“Rosa, why don’t you go help in the kitchen? You’d be more comfortable with the staff.”

The fork stopped halfway to my mouth. Crystal caught the light above us, the kind of chandelier that cost more than my first house, and for a second all I could hear was the faint clink of silverware dying around the room.

Seventy people in tuxedos and evening gowns went still.

My future son‑in‑law grinned like he’d just told the best joke of his life. His Harvard ring flashed when he lifted his glass, chest puffed out in that way rich men do when they’re sure the world is laughing with them.

Across the table, his mother Patricia let out this tinkling laugh that sounded like broken glass. “Oh, Christopher, you’re terrible,” she said, but her eyes slid over me like I was something someone had forgotten to wipe off the floor.

I was sixty‑two years old, standing in a navy dress I’d bought on sale at Macy’s, in the grand ballroom of the Wellington Country Club on the west side of Houston, and every set of eyes in that room pivoted toward me, waiting to see what the housekeeper would do.

I folded my cloth napkin very carefully and set it down beside my plate.

Then I stood up.

And for the first time in a long, long time, I decided I would not swallow this one.

My name is Rosa Martinez, and I have been cleaning other people’s messes, one way or another, for forty years.

When Miguel and I crossed the border into Texas, we had one duffel bag, two pairs of shoes between us, and a piece of paper with a Houston phone number written in my cousin’s handwriting. I had calluses on my palms from packing fruit; Miguel’s back ached from bending over construction rebar twelve hours a day.

The first thing I bought with my own money in this country was not a dress, not a couch, not a television.

It was a gray plastic cleaning bucket.

One bucket, one mop, one dream.

People like Patricia Bennett have no idea what a bucket can build.

Miguel started out mowing lawns in neighborhoods with names that sounded like movie sets: Lakeview Estates, Magnolia Creek, Stonebridge. I started by cleaning one house on Saturdays for a woman who treated her golden retriever better than her nanny.

Word travels fast in those gated communities. If you show up on time, if you scrub the grout until it remembers what color it’s supposed to be, if you keep your mouth shut about the things you see and hear, your phone starts to ring.

Back then I thought if I worked hard enough, if I was careful enough, if my English was polite enough, I could earn my way out of being invisible.

I know better now.

What I didn’t know, standing there with that first bucket in my hands, was that one day I’d be in a ballroom full of people whose homes I could have cleaned and whose toilets my employees actually did clean, listening to one of them tell me to go back where I belonged.

The irony would have been funny if it didn’t hurt so much.

Our daughter, Isabella, came to us eleven months after we arrived in Houston. I like to joke that she was our first legal resident. Born at Memorial Hermann, seven pounds two ounces, a head full of dark hair, lungs strong enough to rattle the windows.

From the day she could walk she wanted to help. She’d toddle along behind me dragging a rag, wiping at baseboards that were already clean. When she was six, she used to crawl under the kitchen table after a client’s party and pick up napkins and dropped crackers like it was a treasure hunt.

I hated that part.

Not because of the work. Work, I understood. Work was our prayer, our promise, our way of saying thank you to a country that let us stay.

No, what I hated were the looks.

The way some homeowners would step around my daughter like she was clutter. The way they would talk about investments, vacations, college funds, as if the woman scrubbing their oven and the little girl beside her did not have a future that would ever include those words.

One afternoon, after a woman in River Oaks told Isabella, “You’re going to grow up to be such a good little helper, just like your mamá,” my daughter climbed into our old pickup truck and went quiet.

“Miha?” I asked, buckling her seatbelt.

She stared out the window at the line of manicured trees. “I don’t want to be a helper,” she said finally. “I want to be the one who hires helpers.”

Something inside me shifted.

That night I told Miguel, “We’re not just going to survive here. We’re going to build something. She’s not going to grow up thinking this is all she can be.”

Miguel kissed my knuckles, the same knuckles that bled bleach into the cracks. “Then we build,” he said. “We build until they have to see us.”

I made two promises that night at our tiny kitchen table, with the cheap vinyl peeling at the corners.

One: Isabella would have opportunities I never did, even if I had to work myself into the ground.

Two: I would teach her that no matter how much money someone has, nobody is better than her.

Years later, I realized there was a third promise buried under those two.

I would never let anyone put us back in a corner and tell us to know our place.

That’s why the rehearsal dinner at the Wellington cut as deep as it did.

It wasn’t just what Christopher said.

It was that I had seen it coming, piece by piece, and kept telling myself I was overreacting.

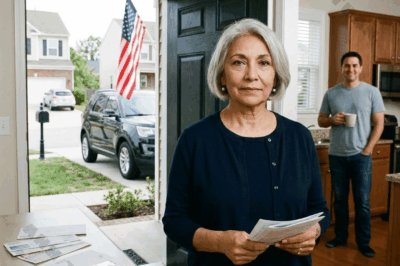

The first time Isabella brought Christopher home, it was a Sunday in early spring. The grass in our front yard was just waking up from winter; Miguel had edged the driveway twice that week, nervous energy coming out through the line trimmer.

I’d cooked enough food for an army: chicken enchiladas, arroz, beans, guacamole, charro beans the way my mother taught me. I’d even gone to Target and bought new plates so we wouldn’t be serving our daughter’s fancy lawyer boyfriend on the chipped ones we’d used for twenty years.

He stepped out of his black Tesla in pressed khakis and a pale blue button‑down, the kind of clothes that never see a wrinkle because someone else irons them. His hair was the right kind of effortless, his smile perfectly calibrated.

“Mr. and Mrs. Martinez,” he said, offering Miguel his hand.

Miguel wiped his own on his jeans before taking it. “Call me Miguel,” he said.

Christopher’s handshake was firm, practiced. When he pulled back, I watched him rub his palm discreetly against his pants.

Like my husband’s skin had left a mark.

Isabella saw it too. I could tell by the way her shoulders tightened, the way she distracted herself by fussing with the casserole dish in my hands.

She was glowing that day. Twenty‑nine years old, Doctor of Pharmacy degree framed in her apartment, student loans almost paid off because she’d worked two jobs all through college and refused to buy herself anything that wasn’t on sale. She looked at Christopher like he’d hung the moon.

“Mama, Papa, this is Christopher Bennett,” she said, eyes shining. “The man who makes me laugh more than anyone.”

He did make her laugh. I saw that. He asked about her patients, about her favorite classes in pharmacy school, about growing up in Houston. He complimented my food and said his firm had a few Latino associates who would die for enchiladas this good.

It was all very smooth.

But later, when Miguel was outside showing him the backyard and Isabella and I were alone at the kitchen sink, she whispered, “Please, Mama. Please like him. I know he’s… different. But he loves me. He really does.”

I dried my hands on a dish towel and cupped her face like I did when she was little. “If he loves you, I will find a way to like him,” I said. “That’s my job.”

I meant it.

I just didn’t know yet how expensive that job would feel.

The engagement itself was a whirlwind. One night in mid‑June, my phone buzzed with an incoming FaceTime while I was training two new hires at a medical office downtown. When I saw Isabella’s name, I slipped into the stairwell to answer.

She filled the screen, eyes wet, breathless, a hand pressed to her chest.

“Mama,” she gasped. “He proposed. Christopher proposed.”

A diamond the size of a raindrop flashed on her finger.

I leaned against the cool concrete wall, tears prickling my own eyes. “Ay, miha,” I whispered. “My beautiful girl.”

She’d done it. The girl who used to fall asleep over algebra homework at our wobbly kitchen table had built a life that included Harvard‑educated attorneys and rooftop proposal dinners at downtown steakhouses.

I should have been nothing but happy.

But with the ring came Patricia.

Patricia Bennett arrived in our lives on a wave of expensive perfume and entitlement so strong you could taste it.

She was sixty‑something, like me, but we might as well have been different species. Her hair was a perfect helmet of platinum, her smile practiced for charity galas and board photos. She wore pearls the way other women wore cardigans casual, effortless, as if she were born tangled in them.

At our first meeting, a brunch at a trendy restaurant in River Oaks, she shook my hand the way people do when they’re touching something delicate and slightly unpleasant.

“So you’re Isabella’s mother,” she said, eyes sliding over my simple blouse and the calluses that no amount of lotion would ever erase. “You must be so proud.”

“I am,” I said. “Every day.”

She didn’t ask what I did for a living. Not then. She asked Miguel if he liked sports and Christopher if work at Harper Steele & Associates was keeping him busy. She told Isabella she’d booked the ballroom at the Wellington Country Club before the engagement was even official because “all Bennett weddings are held there, dear. It’s tradition.”

When the check came, she placed a manicured hand over it and said, “This one’s on the Bennett family.”

I thanked her, because that’s what you do.

Later, as we walked to the parking lot, Miguel murmured, “She never looked you in the eye.”

“I noticed,” I said.

My daughter looped her arm through mine. “She’s just… old‑school,” Isabella said. “She doesn’t mean anything by it. Right, Mama?”

I smiled for her sake. “Of course, miha.”

I lied for her sake, too.

The four months between the proposal and the rehearsal dinner were like being nibbled to death by ducks.

No single comment was a dagger. It was the accumulation.

Patricia never used my name. To her, I was “Isabella’s mother,” or, more often, “her.”

“Does your mother own a formal dress, dear?” she asked one afternoon while looking over the guest list at Isabella’s apartment. “We should make sure she has something appropriate for the club.”

“She has a dress,” Isabella said, jaw tightening. “And yes, it’s appropriate.”

When we went dress shopping, Patricia suggested I stay in the waiting area.

“The salons can be overwhelming,” she said with a brittle smile. “Too many mirrors. Too much chaos. Why don’t you sit and rest, Rosa?”

I’d spent my life hauling vacuums up three‑story stairs, but apparently a carpeted bridal salon was too much for me.

Still, I sat. I watched my daughter try on ivory gowns while Patricia clapped and dabbed her eyes, going on about “classic silhouettes” and “timeless elegance.”

At one point, Isabella stepped out in a mermaid‑style dress that hugged her curves and made her look like she’d stepped out of a magazine.

“What do you think, Mama?” she asked, cheeks pink with excitement.

I opened my mouth, but Patricia spoke first.

“It’s stunning,” she said, then glanced at me. “It might be a bit… much for your family, dear. Perhaps something more understated would be better.”

My daughter’s shoulders sagged.

I stayed quiet.

That night, alone in our bedroom, Miguel said, “Rosa, this woman does not respect you.”

“I know,” I said.

“Then why are we letting her talk to you like that?”

Because Isabella is in love, I wanted to say. Because she has the life we dreamed for her, and I don’t want to be the reason anything cracks. Because I spent too many nights filling out citizenship forms and praying over paperwork to lose my temper now over a dress.

Instead I said, “It’s only for a few months. Once they’re married, it will settle.”

Miguel stared at the ceiling, his jaw tight. “Or it will get worse.”

He wasn’t wrong.

I just didn’t want him to be right.

The Wellington Country Club sat behind a security gate and a row of oak trees, its white columns gleaming in the late afternoon sun the night of the rehearsal dinner.

Miguel wore his one good suit, the navy one we’d bought when Isabella graduated from the University of Houston College of Pharmacy. I wore a simple navy dress I’d saved for, with a string of faux pearls Isabella had given me for Mother’s Day three years earlier.

“I feel like I’m walking into someone else’s movie,” I whispered as we pulled into the circular drive, passing valets in black vests.

Miguel squeezed my hand. “Then we’ll be the best supporting characters they’ve ever seen,” he said.

Inside, the ballroom was everything Patricia loved: crystal chandeliers, towering arrangements of white roses, linen tablecloths so crisp they looked ironed straight onto the tables.

I noticed the place cards first.

Christopher’s parents at table one, along with Isabella and Christopher, his law partners, and the pastor who would officiate the wedding. Table two: partners’ spouses and a few Bennet cousins. Table three: a family Patricia spoke of reverently, the Vanderbilts of some oil fortune.

Our names Rosa and Miguel Martinez were printed in looping calligraphy and placed at table twelve. The very back. Near the swinging doors to the kitchen.

My sister Ana and her family were at table eleven.

So close, and yet not the same.

“Absolutely not.”

Isabella appeared in a swish of champagne‑colored silk, cheeks flushed. She looked like a champagne flute come to life. “You should be up front,” she said, snatching up our place cards. “You’re my parents. This is ridiculous.”

“Miha, it’s all right,” I said. “We can see the front just fine from here.”

“No, Mama.” Her eyes shone with frustrated tears. “It’s not all right.”

Before I could stop her, she marched across the room toward table one.

I watched Christopher intercept her halfway, his hand closing around her wrist. Not harsh, but firm. My daughter pulled away, her brows drawn together.

Patricia glided over, pearls swinging. She said something I couldn’t hear, her lips tight with disapproval.

Isabella’s face drained of color.

Patricia patted her shoulder like you do with a child who is misbehaving in public, then drifted away to greet another guest.

My daughter came back to us a minute later, our place cards still in her shaking hands.

“Table twelve is fine, Mama,” she said, voice too bright.

“Bella,” I whispered. “What did they say?”

She shook her head and forced a smile. “Let’s just try to have a nice evening.”

My napkin felt rough under my fingers.

I should have pushed harder right then.

I didn’t.

I told myself what I’d been telling myself for months: it’s only one night.

Dinner started with a salad and a speech.

Christopher’s father, tall and tanned from golf, told a story about Christopher winning a sailing regatta at sixteen, how determined he’d been even as a boy. Patricia followed with a little monologue about Bennett family traditions, weddings at the club, how thrilled they were to welcome Isabella into the fold.

No one mentioned Miguel and me.

No one talked about Isabella working the pharmacy counter on Christmas Eve or staying up until two in the morning to study for pharmacology exams, then opening at the coffee shop at six.

It was as if she had somehow appeared, fully formed, in Christopher’s social circle, like a decorative piece you pick up at Pottery Barn.

I pushed a cherry tomato around my plate and tried not to stare at the glittering ring on my daughter’s left hand.

That ring, I realized, had become our hook. The thing that kept pulling her deeper into a life that did not see us.

When the filet mignon arrived, I focused on cutting my meat into small, precise pieces. The plates were heavy, the china pattern delicate. I’d dusted this same pattern before in other homes. The irony stung.

Seventy guests chatted and laughed under those chandeliers. At table twelve, Miguel and I ate quietly, trying to disappear.

Then I heard my name.

“Rosa and Miguel at table one? Are you insane?”

Patricia’s voice carried from the bar across the room, sharp as a broken wine glass. The acoustics of the ballroom turned private complaints into public announcements.

I looked up.

She stood with Christopher, both of them facing the mirrored bar. Isabella was in the restroom; her empty chair at table one glared at me like an accusation.

“Isabella’s making a scene about the seating arrangement,” Patricia said, her lips barely moving, but the microphone of the room carrying every word. “It’s exhausting.”

Christopher took a sip of his drink, jaw tight. “It shouldn’t matter where they sit,” he said. “They should be grateful they’re even here, considering…”

My stomach clenched.

“Considering what?” Patricia prompted.

He snorted. “That her mother cleans houses.”

The word “cleans” came out like a slur.

Patricia gave a small, horrified laugh. “Christopher,” she said, hand on his arm, but she didn’t sound horrified. She sounded delighted. “We cannot have them at the family table. What would people think? Your partners are at table two, the Vanderbilts are at table three. Imagine if someone asks what Rosa does for a living. ‘My future mother‑in‑law scrubs toilets.’”

He laughed then. A full, ugly laugh.

“That’ll go over well at the firm,” he said.

They laughed together.

Mother and son.

My face burned. I could feel Miguel’s hand slide over mine under the table, his fingers squeezing so hard it almost hurt.

“Should we go?” he murmured.

My throat felt tight. “No,” I whispered. “Not here. Not now. For Bella.”

But I was wrong about that, too.

Isabella had come back from the restroom while they were talking.

I saw her freeze halfway between the door and table one, eyes fixed on Christopher and his mother reflected in the bar mirror.

Her shoulders squared.

She walked straight up to them, lips a thin line, and said something I couldn’t hear.

Christopher rolled his eyes.

He said something back and gestured toward our table.

Her voice rose.

Conversation died down around the room like someone turning a dimmer switch.

That was when he made the mistake he would remember for the rest of his life.

“Your mother needs to understand her place, Isabella.”

His voice rang through the ballroom, every syllable clear.

“This is the Wellington Country Club. There’s a hierarchy. There’s protocol.”

He turned, arm sweeping toward us at table twelve like he was a magician revealing his assistant.

“Rosa,” he called across the room, loud and casual, like he was asking me to pass the salt. “Why don’t you go help in the kitchen? You’d be more comfortable with the staff.”

Silence.

Utter, total silence.

Someone’s fork hit a plate with a sharp clink and then nothing, just the hum of the air‑conditioning and the rushing sound of my own blood in my ears.

Patricia laughed first.

“Oh, Christopher, you’re terrible,” she trilled, but she was smiling, eyes bright.

She agreed.

I felt Miguel’s chair scrape back beside me. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Isabella go white, then red, then white again.

In some other version of my life, the younger version, I might have stayed seated. I might have swallowed the burn in my throat, told myself it was only one night, told myself not to embarrass my daughter.

But I was not the woman with the first bucket anymore.

I was the woman responsible for four hundred and twenty paychecks going out on time every other Friday. I was the woman whose staff scrubbed the marble floors of that very club at two in the morning so rich people could drink champagne on them without ever looking down.

I was the woman who had promised, in a tiny rented kitchen twenty‑nine years earlier, that no one would make my daughter feel small.

My chair scraped back.

I picked up my napkin and folded it, corners sharp, the way I fold the corners of a bedspread when I’m making a hospital corner.

Then I stood up.

“No,” I said.

At first, it came out soft.

Christopher actually frowned, confused. “Excuse me?”

I lifted my chin.

“No,” I repeated, louder. “I will not go to the kitchen.”

A murmur rippled through the room.

“I’m not staff here, Christopher,” I said. “I’m your fiancée’s mother. I’m a guest. I was invited.”

“Well, technically, you were included because ”

“Mama.”

Isabella was suddenly beside me, her fingers lacing through mine so tight it hurt.

“Let’s go,” she whispered. “Please. Let’s just leave.”

“Isabella, don’t be ridiculous,” Patricia snapped, pushing back her own chair. “Your mother is making a scene. Christopher was joking.”

“He wasn’t joking.” Isabella’s voice shook, but she didn’t sit down.

“I heard you both at the bar,” she said, louder now, voice carrying to every corner of that ballroom. “I heard every word.”

Christopher’s face went pale. “Bella, we were just ”

“You called my mother a toilet scrubber,” she said, each word like a stone. “You said you were embarrassed of her. Of him.” She nodded toward Miguel. “Of my parents, who worked themselves to the bone so I could have opportunities you took for granted.”

“Isabella, lower your voice,” Patricia hissed.

“No.”

My daughter reached for her left hand.

The room held its breath.

She twisted the three‑carat diamond ring off her finger. Under the chandelier light, it flashed like something alive.

“I will not lower my voice,” she said. “I will not sit quietly while you humiliate my family. I will not marry someone who thinks my mother isn’t good enough to sit at the same table as him.”

She set the ring down on her dessert plate.

The small, hard clink of diamond against china sounded louder than Christopher’s insult had.

“You’re being hysterical,” Christopher protested, reaching for her. “You’re throwing away ”

“Don’t touch me.” Isabella stepped back, out of his reach.

She looked around the room, at the partners, the Vanderbilts, the country‑club wives with their pearls and frozen smiles.

“My mother worked two jobs to pay for my schooling,” she said, voice steady now. “She scrubbed floors during the day and worked in a restaurant at night. My father mowed lawns in a hundred‑degree Houston summer. They never missed a single one of my school plays or my softball games or my graduations. They loved me when I had nothing to offer but myself.”

Her voice cracked, just once.

“That’s more than you’ve ever done, Christopher. You love what I represent. A smart, acceptable wife for your career. You don’t love me.”

“Isabella,” he tried again. “Be reasonable.”

She turned back to us, eyes bright with tears and something else.

Resolve.

“I’m done being reasonable,” she said. “Come on, Mama. Papa. We’re leaving.”

She took my hand, then Miguel’s.

We walked out of that ballroom together, the three of us in a crooked little line, past tables full of people who suddenly found their salads very interesting.

Behind us, I heard Patricia’s outraged voice, Christopher swearing under his breath, the murmur of scandal starting to bloom.

I didn’t look back.

The night air outside was thick and hot. In the parking lot, under the yellow glow of the lampposts, Isabella finally broke.

She collapsed against our old Toyota, sobbing.

“I’m so sorry,” she choked. “I’m so, so sorry, Mama.”

“Miha, no.” I pulled her into my arms, feeling her shoulders shake. “You have nothing to be sorry for.”

“I should have stopped this months ago,” she said into my shoulder. “I should have defended you sooner. I saw how they treated you and I just… I wanted it to work. I wanted to believe he loved me enough to be better.”

Miguel wrapped his arms around both of us.

“Tonight, when it mattered, you defended us,” he said. “That’s what counts.”

His voice was rough.

For the first time since we came to this country, I watched my husband’s eyes fill with tears.

We took Isabella home that night to our small house in Alief, the one with the sagging front step and the hydrangea bush that refuses to die no matter how brutal the summer gets.

She curled up on her childhood bed, under the faded Selena poster that still clung to the wall, and cried herself to sleep.

Miguel and I sat at the kitchen table until nearly two in the morning, a pot of coffee between us, my navy dress draped over the back of a chair.

“She made the right choice,” Miguel said, staring at the dark window where our reflection floated over the backyard.

“I know,” I said.

My heart ached anyway.

I’d seen the Pinterest board on her phone, the photos of the dress she’d chosen, the honeymoon beach she’d picked out on a map. I’d watched her practice signing “Isabella Bennett” on scrap paper, not because she needed to change her name, but because girls have been practicing new signatures since forever.

Now all of that was gone.

“I hate that her first big love ends like this,” I whispered.

Miguel nodded slowly. “Better it ends now than after children and a mortgage,” he said. “He showed her who he is before it was too late.”

I wrapped both hands around my coffee mug, letting the heat seep into my fingers.

“He also showed us something,” I said.

“What’s that?”

I looked down at my hands the same hands that had once clutched a single gray bucket and felt an old promise stir.

“That we were right to build our own table,” I said. “Even if they never wanted us at theirs.”

Christopher called twenty‑three times over the next three days.

Isabella didn’t answer.

He left voicemails that swung wildly between remorse and rage: apologies, excuses, guilt trips about deposits and caterers and how humiliated he felt.

“Do you know what it’s like to have seventy people watch your fiancée throw your ring at you?” he demanded in one message. “You embarrassed me, Isabella.”

She held the phone out for me to hear that one, her eyebrows raised.

“Imagine,” she said dryly. “Me embarrassing him.”

On day four, Patricia called.

When I saw her name flash across my screen, I almost let it go to voicemail.

Instead, I answered.

“Hello?”

“This is your fault,” she said by way of greeting. Her voice was cold enough to fog glass. “You raised her to be ungrateful. To not understand opportunity when it’s handed to her.”

“I raised her to understand respect,” I said, keeping my voice even. “Which your son does not.”

“Christopher can have any woman he wants,” she snapped. “Isabella should be begging for forgiveness.”

“She’s not begging anyone,” I said. “She has self‑respect. I made sure of that.”

Patricia gave a sharp, humorless laugh.

“Self‑respect,” she repeated. “Is that what you call walking away from a Bennett? Do you have any idea what our family name carries in this city?”

I looked out the kitchen window at the line of our work vans parked along the curb, each one with our logo discreetly painted on the side.

“Yes, Patricia,” I said softly. “I know exactly what your family carries.”

I ended the call before she could respond.

Miguel, drying dishes at the sink, raised an eyebrow.

“You lasted longer than I would have,” he said.

I shrugged, feeling strangely calm.

“The more she talks, the more she tells on herself,” I said.

The following week, the phone calls changed.

First came a man who introduced himself as Robert Chen from Harper Steele & Associates.

“I represent Christopher Bennett,” he said, his tone formal. “He’s asked me to reach out regarding a settlement.”

“We don’t need a settlement,” Isabella said when I put the call on speaker. “There’s nothing to settle. We didn’t get married.”

“Yes, but there are wedding expenses, deposits,” he said. “Mr. Bennett is willing to forgo any claim if you’ll agree not to discuss the events of the rehearsal dinner publicly. We understand you may have recorded a portion of the evening.”

Isabella looked at me.

She had, in fact, recorded a portion. Not the table scene that had happened too fast but the conversation at the bar. She’d pulled out her phone when she saw Christopher and Patricia whispering and hit record on instinct.

“I recorded your client’s mother making fun of my mother’s job,” she said. “I recorded your client laughing about it.”

“I see,” he said, clearing his throat. “Well. Perhaps we can discuss terms.”

“No,” Isabella said, and hung up.

I expected that to be the end of it.

I was wrong.

Two weeks after the rehearsal dinner, on a Wednesday afternoon so humid the air felt like soup, Isabella knocked on our front door instead of just walking in.

When I opened it, she stood on the porch in her pharmacy scrubs, her hair pulled back, eyes clear.

“Mama,” she said. “I need to ask you something. And I want the whole truth.”

“That sounds serious,” I said, stepping aside. “Come in. I’ll make coffee.”

She sat at the kitchen table, right where she’d done her homework, where she’d studied for the MCAT she decided not to take, where she’d written scholarship essays.

Miguel came in from the backyard, wiping dirt off his hands.

“What’s going on?” he asked.

Isabella took a deep breath.

“Your cleaning business,” she said, looking at both of us. “Rosa’s Cleaning Service. Or Rosa’s Commercial Services, or whatever it’s called now.”

I blinked.

“Okay,” I said slowly.

“It’s bigger than I thought, isn’t it?” she said. “Like… a lot bigger.”

Miguel and I exchanged a look.

We hadn’t exactly hidden the truth. But we hadn’t put it in neon either.

We didn’t talk about numbers with our daughter because we never wanted her to feel like she owed us anything. We wanted her to know her success belonged to her.

“Sit down, miha,” I said, pouring coffee into three mismatched mugs.

She sat.

I sat across from her and wrapped my hands around my mug, the way I always do when I’m about to say something that matters.

“I started Rosa’s Cleaning Service in 1985,” I said. “One woman, one bucket, one client.”

Isabella smiled faintly at that. She’d heard the story before, but never like this.

“For twenty years I cleaned houses,” I continued. “Good houses. Big houses. I was reliable. Thorough. I never stole so much as a paperclip. People talk. They started recommending me to their friends. By 2005, I had fifteen employees.”

I could see the flicker of surprise in her eyes.

“By 2010, we had fifty,” I said. “That’s when we pivoted to commercial cleaning. Office buildings. Medical facilities. Schools.”

“Mama,” she said slowly. “How many employees do you have now?”

I took a breath.

“Four hundred and twenty,” I said.

Her coffee cup froze halfway to her mouth.

“What?”

“Four hundred and twenty,” I repeated. “Full‑time and part‑time. Plus some contractors. We have contracts with thirty‑two medical facilities, eighteen schools, and forty‑seven office buildings.”

She leaned back in her chair like someone had pushed her.

“Forty‑seven,” she echoed.

“Including the Taylor Building downtown,” Miguel added.

I hesitated.

“That’s where Harper Steele & Associates is,” Isabella said slowly. “Christopher’s firm. Right?”

“Yes,” I said. “Our company has cleaned their offices every night for eight years.”

Her mouth fell open.

“How much is that contract worth?” she asked, her voice barely above a whisper.

“About twelve million,” Miguel said quietly. “Over eight years. Around one and a half million per year.”

She stared at us.

“Twelve million dollars,” she said. “Mama… Papa… Does Christopher know this?”

I shook my head.

“No,” I said. “Very few people know the details. The company is in Miguel’s name. I’m listed as founder. We don’t advertise much. We get business through reputation.”

“So when he was laughing about you scrubbing toilets,” she said slowly, “your employees were literally scrubbing his toilets every night after he went home.”

“Pretty much,” Miguel said.

Isabella started to laugh.

Then she started to cry.

Then she did both at the same time, tears streaming down her face as she doubled over.

“Oh my God,” she gasped. “Oh my God, Mama. This is insane.”

“There’s more,” Miguel said.

“More?” she said weakly.

“The Wellington Country Club,” he said. “We have the exclusive cleaning contract. Twelve years now. About twenty‑two million over that time.”

She stared at him like he’d grown a second head.

“Twenty‑two million dollars,” she repeated. “At the place where they told you that you weren’t good enough to sit at the front table.”

I nodded.

“Do they know?” she asked. “Does Patricia know?”

“No,” I said. “The board knows who owns the company. The members? They see uniforms. They don’t see owners.”

She stood up and walked to the kitchen window, staring out at the hydrangeas and the row of white vans lined up at the curb.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” she asked quietly. “Why didn’t you tell me how big it was? How many people depend on you?”

“Because we didn’t want money to be the loudest thing in the room,” I said. “We wanted you to work hard for your own success. To know that your degree, your job, your life were yours, not ours.”

She rested her forehead against the cool glass.

“But I could have thrown this in Christopher’s face,” she said. “At the rehearsal dinner. At the bar. I could have said, ‘My mother doesn’t just scrub toilets. She owns the company that scrubs your toilets. She pays four hundred and twenty people to scrub them.’”

I stood up and went to her, laying a hand on her shoulder.

“That’s not who we are,” I said softly. “We don’t throw money around to make people feel small. That’s what Patricia does. That’s what people like Christopher do.”

“But they made you feel small,” she said, turning to look at me. “They humiliated you. They humiliated Papa. You just stood there and took it.”

“I stood there,” I said. “And then I stood up.”

She let out a shaky breath.

“So what do we do now?” she asked.

Miguel leaned back in his chair, crossing his arms.

“We do nothing,” he said. “We let it go. You dodged a bullet. Christopher showed you who he is. Be grateful and move on.”

I nodded, even though a small, dark part of me wanted to do anything but let it go.

That part of me remembered every time a client had spoken about me as if I weren’t in the room.

It remembered Patricia’s laugh.

It remembered the way Christopher said “kitchen” like it was a prison cell.

But it also remembered the four hundred and twenty families whose rent depended on our contracts.

Revenge might have felt good for a moment.

Losing a contract worth twelve million dollars because of pride would not.

“We move forward,” I said. “That’s what we’ve always done.”

Fate, however, had a different plan.

Three days later, my phone rang again.

“Mrs. Martinez?” a man’s voice said. “This is Robert Chen from Harper Steele & Associates.”

I almost laughed.

He cleared his throat. “I apologize for the intrusion, but I’m calling about a… sensitive matter.”

“Go ahead,” I said, my curiosity outweighing my annoyance.

“It’s regarding our cleaning contract with Rosa’s Commercial Services,” he said. “We’ve just learned that you own the company.”

There was a tiny pause before the word “own,” like he still couldn’t quite believe it.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

Silence stretched for a beat on the line.

“I see,” he said finally. “Mrs. Martinez, I want to apologize. Personally. If I had known that one of our attorneys was engaged to the daughter of the woman who owns the company that keeps our offices running, I would never have… well.”

“You would never have what, Mr. Chen?” I asked. “Let him treat my daughter badly? Or just let him get caught?”

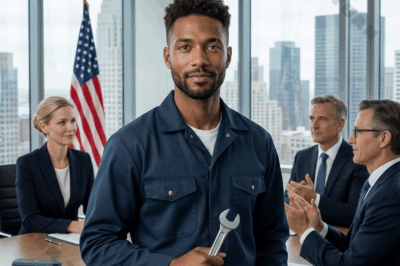

There was another pause.

“To be clear,” he said slowly, “I’m not calling on Christopher’s behalf this time. I’m calling on the firm’s. Our contract with your company will not be affected by… personal matters. We value your business. Your staff are professional, discreet, and excellent at what they do.”

“That’s good to hear,” I said.

“I’m also calling to inform you that Christopher Bennett is no longer with our firm,” he said. “We asked for his resignation this morning after some of the senior partners learned about the incident at the Wellington Country Club. About how he spoke to you. About what he said to Isabella.”

I sat up straighter.

“Excuse me?”

“One of our partners received the audio recording of the bar conversation from Isabella,” he said. “We reviewed it. A number of us have also known Patricia Bennett socially for years. Hearing her speak about you that way, and hearing Christopher laugh… it was disgusting, Mrs. Martinez. It doesn’t reflect our values.”

I let that sink in.

I had spent decades believing people like Patricia could behave however they wanted without consequence.

Turns out, sometimes, consequences arrive late.

“Thank you for telling me,” I said.

“There’s more,” he added.

Of course there was.

“The Wellington Country Club board would like to meet with you this Friday, if you’re available,” he said. “They’ve reviewed the security footage from the rehearsal dinner. They also now understand that your company holds their cleaning contract. They’d like to discuss… adjustments.”

My stomach dropped.

“Adjustments,” I repeated. “They want to cancel, don’t they?”

“No, Mrs. Martinez,” he said. “They want to increase it.”

On Friday morning, Miguel and I drove back to the Wellington Country Club.

The last time we’d been there, we’d left through the side door with our daughter’s heart in pieces.

This time, we walked in through the front entrance as invited guests.

I wore the same navy dress. Miguel wore the same suit. But something in the way we carried ourselves felt different.

We weren’t there as someone’s plus‑one.

We were there as partners.

The receptionist led us to a wood‑paneled conference room that smelled faintly of old money and lemon oil. Four people sat around the table: three men and one woman, all in their fifties or sixties, all wearing the kind of clothes that never look off‑the‑rack.

“Mr. and Mrs. Martinez,” the man at the head of the table said, standing to shake our hands. “I’m Charles Whitmore, board president.”

“Thank you for seeing us,” I said.

“I’ll get right to the point,” he said, sitting back down. “We’ve learned what happened at the Bennett rehearsal dinner. Several members reported the incident. We’ve also reviewed the security footage.”

I felt my cheeks flush all over again.

“What Mr. Bennett said to you was unacceptable,” he continued. “What Mrs. Bennett found amusing was unacceptable.”

“I appreciate you saying that,” I said carefully.

“We understand that you own Rosa’s Commercial Services,” the woman on the board said. “We were frankly surprised. We’ve always assumed the company owner was… well…”

“Someone else,” I finished for her, not unkindly.

She smiled, embarrassed. “Yes.”

“Our club has standards,” Whitmore said. “One of those standards is treating everyone on this property with respect members, staff, guests, vendors. We failed you on that standard.”

Miguel cleared his throat. “We’re not here for an apology,” he said. “What’s done is done. Our concern is our staff. They don’t deserve any fallout from this.”

“Agreed,” Whitmore said. “Which is why we’re not canceling your contract. We’d actually like to extend it. Increase the scope. We’d like to lock in a ten‑year agreement at twenty‑five million, with annual adjustments for inflation.”

Twenty‑five million.

The number floated in the air between us.

Our key number, I realized, had just changed.

“Additionally,” the woman said, glancing at her notes, “we’d like to feature your company in our member magazine. A profile on how you built the business, your commitment to your employees. We think our members should know the story of the person who keeps their club in pristine condition.”

My throat tightened.

“You don’t have to do that,” I said.

“We do,” Whitmore said firmly. “We have to show that we mean what we say about respect.”

He shifted in his chair, looking uncomfortable for the first time.

“We’re also revoking Patricia Bennett’s membership,” he added. “Effective immediately.”

I blinked.

“What?”

“We’re a private club,” he said. “We can choose our members. Mrs. Bennett’s behavior toward you, both as a guest and as a business partner, violates our standards. This isn’t about revenge, Mrs. Martinez. It’s about who we are as an institution. If we allow members to treat you that way, we allow them to treat any staff member that way. We’re drawing a line.”

I thought about the dishwashers I’d seen hunched over tubs in the kitchen, the servers who’d kept their eyes down when Patricia snapped her fingers at them.

Maybe, just maybe, our humiliation had bought them a sliver of protection.

Miguel squeezed my knee under the table.

“We accept your offer,” he said quietly.

I nodded.

“Thank you,” I said. “Not just for the contract. For seeing us.”

Whitmore inclined his head.

“It was past time,” he said.

Life didn’t turn into a fairy tale after that.

We still had payroll to make every two weeks. Trucks still broke down. Employees still called in sick. I still got up at five a.m. most mornings to answer emails before heading out to walk job sites.

But something in our little house shifted.

Isabella stopped jumping when the phone rang.

She threw herself into her work at the pharmacy with a kind of fierce calm. She signed up for an extra certification course. She started running in the evenings, earbuds in, cheeks pink when she came back through the front door.

Two months after the rehearsal dinner that never turned into a wedding, she met Daniel Kim.

He came into the pharmacy on a Tuesday with a sleepy‑eyed nephew on his hip and a question about a dosage.

“I’m a pediatrician at Texas Children’s,” he said, setting a prescription bottle on the counter. “I just want to double‑check something. New practice guidelines.”

Isabella glanced at the bottle, then at him.

“Most doctors don’t admit they need a pharmacist,” she said, teasing.

“I’m not most doctors,” he said, smiling.

He came back the next week with another question.

The week after that, he came back with coffee.

“Look,” he said, setting a cardboard cup carrier on the counter. “I have a selfish ulterior motive. I’d like to ask you out. But even if you say no, I’ll still need your help keeping my patients safe, so I’m hedging my bets with caffeine.”

Isabella laughed in a way I hadn’t heard in months.

When she told me about him that night, sitting on the edge of my bed like she used to when she was a teenager, she twisted the hem of her T‑shirt instead of a ring.

“He asked about you and Papa,” she said. “He asked what you do. When I told him you own a cleaning company, he said, ‘That’s incredible. Building a business from nothing is harder than med school.’”

I felt my eyes sting.

“Sounds like a smart man,” I said.

On their first date, he picked her up from our house.

He arrived five minutes early, in jeans and a button‑down, holding a small bouquet of grocery‑store flowers that somehow meant more than any florist arrangement Christopher had ever sent.

He shook Miguel’s hand like he meant it. He hugged me when Isabella introduced us.

“So you’re the woman behind four hundred and twenty employees,” he said, eyes warm. “I’ve heard about you.”

“Only good things, I hope,” I said.

“The best,” he said.

Six months later, they got engaged.

No country club.

No black‑tie dinner.

Just our backyard, strings of white lights Miguel bought at Home Depot, folding chairs borrowed from the church, and a borrowed arch covered in flowers from Ana’s garden.

Daniel’s parents flew in from California for the weekend. His father, a retired postal worker, spent an afternoon with Miguel talking about tomatoes and fertilizer. His mother, a former elementary school teacher, stood next to me at the kitchen counter pinching empanada dough like she’d been doing it her whole life.

“Thank you for raising such a strong daughter,” she said at one point, flour on her hands. “Daniel needs someone who knows who she is.”

During the ceremony, Isabella wore a simple lace dress she’d ordered online. She walked down an aisle of grass in the backyard she’d played in as a child.

When Daniel said his vows, he promised to respect her, to listen when she spoke, to stand beside her family, not above them.

I believed him.

After they said “I do,” Isabella tossed her bouquet into the air.

It landed, of all places, right in the old gray bucket I’d kept all these years, now repurposed as a planter by the back fence.

Everyone laughed.

I laughed, too, but there was a tightness in my chest.

One bucket. One life.

Sometimes the universe has a sense of humor.

I still clean houses sometimes.

Not because I have to I have a management team now, supervisors and route planners and safety officers who make sure our four hundred and twenty employees have what they need but because it keeps me grounded.

There’s Mrs. Caldwell in West University, whose husband died ten years ago and who still cries sometimes when she finds his old baseball caps in the back of the closet. There’s the Nguyen family in Bellaire, who leave me notes in perfect cursive thanking me for “taking such wonderful care of our home.”

On quiet mornings, I still lace up my old sneakers, grab a caddy of supplies, and knock on their doors.

They greet me by name.

They look me in the eye.

Those are the houses that remind me why I started.

Every once in a while, though, I see Patricia.

Houston is a big city, but old money circles are small. I spotted her once at Whole Foods, comparing two brands of organic olive oil. She saw me across the aisle, froze for a split second, then turned her cart around and wheeled it down another lane without a word.

I watched her go, feeling… nothing.

No satisfaction. No bitterness.

Just distance.

Last I heard, Christopher was working at a much smaller firm out in Katy, handling contracts for mid‑size construction companies instead of multinational corporations. He’ll be fine. Men like him always land somewhere soft.

Patricia, I’m told, joined a different country club. One that doesn’t use Rosa’s Commercial Services.

That’s all right.

We don’t need their money.

We have twenty‑five million reasons, and four hundred and twenty more, to know our worth.

And me?

I’m sixty‑two years old. I still have calluses on my hands. I still keep that first gray bucket by my back door, a reminder of everything we built when nobody was watching.

I’ll never forget the look on Christopher’s face in that ballroom when he told me to go to the kitchen, like my place in the world would always be behind a swinging door.

He was wrong.

My place is wherever I decide to stand.

If you’ve ever had someone tell you to know your place, pull up a chair next to me. Tell me where you’re reading this from. Because women like us, the ones with callused hands and straight backs, we’ve been sitting at the back tables for a long time.

We’re done asking permission to move forward.

Sometimes I think about the women who came before me.

My mother, who scrubbed other people’s laundry on a stone by the river back home. My grandmother, who sold tamales from a basket she carried on her head. None of them ever sat in a boardroom with men in suits offering them twenty‑five million dollars over coffee.

But all of them knew what I finally learned in that ballroom.

You don’t wait for someone to slide a chair over for you.

You stand up and pull out your own.

There was a time when I thought the only way to keep my family safe in this country was to keep my head down and my mouth shut. If I worked hard enough and stayed small enough, maybe nobody would notice us unless it was to say “thank you” and hand us a check.

Then a man with a Harvard ring told me to go to the kitchen.

And my daughter took off a three‑carat diamond in front of seventy people.

If that night taught me anything, it was this: silence is also a choice.

Have you ever sat at a table and pretended you didn’t hear what people really thought about you, just to keep the peace?

I did. For years.

I won’t do it again.

A few weeks after the meeting with the Wellington board, my operations manager, Carla, called me in a mild panic.

“We need to talk about staffing,” she said, leaning in my office doorway with a clipboard hugged to her chest. “If we’re taking on the expanded contract, Rosa, we can’t keep running the same skeleton crew on overnights. People are already giving up weekends. We’re at capacity.”

My office wasn’t fancy. Just a converted storage room at our small warehouse in southwest Houston with a metal desk, a couple of mismatched chairs, and a bulletin board crowded with schedules. On one wall, I’d taped a photo of our first van from 1987 faded paint, hand‑lettered logo right next to a current photo of our fleet lined up like white dominoes.

Both pictures mattered.

“How many more people do we need?” I asked.

“Realistically?” Carla flipped through her papers. “If we don’t want folks burning out, at least sixty more over the next few months. Maybe more once the new building wing opens. Turnover is killing us, Rosa. People leave for an extra dollar an hour and health insurance.”

She wasn’t accusing me. She was just telling the truth.

For years, I’d run the business like we were always one bad month away from collapse. Anyone who’s ever lived paycheck to paycheck knows that feeling doesn’t go away just because the numbers on the checks get bigger.

But the Wellington deal had changed our math.

Twenty‑five million dollars over ten years.

Four hundred and twenty employees who showed up in the dark to make sure other people’s spaces sparkled in the morning.

And a woman who had been told, to her face, that the work she built her life on made her less than.

Maybe it was time for my fear to loosen its grip.

“What if we stopped acting like we’re still that one‑bucket operation?” I asked Carla.

She blinked. “What do you mean?”

“I mean,” I said slowly, the idea forming as I spoke, “what if we start paying like the company we actually are? Better base pay. Real health insurance, not just the cheap plan with holes. Paid time off. Maybe a small retirement match.”

Carla stared at me like I’d suggested buying a private jet.

“Rosa, that’s… huge,” she said. “We’d be the unicorn in this industry.”

“Unicorns are just horses that kept walking,” I said. “We can afford it now. The Wellington contract alone covers a lot of that. And if we can’t afford to treat our people decently, what’s the point of all these zeros?”

She sat down slowly in the chair across from me.

“You’re serious,” she said.

“I’m sixty‑two,” I said. “If not now, when?”

She laughed, a quick, disbelieving sound.

“You know they’re going to cry in that break room, right?” she said. “In a good way.”

“Then we’ll buy more tissues,” I said.

That afternoon we called an all‑hands meeting.

We couldn’t fit everyone at once, not with four hundred and twenty people spread across shifts and sites, but word travels fast in any company. We held three sessions over two days: morning, afternoon, evening. Miguel stood against the back wall each time, arms folded, eyes bright.

I looked out over faces from every corner of Houston Black, Latino, Vietnamese, white, young, old, people with missing teeth and people with college degrees they couldn’t use and I thought about Patricia’s voice in that ballroom.

“Imagine if someone asks what Rosa does for a living.”

I cleared my throat.

“Most of you know I started this company with one bucket and one client,” I said. “For a long time, I ran things like we could lose that client any minute. Maybe some of you grew up like I did. You never sit all the way down because you’re waiting for somebody to tell you to move. You never take a deep breath because you’re waiting for bad news.”

A murmur of recognition moved through the room.

“I can’t promise you nothing bad will ever happen here,” I said. “But I can promise you this: as long as this company is mine, we will not build it on your fear.”

I told them about the new pay scale. About the health insurance plan we’d negotiated. About paid time off that didn’t require begging a supervisor. About a modest 401(k) match that would show up every paycheck like a quiet promise.

People did cry.

A man named Luis, who’d been with me since the early days, wiped his eyes with the back of his hand and said, “Nobody’s ever done this for us, jefa.”

“You’ve been doing it for me for years,” I said. “This is me catching up.”

Later that night, after the last group had drifted out and the warehouse was quiet again, I sat alone at my desk.

For the first time, the number four hundred and twenty felt less like a weight and more like a chorus.

If you’ve ever had to decide between staying small and finally believing the numbers in your bank account, you know that’s its own kind of courage.

The magazine article came out a month later.

The Wellington member publication was usually full of golf tournament scores and photos of women in pastel dresses holding wine glasses on the patio.

That month, the cover was a photo of the eighteenth hole at sunset.

But on page six, there I was.

“From Bucket to Boardroom,” the headline read, over a photo of me standing in front of our oldest work van, arms crossed, laughing at something the photographer had said.

The writer had spent an hour at my kitchen table asking questions while I made coffee: why we came to Houston, how the business grew, what it meant to me to employ four hundred and twenty people.

I kept waiting for her to ask about Patricia and Christopher.

She never did.

When the article mentioned the rehearsal dinner at all, it was just one line: “A recent incident at the club underscored the importance of treating all partners and guests with dignity.”

The focus was on my employees. On our overnight crews who never saw the sunlight on those golf greens. On the women who cleaned the locker rooms before the tennis ladies arrived.

“That’s the part they need to see,” I told Miguel, tapping the paragraph about Maria, who’d been promoted from night cleaner to site supervisor. “Not my face. Theirs.”

He nodded.

“It still feels good to see your face,” he said.

Isabella took a copy of the magazine to work.

She left it in the staff break room at the pharmacy without saying a word.

By lunchtime, her coworkers had read it.

“Your mom is a boss,” one of the techs told her.

“I know,” Isabella said, smiling.

That night, she came over for dinner and placed the magazine on our table between the tortillas and the salsa.

“Mama,” she said softly, tracing the headline with her fingertip. “When he laughed at you, I thought my life was ending. I thought I’d ruined everything.”

“You didn’t ruin anything,” I said. “You ripped off a bandage we should have never put on.”

She took a breath.

“If you could go back,” she asked, “to that moment in the ballroom before I walked back from the restroom and heard them would you still stand up when he told you to go to the kitchen?”

I didn’t answer right away.

In my mind, I saw Christopher’s face, the tilt of his head, the way the whole room watched.

“Yes,” I said finally. “Even if you hadn’t heard them at the bar. Even if you’d married him anyway. I would still stand up.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Because I have to live with myself in the mirror every morning,” I said. “Not with those seventy people. Not with Patricia. Not with Christopher.”

I looked at her.

“And because you were watching,” I added. “Even when you weren’t in the room yet, you were watching.”

Have you ever looked back at a moment and realized you weren’t just making a choice for yourself, but for whoever was watching you, quietly taking notes?

That realization will change the way you move your chair.

The extra money from the expanded contracts didn’t go just to benefits.

I’d spent my life watching smart, hardworking people stuck in jobs that chewed up their backs and knees because there was nowhere else to go.

I wanted something different for the next generation.

So one Saturday, with the Houston sun already turning the driveway into a griddle by ten a.m., I gathered Isabella, Miguel, and Carla around our kitchen table.

The gray bucket sat by the back door, now hosting a cheerful explosion of marigolds.

“I want to start a scholarship,” I said.

Isabella blinked. “A what?”

“A scholarship,” I repeated. “For the children of our employees. Trade school, community college, university whatever they qualify for. Books, fees, maybe a laptop. We start with five students next year. Then we see how far we can grow it.”

Carla’s mouth fell open.

“Rosa, that’s… huge,” she said again, just like she had in my office weeks earlier.

“Five kids,” Miguel mused, drumming his fingers on the table. “That’s at least fifty thousand dollars a year if we do it right.”

I nodded.

“Fifty thousand out of a company worth more than fifty million isn’t going to break us,” I said. “But it might change five lives.”

Isabella’s eyes filled with tears.

“Mama,” she whispered. “You’re really doing this?”

“We are,” I said. “And I want you to help vet the applications. You know what it’s like to write essays about your dreams and stare at tuition numbers that don’t make sense.”

She laughed wetly.

“I still have nightmares about FAFSA,” she said.

“Then you’ll be perfect,” I said.

We spent the rest of the afternoon sketching out guidelines on a yellow legal pad. Minimum GPA. Recommendation letters. A short essay about what dignity meant to them.

“That last one is yours,” Isabella said, nudging me. “The dignity question.”

“Maybe,” I said.

But the truth was, I wanted those kids to think about it long before the world tried to answer for them.

Have you ever met a young person who still thinks their worth is something they have to earn from other people? I have. I raised one. I used to be one.

It takes time to unlearn that lie.

Sometimes a check with your name on it helps.

The first scholarship ceremony was small.

We rented the fellowship hall at our church and set up folding chairs in uneven rows. Miguel and a couple of the guys from the warehouse rigged up a projector so we could show slides of the recipients’ photos.

I wore the same navy dress.

It had become my armor and my flag.

Five teenagers sat in the front row, flanked by parents in their good shoes. One girl, Yadira, wore the red polo shirt from the fast‑food place where she worked after school. Another boy, Jamal, had a tie so crooked I had to stop myself from getting up and fixing it.

When I stepped up to the front with the microphone, my hands trembled.

I’d faced country‑club boards and law‑firm partners.

Talking to these kids felt bigger.

“I’m not used to giving speeches,” I said. “I’m more comfortable with a mop than a microphone. But I wanted to say this to you myself.”

I told them about the bucket.

About the promises at the kitchen table.

About the night at the Wellington when a man tried to put me in my place and my daughter refused to let him.

“I built a business worth more than fifty million dollars with these hands,” I said, holding them up so they could see the calluses. “But that number is not why you’re sitting here today. You’re here because of your work. Your effort. Your late nights and early mornings. We’re just putting a little gas in your tank.”

Yadira wiped her eyes.

Jamal’s crooked tie started shaking along with his shoulders.

“If you ever find yourself at a table where someone treats you like you don’t belong,” I said, voice catching, “I want you to remember this moment. Remember that somewhere in Houston, there’s a woman who scrubbed toilets and signed paychecks and stood up in a room that wasn’t built for her and said ‘no.’ And then I want you to stand up, too, in whatever way is safe and right for you.”

Miguel watched me from the back, his eyes shining.

Afterward, as we took photos and handed out certificates, Yadira’s father came up to me.

He wore his work boots with his best shirt.

“Señora Rosa,” he said, his voice rough. “I was at the Wellington once. As a dishwasher. I know how those people look at us. Seeing you up there today…”

He trailed off, swallowing hard.

“Gracias,” he finished.

I squeezed his hand.

“De nada,” I said. “We’re just getting started.”

Time has a way of folding in on itself when you get older.

One minute you’re teaching your daughter how to hold a sponge without soaking her sleeves. The next you’re standing in a hospital room, watching her hold her own daughter, tears shining in her eyes.

Isabella and Daniel’s first child arrived on a rainy Tuesday in late October.

They named her Elena Rosa.

“Are you sure?” I asked, my throat tight when they told me.

“Yes,” Isabella said. “We’re sure.”

In the hospital room, while Daniel stepped out to call his parents, I sat in the uncomfortable vinyl chair and cradled my granddaughter.

She had a tuft of dark hair and a scowl that reminded me of Isabella’s newborn face.

“Hola, pequeña,” I whispered. “Welcome to Houston.”

I thought about the women in my family whose names no one had ever written in magazines. I thought about the boardrooms they never saw, the contracts they never signed.

I thought about the fact that this tiny girl would grow up in a world where her grandmother’s work had been mocked on a hot mic and then honored in print.

Both truths would be part of her story.

“I promise you this,” I murmured, rocking her gently. “No one is ever going to make you feel ashamed of where you come from. Not if I have anything to say about it.”

Have you ever held a child and felt the weight of every choice you’ve ever made settle on your shoulders like a blanket and a shield at the same time?

That’s what it felt like.

Miguel came back into the room with Daniel, grinning so wide his cheeks looked like they might split.

“Abuela Rosa,” he said, kissing the top of my head. “How does it feel?”

“Like we did something right,” I said.

Every now and then, someone asks me if I ever regret not keeping my head down that night.

“Wouldn’t it have been easier to just laugh and go to the kitchen?” a woman at church asked once, not unkindly. “Keep the peace for your daughter?”

“Easier for who?” I asked.

Because that’s the real question, isn’t it?

Easier for the people already comfortable.

Harder for the girl watching her mother decide whether she’s worth causing a scene for.

If you’re reading this and thinking about your own story, I want to ask you something gently: What would you have done at that rehearsal dinner? Sat still and swallowed the insult? Taken off the ring? Walked out with your parents? Or stood there frozen between all three?

All of those answers make sense.

Fear is heavy. So is love.

Sometimes the bravest thing isn’t marching out of a room.

Sometimes it’s staying in your own skin when someone is trying to peel it away.

I don’t know where Christopher is today.

I’ve heard things, the way you hear about people in a city like Houston. That he’s at a smaller firm on the west side, handling construction contracts. That he shows up at charity events alone now, standing in corners, scrolling his phone.

I don’t spend a lot of energy confirming any of it.

What I do know is that every time one of our vans pulls up in front of an office building, a country club, a clinic, or a school, someone inside gets to start their day in a clean space because of us.

We wipe away fingerprints and coffee stains and the crumbs of meetings nobody remembers.

We don’t wipe away people.

Patricia, I’m told, found another club. A place with a different set of standards. One that doesn’t use Rosa’s Commercial Services.

That’s fine.

We were never really on the same guest list.

If you’ve stayed with me all the way to this point, you know this story isn’t really about a country club or a law firm or even a man with a Harvard ring.

It’s about a bucket.

About four hundred and twenty paychecks.

About a twenty‑five‑million‑dollar contract.

About a daughter who took off a ring in front of seventy people and chose her parents instead of a last name.

It’s about drawing a line in a place where the floor has always been polished smooth to make people like me slip.

When I look back over it all the long days, the insults, the contracts, the scholarship ceremonies, the night my granddaughter was born certain moments flash brighter than others.

Maybe they do for you, too.

Was it the instant Christopher pointed at the kitchen and told me to go back where I “belonged”? Was it the sound of Isabella’s ring hitting that china plate? The sight of Miguel’s face when the board offered us twenty‑five million dollars because they finally understood we were partners, not help? Or was it something quieter, like the way Yadira’s father said “gracias” with his work boots still on at his daughter’s scholarship ceremony?

If you’re reading this on someone’s Facebook feed, in between photos of vacations and recipes, I’d love to know which moment landed in your chest and refused to move.

And if you feel like sharing one more thing, tell me this:

What was the first boundary you ever set with someone you loved, even though your voice shook?

Maybe it was walking out of a room.

Maybe it was staying seated and saying “no.”

Maybe it was deciding, quietly, that however other people decided to see you, your place from now on would be wherever you choose to stand.

That, more than any contract or dollar amount, is the inheritance I wanted to hand down.

To Isabella.

To Elena.

To anyone who has ever been told to go to the kitchen when all they were doing was trying to celebrate at the table.

We’re here now.

We’re staying.

And we’re not asking permission anymore.

News

While I was away, my daughter-in-law brought in contractors and turned my condo into “her project.” She tore up the floors and changed everything without asking for permission, then acted like I didn’t even have the right to say a word. I thought it was just plain disrespect, until a quiet phone call revealed the truth: the pregnancy story she’d been using to pressure the family had never been real. And by the next morning, a written notice was sent out, clear enough to reestablish boundaries and bring everything back into proper order.

While I was away, my daughter-in-law brought in contractors and turned my condo into “her project.” She tore up the…

At a luxury dinner, my husband mocked our marriage in front of his friends, tossing out, “She’s not on my level,” like it was just entertainment. The whole table laughed, assuming I’d swallow it to keep the peace. I simply smiled, met his eyes, and said clearly, “Then don’t wait a year. End it today.” I stood up and walked out of the restaurant. That night, a message from his best friend left me speechless.

At a luxury dinner, my husband mocked our marriage in front of his friends, tossing out, “She’s not on my…

My son went ahead and handled something involving my car without talking to me first, thinking I’d stay quiet and let it slide. I stayed calm, gathered the necessary paperwork, and carefully reviewed every detail until everything became clear. Then I set a boundary that was steady, but firm enough that he couldn’t ignore it. The next morning, while he was still showing off his new car, I took the keys, finished what needed to be done, and drove his car away, leaving him stunned.

My son went ahead and handled something involving my car without talking to me first, thinking I’d stay quiet and…

On the day the inheritance was divided, her father left his daughter nothing but a few withered potted plants, as if to say she wasn’t worth caring about. She quietly took them home, tended to them day after day, and turned that barren corner of the yard into a lush garden, then into a small farm and a steady, thriving livelihood that left everyone stunned. Years later, when everything had turned around, her brothers came looking for her, sincerely asking her to share the secret.

On the day the inheritance was divided, her father left his daughter nothing but a few withered potted plants, as…

The CEO had made jokes about my private life and openly questioned my ability in front of the entire company. But at the most important meeting, I showed up with nothing but a wrench, a symbol of my craft, and I let the results speak for themselves. I presented my work calmly. When the German investors saw with their own eyes what I could actually deliver, they suddenly stood up, applauded, and the whole situation flipped.

The CEO had been making jokes about my private life for weeks, the kind that sound casual until you realize…

Three successful older brothers had always looked down on their younger brother, who came from a farming background, treating him like someone who “didn’t belong” in their own family. But everything changed in just a few minutes at the lawyer’s office, when the will was opened and the attorney read a single short line. Those words made the entire room fall silent, and the three brothers suddenly realized they had been wrong for a very long time.

Three successful older siblings had spent so many years looking down on their youngest brother that the habit had hardened…

End of content

No more pages to load