On the day the inheritance was divided, her father left his daughter nothing but a few withered potted plants, as if to say she wasn’t worth caring about. She quietly took them home, tended to them day after day, and turned that barren corner of the yard into a lush garden, then into a small farm and a steady, thriving livelihood that left everyone stunned. Years later, when everything had turned around, her brothers came looking for her, sincerely asking her to share the secret.

A young woman inherited nothing but withered, dried-out trees, while her brothers received the best pieces of land.

“With these dead chunks of wood, you’ll learn the value of effort,” her father said with open contempt.

No one expected that the trees everyone dismissed as useless were hiding a secret that could change her fate forever.

While her two older brothers, Andrés Javier and Mateo Raúl, had gone off to college in the city and only came home for holidays, she stayed behind like a loyal shadow, cooking, cleaning, and tending to every need of Don Ramón, a man hardened by sun and wind and made unyielding by life. Out here, in the sun-worn stretch of California’s Central Valley where summer could scorch the paint off a mailbox and drought was a word people said with the same tightness they used for foreclosure, land was not just land. It was identity. It was inheritance. It was power that moved quietly through families, like water through a pipe you couldn’t see until something cracked.

That April morning, Attorney Salazar’s probate office smelled like old paper, lemon polish, and the kind of air-conditioning that fought a losing battle against the heat seeping in from the parking lot. A framed photo of a river in flood season hung behind the receptionist’s desk, all green rush and promise, like a memory the building was trying to hold onto. Elena Mendoza sat in a corner chair with her hands clasped in her lap over her simple dark dress, the fabric soft from too many washings. Her nails were short, the kind that broke if you let them grow. She had spent so many years doing the work no one applauded that she had learned to move quietly, to take up less space without meaning to.

Across the room, her brothers sat in the central chairs facing the walnut desk, legs crossed, shoulders wide, looking like men who had never had to ask permission for anything. They wore clean boots and crisp shirts, the kind you put on when you expect to sign paperwork and come out winning.

Don Ramón had died three weeks earlier after a long illness, and today his will would be read.

Elena kept her eyes on the edge of the desk, on the neat stacks of folders, on the way the attorney’s pen rested perfectly parallel to the blotter. She told herself to breathe. She told herself not to hope for too much.

She wasn’t dreaming of luxury. She wasn’t picturing vacations or a shiny truck with leather seats. She was picturing a small place that was hers, a little margin of safety, something that said the years she spent cooking for him, lifting him when his joints failed, driving him to the clinic in town while her brothers were off living their real lives, had meant something.

Attorney Salazar adjusted his glasses and cleared his throat, the sound crisp as a page turning.

“I will now read Mr. Ramón Ignacio Mendoza’s final wishes,” he said, voice practiced, neutral, as if this were only a transaction and not the moment a family cracked open.

Elena felt her chest tighten anyway.

“To my eldest son, Andrés Javier Mendoza,” the attorney continued, “I leave the family house and the irrigated plots bordering the river, totaling twenty hectares.”

Andrés’s mouth lifted into a small smile, satisfied, almost bored. Those were the best pieces of land in the area, flat and rich, close enough to the irrigation district lines that you could keep trees alive even when the river ran low. Everyone in town knew those parcels. When people drove by, they nodded like they were looking at something permanent.

“To my second son, Mateo Raúl Mendoza,” Salazar read, “I leave ten hectares of olive grove and my mother’s house in the village, along with the tractor and farming tools.”

Mateo nodded, pleased, as if he’d been expecting it. Those olive trees produced premium oil that sold at farmers markets up and down the coast, little bottles with fancy labels that made tourists feel like they were buying something authentic.

Elena held her breath. Now it was her turn. She tried not to look eager, as if eagerness might be punished.

“And to my daughter,” the attorney said, “Elena Lucía Mendoza, I leave the upper plot and the fruit orchard.”

The silence that followed felt physical, like a weight placed gently but firmly on her shoulders.

Elena blinked, confused. The upper plot was the rocky piece of land up the hill, far from the river, where her father had once tried to plant fruit trees years ago and then abandoned the whole thing. An unfinished project no one had visited in a long time, the kind people pointed at and laughed about when they’d had one beer too many at the diner.

Andrés let out a quiet laugh that carried more meaning than sound.

“That’s all?” Elena asked, her voice thin, almost not her own.

Attorney Salazar looked at her over his glasses, and for the first time that morning his face softened, just a fraction.

“There is a separate note your father left specifically for you,” he said, and he slid a sealed envelope across the desk.

Elena took it with trembling fingers. The paper felt heavier than it should have, like it contained more than words. She broke the seal, unfolded the sheet, and saw her father’s uneven handwriting, the way it slanted when his patience ran out.

“ELENA,” it began, all caps, as if he needed to shout even from the grave.

“I’m leaving you those withered trees up on the hill. With those dead chunks of wood, you’ll learn the value of effort, something you never understood because you’ve spent your life hiding at home like a coward. Maybe now you’ll learn what real work is.”

Hot tears burned at the corners of her eyes, but she wouldn’t let them fall. Crying in front of her brothers felt like handing them a victory they didn’t even have to earn.

She folded the paper slowly and slid it back into the envelope as if the neatness could erase what it said. She stood, smoothing her dress.

Andrés leaned back in his chair and shrugged, like this was all normal.

“Guess you got your lesson,” he murmured.

Elena did not answer. She didn’t trust her voice. She walked out into the bright parking lot, the light so harsh it made everything look sharper, more honest. The air smelled like hot asphalt and cut grass from the little strip by the building, and somewhere a truck door slammed.

She got into her old sedan and sat with her hands on the steering wheel. For a long moment she didn’t start the engine. She stared at the glove box, at the small crack on the dashboard that had been there since last summer’s heat wave. Her father’s words kept echoing, not just in her ears, but in her body, as if her muscles remembered being dismissed.

Dead chunks of wood.

Coward.

Real work.

She drove home on roads she knew so well she could have taken them with her eyes closed, past orchards and fields, past the river that ran thin and brown this time of year, past the levee where boys still fished even when there was nothing to catch. The family house, now Andrés’s, sat behind a line of dusty trees, the porch sagging in one corner but still solid, still familiar.

She didn’t go inside. She couldn’t.

Instead she turned up the road that climbed toward the upper plot, the one people said was only good for goats and rattlesnakes. The pavement gave up after a few miles and became dirt, the kind that kicked up in pale clouds and coated everything with a film of the valley.

The gate at the entrance was rusted iron, the lock mottled with green and brown like it had been forgotten by time. The key Attorney Salazar had given her finally turned after a few tries. The sound was small, but it felt like a door in her life opening whether she wanted it or not.

She stepped through.

The land in front of her made her chest tighten. One hectare of rock-strewn ground, scrubby weeds, and old fruit trees standing like twisted skeletons. Apples, pears, plums, cherries, planted fifteen years earlier when her father had been briefly obsessed with the idea of “doing something up here,” before drought and stubbornness made him walk away. The trees looked dead, gray bark split and dry, bare branches stabbing at the pale spring sky like accusing fingers.

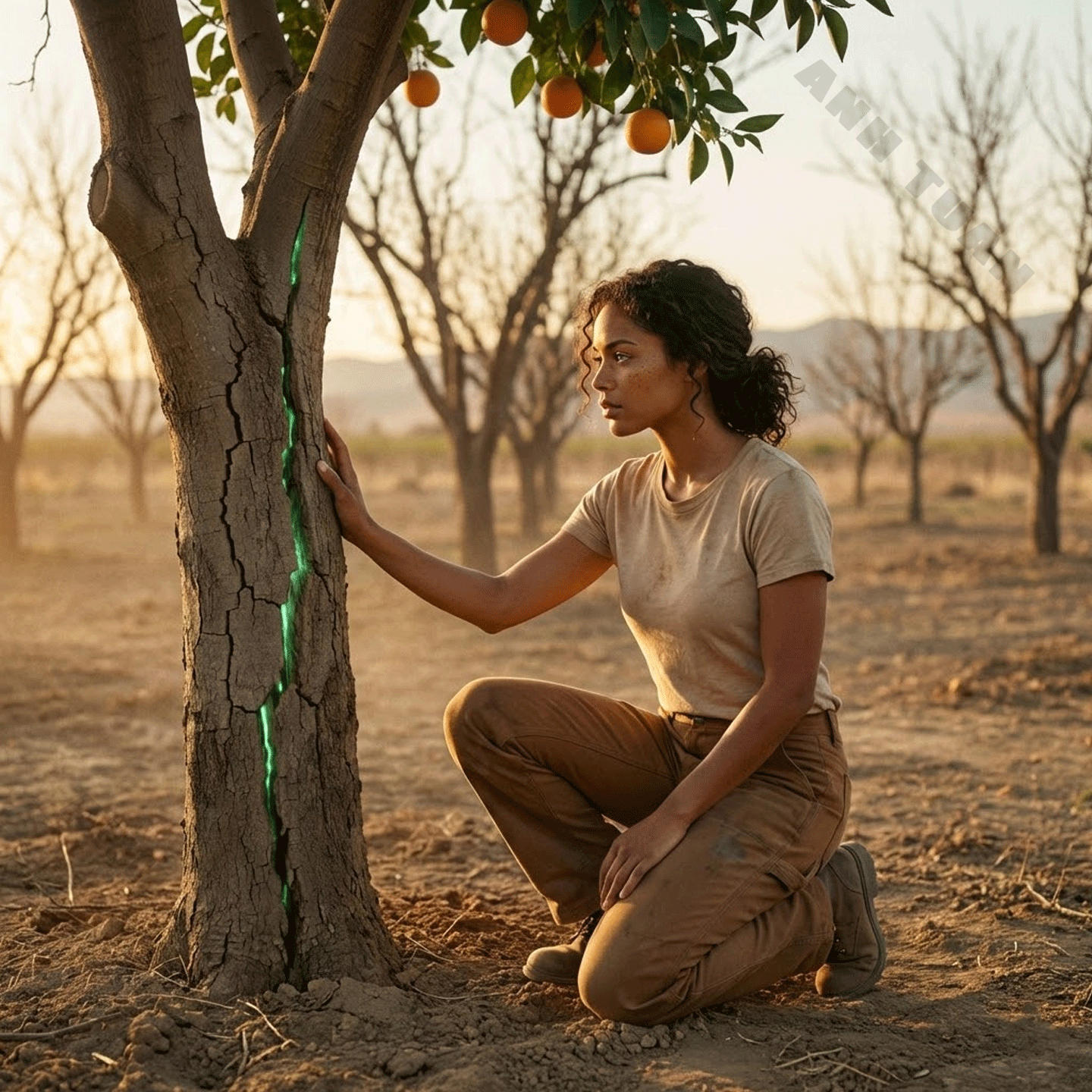

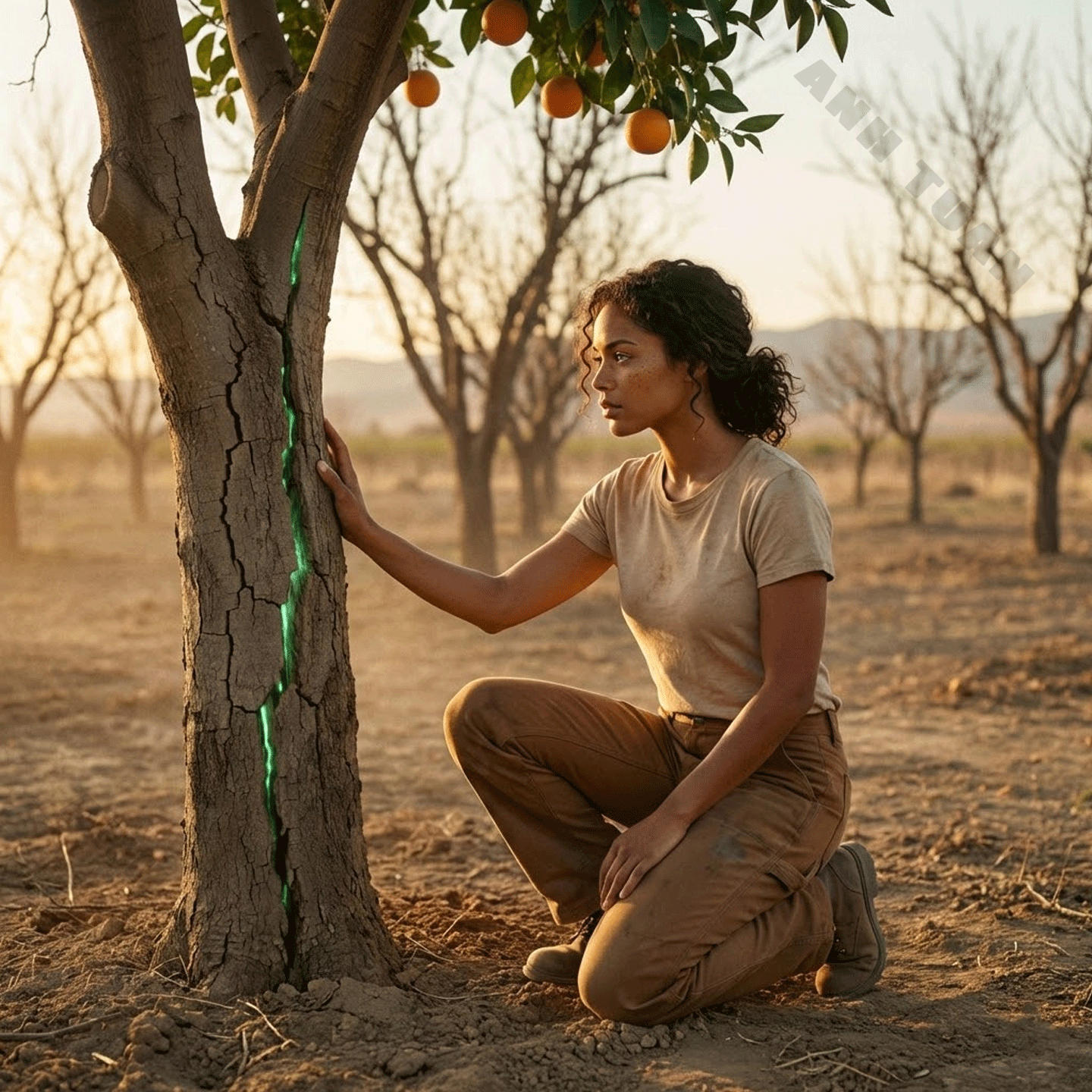

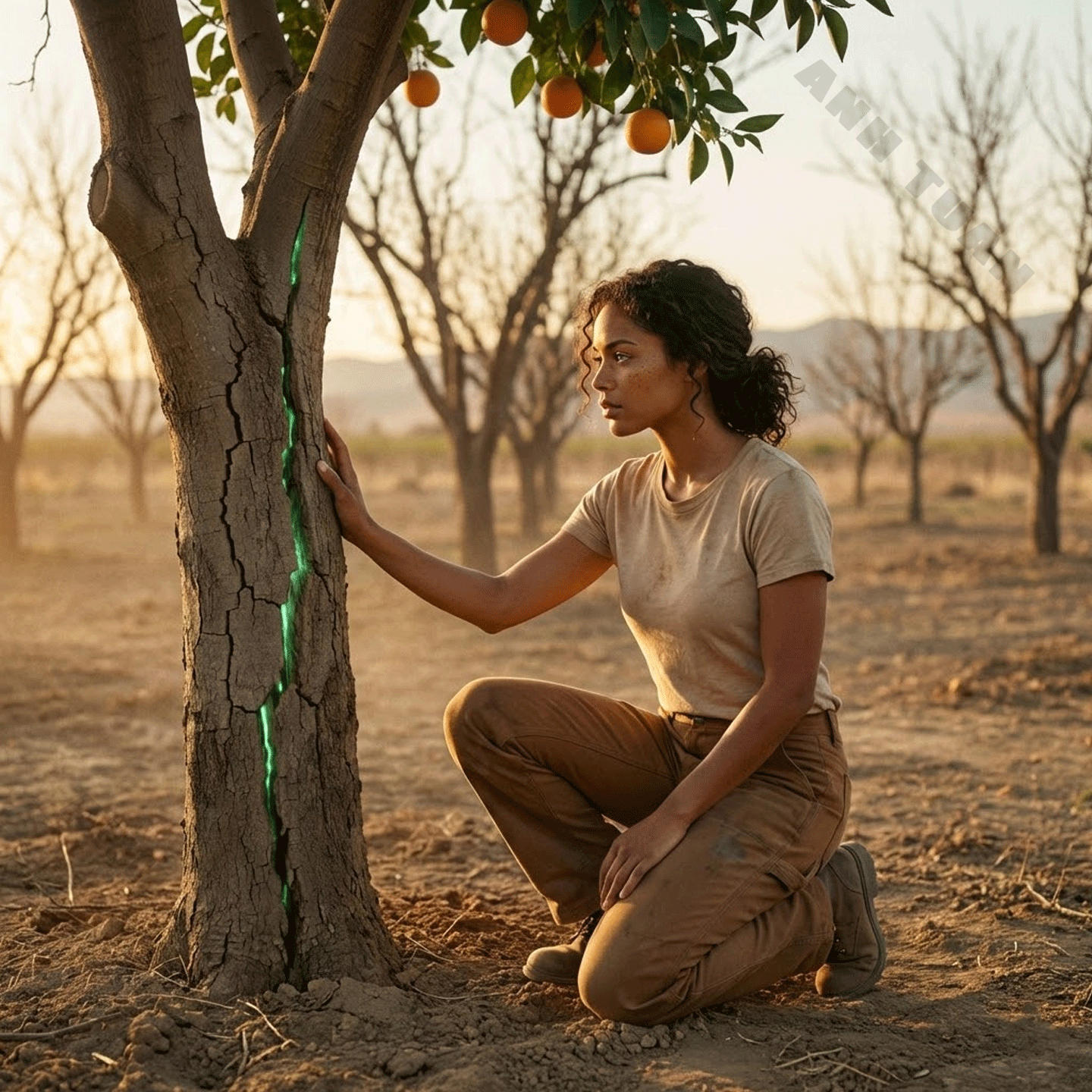

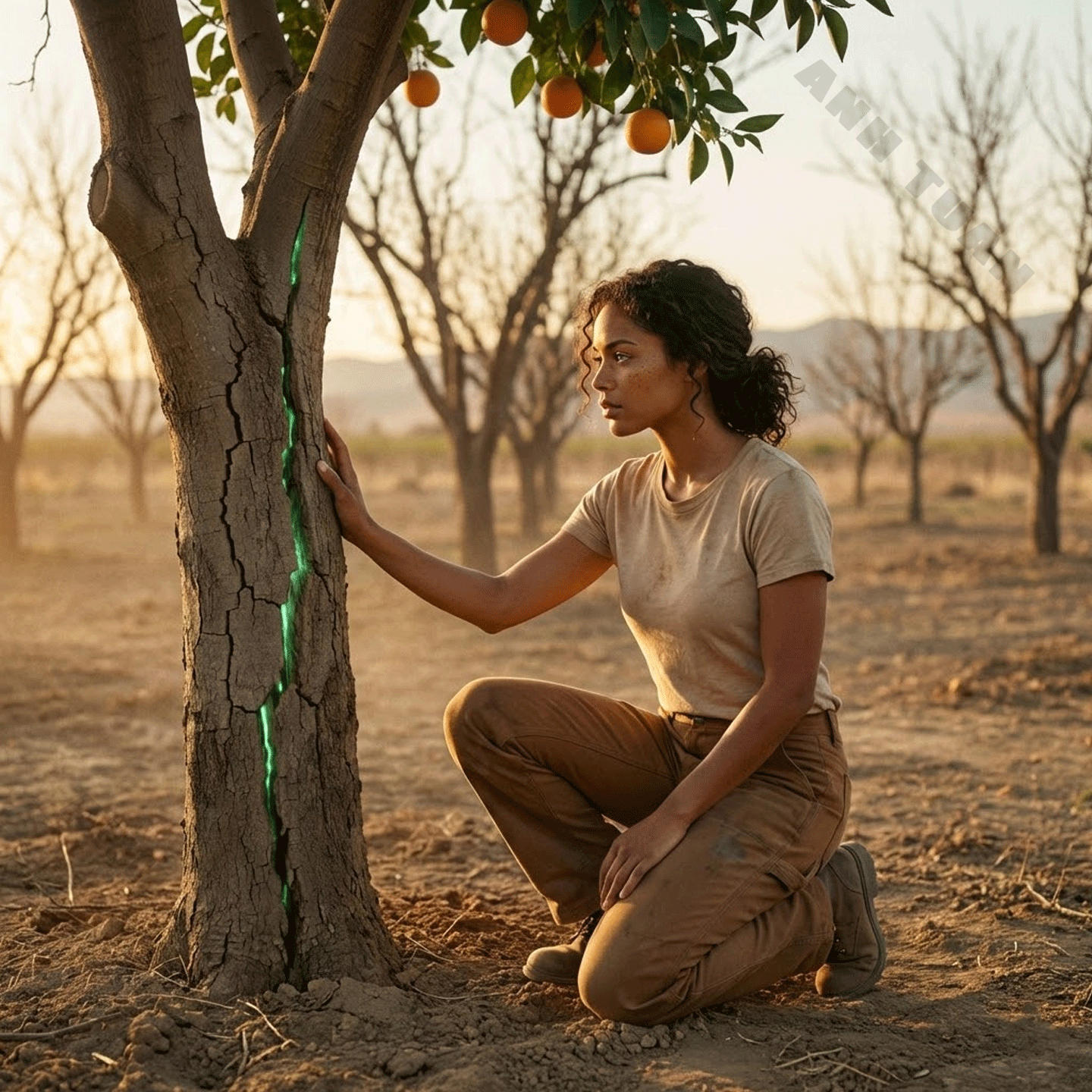

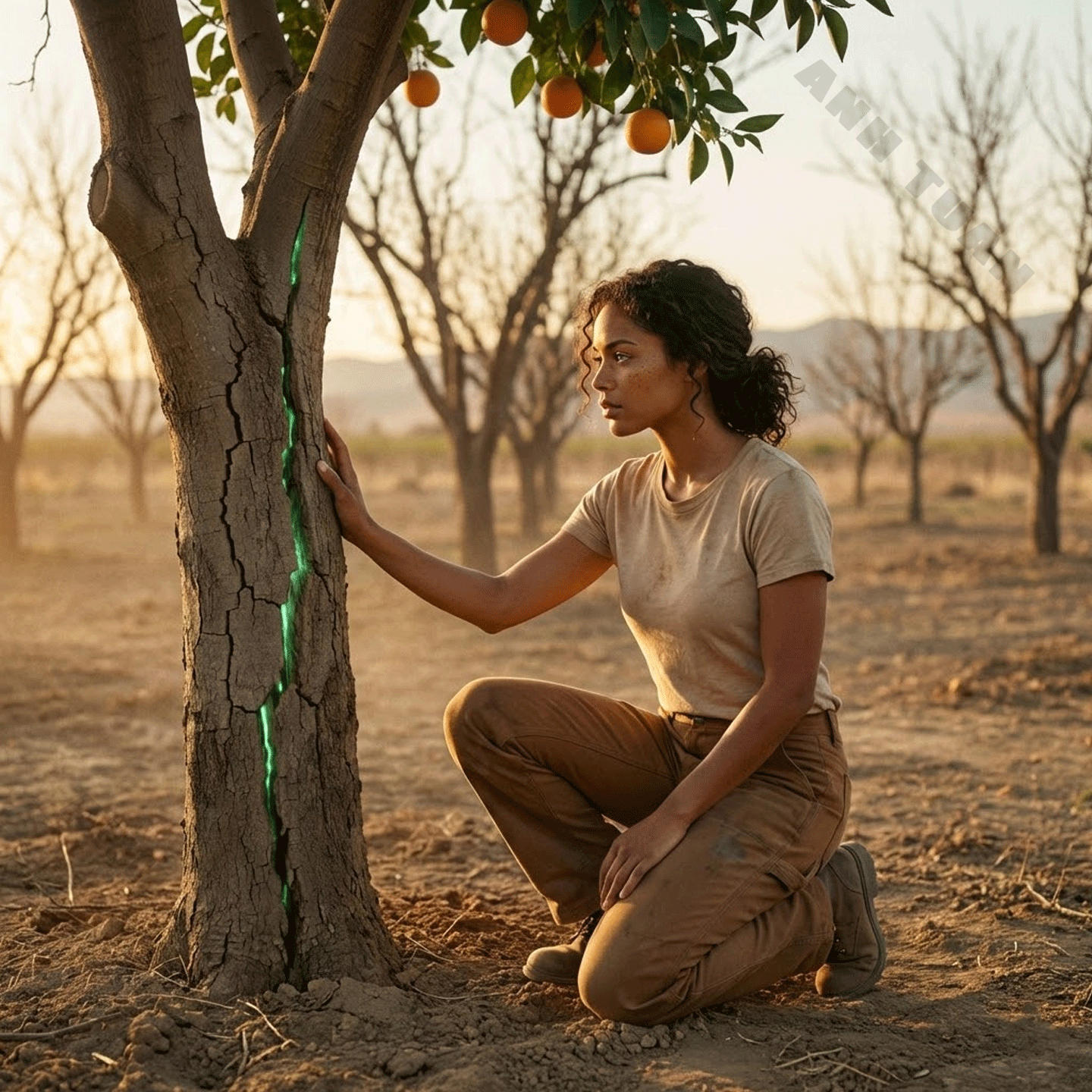

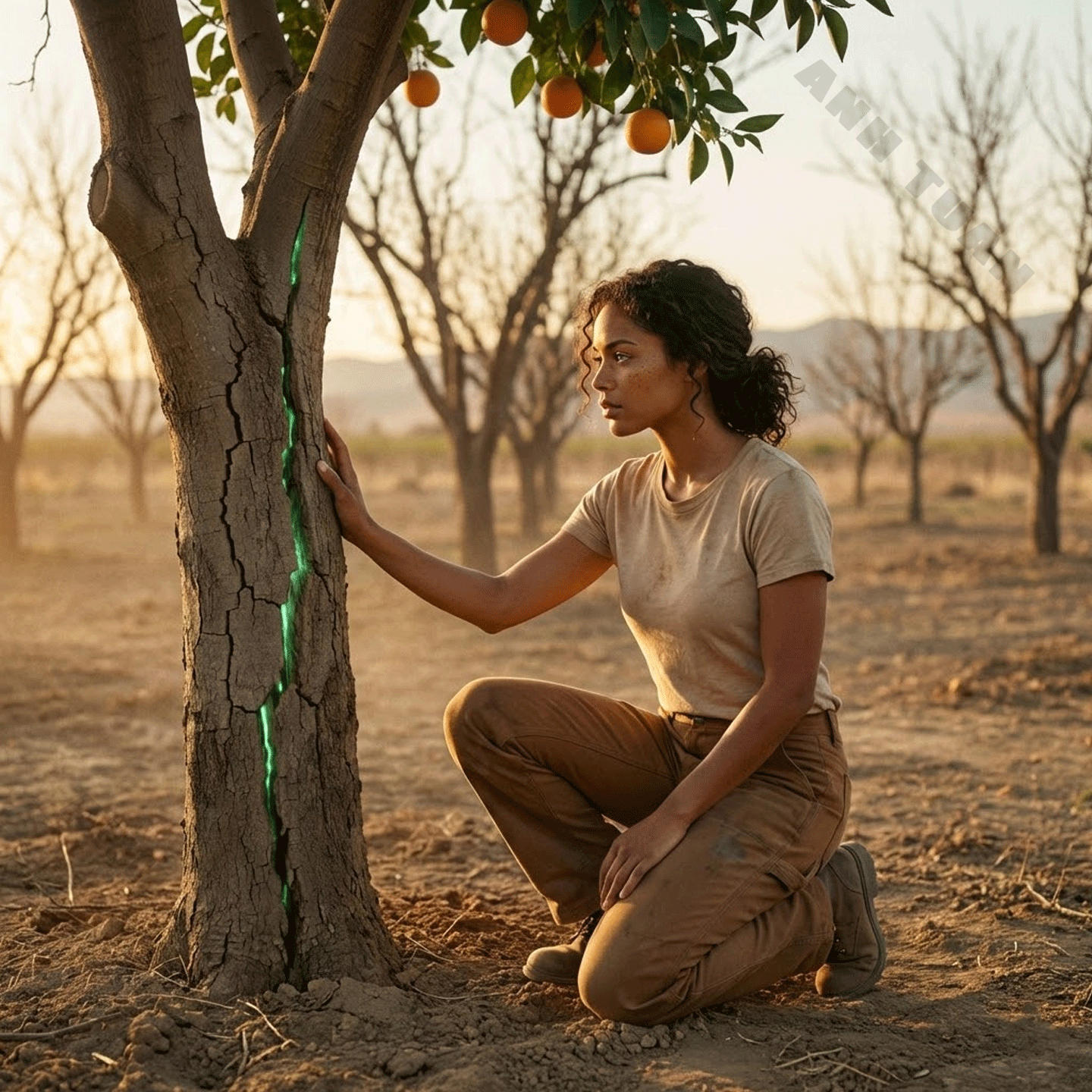

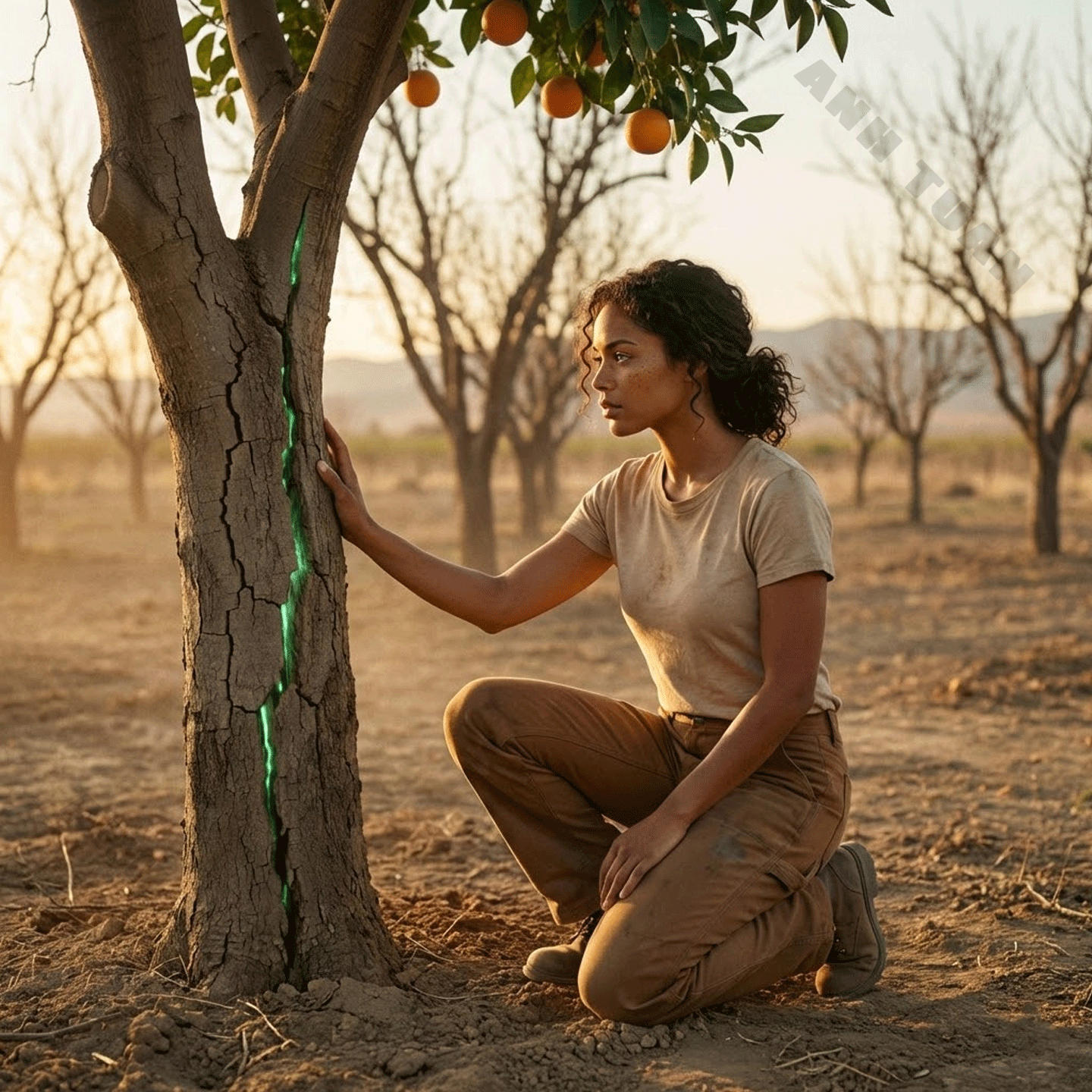

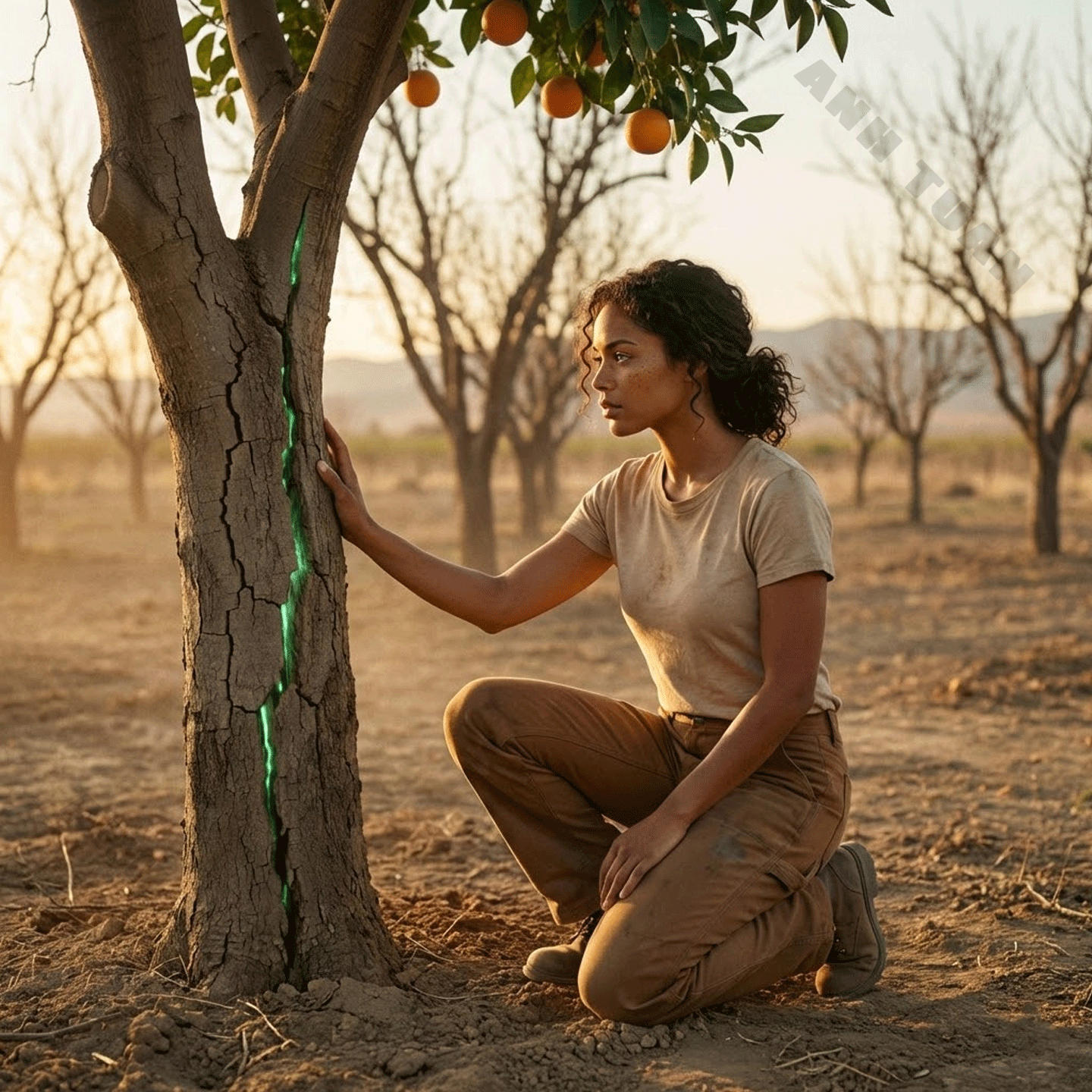

Elena walked up to the nearest one, an apple tree with a warped trunk. The bark was cracked. No leaves. No blossoms. No fruit. She touched the trunk and it felt rough and cold, like touching something that had already been mourned.

“Dead chunks of wood,” she muttered, and the words tasted bitter.

She sank down beneath the thin scrap of shade the tree could offer, more habit than comfort, and finally let the tears come. They came hot at first, then steadier. She cried for the injustice, for the years she’d lost, for the dreams she’d kept folded away like clean sheets she never got to use. She cried until her face felt numb and her throat hurt, until she had nothing left and the wind was the only thing moving.

When the sun began to drop, the light shifted and softened, turning the rocks gold instead of cruel. Elena stood slowly, wiping her cheeks with the back of her hand. She looked around with new eyes. This was hers, no matter how her father had meant it. She could sell it cheap and walk away, take whatever scraps she could get and disappear into a job in town that would never belong to her either.

Or she could do something else.

She stepped back to the apple tree and, almost on instinct, scratched the bark with her fingernail. The outer layer flaked away like ash. Beneath it, just under the gray dryness, she saw a faint streak of green.

She froze.

Her heart hammered hard enough she felt it in her throat. She pulled the small pocketknife from her jeans, the one she used for twine and stubborn packaging, and scraped a little more carefully.

Inside the tree, the wood was damp. Alive.

Elena’s breath caught. She pressed her fingertips to it as if touch could confirm what her eyes were telling her.

She ran to the next tree, scraping, checking, almost afraid she’d imagined it.

Green.

Another tree.

Green again.

She moved down the row, her hands shaking, her mind racing, each scrape like peeling back an insult to find a secret underneath. Out of twenty-two trees, most showed the same sign. Dead on the outside, but alive on the inside, like something that had been forced to shut down to survive.

“They’re not dead,” she whispered, and her voice sounded strange in the open air. “They’re just… sleeping.”

A sound behind her made her spin. For a split second, fear surged, the animal kind that lives in your spine.

At the entrance, an old man stood leaning on a cane, watching her. His hat brim shaded his eyes. His posture was bent, but there was something steady about him, like the hills themselves had taught him how to endure.

“Someone finally came to visit this abandoned orchard,” he said. His voice was rough, like gravel and tobacco.

Elena swallowed. “It was left to me,” she answered, cautious. “Who are you?”

He stepped a little closer, slow, not threatening. “Sebastián Morales,” he said. “Nice to meet you.”

He nodded toward a small house in the distance, partly hidden by scrub oak. “I own the plot next door. I knew your father. Stubborn as a mule. He planted these trees and gave up the minute the first real trouble showed up.”

Elena’s throat tightened at the bluntness, at the fact that a stranger could say what she’d never been allowed to say out loud.

She gestured toward the trunks. “Do you think they can come back?”

Don Sebastián studied her for a moment, not the trees. His gaze was sharp, measuring, like he was trying to decide if she was a passing visitor or the kind of person who stayed when things got hard.

“What do you know about trees, young lady?” he asked.

“Nothing,” Elena admitted. “But I can learn.”

A smile deepened the lines in his sun-browned face. “These trees need three things,” he said. “Water, care, and patience.”

He lifted his cane and tapped the rocky soil lightly. “The dirt up here isn’t as bad as folks say. But your father never built the right irrigation. He quit too soon.”

Elena looked at the slope, the distance to the river, the cracked ground. “I don’t have the money to build an irrigation system,” she said, and the honesty felt like a confession.

“But you’ve got two hands, don’t you?” he shot back. “And I’ve got knowledge. My grandfather worked orchards back when this valley was still more ranchland than subdivisions. He taught me a few tricks you might like.”

For the first time in a long while, Elena felt something lift inside her. Not a clean, bright hope, not something naïve. Something tougher. Something that felt like the first breath after being held underwater too long.

“Will you teach me?” she asked, softly enough that it felt like risking pride.

Don Sebastián’s smile turned sly. “Why not?” he said. “At my age, it’s easy to get bored. Besides, I want to see your brothers’ faces when these ‘dead chunks of wood’ start producing fruit again.”

That evening Elena drove home with a strange energy buzzing under her exhaustion. She didn’t have a plan yet, not a real one, but she had a direction, and that alone made her feel less like she was falling.

In the kitchen, she cooked out of habit, hands moving automatically, while her mind ran. She had a little money saved, not much. She could rent out the spare room on weekends to visiting nurses or seasonal workers, maybe even tourists who drove through wine country and wanted something “authentic.” She still had her grandmother’s recipes for preserves, the kind people bought at roadside stands and swore tasted like childhood.

She kept seeing that green beneath the bark.

When her brothers came back to the house to grab their things, they found her at the table with a library book open in front of her, pages marked with scraps of paper. It was a used book from the county library branch, stamped on the inside cover, a practical guide to fruit tree care with diagrams that looked like something a patient person drew over decades.

Mateo Raúl, the one everyone called Raúl, stared at her like she’d started speaking another language.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

Elena didn’t look up. “Learning.”

“And for what?” Andrés Javier, the one everyone called Javier, cut in. His tone was sharp, impatient, like he was already tired of her taking up air. “You’re not seriously going to waste your time on that hill, are you?”

Elena turned the page slowly before she answered. “I’m going to bring those trees back,” she said. “Something like that.”

Javier let out a laugh, the same laugh he’d given in the probate office, like a reflex. “Don’t be ridiculous. Sell that useless land and find a husband, Elena. That’s the only sensible thing.”

Elena closed the book. She looked them both straight in the eye, and the calm on her face surprised even her. It didn’t feel like a speech. It felt like a line being drawn.

“This house isn’t yours anymore,” she said evenly. “I want you to pack up and leave before dark.”

Raúl blinked. “You’re kicking us out?”

“I’m reminding you,” Elena said, steady, “that this is my life now, and my decision.”

She picked the book back up, but her eyes stayed on them, unflinching.

“And I’ve decided my road starts tomorrow at sunrise,” she continued, “with the trees everyone thinks are dead.”

That night, while her brothers hauled their things out with muttered protests and the kind of threats that were more about wounded pride than actual action, Elena did something she hadn’t done in years. She lay in bed and let herself picture the future without immediately correcting herself back into smallness.

She fell asleep thinking of water and green wood and the slow miracle of patience.

Dawn was barely breaking when Elena headed back up to the land. She carried an old cloth bag with a few basic tools: a small shovel, a rusty pair of pruning shears she’d dug out of the shed, a full water jug, and a notebook. She didn’t know anything about farming, not in the way her father would have respected, but she was determined to learn the way life actually taught people, by making them do the work with their own hands.

When she arrived, Don Sebastián was already waiting. He’d brought a stack of battered books and a wooden box filled with tools that looked older than the dirt road.

“Morning, kid,” he said, eyeing her improvised gear. “Looks like you’re serious.”

“I’ve never been more serious,” Elena replied, setting the bag down. The words felt true in a way that made her spine straighten.

Don Sebastián chuckled, approving. “First we figure out what we actually have.”

For hours, he taught her how to assess each tree. With practiced hands, he showed her how to scrape the bark gently to check the cambium, the thin green layer beneath the surface.

“See this,” he said, pointing to a cut on a branch. “This tree isn’t dead. It’s sleeping. When drought hits hard, sometimes they shut down to survive. Folks call it dormancy, but it’s more like… a stubborn refusal to quit.”

Elena wrote in her notebook like her life depended on it. In a way, it did. Every fact she learned felt like a brick in a foundation she’d never been allowed to build before.

“And you can wake them up,” she said, almost afraid to say it aloud.

“We can try,” Don Sebastián warned. “But it won’t be quick. They need consistent water, restorative pruning, and patience you can’t fake.”

They checked each tree methodically. Out of twenty-two, sixteen showed strong signs of life beneath the surface, four were in critical condition, and two were beyond saving.

“Not bad,” Don Sebastián concluded, wiping sweat from his forehead with the back of his sleeve. “Your father picked good varieties, but he planted them like the land owed him obedience. Land doesn’t care what you want.”

As he spoke, Elena noticed a patch of ground near one tree that looked slightly sunken, the way soil dips when something underneath has shifted.

“What’s this?” she asked.

Don Sebastián leaned on his cane and bent with difficulty, fingers probing the dirt. His face changed, just slightly, curiosity flickering.

“Interesting,” he murmured. “Help me dig.”

Elena used the small shovel, cutting into the earth. The soil was rocky, stubborn, but different here, darker in a way that made her think of moisture. Before she even hit half a meter, the blade struck something hard.

A dull, solid knock.

“Keep going,” Don Sebastián urged, and his voice had sharpened.

Elena dug faster. The dirt gave way in chunks. After a few minutes they uncovered a circular stone structure, fitted so tightly it looked like a careful hand had placed each piece.

“A well,” Elena breathed, and the word felt like a prayer she didn’t know she’d been saying.

Don Sebastián’s eyes narrowed as he studied it. “Old,” he said. “Real old. Could be from the ranchero days, when folks dug wells by hand and lined them with stone because it was all they had. People forget what’s buried out here. The valley looks flat from the highway, but it holds secrets.”

Elena’s heart pounded so hard it made her ears ring. “Do you think there’s water?”

“There’s only one way to find out,” Don Sebastián said.

He shuffled toward his house and returned with a rope and a bucket, moving with the careful urgency of someone who understood how rare this might be. Elena held her breath as they lowered the bucket down into the dark, listening to the soft whisper of rope against stone.

Five meters.

Then, clear and unmistakable, came the sound of water.

A hollow splash that seemed to echo up through the shaft like a promise.

Elena’s face broke open before she could stop it. Joy, shock, relief, all tangled together.

“Water,” she whispered, then louder, unable to hold it in. “There’s water.”

Don Sebastián’s eyes brightened, and for a second the old man looked younger, like he’d been waiting for this discovery for years without knowing it.

“And from the sound of it,” he said, voice thick, “it’s steady.”

Elena pressed her palm to the cool stone rim. Anger and grief rose together, sharp as thorns. How many valuable things had her father abandoned because he couldn’t tolerate the slow, humiliating work of restoring them? How many times had he taken disappointment and turned it into cruelty, as if cruelty could protect him from feeling like a failure?

“I’m going to clear it out and bring it back,” Elena said, and the certainty in her voice startled her. “Even if I have to do it with my own hands.”

Don Sebastián nodded once, solemn as a vow. “Then you’d better get ready,” he said. “Because this is where the real work starts, and this is where most people quit.”

Elena looked across the orchard, at the skeletal trees that weren’t dead, only waiting, and at the well that had been buried like a forgotten heartbeat.

She didn’t feel rich.

She felt chosen by something harder than luck.

And as the sun climbed higher, warming the stones under her hand, she understood, with a clarity that made her stomach flip, that her father hadn’t left her nothing.

He had left her the kind of inheritance that could either break a person or remake them, depending on what they decided to do next.

Over the following weeks, Elena split her time between three things: restoring the well, learning the truth about fruit trees, and earning enough money to keep the lights on without begging her brothers for anything. The work didn’t feel heroic. It felt like dirt under her fingernails that never quite washed out, like shoulders that ached even when she lay still, like waking up with the taste of dust in her mouth because the wind had blown all night.

In the mornings she climbed the hill before the sun got mean. The valley air could be cool at dawn, almost gentle, and she learned to love that brief window when the sky still held a soft blue and the orchard looked less like a battlefield and more like a promise. Don Sebastián met her there most days, moving slowly but steady, his cane tapping rock like a metronome. He had a way of watching without hovering, letting her do things wrong just long enough to learn why they were wrong, then correcting her with a short sentence that landed like a nail in wood.

They cleared brush first, because brush stole water and invited snakes, and because doing that simple, ugly work made everything else possible. Elena dragged branches into piles, burned what she could in a small metal barrel when the county allowed it, and hauled the rest down in her trunk in loads that made her old sedan groan. She learned which weeds were just weeds and which ones told you something about the soil underneath. She learned the smell of sun-warmed clay when you turn it, and the way rocky ground can still hide softness if you’re willing to dig for it.

Restoring the well was another kind of labor, the kind that made her feel like she was arguing with the past. The stone lining was solid, but silt and fallen debris had narrowed the shaft. Don Sebastián brought an old grappling hook and a flashlight with a cracked lens. Elena lowered the hook, pulled up muck, old leaves, and once, a rusted metal pan that looked like it had been dropped decades ago.

“People used to come up here,” Don Sebastián said, wiping his hands on his jeans. “Before the big pumps, before the irrigation district, before everybody thought water was guaranteed because a bill showed up once a month.”

Elena stared into the dark circle, listening to the faint, steady echo of water below. “So why did it get buried?”

“Same reason everything good gets buried,” he said. “Life got busy. Folks chased easier answers. Then the droughts came, and everyone pretended they were surprised.”

In the afternoons Elena drove into town and took a part time job at the county library branch. The building was small, beige stucco with a faded flag out front, and the air inside smelled like paper and old carpet and the faint sweetness of children’s snacks. She shelved books, checked out DVDs for retirees, helped people print job applications, and when she wasn’t needed at the desk, she sat at a table with a stack of agricultural guides and read like she was trying to catch up on a lifetime she’d been denied.

She learned words that felt too fancy for her mouth at first: cambium, scion, rootstock, dormancy, transpiration. She learned that a tree could look dead because it was conserving itself, that water stress changed everything, that pruning wasn’t punishment but direction. She read about grafting techniques used in old orchards up the coast, about how certain varieties survived heat better than others, about how microclimates could form on a slope if you understood wind and sun exposure.

At night she went home and did what she had always done, but with a different spine. She cooked simple meals, made lists, counted her savings down to the dollar. Her brothers had taken what they considered theirs, but they hadn’t taken her ability to work.

Some nights she cried from exhaustion and kept crying as she washed dishes, because there was no time to stop. Other nights she sat on the porch with her notebook and listened to the valley go quiet, the distant hum of highway traffic, the occasional bark of a dog, the low, steady chorus of crickets. That sound, steady and ordinary, began to feel like a kind of companionship.

The village started whispering about her. In this part of California, “village” didn’t mean cobblestone streets and church bells. It meant a few blocks of old storefronts, a diner that served coffee so strong it tasted like burnt comfort, a hardware store where men argued about irrigation parts like it was politics, and a community that watched each other’s lives the way people watch weather. Some folks mocked her. Some sounded curious but skeptical, like curiosity was something you had to hide behind a joke.

There she goes, the girl with the dead orchard.

You heard she’s sleeping up there now.

You heard there’s water.

People always said there was water.

Most of the whispers reached her in sideways ways, a cashier pausing too long, an older woman at the library peering at her boots, a man at the diner asking, too casually, “How’s that hill treating you?” Elena answered politely, but she kept her real thoughts to herself. She was learning that privacy was protection.

One of the few people who didn’t treat her like a spectacle was a middle aged librarian named Lucía Romero. She had gray streaks in her dark hair and the calm, observant eyes of someone who had seen more than this town could imagine. Her Spanish was soft and precise. Her English was perfect but carried a trace of something that suggested she’d lived in other places.

Elena had noticed her on the first day, the way she moved through the stacks like she belonged to them.

One afternoon Lucía came up to Elena’s table and set down a book without saying much at first. The cover was worn, the pages yellowed, and the title had been printed in a small university press font.

“This one doesn’t circulate,” Lucía said quietly. “I’m breaking the rule.”

Elena looked up, startled. “Why?”

“Because you’re not browsing for entertainment,” Lucía replied. “You’re building something with your hands.”

Elena ran her fingers over the cover. It was a study on unconventional grafting methods, a collection of techniques drawn from old orchard practices, some from Latin America, some from Indigenous communities, some from experiments people never bothered to publish because they weren’t trying to sell anything.

“I found it years ago at a used bookstore outside Fresno,” Lucía continued. “Back when I was still traveling. I kept it because it felt like a book that belonged to someone who would actually use it.”

Elena swallowed, moved by the quiet trust. “I don’t know if I’m worthy of that.”

Lucía gave her a look that was almost amused. “People who work this hard tend to be worthy. They just don’t believe it yet.”

Elena took the book home like it was fragile glass. That night she stayed up late reading about graft unions, about matching cambium layers, about sealing cuts with wax or clay in a pinch, about how you could strengthen a weak tree by taking life from a stronger one without killing either.

In the mornings, Don Sebastián taught her the parts of the work that couldn’t be learned from paper. He showed her how to dig narrow irrigation channels and line them with stone and packed clay, old methods that held water longer than bare soil. They were crude at first, uneven and leaky, but each day Elena got a little better. Her hands blistered and then toughened. Her back complained and then adapted. She began to understand that the body learns the same way a tree does: slowly, stubbornly, through repeated stress and recovery.

The first time water ran through one of those channels and reached a tree that hadn’t had a steady drink in years, Elena felt her throat tighten. The soil darkened around the roots like a bruise turning into healing. The ground seemed to exhale.

“Now comes the hard part,” Don Sebastián told her, wiping sweat from his brow. “Restorative pruning.”

He handed her the old shears. The metal was pitted and stiff, but it still bit.

“You cut away the dead so the sap feeds what’s still alive,” he said.

Elena stared at the branches. Cutting felt wrong at first, like she was injuring something she was trying to save, but Don Sebastián’s hands were steady, and his voice didn’t soften.

“If you don’t cut, the tree wastes energy trying to feed what will never come back,” he said. “Same thing happens to people.”

That line stayed with her. She thought of her father’s note, of his contempt, of how she had spent years feeding a man’s bitterness as if it could someday turn into affection.

She started cutting.

Each snip felt like a small goodbye. Branches fell, dry and brittle, and the tree looked even barer for a moment, like you’d stripped it down to its shame. But when Elena scraped the bark afterward and saw green beneath, she understood what Don Sebastián meant. The tree didn’t need more pretending. It needed a chance to put its energy where it mattered.

One afternoon, while they worked on a badly damaged plum tree, Don Sebastián pointed to a tiny green shoot emerging near the base of a stubborn apple trunk.

“Do you know what that is?” he asked.

Elena crouched, heart lifting. “New growth.”

“Better,” he said. “It’s the tree telling you it hasn’t quit. Now we help it.”

He glanced at the book Lucía had given her, which Elena carried in her bag wrapped in cloth like a sacred thing.

“This is where grafting matters,” Don Sebastián said.

He taught her like his grandfather had taught him, not with speeches but with hands. He cut a scion from a stronger branch, prepared the bud, made a clean slice in the weaker trunk, and fitted the pieces together with a patience that felt like prayer. Then he sealed it with clay and wrapped it with strips of cloth.

“What we’re doing,” he said, “is like a blood transfusion. We take strength from one part and give it to another part that needs it.”

Elena’s throat tightened. “Like a family should,” she murmured without thinking.

Don Sebastián’s gaze softened, but he didn’t pity her. He simply nodded as if she’d finally said something true.

“In nature, everything’s connected,” he said. “Trees share through roots. They warn each other about pests. They hold each other up in wind. Humans forget that lesson, then act surprised when they fall alone.”

By the end of the first month the well was clearer, the pulley system worked without sticking, and Elena’s channels, though imperfect, carried water where it needed to go. She upgraded what she could with scraps and secondhand parts, a length of hose from a yard sale, a couple of fittings from the hardware store that she bought with wrinkled bills. She learned to listen for leaks. She learned how a small crack could waste a whole day’s effort.

She also learned how quickly people’s attention shifted when they smelled value.

One afternoon Elena walked into Don Manuel’s hardware shop to buy more tubing. Don Manuel had been in town forever, with a belly that pressed against his apron and hands always stained with oil. He watched her cross the store like she was a story he wasn’t sure he believed yet.

“All of this is for the upper orchard?” he asked as he rang her up.

“Yes,” Elena said.

He lifted his eyebrows. “Your father used to say that land was only good for goats.”

Elena smiled, the kind of smile that didn’t ask for permission. “My father didn’t find the well.”

Don Manuel’s expression shifted, interest sharpening. “You found water up there?”

“Enough,” Elena replied carefully, because she could feel the danger in the question. In this valley, water was not a casual topic. Water started fights at barbecues. Water ended marriages. Water decided whether you kept your land or lost it.

Don Manuel lowered his voice anyway. “You should be careful who you tell.”

“I’m learning,” Elena said, and she meant it.

As she gathered her supplies, Don Manuel nodded toward the back of the store where a man about thirty was sorting parts with quick, competent hands. His hair was dark, his posture relaxed but alert, like someone who’d had to solve problems in places where no one was coming to rescue you.

“That’s my son,” Don Manuel said. “Martín Herrera. He studied agricultural engineering in Davis, then came home when the job market turned ugly. If you need help installing anything, he can do it right.”

Elena hesitated. Pride told her to refuse. Survival told her pride was expensive.

“If he’s willing,” she said.

The next afternoon Martín showed up at the orchard with a toolbox and a calm smile that didn’t try to charm her. He didn’t talk like a hero. He talked like someone who respected work.

“My father told me about your project,” he said. “I respect your courage.”

Elena felt her cheeks warm and hated that it happened. “It’s not courage,” she replied, adjusting her gloves. “It’s stubbornness. Sometimes they look the same.”

Martín took in what she’d done so far, his eyes moving from the well rim to the channels to the lines she’d marked around trees. “You’ve made a lot of progress in a short time,” he said, and it didn’t sound like flattery. It sounded like fact.

With Martín’s help, the irrigation system improved quickly. He brought a small used pump he’d found through a farm supply contact, and he rigged it with a solar panel setup he swore was not fancy, just practical. The first time the pump hummed and water moved through tubing to each tree, Elena felt something loosen inside her chest, like she’d been holding her breath for years.

Don Sebastián stood watching, pride in his eyes, the kind of pride that didn’t need to claim credit.

“Now comes the hardest part,” he warned once it was finished. “Waiting.”

He was right. The next weeks tested Elena in a way that blisters and rocks never could. Some trees showed promising signs, tiny shoots and cautious buds. Others stayed stubbornly asleep. Elena learned to check them without obsessing, to care without demanding instant proof.

Waiting was its own kind of labor.

One morning, as Elena checked the most stubborn apple tree, Don Sebastián arrived carrying a wooden box and a look on his face that said he’d been thinking too much.

“These trees are strong,” he said, “but to fully wake up, they need something special.”

He opened the box. Inside were packets of seeds labeled in neat handwriting, names Elena had never heard before. Some were in Spanish, some in an old script that looked like it came from another century.

“These are old varieties,” Don Sebastián explained. “My grandfather collected them. Some are nearly gone now. People stopped planting them because they don’t ship well, because they don’t look perfect in grocery stores. But they taste like the valley used to taste.”

Elena touched one packet as if it might break. “Why are you giving these to me?”

Don Sebastián’s eyes didn’t waver. “Because you’re the first person I’ve seen in a long time who doesn’t quit when the work gets ugly.”

He leaned closer, voice rough but gentle. “In these seeds is history. And you have the patience history requires.”

Elena’s hands trembled as she took the box. Responsibility settled over her, heavy and strangely beautiful.

“I’ll care for them like treasure,” she promised.

“They are treasure,” Don Sebastián said firmly. “And treasure attracts thieves. Keep that in mind.”

That afternoon Elena built a small nursery bed with scrap wood and wire mesh, a sheltered corner where the wind wouldn’t tear everything apart. She planted the seeds carefully, pressing each into the soil with reverence, watering lightly, marking rows with sticks and ink on tape. She felt ridiculous for how emotional it made her, but she also felt certain. Each seed was a quiet refusal to let the world erase what mattered just because it wasn’t profitable.

As the nursery began to show tiny green rises, Elena couldn’t help thinking how quickly she had changed. A month ago she had been a woman sitting in a probate office trying not to cry. Now she was someone who knew how to read a tree’s silence, someone who could fix a leak, someone who could tell the difference between dead wood and sleeping life.

The orchard began to shift. Irrigation channels curved between trunks like veins. The bark that had been gray and lifeless now hinted at color beneath the surface. In the nursery, small green promises pushed upward, delicate and stubborn.

“Do you know what the most valuable thing you have here is?” Don Sebastián asked one afternoon as they looked over the rows.

Elena wiped sweat from her forehead. “The well,” she guessed.

“Roots,” he answered, tapping the ground with his cane. “These trees have deep roots. They survived by refusing to quit, by searching for water where surface life couldn’t. Like you.”

That night Elena walked home under a sky full of stars, the kind of sky the valley still offered if you got far enough from the streetlights. She felt bound to that land in a way she couldn’t explain to anyone who hadn’t lost everything and then found something living under the ruins.

What she didn’t know, not yet, was that the valley was about to test her in a harsher way. Not with drought alone, but with the hunger drought created. In this place, when heat took away certainty, people didn’t only pray. They panicked. They bargained. They took.

Summer arrived early and cruel. The first heat wave hit like a slap, days where the air shimmered above the road and the wind felt like a hair dryer. The county issued water advisories. The news talked about record lows, about reservoirs that looked like cracked bowls. Farmers at the diner argued about allocations and blamed each other and blamed Sacramento and blamed God, as if blame could water a tree.

Javier’s olive grove began to show stress. Leaves curled. Fruit dropped early. Raúl’s fields, even near the river, suffered as the flow dropped and the soil baked hard as brick. Elena watched the valley change color, green fading into dusty silver.

By contrast, her orchard stayed stubbornly alive. The pump kept humming. The well kept breathing. The trees drank steadily, and slowly, almost shyly, life returned. New branches emerged from trunks that had once been bare. Bright leaves cast shade on ground that had been cracked and dry.

One July morning Elena reached the orchard and found Don Sebastián standing in front of an apple tree, frozen like he’d seen a ghost.

“Look at this,” he said when he saw her. His voice had a tremor in it, the kind old men try to hide.

He pointed to a small green bump on a branch.

Elena leaned in. For a second she couldn’t understand what she was seeing because it was too simple.

A tiny apple. No bigger than a marble, but perfectly formed.

Her breath caught hard enough it hurt.

“The first fruit,” Don Sebastián said, and his eyes shone.

Elena reached out and touched it with the lightest fingertip, afraid pressure might bruise the miracle away. Tears rose before she could stop them, not the helpless kind. The kind that came from relief so intense it felt like grief leaving the body.

“It’s beautiful,” she whispered.

“With the right care, it’ll ripen,” Don Sebastián said. “This is the first tree we grafted. Remember? The scion came from an old variety someone still keeps in a backyard down the valley. Rare now.”

Elena nodded, dizzy with the weight of what that meant. Proof. Not an argument, not a dream, not a stubborn plan on paper.

Proof.

They built a small mesh guard around the little fruit to protect it from birds and the harshest midday sun. Elena checked it like it was a heartbeat. Every morning. Every evening. Sometimes in between, just because she needed to see that it was still there.

News traveled faster than she expected. A few people came up the hill to see the “miracle,” some respectful, some skeptical, some pretending not to care while their eyes kept drifting to the well. Elena learned to smile without inviting anyone too close. She learned to answer questions without offering details that could be used against her.

Among the visitors was Doña Carmen Alvarez, the mayor’s mother, a woman whose approval carried more weight in town than any official announcement. She arrived in a wide brim hat, wearing clean jeans and boots that had seen real dirt. She walked the orchard slowly, taking her time, as if she didn’t want to be impressed too quickly.

“So it’s true,” she said at last, stopping in front of the apple tree. “You did what no one thought could be done.”

“There’s still a lot of work to do,” Elena replied.

Doña Carmen studied Elena’s face, then nodded as if she’d reached a conclusion about something deeper than trees.

“My son is organizing the local products fair in September,” she said. “You should participate.”

Elena let out a laugh that surprised her. “With what? I have one apple.”

“With your story,” Doña Carmen replied, and her voice softened. “Sometimes what people need isn’t a product. It’s proof that hard work still matters. You turned shame into something living.”

After that visit, people began showing up with offerings that weren’t money but mattered anyway. An older farmer brought a roll of shade cloth and said he had extra. A woman whose granddaughter had asthma offered unused fencing because she liked the idea of a pesticide light orchard. A teenager who worked at a farm supply place dropped off a box of drip line emitters and shrugged like it was nothing.

One afternoon a young woman named María, granddaughter of the town’s old herbal healer, showed up with a jar of greenish liquid that smelled like compost and wild plants.

“This is a bio fertilizer my grandma used to make,” María explained. “It strengthens roots and helps repel certain pests. I thought it might help your trees.”

Elena took the jar carefully, surprised by how emotional it made her. She had spent years feeling invisible, and now strangers were showing up because they wanted her to succeed. It was almost harder to accept kindness than cruelty. Cruelty had been familiar. Kindness required trust.

Martín became a regular presence too. He came with technical reasons, adjusting irrigation timing, checking the solar panel angle, tightening fittings, explaining how to prevent algae growth in the line. But Elena noticed other things as well, the way his eyes softened when he watched a new leaf unfurl, the way he listened when she talked about the seeds Don Sebastián had given her, like he understood that she wasn’t only rebuilding an orchard.

She was rebuilding herself.

One afternoon while Elena sorted seedlings in the nursery bed, Martín crouched beside her and pointed to the slope.

“I’ve been thinking,” he said. “This land has a microclimate. The slope protects it from some of the cold snaps, and the well gives you stability. Have you thought about diversifying beyond the usual varieties?”

Elena frowned. “Like what?”

Martín’s expression lit up, the way it did when he talked about ideas that felt bigger than the town’s привычные limits. “There are tropical cultivars adapted to Mediterranean climates,” he said. “Certain mango varieties, cherimoya, even papaya in protected spots. I wrote my thesis on it. It sounds crazy, but with the right protection and irrigation, it can work.”

Elena stared at him. The thought felt like a door opening to a room she hadn’t known existed.

“Why would I do that?” she asked, cautious.

“Because it makes you harder to crush,” Martín replied plainly. “If you rely on one crop, one buyer, one tradition, you become easy to corner. Diversity gives you leverage.”

Leverage. The word sat heavy in Elena’s mind. She didn’t like thinking in those terms, but she was learning that the world often forced people to.

Martín continued, gentler. “I can get scions from a research contact in Ventura. And we could build simple greenhouse frames with recycled materials. Nothing fancy. Just enough to protect them.”

Elena looked across the orchard at the old trunks. She thought of her father’s contempt, of how he had tried to teach her “effort” through humiliation. She thought of Don Sebastián’s seeds, of Lucía’s book, of the first apple swelling slowly toward ripeness. She thought of how quickly the town’s interest had turned from mockery to hunger.

“We can try,” she said.

Martín smiled, and the smile made something in Elena’s chest go strange and warm.

By mid August, the tiny apple had grown to a solid size. It wasn’t perfect by commercial standards. It had small blemishes, an uneven shape, a sun spot where the mesh didn’t shade enough. But to Elena it was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen because it was real. It was the sound of water at the bottom of the well made visible.

“It won’t be long now,” Don Sebastián said, voice full of quiet pride. “And it’ll be the first of many.”

Other trees began forming fruit too, small and tentative, as if the orchard was afraid to hope too quickly. The grafts took. The joints healed. The ancient varieties proved tough, stubborn, strangely suited to this hard land.

But the drought kept tightening its grip. With heat came desperation, and Elena felt it in the way men at the diner spoke louder, in the way trucks parked longer near her gate, in the way questions started to drift toward the well no matter how they were asked.

One afternoon Elena ran into Javier at the hardware store. His face was drawn, his eyes rimmed red from sleeplessness or stress. He didn’t greet her. He didn’t ask how she was. He didn’t have that kind of habit.

“I hear you’ve been working that useless plot,” he said.

“Yes,” Elena answered evenly.

“You’re wasting your time,” Javier snapped. “Sell it to me. I’ll pay fair.”

Elena stared at him, surprised not by the offer, but by how quickly he had moved from mockery to interest. “Why would you want dead chunks of wood?”

Javier glanced away. “I could use the land,” he muttered. “To expand. To shift some trees. Whatever.”

“It’s not for sale,” Elena said.

“Be reasonable,” he insisted, and his voice swung between pleading and ordering. “You don’t know what you’re doing. You’ll end up broke.”

Elena felt the sting, but she didn’t flinch. “Maybe I didn’t know much before,” she said calmly. “But I’m learning. And I found something interesting up there.”

Javier’s head snapped toward her. “What?”

“Water,” Elena said, watching his face. “An old well. Steady supply.”

The color drained from Javier’s face so fast it was almost frightening.

“How do you know this summer will be that bad?” he blurted, and the question revealed more than he intended.

“I read,” Elena said simply. “And I listen. They’re saying it could be the driest in decades.”

Javier’s jaw clenched. For a moment Elena saw something raw under his anger, something like fear.

That night Elena lay awake thinking about it. Was she selfish to have water while others were desperate? The thought made her stomach knot because she didn’t want to be that person. But then she remembered the buried well, the days digging, the money spent, the sweat that no one had offered to share.

The well had always been there. The work to restore it had not.

The next morning Elena walked up to the orchard early and found something that turned her thoughts cold.

Marks near the pump. A scuff on the tubing. A tug on the wiring that didn’t belong.

Martín knelt and inspected it, his face tightening. “Someone tried to mess with it,” he said. “Not a kid. Someone who knows enough to be dangerous.”

Elena’s throat went dry. “Who?”

Martín exhaled slowly. “In a drought, it’s rarely one person. It’s pressure. Pressure makes people do stupid things.”

Don Sebastián’s voice was low. “Desperation can turn a neighbor into a thief overnight.”

They decided to take shifts watching the orchard. Don Sebastián in the morning. Martín in the afternoon. Elena set up a small tent and sleeping bag near the well, telling herself it was temporary, telling herself she could handle a few nights of discomfort.

But the truth was simpler. She was afraid to leave it alone.

On the first night she slept there, the wind shifted and leaves rustled like whispering mouths. She lay awake longer than she wanted to admit, listening to every small sound, forcing herself not to imagine shapes in the darkness.

Near midnight she heard footsteps, soft but deliberate, approaching the well area.

Elena sat up, heart hammering, and reached for her flashlight without turning it on. She kept her breathing shallow. She didn’t want to announce herself. She wanted to know.

A shadow moved near the pump. There was a faint metallic scrape, like someone testing something.

Elena’s pulse hammered so hard she felt dizzy, but she didn’t run. She didn’t scream. She had lived too long under someone else’s authority to waste energy on panic. She slid out of the sleeping bag, stepped out barefoot onto cold ground, and moved behind the nearest trunk, keeping the orchard between her and the figure.

The scrape came again. Closer.

Elena snapped the flashlight on.

The beam cut through the dark and landed hard on the person by the pump.

He jerked, froze, and lifted a hand to shield his face.

Raúl.

Her brother.

For a split second Elena felt nothing. Then pain hit, cold and sharp, like someone pressing a thumb into a bruise.

Raúl stood there with his jacket collar up and his hair a mess, a pair of pliers in his hand. His eyes were red. He looked less like the confident man from the probate office and more like someone who had been carrying fear around like a backpack full of stones.

“Raúl,” Elena said, her voice steady even though her hands wanted to shake. “What are you doing here?”

Raúl swallowed hard. “Elena, I… I wanted to talk.”

Elena tilted the light slightly so it still held him, but didn’t blind him. “Did you come to talk,” she asked, “or did you come to cut?”

He glanced down at the pliers like he’d forgotten they were there. His throat worked.

“I’m not cutting,” he said quickly. “I just… I wanted to look. I wanted to know if the lock was really necessary.”

Elena let out a soft laugh with no warmth in it. “It is,” she said. “Because you’re standing here with pliers.”

Raúl’s shoulders sagged. For a moment he looked like a boy caught doing something he didn’t want to admit even to himself.

“I didn’t come to destroy anything,” he said. “I came because of Javier.”

Hearing Javier’s name made Elena’s stomach tighten.

“What did he do?” she asked.

Raúl looked around, as if the orchard itself might be listening. Then he spoke fast, like speed could make the words less shameful.

“He’s losing it,” Raúl said. “He’s deeper in debt than you think. The bank is talking about seizing things within weeks. He panicked. He said if he doesn’t get water, he’ll lose everything. He said he’d do anything.”

Elena held the light steady, but her fingers tightened around it until they hurt.

“So why are you here?” she asked. “To warn me? Or to clear the way?”

Raúl shook his head hard. “To stop him.”

Elena studied him, weighing the truth in his face the way she’d learned to weigh life in a tree’s bark. She wanted to believe him. Wanting didn’t make it safe.

“To stop him while holding pliers,” she said quietly.

Raúl’s jaw clenched. “I was going to,” he admitted, and the confession came out like bile. “If you refused to give more water, I was going to open the lock for Javier. Let him take it. At least then I could control it, keep him from destroying the whole system.”

Elena felt anger flare, but beneath it was something worse: disappointment. She had offered cooperation. She had offered dignity. And still they came at night, like thieves.

“Do you hear yourself?” Elena asked. “You’d steal from me to protect me.”

Raúl’s eyes flashed with something raw. “I haven’t slept either,” he burst out. “You think you’re the only one exhausted? You have water and now everyone calls your name like you’re some kind of saint. Me and Javier, we’re the failures. We’re watching everything die.”

Elena’s heart softened for a heartbeat, then hardened again. She had learned the difference between empathy and surrender. Surrender was what her father had trained into her. She was done with that.

“You can be scared,” she said, voice low and clear. “But you don’t get to turn me into the victim so you feel less like one.”

Raúl stood there, breathing hard. The wind moved through the leaves. Far off, a dog barked once and then went quiet again.

Elena stepped closer and picked up the pliers from where he’d let them fall, sliding them into her jacket pocket.

“From now on,” she said, “these stay with me. You don’t come near the well alone again. If you want to talk, you talk in daylight. In front of everyone.”

Raúl nodded, humiliation and relief mixing in his face like he didn’t know which one he deserved.

“Can you give more water?” he asked, and the question sounded like a plea he hated himself for needing.

Elena looked at him and thought of the months of work, the way her hands had learned new strength, the way the orchard had become something bigger than her pride.

“I will,” she said, and Raúl’s face lifted like a drowning man seeing shore.

“But not like this,” Elena added, cutting the hope clean in half. “We do it under rules. A schedule. Measured flow. Records. Locks. If you or Javier cross the line, it stops.”

Raúl stared at her as if he’d finally realized the sister he’d dismissed was gone.

“You’ve gotten hard,” he said quietly.

Elena nodded. “Yes,” she replied. “Because water isn’t just water.”

Raúl’s face tightened. “I’m sorry,” he said.

Elena didn’t answer with forgiveness she didn’t feel yet. She only said, “Go. Before someone sees you here and twists it into something else.”

Raúl turned away, took a few steps, then stopped and looked back, as if there was one more thing lodged in his throat.

“Elena,” he said, voice lower than the wind. “Javier isn’t only desperate. He’s talking to people from that company. The one from the fair.”

Elena’s blood ran cold. “What company?”

“Agroindustrias,” Raúl said, the name tasting like something bitter. “He said if you don’t sign something, he’ll help them by making you scared.”

Elena’s mouth went dry. “How?”

Raúl shook his head. “I don’t know. But I heard him say ‘fire’… and ‘accident.’ I came tonight because I was afraid he’d actually do it.”

For a moment Elena stood perfectly still. The flashlight beam felt too small against the darkness that suddenly seemed full of possibilities she didn’t want to imagine. She kept her voice steady anyway, because steadiness was a choice, and she was learning to choose it.

“Go,” she repeated, firmer now.

Raúl walked away faster, almost a retreat, disappearing down the path into the black.

Elena stayed by the well, listening to the faint sound of water far below, steady and alive. The sound had comforted her before. Now it sounded like a warning as well.

She went back into the tent, grabbed her phone, and didn’t let herself think too long.

She called Martín.

It rang until she almost thought he wouldn’t answer, and then his voice came through thick with sleep.

“Elena?”

“Listen,” she said quickly, keeping her voice low but firm. “Raúl was here. Javier is planning something. Agroindustrias is involved. I need you up here now.”

There was a pause, a shift in the silence, and then Martín’s voice sharpened fully awake.

“I’m coming,” he said. “Ten minutes.”

Elena ended the call, hands steady now because the decision had been made.

She opened her notebook and wrote a single line under the day’s date, the way someone writes a fact they want to remember without emotion because emotion can blur the edges.

“Tonight: Raúl came. Javier tied to outsiders. Sabotage risk rising. From now on, the orchard needs defense.”

She looked out into the orchard. The trees stood quiet in the dark, trunks once called dead wood now solid and stubborn, roots gripping deep. She realized, with a clarity that made her chest tighten, that this was no longer only a story about revival.

It was a story about what happens when something abandoned becomes valuable, and the people who dismissed it suddenly decide it belongs to them.

From far below she heard the sputter of Martín’s motorcycle climbing the hill, cutting the night open.

And Elena understood that the real fight was only beginning.

Martín’s motorcycle reached the gate with a sputter and a cough, then cut off. Elena heard his boots on rock before she saw him, fast steps that didn’t try to be quiet. He came up the path with his tool bag slung over one shoulder, hair still messy from sleep, face sharpened by the kind of worry that doesn’t ask questions twice.

“Elena,” he said, low and urgent. “Where are you?”

“Here,” she answered, stepping out of the tent so he could see her in the dim beam of her flashlight. “By the well.”

Martín crossed the last few yards in three strides. He looked at her first, not the pump, like he needed to confirm she was intact.

“Are you hurt?” he asked.

“No,” Elena said. Her voice sounded steadier than she felt. “But it’s getting worse.”

Martín crouched by the pump without wasting time. He ran a hand along the tubing, checked the wiring with the quick, practiced movements of someone who could feel a problem before he saw it. The moon was thin, barely enough light to make shadows. He clicked on his own flashlight and angled it across the lock.

“It’s still holding,” he murmured, then looked up at Elena. “Tell me everything. Slowly.”

So she did, but not with drama. She told him about Raúl showing up with pliers, about the words that mattered, about Javier’s panic, about the company circling like a hawk. She said the word fire once, and it made the air feel colder.

Martín’s jaw tightened so hard a muscle jumped in his cheek. He didn’t curse. He didn’t lecture. He just absorbed it, eyes fixed on the pump like he wanted to memorize every bolt and vulnerability.

“Okay,” he said at last. “We do two things right now. First, we make it harder to touch this without making noise. Second, we make sure you’re never alone up here at night again.”

Elena let out a breath she hadn’t realized she was holding. “How?”

Martín opened his bag and pulled out a heavier lock than the one on the gate, and a coil of plastic coated steel cable that looked like it belonged on a boat trailer. He held them up like evidence he’d already seen the future coming.

“I stopped at the shop after you called,” he said. “My father keeps these. I had a feeling.”

Elena’s throat tightened in a way that had nothing to do with fear. Someone had thought about her before she had even asked.

Martín threaded the cable around the pump housing and through the metal frame that anchored it, then looped it around a thick rock outcrop like he was tying the well to the earth itself. He didn’t hurry, but he moved with purpose, making each step clean, final. When he snapped the lock shut, the sound was small and sharp in the night, a click that felt like a boundary.

“It won’t stop someone determined,” he said, wiping his hands. “But it slows them down. And slowing them down gives you a chance to catch them.”

Elena stared at the lock, then at Martín. “You talk like you’ve dealt with this before.”

Martín’s mouth pulled into something that wasn’t quite a smile. “Out here, everyone’s dealt with some version of it,” he said. “Sometimes it’s theft. Sometimes it’s pressure. Sometimes it’s family. Same root.”

A gust of wind rattled dry leaves overhead. Elena imagined the orchard as a living thing listening, taking notes.

Martín glanced toward the dark slope that fell away toward the valley lights, then back to her. “We set a watch schedule,” he said. “Me and Don Sebastián can take turns. But if anyone comes up here again, we document it. We don’t turn this into rumors. We turn it into facts.”

Elena nodded slowly. She wasn’t naive anymore. She had learned that feelings could be twisted into stories people used against you. Facts were harder to bend.

“What about Javier?” she asked.

Martín’s eyes held hers, steady. “If he’s serious about sabotage, you stop treating him like a brother you can save with kindness,” he said quietly. “You treat him like a man who might ruin you because he can’t stand watching you stand.”

Elena flinched at the truth in it, even though she had already felt it in her bones.

Martín softened his tone just a little. “You don’t have to be cruel,” he added. “You just have to be clear.”

They stayed up until the sky began to lighten, sitting on overturned buckets near the tent, listening for movement that never came. Elena watched Martín’s profile as dawn crept in. He looked calm now, but she could see the contained anger under it, the protective instinct that didn’t need an audience.

When the first pale light touched the hill, Elena walked toward the well again, compelled to check it like a pulse. Dew clung to young leaves and made the orchard smell alive, sharp and clean. She leaned over the stone rim and listened.

The water was still there. Steady.

Then she saw the ground beside the pump and stopped.

Footprints.

Heavy boot prints, square heeled, pressed into the softer soil near the tubing. Not hers. Not Martín’s. Not Don Sebastián’s. The pattern was too crisp, too new.

Elena crouched and traced the edge of one print with her fingertip. The soil was damp. The person had been here recently.

Martín came up behind her and followed her gaze. His whole body went still.

“Someone came after we locked it,” he said.

Elena placed a small stone beside the print like a marker, then stood. She didn’t feel panic now. She felt the cold focus that comes when fear turns into direction.

“We start today,” she said.

Martín nodded once. “You treat the well like the heart,” he replied. “People won’t come for the trees first. They’ll come for the water.”

Around eight, Don Sebastián arrived, cane tapping, eyes sharp. He looked more tired than usual, not in his body but in the way his gaze moved over the orchard as if he could already see what greed would do to it if Elena let it.

She showed him the footprints.

He didn’t ask whose they were. He didn’t pretend to be surprised. He only said, “When something has value, people start calling it for everyone. Then they find a way to make it for themselves.”

Elena swallowed. “Who do you think it is?”

Don Sebastián’s mouth flattened. “Doesn’t matter,” he said. “What matters is you learn to say no the way pruning shears cut. Clean. Final.”

Elena looked down at her hands, the dirt packed into the creases, the small cuts that had become ordinary. “I don’t want to become cold,” she admitted.

Don Sebastián’s eyes held hers. “Cold isn’t saying no,” he said. “Cold is letting them destroy everything and then crying like you didn’t see it coming.”

The words landed deep, not because they were harsh, but because they were true.

By noon, the orchard felt different. Not the trees, not the water, but the attention. People passed by the gate who had never walked this road before. They paused too long. They stared at the pump and the tubing like they were doing math in their heads. Some asked polite questions that didn’t match their eyes.

Elena answered lightly, kept her face calm, and watched them leave. She knew now that attention was a kind of fire. It could warm you, or it could burn you down.

That afternoon, a sleek black car crawled up the dirt road, slow and deliberate, raising a soft cloud of dust that hung in the air like a warning.

It stopped at the gate.

A man stepped out in a clean suit that looked wrong against the scrub and rock. He carried a briefcase and wore the same polished smile Elena had seen once before, back when everything still felt like a miracle instead of a battleground.

Agroindustrias.

He looked around as if he were calculating a price, eyes sliding from the trees to the channels to the well, then settling on Elena.

“Ms. Mendoza,” he called, voice smooth. “Good to see you again.”

Martín stepped closer to Elena, not touching her, but close enough that she could feel the quiet support.

Don Sebastián stood a few feet back, still as a fence post.

“I’ll be brief,” the man continued, as if time was his property. “I heard you’ve been talking to the university.”

“We’ve spoken,” Elena said.

He smiled wider. “Very idealistic. Very… noble. But ideals don’t pay for infrastructure, security, lawyers.”

Elena didn’t flinch. “What do you want?”

The man opened his briefcase and pulled out a document, holding it with two fingers like it was something generous.

“We don’t want to buy the land,” he said. “We want to buy the rights.”

Elena kept her voice steady. “What rights?”

“Exclusive distribution and commercialization rights,” he replied. “You keep ownership of the orchard. You keep your little project. But you sell us the rights to export, brand, packaging, and to develop the varieties at scale.”

Develop. The word sounded clean. The way he said it made it sound like exploitation without the shame.

Martín’s voice cut in, low and sharp. “You mean you want to own the future of what she built.”

The man lifted a hand as if to soothe. “We want to partner,” he corrected smoothly. “With investment.”

He looked back at Elena, eyes narrowing just a fraction. “You’re going to be stretched, Ms. Mendoza. Your brothers are under pressure. The bank doesn’t pause for family feelings. The valley is drying. And you’re up here sleeping in a tent like this is a camping trip.”

Elena felt the pressure behind his words like a hand on her throat. She didn’t show it.

“You sign,” he said, “and you get money immediately. Real money. Infrastructure, fences, cameras, security. You stop worrying about sabotage. You stop worrying about accidents.”

Don Sebastián’s cane tapped the rock once, a small sound that felt like a warning bell.

Elena stared at the paper. For a half second she felt the temptation of relief, not greed, relief. The kind of relief that comes when someone offers to lift a weight you’ve been carrying alone.

Then she heard his earlier phrase again in her head, develop at scale, and she saw her trees not as living survivors but as units on a spreadsheet, stripped of story, stripped of soul. She saw the ancient seeds Don Sebastián had entrusted to her treated like novelty stock until they were used up.

Elena did not take the document.

“I won’t sign,” she said.

The man’s smile cooled without disappearing. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” Elena answered. “I’m sure.”

He slid the paper back into the briefcase and snapped it shut like closing a door.

“Then I hope you don’t regret it,” he said, and his voice was still polite, which made it worse. “In this region, water isn’t just water. Water is power.”

He turned, got into the car, and drove away, dust curling behind him like a slow threat.

Elena didn’t move for a moment. Her heart hammered, but her face stayed calm.

Martín looked at her. “Are you okay?”

Elena stared at the well, then at the trees. “No,” she said quietly. “But I’m not backing down.”

Don Sebastián’s hand came down lightly on her shoulder. “Now you’re really starting,” he said. “Drought is simple. Greed is the hard part.”

In the days that followed, Elena worked like someone trying to outrun a storm. She and Martín reinforced the pump housing. Martín installed a motion light powered by a small solar panel, bright enough to turn any night visitor into a silhouette. Don Sebastián helped her set a watch routine that didn’t depend on trust alone. They kept notes. Times. Small details. Not because Elena loved paperwork, but because she was learning that surviving attention required proof.

Through it all, the tiny apple ripened, growing heavier, coloring slowly into a warm, uneven red that looked more human than supermarket fruit. Elena checked it every morning like a ritual.

And then, one afternoon near the end of August, she held it in her hand and knew.

It was time.

She invited the people who had actually been part of the work, not the people who had arrived when the work turned valuable. Don Sebastián came in his nicest shirt, the one he only wore for weddings and funerals. Martín brought a bottle of homemade cider. Lucía arrived with her calm eyes and a quiet smile. María came with her jar of green fertilizer and a small basket of herbs. Even Raúl and Javier showed up, though their faces were tight, like they were attending something they didn’t know how to name.

Under the softening sun, the small group gathered around the apple tree. Elena wore a simple white dress that had once belonged to her mother, not for drama, but because it felt like claiming something she had been denied. She held a small basket in her hands, palms sweating.

“Four months ago,” Elena began, voice steady but not loud, “this place was a cemetery for abandoned trees. My father left it to me as punishment, convinced I would fail. Today we’re picking the first fruit.”

She paused, letting the moment breathe. She could hear leaves whispering overhead, the faint hum of the pump, the quiet breathing of the people around her.

“Not because it was easy,” she continued. “Because we refused to quit.”

She reached up, cradled the apple gently, and twisted until it came free with the softest snap.

For a moment no one spoke.

The apple sat in her palm, small, imperfect, glowing like proof.

Martín lifted the cider. “A toast,” he said. His voice carried warmth and steel together. “To Elena, who taught us there are no dead trees, only hearts that quit too soon.”

They raised glasses. Even Raúl and Javier lifted theirs, though more slowly, as if pride had to swallow first.

“And to new beginnings,” Don Sebastián added, eyes sliding toward the brothers, “because it’s never too late to straighten a tree that grew crooked.”

Elena cut the apple into tiny pieces with a small paring knife. She gave each person a slice, making sure everyone received something, even if it was only a bite. Symbol mattered. She had learned that from grafting.

When she handed Javier his piece, he hesitated.

“I don’t know if I deserve this,” he murmured, avoiding her eyes.

“It’s not about deserving,” Elena said softly. “It’s about sharing.”

That small ceremony didn’t fix everything. It didn’t erase years of contempt. But it marked a turning point that the orchard itself seemed to feel, as if the land was watching to see what kind of person Elena would choose to be now that she had power in her hands.

The next day, Doña Carmen visited again, this time with her son, the mayor. He walked the orchard with an official calm, but Elena noticed the way his eyes kept returning to the well and the irrigation layout.

“Impressive,” he said at last.

“We’ve worked very hard,” Elena replied.

“And it shows,” he said. “I’m here to make a proposal. We want your orchard to be the centerpiece of this year’s local products fair.”

Elena’s stomach tightened. “But we barely have production.”

Doña Carmen cut in gently, firm as stone. “It’s not only about product. It’s the story. People need to see that adaptation is possible. They need hope that doesn’t feel like a commercial.”

Elena looked at Martín, then at Don Sebastián. She could feel the risk like a weight. Opening the orchard to the public meant more eyes, more hunger, more opportunity for the wrong kind of attention. It also meant legitimacy, and legitimacy could be armor.

“Give me time to talk with my team,” she said.

They agreed.

The weeks leading up to the fair were chaos wrapped in dust. Elena and Martín marked walking paths with stones and rope, keeping visitors away from fragile graft unions and young seedlings. They built small wooden signs describing varieties, not too technical, not too poetic, just honest. Lucía helped her write them, choosing words that felt human. Don Sebastián insisted on adding one sign that simply read, in Spanish and English, Patience is also work.

Elena barely slept. She worked with her hands all day and planned by lamplight at night, running numbers in her notebook until her eyes blurred. She worried about parking. About liability. About whether people would respect boundaries. About whether the pump would hold under extra use.

One evening, as she reviewed her task list, Martín stood in her kitchen doorway holding a folder. His face was serious in a way that made Elena’s instincts tighten.

“I need to show you something,” he said.

He spread papers across her table. Photos. Printouts. Notes.

“I’ve been researching those old varieties,” he explained. “The ones from Don Sebastián’s seeds, the grafts you’ve already done. Do you realize what you might have up there?”

Elena stared at the pages, mind trying to catch up. “Fruit trees,” she said, cautious.

Martín shook his head. “A genetic treasure,” he replied. “Some of those varieties are critically endangered. Protected agricultural heritage. If they’re what I think they are, they’re valuable in ways beyond money.”

Elena’s skin prickled. “Valuable how?”

Martín tapped a page showing a description of a rare apple cultivar, its original region, its traits, its conservation status. “In Europe, in certain programs, varieties like this are monitored. Preserved. Studied. If you can prove you have living specimens, there are grants. Partnerships. Legal protections.”

Elena sank into her chair, stunned.

“I sent photos and notes to an old professor of mine,” Martín continued. “He wants to come to the fair. Not to buy. To see. To talk. To maybe propose a collaboration.”

Elena stared at him. The orchard had been a way to survive. Now it was becoming something that might outgrow her.

“That sounds like trouble,” she said, and she meant it honestly.

Martín’s eyes softened. “It’s also a shield,” he replied. “If you’re tied to a legitimate research program, it gets harder for people to corner you into bad deals. They can still try, but it changes the game.”

The fair morning arrived clear and bright, the kind of late summer day that looked beautiful until you remembered how little water the land had received. Elena slept in the orchard the night before, not because she wanted to be dramatic, but because she didn’t trust anything left alone anymore.

By midmorning, the first visitors arrived. Families with kids, older couples in wide brim hats, farmers in dusty boots pretending they weren’t curious. A local food truck parked near the gate selling tacos and lemonade. Someone brought a portable speaker and played old country songs softly, not enough to overpower the leaves. The air smelled like dust, sun warmed fruit, and the faint sweetness of cider.

Don Sebastián stood under a tree explaining grafting in slow, patient words, his cane leaned against the trunk like it belonged there. Martín guided technical visitors through the irrigation design. Lucía helped Elena answer questions without giving away more than she needed to.

Elena discovered something that surprised her. She could tell the story naturally. Not like a pitch, not like a speech, but like truth. People leaned in when she described scraping bark and finding green. They went quiet when she talked about the well. They smiled when she described the first bud, the first leaf, the first apple.

“This tree taught me that life finds a way,” Elena said at one point, standing near the apple tree. “It just needs someone willing to believe long enough to give it a chance.”

By noon, a small group arrived with notebooks and cameras. Martín’s eyes lit up.

“University people,” he whispered. “And journalists too.”

The attention made Elena’s stomach tighten, but she kept her face calm and her hands busy, guiding, explaining, grounding herself in the work.

An older professor with glasses stepped forward after walking the orchard carefully. His shoes were too clean for the hill, but his gaze was respectful.