My daughter texted me, “I’m taking you to court, selling this house, and you need to move out now.”

No greeting. No hesitation. Just a sentence that landed like a judge’s gavel. I read it twice, then a third time, because part of me still believed there had to be a softer meaning hidden between the words. There wasn’t. The message was ice-cold, final, written with the certainty of someone who’d already rehearsed the ending.

She followed with another line, as if she couldn’t resist driving the blade in deeper. “You’ll have nowhere else to go.”

I set the phone down on the kitchen table and stared at the wood grain like it might offer instructions. The afternoon sun was coming in at an angle, catching dust in the air, turning the room almost peaceful. That contrast was what made it hurt. The house was quiet the way it always was on a weekday, the way it had been since my husband died and my life settled into smaller sounds: the tick of the clock in the hallway, the hum of the refrigerator, the occasional creak when the boards adjusted to temperature.

I didn’t call her back. I didn’t text an argument. I didn’t do any of the things a person is supposed to do when their own child threatens to take their home.

I stayed quiet.

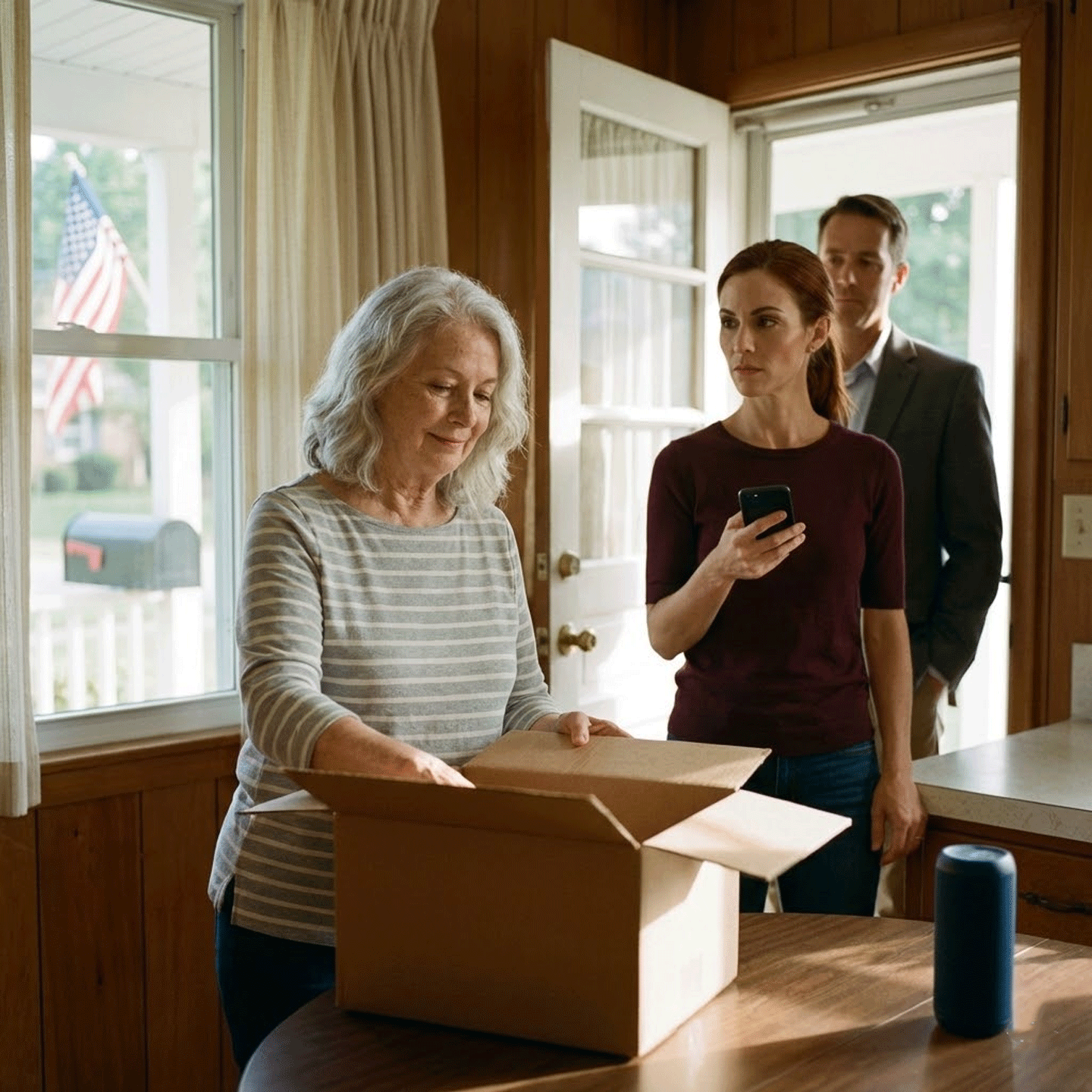

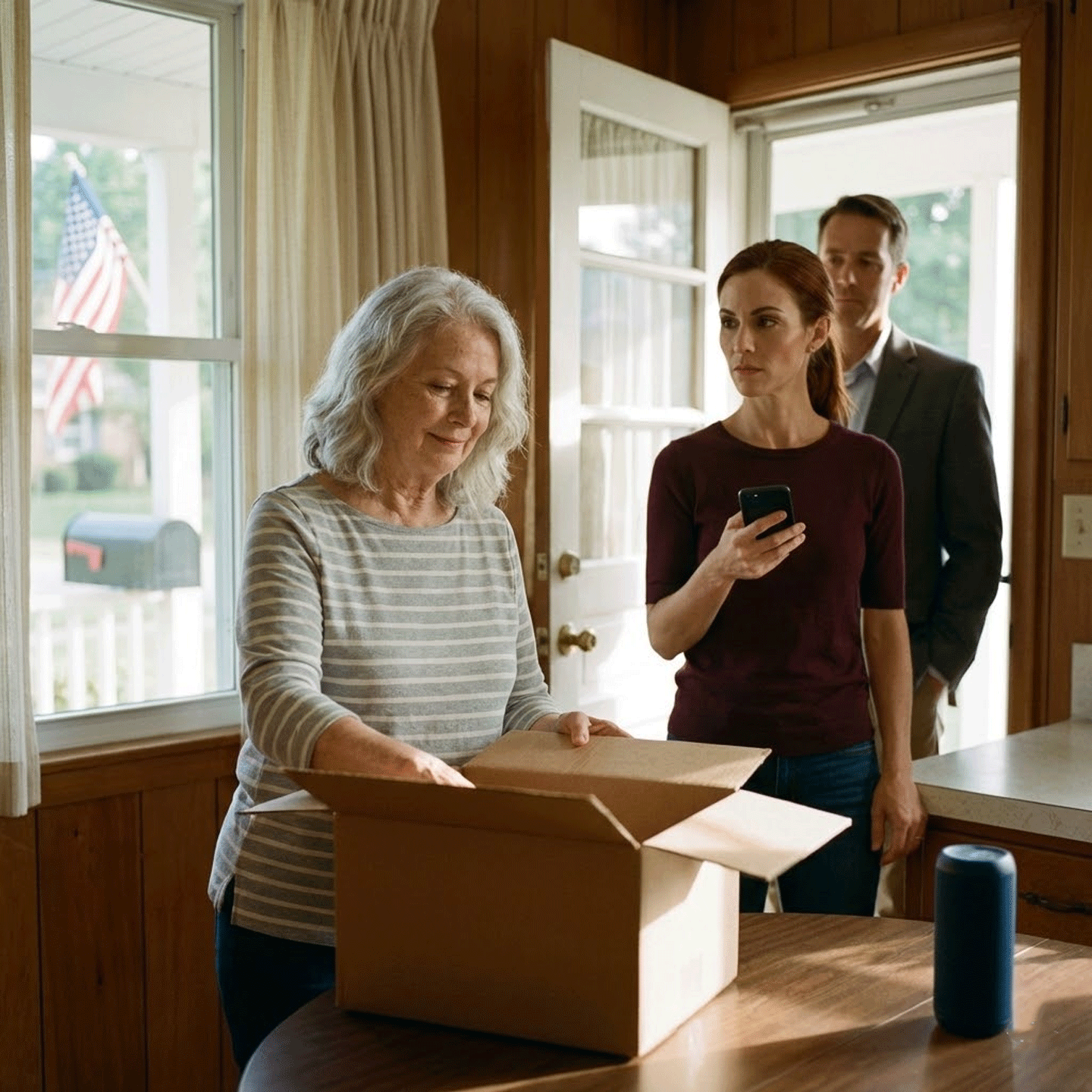

Then I started packing.

Not frantically, not dramatically. I did it the way you fold laundry when you don’t want to think one item at a time, careful and steady. A cardigan into a box. A stack of photos into tissue paper. A book I’d been reading, slid into a tote bag. I moved through my own rooms like a guest preparing to leave, like I’d already been told I didn’t belong. If anyone had looked through my window, they would’ve seen exactly what Jennifer wanted the world to see: an old woman complying.

But there was one thing she didn’t know.

The house had already been sold.

The paperwork was signed and complete.

And the secret behind it was going to force our entire family to change course, faster than anyone could react.

I had lived in that house for sixty-three years. I’d called it home so long my body seemed built to its shape. I knew which floorboard complained near the living room entrance, the one Robert always meant to fix but secretly liked because it announced someone coming in. I knew the hairline crack in the ceiling above the dining table, a harmless scar from an ancient winter when the house had settled and never quite returned to perfect. I knew the exact time the late-afternoon light would fall across the kitchen tile and turn everything honey-colored, even on days when my heart felt dark.

Robert and I bought the place in 1962, when the neighborhood was still young. Back then, the street felt like possibility. New lawns. Fresh paint. Young couples hauling furniture through open doorways, calling to each other over the sound of hammering. The local hardware store still carried everything you needed for a first home and always smelled like wood shavings and metal. We were newly married and brave in that naïve way newlyweds are, convinced that love and a steady paycheck would be enough to build a life.

We raised our daughter, Jennifer, there. Christmas mornings with wrapping paper piled high. Birthday cakes with uneven frosting because a small child insisted on helping. The day she graduated high school, the cap thrown in the air in front of the maple tree by the sidewalk. The day Robert taught her to drive and I stood on the porch pretending not to worry as they lurched down the street in our old sedan.

When Robert passed five years ago, the house became more than shelter. It became a museum of a marriage. His reading chair stayed by the front window, angled toward the light the way he liked it. His tools still hung in the garage, arranged with the careful logic of a man who believed order was a form of respect. Some mornings I’d walk past the hallway mirror and expect to see him behind me, tall and steady, asking if I wanted coffee. Sometimes, if I opened the closet too quickly, I’d catch the faintest trace of his aftershave, and my throat would tighten before my mind could prepare.

The house held him everywhere. Not as a ghost, not as a haunting, but as memory made physical. I could stand in the living room and still hear his laughter during football games, his voice calling out scores, his teasing when I pretended not to care. I could stand at the kitchen sink and remember his hands around my waist from behind while I washed dishes, the simple intimacy of a life built on small, repeated tenderness.

Jennifer had always been… complicated. Even as a child, she wanted what she wanted, and she wanted it now. If she didn’t get it, the disappointment didn’t pass like weather. It turned into a performance. Tantrums that lasted longer than they should. The kind of sulking silence that punished everyone in the room until someone gave in just to restore peace. She learned early that affection could be withdrawn like a privilege and used as leverage.

As she got older, those tactics didn’t disappear. They evolved. She learned to sound reasonable while pushing boundaries. She learned to smile while demanding. She learned how to make her selfishness look like concern, the way some people can make a lie look like love.

When she was twenty-eight, she married Derek. He was a real estate developer with slicked-back hair and a confident smile that never quite reached his eyes. He shook hands too firmly and spoke in polished phrases, like every conversation was a negotiation. I tried to welcome him. I told myself the job of a mother was to support, to keep the door open, to give the benefit of the doubt.

But something about him set my nerves on edge. A subtle predatory patience. The way he looked at rooms the way other men looked at money. The way he laughed at jokes a beat too late, like he was calculating whether laughter would benefit him.

For years, Jennifer and Derek lived the life she wanted people to envy. Big house in the suburbs. Luxury cars. Expensive vacations displayed online like proof of success. Jennifer posted photos of ocean sunsets and fancy dinners, smiling with a glass in her hand, as if the point of living was to be seen doing it.

She visited me occasionally, but those visits grew shorter over time, more transactional. She’d ask about my health and my finances in the same breezy tone, as if both were interchangeable topics. She’d mention my will like it was the weather. “You updated it, right?” she’d say, smiling. “Just to be safe.”

Eight months before everything exploded, her visits began to increase. At first, I told myself it was grief. Maybe losing Robert had shaken her more than she admitted. Maybe she’d realized time wasn’t infinite and wanted to repair something between us. I wanted to believe that. I wanted my daughter back, not the version of her that visited like a banker.

But the way she moved through the house told the truth.

She walked slowly from room to room, touching things lightly, not with nostalgia but with appraisal. She stood in the dining room doorway, eyes narrowing, as if she was already imagining new paint and staged furniture. She paused in the hallway and measured the space with her gaze. Sometimes Derek joined her, hands in his pockets, and they spoke in half sentences, the way people do when they don’t want you to understand.

“Mom, this place is getting too big for you,” Jennifer said one afternoon, trying to make it sound like a kindness. “Don’t you want to downsize? Wouldn’t it be easier?”

I smiled and changed the subject, but I wasn’t blind. I saw the hunger under her concern.

Then she started mentioning memory care facilities.

“Just for when you’re older, Mom. Just to be prepared.”

I was seventy-eight and sharp as a tack. I balanced my own checkbook. I drove myself to the grocery store. I volunteered at the library twice a week, and the young coordinator there trusted me to manage inventory and schedules. I remembered birthdays. I remembered passwords. I remembered everything that mattered. When Jennifer said “memory care,” she said it the way someone says “inevitable.”

Three months ago, she brought Derek and a man in an expensive suit she introduced as a family attorney. They sat in my living room Robert’s living room and talked about protecting my assets and estate planning. The lawyer had papers. Jennifer had carefully prepared talking points. Derek wore that same mild, satisfied smile.

I served them tea because my mother raised me to be polite even when my stomach turned.

The lawyer used words like “trust,” “security,” “peace of mind.” Jennifer squeezed my hand and looked at me with practiced concern. Derek nodded like he approved of compassion as a strategy.

They wanted the house.

Not after I died. Now.

They wanted me to sign it over, move somewhere smaller, somewhere “safe.” Somewhere they controlled. Somewhere my independence would quietly disappear behind locked doors and friendly nurses.

I told them I’d think about it.

They left the paperwork on my coffee table like a trap.

After they drove away, I sat in Robert’s chair and stared at those documents until the words blurred. My hands weren’t shaking. Not yet. But something cold settled in my chest, like a stone I couldn’t swallow and couldn’t spit out.

Two weeks later, Jennifer called.

“Have you thought about what we discussed, Mom?”

“I’m still considering,” I said.

Her voice shifted, just slightly. The warmth thinned. The patience snapped into something sharper.

“At your age, these decisions shouldn’t wait,” she said. “What if something happens to you? What if you become incapacitated? Derek and I would have to go through probate. It would be such a mess. We’re trying to help you avoid that.”

I’m sure you are, I thought.

But I said, “I appreciate your concern.”

After that, the calls came more often. The visits became more insistent.

And then last Tuesday, the truth finally came out without makeup.

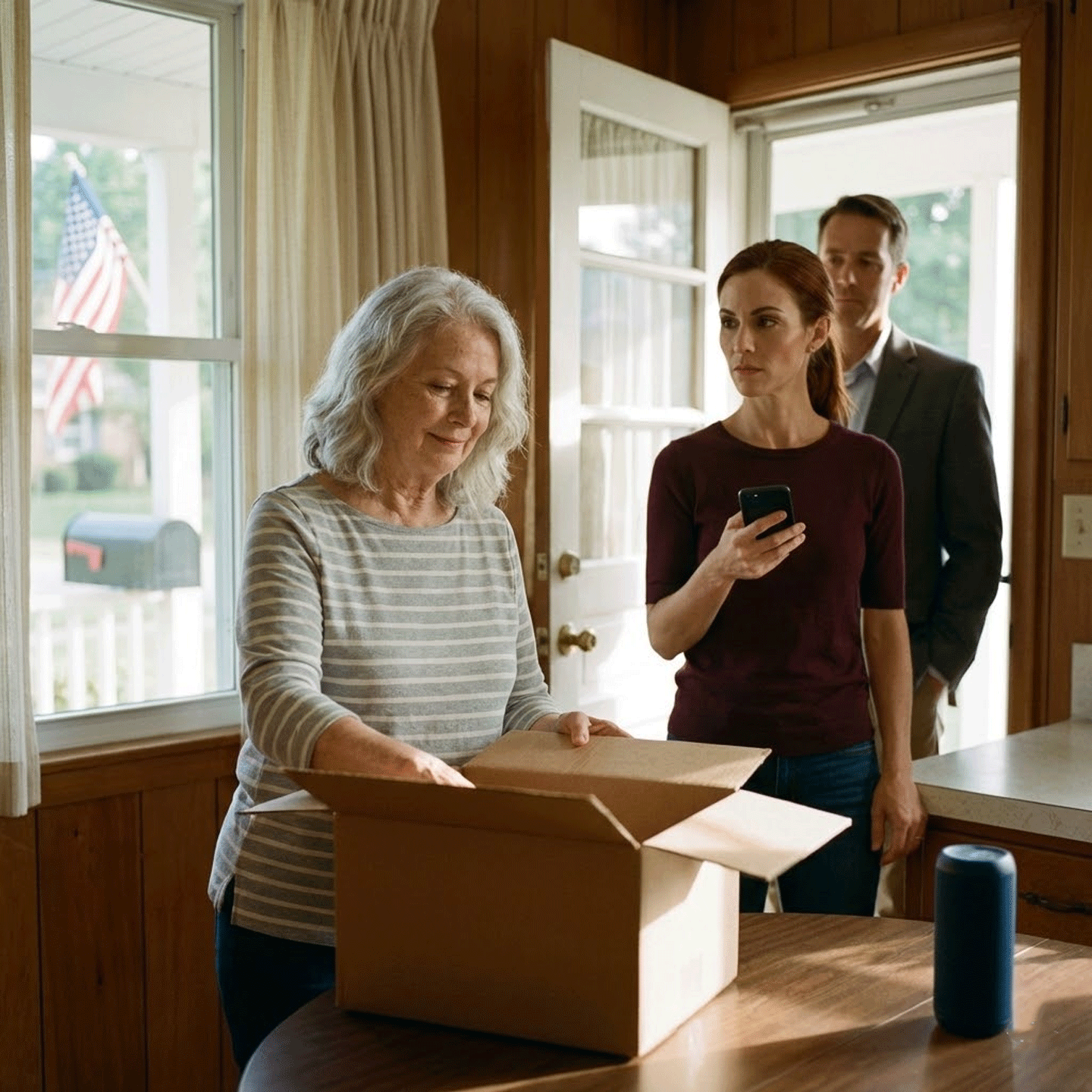

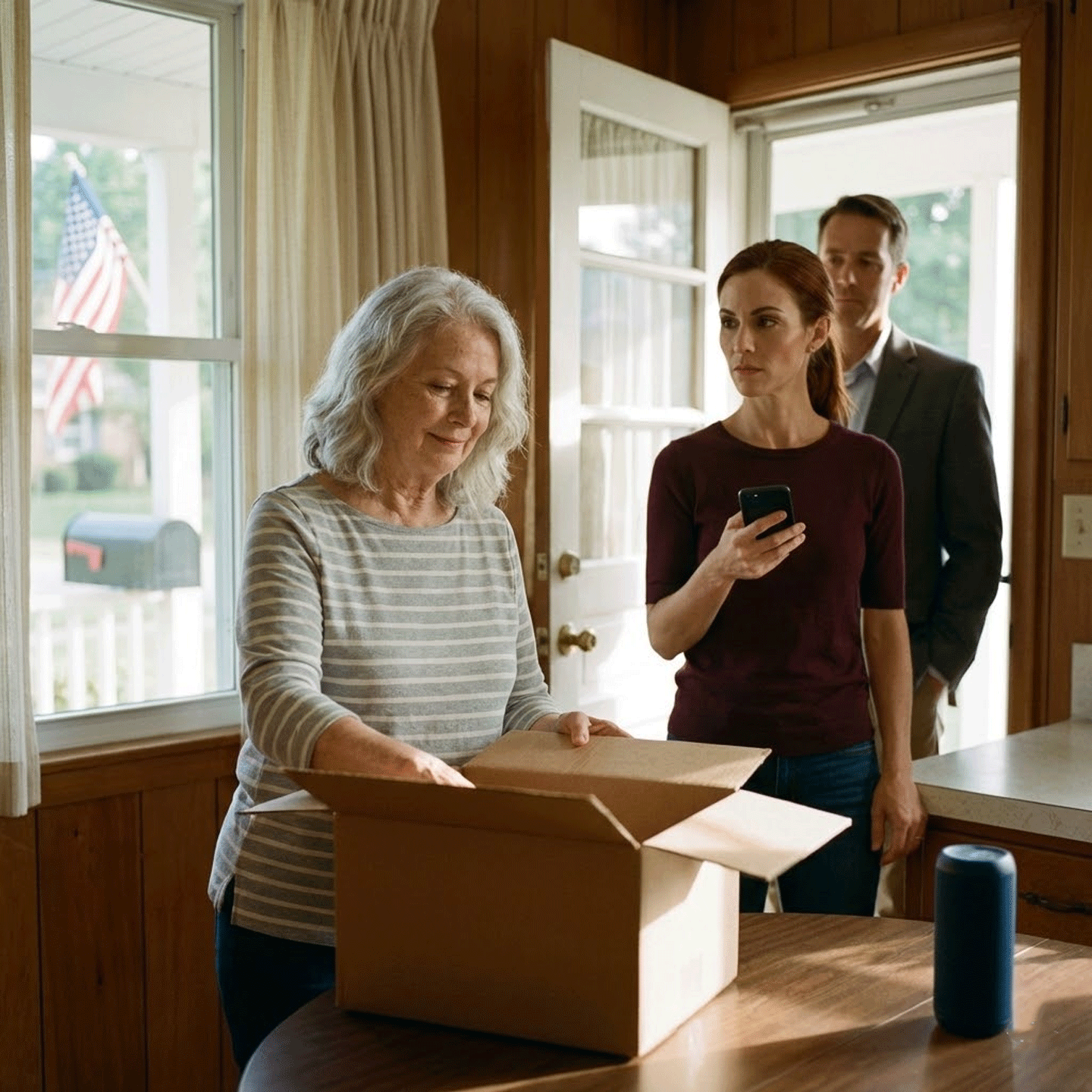

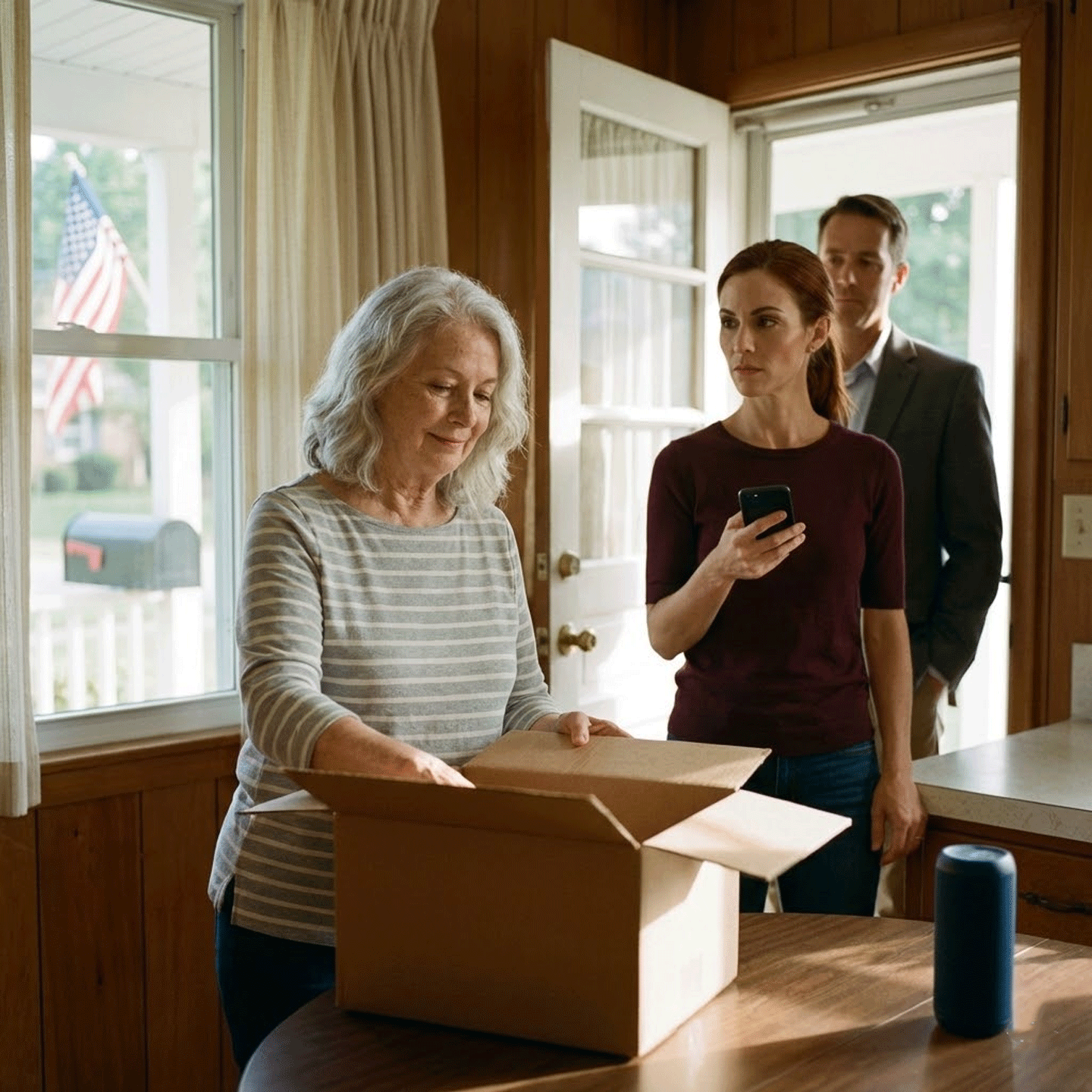

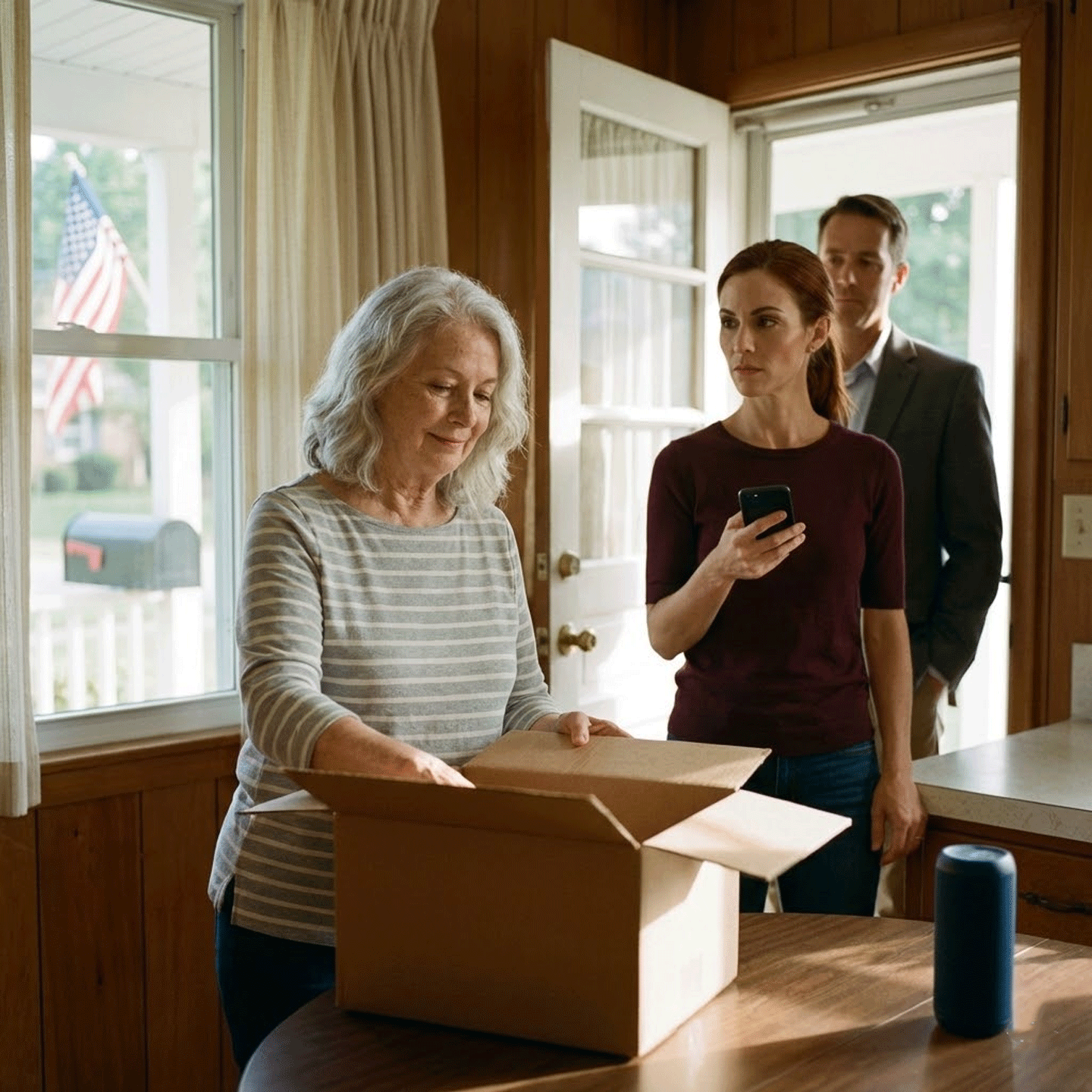

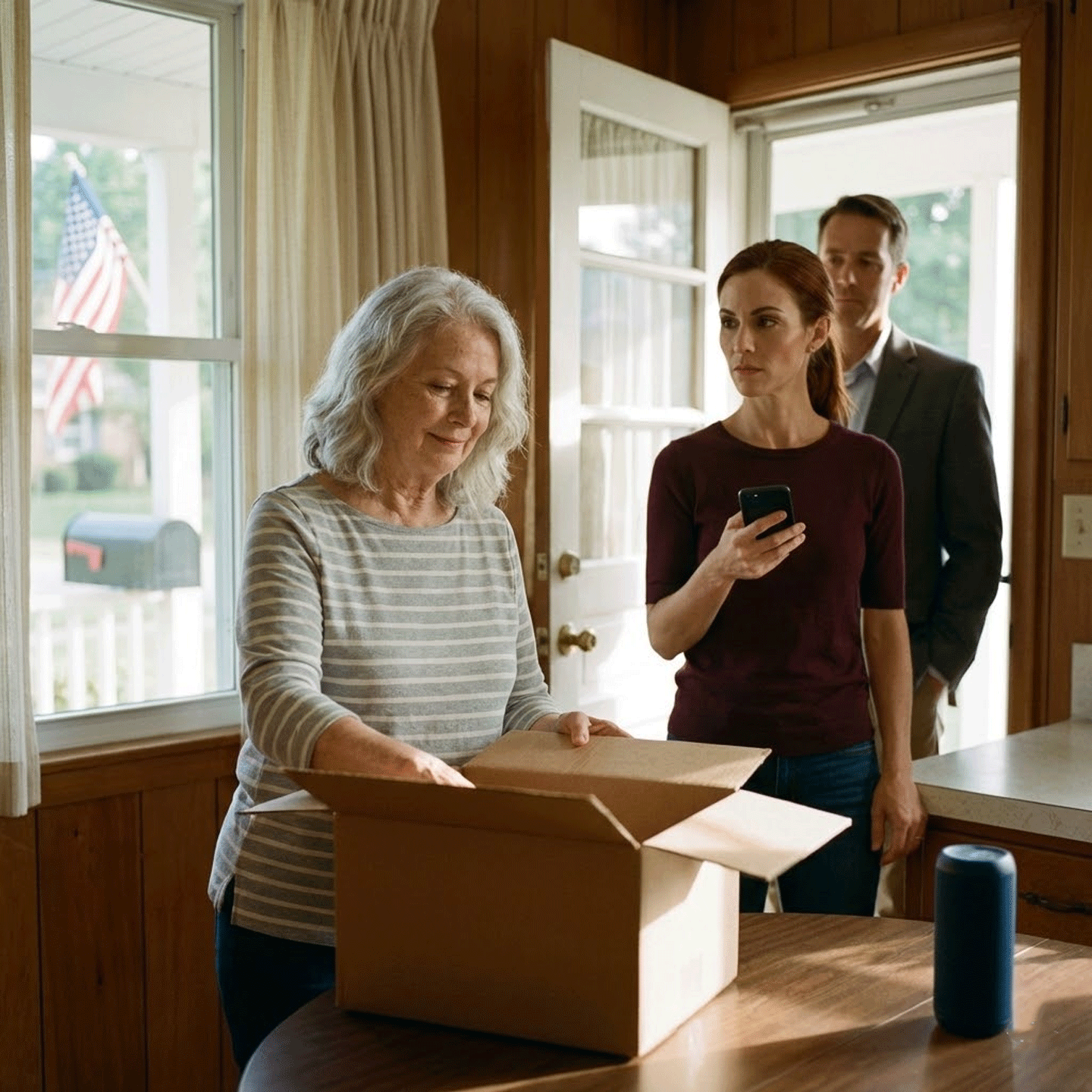

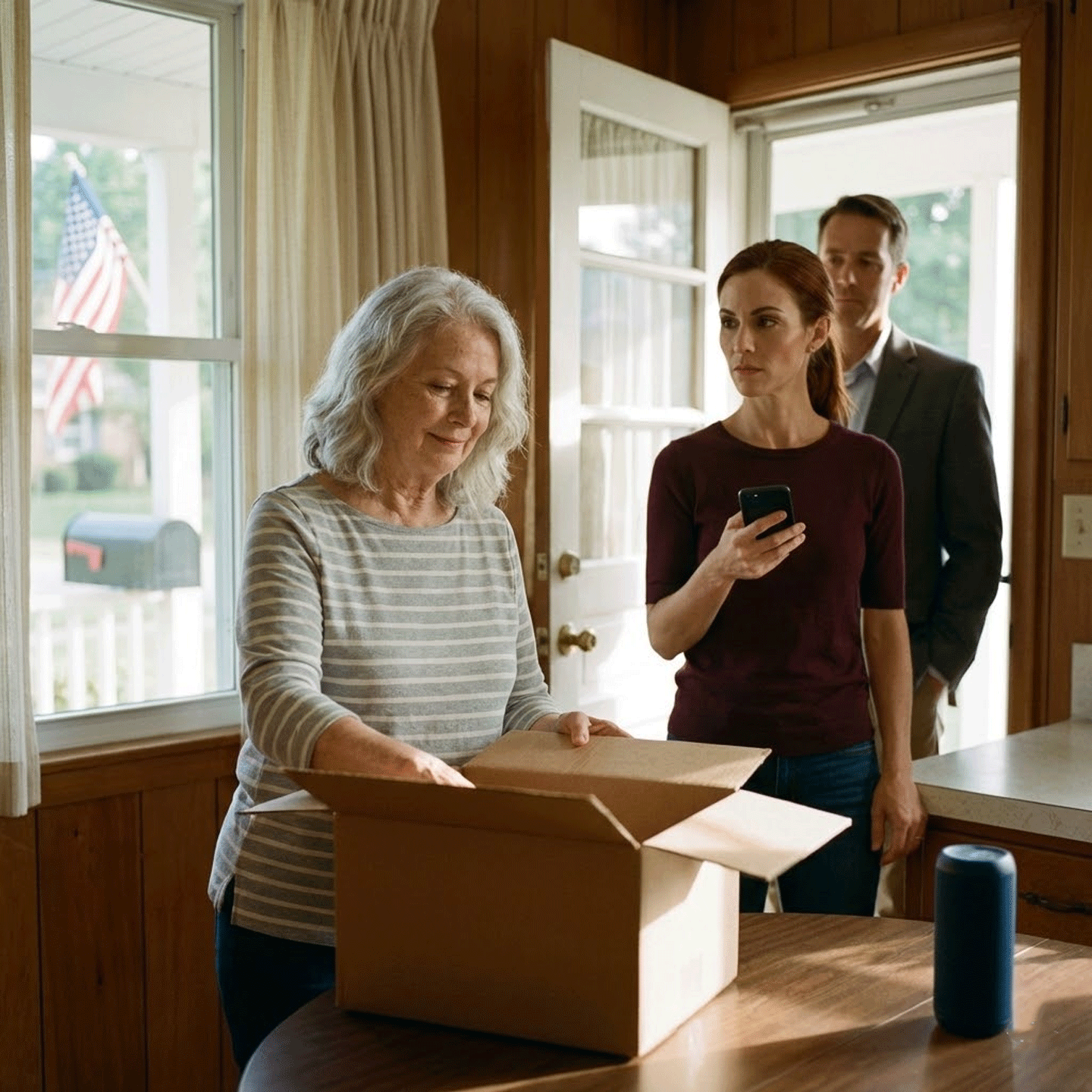

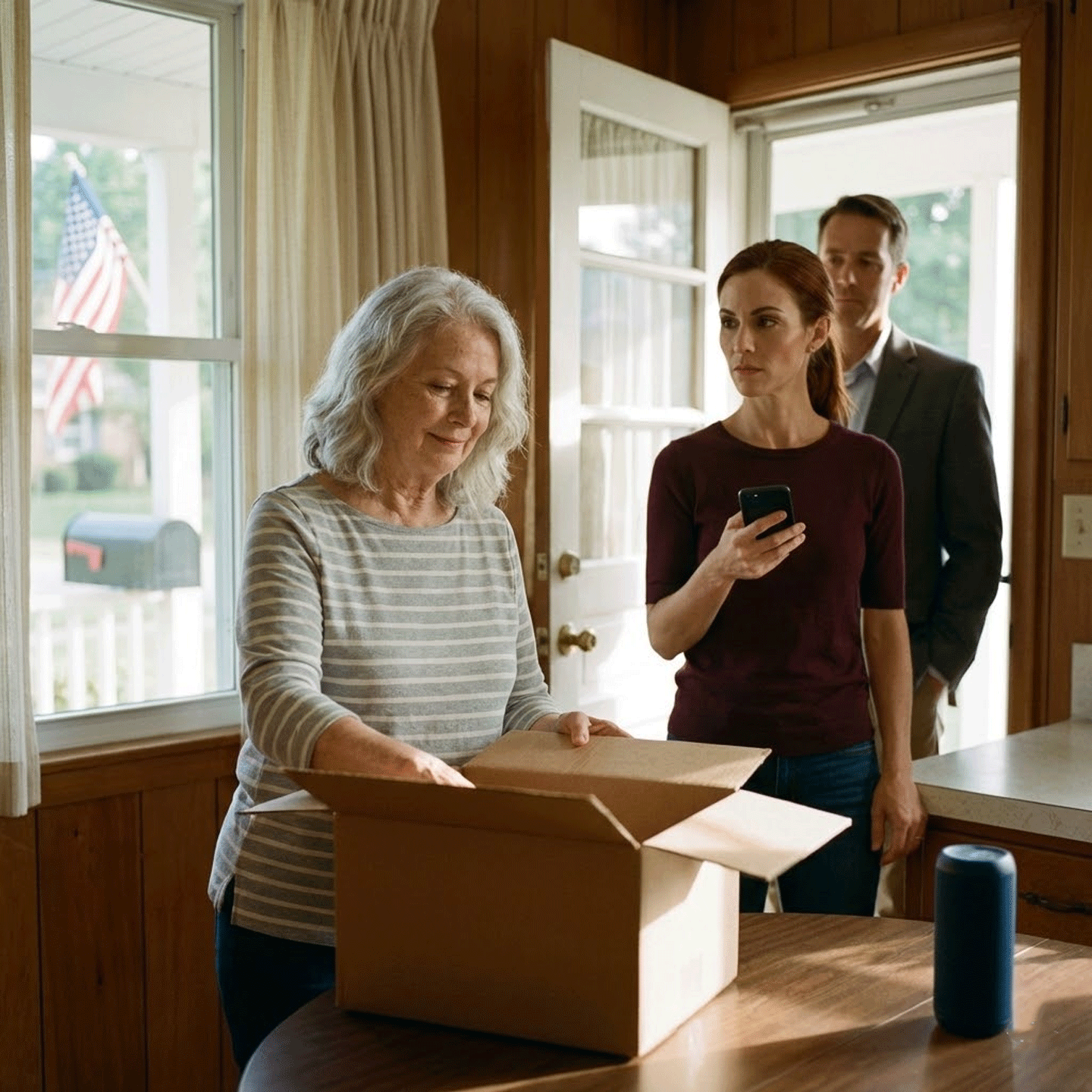

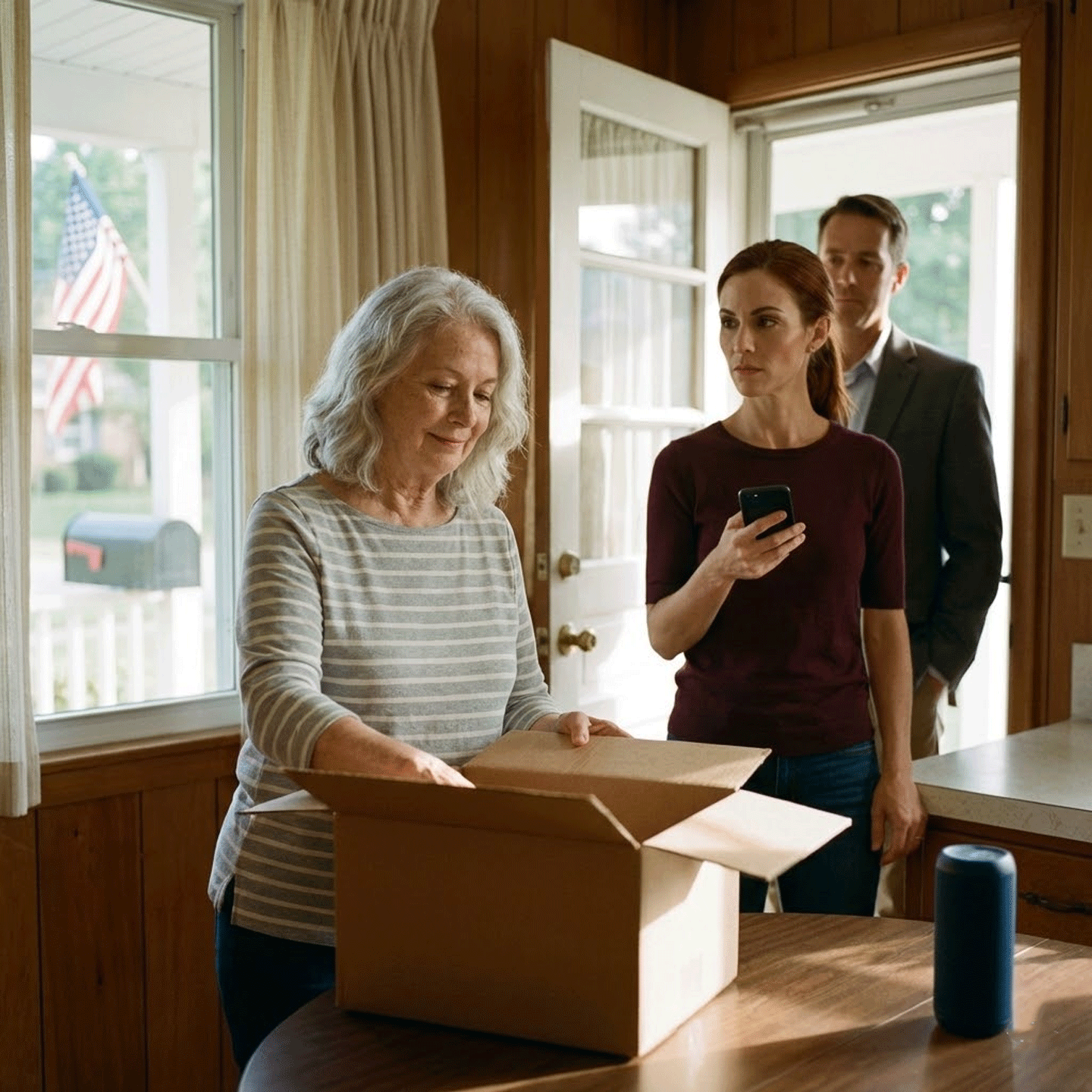

Jennifer arrived unannounced with Derek. No warning. No courtesy call. They came into my kitchen like they owned it.

“Mom,” Jennifer said, and her voice had none of its usual false sweetness. “We’ve been patient. We’ve tried to do this the easy way, but you’re being stubborn and frankly irresponsible.”

I set my coffee cup down carefully. “Irresponsible?”

Derek stepped closer. “We’ve consulted with our attorney. Given your age and your diminishing capacity ”

“My what?”

Jennifer’s face hardened. “We’re filing a petition for conservatorship. We have documentation of your declining mental state. We’ll get control of your finances, your property, everything, and then we’re selling this house.”

I stared at her, trying to find the child I once knew behind the adult standing in my kitchen. My daughter. My only child. The baby I held on my hip while I cooked. The teenager I waited up for at night, pretending not to worry while every mother’s instinct screamed.

She leaned in close.

“We’re taking your house through the courts and we’re selling it,” she whispered. “Start packing your things and get out.”

I smiled.

I didn’t mean to. It happened because something inside me snapped into a strange clarity. The smile wasn’t joy. It wasn’t forgiveness. It was the expression you make when someone threatens to take something from you that they don’t realize they can’t touch.

Jennifer mistook it for weakness. Or maybe she mistook it for surrender.

She and Derek left as quickly as they came, satisfied they’d finally shown their power.

When the door closed behind them, I sat at my kitchen table for a long time. The late-afternoon sun slanted through the windows, casting long shadows across the linoleum Robert and I installed together decades ago. My hands began to shake.

Not from fear.

From rage.

How dare she? How dare they walk into my home and threaten me like I was a child. Like I was incompetent. Like my life was something they could file paperwork against and take.

But beneath the anger was a colder fear that crept in quietly, like winter air through a crack.

What if they could do it?

I’d read stories. Elder abuse. Adult children manipulating the legal system. Conservatorships obtained with the right lawyer, the right “expert,” the right narrative. I imagined myself in a sterile facility with beige walls and scheduled meals, my freedom reduced to visiting hours. I imagined Jennifer selling everything Robert and I built, and smiling for photos like it was her success.

The fear threatened to paralyze me.

Then I looked at the photo on my refrigerator. Robert in his Navy uniform, young and strong, eyes steady. He’d stormed beaches in the Pacific. He’d built a business from nothing. He never backed down from a fight, especially not when someone he loved was threatened.

What would Robert do?

He’d fight back. Not with hysteria. With strategy.

I stood up. My hands stopped shaking.

If Jennifer wanted a war, she’d get one.

But it would be fought on my terms.

That night, I sat at my computer and researched conservatorships, elder abuse, property law. I read until the words blurred, until my eyes ached, until the outline of their plan became painfully clear.

Jennifer and Derek were building a case. A pattern of “concern.” A trail of alleged forgetfulness. A story about “declining mental capacity.” They’d find someone with credentials willing to sign off on suspicion, someone who would call my refusal to cooperate “proof” that I was unstable.

Then they’d file. Then they’d stand in front of a judge and present their version of me: confused, vulnerable, in need of protection.

Once they had conservatorship, selling the house would be easy. They’d say it was in my best interest to move into assisted living. The money from the sale would go into a trust “for my care,” and then it would disappear through fees and expenses and legal paperwork, all of it perfectly dressed in official language.

It was sophisticated. It was predatory. And it happened to people every day.

But I had one advantage they didn’t expect.

I saw it coming.

By dawn, I had a plan.

If they wanted to claim I was incompetent, I’d need proof I wasn’t. A full medical evaluation. A cognitive assessment. Documentation from my physician establishing my mental acuity.

But that was defense.

I needed offense.

The house was the target. Which meant the house could also be my weapon.

If I didn’t own it, they couldn’t take it.

The idea was simple enough to feel brutal. It also felt like a door locking into place.

The question was who to trust.

I thought about “family” and felt a bitter laugh rise in my throat.

Then I thought about Tom.

My grandson. Jennifer’s son from her first marriage. A marriage that ended when she cheated with Derek. Tom was twenty-five now, a teacher in Oregon. He called me every Sunday, without fail. He visited when he could, and when he did, we talked for hours. Books, politics, life. His students. My garden. The state of the world. The state of our hearts. He was nothing like his mother. He had Robert’s steadiness, his integrity. And Jennifer always resented our closeness, as if love was a limited resource she needed to ration.

At six in the morning, I called him anyway.

He answered on the second ring, voice soft with sleep but immediate concern.

“Grandma? Is everything okay?”

Hearing his voice made my eyes sting.

“Tom,” I said, “I need your help. And I need you not to tell your mother about this conversation.”

There was a pause.

“What’s she done now?” he asked.

Smart boy. He didn’t ask if I was overreacting. He didn’t ask if I’d misunderstood. He knew his mother.

“She’s trying to take the house,” I said. “She’s trying to take everything.”

Another pause, and then his voice hardened in a way that made my chest loosen. Not because I wanted anger, but because I wanted certainty.

“Tell me what you need,” he said.

Three days later, I sat in the office of Margaret Chen, the attorney Tom recommended. The space was modest but professional, walls lined with law books, certificates arranged neatly, a family photo on the desk that radiated quiet stability. Margaret herself had sharp eyes and a calm manner, like someone who didn’t panic because she’d seen worse and survived it.

“Mrs. Patterson,” she said, reviewing my notes, “your daughter hasn’t actually filed for conservatorship yet.”

“Not yet,” I confirmed. “But she’s threatened to, and she’s building a case.”

Margaret nodded slowly. “The best defense is preparation. First, get a complete medical evaluation physical and cognitive. We establish a baseline showing you’re of sound mind and body. Second, document everything. Every conversation, every threat, every visit. Dates, times, witnesses.”

“I started a journal,” I said, and slid my notebook across the desk. The pages were filled with careful handwriting. Not dramatic. Not emotional. Just facts. The way you build a wall one brick at a time.

Margaret smiled. “Good. Now, about the house. You said you want to protect it.”

“I want to transfer ownership,” I said. “To my grandson, Tom, as a gift.”

Margaret’s expression turned cautious. “I need to be clear. Transferring property to avoid a conservatorship could be challenged. If your daughter can prove you did this specifically to thwart her petition, a judge might reverse it.”

“I’m doing it now,” I said, leaning forward. “Before any petition is filed. I’m a competent adult making a decision about my own property. I want to gift my house to my grandson. That’s legal.”

“It is,” Margaret said. “But timing matters. If she files within days ”

“Then we document my reasoning,” I interrupted. “Tom has always been close to me. He’s responsible. I’m keeping the family home in the family. That’s a reasonable choice.”

Margaret studied me for a long moment.

“You’re sharper than most people half your age,” she said. “All right. We’ll do this properly. Deed transfer documents. Witnesses. Notarization. Everything by the book.”

“Tom’s flying in tomorrow,” I said.

The next week felt like a race against a storm cloud.

I scheduled an appointment with Dr. Morrison, my physician of years. I sat in the familiar exam room, the paper on the table crackling under me, the smell of antiseptic and hand sanitizer in the air. Dr. Morrison reviewed my results with a frown that turned into something like satisfaction.

“Helen,” he said, “you’re in better health than most sixty-year-olds. Your memory, reasoning, judgment completely normal. Better than normal, actually.”

“Would you be willing to document that?” I asked.

He looked up sharply. “Is someone claiming otherwise?”

“My daughter,” I said quietly.

His jaw tightened. He’d known Jennifer since she was a child.

“I’ll write the most detailed medical assessment of my career,” he said. “And if anyone tries to twist this, I’ll show up in court myself.”

When Tom arrived, I felt the kind of relief you don’t realize you’ve been starving for. He hugged me carefully, as if he was afraid I might break. I didn’t. I hugged him back hard enough to let him feel the steel under my skin.

We sat in my living room Robert’s living room and I told him everything. He listened without interrupting, his face growing darker.

“She’s really doing this,” he said when I finished. “She’s really trying to steal your house.”

“She thinks she’s entitled to it,” I said. “And she’ll use whatever legal mechanism she can.”

“What do you need me to do?” he asked.

“Accept a gift,” I said.

He shook his head. “Grandma, I can’t take your house.”

“You’re not taking it,” I said. “I’m giving it to you. And you’re protecting it from your mother.”

I leaned forward. “This house is my last connection to your grandfather. I won’t let Jennifer sell it. I won’t let her erase what we built. Will you help me?”

Tom took my hands. His grip was steady. His eyes were clear.

“Of course,” he said. “Of course I will.”

We arranged it so I retained a life estate. I would live in the home as long as I wanted. Tom would own it legally, but he wouldn’t be able to sell it or profit from it while I was alive. It was protection, not a payout. It was legacy, not greed.

On Friday morning, we met at Margaret Chen’s office. The deed transfer was executed with precision. Witnesses present. Everything notarized. Everything done with a careful thoroughness that made me feel, for the first time in weeks, like I could breathe.

By noon, the house at 347 Maple Street was legally owned by Thomas Patterson Jr., with Helen Patterson retaining life estate rights.

Margaret filed the deed with the county recorder that afternoon.

“It’s done,” she told me by phone. “The transfer is public record.”

I thanked her and hung up.

Then I sat in Robert’s chair and waited.

It took exactly four hours.

At 4:47 p.m., Jennifer’s car screeched into my driveway. I know the time because I checked my watch. She didn’t knock. She had a key. The door flew open and she stormed into my living room, face twisted with fury.

“What did you do?” she hissed.

Derek was right behind her, holding his phone. His eyes were narrowed, his mouth tight.

“She transferred the house,” he said. “She gifted it to Tom. It’s in the public records.”

Jennifer’s hands shook with rage. “You… You actually How could you?”

“Careful,” I said quietly. “I’m recording this conversation.”

I held up my phone. The recorder app was open. The little red dot glowed like a warning. Both of them froze.

“You wanted evidence of my mental state,” I continued. “Here it is. I’m competent enough to protect my assets from thieves, even when those thieves are my own daughter.”

Jennifer’s face went white, then red. “You can’t do this. We’ll challenge it. We’ll prove you were manipulated. That Tom coerced you.”

“With what evidence?” I asked. “Dr. Morrison certified I’m in excellent mental health. Margaret Chen will testify. Tom wasn’t even in the state until two days ago. What will you prove?”

Derek grabbed Jennifer’s arm. “We need to talk to our lawyer,” he muttered.

They left without another word. But Jennifer turned back at the doorway, and the look she gave me wasn’t sadness or disbelief.

It was hatred.

“This isn’t over, Mother,” she said.

“No,” I replied, my voice calm. “It isn’t.”

After they drove away, I stood in the quiet living room and listened to the house settle. The walls didn’t change. The floorboards didn’t protest. The sun still moved across the carpet the way it always had.

But something inside me had shifted into a colder, steadier shape.

Jennifer had declared war.

And now, legally, she no longer knew what she was fighting for.

The weekend passed like a held breath.

I moved through Saturday and Sunday the way you do when you’ve heard a rattlesnake in the grass but you can’t see exactly where it is. I cooked. I watered the plants. I folded laundry. I answered a neighbor’s wave from the driveway. I watched an old movie on TV and couldn’t tell you a single thing that happened in it. Everything I did was ordinary on the surface, but underneath, my mind kept circling the same truth: Jennifer and Derek were regrouping. They weren’t the type to accept a closed door without trying a window.

I slept in fragments. I’d drift off, then wake at two in the morning, listening. The house had its usual night sounds pipes ticking as they cooled, the soft whir of the furnace, the distant rush of a car on the main road but my nerves interpreted everything as warning. I hated that. I hated that they could reach into my peace and rearrange it.

On Monday morning, my phone rang from an unknown number.

“Mrs. Patterson,” a man’s voice said, smooth and confident. “This is Richard Kramer from Kramer and Associates. I represent your daughter, Jennifer Patterson Hullbrook. I’d like to discuss the recent property transfer you executed.”

I didn’t sit down. I stayed standing by the kitchen counter, one hand resting on the edge like I needed the contact to keep myself steady.

“I’m represented by counsel,” I said. “Margaret Chen. Contact her.”

There was a pause, as if he wasn’t used to being denied access to a target.

“Mrs. Patterson,” he continued, “I think we can resolve this without getting attorneys involved.”

“We’re already involved,” I said.

He made a small sound that might have been a sigh, might have been annoyance. “I’m simply trying to help you avoid unnecessary conflict.”

“The unnecessary conflict started when my daughter threatened to take my home,” I replied. “Goodbye, Mr. Kramer.”

I hung up before he could respond.

For a moment, I just stood there, staring at the phone as if it might ring again immediately. Then I called Margaret and told her exactly what he’d said, exactly how he’d tried to slip around her.

“Predictable,” she said. “They’re testing for weakness. Don’t speak to them or their attorney without me present. And Helen…”

“Yes?”

“Expect them to escalate.”

Margaret didn’t dramatize. She didn’t need to. Her calm carried the weight of experience, the kind that comes from seeing how far people will go when money is involved.

By midafternoon, I heard tires on gravel.

I looked out the front window and saw Jennifer’s car in the driveway, Derek’s behind it. Two strangers stepped out as well one a middle-aged woman in business attire, the other an older man carrying a briefcase like it was an extension of his arm.

Jennifer didn’t knock politely. She pressed the doorbell, then pressed it again, impatient, like she didn’t believe time applied to her when she wanted something.

I opened the door, but I didn’t step back. I stood in the doorway like a boundary made of bone.

“Mom,” Jennifer said, voice tight with manufactured restraint. “This is Dr. Patricia Whitmore, a geriatric psychiatrist. And this is Arthur Levenson, our family attorney. We need to talk.”

The psychiatrist’s expression was professionally gentle, the kind that could be either compassion or camouflage. Levenson looked like someone who’d spent decades sitting at conference tables, nodding along while other people signed away their rights.

“We don’t need to talk,” I said.

Derek took a half step forward, already trying to claim space. “Helen, we’re trying to help you. This property transfer was impulsive. It’s a clear sign of diminished capacity.”

I felt something cold and sharp slide through me, not fear, but the realization of just how quickly they’d chosen their narrative. They weren’t even pretending anymore. They were labeling me. Stamping me. Turning me into a story that served them.

Dr. Whitmore spoke softly. “Mrs. Patterson, your daughter is concerned about your welfare. If you’re making major decisions, giving away significant assets ”

“I gave my house to my grandson,” I said clearly. “After careful consideration and legal consultation. That’s not impulsive. That’s estate planning.”

Levenson clicked open his briefcase. “Mrs. Patterson, we have reason to believe you may not be fully capable of making these decisions on your own. Your daughter has documented concerning incidents. We have witnesses.”

“Witnesses,” Jennifer repeated, as if the word itself should intimidate me.

Levenson looked down at a paper, then up at me. “Your neighbor, Mrs. Rodriguez, reports you forgot her name last month. Your hairdresser says you missed an appointment and didn’t remember making it. Your pharmacy called you repeatedly about a prescription you didn’t pick up.”

My stomach tightened, not because any of it was true in the way they meant, but because I could see exactly what they were doing. They were taking the harmless imperfections of being human forgetting a name in the middle of a joke, rescheduling an appointment, switching pharmacies to save money and stacking them like evidence in a case.

“Mrs. Rodriguez and I joke about forgetting names,” I said. “I rescheduled an appointment because I had the flu. And I switched pharmacies because the new one has better prices. Would you like proof of all that, or are we done here?”

Jennifer’s voice rose. “You’re being impossible. We’re trying to protect you from yourself.”

“No,” I said, and my voice didn’t shake. “You’re trying to steal my home.”

Derek’s expression darkened. He leaned closer, lowering his voice the way men do when they think intimidation is more effective in private.

“You have no idea what we can do,” he said. “We have resources. We have lawyers. We can make your life very, very difficult.”

I met his eyes.

“Is that a threat?” I asked.

“It’s a promise,” he said.

Jennifer crossed her arms. “We’re filing for conservatorship this week. We have medical experts. We have documentation. We’ll prove you’re incompetent, and when we do, every decision you’ve made including that stunt with Tom will be reversed.”

I could feel my pulse in my throat, but my mind was steady.

“File whatever you want,” I said. “You’ll do it without my cooperation. Now get off my porch.”

Levenson lifted a hand slightly, as if he wanted to smooth things over, but he didn’t challenge Jennifer. He was there for a reason, and the reason wasn’t my wellbeing.

Derek took Jennifer’s elbow, and they turned away. Dr. Whitmore hesitated, eyes flicking to me with something like discomfort, then she followed. Levenson closed his briefcase and walked down my steps like he’d done it a thousand times.

I shut the door and locked it, then locked the deadbolt, then stood there with my hand still on the metal as if the extra pressure could keep the world out.

My hands shook after they left. Not because I doubted myself, but because the ugliness of it had finally surfaced without disguise.

My own daughter.

Building a case against me.

Like I was a stranger whose life could be filed into a folder and carried into court.

Margaret called later that evening, and her tone told me the escalation had already begun.

“They filed the petition,” she said. “Limited conservatorship.”

My throat tightened. “Already?”

“Yes,” she replied. “They attached a declaration from that psychiatrist. It claims you display signs consistent with early cognitive decline. They included statements from acquaintances. They’re painting a picture.”

“I’m not declining,” I said, and it came out as both anger and grief.

“I know,” Margaret said. “We’re going to fight it. We have Dr. Morrison’s evaluation. We have your records. We’ll bring witnesses. But Helen, I need you to be prepared.”

“For what?” I asked, though part of me already knew.

“Conservatorship hearings can be unpredictable. Judges err on the side of caution. Sometimes they think they’re protecting someone, and they don’t realize they’re handing power to the wrong person.”

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I walked through my house as if I were saying goodbye, even though I refused to accept that possibility. I touched the back of Robert’s chair. I ran my fingers along the edge of the bookshelf he’d built, the one that had survived three different paint colors and countless arguments about whether it needed to be replaced.

I stopped in the hallway and looked at a framed picture of Jennifer at five years old, missing a front tooth, holding a Popsicle that had melted onto her fingers. I stared at it longer than I should have. The child in the picture had my eyes. The adult who threatened me had my face. That was the cruelest part recognizing pieces of yourself in someone who could be so cold.

Around three in the morning, I sat on the bedroom floor and let myself cry, quietly, into the sleeve of my robe. The tears weren’t just fear. They were grief for something deeper than the house. Grief for the idea that the person you raised would protect you the way you protected her.

In the morning, I got up anyway.

I showered. I dressed. I made coffee and toast. I ate breakfast while reading the newspaper because I refused to act like a woman losing her mind. I was seventy-eight years old. I had survived losses that would have shattered other people. I was not going to collapse because my daughter found a lawyer.

Margaret scheduled an emergency hearing date, and then she did something that steadied me more than she probably realized.

“Helen,” she said, “I want you to rest for a few days. Not because you’re weak. Because you need to be sharp. You need to be calm. You need to show them exactly who you are, without exhaustion clouding it.”

I took her advice, even though resting felt like surrender.

For three days, I stepped back from the fight in small ways. I worked in my garden. I pruned the roses Robert and I planted thirty years ago. The thorn scratches on my fingers were grounding, reminders that I still lived in a real body in a real home. I had lunch with Susan at a little diner where the waitress called us “ladies” in that old-fashioned way and refilled our coffee before we asked.

Susan listened to the story with her mouth set in a hard line.

“That girl,” she said, shaking her head. “I always knew she had a mean streak. But this? This is something else.”

“I don’t want to hate her,” I admitted.

Susan’s eyes softened. “You don’t have to hate her. But you do have to stop excusing her.”

That sentence sat in my chest like a truth I’d been avoiding.

Tom called every day. He wanted to fly back immediately. He wanted to confront Jennifer. He wanted to fix this the way young men want to fix things with force, with certainty, with the belief that if you just say the right words loudly enough, the world will behave.

“Not yet,” I told him. “Save your strength. I’ll need you at the hearing.”

By Thursday, I felt clearer. Less raw. More dangerous, in the quiet way.

Friday afternoon, the doorbell rang again.

I checked the peephole and saw Jennifer standing alone this time, holding a bakery box.

For a second, my heart did something stupid. It lifted. It remembered old versions of her. It wanted to believe.

Then my mind caught up.

I opened the door but kept the screen latched.

“Mom,” she said, and her voice was softer, almost pleading. “Can we talk? Please.”

She held up the box. “I brought your favorite lemon bars from Rosie’s.”

The ones Robert used to bring me on Fridays.

That detail hit me hard, because it meant she still knew the map to my tenderness. It meant she could still walk straight to the places in my heart that hadn’t healed.

I hesitated, then unlatched the screen.

“Five minutes,” I said.

We sat at the kitchen table. Jennifer opened the box, and the smell of lemon and sugar filled the room. For a moment, I was back thirty years, watching her lick frosting off her finger, laughing when she got powdered sugar on her nose. That memory almost undid me.

“Mom,” she said, and her eyes glistened, “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry about all of this.”

She took a shaky breath. “I’ve been under so much pressure. Derek’s business hasn’t been doing well. We made bad investments. I panicked. I thought if we could sell the house, we could get back on our feet.”

There it was. The truth, or at least the part of it she was willing to admit.

“So you tried to take my home,” I said quietly.

Her mouth tightened. “I know how it sounds.”

“It sounds exactly like what it is,” I said.

“But Mom,” she said quickly, “I’m your daughter. I love you. This got out of control.”

She reached across the table for my hand. Her fingers were warm. Familiar. My body reacted before my mind did. My hand didn’t pull away fast enough.

“Can’t we just forget this?” she asked. “You withdraw the deed transfer. I withdraw the conservatorship petition. We start over. Family shouldn’t fight like this.”

I looked at her hand over mine and felt the weight of history birthdays, scraped knees, the first time she broke her heart and I held her while she cried. That was the trap of being a mother. Your heart keeps showing up even when it’s been wounded.

“And the house?” I asked.

“You keep it,” she said. “Of course. We’ll figure out our financial problems another way. I just want my mom back.”

It was a good performance. If I didn’t know her so well, I might have believed it.

“What about Derek?” I asked.

She waved a hand. “He agrees. He feels terrible. He just gets protective of me.”

I picked up a lemon bar and took a bite. It tasted exactly the way Robert used to bring it home. Sweet, tart, nostalgic. The kind of taste that can make you forgive things you shouldn’t.

“Jennifer,” I said, swallowing slowly, “do you remember what your father used to say about deals that sound too good to be true?”

Her eyes flickered. “What?”

“He’d say, ‘They usually are.’”

I set the lemon bar down. “You want me to give up the legal protection I put in place and trust that you’ll walk away. Trust that you won’t refile the petition the moment the house is back in my name. Trust that this is reconciliation and not another strategy.”

Her smile faltered. She opened her mouth, then closed it.

I leaned back slightly, keeping my voice calm. “I’m not doing it.”

Her expression changed so quickly it almost startled me. The softness drained. The eyes hardened. For a moment, I saw calculation.

“So that’s it,” she said. “No.”

“No,” I repeated.

She stood abruptly, the chair scraping the floor. “You’re making a huge mistake. We’re being nice now, offering you a way out. But when that hearing comes, we’re going to destroy you. We’ll prove you’re senile. We’ll prove Tom manipulated you. And then we’ll take everything anyway.”

“Then I’ll see you at the hearing,” I said.

She grabbed the bakery box like she regretted spending the money and stormed out.

I sat at the table long after she left, staring at the empty spot where the box had been, as if I could still smell the lemon.

Part of me wanted to chase her down the driveway and beg her to stop, not for my sake but for hers, because this kind of cruelty scars the person who commits it too. Another part of me wanted to slam my fist into the table until my knuckles bled.

Mostly, I felt something colder settle in.

Robert’s voice echoed in my head like it had so many times in our marriage when I was about to make an excuse for someone who didn’t deserve it.

Trust actions, not words.

Jennifer’s actions were clear.

That evening, Tom called. His voice was tight with anger.

“She came by?” he asked.

“She did,” I said.

“What did she say?”

I told him.

There was a silence on the line that felt like contained rage.

“I’m flying out,” Tom said.

“Not yet,” I told him. “I need you steady. I need you present at the hearing, not exhausted from picking fights you can’t win.”

“Grandma,” he said, and his voice cracked slightly, “I hate that she’s doing this to you.”

“I know,” I replied, and I meant it. “But we’re going to handle it the right way.”

After I hung up, I realized something I hadn’t fully accepted before.

I needed more than Tom.

I needed a community.

People outside the bloodline. People whose witness couldn’t be dismissed as “family conflict.” People who could speak to who I was in the daily world how I lived, what I did, how I functioned without anyone managing me.

I started making calls.

First, Susan.

Then Pastor Williams from church, a man who’d watched me organize food drives and coordinate volunteers without losing a detail.

Then Carol from my book club, who’d heard me argue about literature with more clarity than most college professors.

Then Mike from the library, who knew how often I showed up, how reliable I was, how many times I helped someone fill out a form online when they were too embarrassed to admit they didn’t know how.

One by one, they said yes.

Not out of pity. Out of anger on my behalf. Out of loyalty earned over decades of being the kind of person who shows up for others.

By Sunday, I had eight people willing to testify.

Margaret was impressed when I told her.

“This is exactly what we need,” she said. “A judge doesn’t just want family opinions. They want a picture. Your community provides that.”

The hearing date was set for Wednesday.

Ten days away.

Jennifer and Derek kept their distance for a while after her failed bakery performance. I knew they were preparing. I knew they were hunting for more “evidence,” more witnesses, more angles. Derek’s threat echoed in my mind sometimes in the quiet hours.

We can make your life very, very difficult.

But difficulty wasn’t the same as defeat.

Three days before the hearing, on Sunday evening, they came back.

Both of them this time.

And they brought flowers.

Expensive roses, the kind Robert used to buy me on our anniversary, deep red, wrapped in crisp paper like a gift from someone who wanted to be seen doing the right thing.

Jennifer held them out like a peace offering. Derek stood beside her with his solemn face, the kind men wear when they want to look sincere without doing the work of sincerity.

“Mom,” Jennifer said, voice carefully modulated, “please, can we come in? We need to talk. Really talk. Before this hearing destroys our family forever.”

Derek nodded. “Helen, we’ve done a lot of soul-searching.”

Against my better judgment or maybe because I needed to hear what they were planning I let them in.

We sat in the living room. Jennifer placed the roses on the coffee table between us like a treaty.

“Mom,” she began, “I’ve been seeing a therapist.”

I watched her closely.

She continued, “Working through my issues. I realized a lot of this comes from fear of losing you. When Dad died, I couldn’t handle it. And the thought of losing you too… I think I tried to control the situation in all the wrong ways.”

It was a good script. Therapy. Grief. Fear. All the right emotional buttons.

Derek leaned forward. “Jennifer’s been so stressed, Helen. We both have. We let stress turn us into people we’re not.”

“This conservatorship petition,” Jennifer said quickly, “it was wrong. We see that now.”

“So withdraw it,” I said simply.

“We will,” she said, too fast. “Tomorrow. First thing.”

Then she paused, and I felt it before she said it. The catch.

“But there’s just one thing we need to discuss first.”

Derek took over smoothly.

“The house,” he said. “We understand you wanting to protect it. We do. But transferring it to Tom… that hurt. Tom is young. He has his own life in Oregon. He doesn’t need this responsibility. And legally, it creates complications.”

“What kind of complications?” I asked, though my stomach already knew.

Jennifer reached for my hand again. She always did that when she wanted leverage, as if physical contact could override logic.

“Tom doesn’t really want the house, Mom,” she said. “We talked to him.”

My voice sharpened. “You talked to Tom?”

A flicker crossed Derek’s face irritation that I’d caught the lie.

“We tried to reach him,” Jennifer corrected quickly. “But the point is, a young man like that doesn’t want to be tied to property taxes and maintenance. It’s a burden.”

Derek nodded as if he’d just delivered common sense.

“So here’s what we propose,” he said. “You transfer the house back to your name. You maintain full control. And we sign a legal agreement drafted by a neutral attorney not ours stating we’ll never pursue conservatorship or claim the property. You keep your house. We get peace of mind. Our family heals. Everyone wins.”

I studied them. Jennifer’s earnest expression. Derek’s practiced sincerity.

“And if I say no?” I asked.

The room seemed to cool.

Jennifer’s fingers tightened around mine. “Mom, we’re trying to be reasonable. We’re offering you a solution that protects everyone, but if you refuse…”

She paused, and when she continued, her voice had an edge.

“We have more evidence than you realize. Did you know your credit card company flagged unusual purchases last month? Inconsistent with your normal pattern? That could indicate confusion. Poor judgment.”

“I bought Tom’s plane ticket,” I said. “That’s the unusual purchase.”

Derek jumped in immediately. “Or it could be seen as you making large financial decisions under outside influence. Tom’s influence.”

So that was the new angle.

Paint Tom as the manipulator.

Jennifer’s mask slipped. Her voice hardened. “We have testimony from a financial adviser who will say gifting property while facing family pressure to enter care is a red flag. We have neighbors who will testify you’ve seemed agitated. Paranoid. We have everything we need to win, Mom. Everything.”

“Then why are you here?” I asked calmly.

Because they weren’t here to reconcile. They were here to frighten me into surrender.

Jennifer stood abruptly, her composure cracking. “Because I’m still hoping you’ll see reason. Why are you being so stubborn? Why can’t you just trust me? I’m your daughter.”

“You’re trying to steal my house,” I said. “That’s not trust. That’s theft.”

Derek stood too, his face reddening. “You ungrateful We’re trying to help you and you’re treating us like criminals.”

“You threatened me in my own home,” I said, voice level. “You filed legal action to have me declared incompetent. You manufactured evidence. You’re trying to manipulate me right now. What exactly should I be grateful for?”

Jennifer grabbed the roses from the table and the petals shook loose, falling like small red bruises onto the carpet.

“Fine,” she snapped. “You want to do this the hard way? Wednesday’s hearing will be a nightmare for you, Mother. We’re going to dismantle everything you say. We’re going to prove you’re not fit to make decisions. We’re going to prove Tom coerced you.”

“Good luck,” I said.

Derek pointed at me, his voice low and ugly. “You have no idea what you’re up against. We have resources you can’t imagine. By the time we’re done, you’ll be lucky if they let you keep your own checkbook.”

They stormed out, leaving the roses scattered across my coffee table like evidence of their failed performance.

I sat very still and listened to their car peel out of the driveway.

My hands shook again, but not with fear.

With resolve.

No more doubts. No more second-guessing.

They’d shown me exactly who they were.

And on Wednesday, in front of a judge, I would show them exactly who I was.

Wednesday morning arrived cold and bright, the kind of winter morning that makes everything look sharper than it is. I woke before my alarm, lay still for a moment, and listened to the quiet of my house like I was taking inventory of what mattered. The furnace clicked on. The hallway clock kept ticking with stubborn patience. Somewhere outside, a trash truck rumbled down the street, and for a second the normalcy of it all made me want to laugh.

Then I remembered why I was awake.

I got out of bed and moved deliberately, not because I wasn’t afraid, but because fear didn’t get to steer. I showered. I dried my hair. I put on lotion the way I always did, smoothing it into my hands and arms like an ordinary woman preparing for an ordinary day. But nothing about this day was ordinary. This day was a performance, whether I wanted it or not, and the audience mattered.

I chose a navy suit because Margaret said navy reads as composed and reliable. Robert used to tell me it made me look “distinguished,” which was his way of saying I looked like a woman people shouldn’t underestimate. I pinned my hair neatly, not too severe, not too soft. I put on pearls because they were simple and familiar and because Jennifer always associated them with “Mom being serious,” which meant she’d recognize I wasn’t coming to beg.

Before I left my bedroom, I paused beside Robert’s dresser and touched the edge of it, just a brief brush of my fingertips against the wood.

If you’re here, I thought, then steady me.

In the kitchen, I drank half a cup of coffee and couldn’t taste it. My stomach felt hollow, but not with weakness. With readiness. I packed a folder with documents Margaret told me to bring, even though she had copies of everything, because there was something grounding about holding proof in my own hands. Dr. Morrison’s evaluation. Copies of my journal entries. The deed transfer and life estate paperwork. A list of community witnesses with their phone numbers and addresses. Even the smallest of these papers felt like armor.

Tom arrived just before eight, his rental car pulling into the driveway. When he stepped out, he looked tired, but he smiled anyway, the kind of smile people put on when they don’t want you to see how hard they’re holding themselves together.

“You ready, Grandma?” he asked.

“As I’ll ever be,” I said, and the truth was, I was more ready than I’d ever been for anything. Not because I wanted this fight, but because I’d stopped pretending I could avoid it.

We drove to the county courthouse together. The building sat in the middle of town like a monument to permanence, all stone steps and tall windows. An American flag snapped in the wind out front, and a smaller state flag hung beside it, both of them moving like they were trying to remind everyone who walked in that this place belonged to something larger than personal drama. The parking lot was already filling with people lawyers in suits, families in tense clusters, individuals standing alone with folders like mine.

Inside, we went through security. A metal detector. A deputy with a tired face and a polite tone. The smell of old paper and industrial cleaning solution. The fluorescent lighting that made everyone look a little paler than they probably were. The hallways echoed with footsteps and murmured conversations, as if the building itself was full of withheld emotion.

Margaret met us near the courtroom doors. She looked calm, as always, but her eyes were sharp, scanning the hallway the way someone does when they’re measuring threats and exits at the same time.

“Good,” she said when she saw me. “You look exactly how you should.”

“How’s it look?” Tom asked quietly.

Margaret’s gaze flicked to him, then back to me. “It looks like they’re trying to overwhelm you. Which means we’re doing something right.”

Jennifer and Derek were already there, sitting on a bench across the hall with their attorney, Richard Kramer. Jennifer wore a pale sweater and a scarf, something soft and innocent, like she’d dressed herself as a worried daughter instead of an aggressor. Derek wore a dark suit and looked irritated by the delay, like the court was an inconvenience rather than the arena he’d chosen.

When Jennifer saw me, her eyes narrowed. There was no apology in her face, no flicker of shame. Only determination, sharpened by the belief that she deserved what she wanted.

Tom’s shoulders tensed beside me.

“Don’t look at them,” I murmured.

“I’m looking so I remember,” he replied, voice low.

The courtroom doors opened and we filed in. The room was smaller than people imagine when they think “courtroom.” No grand movie set. Just beige walls, wooden benches, and the elevated judge’s bench at the front. The air felt dry. The carpet muffled footsteps but couldn’t absorb the tension. People took seats with the quiet urgency of those who know their lives are about to be discussed like paperwork.

Judge Caroline Brisco entered and took her seat. She was in her fifties with sharp eyes and a face that didn’t waste expression. She looked like someone who had heard every version of “I’m doing this for their own good” and learned to listen for what was underneath.

“This is a petition for limited conservatorship,” she began, glancing down at her file, then up at the room. “Filed by Jennifer Patterson Hullbrook regarding her mother, Helen Patterson.”

Hearing my name out loud in that setting made something tighten inside me. It was strange how quickly the court reduced you to a subject line. Helen Patterson. Proposed conservatee. As if I were an object being processed.

Judge Brisco adjusted her glasses slightly. “Mr. Kramer, you may proceed.”

Richard Kramer stood with polished confidence. He had the look of a man who believed his own voice was a tool capable of shaping reality. He didn’t glance at me the way a person looks at someone they care about. He looked at me the way a person looks at a case.

“Your Honor,” he said, “this is a straightforward situation. Mrs. Patterson is a seventy-eight-year-old widow whose cognitive abilities are declining, making her vulnerable to exploitation and impulsive decision-making. The petitioner, her daughter, has acted out of legitimate concern for her mother’s welfare.”

Jennifer’s face did the right performance tight worry, damp eyes, the expression of a devoted daughter burdened by responsibility.

Kramer continued. He spoke about “memory lapses,” “confusion,” “uncharacteristic behavior.” He spoke about the deed transfer to Tom as if it were proof of impairment rather than a rational response to a threat.

“Most alarmingly,” he said, “Mrs. Patterson recently transferred her primary residence to her grandson under circumstances that suggest undue influence.”

I felt Tom’s anger beside me like heat.

Kramer called Dr. Patricia Whitmore first. She approached the stand with professional composure. She described herself as a geriatric psychiatrist, spoke about early signs of cognitive decline, used careful language that sounded scientific but wasn’t grounded in anything she’d actually measured.

“In my professional opinion,” she said, “Mrs. Patterson displayed signs consistent with early stage dementia. Her refusal to cooperate with an evaluation, her defensiveness, her apparent paranoia regarding her daughter’s intentions these are all concerning indicators.”

Margaret stood for cross-examination and her calm was sharper than any raised voice.

“Dr. Whitmore,” Margaret said, “did you conduct a formal psychiatric evaluation of Mrs. Patterson?”

“I attempted to,” Dr. Whitmore replied.

“Yes or no,” Margaret pressed. “Did you conduct a formal evaluation? A standardized cognitive assessment? A clinical interview with sufficient time and consent?”

“No,” Dr. Whitmore admitted.

“Did you review Mrs. Patterson’s medical records from her treating physician?”

Dr. Whitmore hesitated. “I was provided with information by the petitioner.”

“That is not what I asked,” Margaret said, voice steady. “Did you review official medical records from her physician?”

“No.”

“So your testimony is based on secondhand reports from a daughter seeking legal control of her mother’s assets,” Margaret said, and the sentence landed with quiet force.

Kramer objected. Judge Brisco held up a hand.

“Overruled,” she said. “The witness may answer.”

Dr. Whitmore’s posture tightened. “I based my opinion on the information I had.”

“And the information you had,” Margaret said, “was curated by a petitioner with a direct financial interest in the outcome of this case. Correct?”

Dr. Whitmore’s lips pressed together. “The petitioner expressed concern.”

Margaret didn’t smile. She didn’t need to. “Concern and evidence are not the same thing,” she said, and turned slightly to the judge. “No further questions.”

The air in the room shifted. It wasn’t victory yet, but it was a crack.

Next came the “witnesses.”

Mrs. Rodriguez testified that I had “forgotten her name” last month. She looked uncomfortable on the stand, like someone who hadn’t expected her casual conversation to be turned into a legal weapon.

Margaret questioned her gently, then with precision. “Mrs. Rodriguez,” she said, “isn’t it true you and Mrs. Patterson have joked for years about both of you forgetting names sometimes?”

Mrs. Rodriguez glanced toward Jennifer, then back at Margaret. “Yes,” she admitted. “We… we do tease each other.”

“And have you ever seen Mrs. Patterson confused about anything important?” Margaret asked.

“No,” Mrs. Rodriguez said. “Not like that.”

The hairdresser testified about a missed appointment. Margaret produced documentation showing I had the flu that week and had rescheduled. The pharmacist’s calls were explained by receipts and prescription pickup records showing a switch to a different location for cost reasons. Each “proof” of decline turned out to be a normal life detail twisted into suspicion.

Kramer’s case wasn’t collapsing in a dramatic crash. It was unraveling thread by thread, the way lies often do when exposed to light.

Then Kramer pivoted to his real target.

“Your Honor,” he said, “even if Mrs. Patterson appears capable in this moment, we must consider her vulnerability to undue influence. The deed transfer to Thomas Patterson was executed under questionable circumstances. Thomas Patterson stands to benefit financially from this transfer. He had motive and opportunity to manipulate his grandmother.”

Tom’s jaw clenched. His hands tightened on his knees.

“We call Thomas Patterson to the stand,” Kramer said.

Tom walked up and took the oath. Sitting there, he looked young, but he held himself like someone who refused to be intimidated.

Kramer approached him with that practiced courtroom pacing, circling slightly as if he could trap truth by walking around it.

“Mr. Patterson,” he began, “when did you learn about your grandmother’s house?”

“I’ve known about it my entire life,” Tom said. “I grew up visiting it.”

“When did you learn you would inherit it?”

Tom’s gaze didn’t waver. “When my grandmother called and told me she wanted to protect it from my mother’s attempt to take it.”

Kramer’s eyebrows lifted as if he’d caught something. “Take it? Your mother is concerned about your grandmother’s welfare.”

“My mother threatened her,” Tom said, and his voice sharpened. “She told her she’d take the house through the courts and sell it.”

Kramer tried to regain control. “Do you have evidence of that threat?”

“We have texts,” Tom said. “We have a journal. We have ”

“Texts you could have coached her to write,” Kramer said quickly.

“Objection,” Margaret called. “Argumentative.”

“Sustained,” Judge Brisco said, and her tone carried mild irritation. “Mr. Kramer, ask questions. Don’t editorialize.”

Kramer changed tack. “Mr. Patterson, isn’t it true you benefit financially from this property transfer?”

“Not the way you’re implying,” Tom said. “My grandmother retained a life estate. She lives there as long as she wants. I can’t sell it. I can’t profit from it. I can’t do anything with it until after she’s gone. And I hope that’s decades from now.”

His voice cracked slightly on the last line, not in weakness, but in honest emotion. The room heard it. The judge heard it. Even Jennifer’s face flickered, just for a second, like something inside her resisted being fully monstrous.

Kramer tried again. “You flew here specifically to execute this transfer, correct?”

“I flew here because my grandmother called me and said she was being threatened,” Tom replied. “I flew here because someone had to show up for her.”

“And you didn’t advise her to transfer the property?”

“No,” Tom said. “She decided. She called an attorney. She took medical evaluations. She documented everything. She moved with more clarity than most people I know.”

Kramer stepped back like he was regrouping, then threw his last line.

“Mr. Patterson, would you agree that inheriting a home valued at ”

“Objection,” Margaret said. “Relevance. The value is speculative and not the issue.”

Judge Brisco nodded. “Sustained.”

Kramer’s jaw tightened.

Margaret’s turn came, and she moved through it like a person laying bricks.

She called Dr. Morrison, who testified with measured authority. He presented my physical and cognitive evaluation, described my scores, my mental acuity, my health.

“In my professional opinion,” Dr. Morrison said, “Mrs. Patterson is fully competent. Her memory, reasoning, judgment are intact. She is not suffering from dementia. There is no evidence of cognitive decline consistent with the claims presented here.”

Kramer tried to challenge him, but Dr. Morrison didn’t flinch. He spoke like someone who disliked his profession being used as a pawn.

Margaret called Susan, who testified about our neighborhood watch meetings, how I organized schedules and reported concerns, how I remembered details and helped people troubleshoot. She called Carol from book club, who testified about the complexity of the novels we discussed, about how I led debates and remembered themes and quotes. She called Pastor Williams, who testified about my volunteer coordination, my reliability, my ability to manage people and tasks without confusion.

Witness after witness painted the same picture: not of an elderly woman slipping into helplessness, but of a woman living a full, organized, competent life.

Then Margaret called me to the stand.

I stood and walked up calmly. My heart pounded, but my body moved with practiced steadiness. I took the oath. I sat down. I looked at Margaret and waited.

She asked me straightforward questions. My name. My age. My daily routines. How I handled finances. Whether I drove. Whether I managed my own medication. Whether I understood the deed transfer.

“Yes,” I said. “Yes. Yes.”

Margaret guided me toward the heart of it. “Mrs. Patterson, why did you transfer your home to your grandson?”

I didn’t rush. I didn’t dramatize.

“Because I was threatened,” I said. “Because my daughter told me she planned to take my house through the courts and sell it. And because I wanted to make sure she couldn’t.”

I felt Jennifer’s stare like a burn. I kept my eyes on the judge.

Margaret continued. “Did you make this decision voluntarily?”

“Yes.”

“Did Thomas Patterson pressure you into it?”

“No.”

“Did you consult an attorney?”

“Yes.”

“Did you obtain medical evaluations?”

“Yes.”

Margaret let each “yes” land like a stone in a wall.

Then Kramer stood for cross-examination.

He approached with a slight smile that tried to read as sympathetic. “Mrs. Patterson,” he said, “don’t you think it’s unusual for a woman your age to suddenly transfer her most valuable asset?”

“No,” I said. “I think it’s prudent, given the circumstances.”

“Circumstances,” he repeated. “You mean your daughter’s concern for your wellbeing?”

I looked at him steadily. “I mean my daughter’s threat.”

He tried to reframe. “Your daughter is trying to protect you.”

“She is trying to control me,” I replied, and my voice didn’t rise. “There is a difference.”

Kramer’s smile thinned. “You’re alleging your own daughter would harm you.”

“I’m stating facts,” I said. “She threatened legal action. She filed this petition. She brought strangers to my home to evaluate me without consent. Those are facts.”

Judge Brisco leaned forward slightly. “Mrs. Patterson,” she said, and the room quieted even more. “Why do you believe your daughter filed this petition?”

This was the question that mattered. Not what I felt. Not what I suspected. What I believed, and whether the court believed my belief had reason.

I met the judge’s eyes.

“Because she needs money,” I said, and my voice stayed steady. “Because Derek’s business is failing. Because they tried to get me to sign my house over and I refused. Because my house is valuable, and they see it as a solution to their problems. This isn’t about care. It’s about control.”

Jennifer’s breath hitched. She began to cry loud, dramatic sobs, the kind meant to soften an audience. Derek put his arm around her and held her like she was fragile.

Judge Brisco didn’t react. Her eyes stayed on me.

Kramer tried to regain momentum by pointing to Jennifer’s tears as proof of sincerity, but the judge’s expression didn’t change.

“Anything else, Mr. Kramer?” Judge Brisco asked after a moment.

Kramer looked down at his notes, then up, and the truth was written in his posture. He was out of road.

“No, Your Honor,” he said.

Judge Brisco closed the file folder with a decisive motion. “I will take this under advisement,” she said. “I will issue a ruling within forty-eight hours.”

The room exhaled. People stood. Papers shuffled. The bailiff called instructions. Jennifer glared at me as if my refusal to be stolen from was a betrayal. Derek whispered urgently to Kramer. Tom looked at me with fierce pride and something like heartbreak.

Outside the courthouse, the air felt colder, but cleaner. Tom offered to drive, and I let him, mostly because my hands were still buzzing from adrenaline.

“You did incredible,” he said once we were in the car.

“I told the truth,” I replied.

“That’s what I mean,” he said. “That’s what scares them.”

At home, I tried to keep my day normal. I made soup. I watered the plants. I folded laundry. But I couldn’t settle. Every time the phone buzzed, my body jolted. Every time a car passed outside, I looked up.

That night, I slept in short bursts. I dreamed of Robert’s chair being carried out of the house by strangers. I dreamed of Jennifer standing in my doorway holding a set of keys and smiling like she’d won. I woke up before dawn and sat at the kitchen table with a mug of tea and the house’s silence around me.

In the quiet, I thought about the word I’d used when I first described what Jennifer didn’t know. “Sold.”

It wasn’t sold on the open market. It wasn’t a “for sale” sign and strangers touring my home. But it was sold in the way that mattered. Signed away. Legally transferred. Removed from her reach. The deed had been recorded. The truth existed in the public record, not in her assumptions.

And now, the rest depended on whether the court could see what my daughter refused to admit: that competence isn’t just memory tests and doctor’s notes. Competence is the right to say no. The right to protect yourself. The right to refuse being packaged and handed over like property.

Thursday passed slowly. Every hour felt stretched. Susan dropped by with a casserole I didn’t need, which was her way of showing love without turning it into a conversation that might break me.

“You’re going to be fine,” she said, setting the dish on my counter.

“I don’t know that,” I said.

She looked at me with that steady neighbor wisdom. “I do.”

On Thursday afternoon, I was in the backyard pruning roses when my phone rang.

It was Margaret.

“Helen,” she said, and I heard it in her voice before she even said the words. The slight lift, the satisfaction of a battle won properly.

“The judge issued her ruling.”

My heart hammered. My fingers tightened around the phone.

“Complete dismissal,” Margaret said. “She denied the conservatorship petition in its entirety.”

For a second, I couldn’t breathe. The air seemed to stall in my lungs as if my body didn’t believe relief was allowed.

“She… dismissed it,” I whispered.

“Yes,” Margaret said. “And Helen, there’s more. Judge Brisco stated in her opinion that the petition was frivolous and brought in bad faith. She’s ordering Jennifer and Derek to pay your attorney’s fees.”

I sat down hard on the garden bench. “She’s ordering them to pay…”

“All of it,” Margaret said. “Every penny. And she’s flagging their attorney for potential sanctions for bringing a baseless case. Helen, this is a complete victory.”

I stared at the rose bushes in front of me. The thorns. The new buds. The tough, stubborn life of them. I felt something inside me loosen, like a tight knot finally untying after weeks of strain.

When I hung up, I didn’t cry right away. I just sat there, letting the sunlight hit my hands, letting the words settle into reality. Dismissed. Denied. Bad faith. Frivolous. The language of the court was cold, but in that moment it felt like protection.

Tom called minutes later. He was shouting with joy before I even finished saying hello.

“We won,” he said. “Grandma, we won.”

“You helped me win,” I replied.

“You won,” he insisted. “You stood up in that room and made them see you.”

That evening, Margaret emailed me the written opinion. I read it more than once, savoring each sentence the way you savor something you thought you might never taste again.

The judge’s words were clear. She found no credible evidence of diminished capacity. She noted my medical evaluation and the community testimony. She noted the weakness of the petitioner’s evidence and the timing how quickly Jennifer filed after the property transfer, how obvious the motive looked when held up to light.

I sat in Robert’s chair by the window and felt my house around me, solid and quiet. The sun set outside, and the room turned golden, then dim.

For the first time in months, I believed I might actually keep living my life without someone trying to seize it.

But I also knew something else.

Jennifer would not accept this quietly.

People like her rarely do.

They don’t see a court ruling as truth. They see it as an obstacle.

And obstacles, in Jennifer’s mind, were made to be pushed aside.

4/4

The next morning, I woke up and the first thing I felt was a strange, unfamiliar lightness, like someone had opened a window in a room I didn’t realize I’d been suffocating in. The house was still the same. The kitchen still smelled faintly of coffee grounds from yesterday. The hallway still held that soft dimness before sunrise. But my body was different. My shoulders weren’t pulled up toward my ears. My jaw wasn’t clenched.

For weeks, I’d been living as if a hand was hovering over my life, ready to snatch it away. Now that hand had been slapped back by the one institution Jennifer couldn’t manipulate with tears and guilt.

I made coffee and sat at the table with both hands wrapped around the mug. Outside, the neighborhood looked like it always did on a weekday morning. The streetlights flickered off one by one. A dog barked two houses down. Somewhere, a garage door rumbled open and a car backed out, headlights sweeping across frost on the pavement.

Normal life was still happening.

And I was still part of it.

Tom came over midmorning, carrying a paper bag from the local diner, the one with the cracked vinyl booths and the best pancakes in town. He slid it onto my counter and smiled in that boyish way that still made him look younger than twenty-five.

“Celebration breakfast,” he said.

“You know I could’ve cooked,” I teased, but I didn’t move to do it.

“I know,” he said. “But this is symbolic. Also, Susan told me you’ve been living on soup and stubbornness.”

Susan. Of course she’d reported on me. That was her way. She kept an eye on everyone like the neighborhood was a family and she was the unofficial aunt who didn’t tolerate nonsense.

Tom and I sat at the kitchen table and ate eggs and toast and the kind of potatoes that taste better because you didn’t have to make them. He talked about the hearing, replaying moments like he couldn’t believe how clearly the judge had seen through Jennifer’s act.

“I thought she’d buy it,” he admitted quietly at one point. “I thought the court would hear ‘elderly’ and decide ‘better safe than sorry.’”

“That’s what they were counting on,” I said.

Tom leaned forward. “Grandma, I’m proud of you.”

I looked down at my plate for a moment because pride, when it comes from someone you love, can make your throat tighten just as much as grief.

“Thank you,” I said.

After he left, I tried to do something I hadn’t done in a while.

I tried to relax.

It was harder than I expected. Fear doesn’t vanish the moment a judge makes a ruling. It lingers in the body. It teaches your muscles to stay ready. It makes your mind keep scanning for the next threat. Even with the petition denied, I couldn’t fully trust the peace. Jennifer had lived in my head for weeks like a storm cloud, and storm clouds don’t evaporate instantly just because you tell them to.

That afternoon, Margaret called again.

“Helen,” she said, “Jennifer’s attorney contacted me.”

My stomach tightened. “For what?”

“They want to discuss a settlement agreement.”

I blinked. “Settlement? They lost. What’s there to settle?”

Margaret’s voice stayed calm. “They’re worried about sanctions. Judge Brisco referred Kramer to the state bar for investigation, and that’s not something attorneys take lightly. They want you to agree not to pursue a separate elder abuse complaint or sue for damages. In exchange, they’ll sign a binding agreement: no future conservatorship petitions, no claims on your property, no interference.”

I stared out the kitchen window at the backyard, at the rose bushes that had survived winter after winter because their roots were deep.

“What do you recommend?” I asked.

“I recommend you take it,” Margaret said. “Not because you owe them mercy. Because you deserve closure. You can keep fighting, and you might win even more, but it will cost you time, stress, and energy. This agreement can lock the door.”

I didn’t answer immediately. Part of me wanted to burn everything down. Part of me wanted Jennifer to feel what she’d put me through, to be publicly shamed, to lose more than money. But another part of me, the part that had been holding its breath for weeks, wanted the fight to end.

“I want one additional clause,” I said.

Margaret chuckled softly. “Of course you do. What clause?”

“If they violate the agreement in any way,” I said, “any contact, any legal action, any attempt to interfere with my life, they forfeit any claim to my estate entirely. Everything goes to Tom. They get nothing.”

Margaret’s laughter was brief, warm. “I’ll make sure it’s crystal clear.”

When I hung up, I sat still for a long time. The idea of disinheriting my own daughter should have shattered me. It should have felt like cutting off my own arm. But what I felt was something calmer.

I had already been disinherited.

Not on paper, but in spirit. Jennifer had removed herself from the role of daughter when she tried to take my autonomy and call it love. The legal consequences were simply matching the truth that already existed.

The settlement agreement was finalized on Friday afternoon.

Jennifer and Derek signed it at their attorney’s office. I signed it at Margaret’s. We didn’t have to see each other.

The agreement was comprehensive and brutal in its clarity. No future conservatorship petitions under any circumstances. No contact with me unless I initiated it. No claims to my property, assets, or estate. No interference with my medical care or legal decisions. Payment of attorney’s fees within thirty days. Violation of any term resulted in complete disinheritance.

Margaret read it aloud once more, then looked at me. “Are you comfortable with this?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Are you sure?”

I thought about the way Jennifer’s voice sounded in my kitchen when she said, Start packing. I thought about Derek’s threat. I thought about strangers on my porch with clipboards and lies. I thought about lying awake at three a.m. on my bedroom floor, crying into my sleeve like a woman who’d lost her child while she was still alive.

“I’m sure,” I said.

After I signed, Margaret slid the papers into a folder and pressed her palms flat on the desk like she was sealing something.

“It’s done,” she said.

On Saturday morning, I woke up in my house, my home, knowing something I hadn’t known in months.

I was safe.

Not just emotionally, not just because I wanted to believe it, but legally.

Protected.

Untouchable.

I made coffee and sat in Robert’s chair, looking out at the garden we planted together forty years ago. The world outside was quiet, winter bare, but the bones of life were still there, waiting for spring.

Somewhere in town, Jennifer was probably crying or raging or blaming everyone but herself. Derek was probably calculating how to recoup their losses.

For the first time, I didn’t care what they were doing.

I cared about what I was doing.

My phone rang.

It was Tom.

“Hey, Grandma,” he said. “I was thinking. I get spring break in March. What if I come out for a week? We can finally tackle that garage organization you’ve been talking about.”

I smiled. “I’d love that.”

He hesitated, then said softly, “Thank you for trusting me with the house. I know it’s more than property. It’s you and Grandpa. I promise I’ll take care of it.”

“I know you will,” I said. “That’s why I did it.”

After we hung up, I walked through my home slowly, not like a guest packing to leave, but like a woman reclaiming her space. Every room held memory. Every corner held a story. The house had witnessed love and loss, joy and sorrow, births and funerals, arguments and forgiveness.

It would remain in the family.

Not the family that shared blood and used it as entitlement, but the family that showed up, that protected rather than exploited.

That evening, I treated myself to dinner at the Italian restaurant Robert and I used to love, the one downtown with white tablecloths and candles that flickered against brick walls. I ordered his favorite wine, raised the glass quietly, and toasted him.

“Still here,” I whispered, and the words tasted like triumph and grief mixed together.

Six months later, my life had changed in ways I didn’t expect.

The first change was Tom.

In August, he called me with excitement in his voice. “Grandma, you’re not going to believe this.”

“What?” I asked, already smiling.

“I got offered a teaching position,” he said, “at a high school forty minutes from you.”

I sat down hard on the couch. “Forty minutes?”