In 1831: A Countess and a Slave Swapped Babies and Brought Down an Entire Dynasty.

The Secret That Began with a Birth

On a humid August morning in 1831, in the heart of South Carolina’s rice and cotton empire, two children were born just a few hundred yards apart but belonged to completely opposite worlds where hierarchy, racial violence, and inherited power prevailed.

One child was born in the luxurious bedroom of the Bowmont estate, a 2,000-acre plantation famous throughout the lowcountry for its wealth, French Creole lineage, and strict insistence on pure blood. The other child was born in the cramped slave quarters behind the cane barn, a windowless room patched together from pine boards and scraps of tin.

The children, a frail white girl and a strong enslaved boy, were never meant to meet. Yet before the sun rose again, they would be bound into a story of deception so profound it would topple one of the oldest and most feared dynasties in the Carolina lowlands.

Historical records rarely note the moment a dynasty begins to decline. Yet Bowmont’s slow collapse began with the first cry of two children and the silent calculation of one woman.

That woman was Mrs. Genevie Bowmont, the 31-year-old wife of Colonel Thaddius Bowmont, a descendant of French Huguenots proud of their unblemished lineage, a phrase that appeared repeatedly in family letters and estate records.

According to oral histories preserved by descendants of the enslaved community, Genevie had only one obsession stronger than loyalty to the Bowmont name: producing a male heir strong enough to continue it.

But on that day, when the midwife placed a pale, underweight baby girl in her arms, something inside Genevie hardened like cooling iron. Outside the room, the colonel’s overseers fired celebratory shots into the air. Inside, Genevie looked at her daughter with an emptiness almost calculating.

When she heard that Eliza, her enslaved maid, had given birth to a healthy baby boy that same night in the quarters, a different idea formed, dangerous, unimaginable, yet intoxicating in its simplicity.

Genevie believed that a lie could save everything she valued.

That night, under pressure, Eliza was forced into a pact that historical records do not officially acknowledge, but many later testimonies indicate, the two children were switched.

The white child born into privilege was stripped of her name and assigned a life of bondage. The enslaved child born to a Black woman was named Elias Bowmont and became the heir.

This was not merely a crime. It was an assault on the social structure of the South.

It was also a secret that many, including Genevie, believed would never be revealed.

But lies born in the dark have a way of rotting.

And in the antebellum South, rot had a stench that could not be ignored.

A House Built on Cotton, Color, and Control

To understand how such a deception could survive for decades, one must understand the world Genevie ruled.

The Bowmont plantation was not simply a farm; it was a microcosm of Southern ideology, a closed ecosystem where power radiated in concentric circles from the main house. Diaries of neighboring planters often referred to the Bowmonts as “keepers of the old ways,” a euphemism for maintaining brutally strict racial categories and punishing any breach with near-religious fury.

For the Bowmonts, whiteness was not merely identity; it was capital, currency, armor, and weapon.

Genevie grew up in this culture. She breathed it like church air.

But what made Bowmont unique and particularly vulnerable was its uncompromising emphasis on bloodline. Few Southern families fetishized genealogical purity like the Bowmonts. Each generation recorded births, marriages, deaths, and alliances meticulously as if maintaining a royal line. A surviving relative wrote in a 1844 letter:

The Bowmont name rests upon the shoulders of the unborn son and God help the woman who fails to produce him.

Into this culture, Genevie, faced with a fragile daughter and the judgment of an entire lineage, made her fateful decision.

And she executed the deception with surgical precision.

Eliza, powerless to resist, swore secrecy. Those who assisted either remained silent or disappeared from tax records later. The colonel, often away on political business, never knew. When the plantation midwife died of fever weeks later, only two women knew the truth, and only one held power.

By the time the white child, now renamed Nell, was old enough to walk, she was indistinguishable from other enslaved children except for her complexion, something easily explained by a distant ancestor, a common trope in plantation society. Because the plantation owner himself avoided the quarters, he never questioned this oddity.

Meanwhile, only Genevie knew that the enslaved boy, Elias, was being prepared, educated, and celebrated as the future patriarch.

The lie had fused into reality.

For now.

But deception of this magnitude always produces cracks, and Nell would be the first.

The Slave Girl Who Did Not Belong

Accounts from former enslaved residents describe Nell as different. They spoke of a child with skin too fair, eyes full of questions, and quiet resistance unnatural for her status.

Even as a child, Nell felt the disconnect. Something in her bones whispered that the world she endured was not the one she was meant to inhabit. In later interviews conducted in the 1890s by WPA historians, descendants recalled a family story:

She looked at the big house as if remembering a dream.

Despite cruel treatment, Nell displayed a sharp mind that unsettled Genevie. In the South, literacy among enslaved people was illegal and punishable, but curiosity itself was dangerous. When Nell was caught staring at a discarded newspaper near the veranda, Genevie reacted not with discipline but with something colder: fear.

Fear that the child she condemned might claw her way back to the truth.

This fear metastasized into cruelty.

She had Nell moved from fieldwork to the attic archives, a dusty chamber suffocating with heat and silence. It was a punishment designed to break the spirit, not the body. Genevie intended to bury Nell in monotony, sorting old ledgers, estate papers, and family records she was never meant to understand.

What Genevie underestimated was simple: Nell was smarter than she realized. The attic was not a grave; it was a library.

The Girl Who Learned to Read the Lies

Long-form reporting often seeks the moment a victim becomes an investigator. Nell’s moment happened quietly, unnoticed by anyone except an older house servant named Clara who brought her meals and unwittingly became a conduit of information.

The attic was meant to isolate her. Instead, it exposed her to materials Genevie should never have allowed near her: birth ledgers, transfer deeds, private letters, records of transactions both personal and political.

Though she could not read fluently, she taught herself through repetition, pattern, and context. Words became shapes she learned to decode, slowly at first, then with startling speed.

This was an unintentional education and an irreversible one.

Nell began noticing inconsistencies: a missing witness signature on the Bowmont birth record, a second ledger listing two births on the same date, financial entries indicating unexplained payments around the time of her birth, correspondence referencing a delicate matter never explained.

Alone in the attic, she felt a rising dread. She sensed that the cracks she spotted were not clerical errors but fractures in the foundation of a lie.

Though she did not yet understand who she was, she sensed one truth with perfect clarity: Genevie feared her.

That fear was a clue, not just about herself but about a secret so dangerous it threatened the entire house.

The Boy Who Did Not Belong Either

While Nell examined papers, Elias lived an entirely different life.

To the outside world, he was a Bowmont heir, well-dressed, well-educated, prepared to inherit power he did not know had been stolen from someone else.

Observers noted something unusual in him. Diaries kept by visitors to the plantation described Elias as kind to the coloreds, melancholy, and strangely detached from his station.

He often wandered the fields visiting enslaved workers, not with authority but with curiosity and even affection. He lingered near the quarters. He spoke to Eliza, unaware she was his biological mother.

The bond was instinctive and inexplicable. Nurture, modern psychologists would say. Blood, older voices might whisper.

But Elias himself felt the disconnect deeply. He once confided to the plantation’s pastor that he felt unrooted, as if he fit everywhere and nowhere.

A telling line in light of later revelations.

The Woman Who Kept the Evidence

While Nell and Elias were unknowingly approaching the truth, Eliza, the enslaved woman who had been forced to swap her child, created a different kind of record.

She kept a private diary, written in shaky but legible handwriting, recording every detail she could remember from 1831: the swap itself, Genevie’s threats, the infants’ distinctive features, statements made under duress, and the midwife’s final words before her death.

She also preserved physical evidence: a baby’s embroidered garment, a lock of blonde hair, and a small ring Genevie had once dropped near the cradle.

These were relics of a truth that could one day either set the two children free or destroy them.

Eliza hid the diary under the floorboards of the sugar shed.

She told only one trusted confidante, Sarah, another enslaved woman whom she considered like a sister.

She gave Sarah one instruction:

“If I die, guard this. If she rises, give it to her.”

Eliza could not yet know that she was protecting the very documents that would one day shatter the Bowmont empire.

The Long Game Begins

By 1858, Nell had become more than a quiet slave girl.

She had become a strategist.

Her supposed “mistakes” in organizing the attic were no accident.

She began planting subtle seeds of disorder: misplacing noncritical documents, leaving certain letters open, rearranging pieces of correspondence, and placing odd papers for Elias to stumble upon.

These were not acts of rebellion; they were reconnaissance.

She watched Genevie unravel slowly under declining health, insomnia, and growing paranoia. She observed Elias becoming more distant and uncertain of himself. She noticed the Bowmont social circle tightening, sensing instability without understanding its cause.

Nell did not yet know her exact place in the world.

But she knew something more important:

Genevie had built the entire dynasty on a lie, and the lie was cracking.

All Nell needed was the right moment.

And fate would soon provide it.

The Death of the Patriarch

In late autumn of 1858, Colonel Thaddius Bowmont suddenly died of a stroke after returning from Columbia. His death triggered the most important ritual of plantation aristocracy, the reading of the will.

Local elites, including planters, lawyers, and distant relatives, gathered in the Bowmont parlor under chandeliers imported from Paris, expecting a simple transfer of power to Elias.

Mrs. Genevie Bowmont, dressed in black silk, sat at the front, her face showing rehearsed sorrow. She believed the transition would be seamless.

But one person entered the room who could change everything:

Reverend Silas Croft, the family’s attorney.

He brought with him a sealed envelope and a leather-bound diary.

Both had been given to him years earlier and were to be opened only upon Thaddius Bowmont’s death.

When Croft paused during the reading, the room shifted.

When he announced the existence of a supplementary packet of critical relevance, Genevie turned pale.

And when he opened the packet and revealed Eliza’s diary, the parlor fell silent.

At last, this was the avalanche Nell had been waiting for.

The Revelation That Stopped a Dynasty Mid-Sentence

Reverend Silas Croft did not raise his voice. He did not need to.

The weight of the documents he held the diary, the baby garment, the lock of hair spoke louder than any accusation.

He read slowly and deliberately.

Journal entries from Eliza, dated 1831, describing Genevie’s coercion.

Descriptions of the infants, one pale, one strong and dark-haired.

The midwife’s recorded words, shakily transcribed.

Physical evidence sealed in wax, undeniable.

Within minutes, the Bowmont parlor a room designed for elegance and social power—became a courtroom, a confessional, and an execution chamber all at once.

Genevie screamed first.

Not in grief.

Not in denial.

In recognition.

Recognition that the one truth she had built her life upon—the truth she thought buried—was standing before society, exposed like a diseased root.

Witnesses later wrote that her reaction was animalistic, feral, the shriek of a cornered creature. Some described her collapse as hysteria. Others saw it as revelation. A few recognized it for what it was:

The sound of a dynasty dying.

Elias staggered back, his face drained of color.

Nell stood completely still, hands clasped, her gaze locked on the woman who had condemned her to a life in chains.

And Reverend Croft, calm throughout, closed the diary and delivered the verdict that would echo across the South:

“Elias Bowmont, by birth, is enslaved.

Eleanor Bowmont, enslaved for twenty-seven years, is the colonel’s true and only heir.”

No slave law, inheritance statute, or social custom had a contingency for this.

This was not a crack in the system.

This was a direct assault on the system itself.

And the system had no defense.

The Aftermath: Power Suddenly Without a Master

The revelation spread across the coastal lowlands like wildfire.

Within forty-eight hours, gossip reached Charleston, Savannah, Beaufort, and the rice islands. Bowmont was not merely another plantation; it was a symbol, a pillar of Southern lineage.

Exposing it as a fraud exposed the fragility of the very myth the South sold itself.

An abolitionist newspaper in Boston wrote, “This scandal upended the notion of inherited whiteness and made a mockery of the aristocratic South’s obsession with blood.”

Genevie Bowmont, once a woman of icy composure, disintegrated in public view. She denied everything, then confessed everything, then denied it again. She accused Eliza of witchcraft, Croft of conspiracy, and Nell herself of seduction, deception, and demonic influence.

Witnesses described her as a ghost in silk, wandering the halls, muttering to portraits of her ancestors. At times she shouted:

“She will not take my name!

She will not take my son!”

But the truth was indifferent to her unraveling.

And the law, overwhelmed by the unthinkable nature of the crime, hesitated but ultimately acted.

The Legal Storm and the Shattering of a Plantation

The probate hearing that followed became one of the most contentious legal spectacles in South Carolina’s pre-Civil War history. Unlike most enslaved people, Nell stood before the court not as property but as a plaintiff, with documentation proving her birthright.

White newspapers refused to print her name. Abolitionist papers printed it in bold.

In court, three revelations defined the case.

First, the DNA of the nineteenth century: the baby garment and hair. Though antebellum courts had no concept of genetics, physical evidence paired with precise diary descriptions left little room for doubt.

Second, the midwife’s testimony recorded before her death. Reverend Croft had preserved a dying statement from the midwife who attended both births. Her account, trembling with fever, described Genevie’s derangement and the unnatural exchange demanded at gunpoint.

Third, Elias’s resemblance to Eliza. Even hostile observers could not ignore the likeness.

One planter wrote privately:

The boy bears her nose, her brow, her manner of speech. The countess’s child does not resemble her in the slightest.

In the end, the court ruled in a decision that historians still debate.

Nell was the legal heir. Elias, by law, should have been enslaved but would not be claimed as such.

It was unprecedented. Unthinkable. Destabilizing.

The Bowmont estate was seized and temporarily held under trusteeship. For the first time in twenty-seven years, Nell walked out of a courtroom with papers granting her freedom and the legal right to what once chained her.

What Freedom Looked Like at the Edge of a Dying World

Nell’s first act as heir was deliberate, seismic, and profoundly symbolic.

She freed every enslaved person on the Bowmont plantation.

Not gradually. Not selectively. Not with conditions.

Immediately.

Witnesses recall that when she read the proclamation, written in her careful, self-taught script, many stood in stunned silence. Some cried openly. Eliza collapsed into her arms.

By noon, the plantation that once embodied the power of southern aristocracy had become a sanctuary.

This singular act enraged neighboring landowners, horrified politicians, and electrified abolitionist circles across the country.

Nell did not stop there.

She declared Bowmont land open for free settlement, equitable farming contracts, schooling, and community governance.

She refused to live in the manor house, calling it a monument to suffering. Instead, she moved into a modest cabin and began building a different kind of world, one in which literacy, ownership, and dignity were accessible to all who had been denied them.

Elias: The Heir Without a Name

For Elias, the revelation was an existential blow.

He lost his identity, his social standing, his inheritance, and the lie that shielded him from the cruelty of the world he unknowingly benefited from.

But he gained clarity and freedom from a role that always felt ill-fit.

Historical letters indicate he refused any special treatment, declining even Nell’s invitation to stay on the land. Instead, he traveled north, joining abolitionist circles and later helping establish schools for freed children.

One surviving letter from him reads:

I have lived a life stolen from another. May the years I have left restore what was taken.

In the decades that followed, Elias became a quiet, steady force in Reconstruction-era education, though many in the South refused to acknowledge him. But history does.

What Happened to Genevie

Genevie Bowmont did not face trial.

Not because she was innocent but because antebellum law simply had no mechanism to punish a white woman for a crime involving race, birth, and inheritance fraud on this scale.

Her punishment instead came through social exile.

Abandoned by her peers, stripped of wealth, and avoided by family, she spent her final years in a small rented house in Columbia, attended only by a distant cousin and a nurse.

Her journals, fragmented, paranoid, and occasionally lucid, contain passages like:

She watches me. She wears my name. My blood walks in the fields.

She died in 1864, in the third year of the Civil War, a war whose ideological roots were tangled with the same obsession over blood and supremacy that drove her crime in 1831. Her grave bears no marker.

The Birth of a New Community

After the scandal, Bowmont Plantation did not collapse. It transformed.

Under Nell’s quiet, steadfast leadership, it became a unique community, part school, part cooperative farm, part refuge for those fleeing harsher plantations.

Freed men and women built homes on land once marked for their bondage. Children learned to read in the old carriage house. A small printing press operated from the smokehouse. Rice fields were redistributed into smallholdings.

By the late 1860s, the land was known colloquially as Eleanor’s Rest.

A Northern journalist visiting in 1869 wrote:

If the Confederacy was a dream of blood purity and dominion, Bowmont is now its opposite, proof that the South might be rebuilt by those it once sought to break.

The Historical Significance of the Bowmont Scandal

Modern historians continue to debate the impact of the Bowmont scandal, but most agree on three points.

First, it undermined one of the South’s strongest myths, racial purity. The fact that a Black child lived as a white heir for nearly three decades terrified Southern elites. It demonstrated how fabricated, fragile, and easily manipulated the category of whiteness truly was.

Second, it exposed the moral rot at the core of the plantation system. Not through sensational violence but through a calculated act of maternal manipulation, revealing how deeply the institution corroded the souls of even its most respected families.

Third, it became a foundational narrative for postwar Black education movements. Nell and Elias, siblings by circumstance rather than blood, both contributed to early freedmen’s schools. Their intertwined stories became part of Reconstruction folklore.

One historian wrote:

The lie that destroyed a dynasty gave birth to a generation’s hope.

What Remains Today

The Bowmont manor no longer stands; it burned in 1888 under unclear circumstances. But the land, now dotted with renovated homes and historical markers, remains inhabited by descendants of the people Nell freed.

Only the stone steps of the old house survive, covered in moss, half eaten by vines. Visitors say the site feels strangely peaceful.

The attic where Nell discovered fragments of her identity is gone, but replicas of the documents she found are on display at a regional history museum, including the two birth entries, the mismatched land deed, Eliza’s diary with the original stored under controlled conditions, and the garment that once belonged to a baby condemned to bondage.

Nell herself never married. She died in 1897, surrounded by former students and neighbors. Her grave simply reads:

Elias died in Massachusetts in 1904, a respected educator. Their intertwined lives remain one of the most extraordinary, least known, and morally complex stories in the pre-Civil War South.

The Truth That Outlived the Lie

What makes the Bowmont scandal so haunting, even nearly two centuries later, is not just its audacity but its symbolism.

It forces us to confront a truth the South spent generations denying.

Race is a fiction. Power is a construct. And lies built to protect one will always destroy the other.

In 1831, one woman switched two babies to preserve a dynasty.

In 1858, those babies, grown into a woman and a man who never asked for the deception, brought that dynasty to its knees.

Their story is a reminder that even in eras built on cruelty and silence, truth has a strange persistence. It waits, like a seed buried under centuries of soil, for one crack in the foundation.

And when that crack comes, the truth grows with unstoppable force.

The Bowmont dynasty did not fall because of war, or economics, or politics.

It fell because a girl forced into bondage learned to read and chose to follow the truth wherever it led.

Sometimes revolutions begin not with gunfire or speeches but with a page turned in an attic by someone the world thought would never learn to read it.

News

When My Mother Accused My Son of Theft and Attacked Us at My Sister’s Wedding, Our Family’s Carefully Maintained Illusions Collapsed and Forced Us to Confront the Painful but Necessary Truth

I used to believe my family had its flaws but would never turn on me not truly, not violently. That…

They thought I was nobody. Four recruits surrounded me, saying I didn’t belong, that I was “taking a man’s place.” They never imagined they were provoking an undercover Navy SEAL. The moment they touched my arm, I reacted, and just fifteen seconds later they were lying on the floor, and I said…

“You’re taking a man’s spot.” That was the sentence that stopped me mid-stride on the training deck of Naval Station…

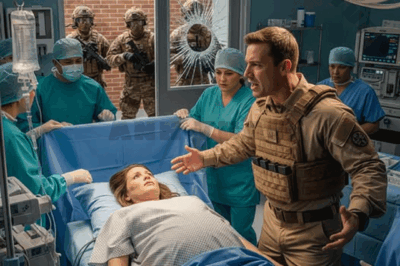

My mother-in-law and a doctor insisted on aborting my “defective” baby, forcing me onto an operating table after assuming my husband was dead. As the doctor raised his scalpel, the door flew open. My husband stood there in full combat gear and roared, “Who dares to touch my child?”

I never imagined fear could have a taste, but that night it tasted like metal sharp, cold, and lingering on…

They laughed at my cheap suit, poured red wine all over me, called me worthless, without knowing that I was carrying the evidence that could destroy the wealth, reputation, and lies they lived on.

I never imagined that a single glass of wine could expose the true nature of people who had once been…

A call from the emergency room shattered my night: my daughter had been beaten. Through tears and bruises, she whispered, “Dad… it was the billionaire’s son.” Not long after, he texted me himself: “She refused to spend the night with me. My dad owns this city. You can’t touch me.” And he knew I couldn’t. So I reached out to her uncle in Sicily, a retired gentleman with a past no one dares to mention. “Family business,” I told him. His gravelly voice replied, “I’m on my way.”

The call came at 2:14 a.m., slicing through the kind of silence that only exists in the dead of night….

My daughter-in-law invited the whole family to celebrate but did not invite me. A few hours later, she texted: ‘Mom, remember to heat up the leftover portion in the fridge. Don’t let it go to waste.’ I only replied: ‘OK.’ Then I packed my luggage and walked away. That night, when they returned and opened the door, the truth was already waiting on the table.

My daughter-in-law got a promotion. She took the whole family out to a restaurant to celebrate. But she didn’t invite…

End of content

No more pages to load