They said, “You’re getting older, so you can’t travel with us anymore. Just stay home and keep an eye on the house for us.”

They didn’t say it like a cruelty. That was the trick of it. They said it the way people say things when they’ve already decided you’ll accept them. Like it was practical. Like it was loving. Like it would be easier for everyone if you just quietly stayed in your place.

I was standing in my own kitchen when they said it, hands wet at the sink, watching my son’s wife fold their itinerary into neat little squares. The sun came in through the window over the garden, falling across the worn wood table I’d refinished myself years ago, back when my hands were steadier and my life still had a center.

“You know how airports are,” Laura added, with that bright, tight smile she used when she wanted to sound gentle while removing you from the picture. “Long lines, lots of walking. The kids get cranky. It’ll be a lot.”

My son, David, hovered near the fridge like he was deciding whether to step in or step away. He looked older lately. Not in a way that made him softer, but in a way that made him more tired of complicated feelings.

I dried my hands slowly, the towel rough against my palms. “So you’re going without me.”

“It’s just this time,” David said quickly, like he was slapping a bandage on something bleeding. “We’ll do something closer with you later. You know we will.”

Later. That word has a way of turning into never.

They told me to water the plants and double lock the doors like I was a housemaid they could count on but not bring along.

“You’re too old for long flights, Mom,” David said, and then, because he couldn’t stop himself, he added the softener: “Grandma.”

Just watch the house.

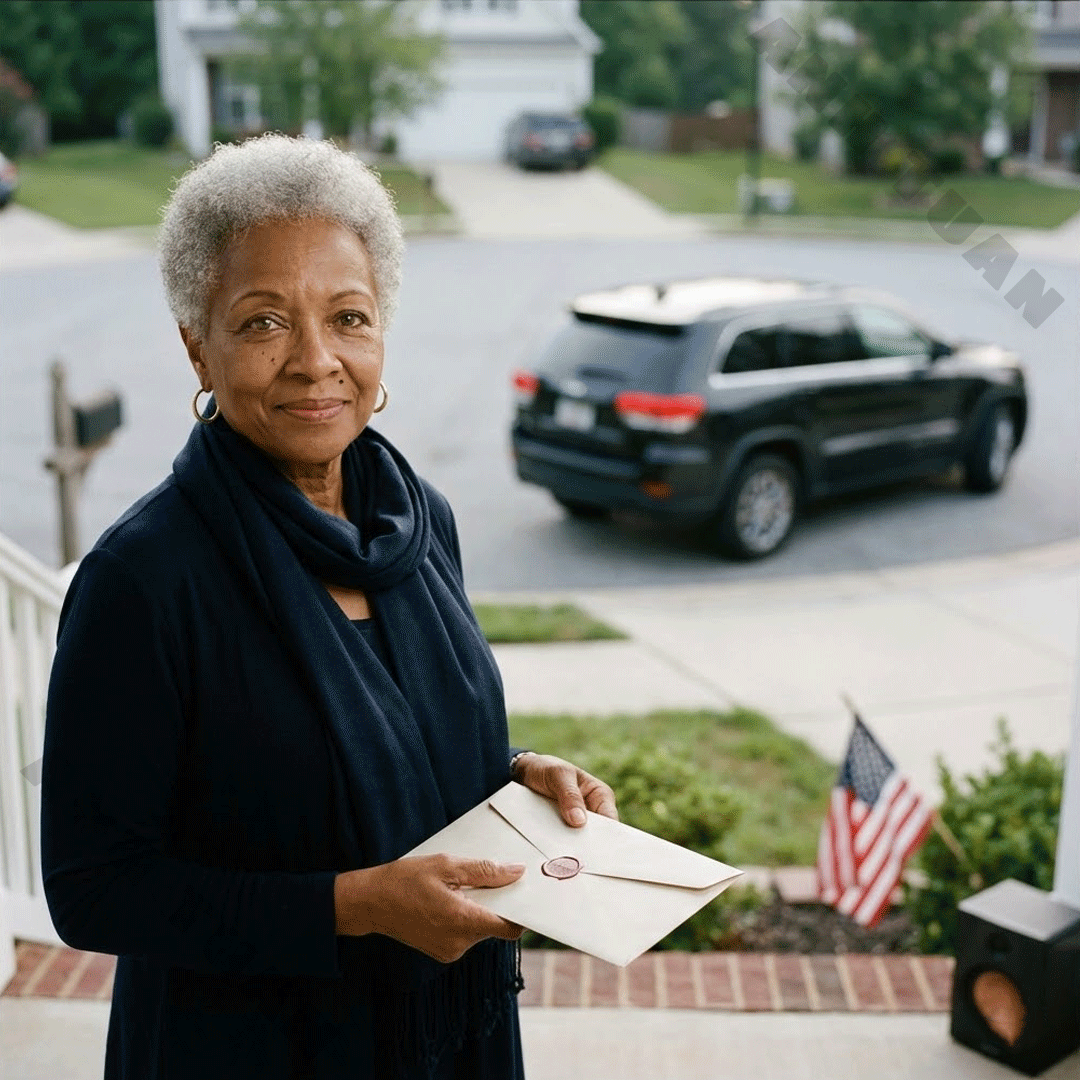

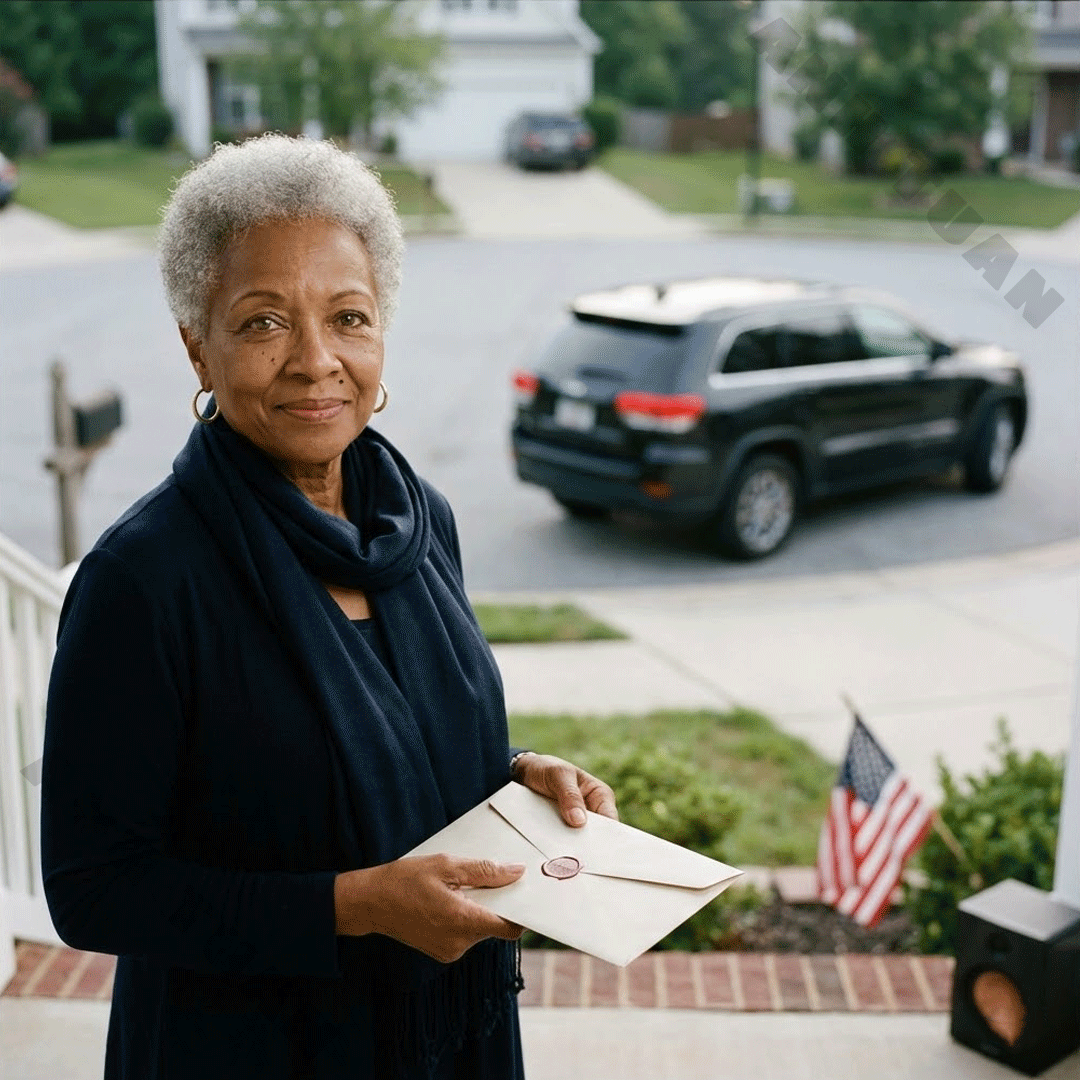

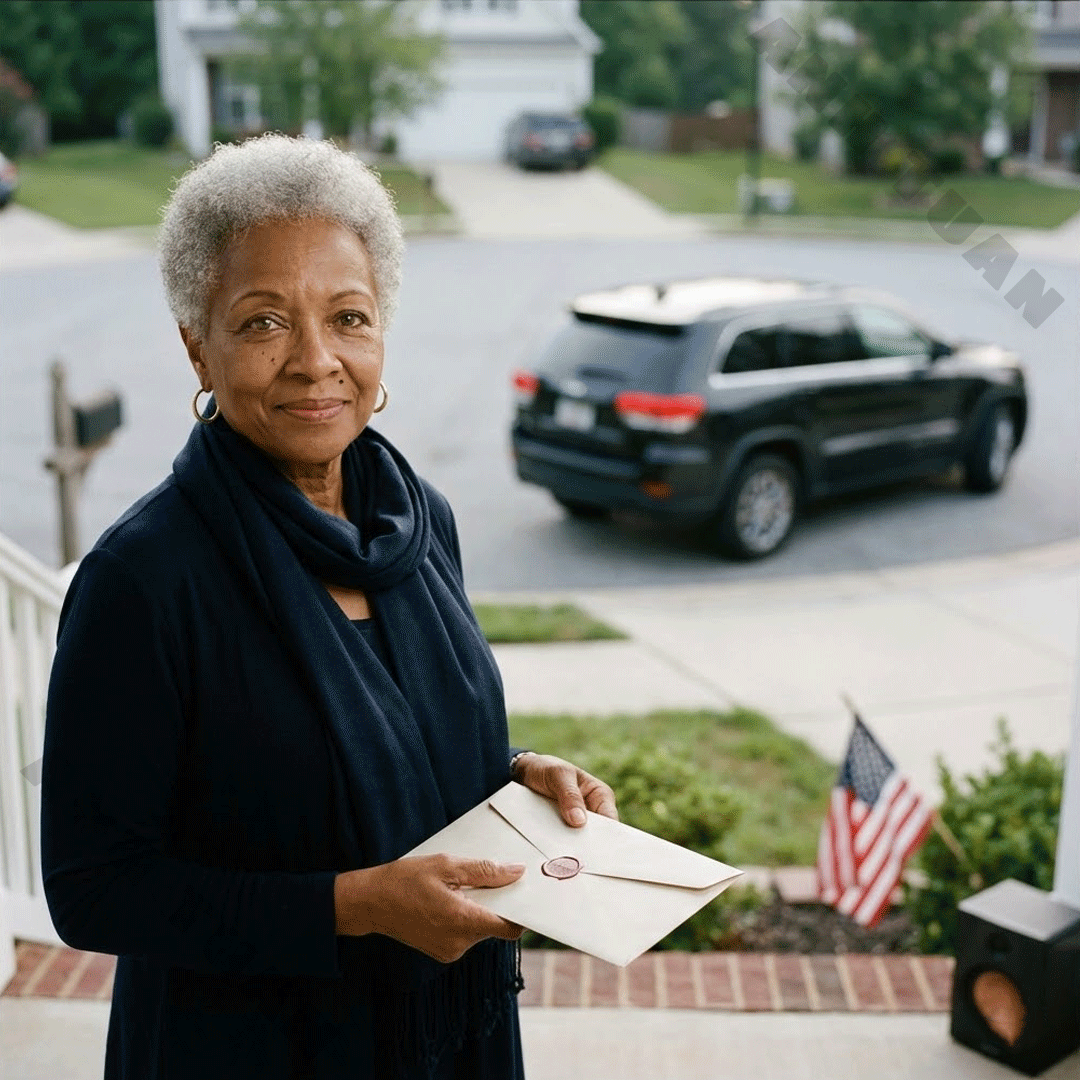

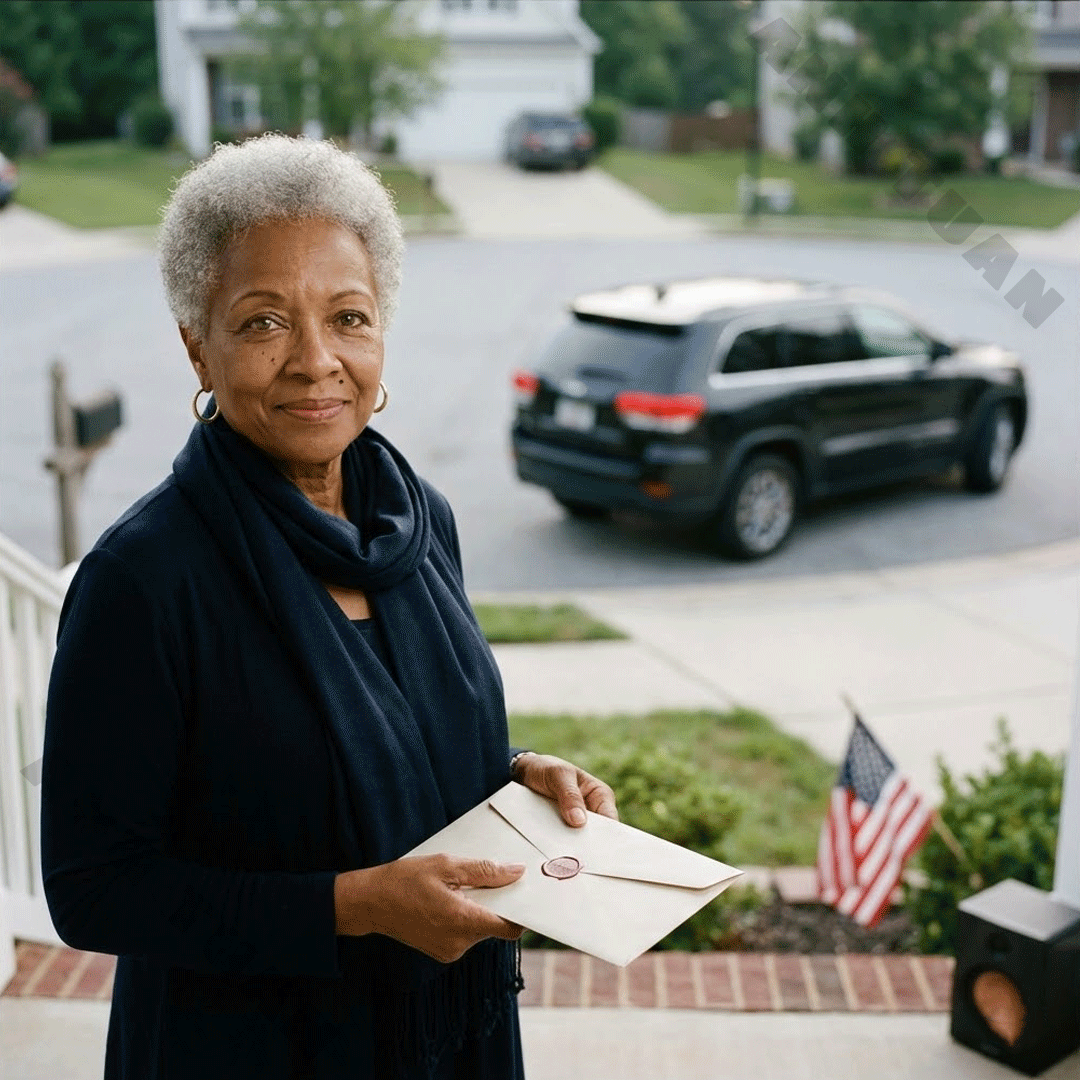

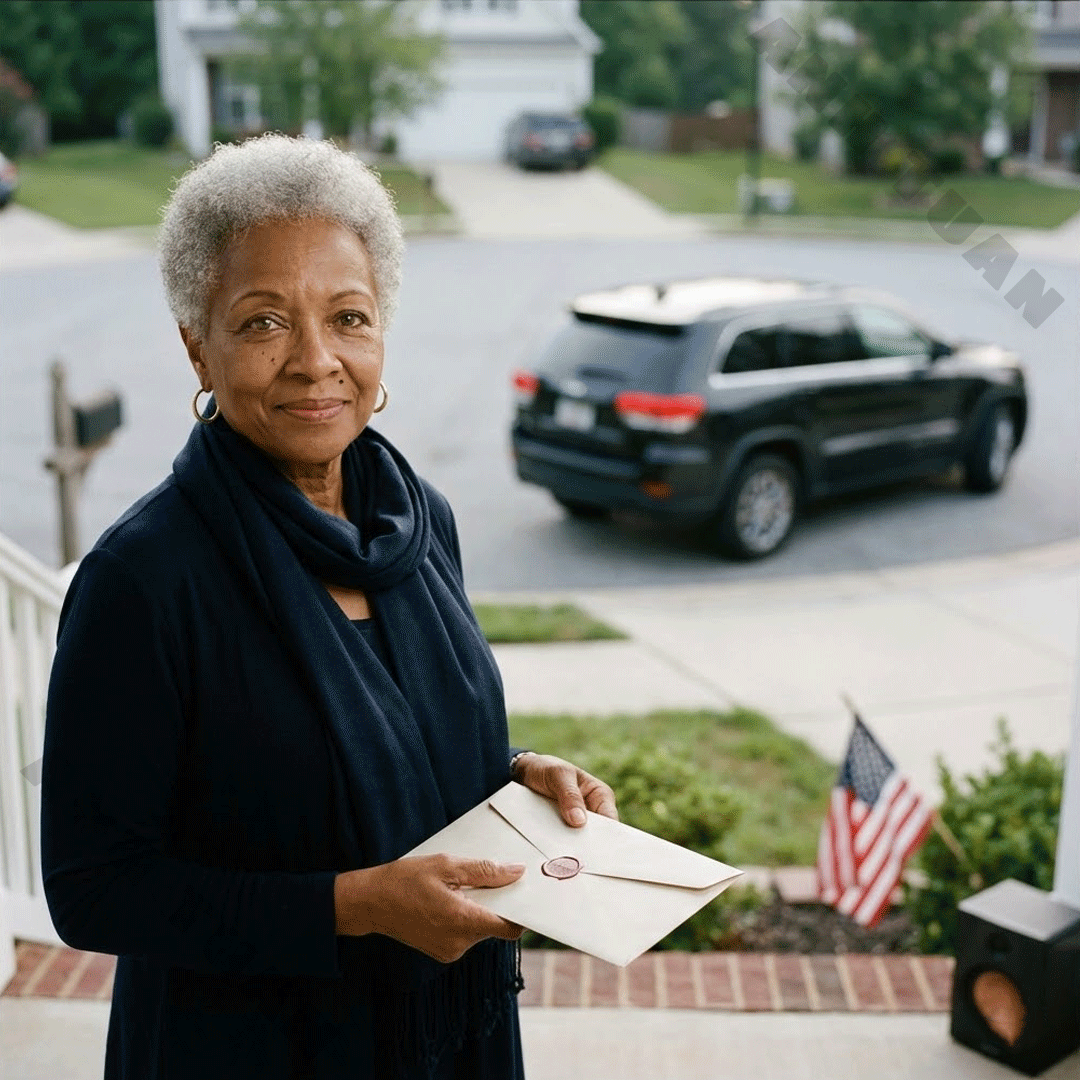

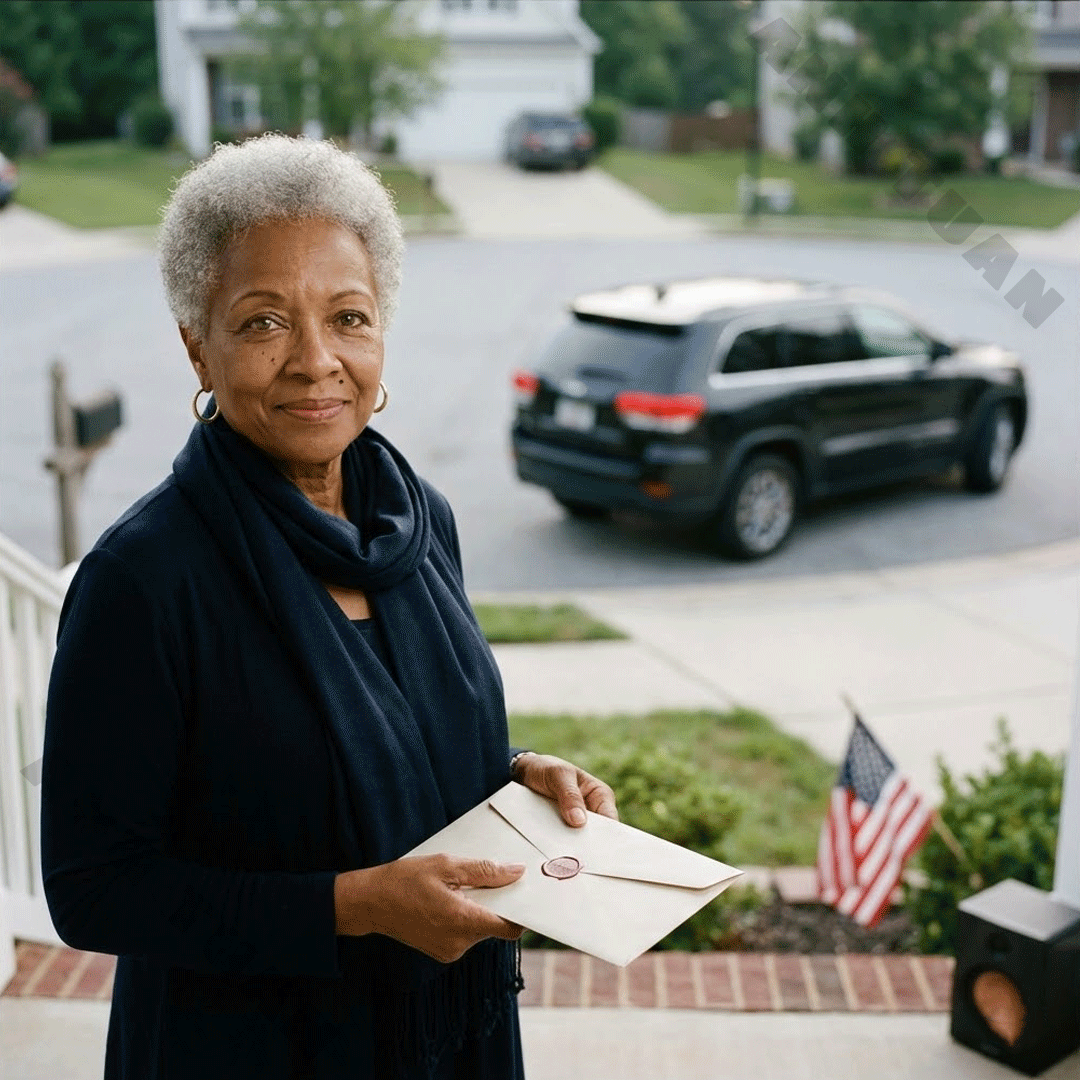

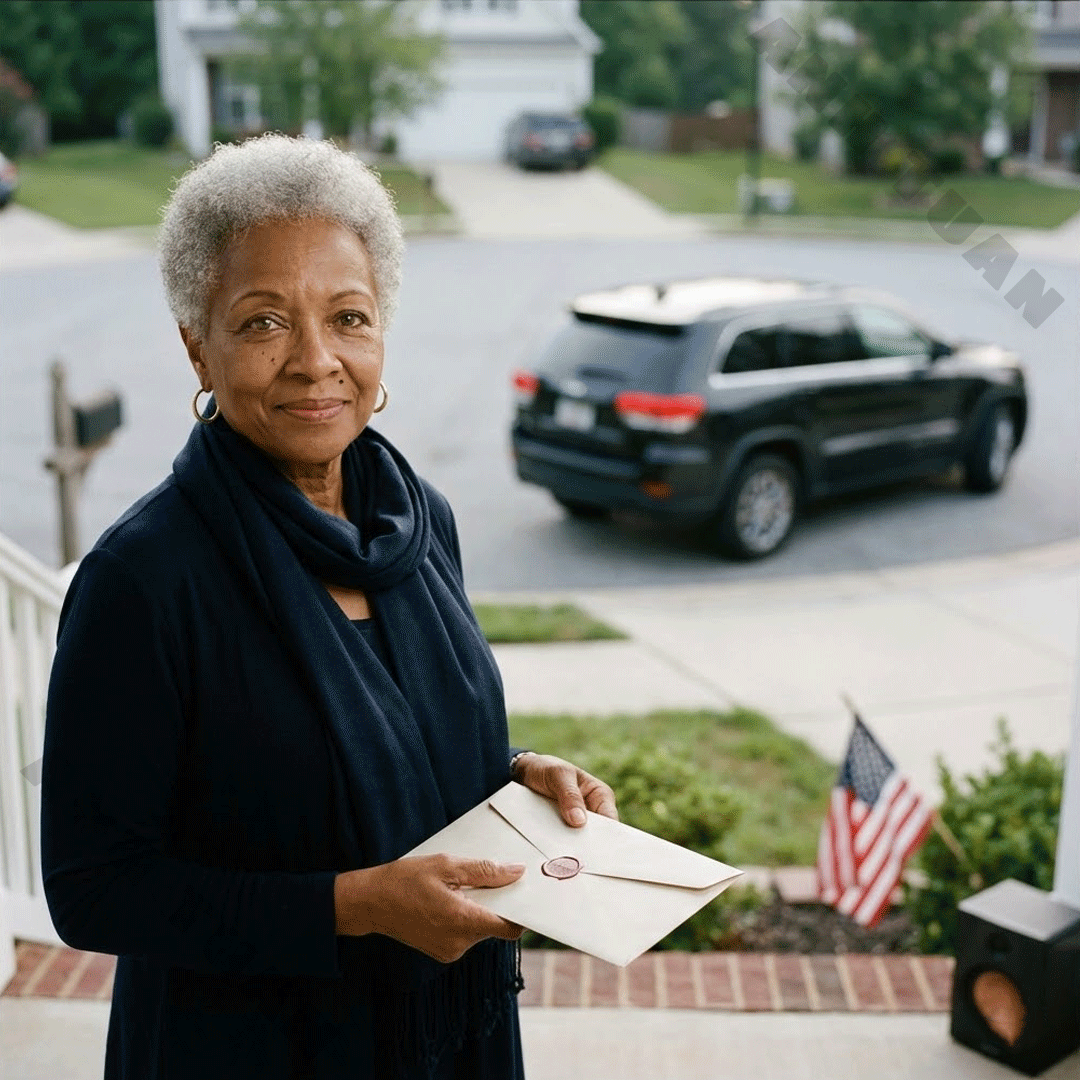

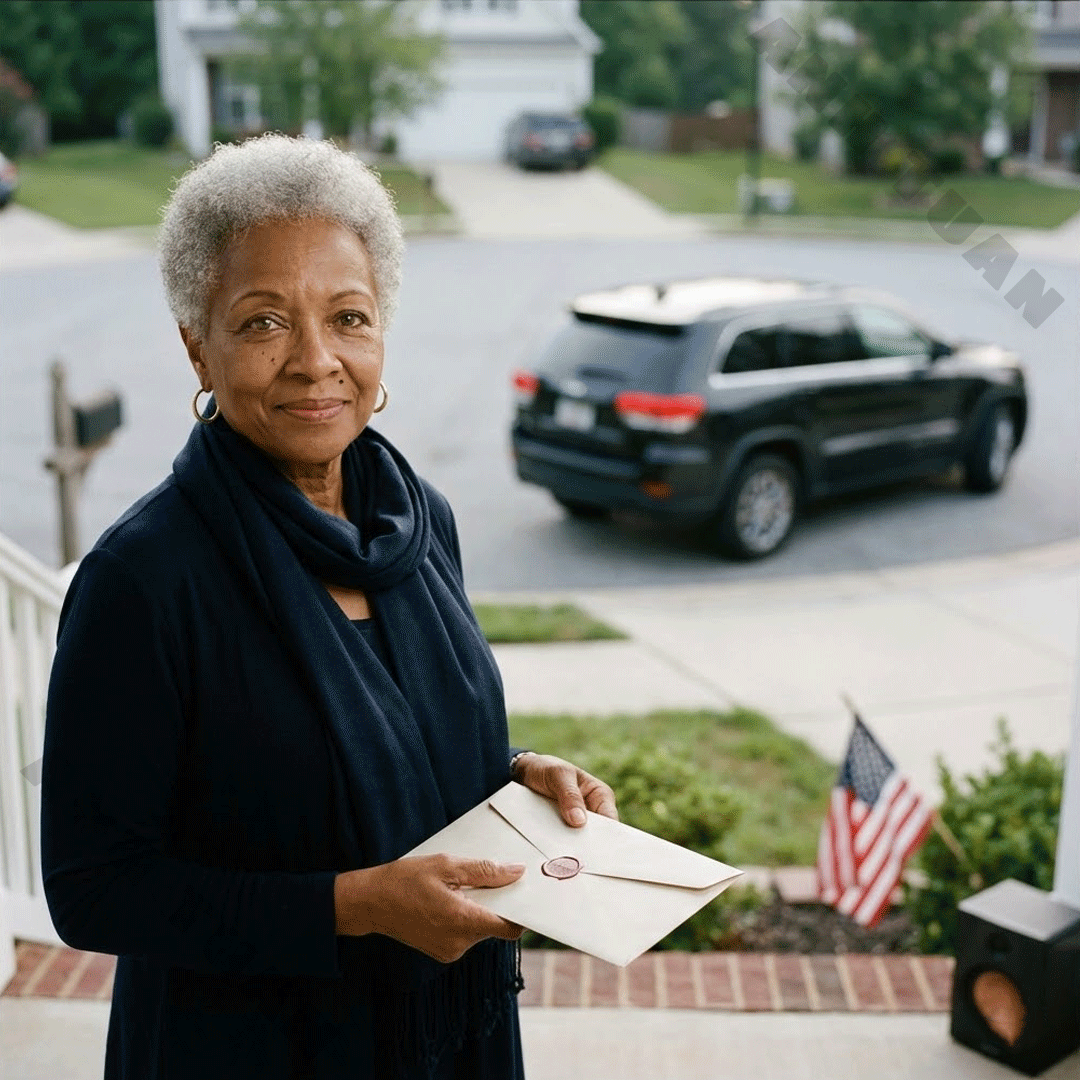

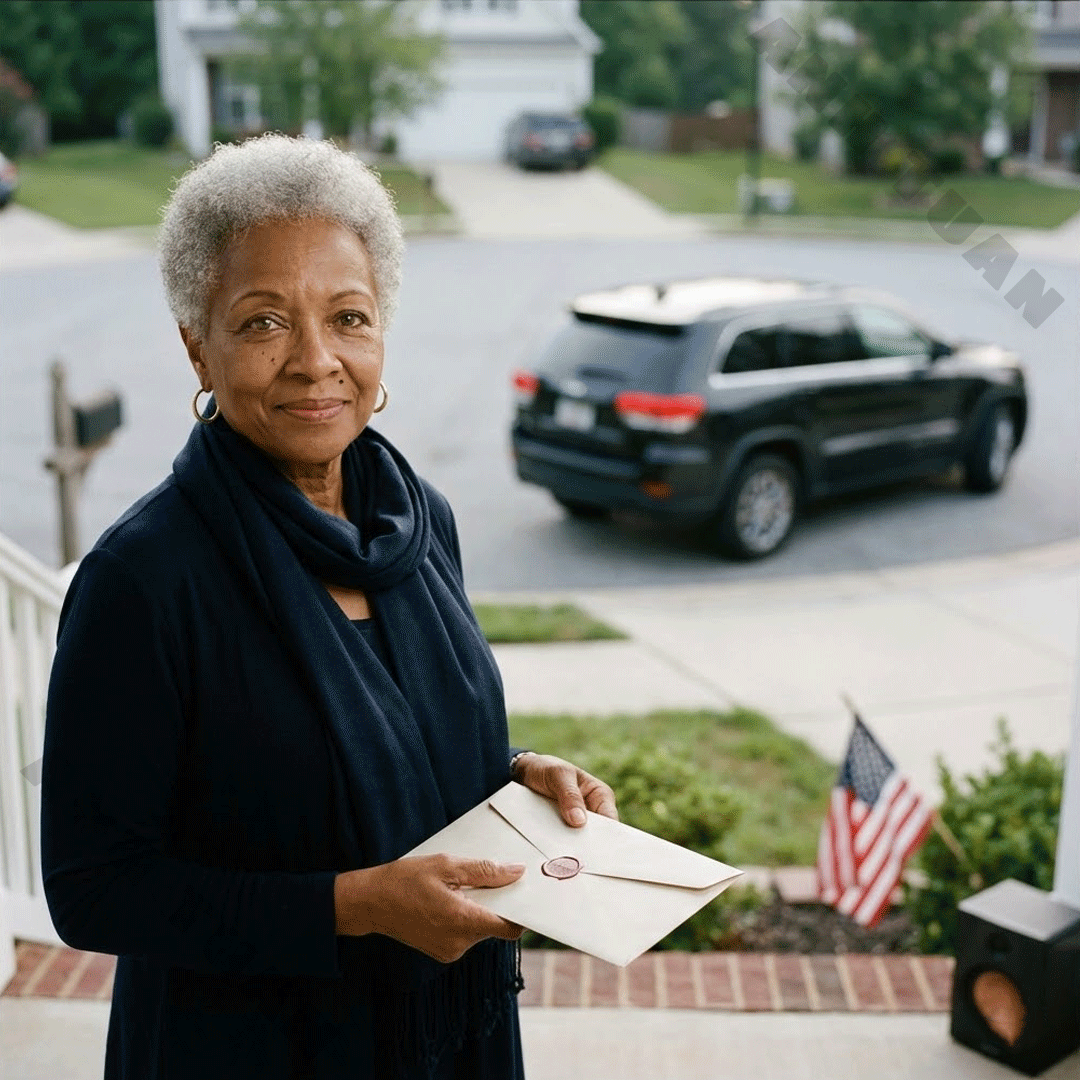

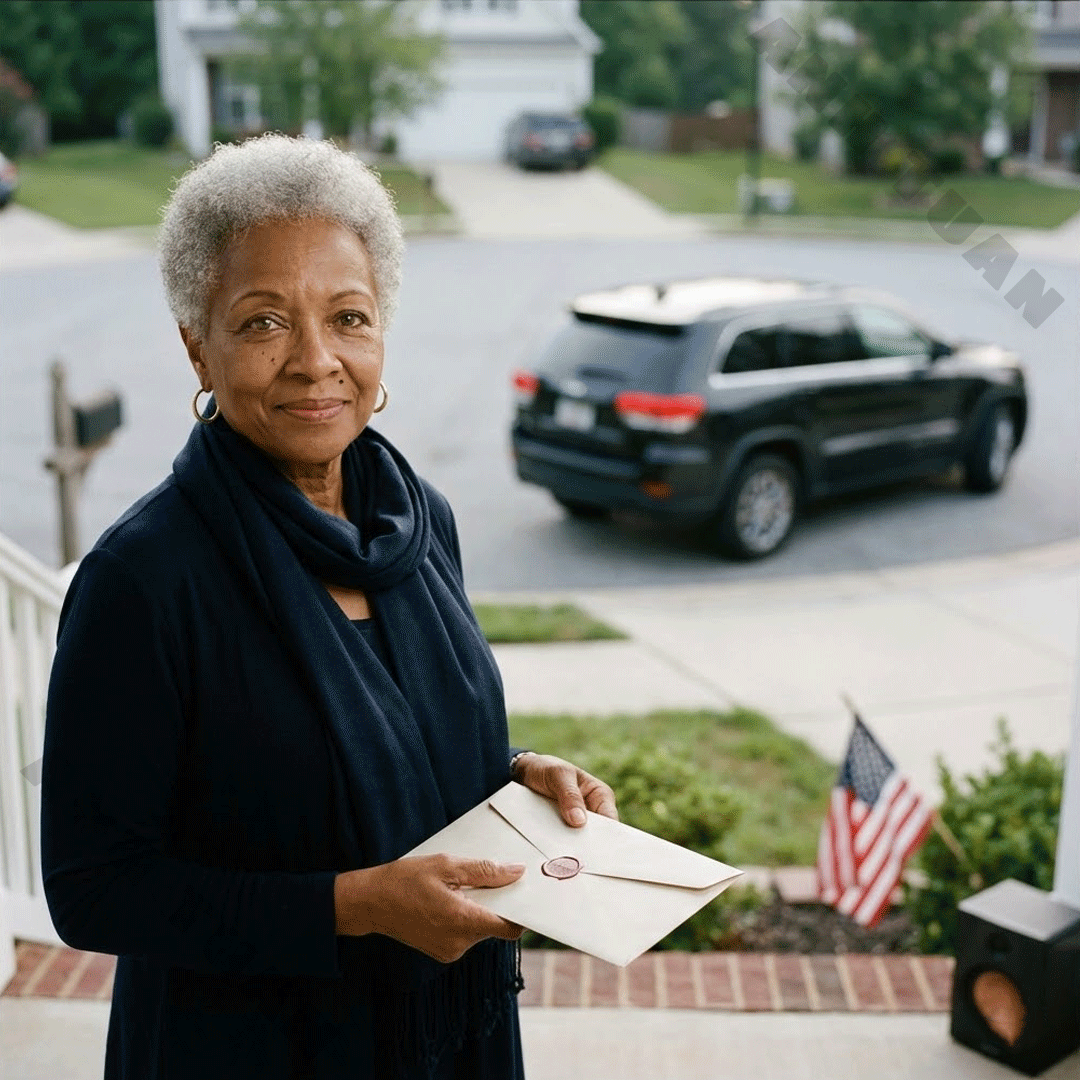

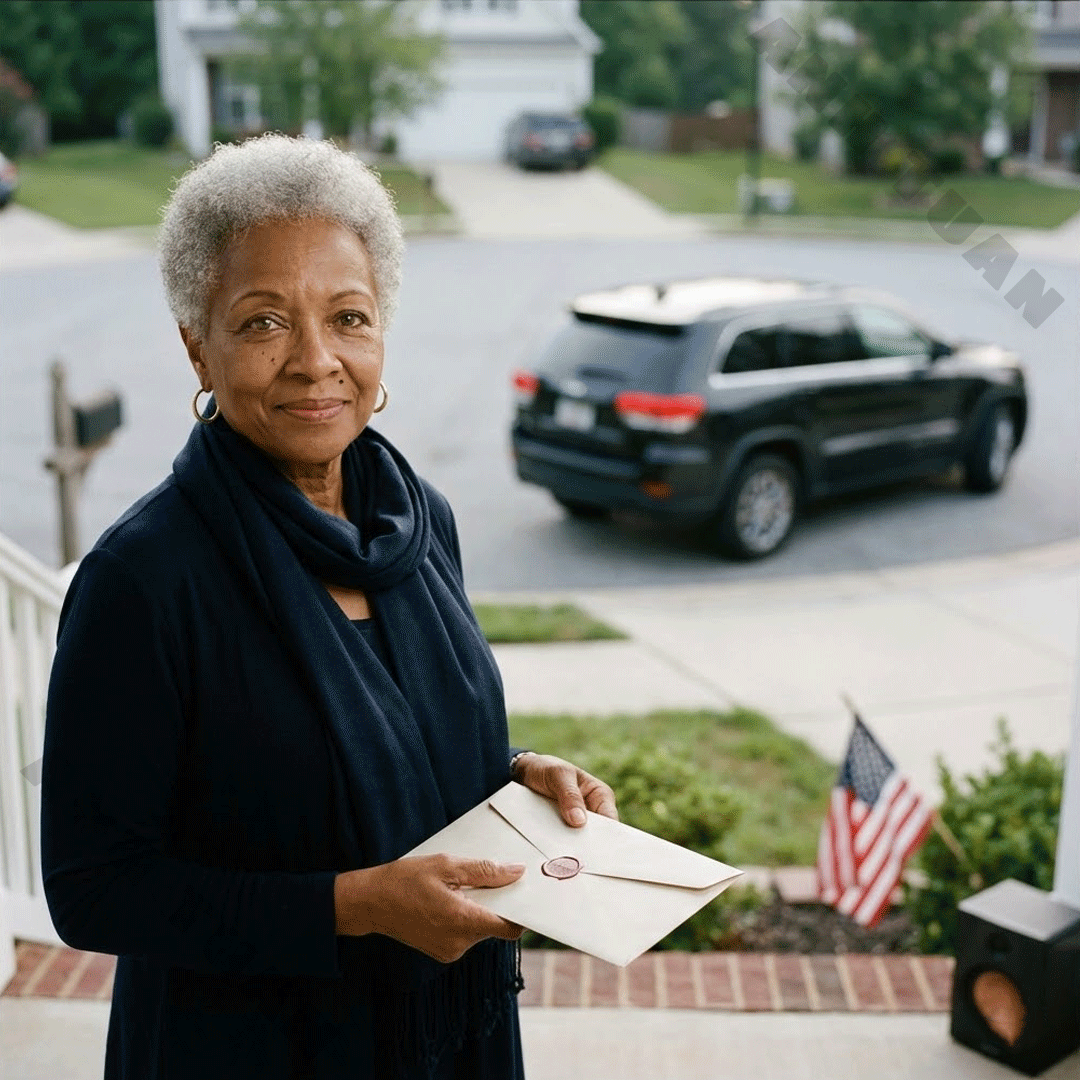

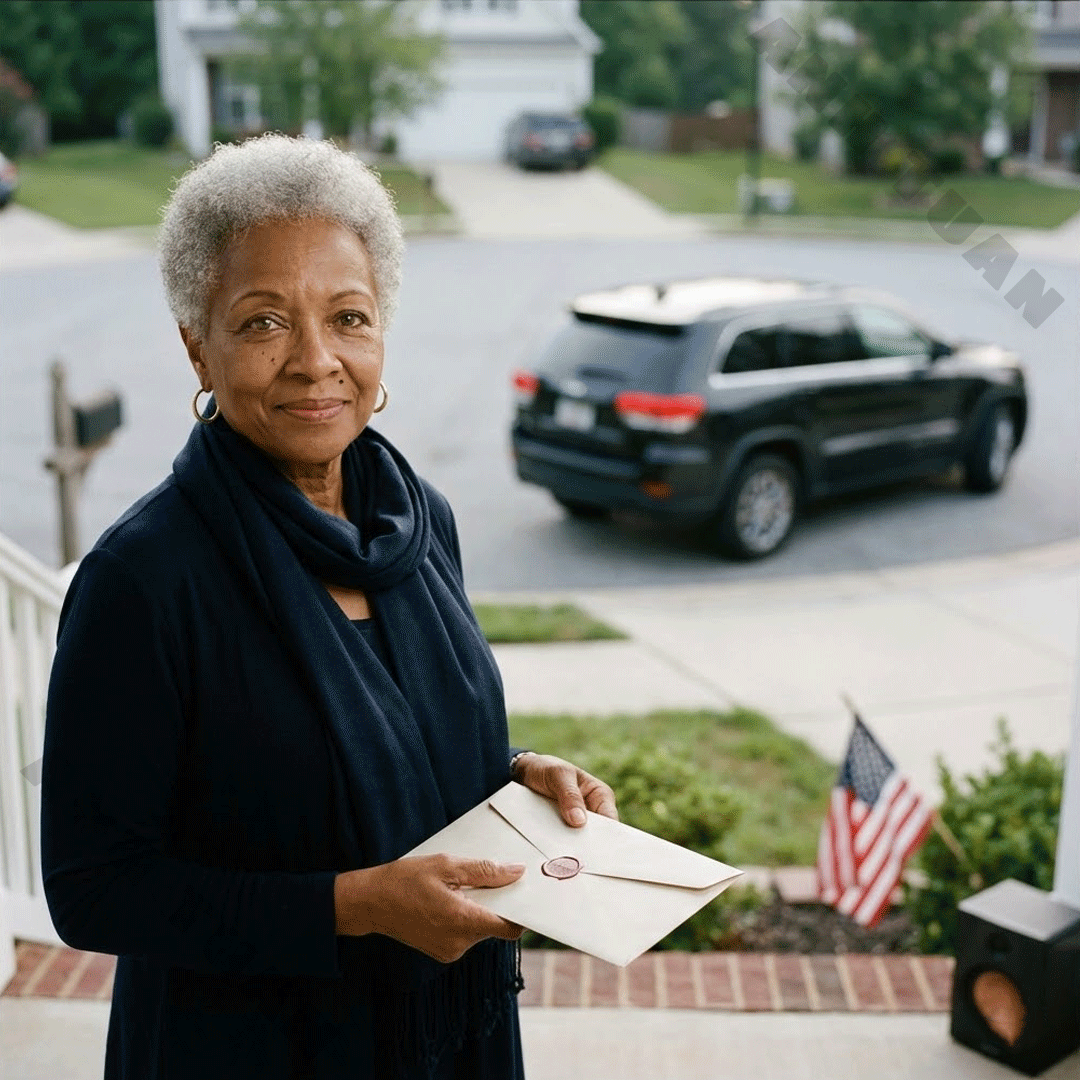

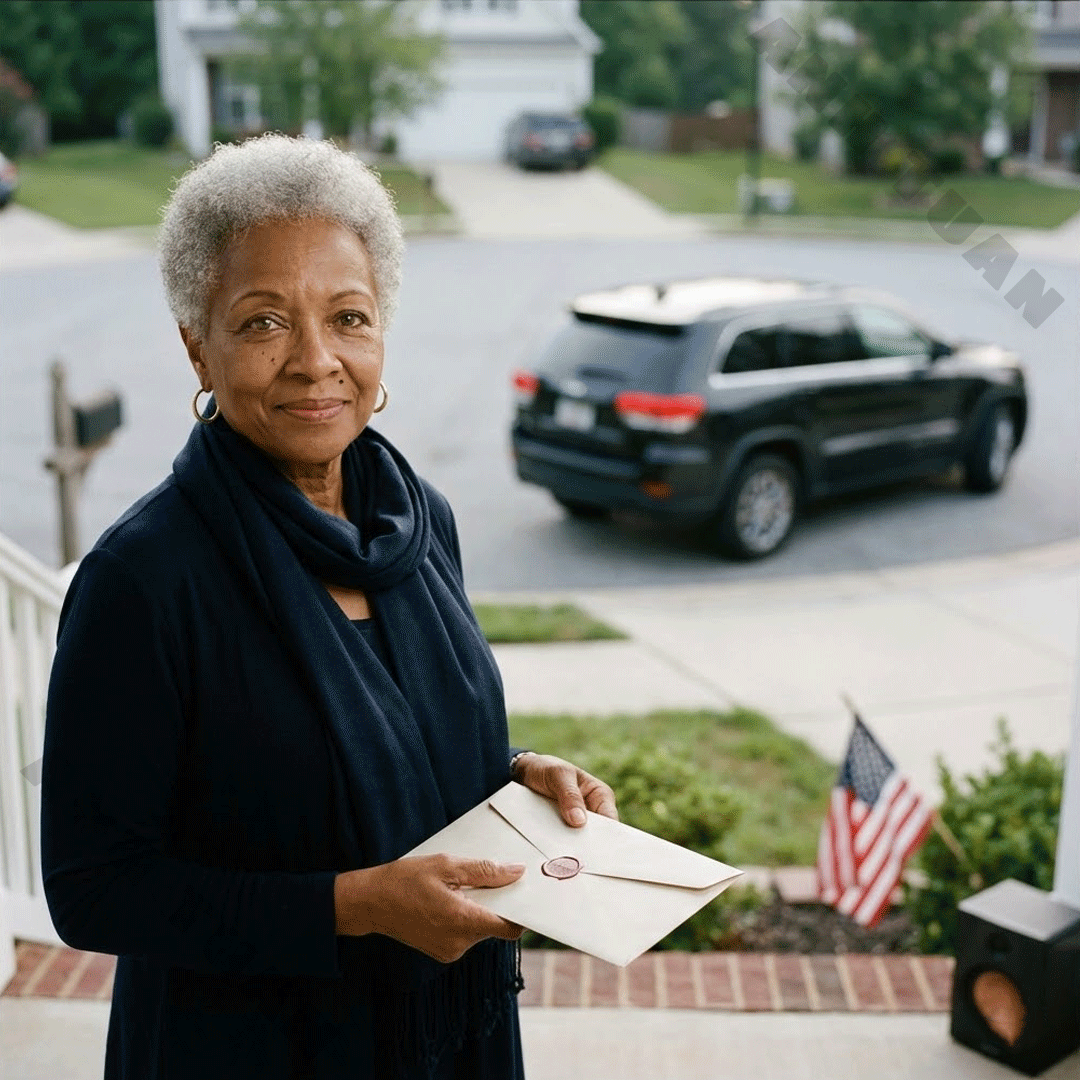

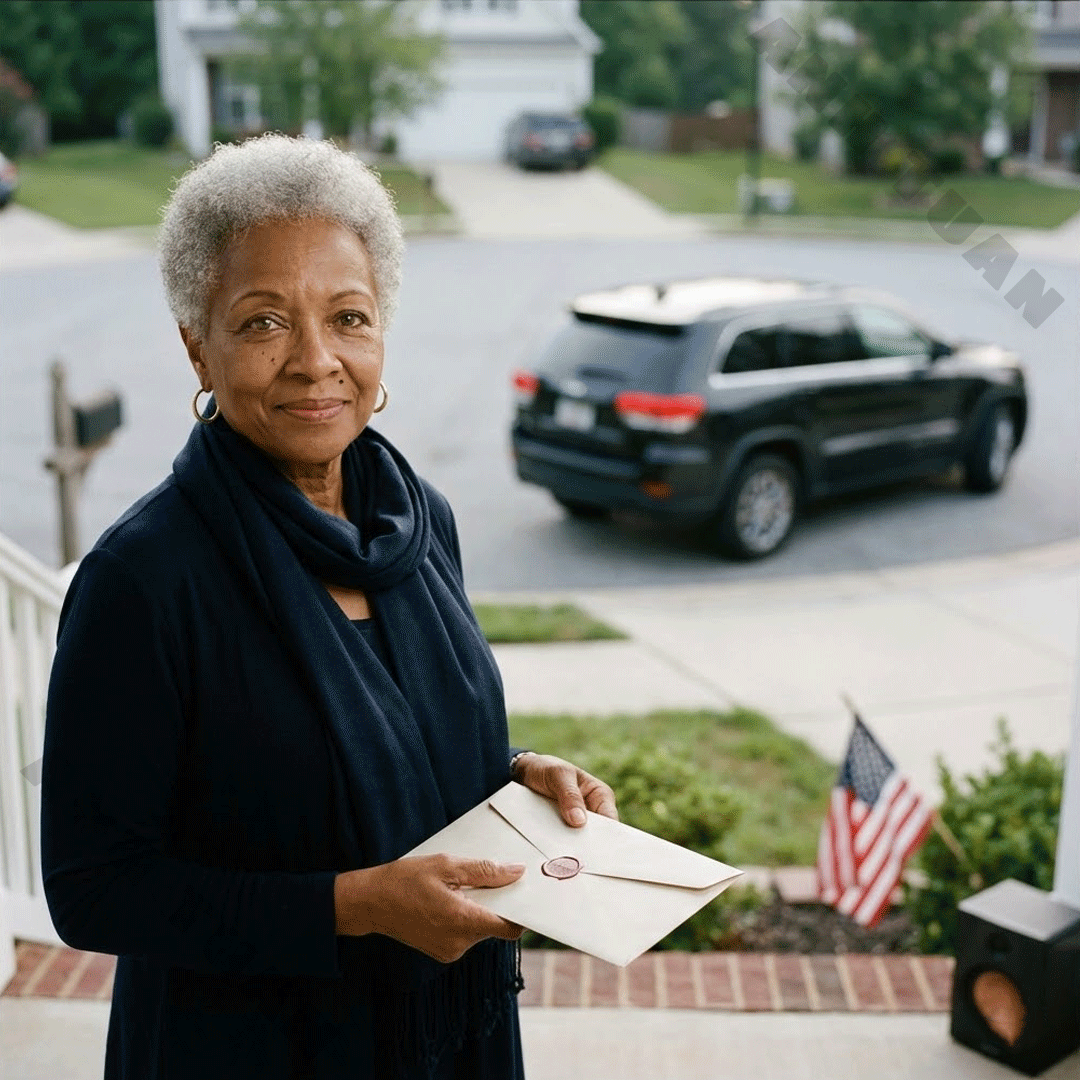

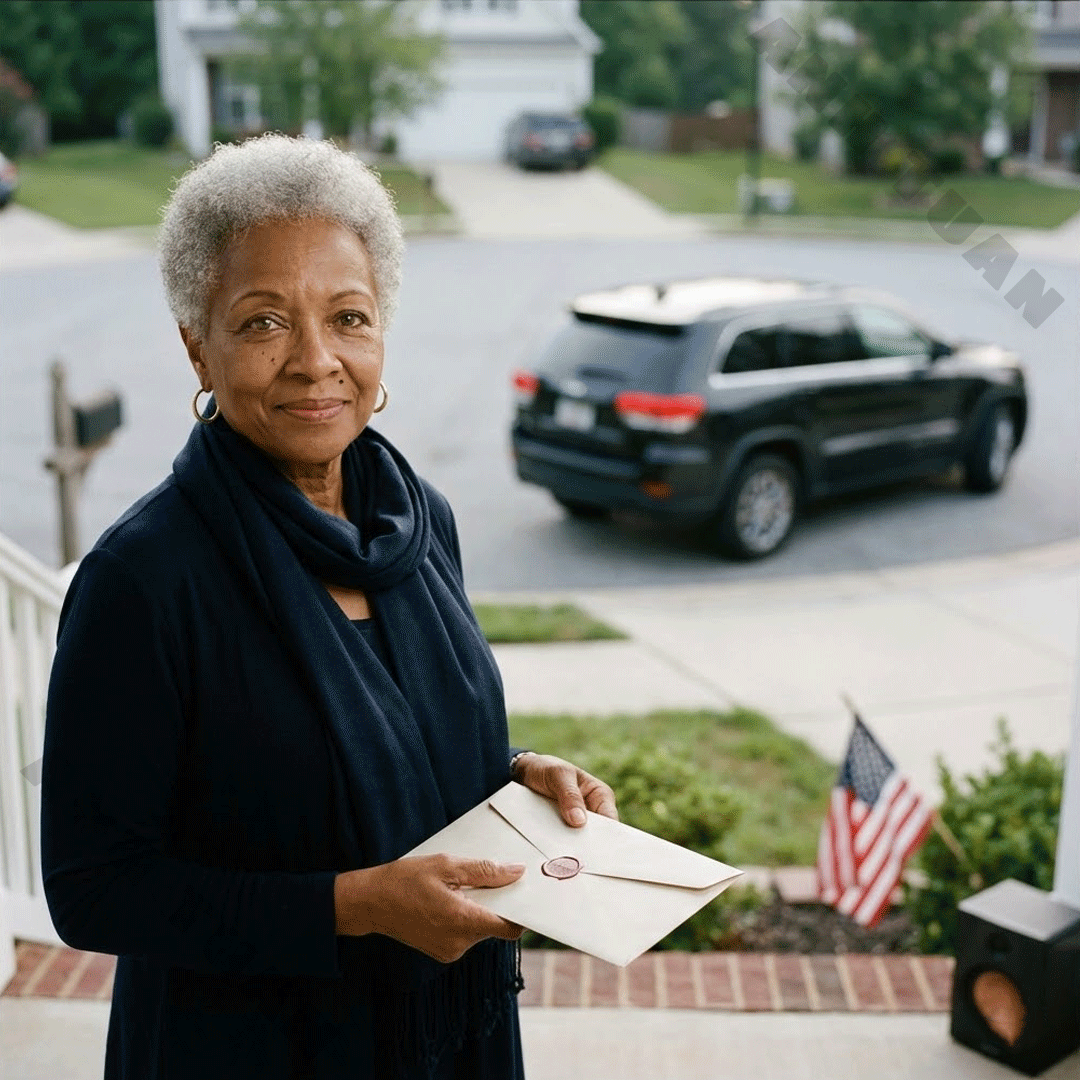

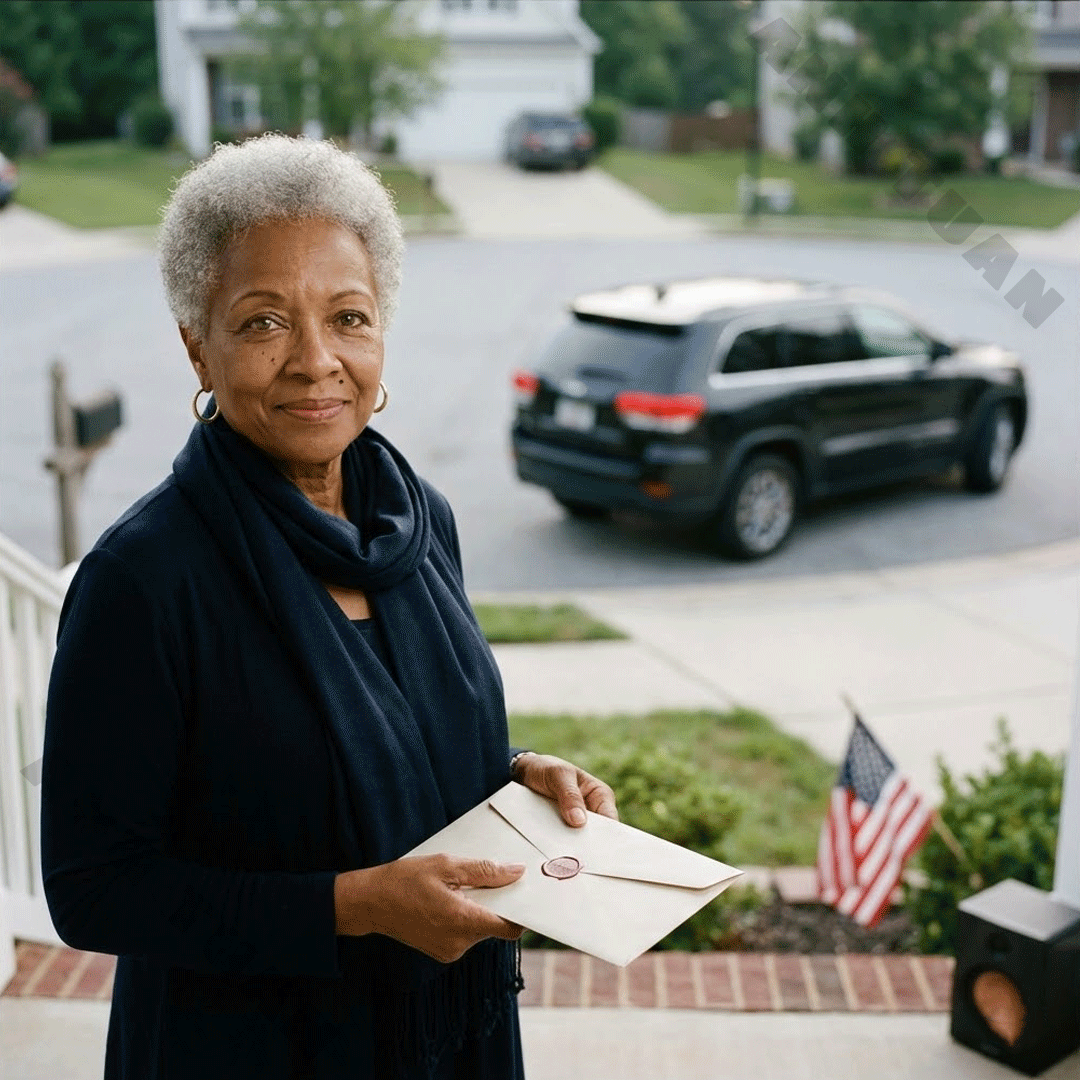

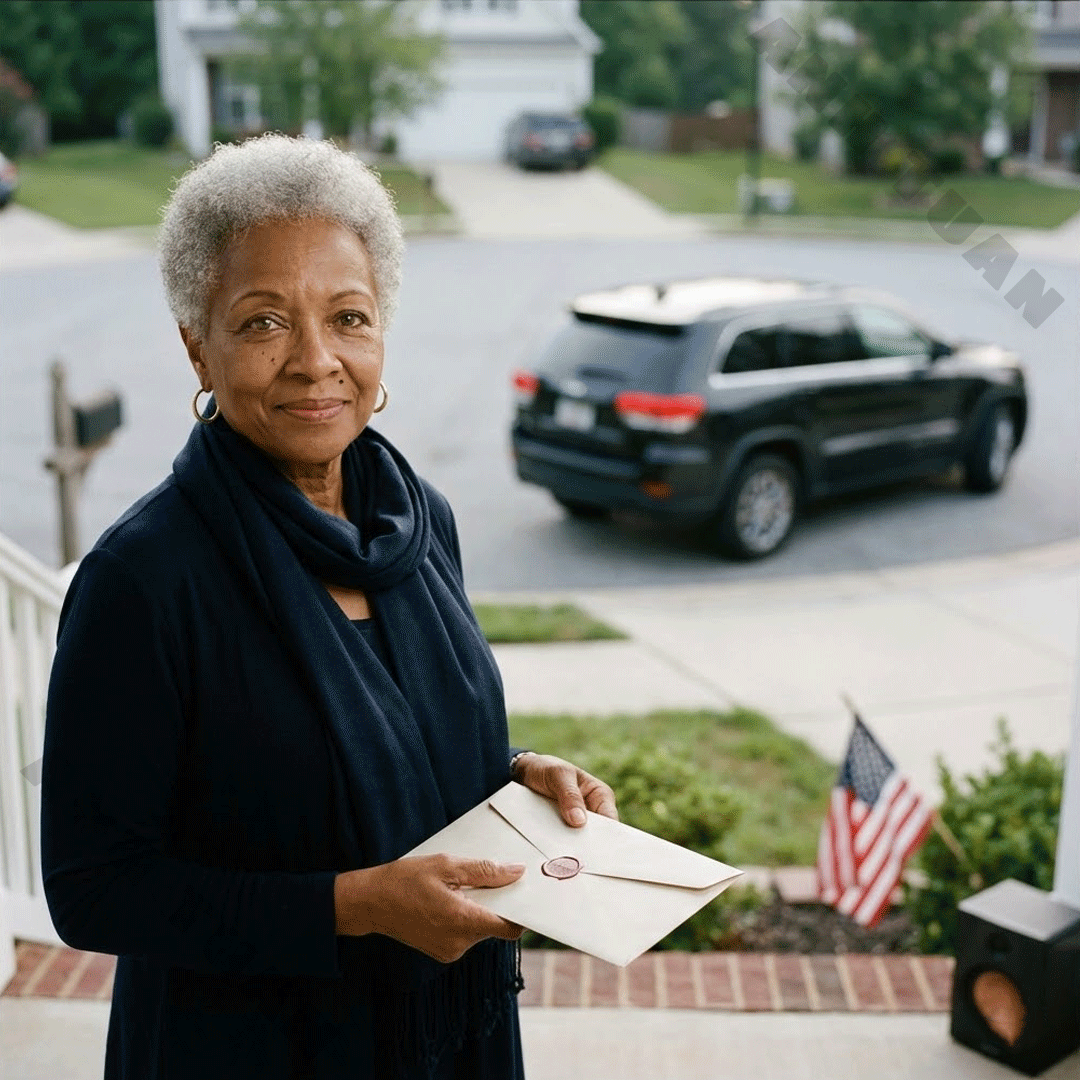

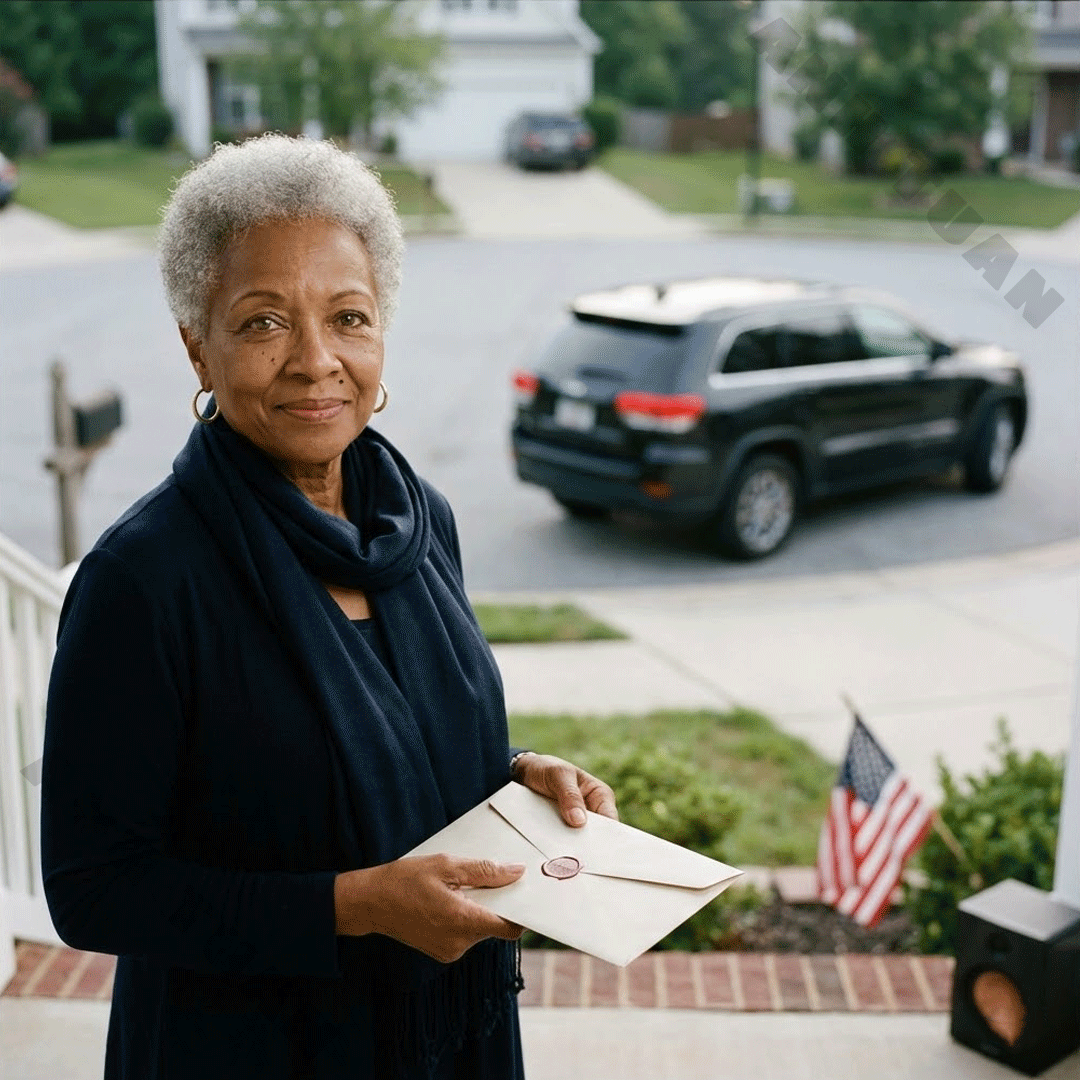

That’s what they said before driving off in their big black van, the one with the tinted windows and the third-row seats, laughing about Greek beaches and fresh seafood like those words couldn’t cut a person open. They tossed their suitcases into the back while I stood on my porch in slippers, waving the way you wave when you’ve learned that making a scene never gets you invited anywhere.

They didn’t see my face as they left. I didn’t say a word. I just waved, and I let the screen door hiss shut behind me like a quiet little punctuation mark.

But the next morning, I found their tickets sitting in my mailbox, still in the travel agency envelope, unstamped.

At first I thought it was junk mail. A coupon booklet. A catalog. Anything but that thick white envelope with the travel agency’s logo and the faint smell of printer ink. My name was typed neatly on the front, as if the universe had a sense of humor and was willing to commit to it.

I stood at the curb in my robe, the morning cold slipping up my ankles. The neighborhood was waking the way it always did, sprinklers ticking on, someone’s golden retriever barking at nothing, a distant leaf blower starting up like an angry bee.

I opened the envelope right there, because my hands were already shaking and it felt safer to see the wound than to carry it inside.

Plane tickets. Four of them. Departure in three days.

Athens.

Two adults, two children, seats together.

My name was nowhere. Of course it wasn’t.

I stared at the tickets for a full minute like they were someone else’s problem. Like maybe the mailman had mixed up addresses. Like maybe there was another Helen on this street and she was the one getting quietly erased.

Then I went inside, placed the envelope on my kitchen table, and made tea.

That’s what you do at my age when something punches you in the chest. You make tea and wait for your hands to stop trembling. You wait for your breathing to find its rhythm again. You wait for the hurt to turn into something you can carry without dropping it.

But my hands didn’t stop trembling. Not when I set the kettle down. Not when I reached for the mug with the chipped rim. Not when I looked at the tickets again and realized how easy it had been for them to imagine the trip without me.

I’d been many things in this house. A wife. A nurse. A secretary. A cook. The one who found lost shoes and patched ripped knees and wiped tears off small faces before school.

I’d fixed broken toys and broken hearts. I’d sat through flu seasons and teenage heartbreak and the long, slow decline of my husband, Paul, when the cancer turned him into a smaller version of the man who used to whistle while shaving.

Paul had been gone twenty years now. His photo still sat on the mantle, still young, still smiling, as if he was frozen in the era when my life made sense. If he were here, he wouldn’t have let this happen. Or maybe he would have seen it coming, the way men sometimes do, and he would have stood between me and the quiet humiliation of it.

For the last decade, I’d been just Grandma. Not Helen. Not Mom. Just the reliable background presence, muted and obedient, folded into their lives the way you fold a dish towel and tuck it away.

They thought I’d sit quietly and wait for updates. Photos of blue skies sent to the family chat. Messages like, “We miss you, wish you were here,” knowing full well they’d never intended to bring me.

I picked up my old address book, the one I kept out of habit even though everyone had numbers saved in phones now. Mine still had the travel agency scribbled in the corner in blue ink from years ago. Back when Paul was alive and trips meant road maps and diner coffee and stopping at state lines just to stretch your legs.

My fingers shook as I dialed.

The girl on the other end answered with the bright, practiced cheer of someone who hadn’t yet learned how heavy a voice can sound. “Good morning, Valley Travel. How can I help you?”

“I’d like to cancel these tickets,” I said.

There was a pause, the faint clicking of a keyboard. “May I have the confirmation number, ma’am?”

I read it off the paper, careful, steadying my voice the way you steady a glass you don’t want to spill.

More clicking. Another pause.

“Oh,” she said, surprised in a way that almost felt personal. “These are for Athens. They’re leaving in three days.”

“Yes,” I said. “Cancel them.”

A smaller silence. Then, gently, “Can I ask why, ma’am?”

“No,” I said. Not harsh, not dramatic. Just final. “Please cancel them.”

There was silence again, and I could hear her breathing, like she was trying to decide what kind of customer I was. Then her tone shifted, polite, almost cautious.

“Of course,” she said. “I’ll process that now.”

I listened to the keyboard clicks and imagined her eyes flicking between screens. A young woman with a headset, probably, hair in a ponytail, maybe a little bored until this moment. She didn’t know that on the other end of the line, a seventy-two-year-old woman was holding her whole pride together with one hand and a mug of tea with the other.

“All right,” she said. “They’ve been canceled. Here is your cancellation confirmation.”

I wrote down the number slowly, as if writing it made it real.

When I hung up, I didn’t feel triumphant. I didn’t feel mean. I felt calm in a way that startled me, like something inside me had finally stopped asking for permission.

Then I made another cup of tea and sat in the armchair where I used to rock my son to sleep, back when his small body fit against mine like a promise.

I looked around the living room as if I were seeing it for the first time. The couch with the faded spot on the armrest where Paul used to sit. The throw blanket Amelia had crocheted in middle school, uneven stitches and bright colors. The bookshelf full of things I’d read quietly at night after everyone else was asleep.

No debts. No one depending on me. Not anymore.

I had a little over twelve thousand dollars in my savings account. A few thousand more in bonds. A pension check that came like clockwork. The house was paid off. The car in the driveway was old but reliable.

And in the drawer where I kept important documents, my passport sat in a leather holder, still valid, like a door that had never fully closed.

I pulled it out and stared at it.

I thought about my hands, still trembling. I thought about Laura’s smile, David’s avoidance, the way they’d spoken to me like I was already halfway gone.

Then I opened my laptop and booked a flight.

Athens. One seat, aisle.

When the confirmation email landed in my inbox, my heart didn’t race the way it used to when I was young. It settled. Like it recognized something it had been waiting for.

Next, I called my neighbor Carol.

Carol lived two houses down, the kind of woman who always knew what the weather would do before the forecast did. In summer she wore big sunglasses and weeded her flower beds like it was a personal mission. In winter she brought soup to sick neighbors without ever making a speech about it.

When she answered, I could hear a daytime talk show in the background.

“Hey, hon,” she said. “Everything okay?”

“I need a favor,” I said. “Could you water my plants for a bit?”

“Sure,” Carol said without hesitation. “Going somewhere?”

“Just a little trip,” I said, and I let myself smile into the phone as if the words were a secret I was finally allowed to keep.

“Well,” she said, warmth in her voice, “good for you. I’ll keep an eye on things. You want me to bring in your mail too?”

“Yes,” I said. “That would be perfect.”

After I hung up, I moved through the house with a new kind of purpose. Not rushed. Not frantic. Just clear.

I packed one small suitcase. Comfy shoes. My best scarf. A paperback mystery novel I’d started and never finished. The navy-blue dress I hadn’t worn since Paul’s funeral.

Not because of sadness anymore, but because it made me look sharp, and I’d forgotten how to wear anything that made me feel that way. I added a simple string of pearls, the kind you don’t buy because you need them, but because they remind you that you once had a life outside of errands.

The night before my flight, I sat on the porch with a blanket over my knees. The street was quiet, porch lights glowing like small moons, distant traffic humming on the main road. A soft wind played with the ivy crawling up my porch column, and for a long time I just listened to the world continuing without needing anything from me.

I thought about what they would say when they realized.

Maybe they’d call. Maybe they wouldn’t.

I didn’t care, and the fact that I didn’t care felt like standing up after years of sitting too long.

The morning came gently. No dramatic sunrise, no thunder. Just pale light and the sound of a bird tapping at the feeder.

I locked my door. I left a note for Carol. I walked down the steps slowly, but with purpose, and I didn’t look back.

At the airport, the air smelled like coffee and floor cleaner and the tired perfume of strangers. Everything was glass and metal and announcements echoing off high ceilings. I hadn’t flown in nearly thirty years. Back then, airports still felt like excitement. Now they felt like a machine, moving human beings around like luggage.

The gate agent glanced at my passport, then at me, and smiled in that rehearsed way young people do when they see someone older traveling alone.

“Enjoy your flight, ma’am.”

I didn’t answer. I just walked on, one hand gripping the handle of my suitcase, the other holding my boarding pass like a shield. I moved through security, through the long hallway of shops selling things nobody truly needed, past families arguing about snacks, past business travelers staring into their phones like prayer.

Pretending you belong is half the battle. That’s something you learn when you’ve been quietly invisible for too long.

On the plane, I took my seat by the aisle and sat still while others stuffed bags into overhead bins. The seat beside me stayed empty until the last moment.

Then a young man in his mid-thirties, wedding ring, quiet eyes, slid into it with a sigh. He smelled faintly of aftershave and stress.

“Long trip?” he asked as we taxied.

“Long enough,” I said.

He smiled like he understood, then turned toward the window and left me alone, which I appreciated. There are kindnesses that look like conversation, and kindnesses that look like silence. I needed the second kind.

When the plane lifted, I gripped the armrest until my knuckles went pale. My stomach dropped, my ears popped, and for a moment I thought, This is ridiculous. What am I doing.

Then the clouds swallowed us and the ground fell away, and something in me unclenched.

I slept most of the flight. Not deep sleep, not peaceful. The kind of sleep that’s necessary. The kind that keeps grief from turning into rage.

When I woke, we were over the Mediterranean.

Endless blue.

I looked at the water and felt the moment land in my bones. I had really done it. I wasn’t here to sightsee. I wasn’t here for photos. I wasn’t here to prove anything to anyone.

I was here because they told me not to come.

At the airport in Athens, everything moved slower, and I did too. The heat was different, even inside, and the air felt like it carried dust older than my country.

I took a taxi to a modest little pension on a side street. Nothing fancy, but clean, the kind of place that smelled like soap and stone. The woman at the desk spoke English and called me madam, like the word still meant something.

Once in my room, I placed my suitcase by the wall and sat on the edge of the bed. The tiles were cool under my feet. The curtain fluttered slightly in the breeze from an open window.

I didn’t cry.

Grief doesn’t always look like tears. Sometimes it’s just sitting still and realizing how many birthdays and holidays you smiled through being unwanted. How many times you told yourself you didn’t mind. How many times you convinced your own heart to shrink so it would fit where they kept placing you.

That evening, I walked a few blocks, not far. I found a small bakery and ordered bread and olives, then sat at a table where nobody rushed me. I ate slowly without looking at my phone once.

Nobody was waiting on an update from me anyway.

The next morning, I woke early to soft light and distant footsteps in the hallway. I opened the shutters and let the morning in.

Then I did something I hadn’t done in years.

I put on lipstick, just a little. The shade I used to wear before everything in life became beige and apologetic.

At the front desk I asked for recommendations, not tourist spots.

“Somewhere quiet,” I said. “Somewhere that doesn’t feel like I have to rush.”

The young woman smiled like she understood more than she should for her age. She wrote something down on a scrap of paper.

“Anafiotika,” she said. “It’s old. Very peaceful.”

So I went.

White houses. Winding alleys. Cats sleeping in doorways. Flowers spilling out of chipped pots as if they had decided beauty was worth the effort even when the paint peeled. The air smelled like warm stone and bread and something faintly floral I couldn’t name.

I walked until my feet ached. Then I sat on a stone bench and just existed while young couples passed by, sun-happy and loud.

No one stared at me.

No one told me I was too old.

No one told me to just watch the house.

I thought of my granddaughter, Amelia, sixteen, always sending me pictures with ridiculous filters, her tongue out, her eyes too bright. I wondered what she’d say if she saw me here.

Probably laugh. Maybe roll her eyes. Maybe, if she was in a softer mood, she’d say something like, Grandma, you’re kind of iconic.

I reached into my bag and pulled out a postcard I’d bought earlier. I hadn’t planned to write, but my fingers moved on their own.

Dear Amelia,

Guess where I am. Greece. The sea is bluer than you can imagine. I hope you’re well.

Love,

Grandma.

I didn’t write to my son or his wife. They didn’t need to know where I was. Not yet. Not while the part of me that had spent decades being polite was still learning how to be quiet on purpose.

The post box was near a café. I dropped the card in and ordered coffee. I drank it slowly the way my mother used to in the mornings, back when I was a girl in a small American town and life still felt like it held more doors than walls.

That evening, back in my room, I realized I was humming.

An old tune Paul used to whistle while shaving. A tune I hadn’t thought of in years.

I wasn’t young. I wasn’t particularly brave. But I was finally somewhere I wanted to be, and that counted for something.

I didn’t plan on meeting anyone. That wasn’t the point.

But life has its own sense of timing, and it rarely consults you before setting something in motion.

It happened at breakfast two days after I arrived.

I was at a little table near the window, sipping coffee and buttering toast with more care than necessary. Across from me at the next table sat a woman about my age, silver hair swept into a no-nonsense bun, eyes sharp behind half-moon glasses perched low on her nose.

“You use too much butter,” she said, not unkindly.

I looked up, slightly amused. “Better than too little.”

She nodded once. “Fair.”

That was the beginning.

Her name was Rosalie, a retired school principal from Lyon, traveling alone like me. Widowed, she added casually, as if it were just another stamp in her passport. She carried herself with that dry, flinty confidence some women wear like good perfume, not overpowering, just quietly present.

We started walking together, not far, just morning strolls through quieter streets. I liked the way she noticed things. Not the postcard landmarks, but the details everyone else passed by. A broken shutter painted lilac. A dog asleep beside a statue. A cracked tile repaired with gold, like the city had decided flaws could be decorative.

She wasn’t trying to capture anything for social media. She just looked. Really looked.

At lunch, we sat under a vine-covered terrace sipping cold white wine. She talked about her students, the troublemakers she secretly liked most, the ones who needed a firm hand and a soft heart at the same time. I told her about my garden back home, how the tomatoes never cooperated no matter how gently I spoke to them.

“And your family?” she asked, as if it were just another ordinary question.

I paused, watching the light flicker through the leaves overhead. “They’re fine,” I said. “They just thought I was too old to travel.”

Rosalie’s eyes narrowed slightly. “They said that to you?”

I nodded.

She didn’t gasp. She didn’t offer pity. She just sipped her wine, then set the glass down carefully.

“You’re here,” she said. “So they were wrong.”

That night I couldn’t sleep.

I lay in bed staring at the ceiling, thinking about all the years I’d stayed in my lane. The birthday parties I cooked for but never sat down to enjoy. The trips I helped fund but was never invited on. How often I told myself, They’re just busy, or They need you here, as if my life was a tool they kept in a drawer.

The truth was, I wasn’t needed. Not really. Not beyond the caretaking, the meal prep, the dependable presence that made their lives easier.

The next morning, Rosalie knocked on my door.

She stood in the hallway with a map folded under her arm and a glint in her eye like a teenager about to skip class.

“Florence,” she said. “It’s not far. I’ve always wanted to see the Uffizi.”

I hesitated, because hesitation had been my default for so long it felt like a personality trait.

Rosalie lifted an eyebrow. “Well?”

I looked past her, down the corridor, at the bright rectangle of morning at the end of the hall. I thought about the canceled tickets. I thought about the way my hands had stopped shaking the moment I chose myself.

“Why not,” I said.

And just like that, we were two women over seventy buying one-way train seats like students on summer break.

We booked the tickets that afternoon, two women over seventy leaning over a little kiosk screen in the lobby like we were plotting something deliciously irresponsible. When the machine finally spat out our confirmations, Rosalie folded the papers with military neatness and tucked them into her purse.

“There,” she said. “Now it’s real.”

Over dinner that night, we laughed more than we meant to, the kind of laughter that isn’t about jokes so much as relief. I could feel something in me still tight, like an old muscle not used to moving. But Rosalie didn’t try to pry it open. She just talked about trains and shoes and the best way to avoid tourist crowds, as if she’d been waiting her whole life to do exactly this.

That evening, I turned my phone over on the bedside table and let it stay facedown like a closed eye. I thought about David and Laura somewhere back home, probably sitting on my couch with their feet up, the kids eating cereal out of bowls I’d washed and stacked. The thought should have made me angry.

Instead, it made me oddly calm.

The next morning, I woke to a message from Laura.

Did you check the garden? The sprinkler system’s been weird lately.

No hello. No How are you. No softness at all, as if my only role in their minds was still “the one who handles things.” I stared at the screen long enough to feel my jaw tighten, then I set the phone down without replying.

Rosalie met me downstairs with a small vase of daisies in her hands.

“For your room,” she said, as if giving flowers to a near-stranger was the most ordinary thing in the world.

“They’re lovely,” I said, and I meant it.

“Because,” she added with a little shrug, “you look like someone who appreciates flowers without needing a reason.”

I didn’t know how to answer that. So I smiled, and I carried the daisies upstairs like a gift I was still learning how to receive.

That night, I packed carefully, not because I was in a hurry, but because savoring has its own pace. I folded the navy dress with more tenderness than fabric deserves, wrapped the pearls in a soft cloth, rolled my shoes into a plastic bag the way I used to when Paul and I took road trips and tried to keep our lives from spilling everywhere.

Then I placed my phone in the drawer and turned it off.

No pings. No alerts.

For the first time in a long while, I didn’t feel like someone waiting to be included. I felt like someone moving forward, one step at a time.

The train to Florence left just after nine.

We sat side by side in a quiet car, our bags stored above us, a paper bag of croissants between us. Rosalie read a mystery novel in French, lips barely moving as her eyes traveled down the page. I stared out the window at a countryside that unrolled like a painting, soft and golden, stitched with vineyards and sleepy towns.

It reminded me of an old print Paul once brought home from a flea market outside Columbus, cheap frame, beautiful inside. He said it looked like somewhere he’d never been but somehow missed anyway. At the time I’d smiled and told him he was sentimental.

Now, watching the fields and stone farmhouses slip by, I understood him in a way I hadn’t when he was alive.

We didn’t talk much. That was Rosalie’s gift. She didn’t need to fill silence. She didn’t press questions into the soft places. When the train rocked gently around a curve, she looked up from her book and offered me the last croissant without a word.

I took it and smiled.

That was enough.

Florence greeted us with warm air and narrow streets that felt like they’d been carved by centuries of footsteps. Our hotel was old and charming, the kind of place where the elevator creaked and the keys were heavy brass with leather fobs that made you feel like you’d stepped into a different era.

Our room had a tiny balcony overlooking red roofs and laundry lines strung between buildings like quiet flags of ordinary life.

Rosalie dropped her bag onto the bed. “I want to see the Uffizi,” she declared, then narrowed her eyes like she was making a second promise. “And maybe something ridiculous and expensive I’ll never wear.”

We did both.

The museum was crowded, but worth every slow shuffle behind other bodies. Standing in front of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, I felt something loosen in me. Not awe exactly. Recognition. The sense that beauty isn’t always loud.

Sometimes it’s quiet and inevitable, and you don’t realize it’s moving you until you feel your throat tighten and you have to swallow hard, not to cry, but to make room for the feeling.

We walked for hours afterward, stopping at a café where a waiter flirted with Rosalie and she flirted right back with a kind of amused dignity I envied. She had a way of making herself feel young without pretending to be.

That night we ate at a small place on the other side of the river, far from the crowds. Pasta with butter and sage. Red wine in short glasses. Laughter that came easier than it had any right to.

“You’re different now,” Rosalie said softly after a while, watching me over the rim of her glass.

“How so?”

“You sit taller,” she said. “Less folded.”

I didn’t know how to respond, so I just nodded and let the words settle. Later, back in the room, I checked my phone out of habit.

Twenty-four missed calls.

Fourteen from Laura. The rest from David.

I didn’t listen to the voicemails. I just stared at the list of numbers and felt something unexpected: distance. Not cruelty. Not indifference. Just space, enough to breathe.

The next day, Rosalie slept in. I wandered alone through a quieter part of town, following my nose rather than a map. I found a shop with linen skirts and silver earrings, tried both, bought neither, and still felt satisfied, as if trying on a different version of myself was its own form of purchase.

In the afternoon we took a bus to Fiesole, up the hill away from the noise. We sat under trees and watched Florence from above, a spread of terracotta roofs and pale stone.

“This,” I said, not meaning the view exactly.

Rosalie nodded like she understood. “Yes,” she said simply. “This.”

When we got back to the hotel, there was another message from David.

Mom, did you cancel our vacation on purpose? We got to the airport and…

The message cut off there, as if he’d run out of words or courage.

I turned the phone off again.

That night, as we walked back beneath a streetlamp glow, Rosalie asked, “So, where next?”

I surprised myself by answering immediately.

“Lisbon,” I said. “I’ve always wanted to hear fado live.”

Rosalie grinned. “Then we go.”

Lisbon welcomed us like an old friend. Warm, slightly disheveled, full of music you didn’t need to understand to feel. The sidewalks shimmered from last night’s rain, and even the air seemed to hum with quiet defiance, like the city remembered something the rest of the world had forgotten.

We stayed in a guest house with blue shutters and tile walls. Our room had a tiny balcony overlooking a square where children kicked a ball between rusted benches, their laughter bouncing up toward us like sunlight.

That first evening, I stood at the railing a long time, watching the sun slip down behind the rooftops, listening to Portuguese voices below, soft and fast, like wind moving through leaves.

Rosalie wasn’t feeling well that day. Nothing dramatic, just a low fever and aching joints that made her shoulders slump.

“It’s nothing,” she said, waving me off. “I’ve been worse. Go out. See the city.”

I should have. Old habit told me to, the habit of leaving people behind because you think they’re fine, because you think that’s what independence looks like.

But I didn’t.

I brought her tea instead. I sat by her bed and read aloud from a book we’d bought in Florence, my voice slower than usual, letting the words fill the room the way soft light fills a corner.

She dozed off halfway through a paragraph, her face peaceful in a way I hadn’t seen in days. The quiet breathing, the simple care. It reminded me of Paul in the hospital at the end, when love became less about romance and more about small mercies.

I realized something then, and it startled me with its gentleness.

I’d spent my whole life looking after others. Children. Grandchildren. Paul. Even the dog, back when we had one, a stubborn beagle that howled at sirens and slept with its head on my foot.

But this, sitting beside Rosalie, pouring tea, checking her forehead, this didn’t feel like obligation.

It felt like choice.

That night, I cooked for us. Nothing fancy. Eggs, bread, tomatoes from a corner vendor who smiled like we were old acquaintances. We ate on the balcony wrapped in shawls, the city below us alive with a softness that made my chest ache in a good way.

Rosalie’s color was better. Her voice steadier.

“Thank you,” she said after we finished.

“For the eggs?”

“For not leaving,” she said quietly.

I didn’t know what to say, so I nodded and took another sip of tea like it could carry the words for me.

The next morning, I woke to the sound of fado drifting up from the square, haunting and melancholic, music that seems to come from somewhere older than sadness itself. A man was playing below, his voice cracking in places, but it didn’t matter. The song reached me anyway.

I stood on the balcony barefoot, arms crossed against the morning chill, and let the music settle into my bones.

By the time Rosalie was ready to go out, the city had fully woken. We walked slowly, her still recovering, me lost in thought. We passed a church with its doors wide open, incense curling into the street like a question.

I didn’t go in. I just watched a woman light a candle and kneel, palms pressed together like she was holding something fragile between them.

Back at the guest house, I turned my phone on.

Five new messages.

Laura again.

This isn’t funny, Helen.

Then David.

You’ve made your point.

Had I? I wasn’t even sure what point they thought I was making. I hadn’t spoken a word since they left me behind. I hadn’t argued. I hadn’t yelled.

All I’d done was stop staying where they placed me.

Rosalie watched me read. She didn’t ask. She just poured tea and handed me a cup, her fingers steady, her eyes kind without being soft.

That night, we found a fado bar tucked between two laundry alleys. No menu. No tourists with cameras. Just locals, clinking glasses, and one woman with a voice that sounded like rusted silk.

She sang about longing. About being left behind. About getting back up.

I sat with my eyes closed, heart strangely still. She wasn’t singing for me, but I understood every note anyway.

Sometime during the night, a letter appeared under our guest house door.

No stamp. No envelope. Just my name written in rushed familiar handwriting.

I knew it before I picked it up.

David.

I sat on the edge of the bed with the letter unopened in my lap. Rosalie busied herself with her scarf in the mirror, giving me the kind of privacy that is actually respect.

I unfolded the paper carefully.

It wasn’t long. Three short paragraphs written with the same cold courtesy David used when he filled out forms.

Mom, we don’t understand what you’re doing. The kids are confused. Amelia cried. We thought you were just upset, but this is something else. If you’re trying to punish us, you’ve made your point. Come home. Let’s talk.

Please,

David.

That was it.

No I’m sorry.

No acknowledgement that they had excluded me from a trip they planned with ease, without a second thought.

Just concern for how it looked now that I was gone, as if my absence embarrassed them more than their rejection had hurt me.

I folded the letter and placed it in the drawer beside my bed.

Rosalie turned, one eyebrow raised. “So,” she said, dry as dust and twice as sharp, “are we having breakfast, or are we mourning the weak penmanship of disappointing sons?”

I laughed, and the sound startled me with how real it was.

We ate in the courtyard that morning. Sunlight filtered through the vines above, and the smell of sweet bread and strong coffee softened something in me that had been rigid for too long. Rosalie chatted about tram routes and a tile museum she wanted to see.

I nodded, but my thoughts stayed with the letter, with the quiet that had followed my absence from their lives.

The truth was, I hadn’t left to punish anyone.

I’d left because I was done asking for a seat at a table that kept shrinking every year.

Birthdays had become text messages. Holidays were “too busy this year, maybe next.” And now even vacations, the joyful ones, the family ones, came with the quiet understanding that I was no longer included.

I hadn’t stopped being a mother or a grandmother.

They had simply stopped seeing me.

Later that day, I sat alone on a stone wall by the river. Boats drifted slowly. Pigeons argued over crumbs at my feet. My hands rested in my lap, still as the water.

I thought of Amelia, sixteen, all bright eyes and too much eyeliner, a girl who still had the courage to be dramatic in public. The last time we spoke she’d asked me how to fry an egg. She’d called me the egg whisperer, giggling like it was the funniest thing she’d ever said.

She didn’t know about the tickets. Didn’t know I’d canceled the whole trip. She probably thought they’d forgotten to invite me or that I’d said no.

I reached for my phone and typed a message before I could second-guess myself.

Sweetheart, I’m fine. I’m traveling. Not angry, not hiding. Just needed a bit of sky. Don’t worry. I love you.

I hit send, then exhaled as if I’d been holding my breath for a year.

Rosalie found me half an hour later carrying two small paper bags.

“Pastéis de nata,” she said, holding one up like a trophy. “You can’t leave Lisbon without trying these.”

We ate in silence, watching shadows lengthen. I could taste cinnamon and sugar and warm custard, and for a moment my life felt so simple it almost hurt.

That evening, the guest house manager approached us with a puzzled look.

“Mrs. Helen,” he said carefully, “your daughter-in-law called. She is worried. She asked me to tell you… the children miss you.”

I nodded. “Thank you.”

He hesitated, then asked, “Do you want to call her back?”

“No,” I said, and the word didn’t shake.

I slept deeply that night, the kind of sleep you get when you stop expecting to be needed and start choosing to be whole.

In the morning, Rosalie showed me two train schedules, one for Madrid, one for Seville.

“Your pick,” she said.

I looked out the window. The sky was cloudless. The street below smelled of roasted chestnuts and bus brakes and life in its unpolished form.

“Seville,” I said. “Let’s see what else they said I was too old for.”

Seville felt like fire in the bones.

Not just from the heat, though it pressed down on us like a warm hand, but from the life that pulsed in every alley, every open window, every late-night voice echoing across stone streets.

It wasn’t a city that asked permission to be seen. It simply was. Bold. Proud. Unapologetic.

We arrived in the late afternoon. Our hotel was tucked between a bakery and a small shoe shop that smelled of leather and dust. The room was modest, but the balcony overlooked a courtyard with orange trees, their scent mixing with the distant hum of a flamenco guitar.

Rosalie took one look around and declared, “This place demands earrings.”

She disappeared into the bathroom and emerged minutes later wearing silver hoops that danced when she moved her head.

I had none to match, but I pinned back my hair and put on lipstick. The same tube I’d started using in Athens. It was almost empty now, and for the first time in years, I considered buying another.

That evening, we went out without a plan. The streets were alive, not in the loud tourist way, but in the way old cities breathe after sunset. We followed the sound of clapping and found ourselves in a courtyard restaurant where a small group performed flamenco, not for tips, not for cameras, but for each other.

A woman danced, her face neither smiling nor posed. She was simply present, fully inside her own body without apology.

I couldn’t stop watching her.

Rosalie leaned in and whispered, “She’s older than we are.”

I looked closer. The dancer had to be in her mid-seventies at least. Her feet struck the floor with the force of a promise. The crowd applauded at the end.

I didn’t clap. I just sat there with my throat tight, heart too full.

The next day, we visited the Alcázar. Its walls told stories in tiles and arches. I walked those gardens as though I belonged there, and no one stopped me. No one called me dear. No one offered to take my arm like I was fragile.

And for once, I didn’t feel fragile.

That afternoon, we sat at a café under a striped awning. Rosalie sipped lemonade and read the news on her tablet. I watched people walk by, letting the day move around me.

That’s when I saw the family.

Four of them. Two parents, two teenagers. The father looked tired. The mother walked slightly ahead, phone in hand. The girl had headphones on. The boy carried a small plastic bag.

It should have been unremarkable, but the woman’s haircut, sharp and blonde, struck something in me. For a second, my breath caught. I saw Laura’s silhouette in that stranger and my chest tightened, not from hurt exactly, but from a strange, old reflex.

It passed.

Back at the hotel, there was a message from Amelia.

Grandma, where are you now? Your photo from Lisbon was amazing. I showed it to my art teacher. She said you have a really good eye. Can I call you soon?

I smiled, then frowned.

I hadn’t sent her a photo.

I opened my gallery. There it was. Me on the balcony in Lisbon, one arm resting on the iron rail, looking out at the street, not posing, not apologizing, just existing.

I didn’t remember Rosalie taking it. I didn’t even remember standing still that way.

But there I was.

I typed back.

Seville now. It’s hot and stubborn and full of beautiful noise. I’ll call you tomorrow. You’d love it here.

That night, I lay in bed and thought about all the places I’d never been because someone always had to stay behind and hold everything together. The times I’d said, You go ahead, I’ll be fine, even when I wasn’t.

The vacations I helped pay for but wasn’t invited on.

The weddings I helped plan but sat at the edge of.

But now here I was in Seville in a soft cotton nightgown I’d bought from a street vendor who called me la señora valiente, the brave lady. I let the distant music float through the window and promised myself something quietly.

Tomorrow, I would dance, not for anyone, just to remember I could.

It started with a call I didn’t answer.

Then another. And another.

By midmorning, my screen lit up again.

David.

Same name, same number, same silence behind it.

When I let it ring out, there had been twenty-six calls in two days. One voicemail after another. I didn’t listen to a single one.

I wasn’t angry anymore.

I was just done with asking to be heard.

Rosalie was already dressed when I stepped out of the bathroom. She wore a wide-brimmed straw hat and a linen dress that floated behind her when she moved.

“There’s a market by the river,” she said. “And I feel like haggling.”

We walked there slowly, sandals scraping against old stones, the sun licking the back of my neck like a mischievous child. The market was alive, not polished, not curated, real. Men shouting prices. Women laughing. Children darting between stalls with sticky fingers.

Something loosened in my chest, a thread pulled free from a knot I didn’t know I’d been carrying.

I bought a scarf, yellow, bright as marigolds. It wasn’t a color I usually wore, but it caught the light like it belonged in my life.

While Rosalie negotiated over a basket, I sat beneath a faded umbrella with a cold drink and checked my messages. I don’t know why. Habit, maybe. Hope, maybe. There was a voice memo, not from David this time, but from Amelia.

Her voice was soft, uncertain.

“Grandma… I don’t know if you’ll hear this, but I just wanted to say I miss you. Mom and Dad are kind of freaking out. They think you’re trying to prove something, but I don’t think so. I think you just got tired of being left behind. I would have been too.”

She swallowed, then added in a smaller voice, “Anyway, I hope you’re safe. You look happy in that photo. I’ve never seen you look like that. Just call me, okay? Even if it’s just for a minute.”

I listened to it twice, then again, and that last sentence cracked something open in me.

Even if it’s just for a minute.

I walked back to the hotel alone while Rosalie went looking for olives. I sat on the edge of the bed with the yellow scarf in my lap, fingers tracing the fabric as if it could steady me.

Then I picked up the phone and called.

Amelia answered on the second ring.

“Grandma.”

Her voice wavered. I could hear a kettle boiling somewhere, footsteps across tile, a door closing as she moved to a quieter place.

“I’m here, sweetheart,” I said.

“Oh my God,” she breathed, and the relief in her voice made my eyes sting. “Wait ”

The phone jostled. Then quiet.

“I was starting to think you’d gone totally rogue,” she said, trying to joke, but her voice trembled.

“Not rogue,” I said gently. “Just found something I’d forgotten I lost.”

“What?” she asked, and I could hear how carefully she was holding herself.

“Myself,” I said, and the word didn’t feel dramatic. It felt true.

She was quiet a moment.

“I get it,” she said softly. “I think I get it more than Mom and Dad do.”

We talked for fifteen minutes about school and her drawings and a boy she liked who didn’t like her back. Normal things. Precious things.

Then she asked carefully, “Are you coming back soon?”

“I don’t know yet,” I told her honestly.

“Can I see you when you do?”

“Of course,” I said. “Of course, baby.”

When we hung up, I felt lighter, not because everything was fixed, but because something true had passed between us. And real truth always clears the air, even if it doesn’t solve everything right away.

Rosalie returned with a triumphant look and a paper bag full of olives.

“Victory,” she declared.

We ate them on the balcony while the sunset burned the sky red.

“I think they’re starting to understand,” I said after a while, surprising myself with the words.

Rosalie chewed slowly, then nodded. “About time.”

That night, I didn’t sleep much, not from restlessness, but from something deeper, a shift. A new weight, not heavy, but solid, like finally finding the floor under your feet after drifting too long.

In the morning, I tied the yellow scarf neatly at my neck for no reason other than I could.

Lisbon had been soft and aching. Florence, graceful and slow. Seville had given me heat and thunder, shaken loose a part of me I hadn’t realized was still trapped in apology.

And now, with my scarf in place and my ticket in hand, we boarded the train to Granada.

Rosalie was humming.

She never hummed in the mornings.

“What’s the occasion?” I asked.

She raised an eyebrow. “We’re going to see the Alhambra,” she said. “I hum for architecture.”

I smiled, folded my hands in my lap, and watched the countryside blur by.

Granada was quieter than I expected. Not silent, just respectful, like the city knew what it held and didn’t need to shout about it. The streets were narrow, like whispers passed between buildings. The air carried the scent of oranges and stone.

We checked into a small inn run by a man who looked like someone’s tired uncle. Our room had a view of rooftops and laundry lines, the kind of view that tells the truth. Not curated. Not polished. Real.

That evening, Rosalie napped, and I sat alone on the terrace, the sky deepening into a blue that reminded me of late summer nights back home in Ohio when the fireflies came out and the world felt briefly magical.

I scrolled through my messages, not to see what they said, but to remind myself I could look and not react. It’s a strange kind of freedom, choosing silence on purpose instead of having it chosen for you.

One message caught my eye.

David.

Just one line.

Mom, did we lose you?

There was no anger in it. No guilt either. Just a note, a recognition maybe, the first crack in the story he’d been telling himself.

I didn’t respond.

Instead, I opened the notebook I’d bought in Lisbon and hadn’t written a single word in. The pages were blank in a way that felt almost accusatory.

Now, I began.

Things I’ve never said out loud.

I wasn’t always tired. I just got tired of not being seen.

Every time you called me old-fashioned, I swallowed a sentence I should have said.

I still remember you at five years old, handing me a rock you found in the yard and calling it precious.

It was the last time you gave me something just because.

I miss being called by my name.

I kept writing until my hand cramped. I didn’t cry. I didn’t need to. The truth was doing its quiet work.

In the morning, we climbed to the Alhambra.

The hill was steep, and my knees ached, the ache of old joints and long years. But I kept going, not to prove anything, just to see it for myself. I stopped once to breathe, palm pressed to the warm stone wall.

Rosalie looked back at me, eyes sharp. “Slow is fine,” she said. “Stopping is fine. Quitting is not.”

“I’m not quitting,” I said, and meant it.

At the top, the Alhambra opened like a secret. Arches and fountains and carvings so delicate they looked like lace made out of stone. It made me wonder how many hands had worked for years to create something this beautiful without being rushed.

How many people had stood in the same spot thinking, So this is what beauty looks like when no one hurries it.

Rosalie took a photo of me sitting on a bench framed by light and shadow.

“You look like someone who remembered something important,” she said.

“I have,” I replied. “I remembered I was never just someone who stayed behind.”

That night, back at the inn, Amelia sent me another voice message.

Her voice sounded tight.

“Grandma… I think Dad is starting to realize something’s really changed. He asked if I’d heard from you. I said yes, and he looked scared. Kind of like he knows he can’t just apologize with flowers and act like none of this happened.”

She hesitated, then said quietly, “I told him you’re not angry. You’re just finished. I hope that was okay.”

I didn’t type a long answer.

I sent her the photo Rosalie took that morning. Me at the top of the hill, hands on hips, the Alhambra behind me, face calm. No caption.

Amelia replied with a heart and nothing else, which was exactly enough.

I closed my phone, lay back on the bed, and stared at the ceiling fan turning slowly above me.

Tomorrow, Rosalie said, we’d head toward the coast.

She wanted to see the ocean again.

I said yes, not because I needed the view, but because I finally had space to want something again.

We took an early bus to Cádiz.

Rosalie claimed the sea air did wonders for her lungs and her posture. I thought she just liked how the wind tangled her hair and made her feel difficult to contain. The ride was long, the seats stiff, but I didn’t mind. I watched the landscape flatten and widen, olive groves turning into scrub, scrub turning into salt marshes, until finally the coast appeared wide and blue and breathing.

We found a guest house near the old port. The room smelled of salt and old wood. From the balcony, we could see fishing boats pulling in at dusk, nets trailing like tired promises.

I stood there a long time, one hand resting on the railing, the wind tugging at my sleeve.

That evening, we walked the beach.

The waves weren’t dramatic. Just steady. Persistent. The kind of persistence that lasts longer than anger ever could.

Rosalie picked up a piece of sea glass and tucked it into her pocket like a small, private treasure. I walked barefoot, letting cold water nip at my toes.

Nearby, an older couple held hands like teenagers. They didn’t speak. They just walked together, fingers locked, as if they’d finally reached a point in life where love didn’t need explanation.

I sat on a low rock and watched the sun dissolve into the horizon.

Somewhere behind me, Rosalie was humming again, the same tune from the train to Granada. It floated on the wind, mixed with gull cries, and for a moment I felt so alive it made me dizzy.

My phone buzzed in my pocket.

I didn’t move. Not for a long time.

Eventually, I pulled it out.

David again.

Please just let us hear your voice.

I stared at the screen until the words blurred.

Then I opened the voice memo app and pressed record.

I didn’t script it. I didn’t rehearse. I just spoke.

“David,” I said quietly, the sea breathing behind me, “I’m not angry, but I am changed. I spent most of my life waiting to be asked. To be needed. To be seen. And sometimes I was. But mostly, I was the background to your life.”

I paused, feeling the weight of honesty in my mouth.

“I don’t say this to make you feel guilty. I say it because it’s true. I love you. I always will. But I’m not coming back to the role you gave me.”

The wind tugged at my hair. The waves kept arriving and leaving like they had no interest in human drama.

“If you want me in your life,” I continued, “it won’t be as a backup plan or a babysitter or a name on the emergency contact form. It has to be as a person. A whole one. I hope you understand. Good night.”

I hit send.

The sea whispered something I couldn’t quite translate.

When I returned to the guest house, Rosalie was reading by the lamp.

She looked up. “You sent it.”

I nodded.

She closed her book. “How do you feel?”

“Like I finally said the thing I’ve been swallowing for twenty years,” I admitted.

Rosalie smiled, slow and satisfied. “About damn time.”

That night I dreamed of a hallway, endless, lined with closed doors. I walked barefoot, fingers brushing each handle.

One by one, the doors clicked open behind me.

I didn’t look back.

In the morning, there was no reply from David.

But there was a message from Amelia.

A photo.

She’d drawn something me on the beach, scarf around my neck, hair blown sideways. The caption read: She looks like she remembered who she was.

I stared at it for a long time, throat tight.

Then I turned to Rosalie. “Let’s go dancing tonight.”

Rosalie blinked. “Dancing?”

“Yes,” I said, and I could feel the word rise in me like a spark. “Dancing.”

She leaned back, amused. “Do your knees even allow that?”

I grinned. “They’ll learn.”

The bar wasn’t meant for us. Not really.

It pulsed with energy too young, too fast, too certain of its own novelty. A converted warehouse near the docks, dim lights, loud bass, a haze of perfume and sweat and history repurposed.

But we went anyway.

Rosalie wore her silver hoops again, hair loose, lipstick precise. I wore the yellow scarf, but not at my neck this time. I tied it in my hair like a ribbon I’d earned. My dress was simple, soft cotton, old but clean. It didn’t scream for attention.

It didn’t have to.

We found a table near the back. The floor was crowded. Young couples, middle-aged tourists, locals who danced like the rhythm owed them rent. A man in his sixties with a crooked mustache twirled a woman my age, and they both grinned like fools.

Something in me shifted.

“I’m going,” I said.

Rosalie looked up. “Where?”

“Out there,” I said, nodding toward the dance floor.

She blinked. “Alone?”

“Yes.”

I stood, adjusted the scarf in my hair, and walked onto the floor. I didn’t wait for a partner. I didn’t wait for permission. I just started moving.

At first, it felt strange, like borrowing someone else’s body. My limbs stiff, breath shallow, years clinging to me like dust. But the beat pulled me forward, and the years began to fall away, not disappearing, just loosening their grip.

I danced, not gracefully, not skillfully, but fully.

A young man passed by and smiled, not mockingly, genuinely. He offered a hand. I took it for a moment, spun once, laughed, then let go.

I didn’t need him to carry the rhythm.

I had my own.

Rosalie joined me after a while. We danced together like schoolgirls at a reunion awkward, breathless, gleeful. We stayed for hours, two women with sore joints and bright eyes, refusing to shrink.

When we finally returned to the guest house barefoot and flushed, we collapsed onto the bed like teenagers sneaking back in after curfew.

“That was irresponsible,” Rosalie said, gasping.

“I know,” I said, and I couldn’t stop smiling. “I loved it.”

“I know,” she echoed, and then she laughed too.

We lay there in silence catching our breath. My knees ached. My back would hate me tomorrow. But my chest felt wide open.

Before I fell asleep, I checked my phone.

Still no response from David.

I didn’t feel disappointed.

Because there was another message from Amelia.

Dad doesn’t know how to answer you. He keeps reading your message. He printed it. It’s on the kitchen table. He hasn’t touched it all day. Mom thinks you’ve lost your mind. I told her maybe you finally found it. I miss you. I’m proud of you. I don’t think I’ve ever said that before, but I am.

I stared at her words, simple and quiet and real, the kind that sticks to your ribs.

I typed back, hands steady.

I miss you too. Tell your father he doesn’t have to answer yet. Some truths take time to land.

Amelia responded with a single emoji: a little anchor.

It made me laugh.

I set the phone down and stared at the ceiling as the fan turned slowly overhead. I thought of the dance floor, of the moment I let go.

I hadn’t climbed a mountain or learned a new language or fallen in love.

But I had reclaimed something.

My joy.

And at seventy-two, that felt as radical as anything.

We left Cádiz at dawn.

Rosalie slept most of the ride, head against the window, arms crossed like a woman who’d known too many trains to bother with comfort. I didn’t sleep. I watched the light move across the fields, watched towns pass names I wouldn’t remember, places I’d never return to.

I wasn’t restless.

I was preparing.

Barcelona was our last stop. Neither of us said it out loud, but we knew. We’d seen enough cities to recognize when a journey is winding down, when momentum turns into something quieter, something settled.

We arrived in the afternoon and took a taxi to a quiet street near El Born. The hotel was small, the room plain, but the bed was soft and the windows opened wide to air that smelled like salt and traffic and something faintly sweet from a bakery down the block.

We unpacked in silence.

Later, we walked just enough to feel the city under our feet. I remembered Amelia once saying, Barcelona feels like it was built by someone who wanted to paint with buildings.

She wasn’t wrong.

Gaudí’s work peeked out from corners like mischief in stone. The colors were bold. The shapes impossible. I liked it more than I expected.

We had dinner at a café tucked between two bookstores. I ordered fish. Rosalie ordered soup. Neither of us finished our wine. The conversation was light weather, train times, shoes but underneath it ran a different current.

We both felt the end before it arrived.

That night, back at the hotel, I sat on the balcony with a shawl around my shoulders and my notebook in my lap.

The list was longer now.

Things I’ve never said out loud.

Page three.

I thought if I gave enough, they’d keep me close. But love bought by sacrifice is always the cheapest kind.

I didn’t mind getting older. I minded being dismissed.

It took me fifty years to realize silence isn’t always strength. Sometimes it’s just fear dressed in patience.

I don’t regret the mother I was. I regret who I disappeared to become her.

I closed the notebook and let my hands rest on it like it was something alive.

My phone buzzed.

Not David.

Not Amelia.

Laura.

Her message was longer than usual.

Helen, we’ve all been talking. David doesn’t know how to reach you anymore. He thinks anything he says will come out wrong. I told him sometimes listening matters more. We didn’t mean to leave you out. I know that doesn’t fix anything, but it’s the truth. We planned the trip thinking it would be easier for the kids. We told ourselves you’d be more comfortable at home. That was a lie.

We were afraid of your age. Not because of your limitations, but because it reminded us of our own.

We’re sorry. I’m sorry.

If you ever decide to come home, we’d like to start over. No expectations. Just you as you are.

I didn’t cry.

But I sat very still for a long time, as if any movement might spill something over the edge.

It wasn’t an apology that erased anything.

It was simply a beginning.

The next morning, Rosalie found me packing.

She raised an eyebrow. “Home eventually?”

“Yes,” I said.

“You sure?”

I nodded. “Yes.”

Rosalie sipped her tea with mock solemnity. “Well,” she said, “it’s about time you threw the last punch.”

I laughed. “It wasn’t a punch.”

“What was it then?”

I folded the yellow scarf carefully. “A door,” I said. “One that finally opened.”

Rosalie left two days later. We hugged at the station, long and quiet. Neither of us said goodbye. Just soon, because some friendships don’t need the drama of endings.

That night, alone in the room, I ordered one last glass of wine from the bar downstairs and sat by the window.

My scarf was on the table. My shoes by the door. The city outside was alive and indifferent, as it should be.

I didn’t feel finished.

I felt full.

Tomorrow, I would buy a ticket.

Not back to the house they told me to watch, but back to the life I finally chose to return to on my terms.

The airport the next day felt less like a goodbye and more like a pause.

I wasn’t leaving something behind. I was bringing something back, maybe, or what was left of her after decades of waiting in silence. I moved through the terminal with a steadiness that surprised me, as if my body had finally accepted that it was allowed to take up space. I didn’t shop. I didn’t browse magazines. I didn’t look around for distractions the way I used to when I didn’t want to feel my own thoughts.

On the plane, I didn’t watch a movie. I didn’t read. I just sat with the hum of the engine and the weight of everything I hadn’t said for years, watching the land below shrink, flatten, vanish. Every so often I touched the yellow scarf in my bag, not for comfort exactly, but to remind myself it was real. That I had gone. That I had come back with something I intended to keep.

When I landed, no one was waiting.

I hadn’t expected them to be. Even if they’d wanted to, they wouldn’t have known which version of me was getting off that plane. The air was thicker here, more familiar, the sky muted in that Midwestern way that makes even noon feel like it’s thinking about evening. It smelled like damp grass and overwatered hedges and the faint metallic bite of winter still hiding in the corners of January.

I took a cab.

The driver was young and chatty, asking if I’d been on vacation, if I’d visited family, if I’d seen “all the sights.” I gave short answers and stared out the window as the streets slid by like memories I hadn’t asked to remember. The bakery I used to take Amelia to when she was small, the one where she’d insisted powdered sugar made you look “like a ghost princess.” The park where David broke his arm falling from the monkey bars, his face turning pale before he cried because he didn’t want to look afraid. The pharmacy where Laura and I once stood side by side buying cough syrup and, later, a pregnancy test she slipped into her coat pocket like it was contraband.

They weren’t bad memories.

They were just far away now, like someone else’s handwriting in an old book.

My house was exactly as I left it.

Carol had watered the plants. The porch was clean. The key turned easily in the lock, and when I stepped inside, the familiar smell of my own life met me like a quiet handshake. The air was still. The rooms held their breath. I walked from one to the next, touching things the way you touch a place after being away too long, not because you doubt it’s real, but because you need to feel the proof.

The edge of the couch.

The chipped ceramic bowl on the table.

The photo of Paul by the fireplace, still smiling like he was about to say something funny and human.

Nothing had moved.

Everything had changed.

I didn’t unpack right away. I set my suitcase by the wall and made tea, because some rituals belong to you no matter what continent you’re on. I sat at the kitchen table with the window cracked open and let the quiet stretch until it stopped feeling like loneliness and started feeling like space.

My phone buzzed.

A message from Amelia.

Are you home?

I typed back.

Yes.

Ten minutes later.

Can I come by?

I didn’t hesitate.

Yes. Doors open.

She arrived in twenty.

No ceremony. No speech. She just walked in like she still belonged here, kicked off her shoes in the entryway the way she used to, and crossed the kitchen like the distance between us had never existed. She hugged me hard, the kind of hug that says I was scared without admitting it out loud. She smelled like shampoo and teenage perfume and the cold air outside.

“You’re really home,” she whispered into my shoulder.

“I’m really home,” I said.

She pulled back and studied me like a drawing she wasn’t finished with. Her hair was a little shorter. Her eyeliner was still dramatic, but her eyes held something steadier now, something that hadn’t been there before I left. She sat across from me, backpack still slung over one shoulder, and looked around the kitchen as if the room itself had a pulse.

“I like your house better when it’s awake,” she said softly.

“It’s been asleep,” I admitted.

She nodded like that made sense.

Then she said, “I liked your list.”

I blinked. “My list?”

She smiled, almost sheepish. “You left your notebook open in one of the photos,” she said. “I zoomed in. I read it. Well, part of it.”

My first instinct, the old one, was embarrassment. A small flare of panic, the feeling of being seen without preparing for it. But it passed quickly, replaced by something warmer and stranger.

I didn’t feel exposed.

I felt… known.

“I’m sorry,” Amelia added quickly, misreading my silence. “I didn’t mean to snoop. It just it felt important.”

“It was,” I said.

Her shoulders dropped, relief loosening her posture. “I’ve been making one too,” she said, reaching into her bag. “You inspired me.”

She pulled out a small spiral notebook and slid it across the table.

The first page read, in her messy, determined handwriting: Things I refuse to inherit quietly.

Below it, a list.

The belief that women outgrow desire.

The idea that aging is decline.

The habit of saying I’m fine when I’m not.

The silence that comes after someone tells you you’re too much.

The shame passed down like furniture.

I read each line slowly, as if tasting the truth of it.

When I looked up, Amelia was watching me, eyes bright but steady, daring me to dismiss it the way adults sometimes dismiss the deep things teenagers say to protect themselves from feeling small.

“You’re going to be all right,” I told her.

She swallowed. “Because you were?”

“Yes,” I said. “Because I was.”

We talked for hours after that, the way we hadn’t in years. She told me about art school, about a teacher who made her feel like her work mattered, about a boy she liked who didn’t like her back, and the way that truth felt like the end of the world and also, somehow, not the end of anything. We laughed about small things. We drifted into silence without panic. It felt like finding an old song and realizing you still know the words.

At one point, I reached across the table and took her hand.

“You know,” I said, “your father hasn’t called yet.”

Amelia looked down, thumb rubbing her own knuckle. “He’s scared,” she said.

“Of me?”

“Of what you’ve become,” she said quietly. “Of what he never let himself see before.”

I didn’t answer, because she was right, and we both knew it.

The doorbell rang.

Amelia looked up, something passing through her face like a shadow. “That’s them.”

I didn’t move.

“I’ll get it,” she said gently, and there was something protective in her voice that made my chest tighten.

I heard the door open. Muffled voices. Then a longer silence, the kind that fills a hallway when people don’t know what shape the next moment should take.

David stepped into the kitchen like it was sacred ground.

His face looked tired in a way that made him older than his years. He stood just inside the doorway, shoulders slightly hunched, hands empty like he didn’t trust himself to hold anything. His eyes flicked over me, the table, the kettle, the steam rising from the mug like proof I’d been living a life without him.

“I wanted to come alone,” he said, voice rough. “But Laura insisted.”

Laura appeared behind him, hands clasped in front of her. No makeup. No posture. Just real. It startled me more than anger would have.

“We don’t know how to start,” she said.

I stood slowly, not dramatic, not rushed, and felt my knees protest before they settled. I didn’t cross the room to hug them. I didn’t stay planted like a statue either. I simply stood in my own kitchen, in my own body, and let them see me.

“You already did,” I said. “You showed up.”

David took a step forward, then stopped, like he wasn’t sure what he was allowed.

“I didn’t want to lose you,” he said.

“You didn’t,” I replied. “You just stopped seeing me.”

He nodded once, small and helpless. “I’m sorry.”

Not grand. Not poetic. Just honest.

It was enough to begin.

I gestured toward the counter. “I made tea,” I said. “There’s still some in the pot.”

They sat.

Not like owners of the space, not like people asking forgiveness as if it were a favor I should grant quickly, but like people who had finally realized the seat at the table wasn’t theirs by default. It had to be earned.

We didn’t talk about everything. Not even close. You don’t rebuild a bridge by throwing all the bricks at once.

Laura asked about my trip, about the places, the food, the people. I gave her pieces, not the whole. She didn’t deserve the whole yet. She listened in a way I hadn’t seen before, her eyes less certain, her questions less performative.

David mostly watched me. He watched the way I held my mug. The way I didn’t rush to smooth out awkwardness. The way I let silence sit between us without apologizing for it.

They stayed an hour, maybe less.

Enough time for awkward sips of tea, too many pauses, and the quiet work of building a new shape between us. I didn’t rush it. I didn’t soften the rough parts. I let them feel the quiet I’d lived in for years, let them sit in it a while, let it do its work.

When they stood to leave, Laura hesitated near the door, as if she wanted to touch my arm and didn’t trust herself.

“Thank you,” she said.

“For what?” I asked, not cruel, just honest.

“For… letting us be here,” she said, and her voice cracked the smallest bit.

I nodded. “It’s my house,” I said. “It’s my life.”

David lingered on the porch after Laura stepped down the steps.

“Can I ” he started, then stopped, and for a moment he looked like the boy he used to be, the one who brought me dandelions and insisted they were “gold flowers.”

He swallowed.

“Do you want to come for dinner sometime?” he asked. “No big gathering. Just us. You and me.”

I didn’t say yes.

I didn’t say no.

I let the invitation hang in the air the way truth hangs when it’s new.

“We’ll see,” I said.

He exhaled, relieved by the possibility.

After they were gone, the house was quiet again, but not the brittle kind that cracks when you breathe too loudly. This was a softer hush. A pause before a new line begins.

That night, I sat on the porch with a blanket across my lap and the notebook open on my knees. The jasmine by the steps had started to bloom, and the smell carried on the cool air like something gentle insisting on its own existence.

I turned to a fresh page and wrote:

Things I know now.

People don’t notice your silence until it costs them something.

Leaving isn’t the same as running away.

You can still start over at seventy-two.

Some doors don’t need to be slammed, just closed softly but firmly.

Your voice isn’t gone. It’s waiting for you to stop asking for permission.

I tapped the pen against the paper, thinking of David’s face, Laura’s bare honesty, Amelia’s steady eyes.

Then I added:

Forgiveness isn’t for them. It’s for your own breath.

I closed the notebook and sat with my hands on it, feeling my pulse slow into something calm.

Amelia came by the next afternoon.

No warning. No reason. She walked in, kicked off her shoes, and flopped onto the couch like she was reclaiming a habit.

“I made a decision,” she announced.

“Oh?” I said, lifting an eyebrow.

“I’m applying to the program in Berlin,” she said, voice fast, trying to outrun her own fear. “I know it’s far. And Mom’s already freaking out, but I need to do this. I need to go.”

I looked at her, really looked, at the nervous steadiness in her face, the way she was bracing for me to say something cautious, something small, something that would make her stay.

“You should,” I said simply.

Amelia blinked. “Really?”

“Don’t wait for permission,” I told her. “You’ll miss your life.”

Her mouth curled into a slow, wide smile, and some of the tension in her shoulders dissolved.

“I knew you’d understand,” she said, and she sounded like she was talking to someone she’d been waiting for.

She stayed for hours. We made soup. We talked about books. She asked about Rosalie and laughed when I told her we danced until our legs gave out.

“You’re kind of a legend,” she teased.

“No,” I said, stirring the pot. “I’m just finally myself.”

Before she left, she handed me a small envelope.

Inside was a drawing, the beach in Cádiz, but with a new figure standing at the water’s edge. Me, arms open, head tilted toward the sea, scarf in my hair like a bright defiance.

At the bottom she’d written: She didn’t come back the same, and that was the point.

“I’m going to get it framed,” she said, shrugging like it wasn’t a big deal, like she wasn’t giving me a piece of myself back.

After she left, I placed the drawing beside Paul’s photo on the mantle.

He would have understood.

The next morning, a letter arrived.

Real paper. Blue ink. David’s handwriting.

I stood at the counter with the envelope in my hands for a long time before opening it, because some things deserve to be approached slowly.

Inside, he’d written:

Mom, thank you for the tea. Thank you for letting us sit in the silence. I see it now. I don’t expect to be forgiven, but I’d like to try. Not to erase anything, but to build something better, if you’re willing.

No declarations. No promises. Just a man learning how to speak differently to the woman who raised him.

I folded the letter and didn’t reply right away.

Not because I wanted to punish him. Not because I didn’t care. But because some silences aren’t meant to be filled. They’re meant to be honored.

Days passed.

Then a week.

I watered my own plants. I cooked for myself. I walked in the mornings, not as exercise exactly, but as a way to feel the shape of my life without anyone else’s needs pressing into it. I noticed things I hadn’t noticed when my days belonged to other people. The way the light fell across the kitchen tiles at nine a.m. The sound of wind moving through the bare branches in the front yard. The small satisfaction of doing something, then stopping, without feeling guilty.

The shape of my life was good.

Not loud. Not dramatic. Steady. Dignified. Mine.

A postcard arrived from Rosalie.

On the front was a sketch of Marseille’s harbor, all pale blue water and boats like little commas. On the back, her handwriting slanted and confident.

They still think I’m a widow with a secret inheritance, she wrote. Let them.

Then, beneath it, a tiny doodle: two women dancing in a bar, one with a yellow scarf, arms lifted like she had nowhere left to hide.

I laughed out loud in my kitchen, alone and delighted, and that laughter felt like proof I hadn’t imagined the whole thing.

I framed the postcard and put it by the kitchen window.

Then, one morning, I called David.

He answered on the second ring, voice cautious like he was afraid it would be a dream.

“Mom?”

“Sunday,” I said. “Five o’clock. I’ll bring dessert.”

There was a pause, then his exhale, the sound of someone realizing a door had opened and he didn’t want to slam it by moving too fast.

“Okay,” he said softly. “Okay. We’ll be here.”

When I arrived at their house on Sunday, Laura opened the door.

She didn’t smile too quickly. She didn’t reach for a hug. She just stepped aside and said, “Come in,” the way you say it when you mean it and you’re still learning how to mean it without performing.

I walked through their rooms like a guest, not like someone who’d once been here every week, folding laundry, wiping counters, holding the baby while Laura showered.

The walls had new art. The furniture had been rearranged. Even the air felt different, like a house that had been lived in without needing me to make it run. I wasn’t hurt. They’d kept living.

So had I.

Amelia was already at the table. She stood, kissed my cheek, and whispered conspiratorially, “I made salad. Don’t tell Mom if it’s bad.”

I sat down.

Dinner was fine, civil, a little stilted. David asked questions. Laura offered seconds. Amelia made jokes that landed like soft pillows, easing tension without pretending it wasn’t there.

I answered simply. I listened more than I spoke. I watched David’s eyes flick toward me like someone checking for cracks in a wall.

Toward the end, he cleared his throat.

“I… uh,” he started, then stopped and tried again. “I read your notebook.”

I looked at him. “What notebook?”

He swallowed. “The one on the counter in the photo,” he said. “Amelia let me read some of it.”

Amelia’s eyes widened slightly, but she didn’t look ashamed. She looked… certain. Like she’d made a choice and stood by it.

“You showed him,” I said, keeping my voice calm.

“I did,” Amelia said. “Because it was important.”

David’s hands tightened around his fork. “I saw what you weren’t saying,” he admitted. “And it hurt.”

“Good,” I said.

His head jerked up, startled.

“Good,” I repeated, steady as stone. “Because it means you finally heard me.”

He nodded slowly. “I did.”

Laura cleared her throat, gaze fixed on her plate as if looking at me might make her cry. “We’ve talked about things,” she said. “A lot. And we want to… we want to do better.”

“I’m not here for promises,” I told them. “I’m here to see if you’re learning.”

They both nodded, and that nod was worth more than any dramatic speech.

I brought out the dessert. Lemon tart, not too sweet, sharp enough to wake the mouth. We ate in a quiet that wasn’t uncomfortable, just honest, the kind you share when you’re finally learning how to hold each other without dropping the truth.

Then Amelia set her fork down.

“I want to read something,” she said.

She pulled a folded page from her pocket, hands trembling just slightly, and unfolded it like a flag.

Her voice shook at first, then steadied.

“Things I want to remember,” she read. “My grandma taught me that disappearing quietly is a slow kind of death. That staying soft is not the same as staying silent. That women don’t owe their energy to the comfort of others. That loving someone doesn’t mean becoming small for them. That it’s okay to outgrow your place at the table and demand a new one.”

No one spoke for a long time.

Laura stood first, not to make a scene, but to give herself something to do. She began clearing dishes. David helped. Amelia poured more tea. I sat back with my hands in my lap, letting the moment be what it was.

Not perfect.

Not fixed.

But real.

When I left, David walked me to the door.

He hesitated before speaking, the porch light casting soft shadows on his face.

“I know it’ll take time,” he said.

“I have time,” I answered.

Then I reached into my bag and pulled out a thin envelope.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“A copy of the tickets,” I said. “The ones I canceled.”

His fingers tightened around the envelope like it was heavier than paper.

“I kept them,” I said, not out of spite, but out of truth. “So we don’t forget how easy it was to erase me.”

He didn’t open it. He just nodded and tucked it into his pocket carefully, like it was something fragile.

We didn’t hug.

But we stood close, the way people stand when they might one day understand each other without needing to explain every bruise.

At home, I undressed slowly.