Tank crews painted names the way sailors named ships, personalizing the steel they lived in. Pool chose IN THE MOOD, taken from Glenn Miller’s swing hit, a song that had lifted American spirits since 1940. In mess halls and on radios, that tune had become part of the sound of home, the promise that the world could still dance even while it burned. The name suited Pool’s approach to combat, confident, aggressive, relentless.

On June 29th, 1944, near Villiers-Fossard northeast of Saint-Lô, Combat Command A received orders to reduce a German salient held by a reinforced fusilier battalion of the 353rd Infantry Division. It would be the Third Armored Division’s first combat operation.

It would be Pool’s first taste of battle.

The mission was to attack a salient about 3,000 yards deep, a position anchored in the Normandy hedgerows. The hedgerows were older than the war, earth walls crowned with dense vegetation, lining fields and roads, turning the countryside into a maze of natural fortresses. They channeled movement and offered concealment for ambushes. German infantry and anti-tank guns could hide behind them until Americans were almost on top of them. Tanks climbing over exposed their belly armor. Early American attacks in Normandy had been costly disasters.

Engineers developed an answer by cutting steel beams from German beach obstacles and welding them onto Shermans, creating rhino tanks that could punch through hedgerows without climbing. It changed the tactical situation. It gave armor a way to break the maze open.

At 0900 hours, Combat Command A launched the attack. Artillery pounded German positions for thirty minutes. The air filled with shrieks and thunder. Then tanks moved forward, grinding into the countryside, visibility limited to the next hedgerow, sometimes only fifty yards away.

Radio chatter filled Pool’s headset. Contacts called out. Requests for artillery. Coordination. The crack of German 75mm anti-tank guns answered by the deeper boom of American tank guns. Black smoke drifted across fields. The world narrowed to what you could see through gaps in green and what you could hear through the metal hull.

Pool spotted German vehicles ahead through a break in the hedgerow.

“Half-track, ten o’clock, three hundred yards.”

He gave the fire command and O’Brien sent a high explosive round downrange. It hit the vehicle squarely. It erupted in flame.

Pool’s crew destroyed three German vehicles and killed over seventy enemy soldiers that first day. The violence was everything training hinted at and nothing it could fully deliver. Noise overwhelming. Fear real. Adrenaline turning time strange. Yet the drills took over. Pool moved aggressively, refused to yield ground. His crew performed like they had been built for this moment.

Then came the thing every tanker feared.

IN THE MOOD entered the village of Le Désert, advancing down a narrow street between stone buildings. Intelligence said the village was clear. Combat laughed at intelligence. A German soldier stepped from a doorway with a Panzerfaust, aimed, and fired from less than fifty yards.

The rocket slammed into the Sherman’s side with a crash that rang through the compartment. The shaped charge detonated, a jet of superheated metal punching through. The tank shuddered. Smoke filled the interior. Alarm and instinct took over.

“Bail out!”

They moved with the practiced speed that training had drilled into muscle. Pool was first out the commander’s hatch, then O’Brien. Richards and Close scrambled out the driver and assistant driver hatches. Boggs forced himself through the loader’s hatch. They got clear before the worst could happen.

The first IN THE MOOD was destroyed.

Five days in combat.

The crew rejoined Task Force Y on foot, catching rides on other tanks until assigned a replacement. The battle for Villiers-Fossard continued through June 30th, and Combat Command A lost thirty-one tanks and twelve other vehicles in two days, a harsh introduction to what armored warfare cost in Normandy. But the attack succeeded. The Third Armored Division held the ground until relieved by infantry.

On July 1st, 1944, somewhere in Normandy, Pool and his crew received a replacement tank, an M4A1 with the 76mm gun, the M4A1(76)W, wet stowage. Pool was the first tank commander in his regiment to receive this upgraded variant, recognition of performance and a bet placed on his future.

The wet stowage mattered. Early Shermans had a reputation for burning when hit, earning cruel nicknames. Wet stowage surrounded ammunition racks with containers of water and glycol mixture that reduced catastrophic fires. It did not make a Sherman invincible. It made it less likely to become a funeral pyre.

The 76mm gun mattered too. It improved armor penetration. It gave the Sherman a better chance against Panthers and Mark IVs, especially on side shots and at closer ranges. The tradeoff was a less effective high explosive round compared to the 75mm, slightly weaker against infantry and soft targets. For Pool, who hunted armor and closed distance, the improved anti-armor capability was invaluable.

Pool had IN THE MOOD painted on the new hull immediately. The name stayed. The spirit stayed.

The crew climbed aboard, learned the differences, the new balance, the internal arrangement of racks, the weight of the longer gun. They made it theirs.

Over the next weeks, the hedgerow fighting tested every nerve. Advance to a hedge. Take fire from the next. Call artillery. Assault through under covering fire. Clear the field. Move to the next hedge. Repeat. The Normandy countryside turned every day into a series of ambushes waiting to happen. German 75s and 88s hid behind walls. German infantry with Panzerfausts slipped close at night. Casualties were high.

Pool’s instincts sharpened into something like a sixth sense. He read shadows and sight lines, patterns of vegetation, subtle disturbances that suggested a gun position. He learned to think like the enemy, to anticipate where an experienced German crew would place its trap.

He spotted threats before they fully revealed themselves.

He engaged first.

He killed positions before they could kill him.

Once at dusk near a small town, as the crew prepared to settle in for the night, a shape materialized perhaps fifty feet ahead, a German 40mm anti-aircraft gun emplacement. The German crew moved like men who believed the day was over. Pool recognized he had only seconds.

He did not whisper. He did not hesitate.

“Gunner, fire!”

O’Brien was already on the sight. The 76 roared. The round hit square. The gun and crew vanished into flame and debris. Three seconds from sight to impact. Training turned into reflex. Reflex turned into survival.

Another night near a hedgerow lane, Pool’s platoon advanced cautiously in darkness, a time when tanks were blind and infantry could get dangerously close. Night movement was risky, full of friendly fire accidents and sudden ambushes. Yet the tactical situation demanded it, and Pool pushed forward.

Then IN THE MOOD almost collided with a German Panther at a range so close it felt unreal. Two armored beasts found themselves face to face in the dark, maybe thirty yards apart.

On paper, the Panther should have ended them.

The Panther’s gun could kill a Sherman from far beyond what the Sherman could answer. Its front armor was nearly immune to American fire except at weak points. Stories about German super tanks traveled through units like ghost tales.

But combat was not fought on paper.

Both commanders reacted at once. Both gave fire orders. The Panther fired twice, shots rushed and blinded by surprise and darkness. Both rounds missed. One cracked over the turret. One hit ground and ricocheted upward, missing belly armor by inches.

O’Brien’s shot went true.

A 76mm armor-piercing round at point-blank range penetrated the Panther at the turret ring, a vulnerable seam. The round detonated inside. The Panther erupted into flame, lighting the night orange, destroying Pool’s night vision but also revealing silhouettes of other threats in the area.

Pool immediately backed away from the burning Panther before ammunition inside could detonate catastrophically, and he called for his platoon to engage additional targets while the enemy reeled.

Ten seconds from contact to kill.

A duel won through crew work, speed, discipline, and the ruthless advantage of shooting first.

Word spread. American tankers feared Panthers and Tigers for good reason, but Pool proved they could be killed. Aggressive tactics and disciplined crews could negate technical superiority. His example pushed other commanders to fight forward, to close distance, to refuse long-range death.

By late July, Operation Cobra began, and the war changed shape.

On July 26th, 1944, one of the most concentrated bombing campaigns in military history pulverized German positions south of Saint-Lô. Heavy bombers and mediums dropped thousands of tons of bombs, intended to shatter defenses and open a gap for armor to pour through. The plan worked, though friendly fire tragedies took American lives too, including Lieutenant General Leslie McNair. The German line broke. Surviving defenders were dazed, disorganized, incapable of coherent resistance.

The Third Armored Division led the exploitation, punching through on July 29th and racing into open country. After weeks of grinding hedgerow fighting where progress was measured in yards, they found themselves in a war of movement. Tanks ran roads at speeds that felt illegal. German units tried to retreat and found escape routes cut. Thousands surrendered. Others were crushed under speed and fire.

Pool spearheaded again and again.

Spearheading was both honor and death sentence. The lead tank met the ambush first, the mine first, the Panzerfaust first. Casualty rates were brutal. Pool volunteered anyway. His crew did not question him. They trusted War Daddy to get them through.

And somehow, against the odds, IN THE MOOD kept rolling. Kept killing. Kept surviving.

In Belgium, near Liège, Pool led as platoon leader because officers were scarce. His column took fire from the left. German half-tracks and armored cars trying to escape the encirclement stumbled into his path. Pool ordered his column to continue advancing while he turned to deal with the threat. He closed to effective range and destroyed six vehicles quickly, forcing the rest to scatter.

Then came word over the radio that a Panther had appeared ahead, engaging his column. Pool made the choice that defined him. He did not finish the mop-up. He went where the danger was.

“Richards, get us back. Now.”

IN THE MOOD raced down the road at a speed that felt like daring the universe. Pool scanned. Boggs loaded armor-piercing. Close watched flanks. The engine strained. The Sherman’s suspension clattered over uneven ground.

Pool spotted the Panther hull-down behind a rise, methodically killing Shermans. Two were already burning. Crewmen bailed out through smoke, silhouettes against flame. The Panther’s attention stayed forward. It had not spotted Pool coming from the flank.

Pool recognized the opportunity instantly.

“Gunner, sabot, Panther, left flank.”

O’Brien traversed, smooth and fast. Crosshairs settled on side armor under the turret ring. The 76 fired. The round penetrated. Smoke poured from hatches. Then fire. The Panther died, and a moment later its ammunition detonated, blowing the turret with a violence that reminded everyone watching how thin the line between armor and coffin really was.

Pool returned to the spearhead by earned right, not assigned duty.

In the Falaise gap fighting, the battle turned chaotic, desperate, units intermixing, meeting engagements, ambushes. German soldiers tried to flee on foot after abandoning vehicles. Pool closed on a group. Over the radio his voice came through, low and human for a second.

“Ain’t got the heart to kill them.”

Then the bow gun opened up, Close stitching the ground with .30 caliber fire, and Pool’s voice returned, hard again, the war pulling the softness out of him like smoke out of a wound.

“Watch the bastards run. Give it to them, Close.”

It was the moral complexity of combat in a single exchange. Good men doing terrible things for tactical necessity, knowing that if you let the enemy escape today, you fought him tomorrow, and tomorrow cost American lives.

From August 29th through 31st, 1944, Pool’s actions would earn him the Distinguished Service Cross. He advanced ahead of his task force, often alone or with minimal support, drawing fire and destroying enemy armor in separate encounters. Tanks. Assault guns. Anti-tank guns. Unarmored vehicles. Over three days he and his crew fought as if the world had narrowed to the gun sight and the next breath, and they kept winning because their decisions were faster, their drill tighter, their will sharper.

The citation would later say his courage permitted rapid advance with minimal casualties. It would speak of devotion to duty and the highest traditions. It would not fully capture what it felt like inside the turret when every enemy weapon on the map seemed aimed at you and you still chose to move forward.

Then came a different kind of disaster.

During the pursuit across France, American P-38 Lightnings appeared overhead hunting for German armor. From thousands of feet up, tanks looked like tanks. The pilots misidentified Pool’s Sherman as enemy. Rockets streaked down, trailing smoke. They hit around and on IN THE MOOD. Explosions tore into the tank.

Pool did not have time to argue with the sky.

“Out! Out!”

They bailed with the practiced speed of men who had rehearsed dying a hundred times. Flames took the Sherman. Ammunition cooked off. The second IN THE MOOD was destroyed, not by German steel, but by friendly fire.

It devastated them in a way enemy action did not. They had survived ambushes, Panthers, Panzerfausts, the hedgerows of Normandy. Losing a tank to their own air support felt like betrayal even when it was only mistake.

Within days, they received a third Sherman, another M4A1(76)W, and Pool had the words painted on again. IN THE MOOD. The tradition continued. The name became a signal throughout the Third Armored Division. That was Pool’s tank. That was War Daddy’s crew.

By early September, their tally climbed into territory that sounded like propaganda until you saw the burned-out evidence along roads and in fields. Over 250 enemy vehicles destroyed. At least twelve confirmed tank kills. Prisoners captured in bulk when resistance collapsed under the shock of aggressive armor that never seemed to stop.

Division headquarters understood Pool’s value. They also understood probability. Even the best luck eventually ran out. Orders came down. Pool and his crew would be sent home for a war bonds tour. Their story would sell bonds, inspire the home front, put living proof of victory on stages under bright lights in American towns where people still bought Coca-Cola and danced on Saturday nights.

They had earned it.

They just had to survive one more mission.

That was why, on September 19th, 1944, in Müsterbusch, the order had been protective. No spearheading. Stay on the flank. Stay safe.

Pool obeyed as far as his nature allowed. The attack began at first light. Tanks advanced with infantry alongside, clearing buildings, suppressing anti-tank weapons. German resistance was immediate and fierce. This was German soil now. Every yard would be contested. Artillery crashed. Mortars burst. An 88 cracked in the distance and Shermans began to burn.

Pool moved on the flank as ordered, providing covering fire. The crew worked with the efficiency born of months of combat. Close watched the approaches with the bow gun. Richards positioned the hull as Pool directed. Boggs kept rounds moving. The gunner that morning was not O’Brien.

O’Brien had been rotated out, sent back to the United States as part of routine rotation for veterans, rest and training duty. In his place sat Private First Class Paul Kenneth King, twenty years old from Anderson County, Tennessee, capable and willing, but without three months of combat synchronization with this crew.

That small change mattered in ways nobody could measure until it was too late.

They pushed into Müsterbusch. Buildings and rubble provided concealment. Windows and doorways could hide a Panzerfaust team. Tanks fired high explosive into suspected strongpoints. Infantry cleared houses. The fight became close and brutal.

Pool’s Sherman reached an intersection that offered fields of fire down multiple streets. For a moment, it felt manageable. For a moment, the promise of “home” flickered in the back of Pool’s mind like a light you didn’t trust.

Then a Panther, concealed in a protected position with a perfect line of sight, opened fire.

Two rounds, rapid and precise.

The first struck the turret, penetrated, detonated inside. The second hit the hull almost simultaneously, compounding catastrophic damage.

Inside the turret, Paul Kenneth King died instantly, killed by the violent flash of superheated metal and explosive force. Pool, exposed in the commander’s position as always, was struck by fragments and blast. Shrapnel tore into his right leg. Shock slammed through him.

Even then, instinct fought for command.

“Bail out!”

Richards and Close scrambled out through their hull hatches. Boggs pushed through the loader’s hatch, injured but moving. Pool tried to climb down, but his shattered leg refused to support him. Pain made the world narrow. Smoke thickened. The tank lurched, tipping into a shell crater, and the motion threw Pool partially out, trapping him against the hatch rim.

His crew, already clear, turned back without hesitation.

They grabbed him, pulled him free, dragged him away as ammunition began cooking off in the hull. They got him clear with seconds to spare. Pool stayed conscious, but his right leg was mangled beyond repair. Blood soaked his trouser leg, dark even in the gray morning.

Medics arrived. They stabilized him and moved him back through the chain of evacuation, field hospital to base hospital, then eventually home.

Surgeons amputated his right leg eight inches above the knee to save his life.

War Daddy’s war ended there, on German soil, not with a parade, not with a clean exit, but with the same brutal truth he’d understood since Normandy. Safety was an illusion, and the bill always came due.

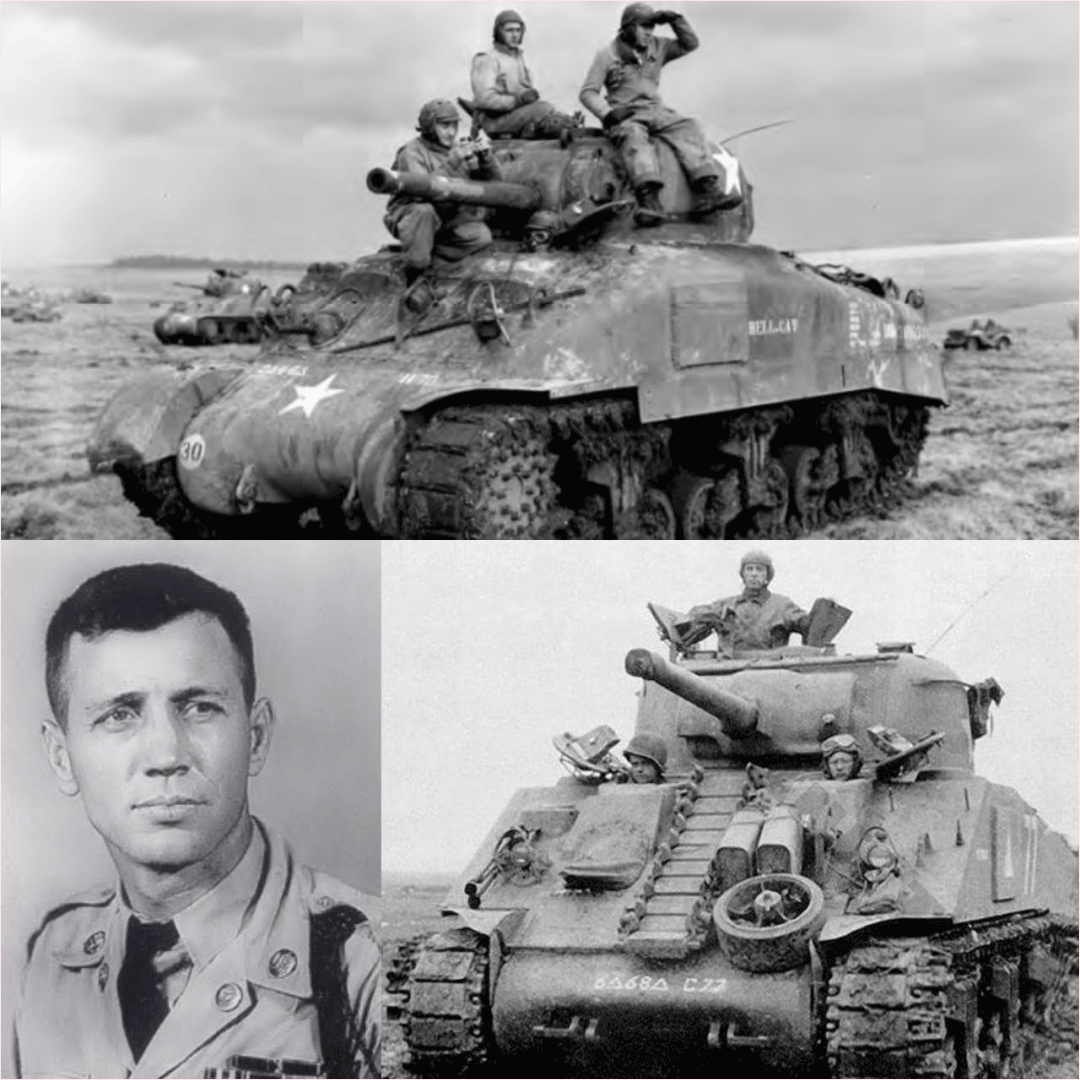

In eighty-three days of combat, from June 29th to September 19th, 1944, Pool and his crew destroyed 258 enemy vehicles, including twelve confirmed tank kills. They killed or wounded over a thousand enemy soldiers, though chaos made exact numbers impossible. They captured around 250 prisoners. They led twenty-one major attacks. They survived three tank losses, the first to a Panzerfaust, the second to friendly fire, the third to a Panther’s aim that finally found its mark.

Pool received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, Belgian honors, and later France’s Legion of Honor as a Chevalier. He was twice nominated for the Medal of Honor. One set of paperwork was reportedly lost in the chaos of war. The other was rejected under reasoning that revealed more about bureaucracy than bravery.

Statistics could not fully explain what had happened. The average Sherman in the European Theater survived about eleven days of combat before being knocked out or destroyed. Pool’s crew survived eighty-three, across three different tanks, continuing to fight after each loss. The average crew destroyed one to three enemy vehicles in an entire combat tour. Pool’s crew destroyed 258.

The secret was never the machine alone. Shermans were outgunned and underarmored compared to Panthers and Tigers. German guns could kill at ranges Americans could not answer. Armor specs favored the enemy.

Pool proved, brutally and repeatedly, that the better crew often won anyway.

Aggression to close range. Tactical intelligence to find flanks and weak points. Drill so tight it became instinct. Leadership from the front. The refusal to retreat when retreat meant giving the enemy time to set the terms.

After he recovered and learned to walk with a prosthetic, Pool could have taken a medical discharge and returned to Texas. Many men would have, and nobody would have blamed them. But the Army had become his life. He reenlisted in July 1948, serving in training and advisory roles, passing on what he learned to new generations of tankers.

He retired on September 19th, 1960, exactly sixteen years after Müsterbusch, as Chief Warrant Officer 2. In retirement he settled near Fort Hood, Texas, remained connected to the armor community, attended reunions, spoke occasionally about his experience. He raised eight children with Evelyn, their marriage enduring through the long echo of war.

Tragedy found the family again when his son, Captain Jerry Lynn Pool Sr., served as a Special Forces officer in Vietnam with MACV-SOG. On March 24th, 1970, a helicopter carrying his team was hit, exploded, and crashed in Cambodia, killing all aboard. His remains were recovered decades later and identified in 2001. He was buried at Arlington with full honors, a son brought home long after the war that took him.

Lafayette Green Pool died May 30th, 1991, in Keene, Texas, seventy-one years old. He was buried with military honors, remembered as one of America’s greatest tank commanders.

At Fort Knox, Kentucky, the home of armor training, a driver training simulator hall was dedicated in his honor. Tankers learned his name the way they learned gunnery tables and radio procedure, as part of the culture of steel and speed and survival.

In 2014, the film Fury reached millions. Its tank commander, War Daddy, drew inspiration from Pool’s story, the essence of a Sherman crew fighting outgunned, relying on training, teamwork, and bold tactics when everything was on the line. Hollywood took liberties, as it always does, but the core truth remained recognizable to anyone who understood what Pool had done.

He was a farm boy from Texas who became something else on European roads.

He proved that specifications are not destiny. That doctrine can be broken. That a crew drilled into one living rhythm can outfight bigger machines. That leadership is not rank, it is action, repeated until it becomes legend.

And he proved, in the hardest way possible, that in war you do not get to choose how it ends, only how you fight while it is happening.

If you want the continuation in the same “American novel polish” style through the remaining sections you pasted, tell me “tiếp” and I’ll continue from this point without changing the format.

News

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

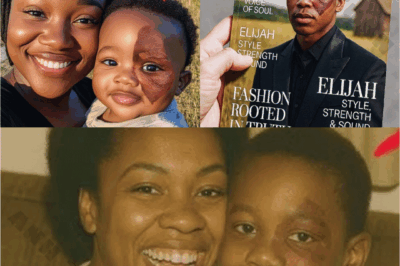

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load