“Say hi to the sharks,” my daughter-in-law whispered as she boxed me in against the yacht railing, while my son just stood there smiling.

They thought they could corner me and go after my three-billion-dollar fortune. But when they came home, I was already waiting, with a very special gift and a truth that left them speechless.

If you’re reading this, you probably understand why I don’t trust “family time” the way I used to, and why a perfectly normal Tuesday in Massachusetts can still make my stomach turn even now, even after everything that happened and everything that got “handled” the way people love to say when they don’t want to describe the mess.

My name is Margaret Harrison. I’m sixty-seven, Boston-born, Beacon Hill adjacent now, the kind of woman who knows every elevator chime in her building and every neighbor who judges your recycling bin like it’s a federal crime. I know which concierge will quietly accept a Christmas card and which one will act offended, like you tried to bribe the Constitution. I know which streetlights on Charles Street change faster than the rest. I can tell what season it is by the smell of the wind off the river, and I still, embarrassingly, still feel a little thrill when I hear the distant groan of Fenway on a summer night, like the whole city is humming to itself.

Since my husband Robert passed two years ago, my life has been quieter, too quiet, despite the headlines that love to use words like “billionaire widow,” like grief is some kind of accessory you can wear with pearls. They wrote about my “unshakable composure.” They wrote about my “steely poise.” Nobody wrote about me standing in the kitchen at midnight, staring at the coffee maker, forgetting which button made the light come on because the house felt wrong without his footsteps.

Robert wasn’t born into money. Neither was I. We built it the way people build anything in New England, stubbornly, brick by brick, with more work than glamour and more paperwork than anyone would believe. He used to say Boston rewards endurance the way the ocean rewards sailors, eventually, if you don’t panic. We did well. We did extremely well. We also did something that turned out to be naïve: we assumed the most dangerous people would always be strangers.

David is my only son, and he’s learned to sound affectionate in the same way corporate emails sound sincere. He can put warmth in his voice the way you put a filter on a photo. So when he called me himself, no assistant, no calendar invite, no “looping Vanessa in,” I felt that old, foolish warmth rise in my chest anyway, because mothers are ridiculous that way. Even wealthy ones. Especially wealthy ones, maybe, because money can’t buy you out of hope.

“Mom,” he said, and he stretched the word like he was pulling it from a safe place. “We want to toast your recovery from surgery.”

He paused, and I could almost hear him looking around whatever room he was in, checking that Vanessa was watching him do it right.

“Just the three of us,” he added. “Like a real family.”

Six weeks after a hip replacement, I was still counting steps and pretending I wasn’t lonely. I’d gotten good at making loneliness look like independence. I’d gotten good at saying, “Oh, I’m fine, I like the quiet,” with the same smile I used at charity dinners when somebody asked about Robert in that careful voice people use when they’re hoping you don’t cry on their napkin.

So I said yes. I said yes because the invitation felt like a rope thrown across a gap. I said yes because when your child invites you somewhere, some part of you still believes it’s love, even when you’ve seen the invoices.

I dressed carefully in a navy dress Robert used to compliment. He liked navy on me. He said it made my eyes look younger, which was sweet and also ridiculous, because at sixty-seven you don’t need anyone pretending you’re younger, you need someone telling you you’re still you. I pinned my hair the way I always did, the way I’ve done it since the eighties, neat and practical and not trying too hard. I slipped on sensible flats, because the surgeon had been clear and my body, for once, was giving orders. Then I rode a taxi down past the brownstones and the early commuters sliding onto I-93 with coffee cups and dead eyes, everyone moving like the day was a machine that only worked if you fed it your exhaustion.

Out the window I watched the city do what it always does, which is pretend it isn’t sentimental. Boston doesn’t do big feelings in public. Boston does efficiency. Boston does sarcasm. Boston does, “You’ll be fine.” Even the sky does it, that pale, hard blue that makes you feel like you should toughen up.

In the lobby of my building, the doorman held the door for me. He always did, but that morning his hand lingered, like he was making sure I didn’t wobble. I remember thinking, Look at you, Margaret. Healing. Showing up. Trying. And right behind that thought was a smaller one, nastier, one I didn’t want to admit: Don’t be stupid.

The marina smelled like salt, sunscreen, and money. There’s a particular scent to expensive marinas, not just ocean, but the layered smell of polished teak, expensive cologne, and new canvas covers, like even the boats are wearing designer. Somewhere a radio was playing something cheerful, some yacht-rock song that made the whole place feel like a commercial for a life that doesn’t include consequences.

David’s yacht was a glossy white forty-two-footer with chrome that caught the sun like a camera flash, the kind of boat you buy when you want the world to clap for your lifestyle. It was too much boat for Massachusetts waters in my opinion, too much “look at me,” but my son has always liked things that announce themselves.

David hugged me a beat too long, like he was performing for an invisible audience. His arms were strong, still, but his embrace was careful in a way that felt rehearsed. Vanessa watched from the deck with a smile sharp enough to cut crystal.

She was beautiful. I can say that. People always make it sound like you can’t say your daughter-in-law is beautiful if you don’t like her, but life isn’t a moral essay. Vanessa was tall and polished and the kind of pretty that looks expensive. Her hair fell in deliberate waves. Her sunglasses were the kind you see on billboards. She had the posture of someone who believes she belongs in every room she enters, which I used to admire until I learned what she did with that belief.

“Isn’t she beautiful?” David said, sweeping his arm like he was unveiling a new product launch.

He talked about taking it to the Caribbean. He talked about upgrades. He talked about “well-deserved luxury,” and all I could think was how familiar his confidence sounded. It was the same tone he used last year when I gave him three million dollars to “invest in his consulting firm,” money I’d started to suspect never touched a business account. He called it seed funding. He said the right words. He said “liquidity.” He said “strategy.” He said “growth.” He said “I’m building something, Mom.” And because I wanted to believe my son was building something other than excuses, I wrote the check.

For the first hour, they played sweet. Vanessa passed around mimosas like a hostess at a PTA brunch, bright and chirpy, and David made small talk about renovations to my old house, the one I’d signed over because grief makes you say yes to anything that sounds like “simpler.” They talked about the kitchen island like it was a miracle they’d rescued from my outdated taste. Vanessa mentioned “open concept” twice. David mentioned “resale value” like he was doing me a favor by living in the home I’d chosen with Robert when we still had more future than past.

The Massachusetts coastline shrank behind us. The water stayed calm. The sky was that clean, indifferent blue. I almost let myself believe the day would end with a toast and a hug that meant something, maybe a laugh that didn’t feel forced. I even caught myself watching David’s profile as he steered, remembering him at twelve, cheeks sunburned on Cape Cod, begging for another hour on the beach. Mothers collect those memories like seashells. You don’t realize how sharp they can be until you step on one.

Then David steered the conversation where he really wanted it.

My will. The trust.

“Probate is complicated, Mom,” he said, refilling my glass with a little too much enthusiasm.

He watched my face like he was looking for a flicker of confusion he could later label as proof. Vanessa lifted her phone, pretending it was just a casual selfie angle, but the lens kept finding me, my voice, my hands, the champagne, the words “trust” and “assets” floating out of my mouth. I know what it looks like when someone pretends not to record you. I lived through enough boardrooms to recognize a staged “casual.”

That’s when the cold truth slid into place. The “temporary” power-of-attorney papers they’d brought to the hospital. The way they insisted on “handling the paperwork” while I was still foggy from pain medication. The way my financial adviser stopped returning calls right after David started “helping.” The way David asked for passwords with a smile, like it was affectionate. The way Vanessa said, “It’s just so much easier if we streamline,” like my life was an inbox.

I set my glass down slowly and kept my voice even, the way you do when you’re talking to someone you suddenly realize might not be safe.

“David,” I said. “Take me back to shore. Now.”

His expression changed like a door shutting. Not slammed, not dramatic, just closed, quiet, final.

“I’m afraid that’s not going to happen, Mom,” he said.

Vanessa stepped closer, her tone pleasant in the way people sound right before they file a complaint.

“We have concerns about your memory,” she said, like she was reading from a script. “We have it documented.”

Out there, with no other boats in sight, the ocean suddenly felt less dangerous than the two people behind me. There’s a loneliness to open water that you can’t understand until you’re in it, and I don’t mean the romantic kind people post about. I mean the kind where you realize the world can’t hear you. The city can’t hear you. The dock can’t hear you. You could scream until your throat split and the only thing that would answer is the wind.

David pulled out a folder of papers. Sign here, initial there. Words about “protection” and “simplifying” and “for your own good.” It hit me with a clarity so sharp it almost calmed me: they hadn’t brought me out to celebrate my recovery. They’d brought me out to corner me.

My son was trying to trap me in a story where I was confused and he was responsible. My daughter-in-law was filming pieces of it like she was collecting receipts. It was a hostile takeover, except the company was me.

I didn’t scream. I didn’t beg. I just said no, and I meant it.

Vanessa moved behind me, close enough that I could smell her perfume over the salt air. It was sweet and heavy, the kind of scent meant to linger in a room after you’ve left, like a signature. Her mouth came near my ear, soft and almost playful, like we were sharing a joke at a cocktail party.

“Say hi to the sharks,” she whispered.

The shove was quick, clean, timed for the moment I shifted my weight. One second my fingers were on the rail, the next the world tilted, and cold air tore the breath from my lungs as the Atlantic rushed up to meet me. I remember the splash, the shock, the distant sound of my son’s voice turning performative again, and then the yacht’s engines rising like a decision.

And here’s the part that still makes me laugh in the dark, the part that comes up when I’m alone in my kitchen and the kettle starts to whistle and my mind drifts back there whether I want it to or not: they truly believed that was the end of me. They truly believed that by nightfall they’d be home, rehearsing grief, making calls, arranging paperwork, moving pieces on a board I’d never see again.

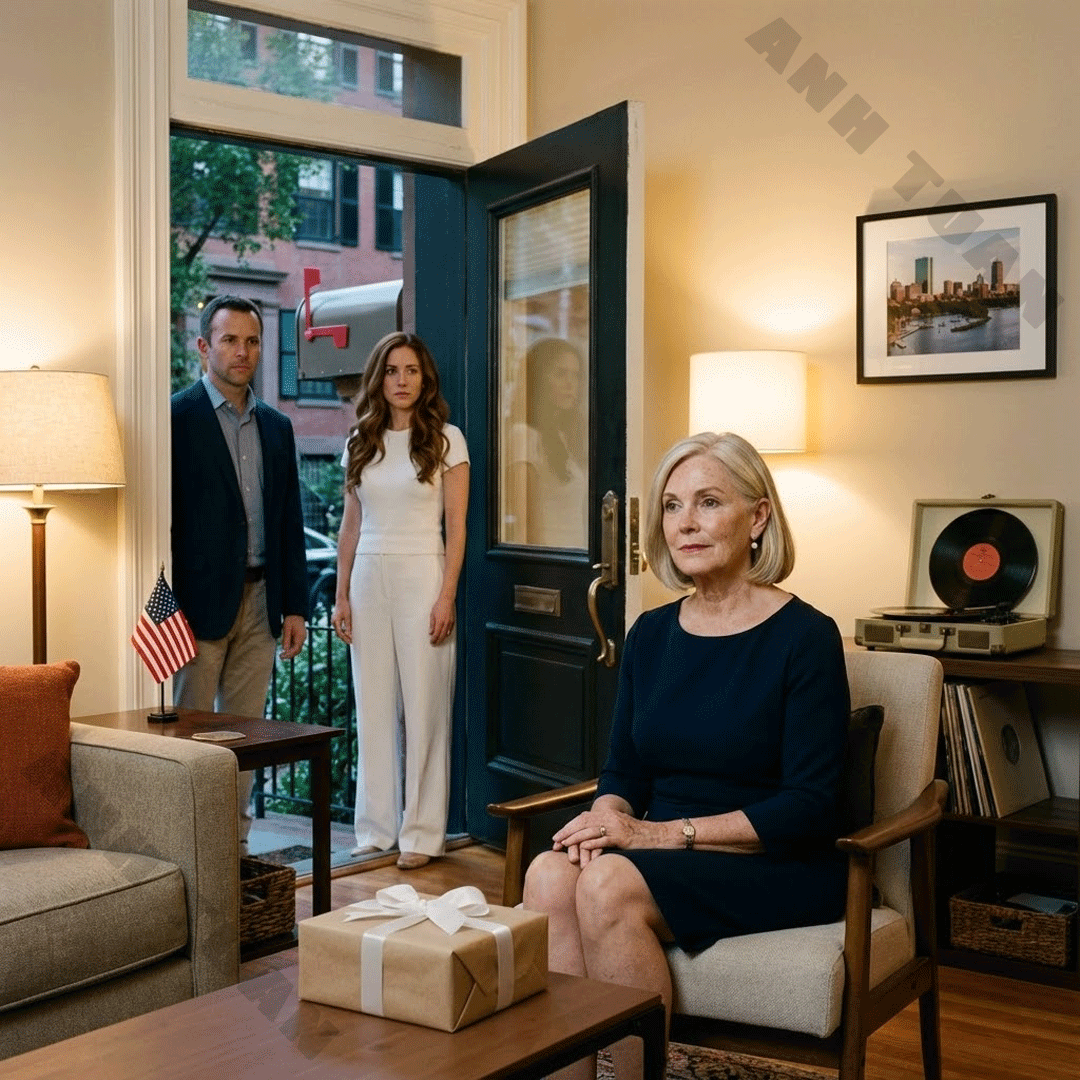

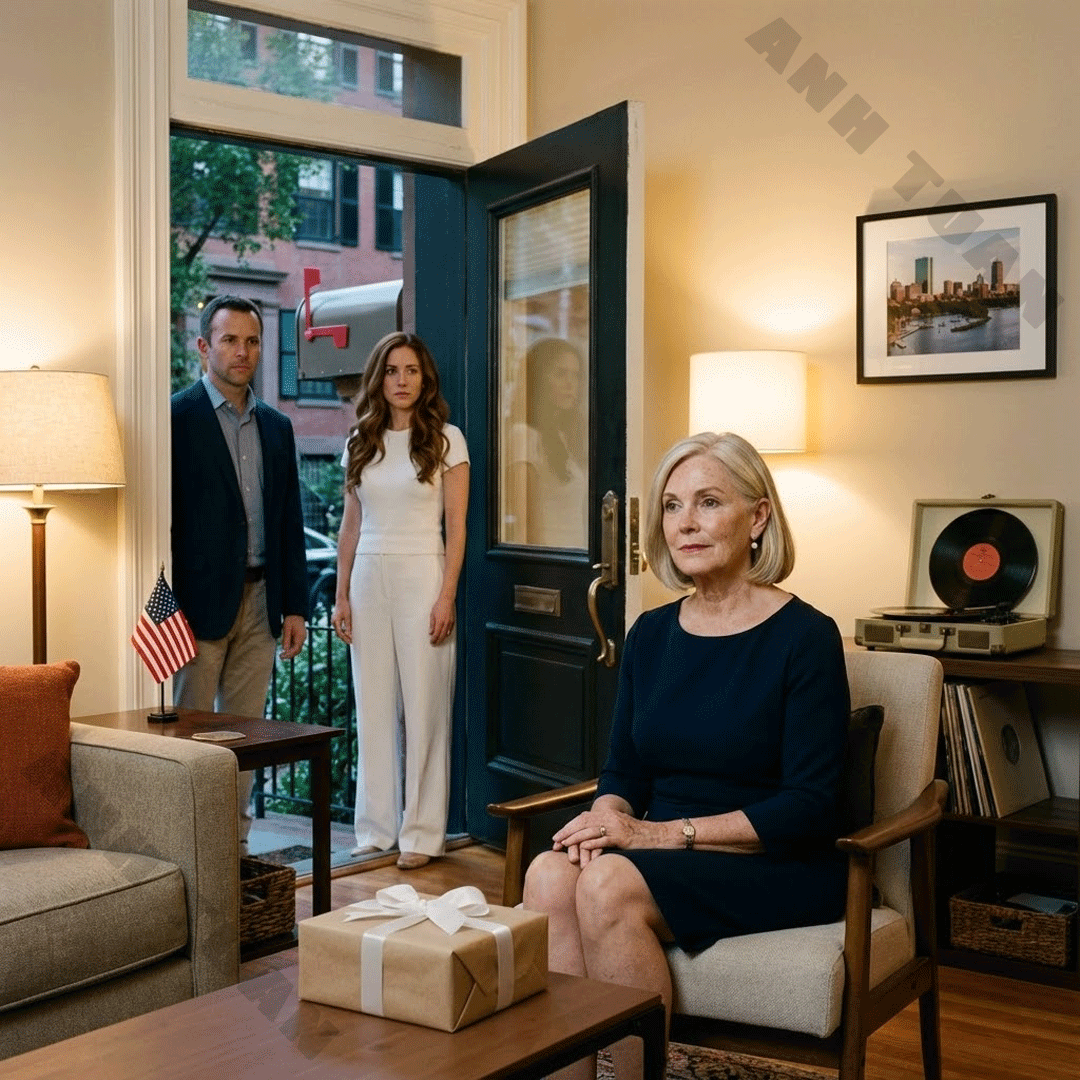

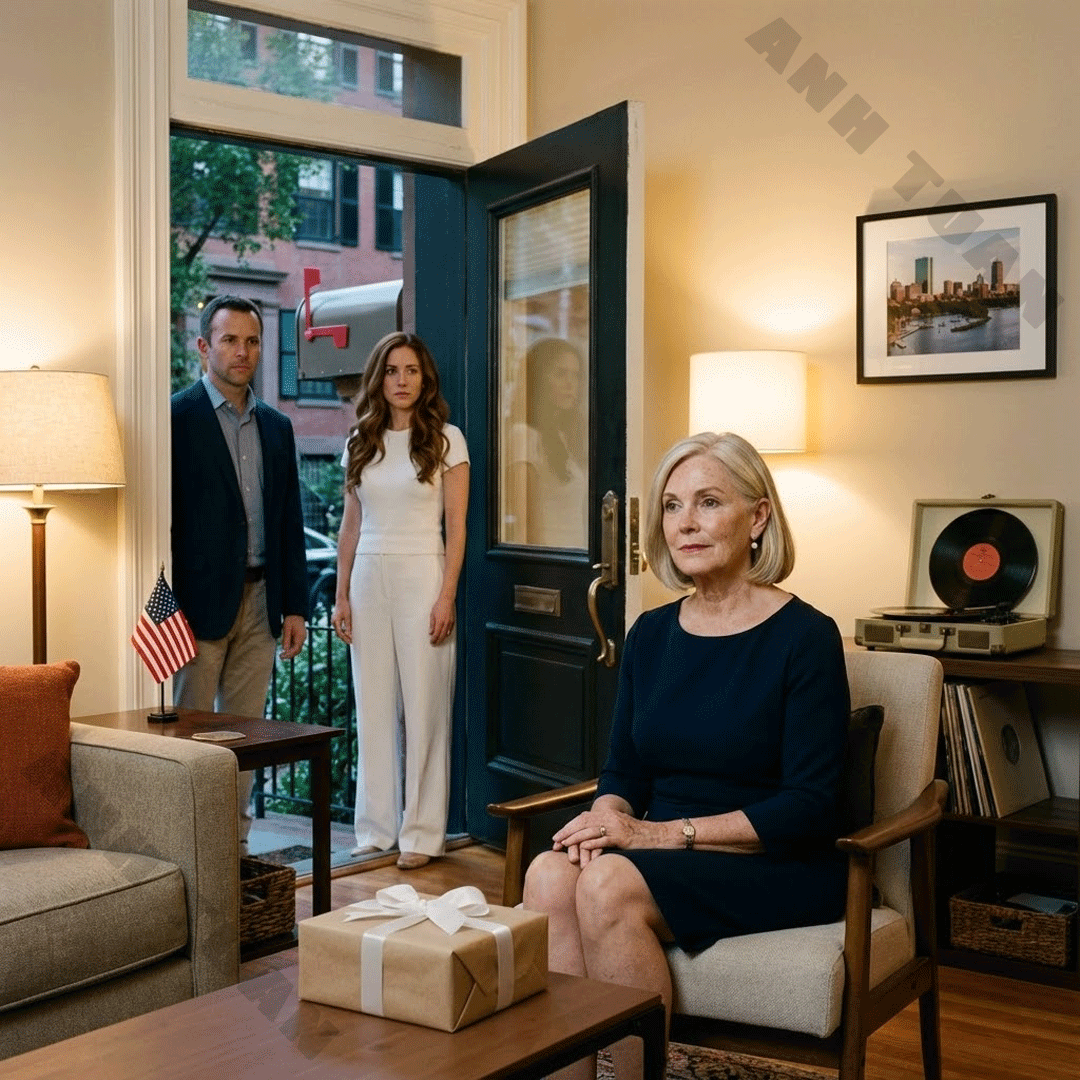

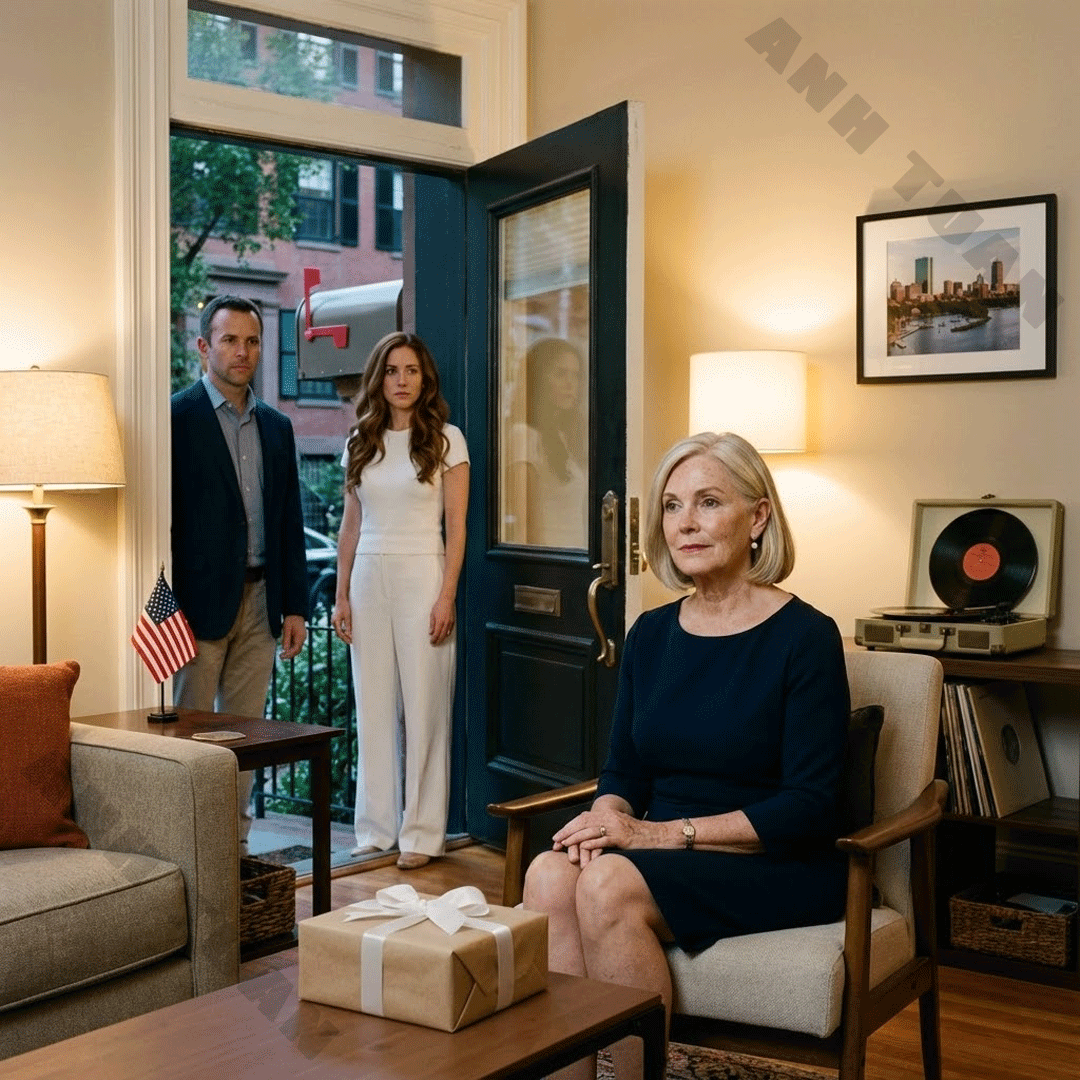

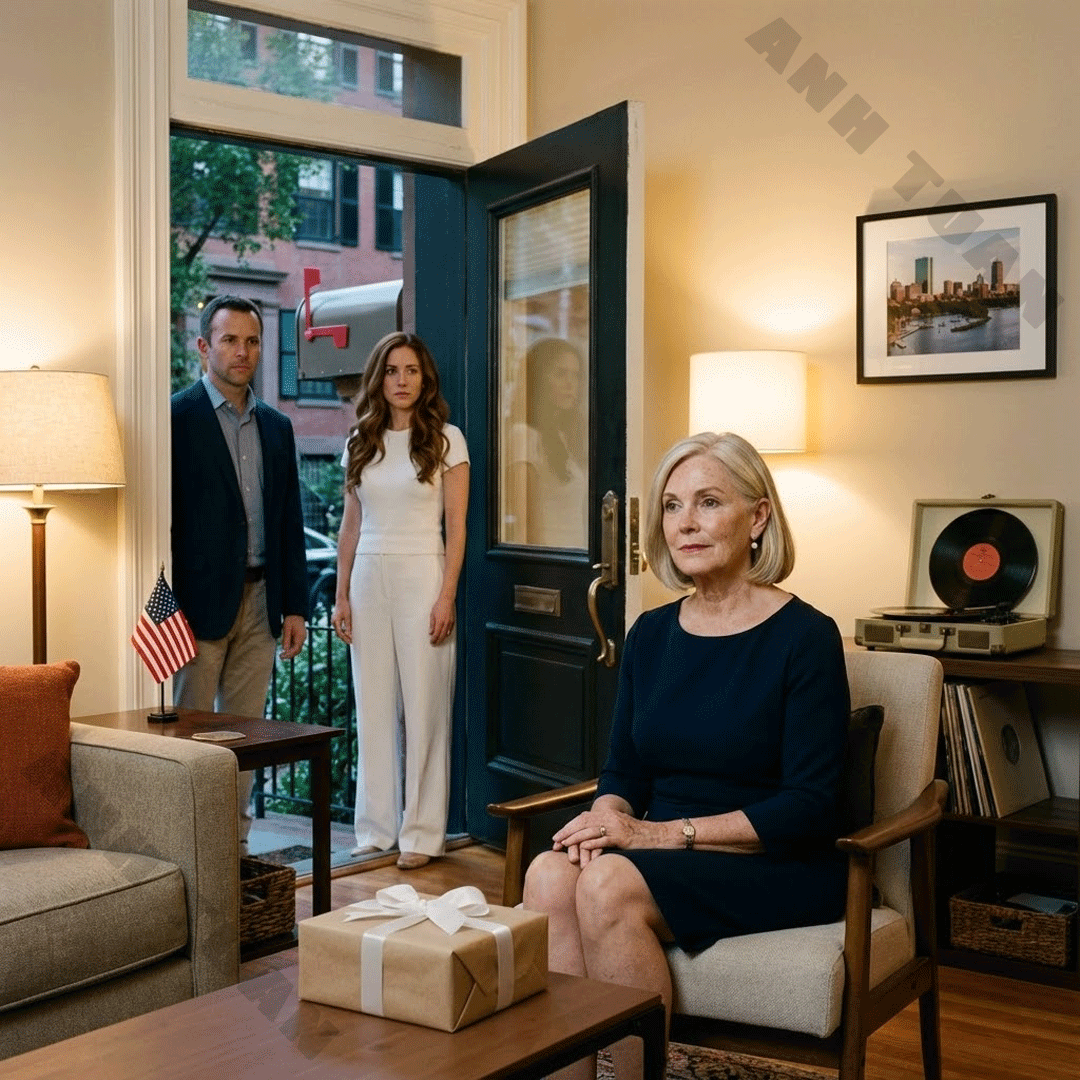

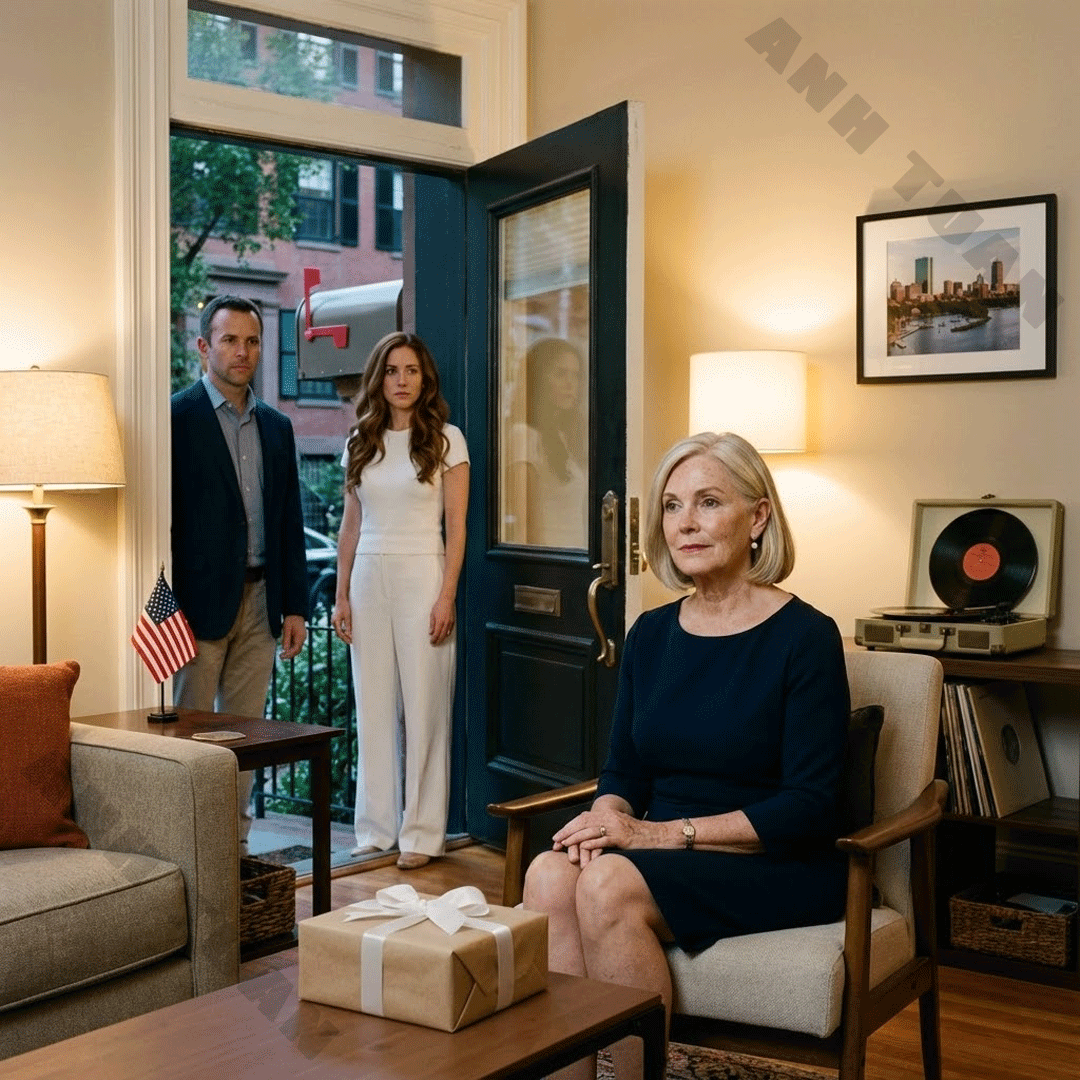

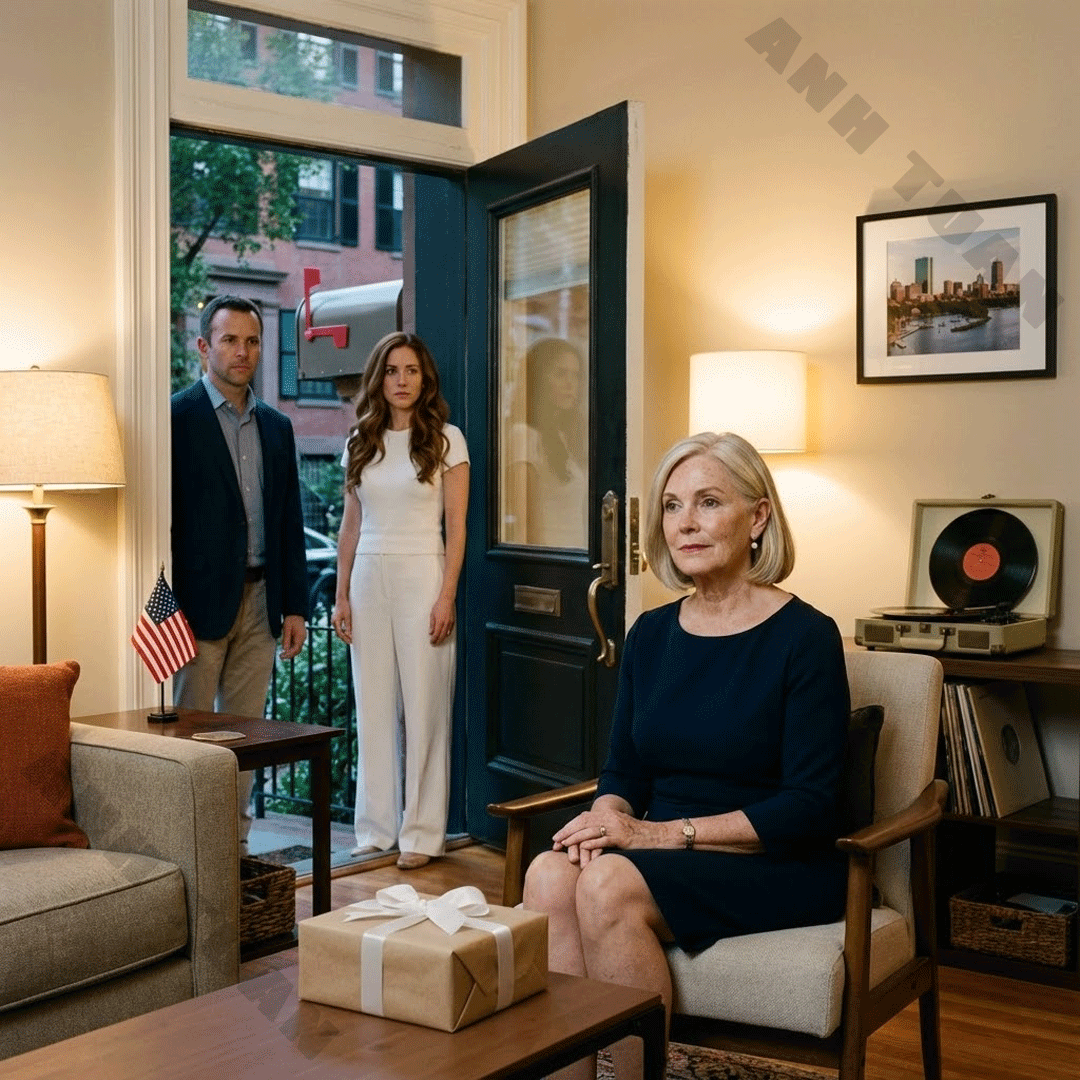

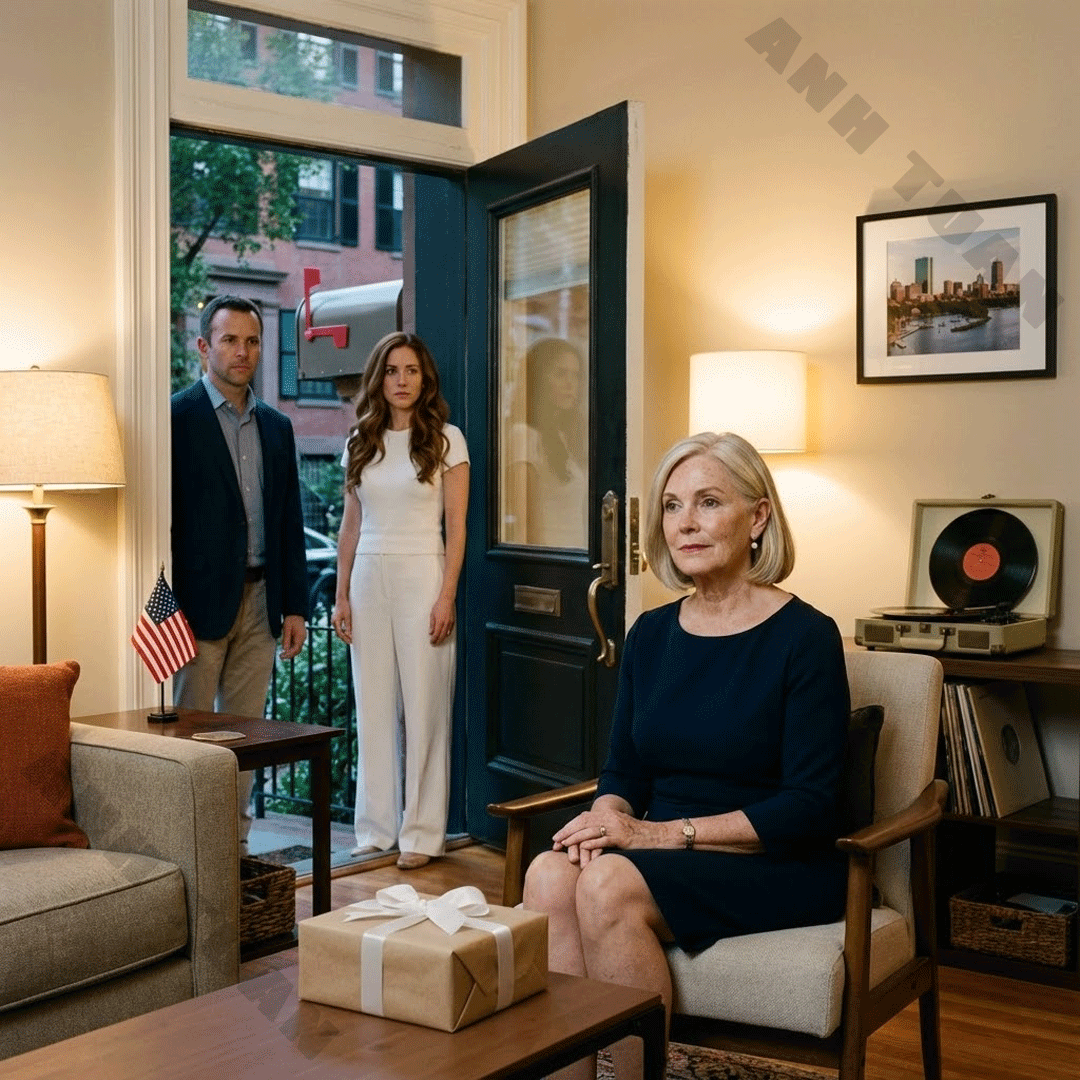

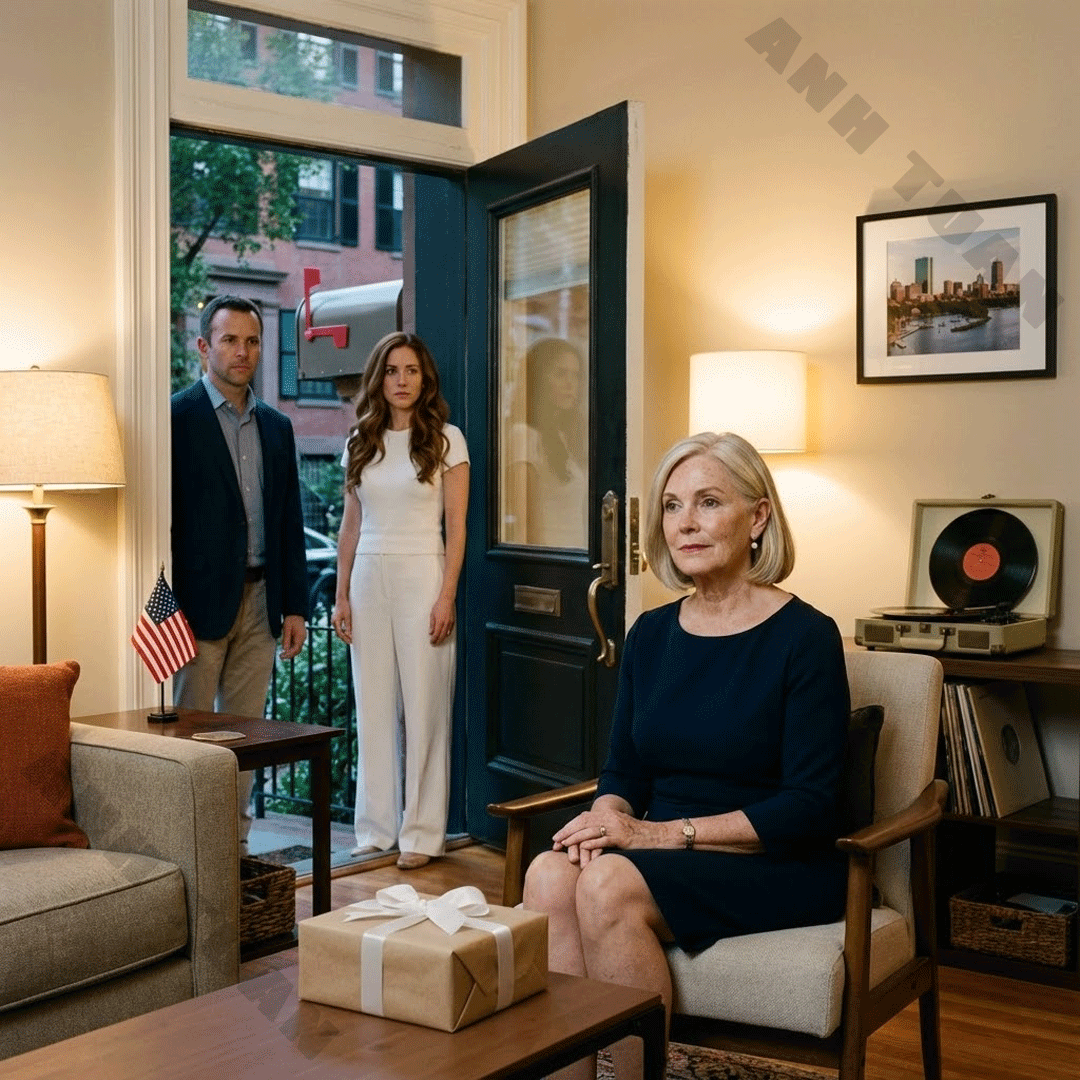

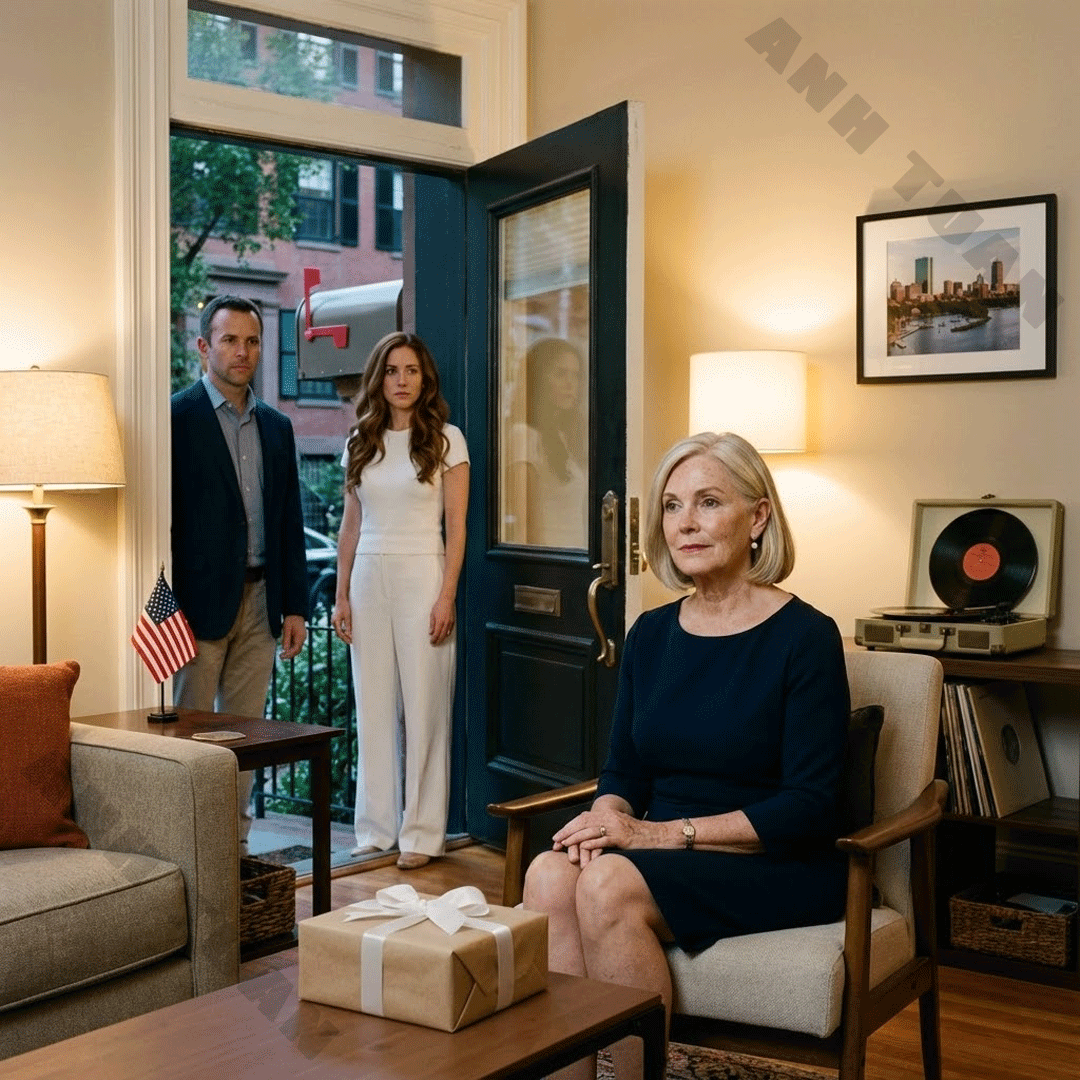

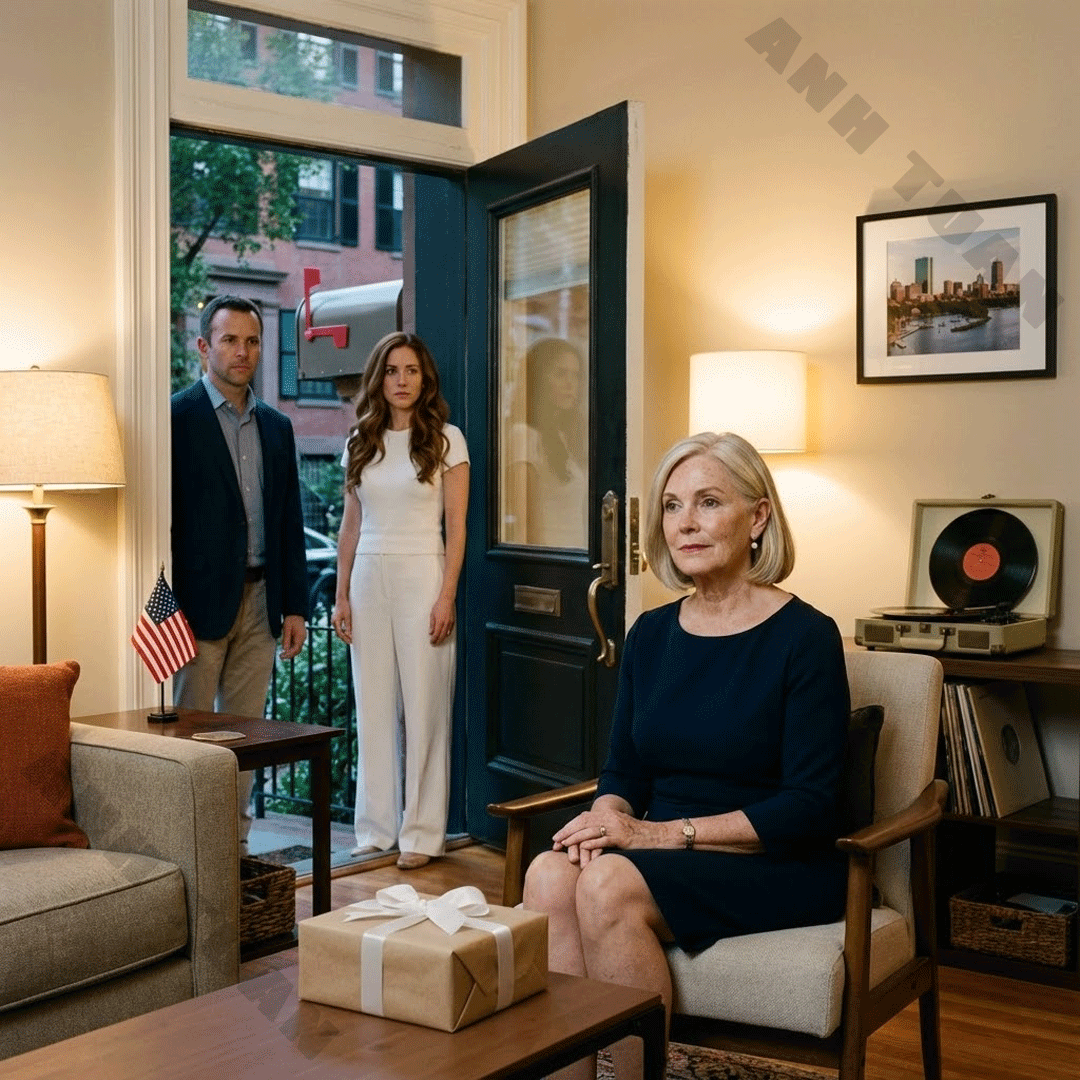

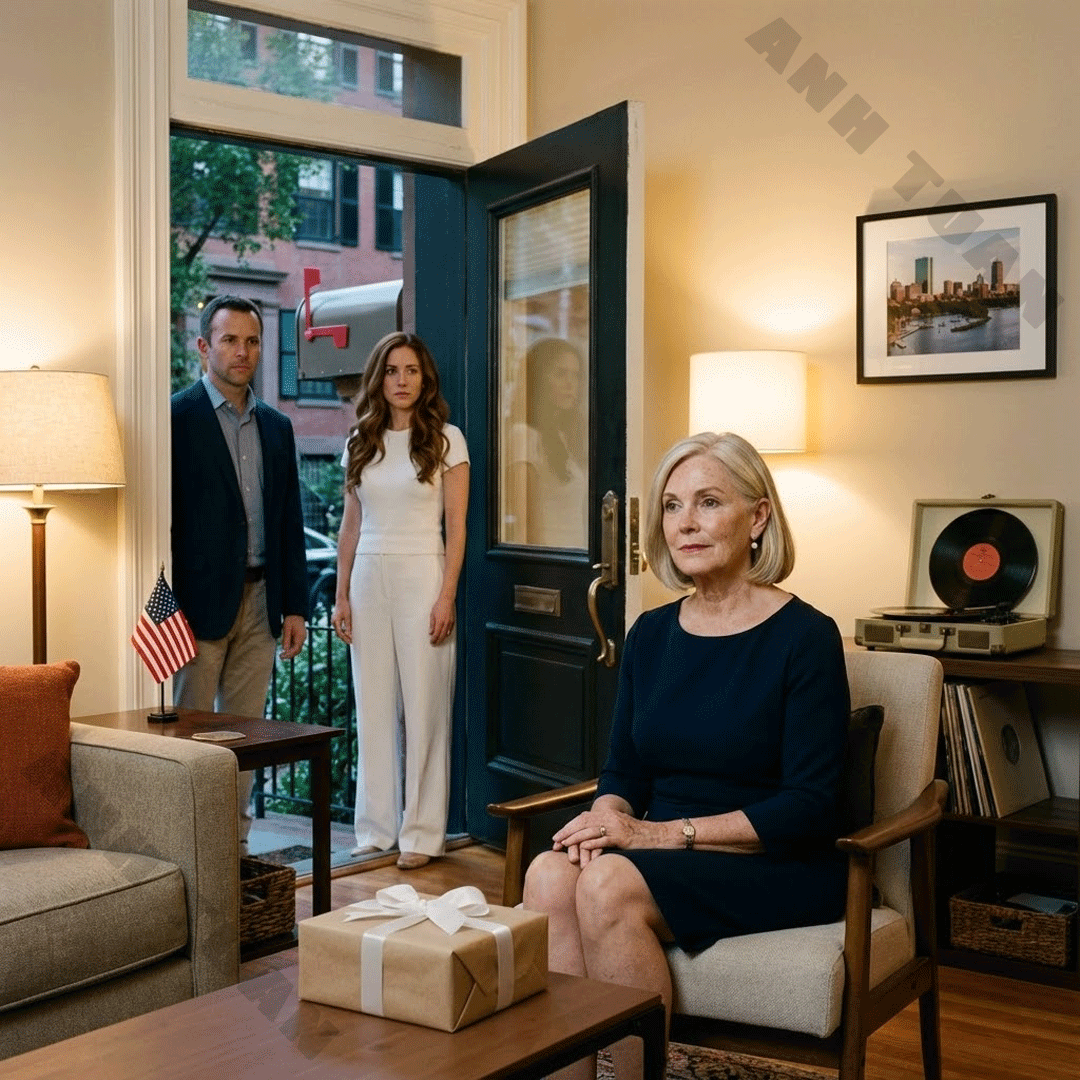

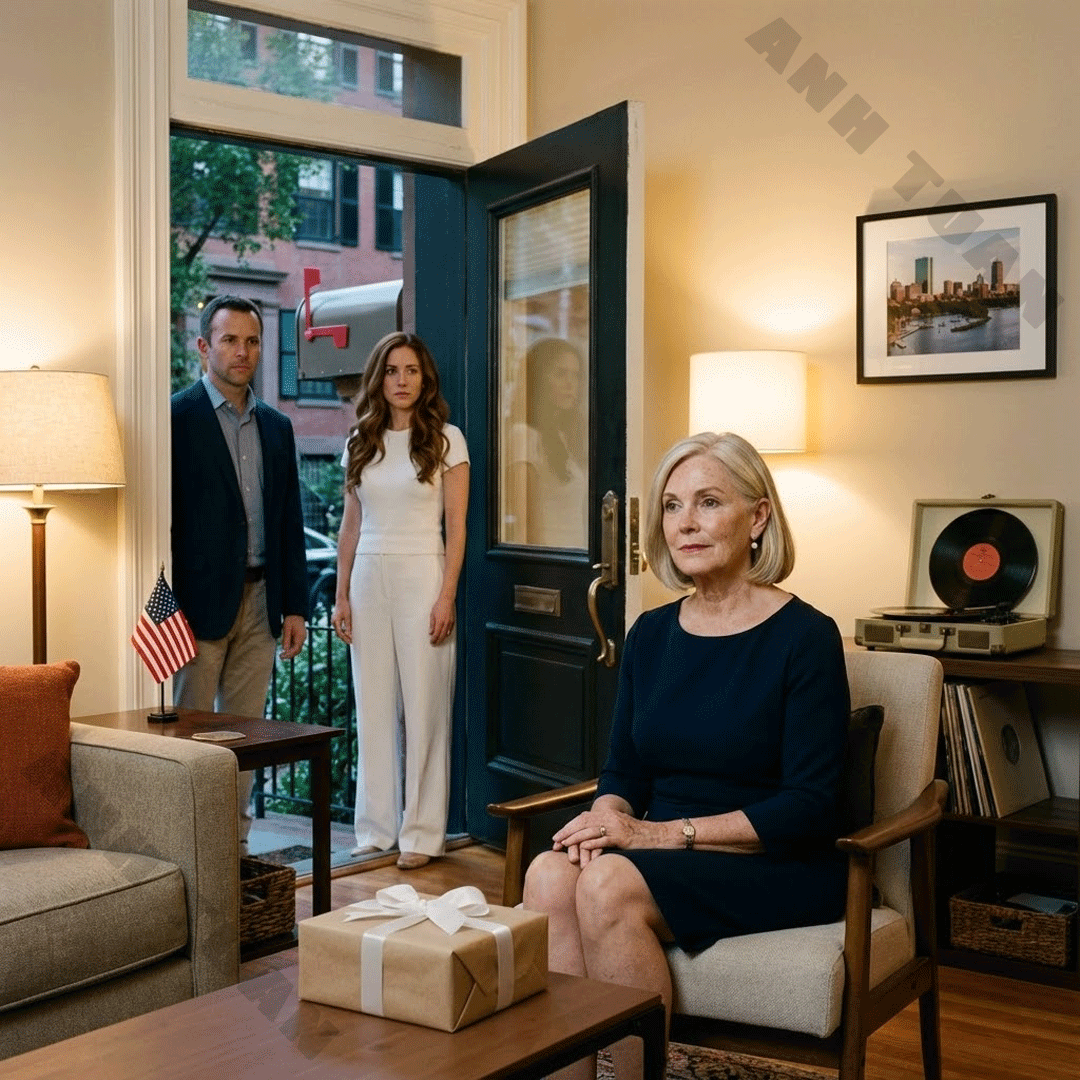

So when the front door finally opened later that evening, and David and Vanessa stepped inside expecting a quiet house and an easy next step, the first thing they saw was me. Dry. Still. Seated in my favorite armchair like I’d never left, with a neatly wrapped box on the coffee table between us.

Vanessa froze so hard I could practically hear her joints lock. David’s hand was still on the doorknob, like he didn’t believe what his eyes were telling him. I watched their faces do this little dance between disbelief and calculation, because that’s what people like them do when the world doesn’t follow their plan. They don’t feel. They adjust.

“Oh,” I said, because I didn’t know what else to say at first, and honestly, part of me wanted to see if my voice would shake. It didn’t. “You’re home.”

I should tell you now, before your imagination runs wild, that I did not become some kind of action hero in the Atlantic. I did not punch a shark. I did not swim ten miles to shore fueled by righteous anger and Pilates. I survived because of something much less cinematic and much more American: paperwork, planning, and the fact that I stopped trusting my own hope.

I need to rewind a little, because the truth is this wasn’t the first time David and Vanessa tried to put their hands on what wasn’t theirs. That yacht day was the loudest, the most dramatic, but the story began earlier, quieter, the way most betrayals do. They don’t arrive with a siren. They arrive with a smile and a “Let me help.”

After Robert died, I was surrounded by people. Lawyers, bankers, well-meaning friends, women from the charity boards who suddenly wanted to bring casseroles. Everyone spoke softly, like I was an animal that might bolt. In those first months, grief made me porous. I said yes to things I shouldn’t have. I signed documents without reading every line because my eyes kept blurring and I was tired of being strong.

David showed up more then. He was attentive in bursts. He’d call with that warm voice. He’d say, “Mom, I’m worried about you.” He’d show up with flowers that looked like he’d asked a concierge to pick “something nice.” Vanessa would sit beside him, hand on his knee like she was anchoring him, smiling at me like I was a sentimental photo she could tolerate.

At first, I was grateful. That’s the embarrassing part. I was grateful.

They offered to “handle the boring stuff.” They offered to “take things off my plate.” They offered to “organize my finances,” because Robert always handled that, and David said, “Dad would want me to look out for you.” I remember the way he said Dad. Like he was wearing Robert’s memory as a badge.

Then came the small changes. My mail started arriving opened, “by accident.” David started asking questions about accounts, about trusts, about “what happens when.” Vanessa started saying things like, “It’s just responsible to plan,” in that tone people use when they want to make you feel childish.

I had a financial adviser, a man named Peter Aldridge, who’d worked with Robert and me for twenty years. Peter was boring in the best way. Peter wore the same gray suits. Peter never used flashy words. Peter returned calls. Then one day, after David had been “helping” for a few weeks, I called Peter and got voicemail. Then again. Then again. When he finally returned my call, his voice sounded tight, careful.

“Margaret,” he said, “I was under the impression David was authorized to act on your behalf.”

My stomach did that slow drop you feel when an elevator starts descending and you weren’t ready.

“Under whose impression?” I asked.

There was a pause, and in that pause I heard fear, which is something you don’t expect from a man who manages money for a living. Money people are usually immune to fear. They fear market volatility. They don’t fear a widow’s son.

“I… received documentation,” Peter said.

“What documentation?” I asked, and my voice was sharper than I intended.

He hesitated, then said, “A temporary power of attorney.”

Temporary. That word. The way people use temporary as a blanket. Temporary bruises. Temporary confusion. Temporary authority. Temporary becomes permanent if you don’t fight.

I demanded copies. Peter sent them, and when I saw my signature, neat and familiar at the bottom, I felt my own skin go cold. I had signed it in the hospital, after the surgery, when the pain meds made the world feel slow and far away. I remembered David sitting at the edge of my bed, holding my hand, saying, “It’s just in case, Mom. Just to handle bills while you recover.” Vanessa had been there too, smiling, nodding, telling me it was “standard.”

Standard. Another word people use like a weapon.

I called David. I asked him directly what he was doing. He laughed, a little too quick, and said, “Mom, you’re overthinking. Vanessa and I are just trying to help. You were out of it, you know that.”

You were out of it. Those words landed on me like a hand on my mouth. Not concern. Control.

That night, I didn’t sleep. I sat in my living room with Robert’s old legal folders spread across the coffee table, the ones he kept because he never trusted anyone to “handle things.” He used to say, half joking, “The minute you stop paying attention, someone will decide your life belongs to them.” I used to roll my eyes and tell him he was paranoid. I wish I could apologize to his ghost.

By morning, I called my attorney, a woman named Ellen Cho who had the kind of calm voice that makes you feel like you can breathe again. Ellen had been Robert’s choice. She was sharp, meticulous, not easily charmed. She met me in her office downtown, in a building with views of the harbor that were so pretty they almost distracted you from the fact that you were talking about death and money.

Ellen listened while I explained, and she didn’t interrupt, which is how you know someone is actually competent. When I finished, she said, “Margaret, I need you to hear me clearly. There are people who weaponize caregiving. They use the language of help to gain access. It happens more than you think.”

I stared at the harbor, at the little boats moving like toys, and said, “My son wouldn’t.”

Ellen didn’t argue with me. She just let silence sit there until the truth had room to breathe.

“I want to revoke it,” I said finally.

“We can,” she said. “We also need to make sure your assets are protected, not just from strangers, but from anyone who could claim you’re incapacitated.”

Incapacitated. That word makes you feel like a door is closing on your autonomy.

Ellen asked me questions that felt personal and humiliating. Who has access to your medical information? Who has keys to your home? Who can impersonate you on the phone? Who knows your passwords? She asked me about Vanessa’s phone, about whether she posts on social media, whether she has a habit of recording. She asked me about David’s temper, his spending, his debts.

I didn’t want to answer. I answered anyway.

When we were done, Ellen said, “We can build a plan that creates checks and balances. We can make it very difficult for anyone to move money without multiple approvals. We can also create a situation where if someone tries, it triggers documentation.”

“Like a trap,” I said, and I heard how bitter I sounded.

Ellen’s expression didn’t change. “Like protection,” she said. “A trap is what they’re trying to do to you.”

That was when the story shifted, quietly, without fireworks. That was when I stopped being the grieving widow trying to keep the peace and started being a woman who understood she might have to defend her own life from her own family.

We did the paperwork. We revoked the hospital power of attorney. We issued formal notices to my banks and advisers. We moved certain liquid assets into accounts that required dual authorization, one from me and one from a trustee Ellen recommended, a man named Samuel Whitaker who used to work for a federal oversight office and had the personality of a locked safe. We updated the trust structure to include automatic auditing if any unusual activity occurred. We created medical directives that required independent evaluation, not just family testimony, if anyone ever tried to claim I was mentally unfit.

And then, because Ellen is the kind of woman who thinks three steps ahead, she said something that felt both insulting and lifesaving.

“Margaret,” she said, “I need you to assume they will escalate when they realize they can’t quietly take what they want.”

Escalate. Another word that makes your stomach tighten.

“How?” I asked, and my voice sounded small.

Ellen’s gaze was steady. “Financially first. Socially. Legally. They’ll try to isolate you. They’ll try to create a narrative that you’re unstable. They’ll bait you into reactions. They’ll record you. They’ll look for anything they can use.”

I thought of Vanessa’s phone. I thought of David’s practiced warmth. I thought of the way he’d said, You were out of it.

“I don’t want to believe my son could hurt me,” I said.

Ellen nodded once. “I know,” she said. “But your job isn’t to believe. Your job is to prepare.”

So I prepared.

Not in a dramatic way. Not in a “call the press” way. In the quiet way that women like me have always survived. I updated security at my building. I changed locks. I adjusted who could access my medical portals. I stopped signing anything without Ellen reviewing it. I told my staff, discreetly, that no one was to enter my home without my direct approval, not even David, not even Vanessa.

And then, because I’m human, I still made the mistake of craving normal. I still wanted my son to love me the way sons are supposed to. I still wanted a family that felt like warmth, not like a hostile negotiation.

That’s why, when David called about the yacht, some part of me heard the words and wanted to believe them. Recovery. Toast. Real family. My heart, traitor that it is, leaned toward that.

But my gut didn’t.

So I did something that feels embarrassing to admit, but I’m going to admit it because it’s the truth and because if you’ve ever been betrayed, you know how weird survival can look.

Before I got in that taxi, I called Ellen’s office. Ellen herself didn’t pick up, because she’s not the kind of lawyer who sits by the phone waiting for drama, but her assistant did.

“This is Margaret Harrison,” I said. “If I don’t call you by five o’clock, I want Ellen to know.”

There was a pause on the line, and the assistant’s voice shifted into seriousness. “Of course,” she said. “Where will you be?”

“I’m going on my son’s boat,” I said, and it felt ridiculous to say out loud, like I was tattling. “Just… note it. Please.”

Then, because I’d learned how people operate, I did something else. I turned on location sharing on my phone and sent it to Ellen. I also sent it to Samuel Whitaker, the trustee. I also sent it to my building’s head of security, a retired Marine named Frank who had the kind of face that always looks like it’s assessing threats.

I didn’t tell David I’d done any of that. I didn’t want to feel paranoid. I wanted to feel like a mother going to a toast.

I also wore something under that navy dress that I hadn’t worn in my life before. It was thin and discreet, the kind of inflatable safety vest sailors wear that sits flat until it hits water. Frank had suggested it, gently, like he was offering me an umbrella. He didn’t say, “Because your son might throw you off a boat.” He said, “Just in case. Water is unpredictable.”

I nodded like it was normal, because sometimes the only way to do a terrifying thing is to pretend it’s routine.

So when Vanessa shoved me, when the world tilted and the air left my lungs, when the Atlantic hit me like a slap from a god that doesn’t care about family drama, the vest did what it was designed to do. It inflated with a sudden, violent little burst that startled me as much as the water did. It yanked my body upward even as panic tried to drag me down.

I won’t romanticize what it felt like to hit that water. It was cold in a way that felt ancient. It stole my breath. It made my chest seize. For a moment my mind didn’t have room for betrayal, only survival, only the primal fact of lungs needing air.

I surfaced, coughing, and the sky above me looked huge and indifferent. The yacht was already moving away. David was at the helm. Vanessa was on the deck, a pale shape against the white of the boat. I heard something, maybe David shouting, maybe Vanessa laughing, maybe the wind playing tricks. I raised my arm, not even to wave, just instinct, the way you lift your hand when you’re drowning and you want the universe to notice.

Then the yacht’s engines rose, and the boat angled away like it had somewhere better to be.

There are seconds in life where time becomes thick. That was one of them. I floated, held up by that vest, and I watched my son leave. I watched him choose the story where I disappeared. I watched the distance grow between us, and something inside me shifted so quietly I almost missed it.

It wasn’t rage. Not at first. It was clarity, like a fog lifting. It was the understanding that whatever love I’d been trying to salvage, whatever family fantasy I’d been feeding, was already dead. All that was left was the shape of it, and the shape could be used against me.

The water carried me. The vest kept my face above the surface. My body shook. My hip screamed with a pain that made my vision blur, and I thought, not poetically, just practically, I cannot die like this. Not because of them. Not because my son and his wife decided my life was an inconvenience.

Then, because preparation is not glamorous but it works, my phone did the other thing I’d set it to do.

It pinged a geofenced alert when it got wet, because Samuel Whitaker had helped me set it up. I’d felt absurd doing it, like I was starring in my own paranoid thriller, but Samuel had said, “It’s not paranoia if you’ve got evidence of attempted manipulation.” He didn’t say attempted murder. None of us said that word. Saying it would have made it too real.

The alert went to Ellen. It went to Samuel. It went to Frank.

And because Frank is Frank, he called the Coast Guard.

I didn’t know any of this while I was out there. I only knew water and cold and the strange, hollow sound of my own breath. I only knew I had to stay calm, because panic wastes oxygen. I only knew that if I started thinking about sharks, I would lose my mind.

Do you know what your brain does when someone whispers “sharks” in your ear and then you’re floating alone in the Atlantic? It offers you every horror movie you’ve ever half watched. It offers you teeth. It offers you shadows under the surface. It offers you the sensation of every small bump against your leg as a possible death.

I kept my legs still. I kept my hands on the vest. I stared at the horizon and told myself things like, You are in Massachusetts. Sharks are not a guaranteed death sentence. People surf. People swim. People live. I told myself it like a mantra, because sometimes the only way to survive is to lie to your fear until your fear gets tired.

Minutes passed, maybe ten, maybe twenty. Time was a smear. My hip throbbed. My hands went numb. The sun that had felt so pretty on the deck became cruel, glaring off the water. I kept thinking about Robert, not in a sentimental way, but in flashes. His hand on my back when we walked. His quiet patience when David was a teenager and slammed doors. His voice, calm, saying, “Watch the details, Maggie. The details never lie.”

Then, finally, I heard it. A low thrum at first, distant, then growing. I looked up and saw a helicopter, small against the sky, moving toward me with a steadiness that felt like mercy.

I started to cry then, not sobbing, not dramatic, just tears leaking out because my body was too tired to hold them in. I raised my arm again. The helicopter angled. A voice crackled from somewhere, and then the sound of the world shifted as the rotor wash hit the water, whipping it into white.

A rescuer dropped down, a man in bright gear, moving like he’d done this a thousand times. He reached me, grabbed me, clipped me in. He spoke into my ear, and I couldn’t hear the words, but the tone was firm, calm, practiced, the tone of someone who doesn’t need you to be brave because he’s bringing enough bravery for both of you.

They lifted me. The water fell away. The yacht was gone. The coastline was a thin line. The sky was still indifferent, but the helicopter was not.

On land, it became a blur of lights and blankets and questions. An EMT kept asking my name, my date of birth, the president’s name, like he was testing whether I existed. I answered. Margaret Harrison. Nineteen fifty-eight. I won’t tell you which president I named because politics makes everything uglier, and this story is ugly enough.

They brought me to a hospital, not the one where I’d had surgery, but one closer to the coast. They checked my hip. They checked my lungs. They asked me what happened, and I stared at the ceiling and tried to decide which version of truth would keep me alive.

Because here’s the thing nobody tells you: when someone hurts you, especially when it’s family, the first danger isn’t always the injury. Sometimes the first danger is the narrative. If David and Vanessa got ahead of the story, they could paint me as confused, as unstable, as dramatic, as a woman who fell because she’s old and stubborn. They could turn my survival into my own fault.

So I said, carefully, “I was pushed.”

The nurse’s eyes widened, but she didn’t react theatrically. She asked, “By whom?”

“My son’s wife,” I said, and my mouth tasted like metal.

A doctor came in. Then another person, someone with a badge. Then Frank arrived, his face grim, and behind him Ellen, hair still perfectly arranged like she’d stepped out of a courtroom, not a crisis.

Ellen took my hand and said, “We’re going to do this properly.”

Properly. That word saved me.

They took a statement. They documented bruising. They documented saltwater in my lungs. They documented the fact that my safety vest had inflated, which was a detail that made the officer’s eyebrows lift, like he was thinking, This woman knew.

And then Ellen did what Ellen does. She made calls. She set things in motion. She told me, “You are not going home yet.”

“I want to go home,” I whispered, and I hated how small I sounded.

Ellen’s voice was gentle, but her eyes were steel. “Not yet,” she said. “They will go to your house. They will expect you to be gone. They may try to enter. They may try to take documents. They may try to establish control. We need to be ahead of them.”

“How?” I asked.

Ellen glanced at Frank, then back at me. “By letting them think they succeeded,” she said.

That sentence landed like a stone in my chest.

I am not a woman who enjoys games. I like clear rules. I like contracts. I like people who do what they say. But I understood, in that moment, that my life had become a game whether I wanted it to or not. David and Vanessa had already started playing. If I refused to play back, I would lose by default.

So Ellen laid out a plan that was both horrifying and, in a cold way, elegant.

Frank would coordinate with my building security. They would let David and Vanessa in if they arrived, because denial could escalate things, and because we wanted to see what they did. Cameras would record everything. The concierge would act normal. Frank would have plainclothes security nearby. The police would be notified but not visible, unless needed.

Meanwhile, Ellen would arrange for me to be transported home quietly, not through the lobby, but through a service entrance. My building had one, because Beacon Hill buildings always have layers, old money architecture stacked like secrets. I would be brought up to my unit without David and Vanessa seeing me arrive.

Then I would wait.

I hated it. I hated the idea of sitting in my own home like bait. I hated the fact that my heart still wanted to believe David would walk in and collapse at my feet and say, “Mom, I’m sorry, I lost my mind.” I hated the part of me that was still a mother even after my son tried to erase me.

But I did it.

They wrapped me in blankets, gave me dry clothes, checked my vitals one more time, and then Frank drove me in an unmarked car back to Boston. The city lights blurred past the windows. People were out in restaurants, laughing, living, ordering oysters and arguing about parking like the world wasn’t full of sons who push their mothers into the sea. I watched them and felt like I’d slipped into an alternate reality, one where normal life was a costume you wore.

At my building, we didn’t use the front entrance. We went through the back, past the dumpsters and the delivery bays, past a door that smelled faintly of bleach and old brick. The elevator there had a different chime, lower, less polished. It felt like entering my own life through the wrong door.

In my apartment, everything looked the same. Robert’s framed photograph on the shelf. The throw blanket folded over the arm of the couch. The faint scent of lemon cleaner from the housekeeper’s visit the day before. It was so normal that it made my throat tighten.

Ellen arrived minutes later, carrying a folder so thick it looked like a weapon. Samuel Whitaker arrived too, calm as a bank vault, and behind him Frank, who positioned himself by the window like a silent guard.

“Sit,” Ellen said, and for once I obeyed without arguing.

She placed the neatly wrapped box on the coffee table. It was medium sized, wrapped in simple paper, no ribbon, the kind of package you’d bring to a birthday party if you didn’t want attention. It looked absurdly harmless.

“What is that?” I asked.

Ellen’s lips pressed together. “A gift,” she said. “For them. And for you.”

Samuel added, “It’s symbolic. And practical.”

I stared at it, and a bitter laugh tried to climb out of my chest. “I don’t feel like I’m in a mood for symbolism,” I said.

Ellen’s gaze softened. “You don’t have to be,” she said. “You just have to get through what comes next.”

So I sat in my favorite armchair, the one Robert used to tease me about because it was “too upright,” and I waited. My body ached. My hip throbbed. My hands still felt cold in a way that made me think the Atlantic had left a fingerprint on my bones. I held a mug of tea that I couldn’t taste. I watched the door like it might bite.

Hours passed. The sun lowered. The light in the room shifted from afternoon gold to dusk gray. Outside, the city moved on, because the city always moves on. Somewhere a siren wailed and faded. Somewhere a neighbor’s dog barked. Somewhere a delivery truck backed up with that beeping sound that feels like the soundtrack of modern life.

I thought about Robert. I thought about David as a child. I thought about the first time David lied to me, small and ridiculous, about a broken lamp. I thought about the way I’d scolded him, the way he’d cried, the way I’d hugged him and said, “You can always tell me the truth.” I felt something in me crack quietly at the memory of my own certainty.

And then, finally, the sound came. Keys. Voices in the hallway. Laughter, light and careless, like they were coming home from a party.

My stomach tightened so hard I thought I might be sick.

The lock turned. The door opened.

David and Vanessa stepped inside expecting a quiet house and an easy next step, and the first thing they saw was me. Dry. Still. Seated in my favorite armchair like I’d never left, with a neatly wrapped box on the coffee table between us.

For a second, it was almost funny, the way their bodies stopped mid-motion, like someone had paused a video. Vanessa’s smile slid off her face in a way that revealed the hard structure underneath. David’s eyes widened, then narrowed, then widened again, like his brain couldn’t pick a story and commit.

“Mom?” David said, and his voice tried to sound shocked, but it came out flat, like he’d forgotten how to perform surprise.

Vanessa’s hand went to her throat. “How…?” she started, then stopped, because if she finished that sentence, she’d have to admit there was a plan and it failed.

I looked at my son. I looked at the woman who had whispered about sharks like it was a joke. I felt grief, not just for what they’d done, but for who they were, because the worst part is realizing you didn’t lose them in that moment, you lost them long before, and you just didn’t notice.

“I had a long day,” I said, because my mouth still wanted normal words, because my mind was still trying to protect itself from the full horror of saying, You tried to kill me.

David took a step forward, then stopped, like he sensed a line on the floor he shouldn’t cross. His eyes flicked around the room, quick, searching. He noticed the box. He noticed the extra folder on the side table. He noticed Frank in the corner, quiet as a shadow. He noticed Samuel, standing near the fireplace like he belonged there.

Vanessa noticed too, and her posture shifted. She lifted her chin. That polished confidence returned, the one she wore like armor.

“What is this?” she asked, and her tone was sharp now, the sweetness gone. “Why are these people here?”

David’s voice changed. Softer. “Mom, are you okay?” he said, and I almost admired the audacity. “We were worried. You fell… you slipped, right? The water, it was ”

“No,” I said, calmly, and that one word felt like stepping onto solid ground. “I didn’t slip.”

The air in the room tightened. Outside, a car horn honked in the distance like the city didn’t care.

Vanessa’s eyes flashed. “Margaret,” she said, and hearing her say my name like that, without warmth, without pretense, made my skin crawl. “You’re confused. You’ve been confused. We’ve been trying to ”

“Save me?” I asked.

I kept my voice mild, almost conversational, because Ellen had warned me. Don’t give them drama. Don’t give them sound bites. Don’t give them a version of you that looks unstable.

David swallowed. “Mom,” he said, and now his voice had that corporate sincerity again, the one that always used to work on me. “Let’s just talk. We can figure this out. We don’t need… strangers.”

Samuel’s voice cut through the room, calm, polite. “I’m not a stranger,” he said. “I’m the independent trustee.”

David blinked. “The what?”

Ellen stepped forward then, and in that moment the room shifted, because Ellen carries authority the way some people carry perfume. “Margaret has updated her legal structures,” she said. “In ways you were not informed of, because you are not entitled to be informed of them.”

Vanessa’s mouth tightened. “That’s ridiculous,” she snapped. “We’re family.”

The word family sounded like a claim, not a feeling.

I leaned forward slightly in my chair. My hip protested. I ignored it. “Family doesn’t do what you did,” I said, quietly.

David’s face went pale. “What are you talking about?”

I held his gaze. “You left me out there,” I said. “You turned the boat around and you left.”

For a second, David looked like a little boy caught with his hand in a cookie jar. Then the mask snapped back on.

“Mom, you’re not thinking clearly,” he said, too fast. “You were drinking. You got dizzy. You fell. Vanessa tried to ”

Vanessa cut in immediately. “We tried to help you,” she said, voice rising, and I saw the panic under her polish now. “You refused. You got hysterical. You leaned over the railing, and we couldn’t ”

“Stop,” Ellen said, and her tone had the weight of a courtroom. “There are recordings. There are logs. There is medical documentation. There is Coast Guard documentation.”

David’s eyes flicked to the side. “Recordings?” he echoed.

Ellen nodded. “Yes,” she said. “Also, the building has cameras. And I would advise you to be careful about the story you tell next, because it will be compared against evidence.”

Vanessa’s face flushed. “This is insane,” she hissed. “She’s manipulating you. She’s ”

“She’s alive,” Frank said from the corner, finally speaking, and his voice was flat, unimpressed. “That should probably matter to you.”

David’s jaw clenched. He looked at me like he was trying to decide whether anger or charm would work better. He chose charm, because that’s his habit.

“Mom,” he said, stepping forward again, palms open, like he was approaching a frightened animal. “Whatever happened, I’m sorry you felt scared. But we can fix this. We can keep this private. We can handle it as a family.”

Handle it. The word made something in me harden.

I nodded slowly. “We are handling it,” I said. “Just not the way you planned.”

I gestured to the box on the coffee table. It sat there, innocent, almost pretty in the lamplight.

“That’s for you,” I said.

Vanessa’s eyes narrowed. “What is it?”

David hesitated, then reached for it like a man who can’t help himself. He picked it up, turned it in his hands, looking for clues. The paper was simple, the tape neat. His fingers trembled slightly, and I wondered if he was remembering the water, if any part of him had felt the cold truth of what he’d done.

“Open it,” Ellen said, because Ellen enjoys clarity.

David swallowed and tore the paper.

Inside was another box, plain, unmarked. He opened that too.

His face shifted as he saw what was inside, and for the first time that day, his performance slipped into something real.

It was a stack of documents, clipped and labeled, but on top, right where his eyes would land first, was something small and unmistakable: a keycard.

My building’s keycard. Mine, not his.

And attached to it, a single printed notice: ACCESS REVOKED.

Vanessa made a sound like a laugh that died halfway. “What is this?” she demanded, sharp and panicked.

Samuel spoke, calm as a metronome. “It means neither of you has legal access to this residence,” he said. “It means your key fobs have been deactivated. It means you are here without permission.”

David’s mouth opened, then closed. “Mom, come on,” he said, and now there was irritation, because charm had failed. “You can’t do this.”

I looked at him, really looked at him. “I can,” I said. “And I did.”

Vanessa’s voice went icy. “You’re going to throw your own son out?” she asked.

I didn’t answer her. I addressed David, because despite everything, it still felt important to speak to him directly, like he was still the child I raised, not the man who left me floating in the ocean.

“David,” I said, softly, “you tried to make me disappear.”

His eyes flashed. “That’s not what happened.”

I nodded once. “Then tell me what happened,” I said. “Look at me and tell me.”

He stared, jaw tight. His gaze flicked to Vanessa, and in that flick I saw the truth: he needed her approval. He needed her story. He needed the narrative they’d built together, because without it he’d have to face himself.

Vanessa stepped closer to him. “We don’t have to explain anything,” she snapped. “She’s unstable. That’s the whole point. That’s what we’ve been saying.”

Ellen’s voice was quiet but lethal. “You’ve been saying it,” she corrected. “And now you’ll have to prove it.”

Vanessa’s eyes widened. “Prove it to who?”

Ellen held up a finger, like she was counting. “To the court, if you attempt guardianship. To the police, if you deny an assault. To the insurance companies, if you file claims. To the financial institutions, if you try to move funds you are no longer authorized to touch.”

David’s face went white again. “Funds?” he whispered.

Samuel stepped forward. “There was an attempted transfer from Margaret’s primary trust account two weeks ago,” he said. “It was flagged. It was blocked. The request originated from a device associated with your office.”

David’s eyes snapped up. “That’s ”

Samuel didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to. “We have logs,” he said. “We have timestamps. We have the IP trail. This is not speculative.”

Vanessa’s lips parted. “You’re spying on us,” she said, and she tried to sound offended, but it came out frightened.

“No,” I said. “I’m protecting myself.”

David’s shoulders sagged slightly, like the weight of consequences was finally settling on him. “Mom,” he said, and his voice cracked, just a little. “You don’t understand. We needed ”

“We,” I repeated, and something in me almost laughed again. “You needed.”

Vanessa hissed, “Don’t start.”

David’s gaze flicked to her again, and that was the moment I truly understood what I’d been refusing to see. This wasn’t just my son being greedy. This was my son being weak. This was my son being led by his hunger and his fear and whatever emptiness he’d been hiding behind those corporate emails.

I took a slow breath. The room smelled like tea and paper and the faint expensive perfume Vanessa wore like a weapon.

“I’m going to tell you the truth,” I said, and my voice stayed calm, because calm is power, and I had learned that the hard way. “Not the story you’ve been telling yourselves, not the one you planned to tell everyone else. The truth.”

David’s eyes widened slightly, like he was bracing.

“The truth is, Robert and I planned for this,” I said. “Not for a yacht, not for… theatrics. But for the possibility that someone close to us might try to take control. Robert believed people reveal themselves under pressure. He believed money makes pressure inevitable.”

Vanessa scoffed, but it sounded weak now. “That’s convenient.”

I ignored her. “When Robert died, the trust structure had protections,” I continued. “Protections I didn’t fully understand because Robert handled the details. I regret that. But I’m learning them now, and Ellen is helping me, and Samuel is ensuring they’re enforced.”

David’s mouth tightened. “You’re punishing me,” he said, and the entitlement in his voice was so familiar it made my stomach twist.

“No,” I said. “I’m stopping you.”

I leaned back slightly, because my body needed it, then I said the sentence that, in a strange way, felt like setting down something heavy I’d been carrying.

“You do not have access to my money anymore,” I said. “Not directly. Not indirectly. Not through paperwork you tricked me into signing while I was drugged. Not through a story about my memory. Not through Vanessa’s phone recordings. Not through threats. Not through anything.”

Vanessa’s face twisted. “You can’t cut him off,” she snapped. “He’s your son.”

I looked at her then, really looked at her. “You pushed me into the Atlantic,” I said, and my voice was still calm, but the words were sharp. “Don’t talk to me about motherhood.”

Silence fell. David swallowed hard. Vanessa’s nostrils flared.

Ellen spoke then, because she is practical even when emotions are boiling. “You need to leave,” she said. “Now.”

David’s eyes darted. “No,” he said, and there was anger now, hot and desperate. “This is insane. Mom, you’re making a mistake. You’re letting them turn you against us. Vanessa and I have done everything for you.”

Everything. The word was almost funny.

Frank stepped forward slightly, enough to remind David that this was not a room he controlled. “Leave,” Frank said again, and his tone made it clear he was not asking.

Vanessa grabbed David’s arm. “We should go,” she hissed, but her eyes were still on me, burning. “This isn’t over.”

I nodded slowly. “It is,” I said. “It’s just not the ending you wanted.”

David’s face contorted, and for a moment I saw something raw there, something like fear. “Mom,” he whispered. “Please.”

That word, please, might have moved me once. It might have cracked me. It might have brought the mother in me rushing forward to comfort him, to fix it, to pretend.

But then I remembered the water. I remembered the engines rising. I remembered the distance widening. I remembered the way he chose to leave.

“I loved you,” I said softly, and that sentence hurt more than anything else I’d said. “I still love the child you were. But I don’t trust the man you are.”

Vanessa made a sound of disgust. “Oh, spare me,” she snapped, and the mask was fully off now. “You rich women love a moral speech. You don’t care about him. You care about control.”

I smiled then, small and tired. “Control?” I echoed. “You mean like taking me out to sea and trying to force me to sign documents?”

Her face went pale, and she looked away, because even she understood what she’d done was indefensible when spoken plainly.

Ellen stepped aside and motioned toward the door. “Now,” she said.

David hesitated, then turned. Vanessa pulled him. They moved toward the door, stiff, angry, humiliated. At the threshold, David stopped and looked back at me.

“This will ruin us,” he said, voice tight.

I held his gaze. “You ruined yourselves,” I said quietly. “I’m just refusing to disappear.”

They left. The door closed. The click of the lock sounded louder than it should have, like punctuation.

For a moment, I didn’t move. My hands were resting on the arms of the chair. My body was exhausted. My mind was still trying to catch up to what had happened, to the fact that my son had walked out of my apartment like a stranger.

Ellen exhaled. Samuel said something low to Frank. Frank checked his phone. Life kept moving, even in the aftermath of something that felt like an earthquake.

Ellen crouched beside me. “Are you okay?” she asked, and now her voice was human, not legal.

I stared at the empty space where David had stood and felt something in me unravel.

“No,” I admitted. “But I will be.”

That night, after they were gone, after the adrenaline drained and the apartment returned to its quiet, I sat with Ellen and Samuel and went through the rest of the box.

Because the keycard was only the top layer, the symbolic piece meant to land like a slap. Under it were copies of filings, notices, revocations, formal letters to banks and advisers, and something else, something that made my chest feel both lighter and heavier at the same time: a letter from Robert.

Robert had written it before he died. He’d sealed it with Ellen. He’d left it for me “if things get complicated,” which I’d assumed meant taxes or estate drama. I’d never imagined it would mean our son.

I opened it with hands that trembled, not from cold now, but from grief.

My dear Maggie, it began, and just seeing his handwriting made my throat tighten.

He wrote about love. He wrote about how proud he was of the life we built. He wrote about David, about how he hoped David would find his own strength, not borrowed strength, not performative strength. He wrote, gently, that David had always wanted the applause more than the work.

He wrote one line that I still carry like a stone in my pocket: If anyone ever tries to make you smaller to make themselves bigger, don’t negotiate. Protect yourself. You are not an asset. You are my wife.

I cried then, quietly, into my own hands, because Robert wasn’t there to hold me, and because even in death he had known, he had seen the edges of what I refused to see, and he had tried to leave me a map.

In the weeks that followed, the story unfolded the way stories like this always do, not in one dramatic scene, but in a hundred smaller ones.

David and Vanessa tried to call. I didn’t answer. They left voicemails that swung between sweetness and fury. David said he loved me. Vanessa said I was cruel. David said I was confused. Vanessa said I was selfish. Their voices sounded like a couple arguing over who gets the better script.

They tried to show up at the building again. Security refused them. Vanessa made a scene in the lobby, loud enough that a neighbor’s door cracked open upstairs. Boston buildings are quiet, but they also have ears. News travels through elevator chimes.

They tried to contact my doctors. Ellen had already locked that down. They tried to contact my old adviser. Samuel had already documented everything. They tried to make vague threats about legal action, about “concerns,” about “elder abuse” in reverse, as if I was abusing my grown son by refusing to bankroll him.

Ellen met every attempt with paperwork. Calm, relentless, American paperwork. Cease and desist. Formal notices. Documentation. The language of boundaries.

And here’s the part that surprised me: the more they tried to twist the story, the clearer the truth became to everyone else. People aren’t as gullible as manipulators hope. Nurses know what coercion looks like. Coast Guard personnel know what panic looks like. Lawyers know what lies look like. Even neighbors, even those Beacon Hill women who judge recycling bins like it’s a sport, can smell something rotten under perfume.

Still, it wasn’t clean. It wasn’t tidy. There were days I woke up furious, shaking with adrenaline, replaying the shove, replaying David’s face as he turned the boat away. There were nights I lay in bed and felt my chest tighten with the thought, My own son wanted me gone. There were mornings I made coffee and forgot to drink it because grief and rage are both thirsty things.

Sometimes I missed him in the stupidest ways. I’d see a kid on the street with David’s haircut from when he was ten. I’d hear someone laugh like him. I’d catch myself wanting to call him about something mundane, like a new restaurant in the North End, because my brain still had old habits.

Then I’d remember.

And then I’d feel something else: relief.

Because once you stop lying to yourself, the world gets sharper, but it also gets simpler. You stop negotiating with illusions. You stop sacrificing your safety for the idea of peace.

One afternoon, about a month after the yacht, Ellen invited me to her office again. She sat me down and said, “Margaret, we need to talk about what you want next.”

“What I want?” I repeated, and the question felt strange, like I’d forgotten I was allowed to want.

Ellen nodded. “You can pursue charges,” she said. “You can pursue civil action. You can keep everything quiet and focus on protection. But you need to decide what outcome you’re aiming for, because otherwise you’ll just react forever.”

React forever. That sounded like drowning in a different way.

I stared out her window at the harbor again. Boats moved on the water, small, calm. The world looked deceptively peaceful.

“What would you do?” I asked her, and I hated that I was asking.

Ellen didn’t answer right away. She studied me, like she was reading not just my words but my exhaustion. Then she said, “If it were me, I’d make sure they can never do this to you again, and I’d make sure they can’t do it to someone else either.”

Someone else. I hadn’t thought about that. I’d been so wrapped in my own shock, my own betrayal, that I hadn’t considered the possibility that David and Vanessa weren’t a one-time disaster. People who can do this once can do it again. Maybe not with me, if I was protected, but with someone else, someone less resourced, someone without Ellen and Frank and Samuel.

The thought made my stomach twist.

So we did both.

We pursued the legal protections, the financial safeguards, the documentation. We also pursued consequences, carefully, with evidence, with proper channels, with no drama. Ellen made sure every step was clean, because she understood what people like Vanessa rely on: the hope that you’ll get emotional and messy so they can call you unstable.

I didn’t give them that. I cried in private. I shook in private. I screamed into a pillow once, which felt humiliating and also necessary. But in public, in legal rooms, in official statements, I was calm. I was precise. I was unshakeable, not because I’m a superhero, but because I was tired of being prey.

David’s marriage began to crack under the pressure. That’s what I heard, anyway, through the quiet grapevine of people who know people. Vanessa blamed David for hesitating, for not finishing the job, for letting me survive. David blamed Vanessa for pushing too far, for turning a “plan” into a crime that even his denial couldn’t soften. Their alliance, built on greed, didn’t have the spine for real consequence.

When David finally requested a meeting, months later, through Ellen, not directly, I surprised myself by agreeing.

Not because I wanted reconciliation. Not because I wanted to play mother and son again like nothing happened. I agreed because I needed to see him, to look at his face and confirm, once and for all, that I wasn’t imagining it, that I wasn’t exaggerating, that I wasn’t being “confused.”

We met in a neutral place, a quiet conference room in Ellen’s building. David arrived alone. He looked older than he had on the yacht, as if the weight of reality had pressed down on his skin. His hair was slightly unkempt. His expensive suit looked like it had slept in a chair.

He sat across from me, hands clasped tightly, like he was trying to hold himself together.

“Mom,” he said, and his voice was smaller now.

I didn’t answer right away. I studied him. I looked for the child I remembered. I looked for the son I’d loved. I found only echoes.

“Why?” I asked finally.

David swallowed. His eyes flicked toward Ellen, who sat beside me, quiet. Then back to me.

“I didn’t think it would go that far,” he said, and the sentence was so pathetic, so cowardly, that for a moment I almost laughed. Not because it was funny, but because it was exactly what a man says when he wants to avoid the full shape of his own choices.

“You were going to let me die,” I said, flatly.

He flinched. “No,” he whispered.

“Yes,” I said. “You left. You didn’t call for help. You didn’t turn back. You didn’t do anything except drive away.”

David’s jaw worked. “Vanessa ” he started.

“Don’t,” I said, and my voice cut through the room like a blade. “Don’t put this on her. She pushed. You left. You are responsible for your part.”

He looked down, and when he spoke again his voice trembled. “I thought… I thought you’d be okay,” he said.

I stared at him, and I felt something inside me finally settle. Not peace, exactly, but certainty.

“You thought I’d be okay,” I repeated softly. “In the Atlantic. After surgery. Because your wife whispered about sharks.”

David’s eyes filled with tears then, and for a second I saw genuine fear. “I’m sorry,” he said, and it sounded real, finally, not corporate.

I watched him cry and felt… nothing like relief. If anything, it made me sadder, because it meant he wasn’t a monster. He was worse in a way. He was a man who could do monstrous things and still think he deserved forgiveness because he felt bad afterward.

“I believe you’re sorry,” I said, and my voice surprised even me with how calm it was. “But being sorry doesn’t fix what you broke.”

He looked up, desperate. “What can I do?” he asked.

I held his gaze. “You can live with it,” I said. “You can become someone who would never do it again. You can stop trying to take what isn’t yours. You can stop pretending your needs justify harm. And you can accept that I may never let you close enough to hurt me again.”

David’s face crumpled. “You’re my mother,” he whispered.

I nodded. “Yes,” I said. “And I’m also a person.”

We sat in silence after that. Ellen watched quietly, her expression unreadable. David wiped his face like a child. I felt a strange tenderness rise in me, not for him as he was, but for the fact that I had once held him as a baby and believed, truly believed, that love would be enough.

It isn’t. Sometimes it isn’t.

When the meeting ended, David stood, hesitated, then said, “I don’t know who I am without this,” and he didn’t mean without me, not really. He meant without money. Without access. Without the illusion of entitlement.

I didn’t respond. There was nothing to say that wouldn’t become a script in his mouth.

After he left, Ellen asked me, gently, “How do you feel?”

I thought about it. I looked at the harbor through the glass. I listened to the faint hum of the city below. I took a slow breath.

“I feel like I survived something I shouldn’t have had to survive,” I said. “And I feel like I’m done pretending.”

That’s the truth. That’s the part people don’t put in headlines.

I don’t tell this story because I want pity. I don’t even tell it because I want revenge, though I’d be lying if I said revenge didn’t taste sweet sometimes, in a bitter way. I tell it because I learned something that I wish I’d learned earlier, before I signed anything in a hospital bed, before I gave away houses and checks and chances.

The lesson is simple, and it’s ugly: some people will wear love like a costume if it gets them what they want. Sometimes those people share your blood. Sometimes they sit at your table. Sometimes they call you Mom.

And the second lesson, the one that saved me, is also simple: preparation is love too. Boundaries are love too. Paperwork can be love too, when it protects your future self.

I still live in Beacon Hill. I still know every elevator chime. I still notice which neighbors judge the recycling bins. Life looks normal from the outside. People still smile at me in the lobby. The river still reflects the sky. The city still pretends it isn’t sentimental.

But inside, I’m different now.

Sometimes, on certain Tuesdays, when the air smells like salt and the sun hits the chrome of a passing car just right, my stomach turns. I see the yacht again. I hear the engines. I feel the cold.

And then I remember something else too. I remember the helicopter. I remember Ellen’s voice. I remember Frank’s steady presence. I remember sitting in my armchair, dry and still, watching the door, refusing to disappear.

They thought they could corner me. They thought they could push me out of the story of my own life and take what they wanted.

But when they came home, I was already waiting.

With a gift.

And with the truth.

And after I said that, after the door clicked shut and their footsteps faded down the hallway, I sat there like my body forgot it was allowed to move. It’s strange what shock does, not the dramatic kind, not the kind you see on TV where people clutch their chest and gasp, but the quiet kind where your brain is still trying to file the moment into a category it understands, and it can’t, so it just stalls.

Ellen crouched beside me again, eyes searching my face the way a doctor does when they’re checking for concussion.

“Margaret,” she said softly. “Look at me.”

I did.

“Can you breathe?” she asked.

I laughed, one short sound that surprised even me. “I can,” I said. “Which is not something I was confident about a few hours ago.”

Ellen’s expression shifted, just a fraction. Not amusement. Relief. She squeezed my hand once, firm, like she was anchoring me to the present.

Samuel stayed standing near the fireplace, hands folded, calm as always, but I saw the tension in his jaw. Frank was at the window, watching the street below like he expected David and Vanessa to double back with a battering ram. Frank always looks like that, though. Frank would watch a children’s parade like it was a potential ambush.

The apartment felt too bright, too normal. The lamp was on. The rug was the same rug I’d chosen ten years ago because it reminded Robert of his grandmother’s house in Maine. The air smelled faintly of Earl Grey and lemon cleaner. A normal living room should not be the setting for a betrayal that involves open water and lawyers and revoked access cards. But life doesn’t coordinate its props.

Ellen straightened, smoothing her blazer like she was putting herself back into professional mode. “We’re going to do three things tonight,” she said, brisk now. “One, you’re going to eat something, because your body needs it even if you don’t feel hungry. Two, we’re going to document what happened here, because if they claim anything later, we want a clear timeline. Three, you’re going to sleep, and I don’t care if it’s two hours or eight, but you need rest.”

“I’m not hungry,” I said automatically, because that’s what people say when their world splits open.

Ellen gave me a look. “Margaret,” she said, and it was the same tone Robert used when I tried to “work through” a fever. “Eat.”

Frank disappeared into the kitchen like it was a mission. He came back with a plate that looked like something a practical man would assemble from whatever he found without asking permission. Toast, peanut butter, a banana. Water.

“I’m sorry,” I said, because my manners have outlived my trust.

Frank shrugged. “Don’t be,” he said. “Eat the toast.”

So I did. I took small bites. The peanut butter stuck to the roof of my mouth. My throat felt tight, but swallowing forced my body to remember it was alive.

While I ate, Ellen pulled out her folder and started flipping through papers with the speed of someone who has spent decades turning chaos into order. Samuel opened his own slim binder, the kind that makes you feel like he could shut down a small corporation with a single page. They weren’t just there to comfort me. They were there to hold the line.

Ellen slid one document toward me. “This is the formal revocation notice for property access,” she said. “You’ve already signed it, but I want you to understand it.”

I looked at the page, black ink on white paper, words that felt both familiar and surreal. As if my life had become something you can correct with a letter.

“Do you know what’s making me sick?” I said, and my voice surprised me with how steady it sounded.

Ellen glanced up. “What?”

“It’s not the ocean,” I said. “It’s not even the shove. It’s the fact that they walked in like they owned the place. Like they’d already rehearsed the next day.”

Ellen nodded slowly. “That’s why we’re being thorough,” she said. “Entitlement thrives in fog. We’re removing the fog.”

Samuel cleared his throat. “Also,” he added, “the financial side is locked down.”

“Define locked down,” I said, because I’ve lived long enough to know words like locked down can be comforting and vague at the same time.

Samuel didn’t smile. He never does. “The accounts that require dual authorization remain inaccessible to anyone but you and me,” he said. “Any attempted access triggers alerts. The discretionary distributions David used to request have been suspended. All communications from him or Vanessa to institutions on your behalf are now flagged as unauthorized.”

“Flagged,” I repeated, and the word tasted like vindication and grief at the same time.

Ellen added, “And the building incident is documented too. Security cameras captured their entry, their reaction to seeing you, their argument, and their exit. We also have audio from the room.”

I blinked. “Audio?”

Frank lifted a shoulder. “Your place has a security system,” he said. “You approved it after the hospital situation. It records common areas.”

I stared at him. “Frank,” I said, half stunned, half grateful.

He looked almost embarrassed. “You said you wanted to feel safe,” he said. “This is what safe looks like.”

Safe looks like cameras and lawyers and peanut butter toast. Wonderful.

That night, I didn’t sleep much. I tried. I lay in bed with the lights off and the city outside my windows doing its normal thing, headlights sweeping across brick, distant laughter from a late-night group stumbling home, the occasional siren that always sounds like it’s going somewhere important. My body was exhausted, but my mind wouldn’t stop replaying it, the tilt of the world, the rush of cold air, the sound of engines. Every time I started to drift, my brain would yank me back like it didn’t trust unconsciousness.

At some point, I got up and padded to the kitchen in my socks, because I couldn’t stand the bedroom anymore. I made tea I didn’t drink. I stood by the window and stared at the streetlights and tried to remember what life felt like before I started treating my own son like a threat profile.

You might think money prepares you for betrayal. It doesn’t. Money prepares you for audits. Money prepares you for lawsuits. Money prepares you for people asking for things. It does not prepare you for the way your heart keeps reaching for someone even after they’ve proven they’ll let go.

Around three in the morning, Ellen texted me. One line.

You’re doing great. Stay inside. Doors locked. Frank is outside your unit.

I stared at it for a long time, because it was so simple and so steady. I didn’t realize how much I needed someone to say, Stay inside, like I was a child after a nightmare. I texted back, Okay. Thank you.

Then I did something else that surprised me. I opened Robert’s old desk drawer and pulled out a small notepad where he used to jot down reminders, the kind with the spiral binding. It still smelled faintly like his cologne, that clean, woodsy scent that always made me think of cedar closets and early mornings.

I wrote one sentence, in my own handwriting, as if putting it on paper would make it stick.

They tried to erase me. They failed.

I stared at the sentence until my eyes burned. Then I closed the notepad and put it back, like it was a fragile thing.

The next morning, the world had moved on without my permission. That’s one of the rudest things about life. It keeps going even when you’re still trying to process the last twenty-four hours.

My phone had messages, voicemails, missed calls. Some were from numbers I recognized. Some were unknown. There were emails too, a flood of them, because when you’re wealthy and something unusual happens, it becomes public faster than you’d think. Hospitals talk, not officially, but people are people. Coast Guard personnel have spouses. EMTs have cousins. Somebody always knows somebody.

Frank knocked gently and stepped into my foyer like he belonged there, which he did at this point. He held up his phone.

“There’s a news item,” he said.

I felt my stomach clench. “About me?”

Frank nodded. “Not your name,” he said. “Not yet. But it’s close.”

He showed me a short local segment. A helicopter rescue off the Massachusetts coast. An older woman recovered from the water. No details. No accusations. Just a clean little story about emergency services doing their jobs.

I watched it and felt detached, like I was watching footage of someone else’s life.

Ellen arrived an hour later, coffee in hand, hair perfect, eyes slightly tired. She sat at my kitchen counter and took control of my day like she was managing a crisis for a corporation, except the corporation was my nervous system.

“We need to assume they will try a narrative,” she said.

“I hate that word,” I muttered.

“I know,” Ellen said. “But it matters. This isn’t just about what happened. It’s about what they try to make people believe happened.”

Samuel arrived next, carrying a thin folder. He looked like a man delivering a bank statement, which was his natural state.

“Two attempted calls,” he said, placing his phone on the counter. “One from David. One from Vanessa. Both to an institution that handles one of your secondary accounts. They were denied access. The calls were recorded by the institution, per policy.”

Ellen’s eyes narrowed slightly. “Already,” she said.

“Already,” Samuel confirmed.

I wrapped my hands around my mug, not because I needed warmth, but because I needed something to hold. “So they’re still trying,” I said.

Ellen nodded. “Yes,” she said. “And we’re going to keep meeting them with walls.”

Frank, from the doorway, added, “And we’re going to keep meeting them with cameras.”

At noon, Ellen asked me if I wanted to go for a short walk.

“You’re joking,” I said.

“I’m not,” she replied. “We’re going to do it carefully. Frank will be nearby. But you need air. Otherwise your brain will turn this apartment into a bunker.”

I wanted to argue. I wanted to hide. I also didn’t want to feel like a person who hides in her own home because her son became dangerous.

So I said yes.

We walked along the edge of Boston Common, the trees bare in that winter way that makes everything look more honest. The air was sharp. The city was doing its usual midday shuffle. Tourists with Red Sox hats even in the wrong season. A man selling hot dogs. College kids with backpacks and coffee, moving like they were late to everything.

Ellen walked beside me, hands in her coat pockets, looking like a woman going to lunch, not a lawyer escorting a client who survived an attempted disappearance. Frank was across the street, pretending to be interested in his phone. Samuel wasn’t with us. Samuel doesn’t do strolls. Samuel does documentation.

As we walked, I caught myself flinching at loud sounds, at sudden movement. My body kept anticipating danger like it was a job. I hated it. I hated feeling jumpy in my own city.

Ellen noticed. “It’s normal,” she said.

“Normal,” I repeated, and I almost laughed. “Define normal.”

Ellen’s mouth curved slightly. “Normal for trauma,” she said. “Which is not a category you asked to join, but here you are.”

We passed a group of kids playing on the ice rink, their laughter bright and careless. I watched them for a moment and felt tears sting my eyes, not because of them, but because I wanted that kind of carefree, that kind of belief that the world is stable under your feet.

“Do you want to stop?” Ellen asked.

I shook my head. “No,” I said. “Keep walking.”

We walked past the Public Garden too, the swan boats docked and still, waiting for spring. That always gets to me, those boats, because they’re so old-fashioned and stubbornly cheerful, like Boston refuses to fully modernize its whimsy. Robert used to tease me about them. He’d call them “the city’s annual proof it still has a heart.”

I swallowed hard and kept walking.

Back home, the calls started in earnest.

David called from a blocked number. I didn’t answer.

Vanessa left a voicemail that began with a syrupy, “Margaret, we’re so worried,” and ended with a colder, “You’re making this much worse than it needs to be.”

Ellen listened to it once and then said, “Save it.”

I stared at her. “As evidence?”

“Yes,” she said. “And as a reminder. When you start doubting yourself, play it again.”

I hated that she was right.

By the third day, the story changed shape. Someone leaked my name. Not officially. Not in a formal statement. It just appeared in a gossip column, tucked into a paragraph like it was a fun detail. Boston society pages have always been a strange mix of charity and cruelty.

Billionaire widow rescued off the coast. Beacon Hill resident. Prominent philanthropist.

My phone turned into a siren.

Old friends called, voices tight with concern and curiosity. People I hadn’t heard from in years suddenly remembered my number. A woman from a hospital fundraiser left a message that was ninety percent “Oh my goodness” and ten percent “We should do lunch.”

I ignored most of them. Not out of spite. Out of exhaustion.

Ellen sent a short statement to a few trusted contacts. Something bland and factual. Margaret Harrison experienced a medical emergency during a private family outing. She is recovering at home. She requests privacy.

Medical emergency. That phrase again. It made me want to scream. But I understood why Ellen used it. It avoided accusations until we had everything lined up. It didn’t give David and Vanessa a public fight to feed on.

It was strategic, and I hated that strategy had become part of my daily diet.

A week after the yacht, Ellen brought me to her office again, and Samuel joined us. Frank stayed outside in the waiting area, reading a newspaper like a man who’s trying not to look like security.

Ellen closed the door and sat across from me.

“Margaret,” she said, “we need to talk about how far you want to take this.”

I exhaled slowly. “Define take,” I said.

Ellen didn’t flinch. “Criminal,” she said. “Civil. Protective orders. Guardianship defenses. The entire structure of your estate. And, importantly, what you want the future to look like with David.”

That last part made my stomach tighten.

Samuel spoke next. “There’s also the matter of the trust’s intent,” he said. “Robert’s intent. And your intent.”

I stared at the conference room table, polished wood that reflected the light like a calm lake, and felt a wave of weariness roll through me.

“I don’t want to destroy him,” I said quietly. “I just want him to stop.”

Ellen nodded. “That’s a common feeling,” she said. “It’s also one that manipulators exploit. They count on your reluctance.”

Samuel added, “Stopping requires leverage,” he said. “Leverage requires consequences.”

I looked up. “Are you telling me I have to ruin my son to protect myself?”

Ellen’s voice softened. “I’m telling you that you’re not the one who set this in motion,” she said. “He did.”

I sat back, trying to breathe through the ache in my chest. “If I press charges,” I said, “it becomes public. It becomes… a spectacle.”

“Yes,” Ellen said. “And if you don’t, they may try again in a different way. Legal. Financial. Social.”

“Vanessa loves social,” I muttered.

Ellen’s gaze sharpened. “That’s another thing,” she said. “We have reason to believe she’s been collecting recordings. Not just on the boat. For months.”

My skin went cold. “Recordings of what?”

Ellen opened a folder and slid a printed screenshot toward me. It was a social media story frame, posted and deleted quickly, but captured by someone who followed Vanessa. The caption wasn’t overt, but it was suggestive. A clip of my hand gesturing at a dinner table, my voice faint in the background, my words cut out of context. It made me look sharp, dismissive. It made me look like the villain in a family story.

I stared at it until my vision blurred.

“I didn’t even know she posted that,” I whispered.

Ellen nodded. “She’s been testing the waters,” she said. “Seeing what narrative gets traction.”

Samuel’s voice was flat. “That’s a problem,” he said, “because traction becomes evidence in the court of public opinion, and public opinion can influence everything from juries to judges.”

“I hate that you’re right,” I said.

Ellen gave me a look that said she hates that too.