In the war’s final weeks, the rail yards were the kind of places maps lied about.

On paper, tracks connected towns, schedules held, cargo moved. In reality, sidings filled with abandoned cars, engines detached without explanation, and paperwork blew through broken stations like dead leaves. Units advanced faster than clerks could record. Orders changed faster than men could obey. The war didn’t end in one clean motion. It frayed, and in the fraying, people disappeared.

That was how a sealed freight car could sit on a side track for days without anyone claiming it, without anyone opening it, without anyone knowing how many lives were locked inside.

The American patrol wasn’t looking for prisoners. They were sweeping for hazards, for snipers, for anything left behind that might kill a man after the fighting had already moved on. The morning was cold and colorless, the sort of late winter day that made breath visible and sound carry farther than it should.

The patrol moved between cars with weapons low but ready, boots crunching on gravel. A crow called somewhere beyond the yard, harsh and impatient. The men spoke in short bursts, mostly hand signals, mostly the quiet habits of people who had learned that noise could invite trouble.

Then the youngest one stopped.

He didn’t raise his rifle. He just tilted his head as if listening for something he couldn’t place.

“What is it?” the sergeant asked.

The young soldier hesitated, embarrassed by his own uncertainty.

“I thought I heard… something,” he said.

The sergeant’s eyes narrowed. He listened. At first there was nothing but wind sliding through steel and the faint hum of distant engines. Then, barely there, a sound that wasn’t mechanical. Not metal settling. Not a rat.

A soft, irregular scrape.

The sergeant moved closer to the nearest sealed car, a rusted freight box with numbers stenciled on the side. The doors were shut tight. Someone had slid the locking bar into place and sealed it with a crude twist of wire.

He leaned in, bringing his ear near the seam.

Another scrape came, faint as a fingernail.

The sergeant’s jaw clenched. He stepped back and signaled.

“Crowbar,” he said.

A corporal pulled one from the truck. The men gathered at the door, weapons up for a moment, because they had learned to expect anything behind a closed space. The sergeant looked at the lock again, the wire, the bar.

“On three,” he said.

They pried, metal groaning with reluctance. Rust flaked into their gloves. The bar shifted a fraction, then another. The door resisted like it didn’t want to admit what it held.

The gap widened, and the first thin slice of air escaped from inside, warm and stale, carrying a sourness that made the young soldier flinch before he could stop himself. The smell wasn’t battlefield smoke or burning oil. It was human breath trapped too long in a box, mixed with fear and sickness and the raw chemistry of bodies left without care.

“Easy,” the sergeant said, though he wasn’t sure who he was calming.

They pulled again. The door slid with a harsh scrape, and gray light poured into the car.

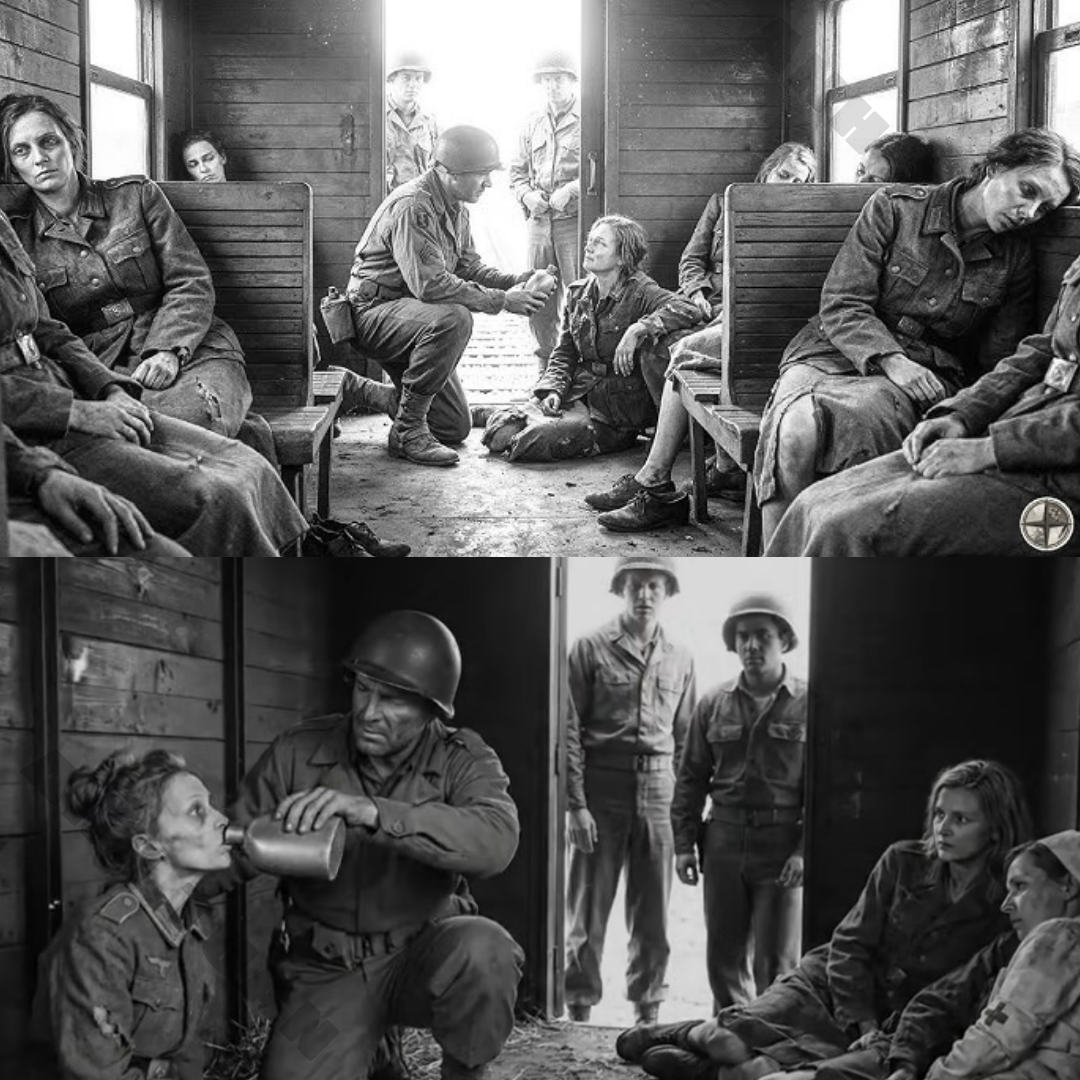

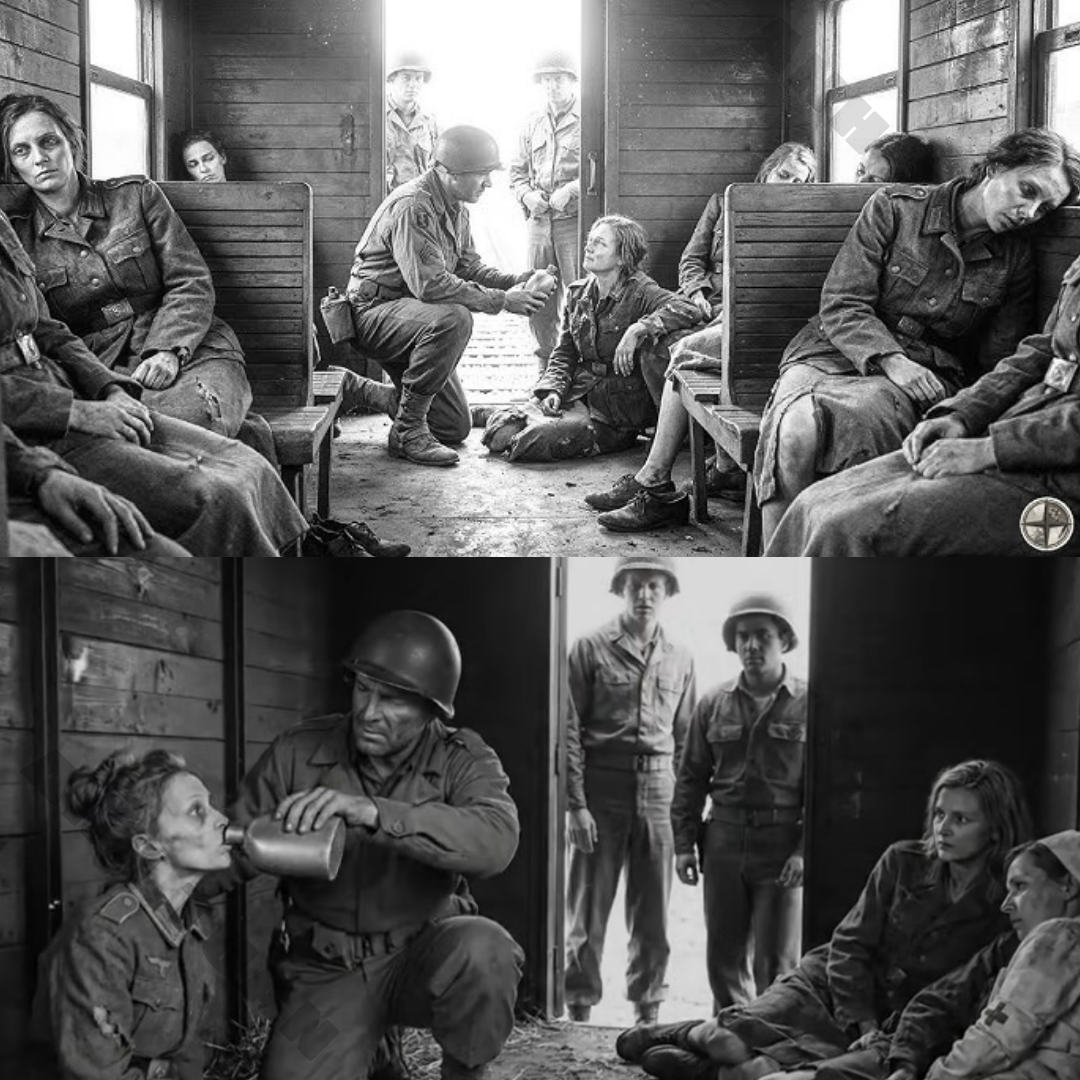

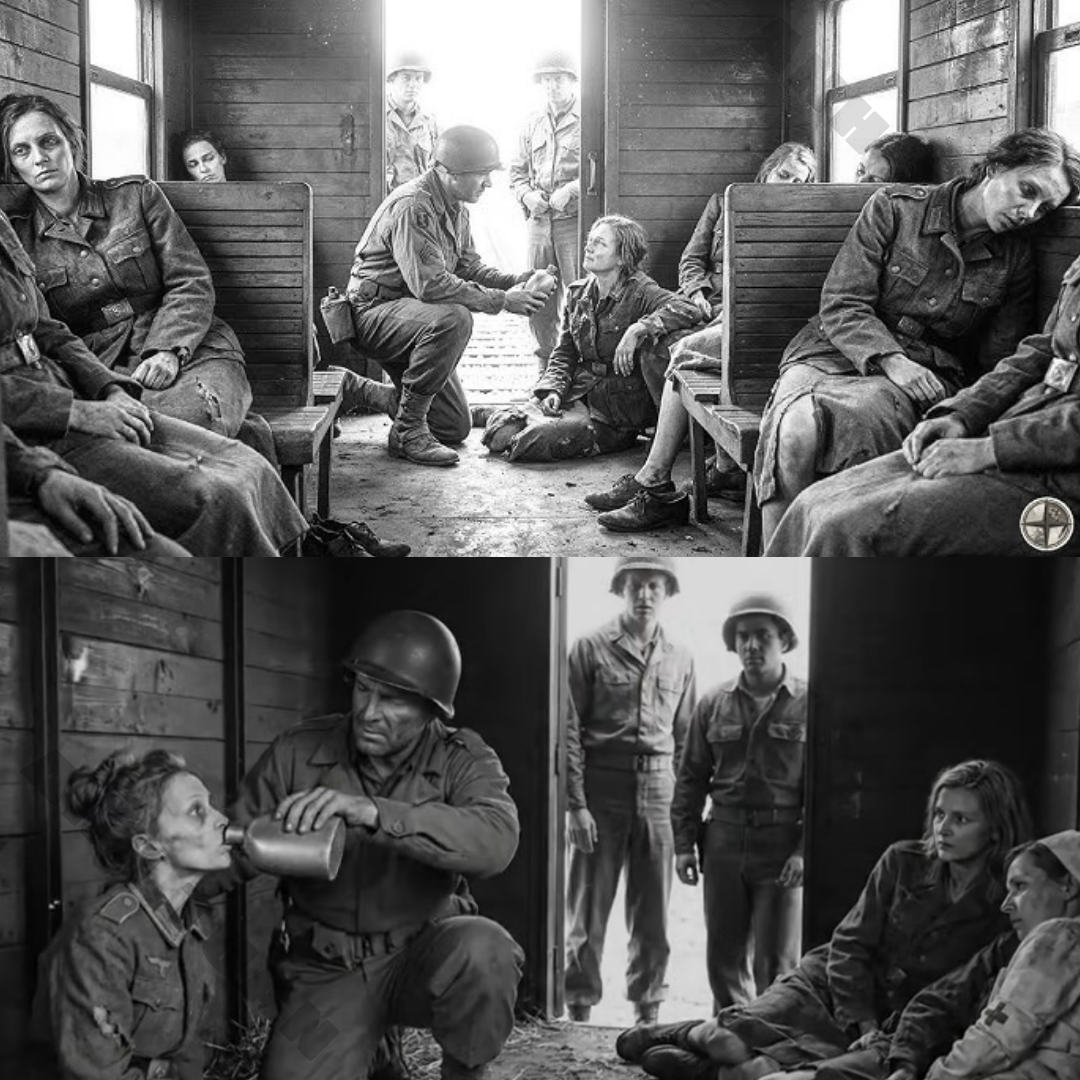

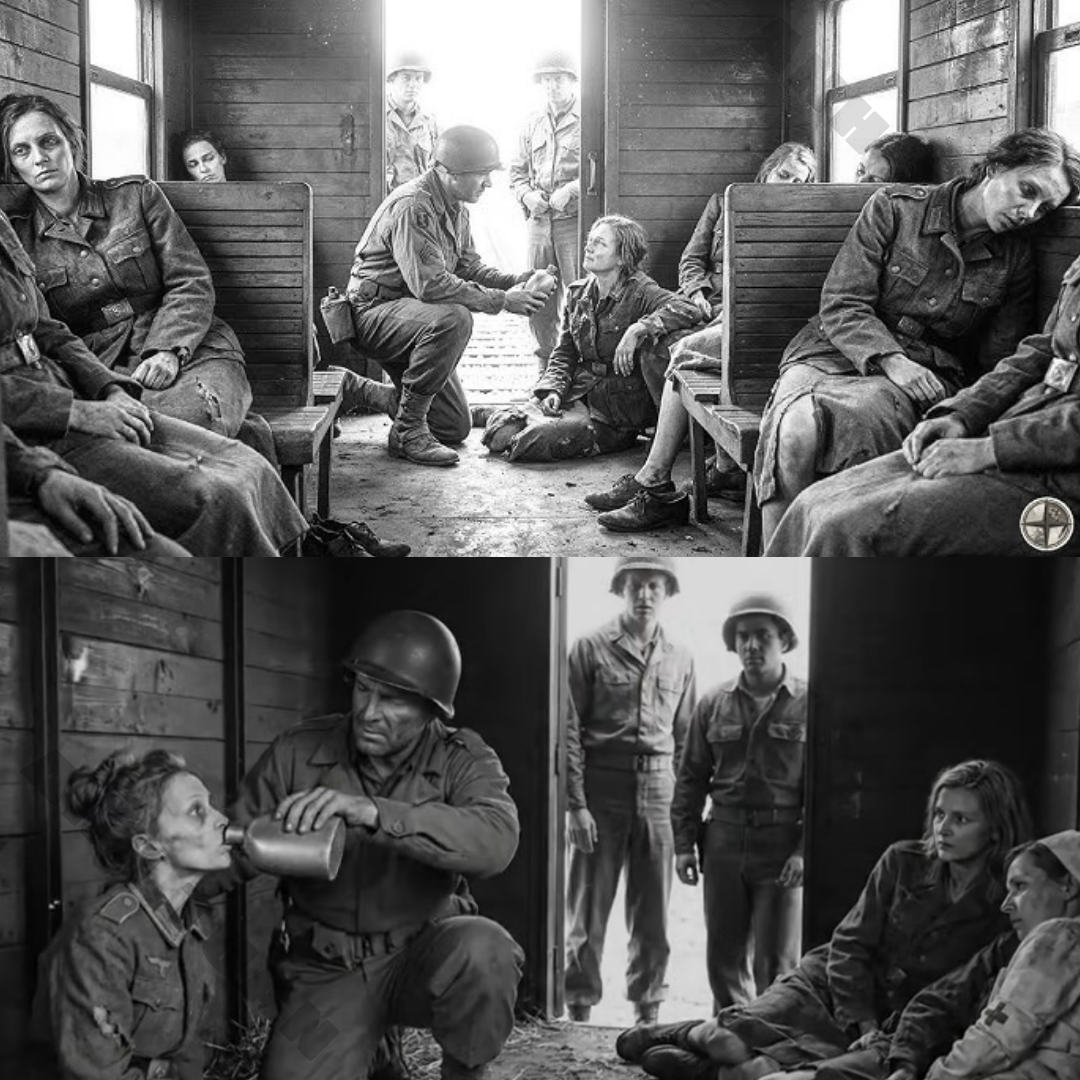

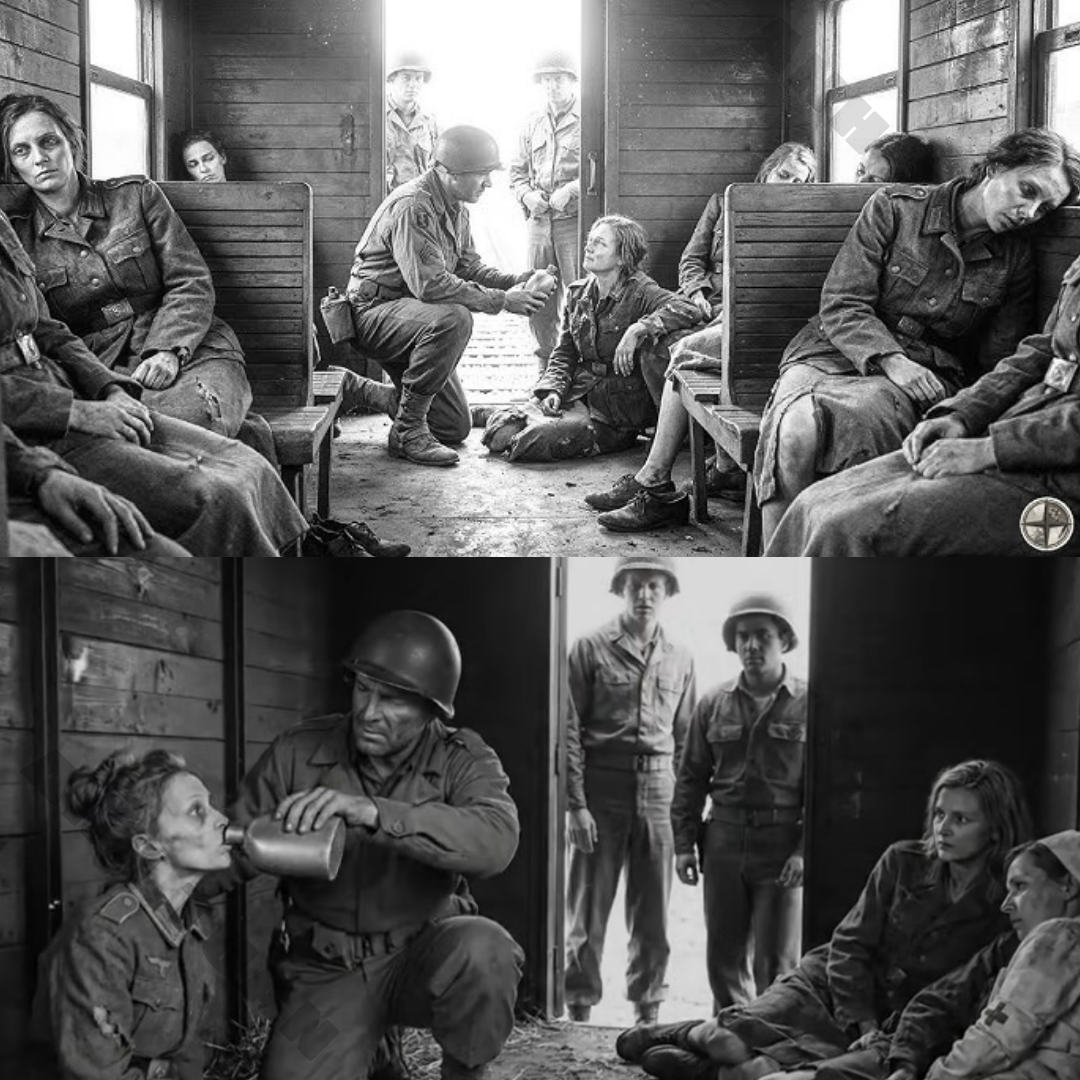

At first, the Americans saw shapes.

Then their eyes adjusted.

There were women inside, pressed into corners, piled together in a way that made the human body look like cargo. Some faces were turned toward the sudden light, eyes wide and glassy. Some faces didn’t move at all. The stillness wasn’t peaceful. It was the stillness of people who had spent days conserving every ounce of energy because movement had become expensive.

No one spoke.

That silence hit the men harder than any scream could have.

If the women had shouted, it would have fit a pattern. If they had surged forward, it would have been a story the soldiers already knew how to tell themselves. Instead, there was only that quiet, and it made the whole scene feel wrong in a way war rarely managed anymore.

The young soldier took a step forward and stopped, suddenly aware that his hands were shaking.

A woman near the front blinked slowly, as if the light hurt. Her hair was flattened against her skull. Her lips were split, dark with dried blood at the corners. Her eyes found the open door and held it with a stunned focus, not panic, not anger, but something like disbelief.

She tried to speak.

Nothing came.

The sergeant climbed up onto the edge of the car carefully. His voice came out softer than the war had trained him to be.

“Hey,” he said. “Hey. We’re here.”

The women didn’t react the way people expected. They didn’t cry out. They didn’t reach for freedom. A few shifted, slow and stiff, as if their bodies didn’t trust the invitation. Someone in the back made a sound that might have been a cough or a sob.

A medic pushed forward, canvas bag slung across his chest.

“Don’t flood them,” he snapped. “Nobody gives them a full canteen. Slow. Drop by drop. You understand me?”

The men nodded quickly. They weren’t offended by the tone. They were grateful for someone who knew what to do.

The medic climbed into the car and crouched beside the nearest woman, checking for breath, for pulse, for any sign that the line hadn’t been crossed. He pulled out a canteen and didn’t hand it over. He tipped it himself, letting one drop touch her lips.

“Just a little,” he said. “That’s it.”

The woman’s mouth opened with effort. The drop hit her tongue. She swallowed, her throat working like a machine restarting after being left in the cold.

Tears welled in her eyes, quiet and sudden. She didn’t wipe them away. She didn’t seem to notice them. Her body released something without asking her permission.

The young soldier watched from the ground, frozen.

“What do we do?” he asked, his voice cracking.

The sergeant didn’t look away from the car.

“We get them out,” he said. “Slow. One at a time.”

They carried the first woman out, her body light in their arms in a way that felt wrong. She didn’t resist. She didn’t cling. She let gravity take her because she didn’t have anything left to hold herself upright.

They laid her on a blanket on the gravel. Another soldier slipped his coat off and draped it over her without being asked. The wind cut through the yard, cold and careless.

They carried out the next woman, then the next.

Some gasped when fresh air hit their lungs, drawing breath in sharp, involuntary pulls as if air itself had become a shock. Others went limp, unconscious the moment their bodies realized they didn’t have to fight for oxygen anymore.

A few could walk with support, knees buckling, feet dragging like they had forgotten how to be bodies with weight. Their eyes moved over the rail yard with a blankness that wasn’t calm. It was distance. It was a mind stepping back from reality because reality had been too much.

The medic emerged from the car, face pale under grime.

“There’s more,” he said quietly.

The sergeant nodded once. He understood without being told.

Some of the women didn’t move at all. The men climbed back in and checked anyway, fingers pressed gently to necks, eyes scanning for the smallest rise of a chest.

When there was no pulse, the sergeant closed his eyes for a moment, not in prayer exactly, but in that pause people take when their minds refuse to accept what their hands have confirmed.

They carried the dead out too, because leaving them in the box felt like repeating the cruelty. They wrapped them in blankets and laid them down with faces covered, the yard suddenly lined with still forms that made even experienced soldiers swallow hard.

The lieutenant arrived with a truck and an expression sharpened by urgency. He jumped down, boots sinking into mud, eyes widening as he took in the line of women on blankets.

“What happened?” he demanded.

“Freight car,” the medic said. “Sealed. We think twelve days, give or take.”

“Twelve days?” the lieutenant echoed, as if language couldn’t hold that number.

The sergeant’s voice stayed flat because if he let emotion in, it would spill.

“We found it by accident,” he said. “No guards. No paperwork. Nothing.”

A nurse climbed down from the second vehicle, sleeves rolled, hair pinned back, her face composed in the way medical professionals learned to be. Her eyes moved over the women quickly, assessing, measuring.

“Warmth first,” she said. “Then fluids. Slow. No sudden feeding. No hero meals.”

Her voice softened when she crouched beside a woman whose eyes were open but unfocused.

“You’re safe,” she said, shaping the words slowly, like kindness was a tool. “You’re safe now.”

The woman’s gaze drifted toward her voice. A tear slid down the side of her face and disappeared into the blanket.

The nurse didn’t comment. She simply took the woman’s hand and held it, steady and present.

Ambulances arrived, and the yard filled with movement. Stretchers. Blankets. Med bags. Orders shouted and obeyed. The survivors were loaded carefully, one by one, bodies handled like fragile objects the war had almost broken.

The young soldier helped carry a stretcher. The woman on it was small under the blanket, cheeks hollow, eyelashes too long against skin that looked stretched. As they lifted her, her hand moved weakly, fingers grasping at air.

He reached without thinking and let her grip his sleeve.

The grip wasn’t strong, but it was desperate. The fabric became a lifeline because the human mind will cling to anything when it doesn’t trust the world yet.

He didn’t pull away.

A nurse saw the gesture and said nothing. She climbed into the ambulance, adjusting blankets, checking breaths, working quietly while the vehicle rocked.

As the convoy rolled out, the lieutenant stayed behind with a notepad and a pencil, the posture of a man trying to force chaos into sentences.

“Give me everything,” he said.

The medic described the sound, the sealed lock, the condition of the women. The sergeant described the lack of records, the way the yard looked abandoned, the way the doors had been wired shut.

“Who sealed it?” the lieutenant asked.

The sergeant shook his head.

“That’s the problem,” he said. “Nobody’s name is on it.”

The lieutenant frowned. “There should be a manifest.”

“Maybe there was,” the sergeant replied. “Maybe it burned. Maybe it got tossed when someone decided paper was heavier than guilt.”

They searched the broken station anyway. They found damp papers stuck together, ink smeared into blue ghosts. They found a calendar crossed off through March and then blank, as if time had stopped being worth recording. They found a tipped filing cabinet, drawers spilled, the contents mostly useless.

The lieutenant held up a torn sheet with names and numbers, half blurred.

“Could be something,” he said, not sounding confident.

The sergeant scanned it and handed it back.

“Not enough,” he said.

Later, they found an older rail worker still hiding nearby, hands raised automatically when he saw American uniforms. He spoke enough English to answer in fragments. His fear sat on him like a coat he couldn’t take off.

“That car,” he said, eyes flicking toward the track. “It was not supposed to stay.”

“Who put it here?” the lieutenant demanded.

The rail worker swallowed.

“Orders,” he said. “Many orders. One day, one order. Next day, another. People running. Bombs. Trains stopping everywhere.”

“Who sealed it?” the sergeant asked.

“A guard,” the rail worker whispered. “Not my man. Guard from, I don’t know. He sealed it and said, ‘Do not open. Prisoners.’”

“And then?” the lieutenant pressed.

The rail worker’s hands trembled. “Engine left,” he said. “Line ahead damaged. People fled. Yard full. No fuel. No orders.”

The sergeant watched him, his face unreadable.

“And you didn’t open it,” he said.

The rail worker’s eyes flashed with terror. “We could not,” he insisted. “If we open, we are shot. If we open and they escape, we are shot. If we open and there are dead, we are shot. No good.”

He swallowed hard, then dropped his gaze.

“At first,” he admitted. “At first, we heard them.”

The lieutenant went still. Even the wind sounded louder for a moment.

“And after?” the sergeant asked quietly.

The rail worker’s voice shrank to almost nothing.

“After,” he said, “no.”

That night, the survivors lay in cots inside a field hospital tent, canvas walls snapping softly in the cold. Outside, engines hummed, boots thudded, men moved. Inside, everything was slowed down to breathing and warmth and measured drops of water.

One woman was awake enough to track movement. Her eyes followed the nurse’s hands as the nurse poured a tiny amount into a spoon.

“Just a little,” the nurse said, soothing and firm. “Slow is good.”

The woman’s lips parted. The spoon touched her mouth. She swallowed carefully, as if water were still a gamble.

Her eyes filled, and she turned her face slightly away as if ashamed of tears.

The nurse sat on a stool beside her, watching.

“It’s okay,” she said.

The woman tried to speak. The words came out in broken English, thin and hoarse.

“Clean,” she whispered. “It is… clean.”

The nurse nodded, feeling something tighten behind her ribs.

“Yes,” she said. “It’s clean.”

The woman’s eyelids fluttered. Tears slid down her temples into her hairline. She whispered again, quieter.

“Because… it doesn’t hurt.”

The nurse held her breath.

Water isn’t supposed to hurt, she thought, and the thought felt like something you could only think in peace, something you could only think if you had never been trained to expect pain from the most basic things.

She didn’t correct the woman. She didn’t offer disbelief. She simply nodded and touched her wrist gently, a steady point of contact.

“I know,” she whispered, even though she didn’t. “I know.”

The young soldier from the rail yard stood at the tent entrance, helmet under his arm, watching the scene with a face stripped of bravado. He had told himself he was here for paperwork, for statements, for the lieutenant. The truth was simpler.

He needed to see them breathe again.

The nurse glanced up and motioned him in.

He stepped between cots carefully, boots quiet. He looked down at the woman whose sleeve he’d become a lifeline for, and his throat tightened.

“You’re safe,” he said, because it was the only sentence he trusted.

The woman’s eyes shifted toward him. Recognition flickered. She whispered something in German, then stopped, exhausted.

The nurse leaned in, listening, then looked up.

“She said,” the nurse told him softly, “you opened it.”

The young soldier’s chest tightened.

He nodded once. “Yes,” he said.

The woman’s eyes drifted closed, and her fingers relaxed against the blanket as if the admission allowed her body to let go of one more layer of fear.

In the days that followed, the Army did what armies did. It stabilized what could be stabilized. It moved survivors into processing camps with fences and watchtowers, but also scheduled meals, sanitation, medical checks, and something the freight car had made feel impossible.

Consistency.

Not everything healed. Some women coughed for weeks, their lungs remembering stale air. Some woke startled at night, minds still trapped in darkness. Some spoke only when necessary. Some didn’t speak at all. The interviews the Americans attempted were thin, full of gaps. Names missing. Units unclear. Faces blurred by dehydration and time.

Sometimes the only clear memory was the slam of the door, the click of the lock, and the thin light through roof slits, marking time like a cruel clock.

Then, one morning, another thing happened that should have been ordinary.

It wasn’t.

A supply truck arrived at the processing camp, tires crunching on gravel. Soldiers unloaded crates near the mess area. The air smelled like pine from trees beyond the fence and like coffee from the kitchen tent. The sky was pale, the kind of gray that made everything look washed clean.

The women watched without much expression. Food had become both comfort and threat. Their bodies didn’t always handle it well, and their minds didn’t trust anything unfamiliar.

A soldier opened a crate and began passing out bright yellow ears of corn, still warm. Some glistened with a faint sheen of butter. The smell carried, sweet and earthy, like summer had been folded into winter and delivered by hand.

The women stared.

It wasn’t relief that crossed their faces. It was suspicion.

A whisper moved down the bench line in German.

“Is that animal feed?”

Another woman’s mouth twisted, half joke, half defense.

“Pig food,” she murmured, because mocking first was sometimes the only way to protect your dignity.

An American private nearby overheard and laughed, not cruelly, just startled. He looked like a farm boy himself, cheeks ruddy, hands used to work.

“It’s corn,” he said, as if that answered everything. “Eat it. It’s good.”

The women didn’t move. Hunger alone wasn’t enough. Not after what their bodies had endured. Not after learning that the world could hide pain in ordinary places.

A nurse stepped closer and picked up an ear of corn. She broke off a piece and ate it herself, chewing slowly, swallowing, then holding up the rest like proof.

“It’s safe,” she said gently. “It’s just food.”

Still, no one reached out.

Then one woman, older than most, gray threaded through her hair, posture still rigid even after her body had nearly failed, lifted her hand. It shook slightly. She took the corn and turned it as if studying an unfamiliar object.

She smelled it. Warm. Sweet. No rot. No trick.

Her eyes flicked to the nurse, then to the American soldier, then back to the corn.

She took a bite.

The sound was small, a soft crunch, but it landed in the quiet like a bell.

Every face turned toward her. Every pair of eyes watched for a flinch, for sickness, for humiliation.

She chewed once, then again. Her eyes widened, not in fear, but in surprise.

Then, impossibly, she laughed.

Not loud. Not mocking. The kind of laugh that slips out when the body realizes, against all training, that something is not a threat.

“It’s sweet,” she said in German, the word sounding strange in her mouth, like a memory she hadn’t used in years.

Sweet moved through the group like electricity.

One by one, the women took bites. Some hesitated until the last moment, then surrendered with caution that bordered on reverence. Butter melted on fingers. Corn juice ran down chins. A few closed their eyes while they chewed, not because it was the best thing they’d ever tasted, but because it was normal.

Normal was what had been stolen first, quietly, over years of war.

One woman cried as she ate, wiping her face with the back of her hand as if ashamed.

The nurse crouched beside her. “It’s okay,” she said again, the same words she’d used in the hospital tent, the same steady tone.

The woman shook her head, trying to explain in broken English.

“Not… corn,” she whispered. “Not only corn.”

The nurse nodded anyway, understanding the shape of it. The corn wasn’t magic. It was ordinary. That was what made it unbearable and beautiful at the same time.

Across the yard, the young soldier watched again, because watching had become his way of holding reality in place. He saw suspicion soften into relief. He saw how a bite of warm food could crack open a part of the body that had been braced for pain.

He thought of the woman in the hospital tent whispering, because it doesn’t hurt.

He understood something he hadn’t understood before.

Relief can arrive so suddenly the body doesn’t know where to put it. Safety can feel like shock when you’ve lived too long expecting harm.

That evening, he wrote a letter home and chose the smallest truth he could bear to send.

He wrote about corn.

He wrote about a woman who took one bite like she was tasting a future she hadn’t believed existed.

He didn’t describe the freight car in detail. He couldn’t. He folded the paper neatly and sealed it, as if neatness could keep the war from leaking through the envelope.

The official reports would later reduce the freight car to a brief incident. Discovered in a rail yard. Survivors treated. Casualties noted. Cause unclear due to missing documentation. There would be no single villain, no clean chain of command, no satisfying conclusion.

Neglect rarely comes with a signature.

The rail worker would disappear back into the wreckage of his country, carrying his fear and his excuses and the truth that he had heard them at first.

The lieutenant would file the papers and move on, because war endings were crowded with stories and the world’s attention had limits.

But the women would remember.

They would remember the stale air and the thin light and the feeling of time dissolving inside a sealed box. They would remember the moment fresh air hit their faces like a shock. They would remember water that didn’t hurt. They would remember corn that tasted sweet and normal and impossibly safe.

Years later, one of them would fill a glass of water in a quiet kitchen and watch the clarity, the light through it, the way it sat without menace. She would drink slowly, and her hand would tremble almost imperceptibly, not from weakness, but from memory.

She would not waste water. She would not waste food. She would notice temperature and taste the way people notice sacred things.

And sometimes, without warning, she would pause after the first sip.

Not because she was weak.

Because her body remembered what it had once been forced to forget.

Because the most brutal parts of war are not always the loud ones.

Sometimes they happen in sealed spaces, in abandoned yards, in the quiet minutes when nobody turns a lock, and survival becomes a story the world nearly misses.

News

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load