Three successful older siblings had spent so many years looking down on their youngest brother that the habit had hardened into something automatic, like breathing. It showed up in the way their eyes skimmed past him at family gatherings, in the way compliments were saved for one another and silence was reserved for him, in the way his name was said like a sigh when they had to say it at all. In their minds, he came from a farming background, which meant he belonged somewhere else, out past the paved roads and bright storefronts, where mud clung to boots and the world moved at the speed of weather.

They were wrong, and deep down they had always been wrong, but that truth was the kind of thing people only recognize when it is placed in their hands and they cannot drop it.

It was late summer in the Central Valley, the kind of afternoon when heat shimmers above asphalt and the sky looks bleached at the edges. The Reyes family home sat just outside a small town that had grown around agriculture and ambition, a place where you could still smell cut hay if the wind turned, but you could also see new rooftops marching across former fields. An American flag hung from the porch, sun-faded and stubborn, and the gravel driveway crunched under tires like a warning.

They had come because their mother had asked them to come. She had said it was important, said it in that tone that made grown children feel ten years old again, even if they drove expensive cars and had degrees framed in mahogany. There was supposed to be a lawyer involved, too, and when the word “will” floated into the air, it changed the shape of everyone’s attention. People became quicker with smiles and tighter with patience, like birds that had spotted a seed and were pretending they had not.

The youngest son, Ricky, arrived first.

He came rolling down the driveway in a brand-new Ford, big and glossy, with a dealer plate still in the back window, the kind of vehicle that announced itself before the engine even cut off. In town, people were used to seeing F-150s and dusty work trucks, but Ricky’s SUV looked like it had never met a dirt road in its life. He parked as if he owned the place, backed in cleanly, checked his reflection in the side mirror, and stepped out with that casual confidence that came from believing he had earned everything he had.

He was an engineer, and he carried that like a badge. Not the quiet kind, either, the kind that earns respect by doing, but the kind that expects respect simply because it exists. He smoothed his shirt, adjusted his watch, and walked toward the house with a grin that seemed to say, Just wait till you see me now.

A little while later, Sheila pulled up.

She drove a Fortuner that looked freshly detailed, windows tinted dark, tires shining. The vehicle was a statement as much as a mode of transportation, and Sheila, a doctor, knew how to make statements. She moved like she had places to be even when she was standing still, hair perfect, nails clean, a scent following her that did not belong anywhere near a kitchen full of frying onions.

After that came Ben, the accountant, behind the wheel of a Honda Civic that was practical but still nice enough to make a point. Ben was always like that. He liked to appear modest, but only in ways that still allowed him to win. His car was the kind of choice that said, I could have bought something flashier, but I’m smarter than that, which was just another way of showing off.

In the garage, with the shade offering a little relief from the harsh afternoon sun, they fell into the rhythm they knew best.

It started lightly, the way a fire starts with paper before it reaches the logs. A laugh here, a compliment there, voices bouncing off the concrete walls.

“Wow, Ricky!” Sheila said, her eyes sweeping over the SUV with approval.

“Another new car?” she added, like she could not decide whether to be impressed or offended by the fact that he might be pulling ahead.

“Of course,” Ricky replied, the grin widening. “I’m a Project Manager now.”

He said it with emphasis, letting the title land like a weight on the air, waiting for it to be recognized. Then he turned it back toward her, because that was how they played, tossing praise around like a private currency.

“And you too, Doctor,” he said, nodding at her vehicle. “Your car is shining.”

Sheila laughed, the sound bright and confident.

Ben leaned against his Civic, arms folded, watching them with an expression that suggested he had already calculated the value of everything in the driveway. He did not interrupt, not yet. He let them have their moment because he believed his moment would come, and because he enjoyed the comfort of being surrounded by people who spoke his language of success.

They laughed proudly about everything they had achieved, their voices rising and falling with the ease of people who had told the same story to themselves for years. Scholarships, internships, promotions, titles, credentials. The world had rewarded them, and they believed the reward proved they were better.

They did not notice, at first, how quiet the house was.

Their mother was inside, moving through the kitchen with the careful energy of someone trying to keep her hands busy so her heart would not break open. She had been cooking since morning, the scent of garlic and simmering broth filling the rooms. On the wall above the stove hung a small framed photo of their father, Don Teodoro Reyes, his face serious, his posture upright, as if even in memory he refused to slouch.

Their father had built something here, and he had done it in a way that never needed applause. He had worked the land back when it was only land, before the new subdivision, before the university, before the mall that now lit up the horizon at night. He had believed in providing, in keeping the family together, in making sure his children had choices he never did. When he had passed away, the house had felt too large and too quiet, like a barn after the animals were sold.

Today, though, the house was loud again, filled with footsteps and voices, and yet something still felt off, like a song playing in the wrong key.

In the middle of their chatter, the oldest brother arrived.

Kuya Carding.

He did not come in a car.

The first sign of him was the sound, a low mechanical rumble that did not match anything in the driveway. It was not a sleek engine. It was heavier, slower, a sound that belonged to work. The three siblings turned their heads, expecting maybe a contractor or a neighbor, and then they saw it.

An old farm tractor, paint dulled by sun and years, tires thick with dried earth, rolling up the gravel like it had every right to be there. Dust rose behind it in a soft cloud, caught in the light. Carding sat high on the seat, hands steady on the wheel, posture relaxed, as if the tractor was not an embarrassment but simply the way he moved through the world.

He wore a faded shirt that had seen too many wash cycles to hold its color, a straw hat pulled low against the sun, and boots caked with mud. There was sweat at his temples, and his skin looked darker than theirs, not by birth but by exposure. He looked like someone who had been outside all day, because he had. He looked like someone who carried real weight, the kind that did not show up on a résumé.

Ricky’s face tightened first, like a reflex.

“For heaven’s sake, Kuya!” he blurted out, loud enough for the words to hit the garage walls and bounce.

Carding shut off the tractor and climbed down carefully, as if he had all the time in the world. He smiled, and the smile was not defensive. It was gentle, almost amused, like he had expected this greeting and accepted it long ago.

“This is a family gathering, not the rice fields,” Ricky continued, heat rising in his voice. “Why are you showing up like that? You’re going to dirty up the whole house!”

Carding’s smile held. He reached up, adjusted his hat, and wiped sweat from his face with the back of his hand. His palm left a faint smear, like a reminder of where he had been.

“Sorry,” he said, and his voice was calm, almost cheerful. “I came straight from the harvest. I didn’t want to waste time going back to change.”

Sheila rolled her eyes so dramatically it was almost a performance.

“Good thing we studied,” she said, glancing at Ben as if inviting him to join the chorus. “Thanks to scholarships, we didn’t end up farmers like you. No progress at all.”

Ben let out a small laugh, the kind that sounded polite but carried a knife inside it.

“Exactly,” he added. “Look at us. Cars, degrees, success. And you still smell like dirt. What a shame.”

There were a dozen ways Carding could have answered. He could have snapped, could have reminded them who he was, could have demanded respect. He could have done what proud men often do when they are cornered, which is to make the corner smaller for everyone else.

He did none of that.

Carding didn’t answer.

He simply picked up a bag from the tractor, a sack of something heavy that thumped softly when he set it down, and walked toward the house. He stepped carefully on the porch, as if he were trying not to bring the outside in, even though the outside was already inside him. When he passed them, he nodded once, like a greeting and an apology wrapped together.

The three siblings watched him go, their expressions a mix of annoyance and superiority, and beneath that, something else they would not admit. Discomfort, maybe. Because Carding’s calm made their cruelty look uglier, and nobody likes a mirror that shows too much.

Inside, the kitchen was warmer, filled with steam and the low bubbling of pots. Their mother stood at the counter, hands moving quickly, eyes tired but alert. When she saw Carding, her face softened in a way it had not softened for the others. It was not favoritism. It was recognition.

Carding moved to her side without being asked. He washed his hands at the sink, scrubbing the dirt out from under his nails, and then he began to help. He chopped vegetables with practiced ease. He lifted heavy pots without complaint. He listened when his mother muttered about how the onions had been too strong this season, about how the grocery store had raised prices again, about how the weather had been strange.

He did it quietly, enduring the insults like a man who had endured worse, like a man who did not need to defend himself because he was not living for their approval.

In the living room, the others sprawled on furniture as if the house belonged to them more than to the brother who actually maintained the land around it. Ricky wandered from room to room, pointing out small things that needed updating. Sheila checked her phone, responding to messages, letting the glow of the screen paint her face. Ben asked about the lawyer again, as if the lawyer might walk in with a check.

The conversation kept circling back to money, to property values, to who deserved what, though they did it with the careful language people use when they want to sound respectable while being greedy.

Their mother called them to the table when the food was ready.

They sat down with the comfort of familiarity, plates filling quickly, forks clinking. There were dishes from their childhood, recipes their father had loved, flavors that should have softened them, reminded them of simpler days when they had all been hungry together and nobody had yet learned to measure worth in car models.

But pride has a way of ruining appetite.

The three professionals ate and talked and laughed, and their laughter carried that same bright edge as before, as if they were still standing in the garage admiring their own reflections. They spoke about work, about clients, about projects, about hospital politics, about taxes and investments. Their words were full of accomplishment and distance.

Carding ate more slowly.

He listened more than he spoke, eyes occasionally drifting to his mother, checking if she needed water, if she needed help, if she needed anything. Every now and then he stood to refill someone’s glass without being asked. He cleared plates as they emptied. He moved around the room like he belonged there because he did, even if they refused to see it.

At one point Ricky leaned back, satisfied, and looked at Carding with a smirk that had been shaped by years of believing he was the smartest person in the room.

“So, Kuya,” he said, loud enough to pull attention, “how’s life out there? Still talking to your crops like they’re your coworkers?”

Sheila laughed, and Ben followed, the sound joining like a practiced harmony.

Carding lifted his eyes, and for a moment the room shifted. There was something in his gaze that was not anger, not shame, but a kind of patience that felt heavier than both. He set his fork down carefully, as if he did not want to make noise.

“It’s good,” he said simply. “The harvest is strong.”

“Strong,” Ben repeated, tasting the word like it was a joke. “That’s nice. Meanwhile, some of us have real responsibilities.”

Their mother’s hand tightened around her spoon. She did not look up right away, but her shoulders rose slightly, like she was holding back words that would scorch the air. When she finally spoke, her voice was calm, though it trembled at the edges.

“Eat,” she said. “Just eat.”

The command landed softly, but it was an order. For a few minutes, the table quieted. Forks scraped plates. The ceiling fan hummed. Outside, a dog barked once and then stopped, like even the dog was listening.

Then the noise came.

A distant wail at first, thin and rising, then louder as it approached. A police siren, unmistakable, cutting through the afternoon in a way that made everyone freeze with a fork halfway to their mouth.

Ricky’s head snapped toward the window.

“What’s that?” Sheila asked, her voice suddenly smaller.

Ben stood, napkin falling from his lap.

Carding did not move right away, but his eyes shifted toward the front of the house, focused, alert, as if he recognized the sound not as danger but as arrival.

The siren grew louder, then faded, then returned again, joined by the low rumble of multiple engines.

They all moved toward the front windows.

Through the thin curtains, they saw it. A convoy of black SUVs turning onto the road, glossy and dark, moving with purpose. Gravel kicked up behind them. Sunlight flashed off windshields. The kind of vehicles that did not come to a house like this unless something serious was happening.

The first SUV stopped in front of the porch. Then another. Then another.

Ricky swallowed hard.

“It’s the Mayor,” he whispered, voice tight with sudden excitement. “Behave yourselves. This could help my business.”

He straightened his shirt as if success could be ironed into him in real time. Sheila smoothed her hair and stepped forward, already rehearsing her smile, because she knew how to greet power. Ben adjusted his posture, eager not to be overlooked.

The front doors opened outside.

They could see silhouettes moving, purposeful steps, the flash of badges on belts, the subtle presence of bodyguards. Someone in a crisp suit climbed out, and even from behind glass, the authority was obvious.

Sheila inhaled, then walked toward the porch as the knocking started, confident, practiced, ready to introduce herself into opportunity.

She did not yet know she was about to be walked past like she was furniture.

And the room, still warm with food and old grudges, was about to go silent in a way none of them would forget.

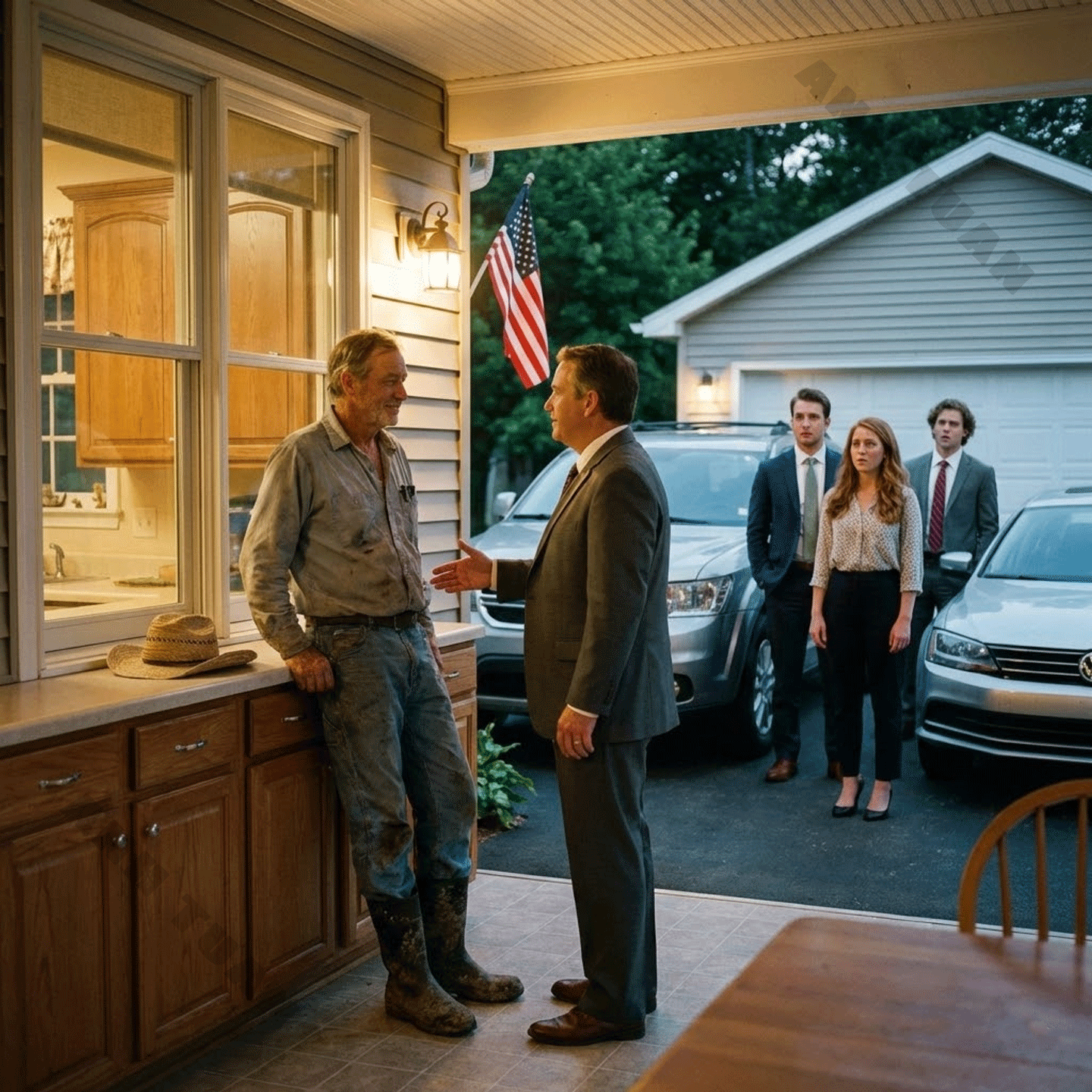

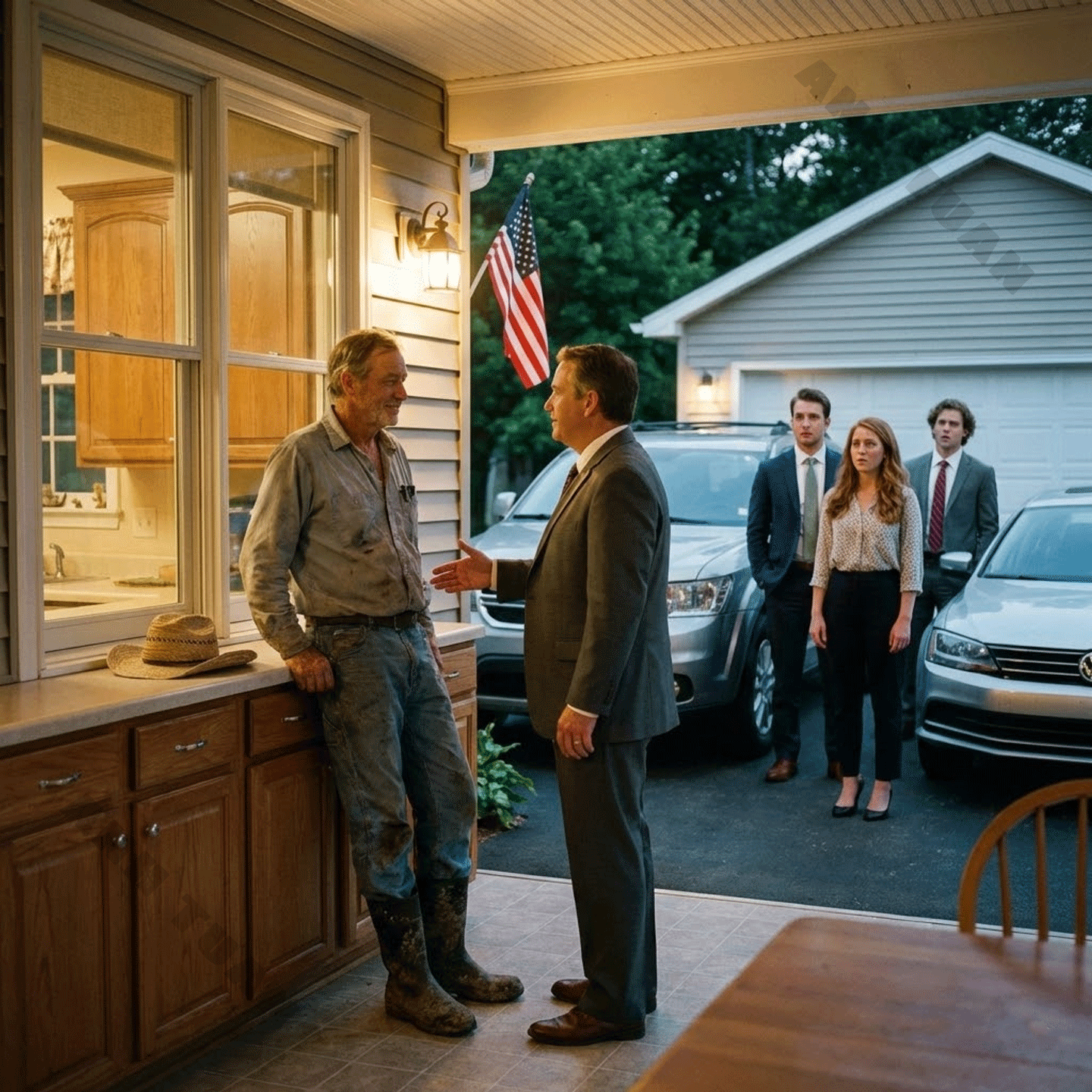

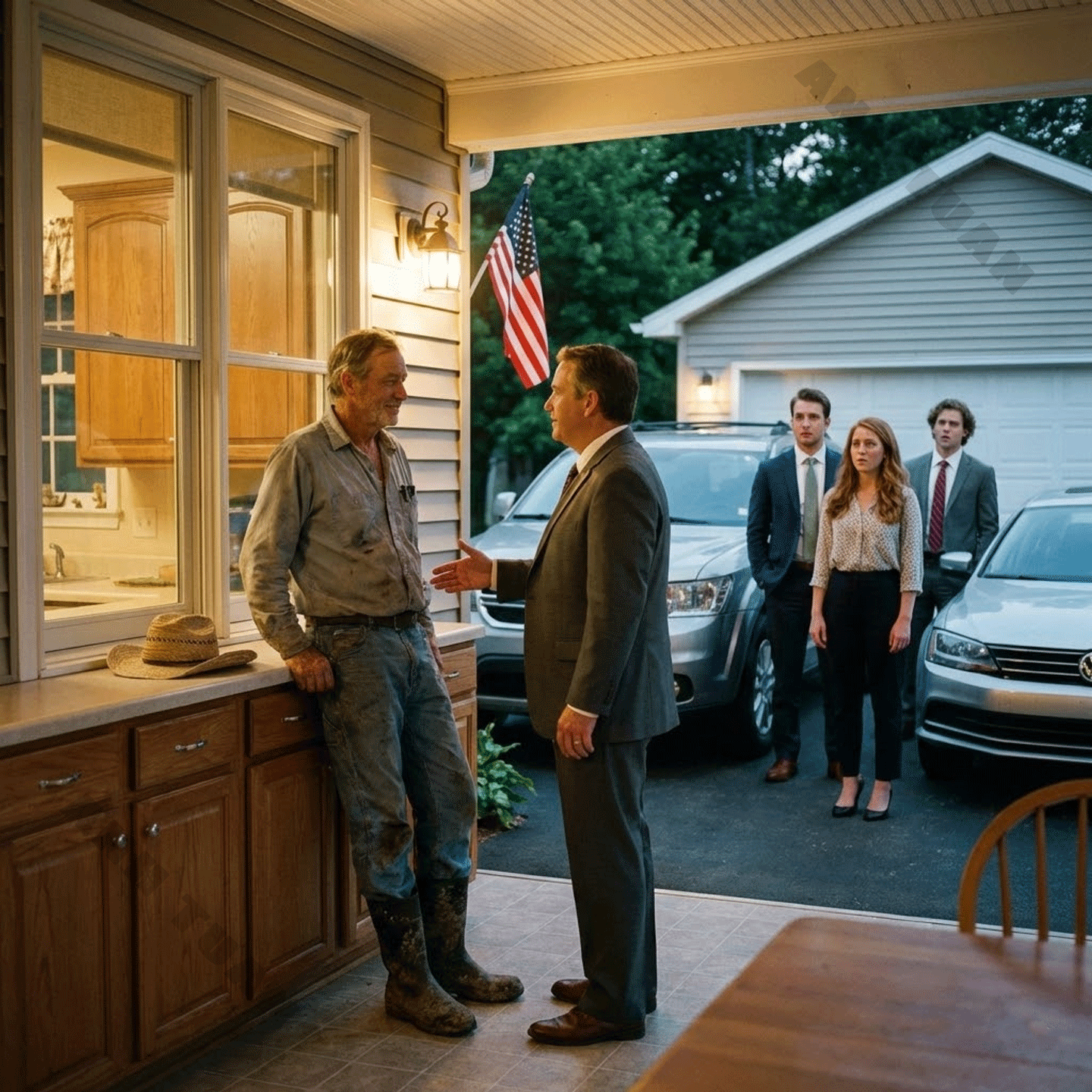

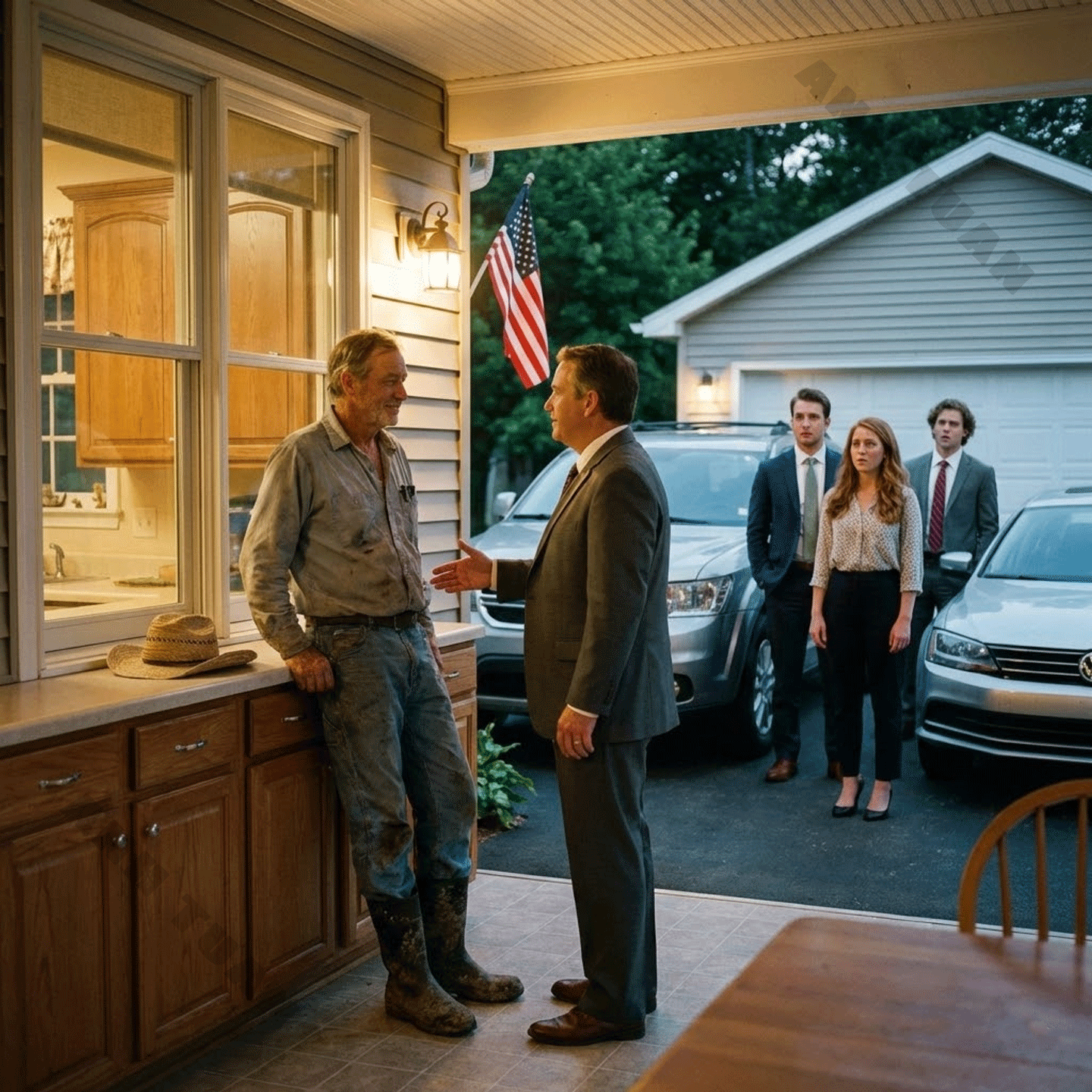

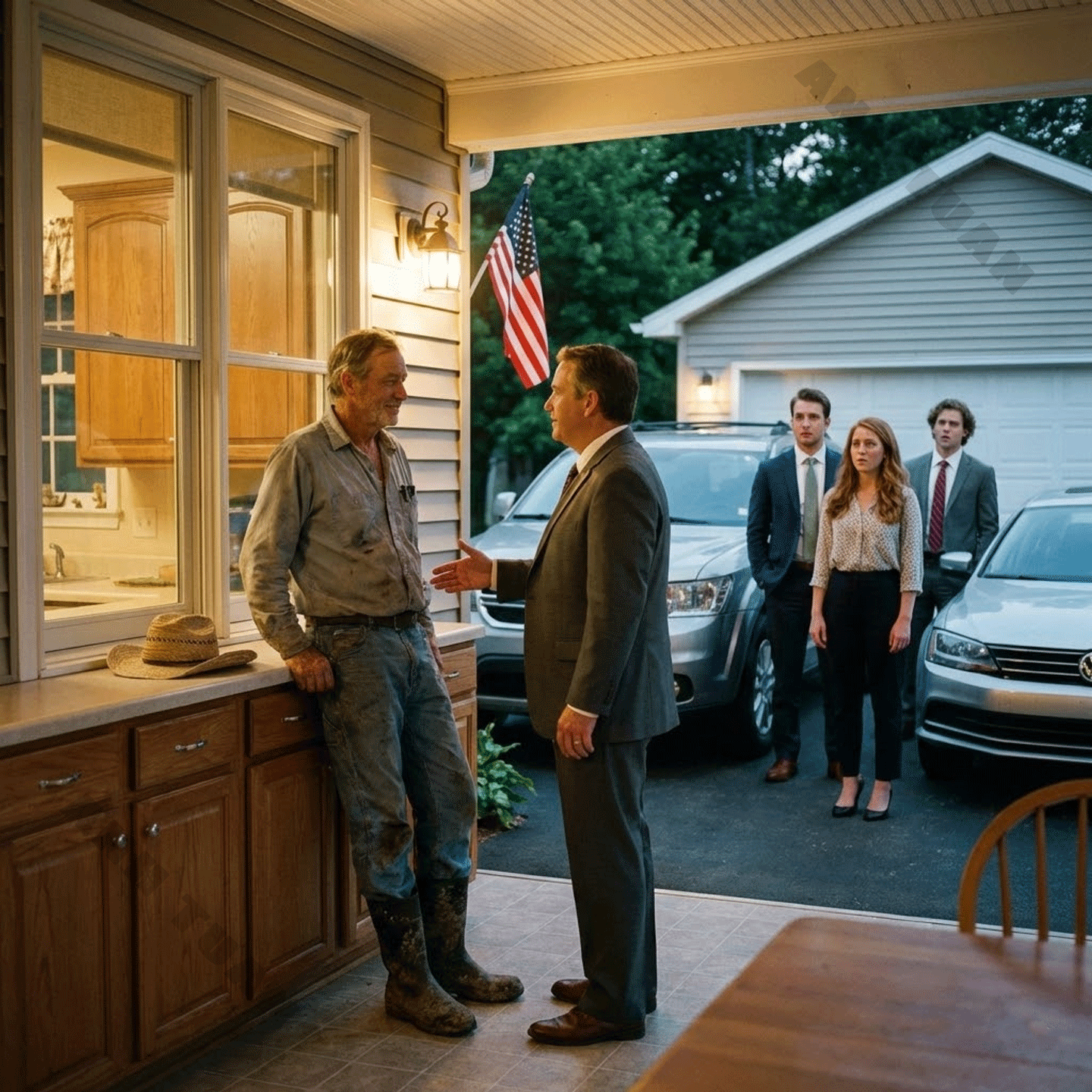

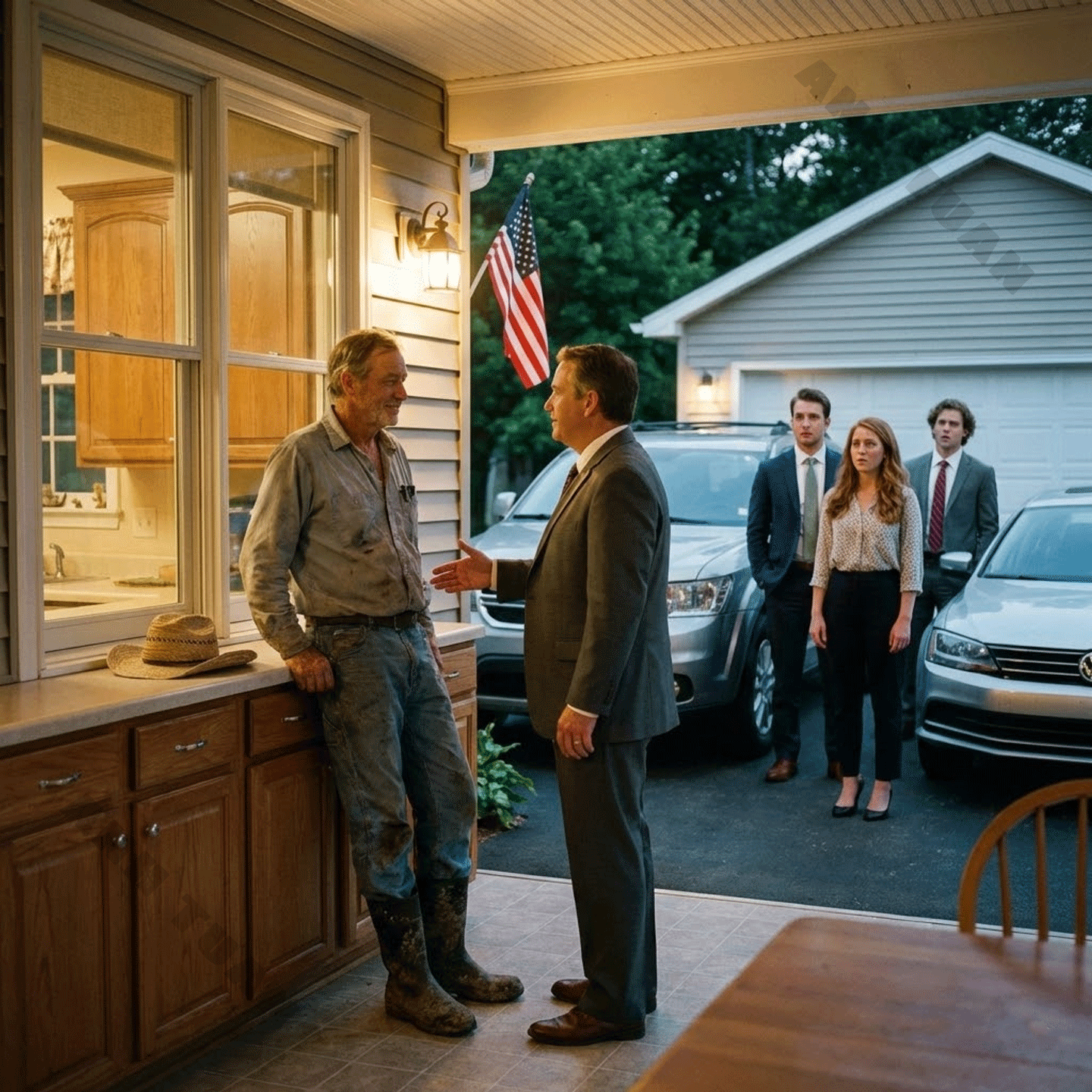

The knock wasn’t gentle, and it wasn’t rude either. It was the kind of knocking that assumed the door would open, because doors usually did when people like this arrived. Ricky moved first, eager, like he could intercept the moment and steer it toward himself, but Sheila slid in front of him with the smooth confidence of someone who had spent her adult life learning how to walk into rooms where she did not yet belong.

She opened the door with a wide smile that looked practiced, the kind you could wear without feeling it.

On the porch stood the Mayor, sunlight reflecting off his cufflinks, his suit crisp in a way that made the heat seem like it couldn’t touch him. Behind him were men who moved like shadows in sunglasses, and a couple of councilors with polite expressions, the kind of faces that knew how to look important without saying much. One of the SUVs idled at the curb, dark windows giving nothing away.

Ricky’s chest rose like he was about to deliver a pitch.

Sheila stepped forward, her voice bright.

“Good morning, Mr. Mayor. I’m Dr. Sheila Reyes,” she said, the words arranged carefully, each one meant to land. “It’s such an honor to have you here.”

The Mayor didn’t even glance at her.

He didn’t glare. He didn’t sneer. He didn’t do anything dramatic. He simply looked past her, like she was a lamp in the hallway, and walked right into the house as if he already knew where he was going.

For a second, Sheila stayed frozen with that smile still on her face, because it’s hard to recover when someone ignores you that thoroughly. Ricky’s mouth opened, then shut, and Ben, standing a step behind them, lifted his eyebrows like he couldn’t decide if he should be offended or impressed.

The Mayor didn’t stop in the living room. He didn’t pause to greet their mother. He didn’t accept the handshakes that were hovering in the air, waiting.

He went straight through the house, following the sounds of water and clinking dishes, into the kitchen.

Carding stood at the sink, sleeves rolled up, washing plates with the patient focus of someone who had washed dishes his whole life. His boots left faint smudges on the tile, but he moved carefully, respectful of the home, respectful of the space. Their mother was near the stove, drying her hands on a towel, her eyes widening when she saw who had entered her kitchen.

The Mayor stepped closer to Carding.

And then, in front of everyone, he bowed.

Not a quick nod, not a polite tilt of the head. A real bow, deliberate, unmistakable.

He reached for Carding’s hand and kissed it, like the gesture belonged to a different world, one where respect still had weight.

“Ninong Carding,” he said, his voice low and sincere. “Please forgive me for being late.”

The kitchen went silent so fast it felt like the air had been punched out of it.

The faucet kept running for half a second, then Carding turned it off. A drop of water slid down the side of the sink and fell into the drain with a soft click that suddenly sounded too loud.

Behind the Mayor, the bodyguards didn’t move, but their stillness made the moment feel even heavier, like they were guarding something invisible.

Ricky stared as if his eyes had stopped working.

Sheila’s face drained of color, her lips parting slightly, the smile gone. Ben’s hands, always composed, tightened into fists at his sides.

Their mother made a small sound, not quite a gasp, not quite a sob, and she pressed her palm to the counter as if she needed it to steady herself.

Carding didn’t pull his hand away. He didn’t flinch. He didn’t act like any of this was new. He simply gave the Mayor a quiet, respectful nod, the way one working man nods to another.

“You didn’t have to come all the way in,” Carding said calmly. “You could’ve waited in the living room.”

The Mayor shook his head, almost offended by the suggestion.

“No,” he said. “This is where you are. This is where I should be.”

Ricky found his voice, but it came out smaller than he meant it to.

“Sir,” he said, swallowing, “you know our brother?”

His gaze flicked toward Carding like he was seeing him for the first time and still couldn’t accept what he was looking at.

“The farmer?” Ricky added, and the word sounded suddenly fragile, like a label that might tear if handled roughly.

The Mayor’s expression shifted into something almost amused, but there was no mockery in it. It was the kind of smile you give when someone has made a mistake so obvious you don’t even know where to begin.

“A farmer,” the Mayor repeated softly.

He looked around the kitchen, taking in the faces, the expensive clothes, the stiff postures, the way pride had settled into this family like dust. Then his eyes returned to Carding with a kind of careful respect, as if he didn’t want to embarrass him by saying too much, but also couldn’t let the truth remain buried.

“Don Carding Reyes is the biggest landowner in the entire province,” the Mayor said, his voice clear now, carrying. “In this county and beyond. He owns the land where the mall was built. He owns the land under that subdivision you all keep talking about. He owns the acreage where the university sits.”

Ben’s mouth opened in disbelief.

Ricky blinked hard, like the words needed time to translate.

Sheila brought a hand up to her chest, not dramatic, just instinctive, like she needed to hold herself together.

The Mayor continued, not rushing.

“He’s our top taxpayer,” he said. “The person keeping half the town’s projects alive when budgets fall short.”

Silence stretched.

Outside, a car passed on the road. Somewhere down the block a dog barked again. The world kept moving, indifferent, while inside this kitchen everything had shifted.

Ricky’s voice trembled, barely controlled.

“That’s… that can’t be right,” he said. “He drives a tractor.”

Carding finally turned from the sink, drying his hands slowly with a dish towel. His face was calm, but his eyes carried something deeper, a tiredness that didn’t come from work alone.

The Mayor looked at Ricky with an expression that was almost pity.

“He drives a tractor because he chooses to,” the Mayor said. “Because he’s not trying to prove anything to anyone.”

Ben spoke next, careful and quick, as if he could still rescue his version of reality.

“But scholarships,” he said. “We studied because of scholarships. That’s what Mom told us. We were lucky.”

The Mayor’s head tilted slightly.

“And there’s more,” he said, and now his voice softened. “He funds scholarships for hundreds of students. Every year. Kids whose parents pick fruit in the heat, kids whose families can’t afford books, kids who’d never step foot on a campus without help.”

Their mother moved closer, tears bright in her eyes, her lips trembling. She had been holding this secret for so long that the truth seemed to shake her when it finally began to come out.

“Do you remember the Scholarship Foundation?” she asked, her voice breaking in the middle. “The one that helped you study, the one you always talked about like it was some miracle from the government?”

Ricky stared at her, confused, defensive.

“Yes,” he said. “That’s how we… that’s how we made it.”

Their mother nodded slowly.

“That money didn’t come from the government,” she said.

She looked at Carding, and when she spoke his name it sounded like a prayer.

“It came from your brother.”

The words fell into the room one by one, each one landing like a stone dropped into still water.

Sheila shook her head, her eyes searching Carding’s face like she expected him to deny it, to laugh, to tell them this was some kind of joke.

Carding didn’t deny it.

He just stood there, hands still damp, shirt still faded, boots still muddy, and let them hear what they needed to hear.

Their mother’s voice steadied as she went on, like the truth was giving her strength even as it hurt.

“When your father died,” she said, and her eyes flicked to the framed photo in the other room, “Carding left school. He was the first one to do it.”

Ben’s jaw tightened.

Ricky’s brow furrowed like he couldn’t understand the math.

Sheila’s lips parted, and a sound escaped her, small and broken.

“He left,” their mother repeated, slower, so there would be no misunderstanding. “He stopped going. He didn’t complain. He didn’t argue. He just did it.”

She swallowed hard.

“He worked the land,” she continued. “Every day. Dawn to dark. He learned things your father never had time to teach because your father was already exhausted. Carding learned how to negotiate leases, how to repair equipment, how to plan crops, how to deal with people who smile at you while trying to take what’s yours. He kept the farm alive.”

Her eyes filled again, and now the tears slipped down her cheeks.

“Everything he earned went to pay for your education,” she said. “Not just tuition. Books. Fees. Rent. Food. Your plane tickets when you came home for holidays. Your exam fees. The little emergencies you never told me about because you didn’t want to worry me, but somehow the money showed up anyway.”

Ricky’s throat bobbed.

Ben looked down at his hands as if he didn’t want to see them empty.

Sheila’s shoulders trembled, and for the first time since she had walked into this house, she looked less like a doctor and more like a daughter.

Their mother wiped her face with the edge of her apron, her voice soft but sharp.

“He asked me to say it was a scholarship,” she said. “So you wouldn’t feel ashamed. He didn’t want you to feel like you owed him. He didn’t want you to carry that burden while you were trying to climb.”

Ricky made a sound that might have been a laugh if it wasn’t full of pain.

“And we…” he began, then couldn’t finish.

Their mother’s gaze moved across all three of them, and there was love there, real love, but it was braided with something else now, a grief that had been simmering for years.

“Everything you’re bragging about,” she said, her voice firmer, “you owe it to the mud on his boots.”

The sentence hung in the air like a verdict.

Carding shifted slightly, as if the attention made him uncomfortable, not because he felt guilty, but because he had never done any of it for applause. His eyes went to the window for a moment, to the yard, to the fields beyond, as if his mind was checking on work that didn’t pause for family drama.

Ricky stepped forward, his hands half-raised like he wanted to touch Carding’s shoulder but didn’t know if he had the right.

“Kuya,” he said, and the word came out different now. Smaller. Realer. “Why didn’t you tell us?”

Carding exhaled slowly.

He looked at Ricky, then Sheila, then Ben.

“Because you were building your lives,” he said. “And because I knew how you looked at me.”

Sheila flinched as if struck.

Carding’s voice stayed steady, but the honesty in it cut deeper than anger would have.

“If I told you, you would’ve felt guilty,” he continued. “And guilt can turn into resentment. I didn’t want that. I wanted you to be free to become what you became.”

Ben’s eyes filled, and he blinked fast, furious at himself for it.

“But you let us treat you like that,” Ben whispered. “You let us…”

Carding’s jaw tightened slightly, the first crack in the calm.

“I didn’t let you,” he said quietly. “I endured you.”

The words were not cruel. They were simply true.

The Mayor cleared his throat, as if reminding them he was still there, that the world outside this kitchen still had schedules and responsibilities, that he had not arrived only to deliver a revelation.

He looked at Carding again, respectful.

“I’m sorry,” the Mayor said. “I didn’t know the family meeting was today, or I would’ve come earlier.”

Carding nodded, almost dismissive, like he didn’t want to make the Mayor’s presence into a bigger deal than it already was.

“It’s fine,” he said. “Thank you for coming.”

The Mayor’s eyes flicked toward the living room, toward the framed photo, toward the quiet pressure in the house.

“And the attorney,” the Mayor added. “He told me he was on the way.”

Ben looked up sharply.

“The lawyer,” Ben repeated, voice tight.

Their mother turned slightly, as if she could already hear the sound of tires on gravel.

Ricky’s stomach seemed to drop, because suddenly this wasn’t only about the past. It was about what came next, about consequences, about the kind of truth that doesn’t just break hearts but also rearranges futures.

As if on cue, headlights swept across the front windows.

A low, smooth engine sound rolled up the driveway, refined and expensive, and a white Mercedes-Benz glided to a stop like it belonged in a different world than tractors and gravel.

The car door opened.

A man stepped out in a well-fitted suit, carrying a leather folder under his arm, his hair neatly combed, his shoes too clean for this driveway.

He walked up the porch with the calm confidence of someone arriving to read words that could change everything.

Atty. Valdez stepped inside like he had done this a thousand times, like he knew exactly how a house felt when a family was holding its breath. He didn’t rush, but he didn’t linger either. He offered a nod to the Mayor first, then to their mother, then a brief glance toward the siblings lined up near the doorway with their faces still rearranging themselves around what they’d just heard.

“I made it just in time,” he said, and his voice was smooth, professional, trained to carry information without emotion.

The folder under his arm looked ordinary. That was the strange part. A thin stack of paper didn’t look like it could hold a lifetime. It didn’t look like it could crack open a family. And yet, everyone in the room understood that once it opened, nothing would go back to how it had been five minutes ago.

Their mother gestured toward the dining table, suddenly too aware of how small the kitchen felt with so many bodies and so much history inside it. The Mayor and his people stayed near the entrance, polite enough to give space, but not leaving, as if they understood that what happened here mattered beyond this home. In a town like this, names and land and generosity became part of the community’s bloodstream. Everybody depended on it, even when they didn’t know they did.

Carding wiped his hands again, slow and careful, then walked to the table without fanfare. He didn’t sit at the head. He didn’t act like a man who needed the best seat. He sat where he always sat when he came here, near his mother, close enough to notice when she needed help, close enough to reach her glass.

Ricky hovered a second before sitting, like the chair might burn him. Sheila sat with her shoulders tight and her hands folded so carefully it looked like she was trying to keep them from shaking. Ben pulled out a chair and lowered himself with the stiff caution of someone who had spent his life believing he could control outcomes if he was careful enough.

Atty. Valdez placed the leather folder on the table and opened it. The sound was small, just leather and paper, but in the silence it landed like a gavel.

“Today,” he said, “we read the special clause in Don Teodoro Reyes’s will.”

At the mention of their father’s name, their mother’s eyes went to the framed photo on the wall, as if she needed to borrow strength from it. She pressed her fingers together in her lap, knuckles pale.

Ben leaned forward.

“There’s still more?” he asked, and his voice sounded both eager and afraid, like greed and shame were wrestling inside his throat.

Atty. Valdez didn’t look at Ben when he answered. He glanced at Carding, then back down at the document, as if Carding’s presence was the real point of reference.

“Yes,” he said. “There is more.”

He took a breath, and it wasn’t a dramatic pause. It was the kind of pause a person takes when they’re about to say something that cannot be unsaid.

“For the last ten years,” the attorney continued, “Don Carding Reyes has served as trustee administrator of the estate.”

Ricky’s eyebrows lifted.

“Trustee administrator,” he repeated, like he wanted the words to mean something smaller.

Sheila’s gaze flicked to Carding, her face tight with confusion.

“You mean,” she said carefully, “Kuya didn’t inherit?”

Carding didn’t answer right away. He stared at the wood grain on the table, a pattern of lines and knots that reminded him of fields seen from above, furrows in neat rows. When he finally spoke, his voice was quiet.

“I inherited responsibility,” he said.

Atty. Valdez nodded once, as if that was the most accurate definition.

“The will,” the attorney said, “was structured to protect the estate during a ten-year period. Land, leases, taxes, development rights, and the establishment of the foundation. It required oversight.”

Ben sat back, processing. Numbers and timelines were familiar to him, and yet his face looked unsettled, like the math wasn’t adding up the way he wanted.

Ricky swallowed and tried to keep his voice steady.

“So what does that mean for us?” he asked. “Legally.”

The word “legally” was a shield. It was the closest he could get to asking, What do we get.

Atty. Valdez looked at him then, calmly, without judgment, but with a clarity that made Ricky’s stomach tighten.

“It means,” the attorney said, “that today is the day the trusteeship ends.”

The room felt like it tilted. Even the Mayor, standing a few feet away, shifted his stance slightly, attention sharpening.

Their mother closed her eyes for a moment. When she opened them, they were wet.

“And it means,” Atty. Valdez continued, “that the special clause, the test your father designed, must now be read aloud and executed.”

Ben’s voice came out thin.

“A test,” he repeated.

Sheila’s fingers tightened together.

Ricky’s gaze darted to his siblings, then to Carding, then to his mother, as if he was searching for a way to understand what kind of father designs a test that lasts ten years.

Their mother didn’t speak, but her expression did. It carried grief, love, and something like relief. As if she had been waiting for this moment, not because she wanted to punish anyone, but because she wanted the truth to finally have a home.

Atty. Valdez turned a page.

The paper made a soft whispering sound.

“Before I read it,” the attorney said, “I want to clarify something for the record. This clause is valid. It was signed, witnessed, and properly notarized. It was drafted carefully, with contingencies.”

Ben made a small, nervous laugh that didn’t sound like humor.

“Of course it was,” he muttered.

The attorney’s eyes stayed on the document.

“Don Teodoro loved all of his children,” he said, and his voice softened just enough to make the sentence feel real. “But he understood human nature. He understood what wealth can do to people. He understood what pride can do to siblings.”

Ricky’s jaw tightened as if the words were already accusing him.

Atty. Valdez lifted his gaze once more.

“This clause,” he said, “was designed to answer one question.”

He paused, then read, clear and steady, as if he were reading the weather.

“To my children,” he read, “I leave not only land and money, but a choice. The estate will remain intact, and the shares will be distributed as planned, only if my children demonstrate respect, humility, and family unity at the reading of my will.”

Sheila inhaled sharply.

Ben’s eyes narrowed.

Ricky’s hands gripped the edge of the table.

The attorney continued.

“If any of my children show arrogance, contempt, or cruelty toward the son who stayed with the land, then their shares will be automatically transferred to the Reyes Foundation for Agricultural and Educational Support.”

The words landed, and for a second nobody moved.

It wasn’t only the threat of losing money. It was the way their father had named the sin plainly. Arrogance. Contempt. Cruelty. Not misunderstanding, not accident. He had known. He had seen what could happen, maybe even in small moments, the early signs of it, and he had built a safeguard strong enough to survive his death.

Ben’s voice cracked.

“That’s… that’s insane,” he said, but it was weak, because part of him recognized it wasn’t insane. It was precise.

Ricky stared down at the table, breath shallow.

Sheila’s eyes filled, and she blinked fast, furious at herself for losing control in front of strangers, in front of the Mayor, in front of anyone.

Carding didn’t react much at all. He looked like someone who had known this page existed, even if he hadn’t held it in his hands. There was a heaviness in his shoulders that came from carrying things alone for too long.

Atty. Valdez turned another page.

“The trusteeship,” he read, “was given to my eldest son, Carding, because he has shown the character required to steward this land. He has shown the patience to hold back what he could claim. He has shown the discipline to work without applause.”

Their mother’s mouth trembled.

Ricky’s throat tightened until it felt like he was swallowing glass.

Ben’s gaze flicked to Carding’s boots, the dried mud, the cracked leather, and suddenly the boots didn’t look low-class. They looked like proof.

Atty. Valdez continued, voice steady.

“The true test,” he read, “is not who can hold wealth, but who can walk together without it. I want to know which of my children would let go of pride to stand beside their brother. I want to know who understands that dignity does not come from clothes or cars. It comes from sacrifice and love.”

There was no sermon in the tone, no dramatic flourish, but the message still cut straight through them. Because it wasn’t coming from the attorney. It was coming from the dead, from the man in the photo above the stove, from the father they had once feared and loved and then gradually replaced with their own reflections in glass office buildings.

Ben swallowed hard.

“So what now?” he asked, and it sounded like he was asking the universe.

Atty. Valdez closed the folder gently, like he was putting a child to bed.

“Now,” he said, “we determine whether the clause has been triggered.”

Ricky’s voice rose, panicked.

“But we didn’t know,” he said quickly. “We didn’t know he paid for us. We didn’t know any of this.”

Sheila nodded, desperate.

“That’s true,” she added. “We thought it was scholarships.”

Atty. Valdez looked at them with a calm that didn’t argue.

“Intent matters,” he said. “But impact matters too. And your father anticipated both. That is why the clause does not judge your past alone.”

He glanced toward Carding, then back to them.

“It judges your present,” he said. “What you do now, with the truth in front of you.”

Ben leaned forward, eyes sharp now, trying to regain footing.

“So are we disinherited?” he asked. “Is it already done?”

The attorney shook his head.

“No,” he said. “Because there is a final provision.”

He reached into the folder again and pulled out a separate document, thinner than the rest. He held it up, then placed it on the table in front of Carding.

“This,” he said, “is the decision document.”

Carding looked at it without touching it, as if paper could be heavier than land.

“What decision?” Ricky asked, voice tight.

Carding finally lifted his gaze.

His eyes moved over his siblings, and they flinched under it, not because it was cruel, but because it was honest. He looked at them like a man looking at familiar faces in a different light, trying to decide whether to keep a door open or close it forever.

Carding spoke, and his voice was steady, firm, without drama.

“You can sign this document and keep the entire fortune,” he said. “But you must leave. And you will never see us again.”

Sheila’s breath caught.

Ben’s face went pale.

Ricky’s eyes widened as if the sentence had yanked the floor out.

Carding didn’t stop. He didn’t soften it, because softening had been his habit for too long, and it had not helped them learn.

“Or,” he continued, “you can leave your cars behind, put on boots, and work with me in the fields for a month.”

Ben blinked rapidly.

“A month,” he repeated, like the time was an insult.

Carding nodded once.

“No luxuries,” he said. “No assistants. No air-conditioned offices. No titles. Just family.”

Ricky’s voice came out raw.

“You’re serious,” he said.

Carding’s jaw tightened slightly.

“I’ve never been more serious,” he replied.

Their mother covered her mouth with her hand, tears slipping free now. It wasn’t only sadness. It was the tremble of a dream she’d carried for years, the hope that her children could still come home to each other without the knives of pride.

The Mayor’s people stood very still. Nobody pulled out a phone. Nobody whispered. Even power knew when to be quiet.

Ben’s mind raced, and you could see it in the way his gaze shifted from the document to Carding to the attorney, as if he were searching for loopholes, for a way to negotiate, for a way to get the money without swallowing the humiliation.

Sheila’s eyes stayed on Carding, and there was something breaking open there. Not dignity, but the illusion of it. She thought of the hospital halls where everyone called her Doctor, thought of the way her car smelled like leather and peppermint gum, thought of the way she had rolled her eyes at her brother’s faded shirt.

She thought of her father standing at the edge of a field, hands on hips, looking out at land that didn’t care about degrees. She remembered, suddenly, a night long ago when she had come home crying from school because kids had laughed at her lunch. She remembered her father sitting with her on the porch, telling her she could become anything. She remembered Carding standing in the doorway that night, silent, watching, and she had never asked what he wanted to become.

Ricky’s hands trembled slightly as he stared at the keys in his pocket. The Ford outside suddenly felt like a costume. The title Project Manager suddenly felt like a sticker slapped on a life he didn’t fully understand. He had built bridges and systems and design plans, but he had not built anything that fed people. He had not built anything that held a family together.

Ben cleared his throat, still trying to sound in control.

“What exactly does working with you mean?” he asked. “What are you asking us to do?”

Carding leaned back slightly, exhaling as if he had expected the question.

“You’ll wake up before sunrise,” he said. “You’ll work until the sun is down. You’ll learn what it means when weather changes the plan. You’ll learn what it means when equipment breaks and you fix it because there’s nobody else. You’ll learn what it means to be tired and still show up because people depend on you.”

He looked at Ben’s hands, soft, clean.

“You’ll get blisters,” he added. “You’ll get sore. You’ll sweat. You’ll probably want to quit.”

Ben’s mouth tightened.

“And if we do it,” Ben said, “then we… we stay family?”

Carding’s gaze shifted to their mother, and something gentler moved through his expression.

“If you do it,” he said, “you’ll understand what family means without money holding it together.”

Sheila swallowed hard.

“And if we don’t?” she asked, voice small.

Carding’s eyes returned to hers.

“Then you’ll have money,” he said. “And you’ll have whatever pride you want to keep.”

Ricky’s voice cracked.

“But we were awful,” he said, and it sounded like a confession he hadn’t planned. “We were… we were cruel.”

Carding held his gaze.

“Yes,” he said simply.

The word made Ricky flinch more than any insult could have.

Atty. Valdez spoke again, calm, factual.

“The clause,” he said, “also includes a final line.”

He opened the folder, found the page, and read it.

“The heir who remained with the land may choose mercy,” he read, “if the others choose humility. But mercy is not free. It must be earned through action.”

Ben’s eyes closed for a moment. When they opened, they were wet, and that made him look furious, like he wanted to fight his own body.

Sheila wiped her cheek quickly, pretending it was nothing.

Ricky stared at Carding like he was staring at the only real thing left in the room.

Carding didn’t rush them. He didn’t push. He let the quiet stretch, because he knew something about planting. You don’t yank a seed out of the ground and demand it become a tree by tomorrow. You wait. You give it time to decide what it will be.

The house felt too small for the silence that followed.

Outside, the sun dipped lower, the light turning softer. Dust floated in the air near the porch. Somewhere beyond the yard, fields waited, steady, indifferent, ready to ask the same question they always asked.

Who are you when the work begins.

Ricky’s fingers slid into his pocket and wrapped around his keys. He pulled them out slowly, the metal glinting in the light, and for a second he hesitated, as if he could still choose to pretend.

Then he set them on the table.

The sound was small, a soft clink, but it echoed like thunder in Ricky’s chest.

His face crumpled, and the tears that came next weren’t pretty. They weren’t theatrical. They were the ugly kind that happen when a man realizes he has been wrong for a long time and doesn’t know how to live with it.

“I don’t want millions,” Ricky said, voice breaking. “I want my brother.”

Sheila inhaled sharply, like the words had cracked something inside her too. She reached into her purse, pulled out her keys, and placed them beside Ricky’s.

Her voice trembled.

“Teach me how to plant,” she said, and it was the first time she had spoken to Carding as if he had something she needed.

Ben stared at his hands for a long moment. His keys sat in his pocket like a weight. His car outside represented comfort, control, distance from mud.

He looked at Carding, and then he looked at their mother, and something in his expression softened, as if he was finally seeing the years she had carried.

He pulled out his keys and set them down with care, like an offering.

“Family is worth more than money,” Ben said, and he sounded like he was trying to convince himself as much as anyone else.

Their mother’s shoulders shook, and she covered her mouth again, tears spilling, but this time there was relief in them, a kind of healing she had not dared hope for.

Carding stared at the three sets of keys on the table. For a long moment he didn’t move. His jaw worked slightly, like he was chewing on a thought too heavy to swallow. Then he reached out and placed his palm flat on the table near the keys, not touching them, just near them.

“You don’t have to do this for me,” he said quietly.

Ricky shook his head, wiping his face with his sleeve, not caring who saw.

“We have to do it because of you,” he replied. “Because you carried us.”

Sheila nodded, tears slipping again.

“And because we don’t want to be the kind of people we were,” she whispered.

Ben’s voice was steady but low.

“I don’t want to win if winning means losing my family,” he said.

Carding’s eyes closed briefly, like he was bracing himself against something. When he opened them again, they were wet, and the sight of that, the farmer brother with tears he didn’t show often, hit the siblings harder than any legal clause ever could.

Carding stood.

“All right,” he said.

The word was simple, but it held a lifetime.

He looked at the attorney.

“They choose humility,” Carding said. “So I choose mercy.”

Atty. Valdez nodded, then wrote something quickly, the pen scratching paper like the sound of a new path being drawn.

The Mayor exhaled, a subtle release, and for the first time since he arrived, his expression looked warm.

Their mother pressed her hands together and whispered something that sounded like thanks, but it wasn’t directed at anyone in the room alone. It was directed upward, outward, into the space where grief and faith and love meet.

Carding looked at his siblings again, and his voice turned practical, grounded.

“We start tomorrow,” he said. “Before sunrise.”

Ricky sniffed and nodded.

Sheila swallowed hard and nodded.

Ben nodded once, like he was signing a contract with his spine.

Outside, the late-day heat still sat on the land, but the light was changing. The house still held all the old memories. The driveway still held the expensive cars. The tractor still sat there with dried mud on its tires.

But something had shifted.

Not in paperwork alone.

In the heart of the family.

Morning came the way it always came in farm country, not gentle and poetic but firm and immediate. The sky was still dark when Carding knocked on the guest room doors, his knuckles steady, his voice low but unquestionable. There was no snooze button on this life. There was no calendar invite. The day didn’t care what you did for a living yesterday.

Ricky sat up first, disoriented, reaching instinctively for a phone that wasn’t there. For a moment, his mind tried to pull him back toward the familiar rhythm of emails and meetings. Then he remembered the keys on the table, remembered the way his father’s words had cut through the room, remembered the feel of shame and love tangled together in his chest.

Sheila was already awake, staring at the ceiling, her hair loose for the first time in years without looking carefully arranged. She had slept lightly, waking every hour, as if her body couldn’t decide if this was punishment or salvation.

Ben got up last, moving slower than the others, like his body already wanted to argue, but his face looked set. He had spent his whole life believing discipline was something you applied to numbers and budgets and schedules. He was about to learn what discipline looked like when it was measured in blisters.

In the kitchen, their mother had coffee brewing. The smell of it filled the house, rich and bitter, a lifeline. She didn’t talk much. She watched them with eyes that had seen them as babies, teenagers, adults, and now as something else, something raw and uncertain. When she handed them mugs, her hands shook slightly, and she pretended not to notice.

Outside, the air was cooler, damp with the last of night, but the promise of heat was already there, waiting.

Carding stood near the porch with three pairs of boots lined up like a quiet challenge. They weren’t new. They were work boots, broken in but sturdy, leather worn soft in places, hard in others. He didn’t smile when he handed them over. He didn’t tease. He treated the moment like a rite, something too serious for jokes.

“Put these on,” he said.

Ricky stared at the boots like they were an insult, then like they were a gift, then finally like they were what they were: the doorway to a life he had never respected because he had never understood it.

Sheila bent and slid her feet in carefully, as if she were stepping into someone else’s skin. The boots were heavy, and they made her feel strange, grounded in a way her heels never had.

Ben hesitated, then pulled his on and tightened the laces, jaw clenched.

Carding gestured toward the tractor and the pickup parked beside it, an old American work truck that had seen more seasons than any of their cars ever would.

“We’re not starting with the easy jobs,” he said. “You learn from the ground up.”

The fields behind the house stretched out in rows, dark soil divided into lines like the land was showing its spine. In the distance, you could hear irrigation systems hissing, the faint mechanical whir of something turning, the far-off call of a bird already awake and hungry.

Ricky swallowed.

“What exactly are we doing?” he asked, and he tried to sound steady, but his voice betrayed him.

Carding looked at him, expression unreadable.

“First,” he said, “you’re going to understand what you’ve been standing on your whole life.”

He handed Ricky a pair of gloves and pointed him toward a section where crates were stacked, waiting. He told Sheila to follow him to the shed where tools were kept. He sent Ben to help lift and carry, because Ben’s body looked strongest, even if his hands were soft.

The first hour was almost quiet.

Not because it was easy, but because the work demanded attention. Ricky learned quickly that lifting the wrong way made your back protest. Sheila learned that gloves didn’t stop your palms from sweating. Ben learned that even simple tasks became exhausting when they didn’t end after a spreadsheet.

Carding didn’t hover. He didn’t bark orders like a tyrant. He moved with a calm efficiency that made him look like he belonged to the land the way some people belong to a city. He showed them how to hold tools, how to carry loads, how to pace themselves.

“Don’t rush,” he told Ricky when Ricky tried to power through like the work was a competition. “This isn’t about showing off.”

Ricky nodded, breath already heavier.

By midmorning, the sun was high, heat pressing down hard. Sweat ran down Ricky’s neck into his shirt. Sheila’s hair stuck to her temples. Ben’s arms shook slightly when he lifted crates, not from weakness, but from unfamiliar strain.

They stopped for water under the shade of a tree. Carding drank slowly, eyes scanning the field like he was reading it.

Sheila wiped her face with a sleeve and looked at him, voice hoarse.

“How do you do this every day?” she asked.

Carding shrugged.

“You do what you have to do,” he said. “The land doesn’t care how you feel.”

Ben stared at his hands. A blister had already formed at the base of his thumb, angry and swelling.

“This is insane,” he muttered before he could stop himself.

Carding looked at him calmly.

“So is raising three kids through college on land that people wanted to steal,” he said. “So is keeping a family together when pride is trying to rip it apart.”

Ben swallowed. The words sank into him like salt.

They worked again.

By afternoon, the initial shock had turned into something else. Not comfort, but rhythm. Ricky began to move differently, less frantic, more aware. Sheila started listening more closely, watching Carding’s hands, copying his movements. Ben, despite his complaints, was stubborn. Once he started something, he hated quitting, and that stubbornness became his lifeline.

At dinner that night, their bodies ached in ways their minds hadn’t expected. Ricky’s shoulders felt like stones. Sheila’s legs trembled when she sat. Ben’s hands were raw, the skin tender where blisters threatened to break.

Their mother served food quietly, eyes soft, and for the first time in years, the table didn’t feel like a stage. It felt like a family.

Ricky ate without talking much. When he did speak, his voice was lower, less polished.

“Kuya,” he said finally, looking at Carding, “when did you start… becoming… this?”

He couldn’t find the right word. Powerful? Wealthy? Important? None of them fit.

Carding chewed slowly, swallowed, and then said the simplest thing.

“I never became anything,” he replied. “I just stayed.”

The sentence hit Ricky like a slap because it was so plain. Ricky had spent his whole life chasing becoming. Carding had built everything by refusing to leave.

Sheila stared down at her plate, then spoke softly.

“I used to think staying meant you failed,” she admitted.

Carding’s gaze didn’t sharpen. He didn’t punish her for the confession. He simply nodded as if he’d expected it.

“Sometimes staying is the hardest thing,” he said.

Ben set his fork down.

“And you never wanted to leave?” he asked.

Carding looked toward the window where darkness pressed against the glass, fields invisible but present.

“Of course I wanted to leave,” he said quietly. “I wanted to be a lot of things. But I wanted you three to have choices more.”

Their mother’s eyes filled again, but she didn’t cry this time. She looked proud and broken and grateful all at once.

The days blurred into each other after that.

The work was relentless. Early mornings, long hours, sunburns, sore muscles, hands that grew tougher whether they wanted to or not. Ricky learned to keep his mouth shut when he didn’t know something, which was more often than he liked. Sheila learned patience, the kind you can’t fake. Ben learned humility, the kind that feels like swallowing rocks at first and then slowly, strangely, starts to taste like peace.

There were moments of breaking.

Ricky got frustrated one afternoon when equipment jammed and his instincts screamed to force it. He cursed under his breath and slammed a fist against metal, then immediately regretted it when pain shot up his arm. Carding didn’t scold him. He simply stepped in, showed him how to loosen the tension, how to listen to the machine, how to respect it.

“Your world is about control,” Carding said quietly. “This world is about cooperation.”

Sheila cried one evening in the bathroom, sitting on the edge of the tub with her hands shaking, not because the work was only hard, but because she felt the weight of years pressing on her chest. She had been praised her whole life for being strong. This strength was different. This strength didn’t come with applause. It came with silence.

Ben nearly quit on day ten.

It was a brutal day, heat over a hundred, the kind of heat that makes the air shimmer and your thoughts slow. They were moving irrigation lines, heavy and awkward. Ben’s hands were already raw, and when he lifted one wrong, pain tore through his back like a hot wire.

He dropped it and staggered, breath tight.

“I can’t,” he said, voice ragged, and the words sounded like surrender.

Carding walked over slowly, not rushed, not alarmed. He stood beside Ben, looking out over the fields.

“You can,” he said.

Ben shook his head, sweat running down his face, eyes wild.

“No, I can’t,” he insisted. “I’m not built for this.”

Carding turned to him, and his voice softened, but the firmness remained.

“You think I was built for it?” he asked. “You think I woke up one day and wanted to be responsible for everything? You think I wanted to watch Dad die and then figure out how to keep the land from being taken? You think I wanted to spend nights worrying about taxes and leases while you three were safe in dorm rooms?”

Ben’s face crumpled. The pain in his back suddenly felt like nothing compared to the pain in his chest.

Carding looked at him steadily.

“You’re not here because you’re built for it,” he said. “You’re here because you chose your brother.”

Ben’s eyes filled. He bent forward, hands on knees, breathing hard, and then, slowly, he nodded.

He picked up the irrigation line again.

They kept going.

By the third week, something subtle changed.

Ricky’s laugh sounded different. It wasn’t the sharp, bragging laugh from the garage. It was quieter, more real. Sheila’s eyes were softer, and she stopped flinching at dirt. Ben began to speak less about money and more about people, about the workers’ families, about the kids who ran through the fields after school, about the way everyone depended on harvest season like it was a heartbeat.

Their mother watched it all with a quiet amazement, like she was witnessing a miracle she didn’t want to name out loud in case it disappeared.

One afternoon, Carding took them to the edge of the property where the town’s new development pressed against old land. You could see the mall in the distance, its sign bright even in daylight. You could see the university buildings beyond it, modern and clean.

Ricky stared at it, remembering what the Mayor had said.

“This is all…” he began.

Carding nodded.

“Parts of it,” he said. “Leased. Some sold. Carefully.”

Sheila looked at him, voice small.

“Why didn’t you just… live like a rich man?” she asked.

Carding’s gaze moved over the land, the fields stretching out like an answer.

“Because the land doesn’t stay rich if you treat it like a trophy,” he said. “And because I didn’t want you to think money was the point.”

Ben let out a slow breath.

“And the scholarship foundation,” Ben said. “You really… you really paid for all of that.”

Carding nodded once.

“I did,” he said.

Ricky swallowed hard.

“And you watched us brag,” Ricky whispered. “You watched us talk like we were self-made.”

Carding looked at him, and there was no cruelty in his eyes, just the steady truth.

“I watched,” he said. “And I waited.”

Ricky’s face twisted, shame rising again, but something else rose too, something like gratitude and awe.

“What kept you from hating us?” Sheila asked, and her voice shook.

Carding was quiet for a moment, as if he was choosing words carefully, the way you choose seeds.

Then he said, “Mom.”

He looked back toward the house, toward their mother, toward the porch where the faded flag hung and moved in the breeze.

“She never stopped hoping you’d come back,” he said. “Not to the house. To us.”

The month moved toward its end, and by the time the final day arrived, their hands were callused, their skin sun-browned, their eyes changed. They weren’t farmers, not yet, maybe never fully, but they were no longer strangers to the world that had carried them.

That morning, Carding woke them up as usual, but instead of sending them to the fields, he told them to wash up, put on clean clothes, and get in the old truck.

Ricky’s heart tightened.

“Where are we going?” he asked.

Carding’s mouth curved slightly, not quite a smile, more like a quiet promise.

“You’ll see,” he said.

They drove through the property, then onto a paved road, heading toward town. The landscape shifted from fields to storefronts, from tractors to traffic lights. Ricky watched familiar buildings pass and felt strange, like he was seeing everything with new eyes.

They turned down a road lined with construction equipment.

Cranes rose against the sky.

Dump trucks idled.

A chain-link fence surrounded a wide open site where concrete was being poured and workers moved like ants across a growing foundation.

Ben leaned forward, squinting.

“Another mall?” he asked, and the old Ben’s cynicism slipped through automatically, because malls were what men with land built when they wanted more money.

Carding stopped the truck and killed the engine.

He looked at them, face calm.

“No,” he said.

He stepped out and gestured toward the site. A large sign stood near the fence, covered with a tarp.

Carding walked over, grabbed the edge of the tarp, and pulled.

The sign underneath was clean and bold.

Reyes Agricultural and Medical Center.

Ricky’s breath caught.

Sheila stared, mouth open, hand flying to her chest.

Ben’s eyes widened, and for once he forgot to calculate.

Carding looked at them, and his voice was steady, grounded, almost gentle.

“You will run it,” he said.

Sheila’s voice cracked.

“What?” she whispered.

Carding nodded.

“For the people,” he said. “For the farmers.”

Ricky stepped closer to the fence, staring at the foundation, at the workers, at the scale of it. He felt something tighten in his throat.

“This is…” he began.

Carding cut in softly.

“This is what Dad wanted,” he said. “This is why the foundation exists. This is why the land matters.”

He looked at Sheila.

“You know medicine,” he said. “But now you know the people who need it, and you know why they don’t always get it.”

He looked at Ben.

“You know numbers,” he said. “Now you know the cost of ignoring the hands that feed the town.”

He looked at Ricky.

“You know systems,” he said. “Now you know what happens when a system forgets the workers at the bottom.”

Ricky’s eyes burned. He nodded, unable to speak.

Sheila wiped her cheek quickly, embarrassed by the tears, but she didn’t hide them like before.

Ben swallowed hard.

“And you?” Ben asked. “What will you do?”

Carding looked back toward the fields visible in the distance, the green lines and brown earth.

“I’ll stay,” he said simply.

The same answer as before.

But now it sounded like something holy.

That night the whole town celebrated the harvest, the way small American towns still sometimes do when they remember they’re made of people, not just projects and property lines. Strings of lights were hung across the community lot near the fairgrounds, and the air smelled like grilled corn, smoked brisket, and sweet funnel cake. Someone set up a small stage with speakers that crackled a little when the microphone was tested. Country music drifted out in lazy waves, and in between songs you could hear laughter, the clink of plastic cups, the thud of boots on packed dirt.

There were pickup trucks everywhere, dusty and proud, tailgates down, kids running barefoot in the grass, teenagers leaning against fences pretending they weren’t watching each other. Old men in caps sat on folding chairs and talked about rain like it was politics. Women carried casseroles and paper plates like they were offering peace. The town’s American flag, bigger than the one on the Reyes porch, hung high over the lot and moved slowly in the warm evening breeze.

The Mayor showed up again, less formal this time, jacket off, sleeves rolled, trying to look like a man who belonged to the people he served. Councilors came too, and a few business owners who had once pretended they didn’t see Carding when he walked into meetings. Tonight, they saw him. Tonight, everyone saw him.

And for the first time in a long time, the three professionals didn’t stand apart like they were visitors.

Ricky wore a plain shirt, not pressed perfectly, and his hands, once clean and careful, were rough now. When he laughed, it wasn’t that sharp garage laugh meant to show off. It was the kind of laugh that came from being tired and alive and surprised by your own humility.

Sheila wore jeans and boots that still looked a little strange on her, but she didn’t look like she wanted to slip out of them. She moved among the tables, talking to older women and younger mothers, listening more than she spoke. When someone mentioned a sick child, she didn’t jump into doctor mode like she was performing. She asked questions gently, with a new kind of patience, the kind that comes from having felt the sun on your own back.

Ben stood near a cooler, handing out drinks, arguing with an older farmer about whether next season would be dry. His hands looked like hands now, not just tools for holding pens. He caught himself doing mental math out of habit and then shook his head, smiling faintly, like he was learning to live in the moment without tallying it.

People noticed.

They noticed the calluses. They noticed the way the three siblings didn’t flinch at dirt or sweat. They noticed the way they looked at Carding, not with embarrassment, not with disgust, but with something like respect and tenderness. A few of the older folks exchanged glances, the kind that says, So that’s what happened.

Carding moved through the celebration quietly, greeting people, shaking hands, nodding. He didn’t soak in attention. He didn’t pretend to be a hero. He looked like he always looked, grounded, steady, but there was a softness around his eyes now, a lightness that hadn’t been there before.

Their mother sat at a table near the edge of the lights, watching everything as if she couldn’t quite believe it was real. The glow from the bulbs made her look younger, not because time had reversed, but because the tension in her face had eased. For years she had carried a secret like a stone in her chest. Now, the stone was still there, but it felt shared, understood.

When Ricky walked over and sat beside her, she reached out and touched his forearm, fingertips resting on the rough skin as if she needed proof.

“You’re hurt,” she murmured.

Ricky shook his head quickly.

“It’s fine,” he said, and he meant it. “It’s… I don’t know, Mom. It’s different.”

She looked up at him, eyes shining.

“It’s real,” she said softly.

Sheila came to the table next, holding a paper plate of food, and she hesitated before sitting, like she still didn’t trust herself to take up space without earning it. Then she sat, close to her mother, close to Ricky, and for a moment she just watched the crowd, her face open.

Ben joined them, lowering himself carefully like his back still remembered pain.

Across the lot, Carding stood talking with a group of farmers, laughing quietly at something someone said. The Mayor walked by and nodded at him with visible respect, not the kind that demanded anything back, but the kind that said, I know what you’ve done.

Ricky watched Carding for a long moment, his throat tightening.

“I didn’t know,” he whispered, like the sentence still needed to be said. “I really didn’t know.”

Their mother placed her hand over his.

“I know,” she said. “But you knew enough to choose him when it mattered.”

Ricky’s eyes burned. He blinked hard.

“Why didn’t you ever tell us?” Sheila asked, and her voice was careful, not accusing, just aching.

Their mother looked out at the lights, at the people, at the land beyond the fairgrounds that still breathed and waited.

“Because I didn’t want you to feel trapped by gratitude,” she said. “And because Carding asked me not to. He thought it would make you resent him.”

Ben’s mouth tightened.

“And you believed him,” Ben said, and it wasn’t a question.

Their mother nodded slowly.

“I’ve lived long enough to know how pride works,” she said. “Sometimes it protects you. Sometimes it poisons you. He was trying to protect you.”

Sheila stared down at her hands.

“And we poisoned him anyway,” she whispered.

Ricky shook his head.

“We tried,” he corrected, voice cracking. “But he didn’t… he didn’t become bitter. He stayed… good.”

Ben’s eyes followed Carding too, his expression tight with remorse.

“I don’t know how to make up for ten years,” Ben said quietly.

Their mother’s gaze stayed soft.

“You don’t make up for it by saying sorry,” she said. “You make up for it by living differently.”

The music shifted. Someone on stage started playing a slower song, a familiar country ballad that people hummed along to without thinking. Couples swayed. Kids ran in circles until they collapsed laughing. The night smelled like food and dust and warm grass.

Carding finally walked over to their table. He didn’t announce himself. He just arrived, like he always did, and stood behind their mother for a moment, resting a hand on her shoulder. The gesture was simple, but it carried everything.

Their mother looked up at him, eyes full.

“Mission accomplished,” Carding said quietly.

It was the first time he sounded like he was allowing himself pride, but it wasn’t pride in wealth. It was pride in something far rarer: healing.

Their mother smiled and tilted her face up toward the sky, where stars were beginning to show above the glow of town lights. For a second, her expression looked like relief, like gratitude, like she was talking to someone who wasn’t here anymore.

Then she looked back at her children, all of them, and the smile stayed.

Ricky’s voice trembled.

“Kuya,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

Carding didn’t answer with words right away. He pulled out a chair and sat beside them, elbows resting on his knees, hands clasped loosely. His gaze moved across their faces, and it was strange how familiar they suddenly looked, not like competitors or strangers, but like kids from the same house, the same table, the same father.

“I know,” he said finally, and his voice was quiet. “But don’t say it like you’re trying to erase it. You can’t erase it.”

Ricky flinched.

Carding held up a hand gently, not to stop him, but to steady him.

“You can change what comes next,” Carding continued. “That’s all any of us can do.”

Sheila swallowed hard.

“I felt stupid out there,” she admitted, nodding toward the fields in the distance. “The first week, I felt… useless.”

Carding nodded.

“You weren’t useless,” he said. “You were learning humility. That’s not useless. That’s rare.”

Ben cleared his throat, eyes shiny.

“I kept thinking about Dad,” he said. “How he… how he planned all this.”

Carding’s gaze lifted toward the night.

“He loved you,” he said simply. “He just didn’t want money to turn you into people you wouldn’t recognize.”

Ricky swallowed.

“And you,” Ricky said. “You didn’t want money to turn you into someone bitter either.”

Carding’s mouth curved slightly.

“I had the land,” he said. “The land keeps you honest. You can’t lie to soil.”

Their mother laughed softly through tears.

“That’s true,” she murmured.

Carding leaned back slightly, looking out at the celebration, and for a moment he was quiet. The lights reflected in his eyes. The music drifted. Somewhere nearby, a little kid squealed with laughter. It was all ordinary and sacred at once.

Ricky stared at his hands, callused and scratched, and he felt something shift again. For years, he had thought mud was something you avoided, something that lowered you, something that made you less.

Now he understood what his mother had meant.

Mud on your boots didn’t reduce a person’s worth.

It revealed who was truly holding the world up.

A farmer didn’t have to beg for respect. A farmer fed the respect of others without being thanked. A farmer stood under the sun and made sure other people could sit in air conditioning and argue about progress.

Sheila looked around at the people eating and laughing, at the workers whose bodies carried the town, and her throat tightened.

“I’m going to do it,” she said suddenly, voice firm. “The medical center. I’m going to run it right.”

Carding turned to her, expression calm.

“I know,” he said.

Ben nodded too.

“And I’ll make sure it doesn’t become another place that takes from them,” Ben added, voice steady. “No hidden fees. No tricks. No pretending.”

Ricky’s jaw tightened.

“And I’ll build systems that actually serve people,” he said. “Not just investors. Not just the ones who already have everything.”

Carding listened, and he didn’t praise them like a boss handing out gold stars. He simply nodded, as if this was what he had been waiting for all along.

Their mother reached across the table and took all three of their hands, her fingers warm against rough skin. She squeezed, and it was like she was sealing something, not with paperwork, but with touch.

The celebration rolled on.

People came over to say hello, to shake hands, to thank Carding quietly. Some looked at the siblings with cautious curiosity, like they were waiting to see if this change would last past the spotlight of a public night. The siblings didn’t perform. They didn’t overcompensate. They just stayed, listening, laughing, eating, learning how to belong.

Late in the evening, when the music softened and the crowd thinned, the Reyes family walked back toward the truck together. The air had cooled. The stars were sharper. The fields beyond town were quiet but alive, waiting for dawn, waiting for work.

Ricky glanced toward the parking lot where his Ford sat untouched at home, keys still on the table. He felt a strange relief thinking about leaving it behind again tomorrow. The car had once been a symbol. Now it was just a car.

Sheila adjusted her boots, the leather creaking. She thought of hospital corridors and clean white walls, and she didn’t hate them. She just saw them differently now. She saw what those walls often hid.

Ben rubbed his thumb over a callus and felt, for the first time in years, something like peace in not needing to win.

Carding walked beside their mother, steady as ever.

As they reached the edge of the lights, their mother paused and looked back once at the celebration, then at her children, then at the sky.

For years she had been afraid the family would break into separate worlds.

Tonight, the worlds had finally touched.

And the strange part was, it hadn’t happened because of money.

It had happened because a man in muddy boots refused to let love become bitterness, and because three proud siblings finally chose to step into the mud instead of standing above it.

Before they climbed into the truck, Carding turned slightly, eyes moving over the land beyond town, over the place that had demanded everything from him and had also given him everything.

Then he looked at his siblings, and his voice was quiet, almost intimate.

“You thought wealth was what you could show,” he said. “Cars. Titles. Degrees.”

Ricky swallowed.

Sheila’s eyes filled again.

Ben’s jaw tightened.

Carding nodded toward the dark fields.

“But real wealth,” he continued, “is what you can carry without anyone applauding. What you can give without being seen. Who you are when nobody’s impressed.”

They stood there in the cool night, breathing the same air, listening to the faint hum of town lights behind them, and Ricky felt the weight of the question that would follow them long after tonight’s celebration faded.

Because the lawyer’s clause had tested them once, in one dramatic day, but life would keep testing them in quieter ways.

Carding opened the truck door for their mother, the way he always did. She climbed in slowly, and before she closed the door, she looked at the three younger ones.

Her voice was soft, but it carried.

“You’ve learned what your father wanted you to learn,” she said. “Don’t forget it when the world tries to make you proud again.”

They nodded, all three, and they meant it, but meaning it was only the beginning.

As the truck rolled away from the lights, leaving the celebration behind, the road stretched ahead in the dark, and the land beside it waited like a steady heart.

And if you’re honest, you know the question isn’t really about Carding, or the will, or the keys on the table.

It’s about you.