I walked down into the basement and heard them laughing.

“Just leave her down there.”

You’d think a sentence like that would make your knees buckle, or make you cry out, or at least make you angry enough to stomp up the stairs and demand an explanation. That’s what people imagine when they picture betrayal. A single moment, a sharp turn, a dramatic confrontation. But betrayal, real betrayal, doesn’t arrive like a movie. It arrives like dust. It settles in quiet corners and gathers on the small places you stop checking because you’ve lived too long believing your home is a safe thing.

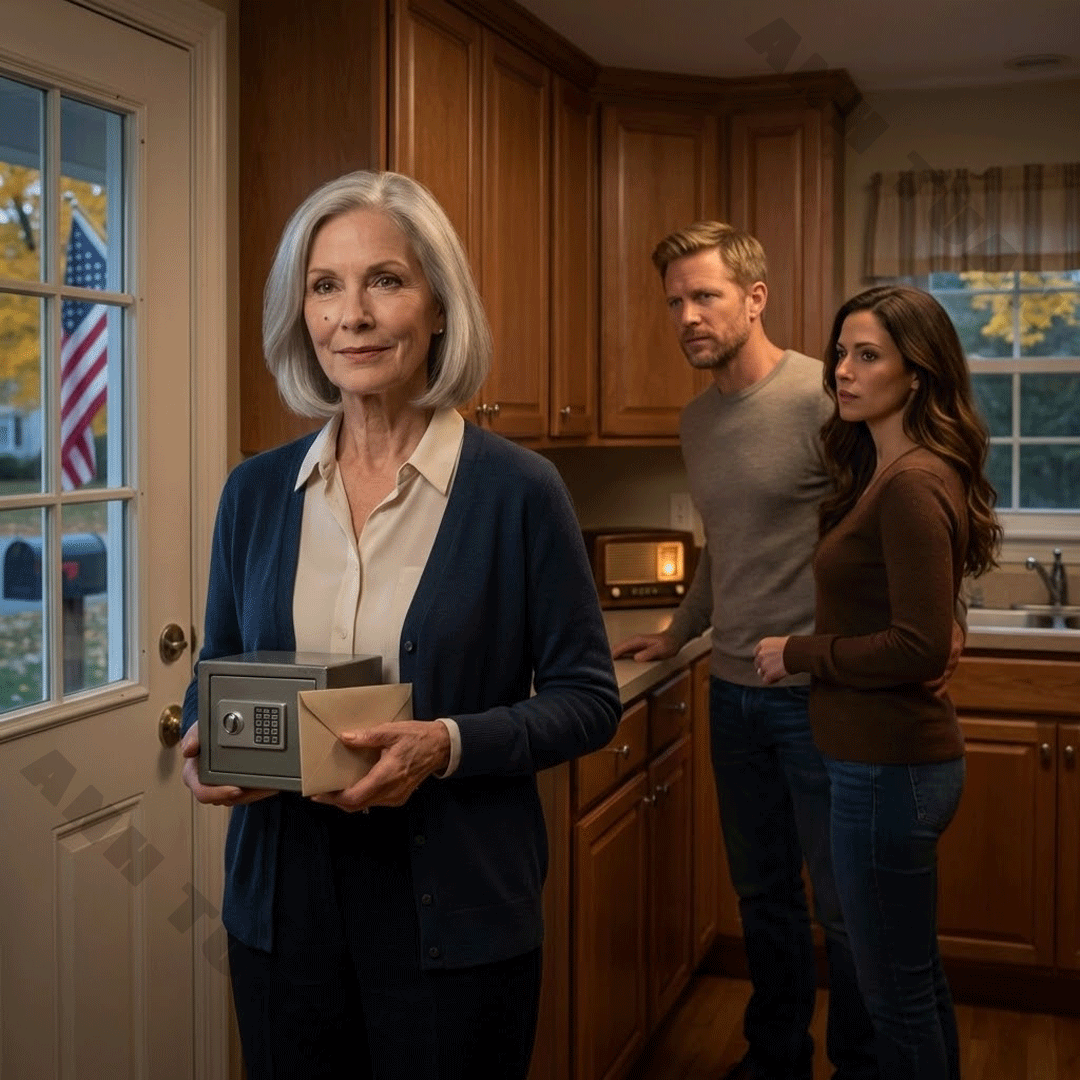

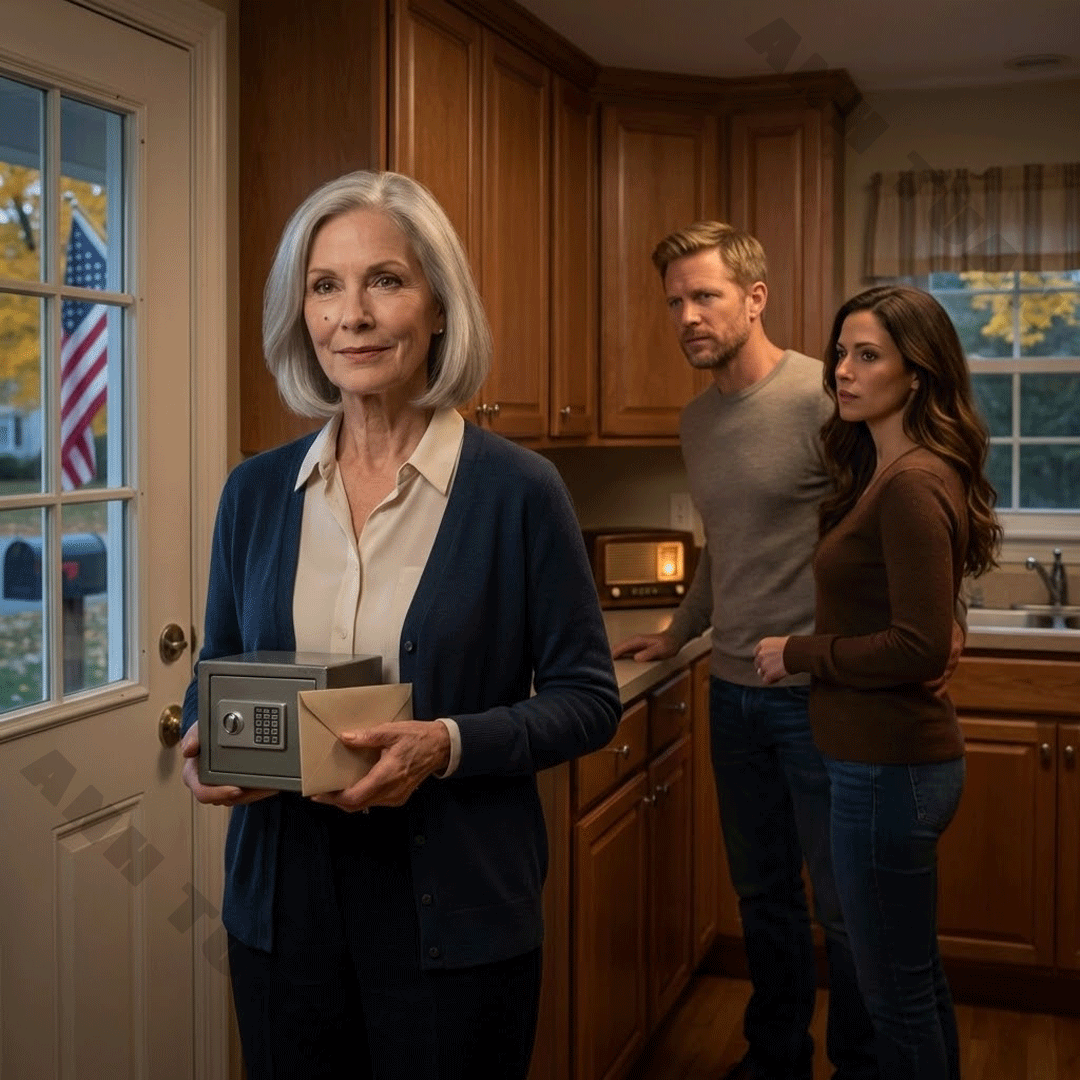

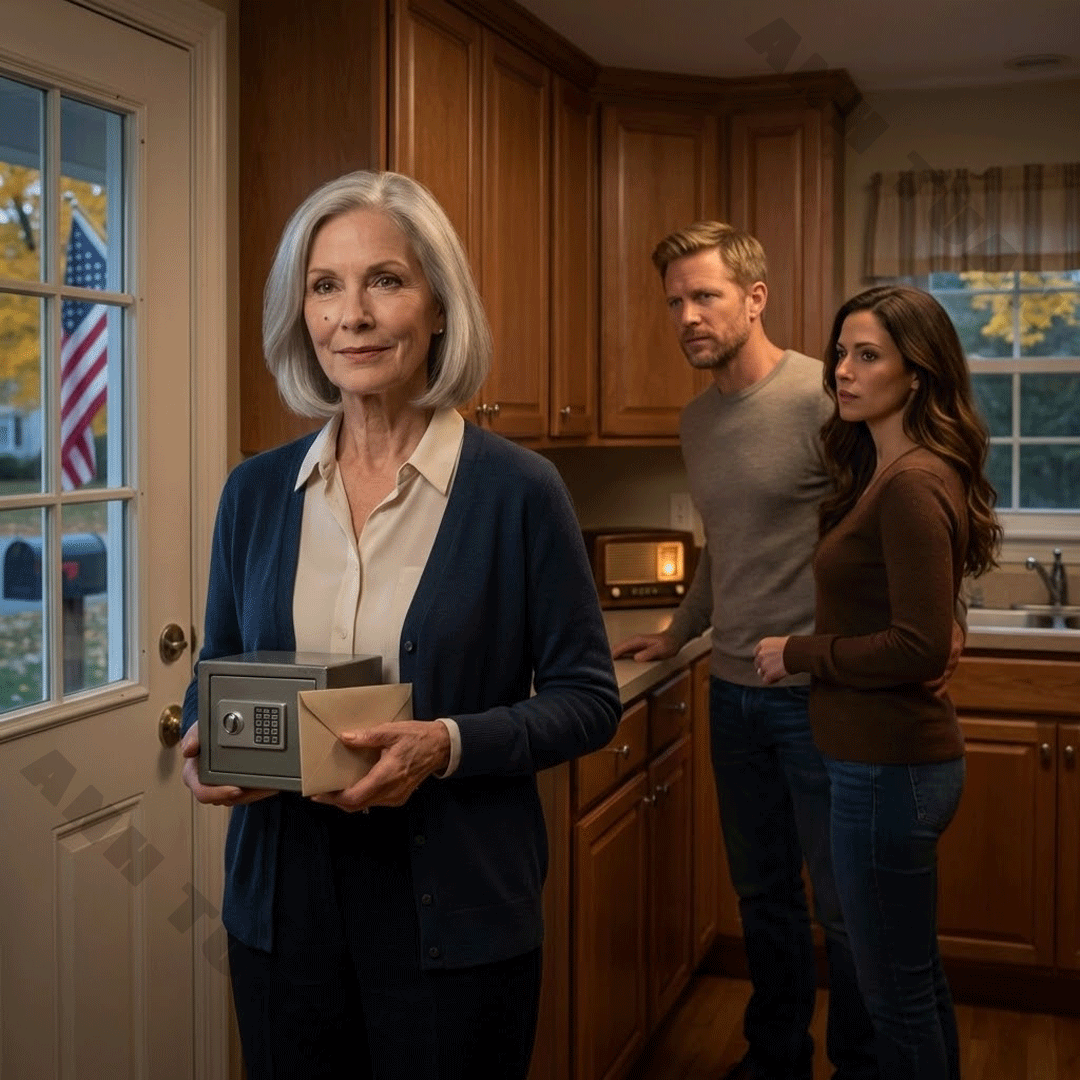

I didn’t react. I didn’t make a sound. I stayed calm, breathed through the tightness in my chest, and let the laughter fade into the ordinary hum of the house. Then I found a way out, and I came back up with the safe they assumed wasn’t mine. They thought they could back me into a corner and control the story, but they forgot one detail that changed everything. By the time they realized something was missing, I was already outside, taking a deep breath, holding the one thing that could set the record straight.

It started earlier than the basement, earlier than the new locks and the doctor’s visit and the way my own kitchen began to feel like someone else’s staged display. It started the first time Carla made a face at my tea.

Not a dramatic face, not something anyone else would have noticed. Just a small wrinkle of her nose and a quick glance toward the open window, as if she was politely asking the universe to ventilate my habits. She was always polite like that, Carla. Polite in the way that makes you feel like you should apologize for existing.

“You still drink it that strong?” she asked, and she tried to laugh as if it was a harmless question.

“It’s tea,” I said, and I kept my voice light because that’s what you do when you want to keep peace in a house that used to be yours.

She smiled, then turned the kettle off with a decisive click, like she could silence something simply by touching a switch.

Carla had been in my life for eight years by then. Eight years of holidays at my table, eight years of folded napkins and politely offered opinions. Eight years of her calling me “Lauren” in public and “Mom” only when she wanted something to sound warm. I had learned the difference between the two versions of her voice. One was for witnesses. The other was for leverage.

Michael, my son, was the kind of man who looked strong until you asked him to stand between two people. Then his shoulders always sloped slightly, as if the weight of conflict made him smaller. When he was a boy, he would cry if his friend got in trouble. When he was a teenager, he would avoid arguments by going quiet. When he married Carla, he brought that same quiet into adulthood and mistook it for kindness.

“Carla’s just particular,” he would tell me when she rearranged my pantry without asking. “She’s trying to help.”

Help is a word that can hold anything inside it. Warmth. Love. Control. Theft. It depends on who’s speaking.

Robert and I built our house the way people built lives in the late sixties and early seventies, not with big dreams and glossy photos, but with steady work and stubbornness. Robert was a millwright at the plant outside town, a man who came home with metal dust on his boots and a laugh that filled the kitchen. I worked part-time at the library when Michael started school, then full-time when money got tight. We lived on paychecks and coupon books and the kind of pride that keeps you from asking for help even when you should.

When we bought the house, it wasn’t charming. It was solid. A two-story colonial with a basement that smelled like earth and old wood. The yard had maples and a slope that made mowing harder than it should have been. The kitchen was small and the cabinets were the color of old honey. But Robert stood on the porch, looked out at the street, and said, “This is it. This is where he’ll grow up.”

Michael grew up there. He scraped his knees on the sidewalk out front, learned to ride a bike on the driveway Robert patched every spring, came in from snowball fights with his cheeks red and his gloves soaked. I kept a jar of pennies on the counter for the ice cream truck and a tin of Band-Aids in the drawer beside the stove. Robert built shelves in the basement for preserves and tools and Christmas decorations, and he built them like he built everything else, as if he expected it to last longer than all of us.

When Robert died, the house didn’t change overnight. It changed the way a room changes when you remove one piece of furniture and suddenly you notice every empty space. His boots stopped being by the door. The sound of his laugh stopped bouncing off the walls. The mornings got quieter. But I stayed. I stayed because the house was my history, because leaving felt like admitting that the life we built could be packed into boxes and reduced to a new address.

At first, Michael visited often. After the funeral, he’d come by on Sundays and eat pot roast and talk about work. Carla came too, always dressed like she was stepping into a photograph. She would compliment the dinner and then suggest small improvements. New curtains. Less clutter. A “more modern” look. She talked about my home the way people talk about a project, and I tried to tell myself it was harmless.

Then Michael got promoted. Then they had their own mortgage. Then Carla started talking about “efficiency” and “future planning,” and Michael began answering my questions with, “Don’t worry about it, Mom.”

It wasn’t one insult. It was a pattern of soft erasures. My mail moved from the table to a side basket in the pantry where I didn’t see it right away. My keys stopped hanging on the hook by the back door and started appearing in a drawer Carla claimed was “more organized.” My checkbook, which I kept in a little box in the kitchen drawer, disappeared for a week and returned with the corners slightly bent, as if someone had thumbed through it quickly and then put it back pretending they hadn’t touched it.

“I’m just trying to make things easier for you,” Carla said when I asked about it.

Michael nodded behind her, like a man agreeing with a weather forecast.

The first time I realized they were talking about me like I wasn’t in the house, it was a bright afternoon in early October. The maples out front were turning gold, the kind of gold that makes you think of old coins and late sunlight. The wind tapped the kitchen window, gentle and polite, as if asking permission to come in. I was at the sink rinsing out a mug when I heard Carla’s voice through the wall just beyond the doorway.

“You’d think she’d want to move,” she said. “Who wants to waste away in a place that smells like old tea and mildew?”

Her voice was clear, sharp, coated in the kind of politeness that always made me feel like a charity case.

Michael replied, low and unsure, but not unsure enough.

“She built her life here.”

Carla sighed, the sound patient and superior.

“We’ll talk to her tonight,” she said. “It’s time.”

My hands were wet. The tea towel crumpled in my fingers. Outside, the leaves moved in the wind like a slow wave. They thought I couldn’t hear, that I was too slow, too soft, too old. They thought the house made me fragile, but they forgot I made the house.

That evening they came with cake. Homemade, too sweet, frosted thick like a cover-up.

Carla sat across from me with that nurse’s smile she’d perfected, the one that made her look like a woman who cared deeply even when she didn’t. Michael hovered behind her, eyes darting like a man trying to escape a conversation he’d already started.

“We were thinking,” Carla said, slicing the cake too neatly, “this house is lovely, but it’s so much work. Maybe it’s time to think about somewhere easier.”

I smiled. The old kind of smile, the kind women wear like armor.

“Is it?” I asked.

Carla’s fork paused. Michael’s shoulders tightened.

“It seems like it’s you who’s tired of visiting,” I said, “not me who’s tired of living here.”

Michael winced. “We only want what’s best,” he mumbled.

I let the silence stretch until it filled the kitchen.

“What’s best?” I repeated. “How generous.”

Carla reached across the table and touched my wrist. Warm hand. Gentle squeeze. The kind of touch people use when they want to look caring while reminding you they can.

“We’ve just been worried,” she said. “About you being alone.”

Alone. As if I hadn’t kept a whole life upright while the foundation cracked beneath me.

The next morning, the plumber came.

A man I’d never seen before, tall and brisk, clean boots, clipboard, the kind of stranger who looked like he belonged in a different neighborhood. He said the water heater needed inspecting. Carla fluttered around him, talking about preventative maintenance. I nodded, but I didn’t miss the way she stood between me and the hallway while he went downstairs.

After he left, the basement door creaked closed and locked.

“Oh, it’s just stuck,” Carla said, laughing too brightly. “Old hinges. We’ll get it fixed tomorrow.”

But I saw the key in her hand. I saw the way she slid it into her pocket like a magician hiding a coin.

That night the house felt different. Not haunted. Claimed.

I sat in my blue chair by the cold fireplace and brewed a single cup of tea. The chair was worn smooth on the arms where my hands had rested for years. Carla once said it made the room feel outdated. She tried to move it into corners the way she tried to move me out of the center of my own life.

I thought about the safe in the basement. Not a dramatic movie safe with alarms and spinning lights. A square iron-gray box built into concrete behind shelving Robert bolted into place the year Michael was born. Robert was the type of man who bought fireproof and wrote down serial numbers. He was also the type of man who never stopped believing the world could shift under your feet without warning.

“It’s not for the money,” he’d told me when he sealed it in. “It’s for what matters.”

I remembered the combination the way I remembered the sound of his laugh.

Right to ten. Left past ten to three. Right to eighteen.

Upstairs, I heard them talking again, soft and urgent.

“She’ll come around,” Carla said. “It’s for her own good.”

Michael said nothing. I knew that silence. I’d heard it when Robert was dying. The kind of silence that meant, Let someone else decide. I’ll just nod.

The next morning the lock on the basement was changed. A keypad now, glossy and new.

Carla offered no explanation beyond a smile and a tap on my shoulder.

“We’re just making a few upgrades,” she said. “Mom, don’t worry.”

She’d started calling me Mom again. The last time she did that was when she wanted money for a sunroom.

I didn’t ask questions. I started counting steps, watching routines, waiting. Not with fear. With clarity. I began noticing the timing of things, the way Carla’s phone calls always happened when Michael wasn’t home, the way my mail disappeared off the table faster than it used to, the way my checkbook stopped being where I left it.

They weren’t trying to help me. They were preparing something. Something they didn’t want me interrupting.

The morning sun slid through the curtains in lines like quiet bars across the kitchen floor. I stayed in bed longer than usual, moving slow on purpose. Let them think I was stiff. Let them think I was fading. It made them careless.

By the time I shuffled into the kitchen, Carla was in yoga pants, scrolling on her phone like it might whisper purpose into her life. Michael stood by the keypad at the top of the basement stairs, tapping something in. He glanced at me, then back at the numbers.

The beep of the lock disengaging sounded too loud in the hush of morning.

I poured my tea slowly. One bag, one sugar, no milk. The same way I’d made it since 1969.

“New lock?” I asked, not looking up.

Michael flinched. “Oh. Yeah. Temporary. For safety.”

“Whose?” I asked.

He didn’t answer.

Carla piped up, cheerful as fresh paint. “There was a break-in down the street last week, remember? It’s just a precaution. We’re keeping tools down there. Don’t want accidents.”

I stirred my tea without drinking it.

“Good to know I’m safer in my own home,” I said.

That afternoon, my keys were gone from the hook. The drawer where I kept the little box of old checks didn’t open. My mail sat in a stack on the counter with the top envelope turned face down, like someone had already decided what I was allowed to see.

That evening, Carla cooked dinner for the first time in weeks. Lemon and herbs and too much salt, served on my good plates. Michael poured wine.

“To your health,” he said.

I watched them over the rim of my glass.

“Did the plumber fix the water heater?” I asked.

Carla smiled too quickly. “Oh, yes. All sorted.”

“Strange,” I said. “I didn’t hear him leave.”

Neither of them spoke.

That night I walked the house in slippers that made no sound, checked windows, doors, the small gaps they forgot to close. The keypad glowed faintly green, like an eye that never slept.

I tried a simple code, not because I thought it would work, but because I wanted to feel the resistance.

Nothing.

In the laundry room, I found a box of my old clothes Carla had “accidentally” packed last winter. She said the attic was too crowded. At the bottom of the box, wrapped in a shawl, was the flashlight I bought after a hurricane knocked out power for three days. Still worked. The beam cut clean and steady across the wall.

I opened the back door and breathed in the night air. Damp leaves. Woodsmoke. A dog barking once and then quiet. Ordinary sounds that reminded me the world was still there, even if my home had started to feel like a staged set.

The next morning they told me the doctor was coming.

“A home visit,” Carla said. “Just to check in. We’ve been worried.”

I lifted an eyebrow. “Worried about what?”

She smiled, tight. “Oh, you know. Memory. Judgment. All that.”

I looked at Michael.

He adjusted the thermostat, busying himself with buttons like they were safer than my eyes.

That’s when the truth landed, heavy and clear.

They weren’t just trying to nudge me into a condo. They were trying to declare me incapable.

I went back to my room and pulled the small suitcase from the closet. Not to pack yet. Just to touch it. Feel the handle. Remember what it meant to have a choice.

I woke before dawn to voices outside my door.

“She’s not going to fight it,” Carla said. “It’s too late for that now. Once Dr. Hill files the assessment, the papers are already halfway done.”

“You sure?” Michael whispered. “She’s still sharp.”

A pause, then Carla’s sigh, patient and superior.

“She’s tired. She’s alone. She needs care. And you need to stop second-guessing everything. Do you want the house or not?”

Silence.

Then Carla laughed, light and cruel at the edges.

“Just keep her comfortable. Lock her down there if we have to. What’s she going to do, climb out a window?”

Their footsteps faded.

I lay still with the blanket heavy over my legs and my breath caught halfway. Lock her down there, like I was a drawer. Like I hadn’t built the shelves and scrubbed the tile and paid every tax bill for decades.

By the time I rose, the house had shifted back into its morning performance. Bacon on the stove. Local news low. Carla humming out of tune.

I stepped into the kitchen.

“Morning, Mom,” Carla said, bright as an infomercial. “We were thinking. Could you help us sort boxes downstairs today? Just the old ones. Michael’s back’s been acting up.”

I looked at her long enough to let her feel the weight of my attention.

“Sure,” I said.

Carla’s smile widened like I’d passed a test she didn’t know I was grading. Michael avoided my eyes.

Carla handed me the flashlight. “Just until we get a bulb fixed.”

That bulb worked yesterday.

I walked to the basement door and waited. Carla typed the code into the keypad with easy confidence.

4-6-2-2.

The door clicked.

I stepped inside.

The basement smelled of earth and rain and old wood, an honest smell that didn’t pretend. The flashlight beam swept across the workbench, the shelves where I once lined jars of peach preserves like soldiers, the bins of decorations stacked because memory is heavier than trash.

I let the door close behind me.

The click sounded louder than it should have.

I didn’t rush. Rushing makes noise. Rushing makes mistakes. I walked deeper, toward the far wall where Robert’s shelving stood. The flashlight flickered once. I tapped it and steadied the beam.

The safe was still there. Old square iron gray, half covered by a yellowed sheet.

I knelt slowly. My knees groaned, but my hands didn’t shake. The dial was cold under my fingertips, familiar as a wedding ring.

Right to ten. Left past ten to three. Right to eighteen.

The hinges resisted, then gave. The door opened with a soft groan that felt like a secret being released.

Inside, the envelope sat exactly where it had always been. The one Robert tucked in the day he told me, quietly, that love sometimes meant planning for the worst even when you didn’t want to believe it could happen.

I pulled it out and opened it carefully.

A bank statement from a private account I hadn’t touched in years. The deed to the house with my name alone printed clean and undeniable. Our marriage license. Insurance papers. A note from Robert in his handwriting.

If they forget who you are, remind them.

Beneath it all, in a small leather pouch, the key to a deposit box no one but me knew about.

Above me, footsteps moved across the kitchen floor, muffled and careless. Carla laughed again, louder than necessary, the sound of someone who believed the room she locked was the room that mattered.

I looked around the basement and saw what they never bothered to see.

Not junk. Preparation.

A fireproof lockbox behind a cabinet. Envelopes labeled in Robert’s tidy hand. A rusted biscuit tin in the corner that I suddenly remembered, the one Robert used to tease me about because I kept it even after the biscuits were gone.

I opened it.

Keys. Old keys. Church. Shed. Car. And one brass key I didn’t recognize.

Taped to the inside lid was a slip of paper.

P.O. Box 119. Still active. Keep the lease paid. R.

My throat tightened, not with sadness, with the shock of being understood across time. Robert didn’t just leave me memories. He left me exits.

The flashlight dimmed slightly. I flipped the batteries, squeezing out more life the way you do when you’ve lived through storms and outages and decades of making do.

Then I heard it.

The lock.

A sharper click, followed by the solid sound of something sealing.

Carla.

They were doing it. They were locking me in.

I didn’t panic. Panic is what they wanted. Panic makes you look incompetent. Panic makes their story easier to sell. I stood, slow and steady, and began packing like a woman who had packed school lunches and emergency kits and holiday meals for half a century.

The deed. The bank statement. Robert’s note. The brass key. The deposit box key. The cash tin I found beneath a tarp, heavier than it had any right to be. A flip phone tucked away in an old shoebox, half charged, screen glowing to life with Robert’s crooked smile on the wallpaper.

Always just in case, he’d called it.

Always.

I pulled the suitcase close, laid it open on the folding table, and stacked everything neatly. Neat is its own kind of defiance. Neat says you are thinking. Neat says you are not lost.

Then I turned toward the basement window.

It was half hidden behind old screens and vines, the kind of window people forget because it isn’t convenient. Carla forgot it because Carla didn’t look for inconvenient truths. Michael forgot it because Michael forgot anything that required courage.

But I didn’t forget.

I set the suitcase beneath the window and pulled the old step stool Robert built when I was pregnant, his initials carved beneath the paint. I climbed, not fast, not shaky, just steady.

The latch still worked. The frame groaned when I pushed it open, swollen from age and weather, but not locked.

They never secured what they didn’t value.

Cold air hit my face, sharp and clean. I realized in that instant how stale the house had become, or maybe how stale my place in it had been made.

I eased the suitcase through first. It dropped into the mulch with a dull thud. Then I followed, one leg out, then the other, palms gripping the stone edge like I was climbing back into myself.

The yard was still. A dog barked once in the distance. Inside the house, warm light glowed behind curtains.

They wouldn’t notice right away.

They would assume I wandered.

They would assume confusion.

They would underestimate me one last time.

I crouched behind bushes, pulled my coat tight, and moved along the side of the house toward the garage. Branches brushed my sleeve. Gravel crunched under my shoes, loud enough to make me pause and hold my breath until the sound dissolved into night.

The porch light glowed through the kitchen window. Carla’s silhouette moved past the sink, smooth and unhurried, like she was already rehearsing her version of the morning.

I crouched beside the garage side door and slid my fingers under the ceramic frog Robert bought as a joke. Ugly thing, chipped now, loyal as a witness.

Still there.

The key sat cold against my skin like a promise kept.

The lock turned with a soft click. I slipped inside.

The garage smelled like oil and old wood and dried grass clippings. Robert’s workbench still sat against the wall, tools hanging where he left them. Carla once suggested turning it into a home gym, bright and airy, like you could sweat your way into a different personality.

Under a tarp in the corner was my old bicycle, scuffed paint, sturdy frame, the one Robert tuned up every spring. I didn’t need it tonight, but seeing it steadied something in me. Proof I used to go places on my own.

I opened the cabinet above the workbench. The door stuck, like it always had. Inside sat the fireproof box Robert called “the boring one,” as if boring wasn’t what saved you when people started making your life into a narrative.

I lifted it down, snapped it open, and found what I needed: birth certificate, Robert’s death certificate, old titles, tax records, and a business card in a plastic sleeve.

Whitaker & Lowry.

“You’ll know if you ever need him,” Robert had said years ago when he brought that card home.

I slid the card into my pocket and closed the box.

I shut the cabinet, lowered the tarp back over the bike, and eased the garage door shut behind me. Then I walked down the driveway like any neighbor taking a late stroll. No rush. No drama. People notice what looks guilty. They ignore what looks routine.

At the corner, a streetlamp cast a pale circle of light on cracked sidewalk. I stepped into it and turned back once.

The house stood quiet. Curtains drawn. Warm squares of light in the windows. The porch where Robert used to sit with coffee in summer, cicadas loud enough to drown out anything we didn’t want to talk about.

Something pinched behind my ribs. Not regret. Recognition. The house had held so much of me that leaving it felt like leaving a body. But it hadn’t been mine lately. A home is supposed to keep you, not contain you.

A cab drifted through the neighborhood like a small mercy. I lifted my hand once. The driver pulled over.

“Where to?” he asked.

I gave him an address without hesitation. A motel near the train station in the next town over, the kind with paper-thin walls and a blinking neon sign, a place people passed through without leaving fingerprints on the future.

He didn’t ask questions. That’s another thing America does well sometimes. It lets you move without being interrogated, as long as you don’t look like trouble.

At the motel, the neon sign buzzed overhead, red and tired. The lobby smelled like lemon cleaner and old carpet. A small TV behind the desk played the news with the volume low. A talking head’s mouth moved silently like the world was always speaking and no one was listening.

I paid in cash. No names. No card. Just a nod.

The clerk slid me a key without looking up. “Room twelve,” she said like she’d said it a thousand times.

My room was exactly what I expected. One bed. Thin blanket. A lamp that buzzed faintly when I turned it on. A heater unit in the wall that rattled like it resented working. Pale yellow curtains, sun-faded like an old photograph.

It was perfect.

I set the suitcase on the bed and opened it, laying everything out with the care of a woman who had spent years keeping order when order was the only thing she could control.

The deed. The bank statements. Robert’s note. The deposit box key. The brass P.O. box key. The cash tin. The fireproof box documents. The old flip phone.

I picked up the business card and traced the letters with my thumb.

Whitaker & Lowry.

I dialed.

It rang three times.

“Whitaker & Lowry,” a receptionist answered, voice trained to be calm around heavy things.

“I need to speak with Mr. Whitaker,” I said.

“May I ask who’s calling?”

I took a slow breath, not because I was unsure, because I was choosing the moment.

“Tell him it’s Lauren Blakeley,” I said. “Robert Blakeley’s widow. He’ll remember.”

A pause. Typing. Then, “Please hold.”

Soft music filled the line, instrumental and bland. I stared at the motel wallpaper, tiny flowers that didn’t quite line up at the seams, and felt the first true wave of exhaustion wash through me. Not weakness. The body catching up to what the mind had already done.

When Whitaker came on, his voice sounded older than I remembered, but still precise.

“Mrs. Blakeley.”

Not surprised. Not rushed. As if he’d been expecting my call for years and had simply been patient enough to wait.

“I’m ready,” I said. “I’m ready to change everything.”

He asked practical questions. Where I was. Whether I was safe. Whether I had documents. Whether anyone had threatened me.

He didn’t ask if I was confused. He didn’t speak to me like I was fragile. He spoke to me like I was a client, which is another way of saying a person with rights.

We set a time. Noon tomorrow.

“Bring everything you have,” he said. “And do not go back alone.”

“I won’t,” I said, and realized I meant it in more ways than one.

After I hung up, the dial tone filled the room like a long exhale. The heater rattled to life on its own, as if the room sensed I was cold.

I brewed tea using the motel coffee maker. The water tasted faintly of old grounds, but I didn’t care. I wanted something warm in my hands. Steam curled into the air, and for a moment the room felt less like hiding and more like a threshold.

That night I slept in short pieces. Not from fear. From adrenaline and age and the unfamiliar feeling of being in motion again. Each time I woke, the lamp cast a weak circle of light over the room and I saw my suitcase and remembered: I did it. I chose.

In the morning, I washed my face in the tiny bathroom sink and looked at myself in harsh light. Lines around my mouth. Tiredness under my eyes. Gray in my hair Carla liked to comment on like it was a problem she could solve.

But my eyes were steady.

At Whitaker’s office, the building looked like it had been standing longer than most of the people inside it. Dark brick. Brass plate by the door. Hallways that smelled like old paper and furniture polish.

Whitaker met me himself. He shook my hand like I was important, then guided me into his office and shut the door softly.

He laid my documents out across his desk like evidence.

“I reviewed what you sent,” he said. “The title is clean. Your ownership is indisputable.”

I nodded. “Robert made sure of that.”

“Smart man,” Whitaker said, and there was no pity in it. Just fact.

He spoke about a revocable trust, transfer of assets, a new will, a statement of capacity. He explained consequences the way he explained weather. Calm. Clear. Unemotional. Not because he didn’t care, because emotion wasn’t what kept you safe in courtrooms and banks.

“And your son,” he said carefully, “what do you want?”

The question landed heavier than I expected. Not because I didn’t know the answer, because saying it out loud made it real.

“I want him to have no claim,” I said. “I want the house and everything tied to it protected.”

Whitaker didn’t flinch.

“Then we do it,” he said.

When it came time to sign, I took the pen and felt the weight of it. Each signature felt like laying a stone in a new path, one I built myself. The way Robert and I used to fix the garden wall, brick by honest brick, no rush, no cracks.

After, Whitaker slid another folder toward me.

“This is your statement of capacity,” he said. “In case anyone tries to challenge what you’ve done. I had Dr. Meyers review your records.”

I lifted an eyebrow. “Carla said a doctor was coming.”

Whitaker’s mouth tightened slightly. “She may try. But you’re documented.”

I left Whitaker’s office with a thick envelope and a strange kind of calm. Not relief. Clarity.

I still needed somewhere to go. Somewhere that wasn’t a motel with buzzing lights. Somewhere that wasn’t my house.

I called Eloise from the flip phone that afternoon. Eloise was my oldest friend, the one who knew me before I was anyone’s mother-in-law, the one who lived two states over and once said, half joking, “If you ever need to disappear for a while, my guest room has your name on it.”

When she answered, her voice was warm with surprise and caution.

“Lauren?”

“I’m cashing in that offer,” I said. “Do you still have the guest room?”

A pause, then, “Of course I do. And I just made chili.”

We laughed, and the sound felt like something I hadn’t used in years.

That night I sent one message from the flip phone to Michael and Carla, not to negotiate, to clarify.

I’m safe. I left voluntarily. Do not file a report. Do not contact my bank. Do not contact my lawyer. Everything you left locked behind you is exactly where you left it, except the money, the house, and me.

Then I turned the phone off.

I didn’t need to hear their panic. I needed to keep my mind clean.

Two days later I boarded a train with a one-way ticket and a suitcase that held more than clothes. It held paper. It held proof. It held my voice in forms the law respected.

At the station, no one looked at me. That was the best part. I wasn’t Mom. I wasn’t Nana. I wasn’t that poor old woman Carla described like a burden. I was just a woman with a suitcase going somewhere she chose.

Eloise met me at her station with headlights bright and jaw set, the face of a woman who had already decided she wouldn’t let anyone shrink her friend again. She didn’t hover. She didn’t ask for a dramatic retelling. She took my suitcase like it weighed nothing and asked if I’d eaten.

Her guest room smelled like rosemary and old books. Fresh sheets. A small lamp glowing in the corner. A window facing east. A quiet that didn’t feel like a trap.

“You can stay as long as you want,” she said. “Or as little.”

I nodded, too tired to answer.

That night, I placed Robert’s letter on the bedside table beside a small ceramic bluebird I’d carried wrapped in a dish towel. Carla called it tacky. Robert gave it to me the day we moved in, said it was a symbol of peace, but only the kind you earn.

I slept without waking, not because I was safe, because I knew I was the one making decisions again.

The next morning, Eloise slid a spiral notebook across the kitchen table.

“Write down everything you remember,” she said. “Facts. Dates. What was said. Who was there.”

I stared at the notebook, surprised by how quickly my mind obeyed. For months, Carla had tried to train me to doubt my memory. Eloise treated my memory like a tool.

“I can do that,” I said.

“I know,” she replied.

We spent the day organizing. Eloise drove me to buy folders, labels, a cheap scanner. We spread documents on the guest bed like a puzzle. Deed. Bank statements. Robert’s note. Keys. Insurance. The capacity statement. My handwritten timeline. Carla’s keypad code.

Whitaker called and spoke to Eloise directly, not because he didn’t trust me, because he understood what it looked like when people tried to paint you as unstable.

“She’s staying with me,” Eloise said. “She’s safe. She’s clear. She’s not confused, and she’s not alone.”

Whitaker’s voice softened slightly. “Good.”

The next day we went to the bank for the deposit box. The manager led us to the vault. The air inside felt cooler, like money and secrets had their own climate. I slid the key in and opened the box with hands that didn’t tremble.

Inside was Robert’s mind, not just papers, plans. Original copies of title paperwork. Account numbers in his handwriting. A sealed envelope labeled FOR LAUREN ONLY. A note tucked under a second key.

If you’re here, you already know why. Don’t hesitate. Call Whitaker. Call Eloise. Say it out loud.

I swallowed hard. Robert didn’t know Eloise would be the one, not specifically, but he knew I’d need someone.

We scanned everything. We made duplicates. We labeled folders. Paper against fog.

Back at Eloise’s, my phone buzzed with missed calls I didn’t answer. Michael’s voice left voicemails calling me confused, calling me lost, calling me back.

Confused was the only version of me that made his choices feel forgivable.

I deleted the messages without listening.

Two days after the guardianship petition was dismissed, another envelope arrived. County Court. My name printed cleanly.

Michael had filed again, this time with different language, different framing. Diminished capacity. Safety. Concern.

Eloise read it and went still.

“They’re trying to take your legal voice,” she said.

“Yes,” I replied.

Eloise looked at me hard. “Call Whitaker.”

Whitaker answered like he’d expected it.

“Do not contact your son,” he said. “Do not respond in writing to anything they send. You will come to my office today. Bring the notice. Bring everything.”

We went. Whitaker filed objections. He prepared exhibits. He treated their attempt like what it was: a move. Not a verdict.

At the courthouse, Carla arrived dressed like the picture of concerned care, beige coat, hair neat, eyes soft for witnesses. Michael stood beside her like a man trying to disappear into his own shame.

Carla tried to speak to me in the hallway.

“Lauren,” she said in that careful voice meant to make her look reasonable.

Whitaker stepped between us politely.

“Mrs. Blakeley will not be speaking with you outside court,” he said.

Carla blinked, and for a fraction of a second her composure cracked.

Inside, Carla’s attorney used soft language. Concern. Best interest. Safety. Whitaker used paper. Title. Trust filings. Capacity statement. Documented intent. Witnessed signatures. Evidence of restricted access.

The judge, an older woman with glasses and a face that had seen every kind of family claim, asked me a simple question.

“Do you wish to have a guardian appointed over you?”

“No,” I said.

“Why did you leave your home?” she asked.

“Because my access to parts of my home was being restricted,” I said. “Because my keys and mail were moved without my consent. And because I learned plans were being made to declare me incapable without my agreement.”

Carla’s attorney tried to interrupt. The judge shut him down with a raised hand.

Whitaker submitted evidence. Receipts from the locksmith showing Carla paid for the keypad. My timeline. The capacity statement. The trust records.

Michael was asked if he personally observed confusion that rose to incapacity.

He hesitated, as always.

“No,” he admitted.

The judge dismissed the petition. She noted in the record that further attempts without substantial evidence could be viewed as harassment.

In the hallway afterward, Michael tried to speak.

“Mom, please ”

I looked at him without trying to save him from his shame.

“You filed papers to take my voice,” I said. “You don’t get to call that love.”

Carla tried to step in with her performance.

“We were trying to help.”

Eloise spoke quietly.

“Help doesn’t need a judge.”

After that, Carla shifted tactics. A report to Adult Protective Services. Anonymous, of course. Alleging confusion and undue influence. The goal wasn’t truth. The goal was to create files. Files create doubt. Doubt creates leverage.

Whitaker told us to welcome the investigation and offer documentation. Eloise and I prepared a clean folder with everything: capacity confirmation, trust documents, evidence of independent travel, receipts, timeline, witness statements. We made it easy for the truth to stand up on its own.

Then Whitaker said the thing I didn’t want to hear, but needed to.

“The house,” he said. “They’re still living there. That’s leverage. They can dispose of property. They can claim abandonment. They can reshape the space to match their story.”

My chest tightened.

“We send formal notice,” he said. “We demand preservation. We schedule a supervised retrieval of your personal items. And we change the locks. If they refuse, we proceed legally.”

A part of me wanted to say I didn’t care about the house. That walls were walls. But I knew Carla didn’t just want my absence. She wanted my erasure to look natural.

“Do it,” I said.

The supervised visit came on a gray Tuesday. Whitaker arranged a sheriff’s deputy to meet us at my house. Not for spectacle. For structure. Carla respected authority only when it came with uniforms.

When we pulled onto my street, the houses looked the same. Trimmed lawns. Holiday wreaths still up because people hadn’t gotten around to taking them down. Familiarity hit like seeing an old photograph you couldn’t climb back into.

The deputy stood by his cruiser, polite, uncurious.

“Mrs. Blakeley?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

He nodded toward my front door.

“Your attorney is inside,” he said. “The occupants are aware.”

Occupants.

Not family. Not caregivers. Occupants.

Whitaker opened the door and stepped aside like a man escorting a rightful owner back into her own space.

The house smelled different. Less like tea and old books, more like Carla’s lavender cleaner, sharp and false, determined to erase history. The living room had been rearranged. My blue chair was shoved into a corner turned away from the window. Beige throw pillows replaced the ones I’d sewn years ago.

Carla stood near the kitchen doorway, hands clasped, posture perfect.

“Lauren,” she said softly, as if she were speaking to a toddler.

I didn’t answer.

Whitaker spoke politely.

“We are here to retrieve Mrs. Blakeley’s personal items as stated. The deputy is present to ensure the process remains orderly.”

Carla’s smile tightened. “I just want what’s best for her.”

The deputy’s expression didn’t change.

“Ma’am, we’re not here to discuss what’s best. We’re here to keep the peace.”

Michael hovered behind Carla, eyes tired and red.

“Mom,” he said quietly.

I held his gaze.

“You used a court to try to take my voice,” I said. “Don’t ask me to comfort you now.”

Whitaker handed me the list we prepared. Room by room. Item by item. No explaining.

I walked through my own house like a visitor.

The hallway photos were missing, not thrown away, moved into a box by the coat closet. Carla had been careful. Careful meant she wanted plausible deniability.

In my bedroom, the drawer where my jewelry box belonged was half empty. My winter coat was gone. My good scarf, too. The bottom drawer where I kept Robert’s service papers and old tax returns was stripped.

Carla didn’t take them for sentiment. She took them for leverage.

Eloise stepped into the doorway behind me and went still.

“She took them,” Eloise said.

I nodded once.

Whitaker’s voice stayed calm. “We’ll address that.”

In the kitchen, my old tea tins were gone. Carla replaced them with matching clear jars like a magazine layout. She’d turned my kitchen into a showroom. The emptiness of it made something in me go cold.

In the basement, the keypad still gleamed.

The deputy looked at Carla.

“Ma’am, provide the code.”

Carla’s chin lifted. “I don’t see why ”

Whitaker’s voice stayed mild.

“Because you were notified. Because it is her property. Because refusing will be noted.”

Carla recited the code like a prayer she didn’t believe in.

4-6-2-2.

The lock beeped. The door opened. The basement smelled of earth and rain and old wood, the foundation’s honest breath. The sheet over the safe had been pulled aside.

Carla had been down here.

She just hadn’t known what she was looking at.

Michael came down one step and stopped like the basement itself made him uncomfortable.

“Mom,” he started.

I turned toward him.

“You stood upstairs while they locked this door,” I said.

“I didn’t ” he began.

“You didn’t stop it,” I corrected. “That’s what matters.”

Carla laughed too brightly.

“She’s exaggerating. Old houses stick. Doors stick.”

The deputy glanced at Whitaker, then at me.

Whitaker looked at me. “Would you like to make a statement for the record regarding access restrictions?”

“Yes,” I said.

Back upstairs at the kitchen table, the deputy took notes as Whitaker asked questions to build a clean record. Denied access, keys removed, mail withheld, consent not given, pressure applied. Carla tried to interrupt. The deputy shut her down calmly.

When it was done, the deputy handed Whitaker a copy.

Whitaker said, “Mrs. Blakeley will be changing locks and codes. The occupants will be given formal notice of next steps.”

Carla’s composure shattered for a fraction of a second.

“You can’t,” she snapped.

Whitaker’s eyes stayed calm. “We can. And we will.”

Michael’s voice broke.

“Mom, where are we supposed to go?”

I looked at him and felt the ache flare because he was still my son, but being a mother didn’t mean being a doormat.

“That,” I said quietly, “is what you should have thought about before you tried to make me disappear legally.”

Eloise stood near the sink, arms crossed, watching Carla like a person watches a snake. She didn’t yell. She didn’t perform.

She simply existed as a witness.

I took what I wanted, not what looked valuable, what was mine in the only way that matters. Robert’s army tags. The photo of us on the front steps. My recipe box thick with cards in my handwriting. My mother’s quilt from the cedar chest. The ceramic bluebird wrapped carefully in a towel.

I stopped in the living room and placed my hand on the arm of my blue chair. Worn smooth by years of evenings, grief, patience. I didn’t take it. Not because I didn’t want it, because I didn’t want to drag my old waiting place into my new life.

I walked out without looking back at Carla’s face.

Outside, the air hit cold and clean. Wind chimes tinkled. A car passed, tires hissing on pavement. The world kept going, indifferent and wide.

In Eloise’s car, my suitcase felt heavier, not with objects, with closure.

Whitaker filed notices. Locks were changed. Codes reset. Carla and Michael were ordered to vacate. Carla tried to cry to neighbors, to church friends, to anyone who would hold her performance for her, but paper doesn’t care about performance.

The notice on the door was white and clean and unfeeling. Carla stood on the porch and cried for an audience. Michael stood behind her with hands in pockets and eyes on the ground.

They moved out within the week.

When Eloise told me, she didn’t sound triumphant. She sounded relieved.

“Locks changed,” she said. “They’re out.”

I sat with my tea and let the words settle.

Out.

The house was empty now, not of memory, of their hands. The air could rest. The walls could stop holding whispers.

“We sell it,” I said. “And we use it.”

Whitaker listed it. Offers came. We accepted one that was reasonable. The inspection happened. The closing went through. The house that had been my life became fuel.

Whitaker transferred the funds into the trust. The shelter received the first wire.

The director called me.

“I wanted you to hear it from me,” she said. “The funds cleared.”

I sat in Eloise’s guest room with morning light spilling across the quilt and felt something loosen in my chest.

“Use it for doors,” I said. “Use it for beds. Use it for the quiet things that keep someone alive.”

“We will,” she promised.

Whitaker asked if I wanted my message printed in the classified section like we’d discussed.

“Once it’s in print,” he said, “it can’t be pulled back.”

“That’s the point,” I replied.

On Thursday, Eloise brought the paper in from the porch and set it on the table. The bundle made a soft thud against wood. Ordinary and heavy.

I flipped pages until I found it. A block of text. No headline. No drama. Just words that didn’t beg, signed Lauren B.

I didn’t name Carla. I didn’t name Michael. I didn’t list the keypad code or the basement window or the safe. I wrote about the slow eraser, the way people fold your life inward and call it care. I wrote that old women are not relics, not children, not yours to arrange. I wrote that silence isn’t safety, it’s surrender, and that sometimes peace isn’t quiet, it’s a notarized form and a packed suitcase and a door you open yourself.

After it ran, Whitaker called.

“People are asking,” he said. “They’re asking what to do if their kids started helping too much. They’re asking how to protect themselves.”

“Tell them to write it down,” I said. “Tell them to keep their papers. Tell them to notice.”

Weeks passed. Then months. Winter turned to a thinner kind of cold, then to the first signs of spring, the kind that arrives with muddy lawns and stubborn green shoots. Eloise drove me to the shelter every Thursday. The building smelled like coffee and laundry detergent and tired hope. I sat with women in intake rooms, listened to stories that weren’t mine and still felt familiar because being made small has a language.

One woman, maybe thirty, asked me why I did it, why I didn’t just let them win.

“Because they didn’t ask,” I told her. “They assumed.”

She nodded slowly, then hugged me tight enough I nearly lost my balance.

It wasn’t recognition I wanted. It wasn’t revenge. It was air. Air for women locked in rooms, in basements, in marriages, in silences. Air for women told to shrink because someone else wanted the space.

Carla never apologized. Michael wrote one letter that Whitaker advised me not to answer. It was full of regret shaped like self-pity. He said he was sorry things went so far. He said he felt lost. He said Carla was only trying to help. He still couldn’t say the real words. I locked you out of your own life. I let her do it. I wanted the house.

I put the letter in a folder and filed it away. Not because I needed it emotionally, because paper has a way of becoming useful when people try to rewrite history again.

One afternoon in early spring, Eloise and I sat on her porch with tea. The air smelled like damp earth and new leaves. A neighbor’s dog barked at nothing. Wind moved through the trees like a soft exhale.

“You miss it?” Eloise asked, nodding toward the direction of my old town as if distance had direction.

I thought about the porch steps, the maple tree Robert planted, the crack in the driveway roots lifted because roots don’t ask permission. I thought about my blue chair, how it used to face the window until Carla turned it away.

“No,” I said, surprising myself with how true it felt. “I miss pieces. Not the trap.”

Eloise watched me over the rim of her mug.

“You know what they’ll say,” she said. “They’ll tell people you were influenced. They’ll tell people you were confused. They’ll tell people you ran.”

“I know,” I said.

“And you?” she asked.

I looked at my hands, the same hands that kneaded bread and patched clothes and signed papers that changed everything. The same hands that gripped the stone edge of a basement window and pulled me back into air.

“I didn’t run,” I said. “I walked out.”

Eloise nodded like she’d been waiting to hear that sentence.

That night, in the guest room, I opened my notebook and wrote one line at the bottom of the page marked AFTER.

This is not revenge. This is release.

Then I turned the page and wrote the next thing, not because I was documenting a war anymore, because I was building a life.

I wrote about the way tea tastes when no one is making faces at it. I wrote about the way morning light falls in a room where you decide who enters. I wrote about the shelter’s new wing and the simple plaque by the door that would read, For those who were told to shrink, may you always expand instead. I wrote about Robert, how he used to say paper speaks louder than memories, and how right he was, and how love sometimes looks like a safe built into concrete and a key hidden inside a biscuit tin.

I wrote about the basement, too, but not as a place of fear. As a place of truth. The foundation doesn’t lie. It holds.

They locked the door, but I still had the key.

And I used it.

The first time the doorbell rang at Eloise’s after everything went on record, I felt my shoulders lift before I could stop them. My body remembered surprise as danger. It remembered how quickly a normal morning could become a trap with a smile and a clipboard. Eloise, hearing the chime from the kitchen, didn’t flinch. She wiped her hands on a dish towel and walked to the front door like a woman who didn’t ask permission to meet the world.

“Who is it?” I called, more out of habit than fear.

Eloise looked through the peephole and answered without turning around.

“Adult Protective Services,” she said.

The words landed soft and heavy at the same time, like a blanket dropped over a sleeping person. I stood up slowly from the table, tea cooling beside my notebook. For a second, my mind tried to jump ahead into the version of the story Carla wanted, the one where a stranger in a blazer would see my age and my suitcase and decide I must be confused. That’s how fear works. It writes the ending before you even speak.

Whitaker’s voice came back to me, calm and steady.

Welcome it. Facts. Paper. Consistency.

Eloise opened the door.

A woman stood on the porch with a county badge clipped to her cardigan and a folder held neatly against her chest. She looked to be in her late forties, hair pulled back, sensible shoes, eyes that didn’t dart. She wasn’t dramatic. She wasn’t suspicious. She looked tired in the way people look when their job involves listening to other people’s worst days without being allowed to carry any of it home.

“Ms. Kline,” she said, holding out an ID. “I’m with APS. Are you Mrs. Blakeley?”

“Yes,” I said, stepping into the doorway.

Her gaze moved over me once, not assessing my wrinkles, not counting my years, just registering a person in front of her.

“May I come in?” she asked.

Eloise stepped aside. “Of course.”

Ms. Kline walked in and glanced around the living room, the hallway, the kitchen beyond, as if checking for obvious danger. She wasn’t sniffing for secrets. She was doing the job she was supposed to do. That alone made my chest loosen slightly. I hadn’t realized how much I needed someone neutral to exist in this situation, someone who didn’t belong to Carla’s performance or Michael’s guilt.

We sat at the kitchen table. Eloise poured coffee for herself and offered tea for me out of habit, then remembered and asked Ms. Kline.

“No, thank you,” Ms. Kline said. “I’m fine.”

Her folder opened with a quiet rustle.

“I received a report,” she began, voice even, “that you may be in an unsafe situation or may have been influenced to leave your home. My job is to check on your wellbeing, ask a few questions, and determine whether any services are needed.”

I kept my hands on the mug, not gripping, just resting. I let myself breathe.

“I understand,” I said.

Ms. Kline nodded as if that alone mattered, an adult acknowledging another adult.

“Are you here voluntarily?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“Do you feel safe here?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said again.

“Is anyone preventing you from contacting your family or returning to your home?” she asked.

“No,” I replied. “I’m choosing not to contact them at this time.”

Ms. Kline’s pen moved across the page.

“Do you manage your own finances?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “With legal counsel. My attorney can provide documentation.”

Eloise leaned forward slightly. “Her attorney is Mr. Whitaker,” she said. “We have the capacity statement and trust filings if you need them.”

Ms. Kline’s gaze lifted briefly to Eloise. Not suspicious. Just noting.

“Thank you,” she said. “I may request copies.”

Then she turned back to me.

“I’m going to ask a few orientation questions,” she said, and I could tell by the way she framed it that she didn’t want to embarrass me. She wanted to document. That was the difference. Carla wanted a test so she could fail me. Ms. Kline wanted a record so no one could twist fog into fact.

“What is today’s date?” she asked.

I answered.

“What town are we in?” she asked.

I answered.

“What is your full name?” she asked.

I answered.

She asked me who the president was, who the governor was, simple civic anchors. Then she closed her folder slightly and looked me in the eye.

“Mrs. Blakeley,” she said, “do you believe you were being pressured to leave your home?”

My throat tightened, but my voice stayed steady.

“Yes,” I said. “I believe my autonomy was being restricted. My keys and mail were moved. Access to parts of my home changed without my consent. A guardianship petition was filed without my agreement.”

Ms. Kline’s pen paused. “You said a guardianship petition was filed?”

“Yes,” I said. “It was dismissed.”

She looked up, and for the first time her expression sharpened, not with anger, with focus.

“Do you have documentation of that dismissal?” she asked.

Whitaker had already prepared it because Whitaker always assumed someone would require proof. Eloise stood and retrieved the folder we kept by the guest room desk. She set it on the table gently, like it was fragile, but because it was powerful.

Ms. Kline flipped through the pages slowly.

Trust filing. Statement of capacity. Court dismissal. Notice to preserve property. Receipts. Timelines.

Her eyebrows rose just slightly.

“This is thorough,” she said.

“I had time,” I replied, then realized the sentence sounded too sharp, too close to the basement. I softened it without apologizing. “I had reason.”

Ms. Kline nodded, then asked a question Carla never asked me because Carla never wanted the answer.

“What do you want, Mrs. Blakeley?” Ms. Kline said.

It shouldn’t have made my eyes sting, but it did. Not because the question was sentimental. Because it was respectful.

“I want to live where I choose,” I said. “I want my choices to remain mine. I want to be treated like a person, not a project.”

Ms. Kline’s gaze didn’t flinch. She wrote for a moment, then closed the folder.

“Based on what I’m seeing,” she said, “I have no concerns about your safety here or your ability to make your own decisions. The report will be noted as unfounded.”

Eloise let out a breath she’d been holding.

Ms. Kline stood, tucked her folder under her arm, and looked at me again, softer.

“I’m sorry someone made you go through this,” she said.

I didn’t say it’s fine. I didn’t say thank you. I said what was true.

“I’m glad someone checked,” I replied. “It matters that it’s on record.”

Ms. Kline nodded like she understood why record mattered more than comfort.

At the door, she paused and added, “If anyone contacts you again through agencies or tries to pressure you, call my office directly. Don’t go through them. Don’t be alone in it.”

“I won’t,” I said.

After she left, the house felt quiet in a different way. Not tense. Cleared.

Eloise walked back to the kitchen and leaned against the counter.

“Well,” she said, “there goes that little plan.”

I sat back down and looked at my notebook. My pen was still on the page, hovering near the last line I’d written the night before.

They locked the door, but I still had the key.

And I used it.

I wrote one more sentence underneath.

And when they tried to call me confused, the record said otherwise.

The calls didn’t stop immediately. They changed shape. That’s what people like Carla do. When one door closes, they look for windows. She couldn’t pull me back with cake and soft voices anymore. She couldn’t corner me with a doctor at my kitchen table. She tried the court. She tried APS. When those failed, she tried the town.

Eloise’s phone began buzzing with unfamiliar numbers. Mine did too, my new one, the one I didn’t give out except to Whitaker and the bank and the shelter director. People are good at finding ways to reach you when they want a reaction.

One afternoon, as Eloise and I were unloading groceries, her neighbor called over from the driveway.

“Eloise,” the woman said, friendly and curious. “Everything okay? I heard you’ve got company.”

Eloise didn’t pause. She set a bag down on the porch and smiled in a way that didn’t invite gossip.

“My friend is staying with me,” she said. “Yes, everything’s fine.”

The neighbor leaned closer, voice lowering like a secret.

“Someone posted online,” she said. “About… you know. An older lady leaving her home. People are saying all kinds of things.”

Eloise’s smile stayed polite, but her eyes cooled.

“People say things,” she replied. “Truth doesn’t need a crowd.”

The neighbor looked slightly disappointed, as if Eloise had refused to give her a snack.

That night, Eloise showed me the post on her tablet. A neighborhood forum full of half-sentences and speculation, the modern version of porch whispers.

Concerned about an elderly woman. Family trying to help. Manipulated. Lawyer involved. Sad situation. Pray for them.

Carla didn’t sign her name, of course. Carla never signed her name when she wanted to throw mud. But I recognized her phrasing. The soft words that hid sharp intentions.

Eloise scrolled, jaw tight.

“They don’t even know you,” she said.

“That’s the point,” I replied. “They know the story she wants to sell.”

Eloise looked at me. “Do you want to respond?”

I thought about what it would feel like to type my own defense into a forum where people treated my life like entertainment. I imagined Carla reading it, smiling because she’d finally pulled me into a public tug-of-war where she could perform.

“No,” I said. “Whitaker responds. Paper responds. I don’t feed a rumor mill.”

Eloise nodded once, approval clear.

“Good,” she said. “Let them chew on silence. Silence can be a weapon when it’s chosen.”

Whitaker advised one more step, and I could tell by his tone he considered it both practical and symbolic.

“We file a notice with the post office,” he said. “We ensure your mail is forwarded properly and that no one else can redirect it. We also consider a protective order regarding harassment if needed.”

“A protective order?” I asked, not because I doubted him, because the phrase felt heavy, like an escalation.

“Not necessarily,” he said. “But we document. And we remain prepared. Your son’s wife has shown a pattern of using systems to create pressure. We don’t ignore pattern.”

Pattern.

That word became my compass. It made everything simple without making it easy.

Eloise and I drove to the post office on a bright, cold morning. The kind of small-town post office with flags out front and old bulletin boards inside advertising bake sales and lost pets. The clerk behind the counter wore reading glasses and moved slowly, not from age, from habit.

“How can I help you, ma’am?” she asked me.

The word ma’am felt different than Mom. It didn’t claim me. It didn’t reduce me. It acknowledged me.

“I need to confirm mail forwarding,” I said. “And I need to ensure no one else can make changes without my authorization.”

The clerk nodded like she’d heard similar things a hundred times, because she probably had. Families do this to each other more than anyone wants to admit.

She handed me forms. I filled them out in neat handwriting. Neat again, not because I was trying to impress anyone, because neat was evidence.

When it was done, the clerk stamped the papers and slid them back.

“All set,” she said. “Only you can make changes now.”

I walked out of the post office and breathed the cold air like a person stepping into a version of the world where locks worked the way they were supposed to.

After that, I let myself begin the part I’d been delaying, the part that frightened me more than courts and agencies.

Grief.

Not for Carla. Not even for my son exactly. Grief for the shape my life had been before people started folding it inward. Grief for the version of Michael who used to hold doors for me and bring me tomatoes from the garden. Grief for the kitchen that had smelled like bread and cinnamon before it smelled like lavender cleaner and staged emptiness.

The grief came in odd moments. When Eloise opened a drawer and offered me a new set of measuring spoons because she noticed my hands still reached for the old ones by reflex. When I saw a mother and adult son laughing in a diner booth as I walked past the window. When I woke at dawn and for a split second thought I was back in my bedroom, back in the house, back in the life where my biggest worry was whether the gutters needed cleaning.

Eloise didn’t try to fix it. She didn’t say time heals. She didn’t say at least you’re safe. She simply made space.

One evening, she poured two glasses of wine and sat across from me at her table.

“You keep looking like you’re bracing for something,” she said.

“I am,” I admitted.

“For what?” she asked.

I stared at the rim of the glass.

“For the moment I stop being angry,” I said. “Because then I’ll feel everything else.”

Eloise nodded slowly.

“Let it come,” she said. “Anger is useful. But it’s not a home.”

I thought about that later in bed, the lamp casting a small circle of light on the quilt. Robert’s letter lay folded in my bedside drawer. I took it out and reread the line that always caught in my throat.

Don’t let them shrink you.

The next week, the shelter director invited me to visit the building site where the new wing would eventually go. It wasn’t glamorous. A patch of land behind the existing building, a few stakes in the ground, a rough plan printed on large paper.

But I stood there with a hard hat perched awkwardly on my hair and felt something like peace move through me. Not because money fixed anything. Because purpose did.

The director, a woman named Marisol with kind eyes and a tired smile, walked beside me.

“We don’t want to make this a monument,” she said. “We want it to be functional. Warm. Safe.”

“Warm matters,” I said.

Marisol glanced at me. “You know,” she said softly, “a lot of women don’t realize what’s happening to them until it’s too late. They think it’s love. They think it’s help.”

“I thought that too,” I admitted.

Marisol’s gaze stayed gentle. “What changed?”

I didn’t give her the whole basement. I didn’t need to. I gave her the truth under it.

“They started making decisions around me like I wasn’t in the room,” I said. “That’s when I woke up.”

Marisol nodded like she’d heard the same sentence from a hundred mouths. That’s what made my stomach tighten. It wasn’t rare. It wasn’t special. It was a pattern.

On the drive home, Eloise glanced at me at a red light.

“You looked lighter,” she said.

“I felt useful,” I replied.

“Good,” she said. “Let usefulness replace guilt. You don’t owe guilt to anyone who tried to take your autonomy.”

The next change came in a plain envelope from Whitaker’s office, the kind with no drama on the outside. Inside was an update and a warning.

Carla had contacted the realtor.

Not to ask about the sale, because by then the sale was done and the documents were filed.

To complain.

To imply I hadn’t been in my right mind. To suggest the transaction should be questioned.

Whitaker’s note, typed cleanly, said: She is attempting to create doubt after the fact. We have sufficient documentation to rebut. Do not engage.

Eloise read it and snorted.

“She’s still trying to get her hands on what she can’t touch,” Eloise said.

“She doesn’t understand the kind of lock Robert built,” I replied.

Whitaker followed with another letter, formal and cold, sent directly to Carla’s attorney now, because at some point even people like Carla realize charm doesn’t work on paper.

It stated, again, that my capacity had been verified. That the sale was executed properly. That any attempt to interfere would be met with legal action. It reminded her that false claims could carry consequences.

Consequences. That word had become my quiet friend. It wasn’t revenge. It was boundary.

A few days after that, Michael called.

Not through the flip phone. Through my new number, which meant he’d either gotten it from someone or found it in a way that made my skin crawl slightly. When the screen lit up with his name, my stomach tightened, and for a second my hand hovered.

Eloise watched from across the room. She didn’t tell me what to do. She just waited, ready to hold whatever happened.

I let it ring out.

Then it rang again.

Then a text appeared.

Please. Just talk to me.

I stared at it for a long moment. A simple sentence that would have melted me once, when he was twelve and begged me to stay in the room after a nightmare.

But nightmares change when your child becomes the person signing the paperwork.

Eloise’s voice was gentle.

“You don’t owe him access,” she said. “You can choose if you want it.”

That word again.

Choose.

I took a slow breath, then typed one sentence.

If you want to communicate, speak through Whitaker.

I hit send. Nothing more. No explanation. No emotion. Just boundary in black letters.

My phone didn’t buzz again that night.

A week later, a letter arrived from Michael through Whitaker’s office. Whitaker forwarded it without comment, because that was his style. He didn’t interpret feelings. He interpreted risk.

Michael’s handwriting was neat, more careful than it used to be. The letter was longer than it needed to be, full of regret shaped like self-pity.

He said he was sorry things went “so far.” He said he was under pressure. He said Carla was “worried.” He said he didn’t know what else to do. He said he missed me.

He never wrote the sentence that mattered.

I let her lock you out.

I wanted the house.

I laid the letter on the table and stared at it until the words blurred.

Eloise sat down beside it and read it once. Then she pushed it away as if it smelled bad.

“He’s still trying to make you carry his shame,” she said.

I swallowed hard. “He’s trying to feel forgiven without facing what he did.”

Eloise nodded. “That’s easier than accountability.”

I filed the letter in the folder Whitaker labeled FAMILY CORRESPONDENCE because Whitaker treated emotion like evidence, and in a way, it was. If Michael ever tried again to rewrite the story, his own words would show how carefully he avoided the truth.

The following month, we went back to my old town for one reason only: to retrieve what had been taken.

Not furniture. Not dishes. Not things Carla could claim she was “organizing.”

Documents.

Whitaker had discovered through the deputy’s notes and my list that several personal records were missing. He filed a demand for return. Carla ignored it. Then Whitaker subpoenaed the records from institutions where possible, but some items were unique, originals, the kind of paper you can’t replace with a copy when someone is trying to twist your life.

We returned with Whitaker and a deputy again, not as a spectacle, as a structure. Carla wasn’t living there anymore, but she had left boxes in the garage labeled with her handwriting, as if she still believed the house was temporarily misassigned.

The new owners hadn’t moved in yet. The sale had closed, but they were renovating. The house was in that in-between state, empty of people but full of echoes. When I stepped inside, the air smelled like dust and paint primer, and I felt something pinch in my chest, sharp and quick.

Not longing. Not regret.

Just memory.

Whitaker guided us to the garage where the boxes sat. The deputy watched as Whitaker opened them one by one, careful not to disturb anything more than necessary. Inside were my things, mixed in with Carla’s, as if she’d been sorting my life like it was a thrift haul.

My winter scarves. My recipe box cards. A bundle of photos tied with string. The folder of documents I’d noticed missing. Robert’s service papers, slightly bent. Old tax returns. The mortgage payoff letter. The original copy of our marriage license.

My hands shook then, not from fear, from the shock of seeing my identity handled like clutter.

Whitaker glanced at me. “You’re alright,” he said quietly. Not a question. A reminder.

I nodded and kept going.

At the bottom of one box, beneath a stack of beige throw blankets Carla had bought for staging, I found my jewelry box.

It was open.

The little velvet slots were empty.

My throat tightened.

Whitaker saw my face change and leaned closer. “What is it?” he asked.

“My mother’s ring,” I said, voice low. “And Robert’s watch.”

Eloise’s eyes flashed. “She took them.”

Whitaker’s expression stayed calm, but his jaw tightened slightly.

“We document,” he said. “Now.”

The deputy took notes. Whitaker photographed the empty slots, the opened clasp, the box’s position in the larger container. He treated it like a crime scene because in a way it was. Not dramatic. Not violent. Just theft wearing perfume.

“We’ll send a demand letter,” Whitaker said. “If she refuses, we escalate.”

Eloise’s voice turned sharp. “She’ll deny it.”

Whitaker nodded. “Then we let her deny it in writing.”

That was Whitaker’s gift. He understood that the truth doesn’t always win quickly, but it wins cleanly when you make people commit their lies to paper.

Two days later, Carla responded through her attorney, of course. The letter was full of careful language. She claimed no knowledge. She claimed confusion. She claimed it must have been misplaced. She claimed she had only been trying to “help organize.”

Whitaker’s reply was shorter. It requested the items be returned within a specified timeframe and warned of legal consequences. It attached the deputy’s notes and the photographs.

Carla returned the ring and the watch a week later, dropped off anonymously at Whitaker’s office in a padded envelope. No note. No apology. Just objects returned when the spotlight moved close enough to burn.

When Whitaker handed them to me, I held the ring in my palm and felt its weight. My mother wore it every day of her marriage, her hands always smelling faintly of soap and flour. Robert slipped it onto my finger on our wedding day because my mother insisted, a tradition, she said, a blessing.

Carla had held it at some point, decided it was hers to keep, then decided it was safer to give back when paper got involved. That’s who she was. A woman who didn’t understand sentiment but understood risk.

Eloise watched me slide the ring back onto my finger.

“Feels right,” she said softly.

“It feels like myself,” I replied.

After that, the town quieted. Not because people stopped talking, but because my story stopped being available for their entertainment. There was no missing person report. No court drama. No scandalous reveal. Just a woman who left, filed papers, protected her assets, and started showing up at a shelter with a notebook and a steady listening face.

That bored them.

Boredom is a strange ally. It’s what happens when you refuse to perform your pain for people who didn’t earn the right to watch it.

As spring settled in, my routines became less like survival and more like life. Thursdays at the shelter. Tuesdays with Whitaker on the phone, brief updates, small legal maintenance. Sundays at Eloise’s kitchen table, where she insisted on making pancakes like we were teenagers again, laughing at nothing and then laughing harder at the fact that we were laughing.

One afternoon, Marisol asked if I’d speak to a small group of volunteers. Not a speech, she said. Just a conversation. A reminder that independence doesn’t expire.

I hesitated.

“I don’t want to be a symbol,” I told her.

Marisol’s expression softened. “You already are,” she said. “You don’t have to perform it. Just be real.”

So I sat in a small room with a circle of folding chairs and a pot of coffee that tasted like it had been sitting too long. The volunteers were mostly women, a few men. Some young, some gray-haired. Their faces held the same mix of compassion and fatigue, the look of people who wanted to help and had learned that help is complicated.

Marisol introduced me simply. “This is Lauren,” she said. “She’s part of why we’re building the new wing.”

No last name. No drama. Just Lauren.

A young woman with a ponytail asked the first question.

“How did you know?” she said. “How did you know it wasn’t help?”

The room went quiet.

I thought about Carla’s polite voice through the kitchen wall. I thought about the pamphlet for senior living slid across my table like a verdict. I thought about the key in Carla’s hand when she laughed too brightly and said the door was stuck.

“I knew,” I said slowly, “when they stopped asking me. Help asks. Control tells.”

A man across from me nodded, eyes down. A woman beside him wiped her cheek quickly and pretended she hadn’t.

Another volunteer asked, “Were you scared?”

“Yes,” I said. “But fear isn’t the end of the story. It’s a signal. It tells you where you’ve been trained to be quiet.”

Marisol watched me from the corner, her eyes shining slightly, as if she’d been waiting for someone to say that sentence out loud.

Afterward, as people filed out, one older woman stayed behind. She had silver hair and hands that shook slightly as she held her purse.

“I needed to hear you,” she said. “My daughter started paying my bills last year. She says it’s easier. I thought it was love.”

My throat tightened because I recognized that sentence, the way it sits in your mouth like a prayer.

“Do you have access?” I asked gently. “Can you see your accounts?”

She hesitated. “Not really,” she admitted. “She says I don’t need to worry.”

I reached for my notebook and wrote down Whitaker’s office number, then Marisol’s, then the shelter’s legal clinic times.

“Worry is a signal,” I told her softly. “Not a flaw. And you do need to see. Not because you don’t trust her, because your life belongs to you.”

The woman stared at the numbers on the page like they were a door.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

As she left, Eloise, who had come to pick me up, stood in the doorway with her arms crossed and a look that said she had been watching the room like a guard dog.

“You’re dangerous,” she said in the car.

I blinked. “What?”

Eloise smiled slightly. “To people like Carla,” she said. “You’re the kind of woman they can’t manage once you’re awake.”

That night, I lay in bed and listened to wind move through Eloise’s trees. The room smelled faintly of rosemary and old books. The lamp light reflected off the ceramic bluebird’s wing, a small glint like a heartbeat.

I thought about the basement again, not as a trap now, but as a threshold. The safe. Robert’s handwriting. The window latch still working because no one thought to check. The way the cold air hit my face like a wake-up call.

Then I thought about the courtroom, the judge’s calm voice, the word dismissed. I thought about Ms. Kline from APS saying unfounded. I thought about Carla returning the ring and watch in silence because paper had corners sharp enough to cut.

And I realized something that made me smile in the dark, small and private.

They had tried to control the story, but they had done the one thing that always backfires on people like them.

They underestimated how much I remembered.

Not just numbers and keys and codes. They underestimated the older, deeper memory. The memory of building. The memory of surviving. The memory of making a life with my hands and then refusing to have it folded away by someone who wanted the space.

The next morning, Eloise found me at the kitchen table with my notebook open.

“You’re writing again,” she said.

“Yes,” I replied.

“For the paper?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “For me. The paper was a warning. This is a map.”

Eloise poured my tea and set it down beside the notebook.

“Well,” she said, taking a sip of her coffee, “keep mapping. Because the road you’re on now? It’s yours.”