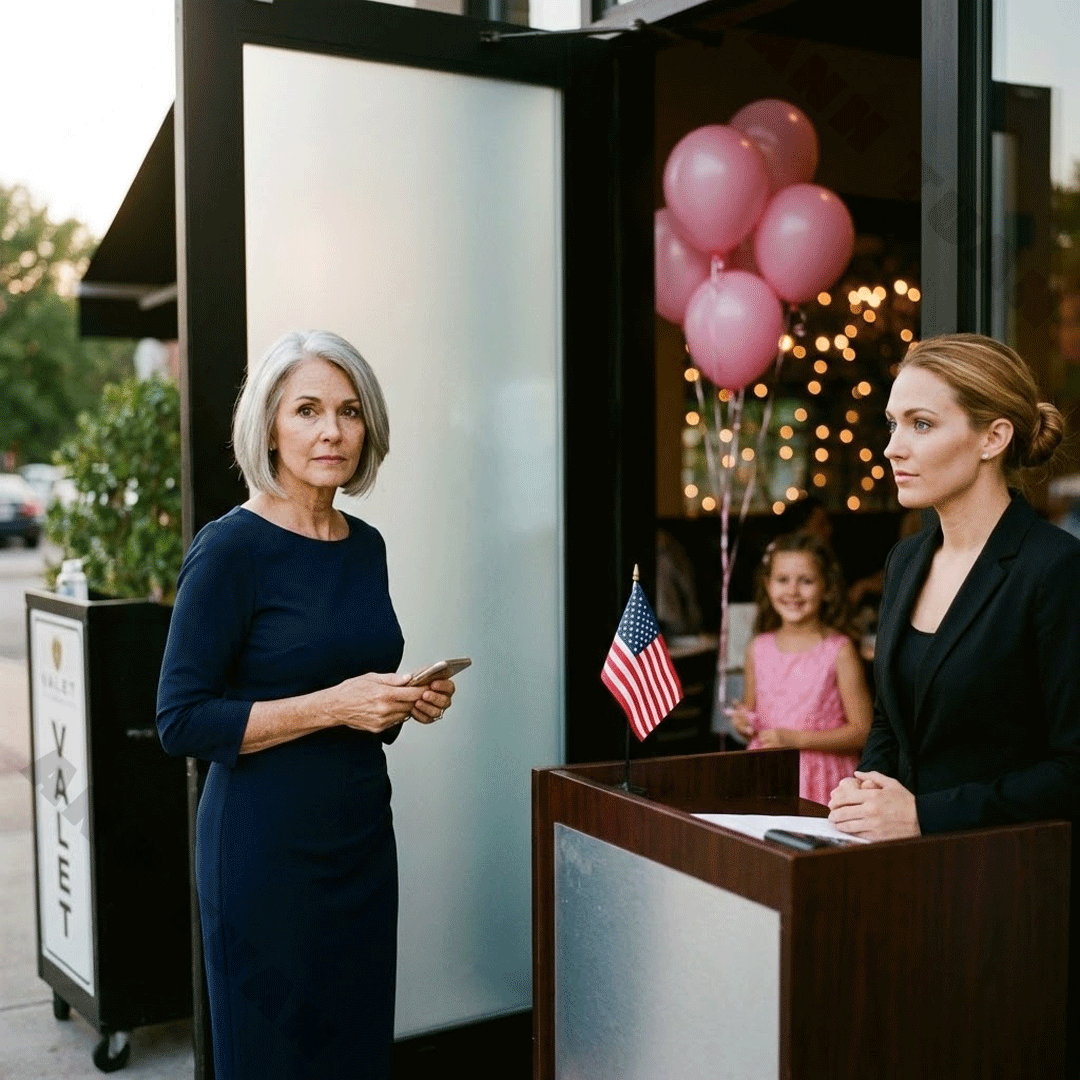

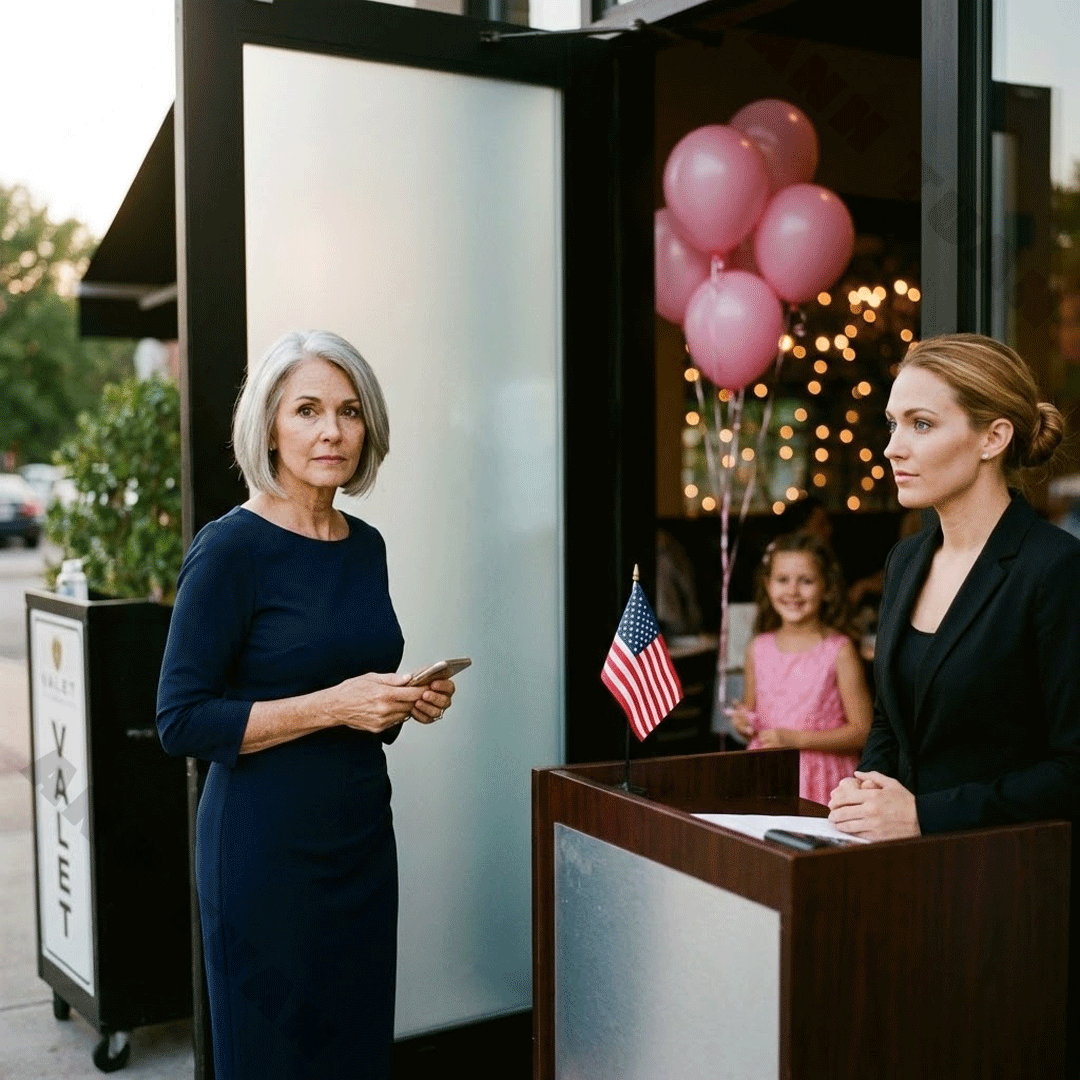

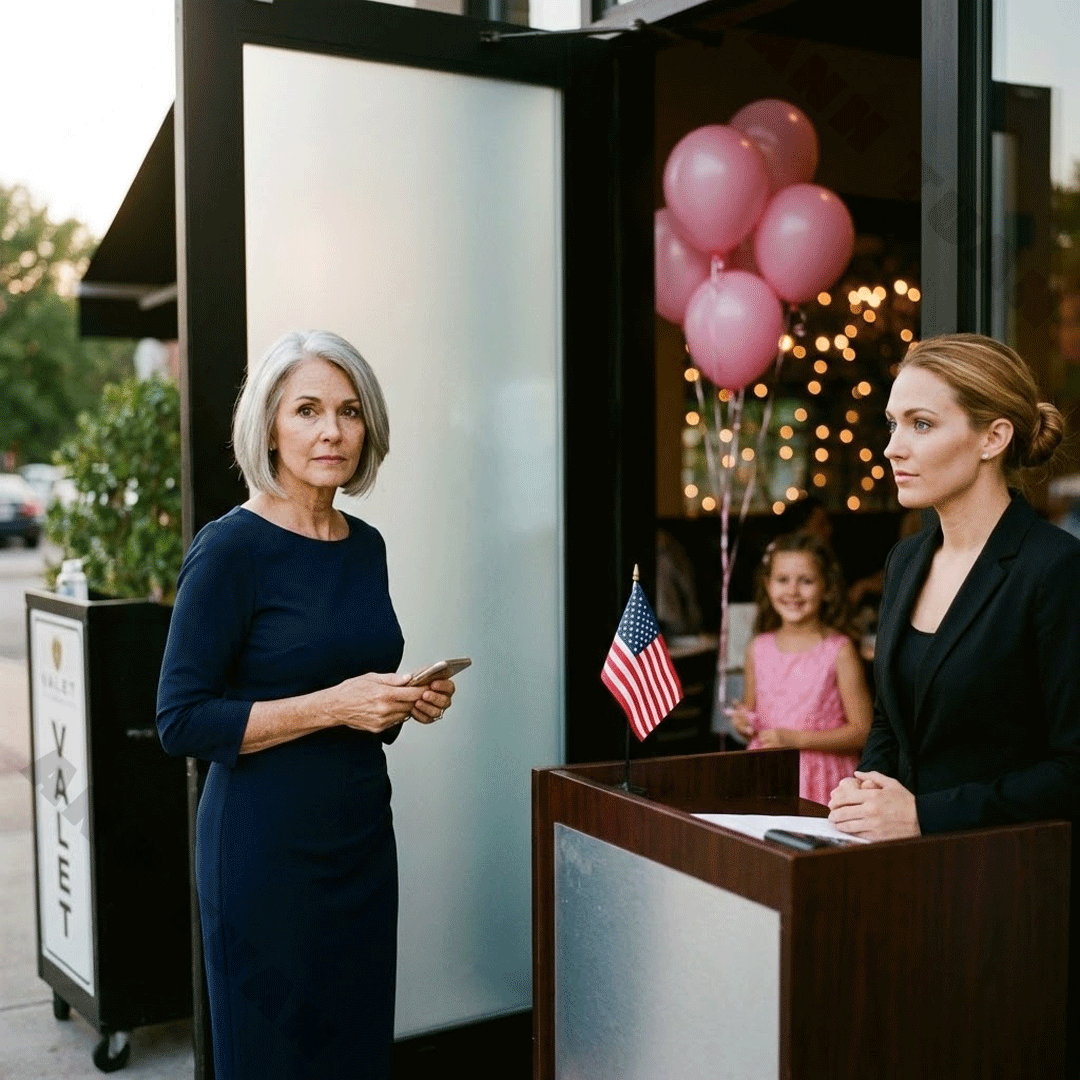

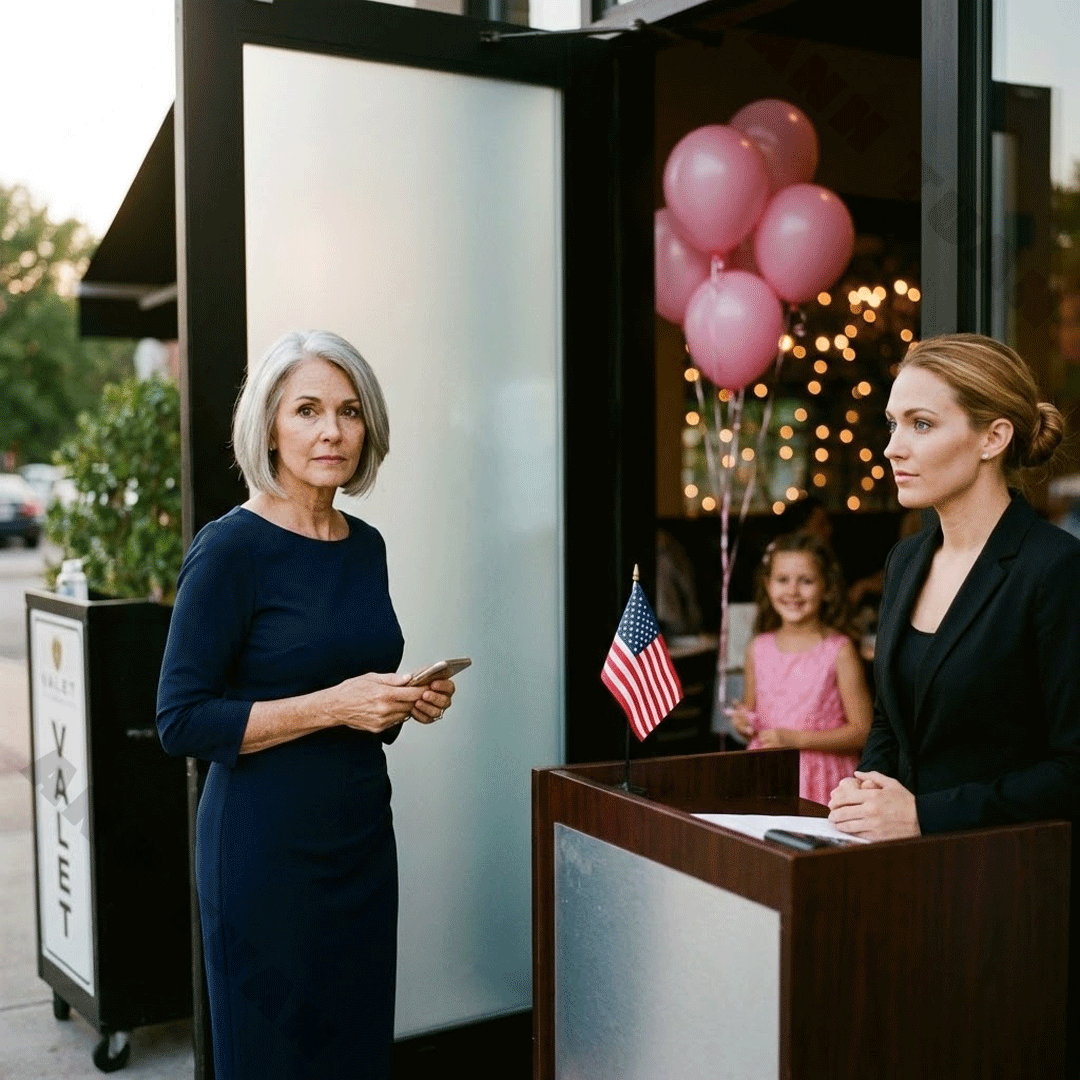

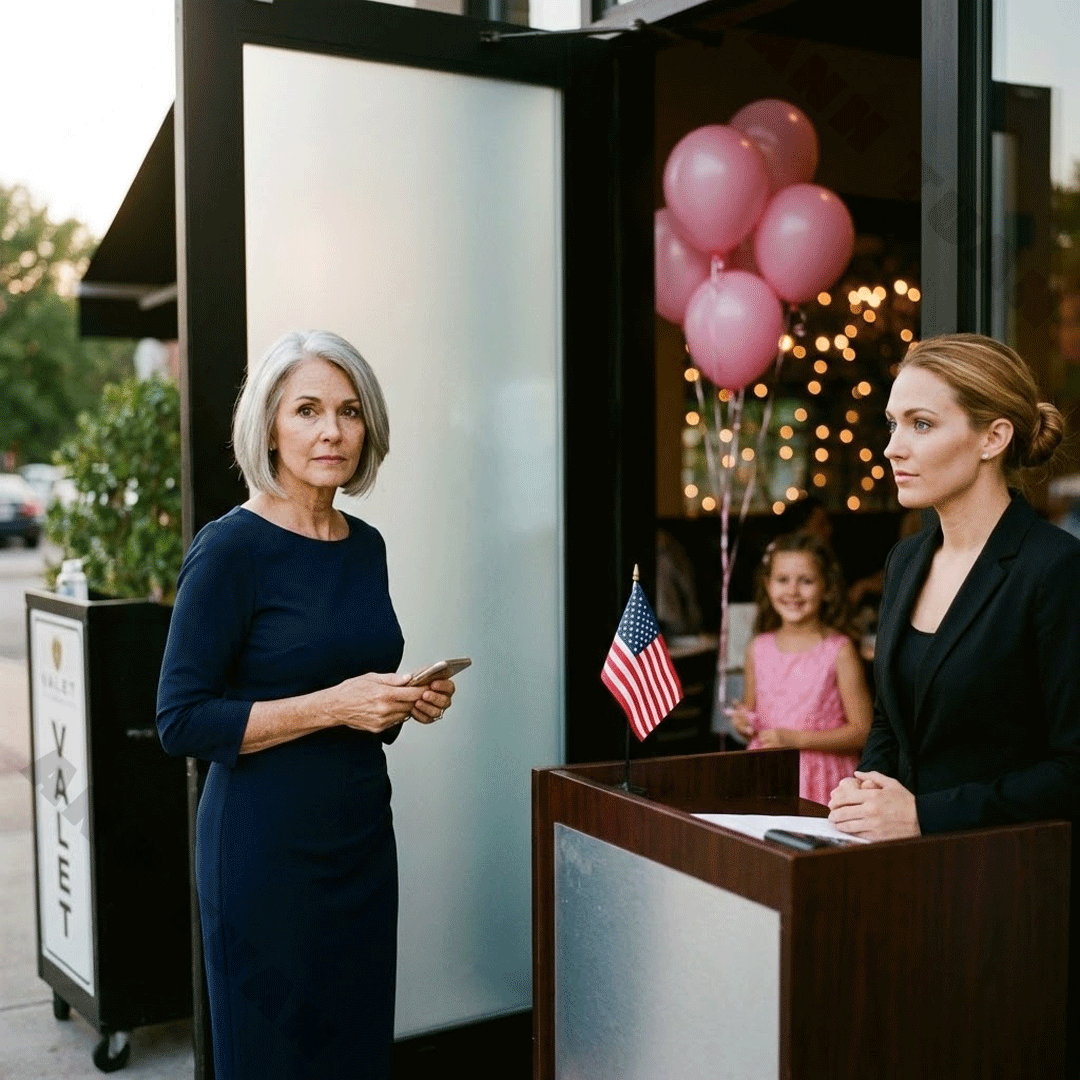

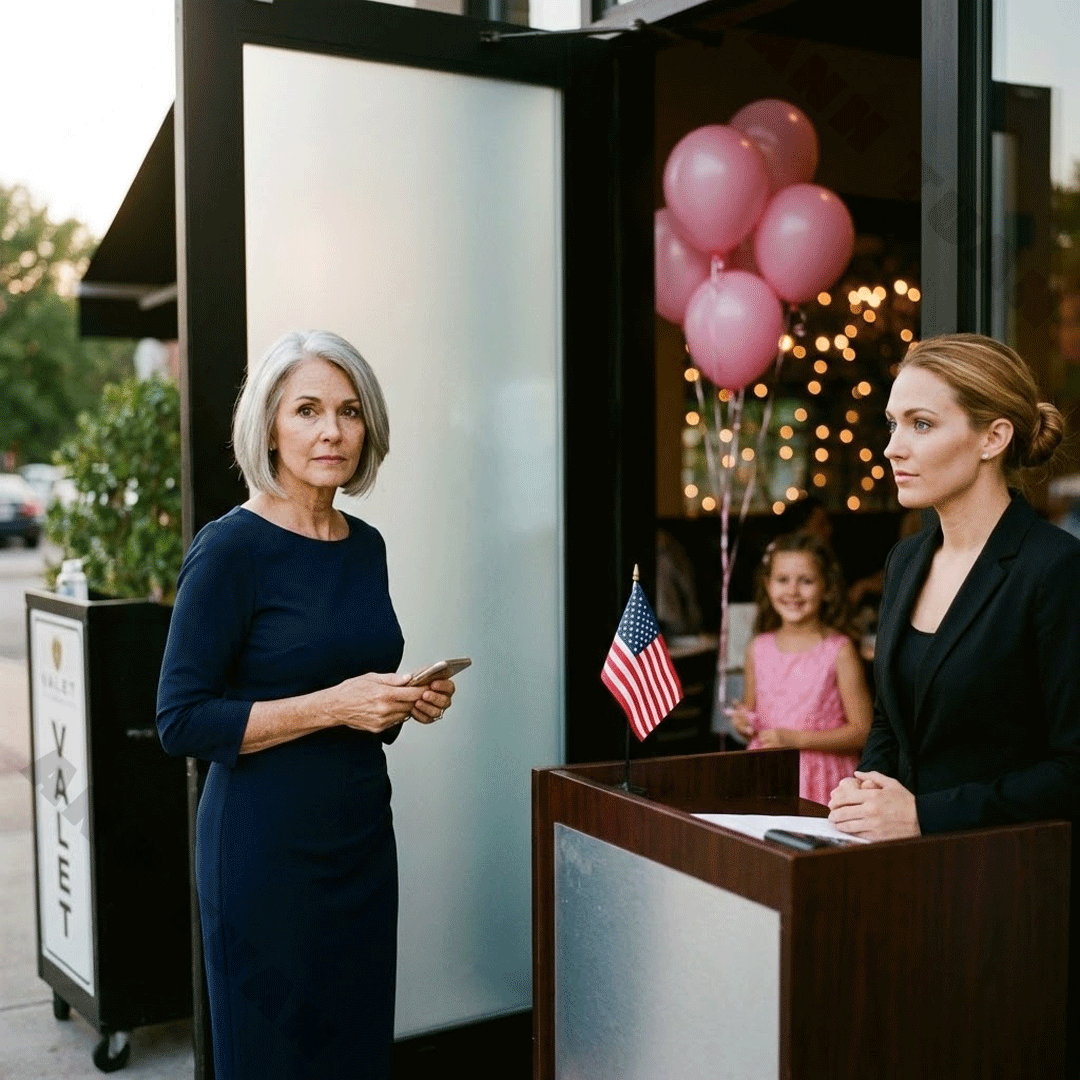

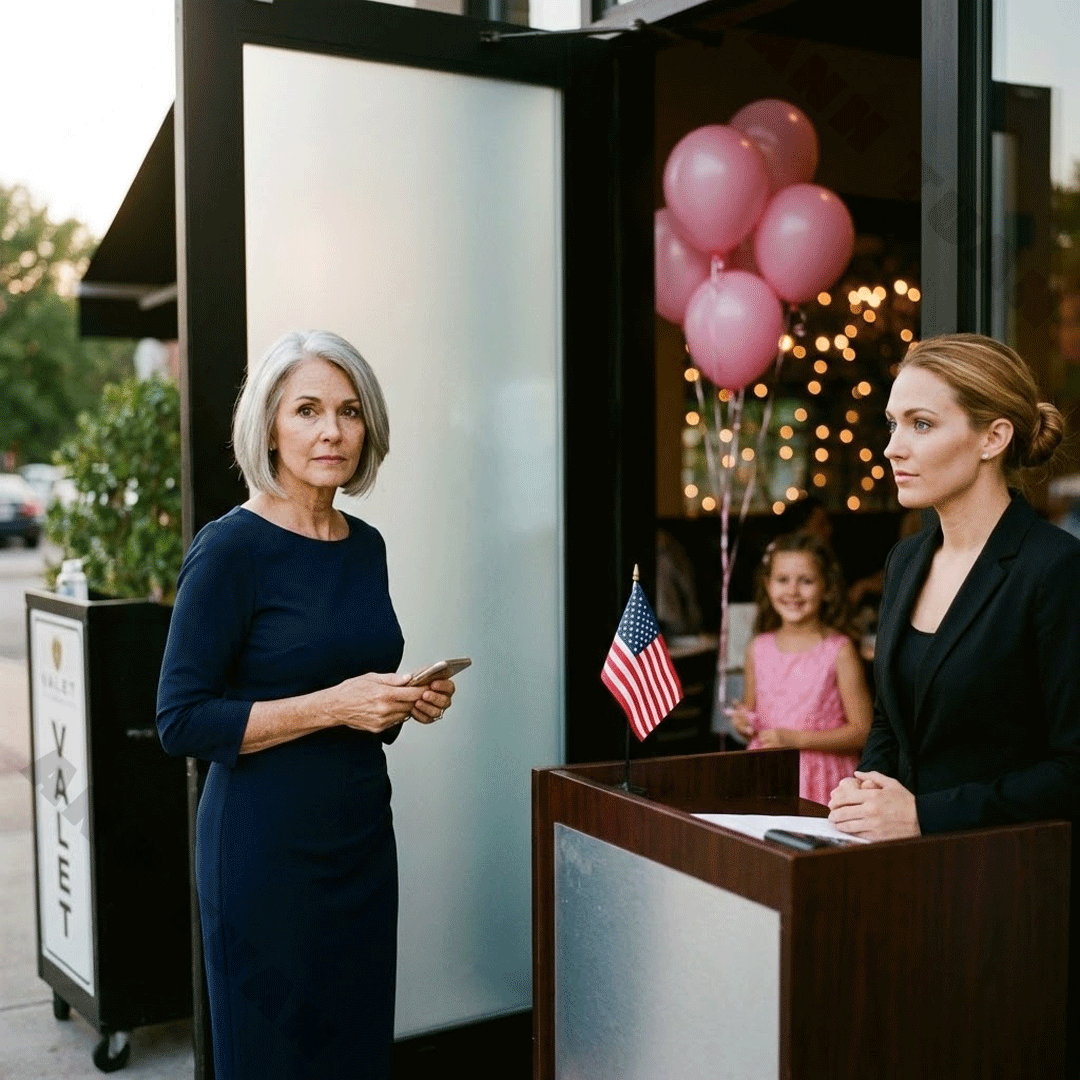

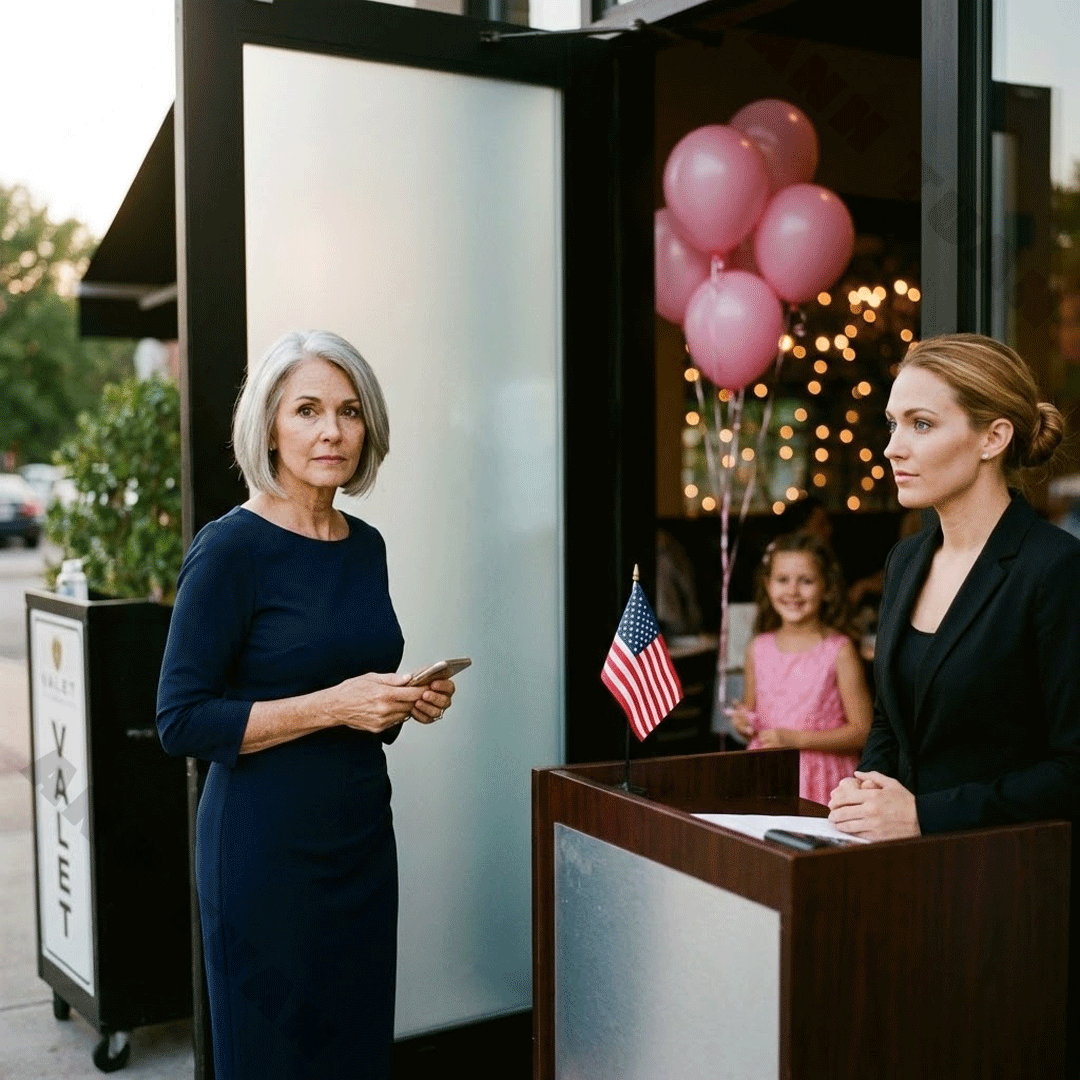

When I arrived at my granddaughter’s birthday dinner at the restaurant, the hostess leaned in and quietly said, “I’m sorry… your name isn’t on the reservation list.”

For a second I honestly thought I’d misheard her. You know how a place gets loud even when it’s “nice,” how everything echoes off the marble and glass and those big fake-quiet chandeliers? My brain tried to make her sentence into something else, like maybe she meant the valet list, or the waitlist, or the “we’re running behind” list.

But then she looked down at her clipboard again, the way people do when they’re about to repeat bad news, and she said it one more time, softer, like if she lowered her voice enough it would hurt less.

“I’m sorry, ma’am. Your name isn’t on the reservation list.”

I froze, because I’d quietly paid five thousand dollars to make sure tonight went smoothly. Five thousand dollars. Not a little gift card. Not a cute envelope with cash. A real check, with a memo line I’d filled in carefully like an idiot who still believes a memo line is a kind of proof.

I didn’t argue. I didn’t make a scene. I didn’t march into the room waving my arms like some reality show villain. I just stood there, the way you stand when your body hasn’t caught up to the fact you’ve been humiliated.

I stared at the hostess, then past her shoulder through the glass doors of the private dining room.

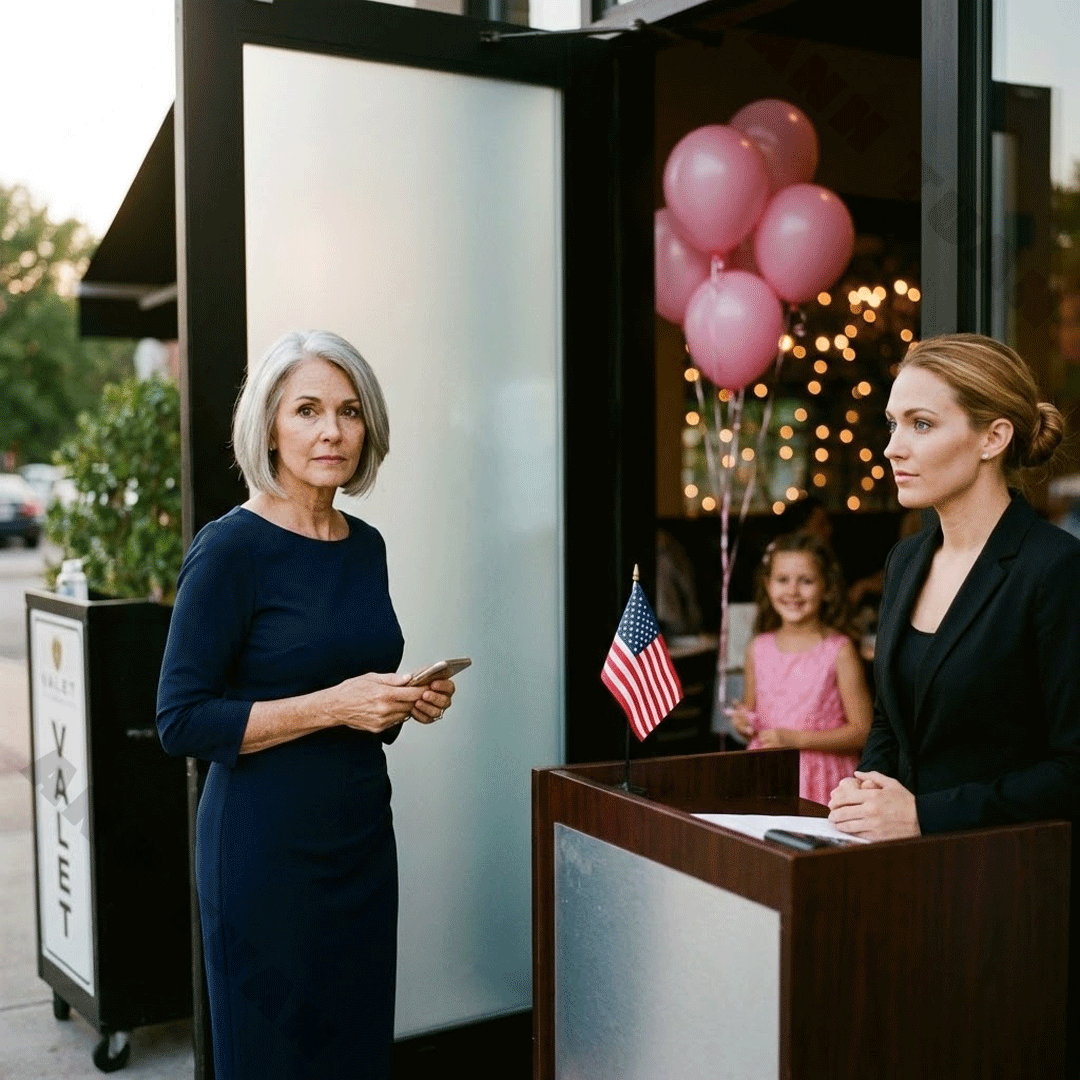

The room was called the Marshall Room, which always made me smile because it sounded fancy in a way that tried too hard, but Marello’s had been like that since the renovations. Warm lighting, dark wood, crisp white tablecloths, and those framed black-and-white photos of the city from decades ago. If you grew up around here, you recognized a few of the streets and old storefronts. If you didn’t, it just looked “classy” in that generic, polished way.

Inside I could see my granddaughter, Lily, in her pink birthday dress, the kind with a tulle skirt that makes a little girl look like she’s floating. She had her hair curled and pinned on one side with a sparkly clip. She was eight today. Eight. She was standing near a balloon arch that screamed “Pinterest Mom” in pastel letters, surrounded by at least sixty people.

At least sixty.

Most of them I’d never seen before in my life.

They were dressed the way people dress when they want you to know they belong. The men in tailored jackets with pocket squares they probably didn’t fold themselves. The women in sleek dresses and layered gold necklaces, hair blown out into soft waves, the kind of effortless that takes an hour and a professional.

I could see the head table, too. My daughter, Jennifer, sitting beside her husband, Derek, and his parents. Derek’s mother, Patricia, had a posture that could have been carved out of marble. Derek’s father sat with that relaxed, satisfied look men get when they’ve never had to wonder whether they’ll be taken seriously in a room.

The hostess cleared her throat in that polite way. “I’m sorry, ma’am,” she repeated, glancing down. “The party is at capacity. Mrs. Barrett was very specific. Sixty guests only, and you’re not on the list, Mrs. Barrett.”

Mrs. Barrett.

That part landed weirdly, too, like a second insult slipped in for free. My last name isn’t Barrett. It’s Hayes. It’s been Hayes my whole life, even through my marriage, even after my husband died. I kept it because it was mine and because changing it again felt like erasing something I wasn’t ready to erase.

But Jennifer had gone back to using her married name exclusively about six months ago, right around the time her husband got that promotion to senior partner at his law firm. It wasn’t subtle. Suddenly every holiday card was “The Barrett Family.” Every email signature was “Jennifer Barrett.” And when she introduced herself on the phone, you could hear her smile through the words, like the name came with a better zip code attached.

“I’m Lily’s grandmother,” I said quietly.

The words felt thick in my throat, like they had to push past something swollen and tender. I didn’t say it loudly. I didn’t say it like a challenge. I said it like a fact that should have cleared everything up, because in my mind there were still certain facts that mattered, certain roles you didn’t just delete with a clipboard.

The hostess’s eyes widened slightly. Her professional smile faltered. She looked uncomfortable now, like she’d just realized she was the person assigned to deliver the blow.

“Oh,” she said, and she glanced toward the glass doors again, then back at me. “I… let me get Mrs. Barrett for you.”

I stood there in the marble foyer of what used to be my favorite Italian restaurant, the place where Jennifer and I had celebrated every milestone in her life. Her college acceptance. Her engagement. The day she told me she was pregnant with Lily, her hands shaking around a glass of water like it was the most fragile thing in the world.

This was the place where we’d taken pictures on the front steps in winter coats, laughing, cheeks pink from the cold. The place where Marco, the manager, used to slip Jennifer an extra tiramisu slice and tell her she had her mother’s eyes. Back then, when we came in, it felt like being known.

Tonight, I felt like a stranger in a dress I’d bought specifically to not look like a stranger.

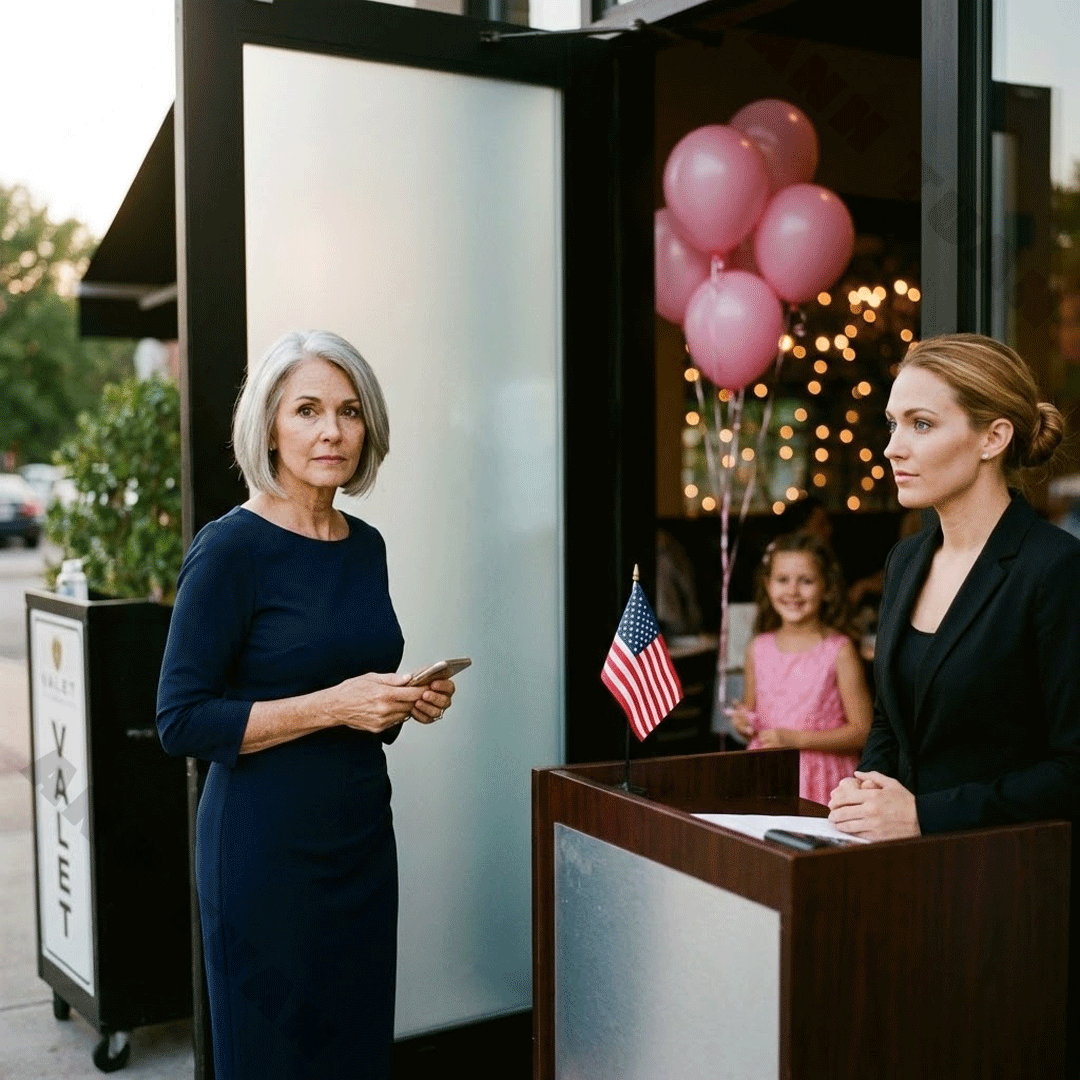

I was wearing navy, simple and elegant, and I’d bought it last month, the day Jennifer and I went shopping together. She’d stood in the fitting-room doorway and said, “Mom, that one makes you look so elegant,” like she was giving me permission to appear in her life without embarrassing her.

That shopping trip felt like it had happened in another lifetime now. Like it belonged to a version of me who still thought proximity meant closeness.

Through the glass, I watched the hostess weave between tables. She moved carefully, like she was walking through someone else’s dream. She finally stopped at the head table where Jennifer sat next to Derek and his parents. She leaned down and whispered something near Jennifer’s ear.

Jennifer’s face went pale.

Derek’s expression didn’t change at all. He didn’t even blink the way Jennifer did, that quick panic blink. He just took a sip of wine, calm as a man watching a storm pass over someone else’s house.

Jennifer stood up slowly, smoothing down her cream-colored dress.

That dress. The one I’d helped her pick out with the money I’d given her for party expenses. She’d sent me photos of three different options, and I’d told her the cream one looked classy and soft and like her. “Classy,” I’d said, because that’s the word she likes, the word she repeats like a prayer.

She pushed through the glass doors, and I noticed she didn’t quite meet my eyes.

“Mom,” she said. “Hi.”

Then she winced, and her voice dropped. “This is… this is awkward.”

Awkward.

That was the word she chose. Not “Mom, what are you doing out here?” Not “I’m so sorry.” Not even “Let’s fix this.” Just awkward, like I’d shown up wearing the wrong shoes, like I’d accidentally RSVP’d to the wrong event, like my presence was an inconvenience she needed to manage quietly before it disrupted the atmosphere.

“I gave you five thousand dollars for this party,” I said.

My voice came out steadier than I felt. Inside I was shaking so hard I could feel it in my teeth, but my voice stayed calm, almost polite. That’s what thirty years of nursing does to you. You can be bleeding inside and still sound like you’re asking about someone’s allergies.

“The check cleared three days ago,” I continued. “And I’m not on the guest list.”

Jennifer’s perfectly manicured hands twisted together like she was trying to wring an answer out of her fingers.

“It’s just,” she started, and then stopped, because she didn’t have a good way to say it. She tried again. “Derek’s parents invited so many people from the firm, and we had to keep the headcount at sixty because of fire code and… and…”

“And I was the one you cut,” I said.

It wasn’t a question. It came out as a sentence that had settled into place all by itself.

She finally looked at me. And in her eyes I saw something I’d never seen before. Shame, yes. But also something harder, like a wall that had been built brick by brick, and now she was standing behind it.

Resentment, maybe.

“Derek’s parents are paying for Lily’s private school,” she said, like she was listing facts in a courtroom. “They bought us the house in Riverside Estates. They’re setting up a trust fund for her college. What were you able to offer, Mom?”

The words landed like a slap.

What was I able to offer?

Just thirty-four years of raising her alone after her father left. Just working double shifts at County General so she could have the childhood I never did. Just coming home with sore feet and a headache and still making her grilled cheese at midnight because she had a science project due and forgot to tell me until the last minute.

Just taking out a second mortgage to help with her wedding because Derek’s family thought a budget wedding was embarrassing.

Just the fifteen thousand I’d deposited into a separate education fund for Lily, the one Jennifer didn’t know I’d been building for three years, dollar by dollar, sometimes from my retirement savings, sometimes from those little extra shifts I took even when my back begged me not to.

I stared at Jennifer and felt something in me shift. Not explode. Not shatter. Shift. Like a door clicking into place.

“I see,” I said quietly.

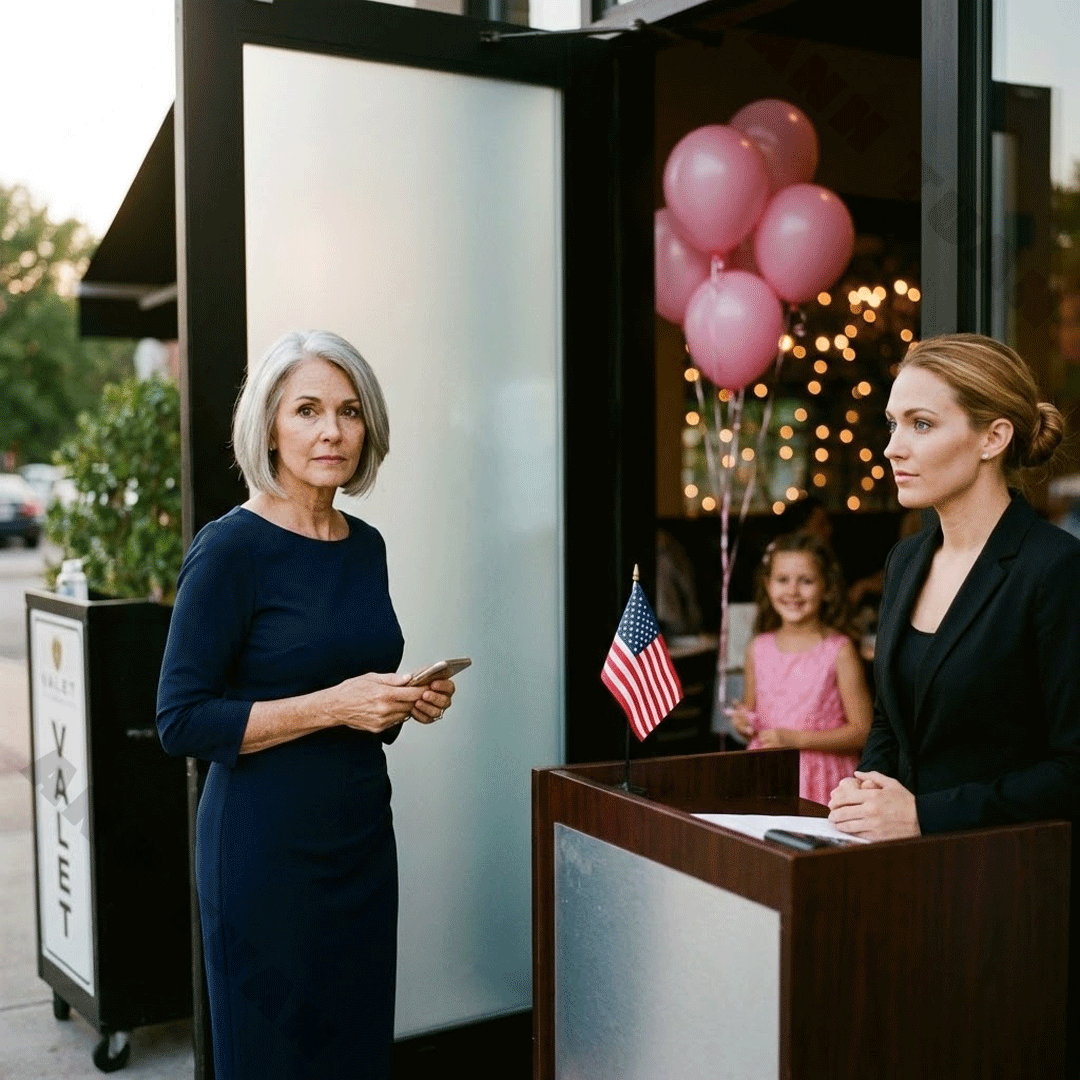

Behind her, Derek appeared, sliding into position the way men like him do, as if the space beside my daughter belonged to him by default. He placed a hand on her shoulder, possessive but subtle, like he wanted to look supportive while still making sure everyone knew who was in charge.

“Victoria,” he said, and he smiled, his mouth polite, his eyes flat. “This is really about the children, not the adults. We wanted to keep the party intimate, focused on Lily’s actual social circle. Her classmates from Riverside Academy, families from the country club. I’m sure you understand.”

Riverside Academy. The country club.

I looked at this man my daughter had married, in his perfectly pressed suit, his expensive watch catching the light, his voice set to calm-and-reasonable. And I understood everything with sudden, painful clarity.

I was an embarrassment.

The retired nurse from the modest neighborhood. The woman who still drove the same Honda Civic from 2010 because it ran fine and because I didn’t feel like a car note was a personality upgrade. The woman whose house needed new gutters and whose kitchen cabinets were original from 1985. The woman who still clipped coupons sometimes and bought Earl Grey that was “too fancy” according to her daughter.

Derek’s parents, with their vacation home in Aspen and their Mercedes in the driveway, fit. They belonged in this room full of people who believed money was the same thing as worth.

I didn’t.

“Mom,” Jennifer whispered, glancing back nervously at the party. Through the glass I could see Patricia watching us, her expression carefully neutral, like a woman studying a situation without getting her hands dirty. “Please don’t make a scene.”

“I won’t make a scene,” I said.

And I meant it. I wasn’t going to shout. I wasn’t going to cry in front of their guests. I wasn’t going to give Derek the satisfaction of painting me as emotional, irrational, dramatic. I’d spent too much of my life being the calm one.

I reached into my purse and pulled out my phone, the one Jennifer always commented on, saying I needed to upgrade to the newest model, like my phone was an extension of my social rank.

“I just need to make a quick call,” I said.

“Mom, but…” Jennifer started.

I was already walking away toward the restaurant’s main entrance, my heels clicking on the marble floor. I heard Derek behind me, not even bothering to lower his voice enough.

“She’ll get over it,” he said.

She’ll get over it.

Those five words rang in my ears as I pushed through the heavy front doors into the warm May afternoon. The sun hit my face like a slap of reality. Cars rolled past on the street. A couple walked by holding hands, laughing at something on a phone screen. Somewhere a dog barked, and everything sounded normal, like my world wasn’t tilting.

She’ll get over it.

How many times had I swallowed my hurt and told myself it wasn’t worth a fight? How many times had I made myself smaller, quieter, more convenient so Derek wouldn’t see me as a problem?

When Derek “forgot” to invite me to their housewarming party.

When Jennifer stopped calling as much, stopped visiting unless she needed something.

When they started spelling Lily’s last name with Derek’s family’s archaic spelling, Barrett instead of Barret, to match some ancestor I’d never heard of. Jennifer had laughed about it like it was charming, like history was a cute accessory.

I stood on the sidewalk outside Marello’s watching families walk past, children laughing, couples stepping around each other like they were dancing. Somewhere inside, my granddaughter was turning eight years old, and I wasn’t there.

I opened my phone and pulled up my banking app.

The five-thousand-dollar check to Jennifer showed as pending.

I’d written it two weeks ago for Lily’s birthday celebration, the memo line said. Jennifer had deposited it immediately, like she couldn’t wait to claim it.

My hands shook as I navigated to the stop-payment option.

A little warning box popped up, asking me if I was sure, reminding me of the fee, reminding me of the consequences, like the bank was trying to do what Jennifer hadn’t done: make me pause.

“Yes,” I whispered, to no one.

Five thousand dollars would be back in my account within forty-eight hours, minus the thirty-five-dollar fee. I’d never cared less about thirty-five dollars in my life.

And then I did something I’d been putting off for weeks. Not because I didn’t know what to do, but because doing it made it real.

I called my financial adviser, Thomas Brennan.

Tom had been handling my modest investments since my husband passed fifteen years ago. He wasn’t a flashy advisor with billboards and a slick smile. He was steady. The kind of man who remembered your dog’s name and didn’t treat a small portfolio like it wasn’t worth his time.

He answered on the second ring.

“Brennan Financial.”

“Tom,” I said. “It’s Victoria Hayes. I need to make a change to the education fund I set up.”

There was a beat, the mental file opening on his end.

“Of course, Victoria,” he said. “The one for your granddaughter. We just crossed fifteen thousand last quarter with the growth.”

“That’s the one,” I said. My voice sounded strange, like it belonged to someone older. “I need to change the beneficiary structure. Make it a trust with myself as the trustee. Jennifer can’t access it directly.”

Silence, then a quiet exhale.

Tom had known me long enough not to ask questions right away. But I could hear the concern in his voice anyway, threaded through his professionalism.

“That’s absolutely doable,” he said. “I’ll draft the paperwork. Are you all right?”

I looked back at the restaurant doors. For a moment I imagined Lily’s face when she didn’t see me. I imagined her little hands, sticky from frosting, reaching for mine in the way she always did when she wanted me close.

“I’m learning to be,” I said.

“Okay,” Tom said, and I could tell he meant it the way nurses mean it, like he was taking my vitals through the phone. “I’ll get it moving today.”

I ended the call and stood there for a second, phone warm in my hand, my heart still thudding like it was trying to climb out of my chest.

The second call was harder, not because I didn’t know what to do, but because it involved a person. A human being I liked. Someone who would hear the crack in my voice if I let it slip.

I pulled up Marco Antenelli’s personal cell.

Not Marello’s main number. Marco’s number.

Marco had been the manager here for twenty years. I’d known him since Jennifer was in high school and we’d come here for her sixteenth birthday. He’d watched Jennifer grow up in the way restaurant people do, by seeing you once a month, once every holiday, and still remembering your story.

We’d bonded over his mother’s decline from Alzheimer’s. I’d given him advice about care homes, sat with him in the parking lot when she passed, letting him cry because no one else was going to sit with him like that.

He picked up immediately.

“Victoria,” he said, warm and familiar. “Are you here for the party? I’ve got something special planned for the birthday girl.”

My throat tightened. I swallowed.

“Marco,” I said. “I need you to do something for me. It’s about the payment for the party.”

There was kitchen noise in the background, the clatter of pans, someone calling “corner” like a warning. I could picture him in his office, sleeves rolled up, pen behind his ear.

“The deposit?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Jennifer paid half. The balance is due at the end, right?”

“That’s correct,” Marco said. “We were set.”

“The deposit was my check,” I said. “And I’m stopping payment on it.”

Silence.

Then, quietly, like he didn’t want anyone nearby to hear, “Victoria. What happened?”

I told him. Not the long version, not every wound I’d ever swallowed, but the bones of it.

I wasn’t on the guest list. Derek’s comment. Jennifer’s words about what I could offer.

Marco exhaled slowly. I could picture him running a hand through his silver hair the way he did when he was angry but trying to stay calm.

“I wish I could say I’m surprised,” he said. “I noticed how they placed you… actually, they didn’t include you in the seating chart at all. I thought it was an oversight.”

“It wasn’t,” I said.

“What do you want me to do?” he asked, and now his tone shifted into business, solid and protective at the same time. “Your contract says deposit is nonrefundable if canceled day-of. But if there’s a payment issue, service stops immediately.”

His voice was firm.

“Victoria,” he added, softer. “Are you sure? This is your granddaughter’s birthday.”

“My granddaughter,” I said, and I felt something sharp in my chest, “who I’m not allowed to celebrate with.”

I closed my eyes, breathing in the warm air, exhaust and spring flowers and the faint smell of garlic drifting out when the doors opened.

“I don’t want to ruin her day, Marco,” I said. “I just… I can’t pay for a party I’m not welcome at. I can’t keep paying to be treated like I’m not enough.”

There was another pause, then I heard a chair scrape, like he’d stood up.

“You know what,” Marco said. “Forget the legalities. You’ve been a customer here for twenty years. You held my hand at my mother’s funeral. If you’re not welcome at this party, then neither is my restaurant’s service.”

“Marco,” I started, startled.

“I’ll tell them there’s a payment issue,” he continued. “We need to suspend service until it’s resolved.”

“You don’t have to,” I whispered, because some part of me still wanted to be reasonable, still wanted to protect everyone else from consequences.

“I know I don’t have to,” he said. “I want to. Some things are more important than money.”

He paused again. “Where are you now?”

“In the parking lot,” I said.

“Go home, Victoria,” he said. “Take care of yourself. And maybe stop answering the phone for a while.”

I didn’t realize I was crying until I tasted salt. I wiped my cheek quickly, annoyed at myself, as if tears were a failure I could chart and correct.

“Thank you,” I said.

“You don’t have to thank me,” he replied. “Just go.”

I drove home in a daze.

My little two-bedroom house on Maple Street looked exactly as it had for thirty years. The same garden gnome Jennifer had given me when she was ten, crooked smile and chipped paint. The same rose bushes I’d planted when my husband was still alive, when our hands were still strong enough to dig holes without aching for days after. The same crack in the driveway I kept meaning to fix.

For the first time in years, I didn’t see it as inadequate.

I saw it as mine.

The calls started twenty minutes after I got home.

First Jennifer, then Derek, then three calls from numbers I didn’t recognize, probably the restaurant or Derek’s parents or someone from his law firm who thought they could intimidate a retired nurse with a good credit score.

I let them all go to voicemail.

I made myself a cup of tea. Earl Grey, my favorite, the fancy kind Jennifer always said was a waste of money. I sat in my reading chair by the window and watched the late-afternoon light shift across the living room carpet, calm and steady like it didn’t care about my daughter’s social calendar.

My phone buzzed again. And again.

I didn’t pick it up.

The doorbell rang as the sun was starting to set.

I almost didn’t answer. But some habit, some ingrained politeness, that old reflex of “someone is at the door, so you open it,” made me get up.

When I opened the door, I actually blinked, because my brain needed a moment to accept what my eyes were seeing.

Patricia Barrett stood on my porch.

Derek’s mother.

In all the years Jennifer had been married, Patricia had been to my house exactly twice. And both times she’d commented on something. The outdated light fixtures. The small television. The lack of a home security system, said in that tone like she was concerned for my safety but really she was concerned for my status.

Tonight, she stood there without a smile, without her usual bright social mask. She was dressed impeccably, of course, hair perfect, handbag probably worth more than my car. But her face looked… unsettled. Not guilty. Not exactly. Just pulled tight, like someone who’d been forced to acknowledge something ugly.

“May I come in?” she asked.

I stepped aside, too surprised to refuse.

Patricia walked into my living room, and for once, she didn’t comment on anything. She didn’t glance at the thrift-store lamp. She didn’t look at the family photos on the mantle like she was assessing them.

She just turned to face me, designer handbag clutched in front of her like a shield.

“What happened at the restaurant was wrong,” she said.

I blinked.

Whatever I’d expected, it wasn’t that.

“I didn’t know you weren’t on the guest list until I saw you at the door,” she continued. “I asked Jennifer about it afterward while Derek was… dealing with the restaurant situation.”

Her voice tightened on the words “restaurant situation,” like she was still processing the embarrassment of it, the way people from their world process problems. Not as pain. As public perception.

“She told me,” Patricia went on, “that you’d agreed not to come because you were feeling unwell.”

The lie was so casual I almost laughed, and then the laughter turned into something bitter that stayed stuck behind my ribs.

“I was never told about the party,” I said quietly. “Jennifer took my five-thousand-dollar check for it two weeks ago.”

Patricia’s face went white.

She lowered herself slowly onto my couch, that expensive bag sliding to the floor like she’d forgotten it existed.

“Oh God,” she whispered.

We sat in silence for a moment. From somewhere outside, I could hear children playing, a dog barking, a car door slamming, normal life continuing while mine felt like it had split open.

Finally Patricia looked up at me, and for the first time, her eyes held something real.

“This is Derek’s doing,” she said. “Jennifer was never like this before.”

“Jennifer made her own choices,” I said, because I couldn’t let my daughter off the hook entirely, not even in my pain.

“Yes,” Patricia said quickly, nodding. “Yes, she did. But Derek… Derek has been steering this. And I’ve been letting him.”

She took a breath like it hurt.

“I owe you an apology,” she said. “Several apologies. We’ve been… I’ve been making you feel less than. Small. Unimportant. Because you don’t have what we have financially.”

She looked around my living room then, not with judgment, but with something like recognition. Like she was finally seeing that a home could be modest and still be a life, still be a story.

“But you raised a daughter who became a surgical nurse,” she continued, voice quieter. “You bought a home and kept it for thirty years. You worked every day of your adult life, and we’ve treated you like you’re an embarrassment.”

“…I supplied,” I said, and my voice stayed calm, because what else could I do. “Like I’m something to hide.”

Patricia flinched.

“Yes,” she whispered.

I crossed my arms, feeling tired all the way down to my bones. “Why are you telling me this?”

“Because what happened at the restaurant was the final straw,” Patricia said.

She picked up her bag again, opened it, and pulled out her phone. Her hands were steady, but her mouth trembled slightly, like she was doing something she didn’t do often.

“I’m showing you this because I think you should know what you’re dealing with,” she said.

She turned the phone toward me.

It was a text thread between Derek and Jennifer.

Derek: Did you handle the guest list situation?

Jennifer: Yes. I told the restaurant my mother wasn’t coming. Too many people from your firm.

Derek: Good. Mom asked if your mother would be there. I said you two weren’t close. Keep it that way.

The texts continued.

Plans to “phase out” visits with me.

Derek’s comments about my house being depressing, about how they needed to limit Lily’s exposure to “lower expectations.”

Jennifer’s agreement, though her texts were shorter, less enthusiastic, like she was typing with one eye on the edge of her conscience.

And then at the bottom, from this afternoon:

Derek: Restaurant is threatening to stop service because of a payment issue with your mother’s check. Can you believe this? She’s trying to ruin Lily’s birthday out of spite.

Jennifer: I’ll handle it. She’s always been dramatic.

I handed the phone back.

My hands weren’t shaking anymore.

I felt oddly calm, like something had crystallized inside me, sharp and clean. The kind of clarity that comes when the last thread of denial snaps.

“I’m not showing you this to hurt you more,” Patricia said quickly, her voice strained. “I’m showing you because you need to know it’s not going to get better. Derek will keep pushing you out, and Jennifer will let him because she’s afraid of losing the life he’s given her.”

“Why are you doing this?” I asked. “He’s your son.”

Patricia’s jaw clenched. “He’s my son and I love him,” she said. “But I don’t like who he’s become.”

She stood up, as if sitting had made her feel too exposed.

“He learned it from his father,” she added, almost like she was confessing. “This need to control everything. To measure everyone’s worth by their bank account. I went along with it for too long.”

She walked to the door, then turned back.

“The party ended badly, by the way,” she said, and something flickered across her face that might have been shame. “Once the restaurant stopped service, people started leaving. Lily was crying. Derek was furious.”

Her lips pressed together.

“Jennifer looked… hollow,” she finished. “Like she’d finally seen what she’d become and couldn’t face it.”

Then Patricia left, and the house felt strangely quiet after the click of the door, like the walls were holding their breath.

I sat in the growing darkness of my living room for a long time.

My phone buzzed constantly, but I didn’t look at it.

I just stared at the family photos on my mantle. Jennifer at five with her missing front tooth, grinning. Jennifer at seventeen in her graduation cap, eyes bright. Jennifer at thirty holding newborn Lily, exhausted and smiling like she’d just discovered a new universe.

And I thought about the last eight years since Derek had entered our lives. How gradual it had been. So gradual I hadn’t noticed.

I’d been erased.

Not with one big dramatic fight, but with a thousand small edits. A dinner here I wasn’t invited to. A holiday plan made without me. A conversation where my opinion wasn’t asked. A joke at my expense I was expected to laugh at.

And the worst part was realizing how often I’d helped them do it by swallowing my own hurt.

That night, I didn’t call anyone. I didn’t cry again. I didn’t answer the phone.

I just went to bed early in my small house on Maple Street, and for the first time in a long time, I didn’t feel guilty for putting myself first.

The next morning, I woke up and did something I hadn’t done in months.

I called my friend Susan.

Susan and I worked together at County General for twenty years. We did night shifts and holiday shifts, the kind where you miss Christmas mornings and make up for it later with cold leftovers and a tired laugh. Susan was the one who brought me casseroles when my husband died, the one who sat with Jennifer at the funeral when Jennifer’s hands wouldn’t stop shaking. She’s blunt, funny, and loyal in a way that doesn’t require announcements. The kind of friend who will tell you you’re being ridiculous and then show up anyway.

I’d stopped seeing her because Jennifer said she was “negative.” Which, looking back, is one of those words people use when they mean “she tells the truth and I don’t like it.”

Susan picked up on the first ring.

“Victoria?” Her voice jumped up an octave. “Oh my God. Where have you been? I’ve been so worried about you.”

The concern in her voice cracked something in me. I leaned against my kitchen counter and stared at the little crack in the tile I’d always meant to fix.

“I’ve been… around,” I said, and my voice sounded smaller than I wanted.

“No,” Susan said immediately. “Don’t ‘around’ me. You’ve been ghosting. Even your Christmas card last year felt weird. Like it was written by a PR team.”

I let out a small, surprising laugh. It came out rough.

“I need to tell you something,” I said.

“Good,” she replied. “Tell me everything.”

So I did.

I told her about the party, the hostess, the guest list, the way Jennifer said “awkward” like it was my fault. I told her about Derek’s comment. I told her about the stop payment and the call to Tom and Marco. I told her about Patricia showing up with the texts, and the lines that kept replaying in my head like a cruel song.

When I finished, Susan didn’t speak for a moment. I could hear her breathing, slow and angry, the way it gets when she’s trying not to explode.

“Come over,” she said finally.

“Susan ”

“Nope,” she cut me off. “Come over right now. Frank is making his famous Sunday pancakes and we’re not taking no for an answer.”

I almost said no out of habit. I could feel the reflex rising like muscle memory. I almost told her I didn’t want to be a bother, that she didn’t have to, that I was fine.

But I wasn’t fine. And I was tired of pretending I was.

“Okay,” I said, and it came out like a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding.

“That’s my girl,” Susan said, and her voice softened. “And Victoria? Don’t put on your ‘I’m fine’ face. I want the real one.”

I drove to Susan’s house across town, the one with the peeling paint and the loud wind chimes and a porch swing that squeaks when you sit down. The kind of house Derek’s mother would call “charming” in a tone that meant “sad.”

Susan met me at the door before I could even knock.

She didn’t ask permission. She didn’t tiptoe. She pulled me into a hug so tight I felt my ribs protest.

“Oh, honey,” she said into my hair. “Oh, Victoria.”

Inside, Frank was at the stove flipping pancakes like it was an Olympic sport. He gave me a warm smile and said, “You hungry?” like that was the only question that mattered. Like food and kindness were the simplest forms of love.

I sat at Susan’s worn kitchen table, the one covered in little scratches and burn marks from a life being lived, and for the first time in a long time I laughed. Really laughed. Not the polite laugh. Not the “I’m fine” laugh. The kind that surprises you because you forgot your body could do it.

Susan didn’t let me spiral. She didn’t let me make excuses. She let me talk, and then she pulled me back with blunt little truths.

“You’re not crazy,” she told me, stabbing a piece of pancake with her fork like it was Derek’s ego. “You’re not dramatic. You’re not ‘too sensitive.’ You were being used.”

I flinched at that word, even though I knew it was true.

“And your daughter,” Susan continued, softer now, “your daughter is not a child. She made choices. But I’m telling you, Victoria, that man has been poisoning her brain for years.”

I stared at the syrup glistening on my plate, thinking about all the times Jennifer had sounded like Derek without realizing it. All the times she’d said “we” when she meant “he.”

Susan reached across the table and squeezed my hand.

“You don’t have to earn your place,” she said. “You don’t have to pay for it. And you don’t have to keep bleeding just because you’re used to it.”

When I left Susan’s house, my chest felt lighter. Not healed. Not fixed. But lighter, like I’d finally let fresh air into a room that had been sealed for too long.

Back home, my phone had a mountain of voicemails.

I didn’t listen.

I watered my roses. I made myself lunch. I sat on my back step with a glass of iced tea and listened to the neighborhood sounds, the ordinary ones. A lawn mower. A kid on a bike. A neighbor’s radio playing something old and cheerful.

And then, three days later, Jennifer showed up at my door.

She looked terrible.

No makeup. Hair in a messy ponytail. Eyes red from crying. She was alone.

For a moment, I didn’t move. I just stood there looking at her through the screen door like she was a stranger.

“Mom,” she said, voice small. “Can I come in?”

I should have said no. I felt the part of me that wanted to protect myself rise like a guard dog.

But I also saw something in her face I hadn’t seen in a long time: fear, real fear, not the kind that comes from social embarrassment, but the kind that comes from realizing you’ve done something you can’t undo.

I opened the door and stepped aside.

She walked in like she didn’t know where to put her hands.

She sat on the same couch where Patricia had sat, but she didn’t have Patricia’s composure. She didn’t have the armor of money and pride.

She broke down within seconds.

“I’m sorry,” she sobbed, hands covering her face. “Mom, I’m so sorry. I don’t… I don’t know what happened to me.”

I stood there watching her cry, and something complicated moved through me. Love, yes. Anger, yes. Exhaustion, mostly.

“Derek kept saying we needed to fit in,” she continued, words tumbling out. “With his colleagues, with his family’s social circle, and you just… you didn’t fit. And instead of telling him that was insane, that you’re my mother and you’ve given me everything, I just… I went along with it.”

She looked up at me with wet eyes.

“And then it became easier to go along with it than to fight it,” she whispered. “And then I started believing it.”

I didn’t rush to comfort her. I didn’t pat her back. I didn’t do the soothing sounds I used to do when she was little.

I just waited.

Because for once, I needed her to sit in it. I needed her to feel the weight of what she’d done.

“The party was a disaster,” she said finally, wiping her face with the back of her hand like she didn’t even care about smearing mascara because she hadn’t worn any. “Lily figured out you weren’t there. And when she asked why, Derek said you were busy, but she knew he was lying. She’s eight, but she’s not stupid.”

My throat tightened. I pictured Lily’s little face, that sharp intelligence she got from Jennifer’s side, the way she studies people.

“She stood up in front of everyone,” Jennifer continued, voice shaking, “and she said, ‘This isn’t a real party if Grandma’s not here.’ And then she refused to blow out the candles. And then the restaurant stopped serving food.”

Jennifer swallowed.

“And Derek’s colleagues started leaving,” she said. “They acted polite, but I could tell they were judging us. They were judging him. And his mother…”

She broke again.

“His mother told him he was an embarrassment to the family. In front of everyone.”

I thought I would feel satisfaction hearing that. I thought it would feel like justice, like a payoff.

But mostly I just felt tired.

“What do you want from me, Jennifer?” I asked.

She looked up at me, and for a moment I saw my little girl again. The one who crawled into my bed during thunderstorms. The one who held my hand at her father’s funeral. The one who once told me I was her hero like it was the simplest truth in the world.

“I want my mom back,” she whispered. “I want to fix this. I don’t know if I can, but I want to try.”

“And Derek?” I asked, because I needed to hear it out loud.

Her face crumpled.

“We’re in counseling,” she said. “Patricia is paying for it.”

That alone told me how serious it was, because Patricia Barrett did not spend money without a reason.

“And she made it clear,” Jennifer added, voice trembling, “that if Derek doesn’t participate seriously, she’s cutting him off. All of it. The house fund. The trust for Lily. Everything. She said she won’t watch him become his father.”

“That’s a start,” I said.

Jennifer nodded like she was clinging to my words like a rope.

“But Jennifer,” I continued, and my voice went steady, “I need you to understand something.”

She looked at me, waiting.

“I stopped that payment,” I said, “not because I was trying to ruin Lily’s birthday.”

Jennifer flinched. I could tell Derek had been feeding her that narrative, painting me as vindictive.

“I stopped it,” I said, “because I couldn’t keep paying people to hurt me. Not even you. Especially not you.”

Tears ran down her face again, but she didn’t interrupt. She just nodded slowly.

“I know,” she whispered. “I know.”

I stared at my daughter, really looked at her.

She’d lost weight. There were lines around her eyes that hadn’t been there a year ago. Beneath the designer clothes and the perfect highlights, I could see how unhappy she was.

I didn’t excuse her choices.

But I understood her fear.

“I don’t know if I can trust you again,” I said. “I don’t know if we can get back what we had.”

Jennifer nodded harder, like she deserved every word.

“I know that too,” she said, wiping her cheeks. “But can we try? Please?”

I let the silence sit between us.

Then I said, “On one condition.”

Her head snapped up, hope flickering.

“You bring Lily here,” I said, “by yourself, once a week. No Derek. No schedule conflicts. No excuses.”

Jennifer’s breath hitched. She nodded quickly.

“She and I spend time together,” I continued. “She knows her grandmother. And you remember where you came from.”

“Yes,” Jennifer said. “Yes. Okay. Anything.”

“And we do family therapy,” I added. “The three of us. You, me, and Lily. To fix what’s broken.”

“Yes,” she whispered again.

I watched her for another beat, then delivered the part she needed to hear most.

“And you pay me back the five thousand.”

Jennifer’s eyes widened. She swallowed.

“Not because I need it,” I said. “But because you need to understand that my money isn’t free. My love isn’t free. It costs respect.”

Jennifer nodded, tears streaming again.

“I’ll pay you back,” she said. “It might take a few months, but I’ll pay you back.”

I stood up, the conversation shifting, like a meeting ending.

“Then we can try,” I said. “But Jennifer… if you or Derek ever make me feel less than again, if you ever exclude me or hide me or treat me like I’m not good enough, I’m done.”

My voice didn’t shake.

“I’m sixty-three years old,” I said. “I don’t have time to spend it with people who don’t value me. Not even my own daughter.”

Jennifer stood too. For a moment we just looked at each other, two women who shared a face and a history and a wound.

Then she stepped forward and hugged me.

I let her.

I didn’t hug back fully. Not really.

But I let her.

That was six months ago.

Jennifer did pay me back. She got a part-time job at a clinic, her first job since Lily was born, and she sent me four hundred dollars a month until the debt was cleared. She brought Lily over every Thursday afternoon, and those Thursdays became my favorite day of the week.

We baked cookies. We went to the park. We did art projects that left my kitchen table stained with paint and my heart stained with something softer than bitterness.

Lily talked about school, about her friends, about the book she was writing. She told me she was writing about a brave grandmother who was also a secret superhero, which made me laugh so hard I had to sit down.

The therapy was harder.

There were sessions where Jennifer cried. Sessions where I cried. Sessions where we both sat in angry silence while the therapist tried to mediate. Slowly, painfully, we started rebuilding something. Not the old relationship. That one was gone. But something new. Something with boundaries, something with truth.

Derek kept his distance.

I’ve seen him exactly three times since the birthday party. Each time he’s been rigidly polite, like a man who’s been warned but still doesn’t believe he should have to change.

Patricia told me the counseling is helping, but it’s slow.

She and I have coffee once a month now. We’re not friends exactly, but we’ve reached an understanding. Two women on opposite sides of a mess, both realizing too late what we helped create.

As for me, I started living differently.

I joined a book club at the public library downtown, the one with the old brick building and the squeaky wooden floors. I took a watercolor painting class at the community center, the kind where everyone laughs at their own mistakes and nobody cares what brand your supplies are. I went on a cruise to Alaska with Susan and Frank, something I never would have done before because Jennifer always needed something, and I always said yes.

I look at my house differently now, too.

It’s not embarrassing. It’s not inadequate. It’s mine.

Bought with my own work, filled with my own memories.

The kitchen cabinets are vintage, not outdated. The garden gnome is whimsical, not tacky.

And if someone doesn’t like it?

They know where the door is.

Last week, Lily asked if she could have her ninth birthday party at my house.

Just family.

“Grandma,” she said, wrapping her small arms around my waist, “you, me, Mom, and Grandpa Derek, if he promises to be nice, and Grandma Patricia. She’s family now too.”

Jennifer looked at me nervously when Lily said it. I could see the question in her eyes.

Will you?

Can you forgive enough for that?

I’m sixty-three years old.

I spent most of my life making myself smaller so other people would be comfortable. I let people treat me like I wasn’t enough because I was afraid of losing them.

But here’s what I learned.

You can’t lose someone who doesn’t value you.

You can only free yourself.

“I think,” I said, looking at my granddaughter’s hopeful face, “that sounds perfect.”

And I meant it.

Not because everything was fixed. Not because the hurt had disappeared.

But because I’d finally learned the most important lesson.

I was enough.

I always had been.

And anyone who couldn’t see that didn’t deserve a place at my table, no matter how much money they had or how expensive their house was.

The party’s next month.

We’re keeping it simple.

Pizza. Cake from the grocery store bakery. Decorations from the dollar store.

Lily’s helping me plan it. She wants a craft station where everyone makes friendship bracelets.

“Make sure there are enough supplies for you too, Grandma,” she said yesterday, squeezing me like she was afraid I’d disappear again. “You’re not just helping with the party. You’re the guest of honor.”

Guest of honor at my own house for my granddaughter’s birthday.

Exactly where I belong.

The thing about saying, “We’re keeping it simple,” is that it sounds easy until you’re the one doing it. I told myself I wasn’t going to overthink Lily’s ninth birthday party at my house, but the moment it became real, I started noticing everything. The scuffed baseboards. The squeaky screen door. The way my living room still smelled faintly like the lemon polish I’d used since the early 2000s. I caught myself walking around like a hostess at a bed-and-breakfast, straightening throw pillows that didn’t need straightening, then stopping and laughing at myself because who was I trying to impress, exactly.

That old reflex was still in me, though. The reflex to prepare, to prove, to earn.

And it wasn’t just the house. It was the idea of being the “center” again, even for something small. For years, I’d gotten used to being the background, the person you call when you need a babysitter, the person you thank quickly before you rush back to the life you’re proud of. I’d gotten used to being grateful for scraps. Now Lily was asking for a party at my house, and she was saying it like it was the most obvious choice in the world, like of course Grandma’s house is where you celebrate, where else would you go.

That kind of love is simple. Adults make it complicated.

The first Thursday after Jennifer and I talked, she brought Lily over alone like she promised. Lily bounced out of the car holding a backpack that looked too big for her body and a little gift bag she’d decorated with stickers. She ran straight into my arms like she’d been saving up all week for that hug.

“Grandma!” she yelled, her voice echoing down my hallway.

I hugged her tight, breathing in that warm, clean kid smell, sunscreen and shampoo and something sweet like she’d eaten a cookie in the car. Jennifer stood behind her in my doorway, hands clasped in front of her like she wasn’t sure where to put herself anymore.

Lily pulled back and looked up at me. “Mom said I can come every Thursday,” she announced, as if she was making an official proclamation.

“Is that right?” I said, smiling.

Jennifer nodded quickly. “Yeah. We’re… we’re sticking to it.”

I didn’t say thank you. I didn’t make it easy for her to feel like she’d just done me a favor. This wasn’t a favor. This was what should have been happening all along.

Lily marched into my kitchen like she owned it, opened my fridge without asking, and said, “Do you have strawberries?”

I laughed. “I might.”

She turned, eyes wide. “Can we make those strawberry shortcake cups? The ones we did last summer?”

The fact that she remembered made my throat tighten. Kids remember everything you think they’ll forget.

“We can,” I said, and I set out bowls and whipped cream and those little sponge cake rounds from the grocery store bakery. Lily climbed onto a chair and took her job very seriously, lining everything up, organizing like a tiny, confident manager.

Jennifer hovered at the edge of the kitchen, watching us like she was afraid the moment would dissolve if she blinked.

At one point Lily reached for my hand and said, “Grandma, you have to wash the strawberries with me because you always do it better.”

Jennifer flinched, just slightly, like the sentence had hit a bruise.

I didn’t look at her right away. I kept rinsing strawberries, my hands under the cold water, and I said, “Well, it’s because I’m old and wise.”

Lily giggled. Jennifer made a sound somewhere between a laugh and a sigh.

When Lily was busy spreading whipped cream with the seriousness of a surgeon, Jennifer finally spoke.

“Mom,” she said softly.

I glanced at her.

“I listened to the voicemails,” she said, voice tight. “From that day.”

I didn’t respond. I kept slicing strawberries, even though my hands had gone a little shaky again.

“Derek… he was awful,” she admitted. “He said things he shouldn’t have said. About you.”

I set the knife down and wiped my hands on a towel, taking my time. I’d learned something in the last few months: if you move too quickly to soothe someone else, you miss the moment they’re finally telling the truth.

“What did he say?” I asked.

Jennifer swallowed. “He kept calling you ‘unstable’ and ‘dramatic.’ He told me to block you for a while and let you ‘cool off.’ He said… he said you’d crawl back like you always do.”

There it was again. That same sentence, wearing a new outfit.

She’ll get over it.

I looked at Jennifer and felt my chest go tight, not with shock this time, but with a quiet, steady anger.

“And what did you say?” I asked.

Jennifer’s eyes filled. “I didn’t say anything,” she whispered. “At first. I just… froze. And then Lily started crying and refusing to do the candles and everything was falling apart and I realized… I realized I’d let him talk about you like you weren’t even a person.”

Lily interrupted from the table. “Grandma, do you want extra strawberries or normal strawberries?”

“Extra,” I said immediately, and Lily nodded like that was the correct answer, because of course it was.

Jennifer gave a shaky laugh, then wiped her cheek fast.

“I’m trying,” she said. “I’m trying to undo what I did.”

“I know,” I said.

It wasn’t forgiveness. It was acknowledgment. There’s a difference.

Jennifer nodded like she understood the difference, and she didn’t ask for more.

That Thursday became the first of many. The rhythm started to settle into my bones. Lily would come in, kick off her sneakers by the door, and tell me about her week like I was the safest place for her thoughts to land. Sometimes she talked about school, sometimes about a friend drama that sounded like a soap opera in miniature, sometimes about how she thought dolphins were probably smarter than people.

We did normal things. Crafts. Baking. Walks to the little park down the street with the tired swings and the cracked sidewalk. We’d stop at the ice cream truck in the summer and Lily would always pick something blue that dyed her tongue like a cartoon.

And every time Lily left, she’d hug me and say, “See you next Thursday,” like it was a promise she expected the universe to keep.

Jennifer stuck to her part too. She brought Lily alone. She didn’t call at the last minute to cancel for a “schedule conflict.” She didn’t send Derek as a substitute.

The second time, she stayed a little longer. The third time, she helped me wash dishes without being asked. The fourth time, she sat at my kitchen table and told me she’d applied for a part-time job at a clinic.

“I don’t even know if I remember how to be a working person,” she said, half-joking, half-scared.

“You remember,” I told her. “You just forgot because you didn’t have to.”

She flinched at the truth, but she didn’t argue.

Family therapy started two weeks after that. The first session felt like walking into a room with exposed wiring. The therapist was kind and calm and had the steady voice of someone who’d heard every kind of pain and didn’t get rattled by any of it. Lily went first, because kids always do. She drew a picture of me and her holding hands under a big sun.

“This is Grandma,” she said, tapping my stick figure. “She’s the sun.”

I almost laughed, but it turned into a swallow. Jennifer stared at the drawing like she was seeing it for the first time, like she’d forgotten Lily had an entire universe of love that didn’t revolve around Derek’s life.

When it was Jennifer’s turn, she cried. She cried in a way that wasn’t pretty. Not cinematic. Just messy and real, like her body had been holding it in and finally couldn’t anymore. She admitted things she’d never said out loud. That she’d felt small around Derek’s family. That she’d been terrified of losing their financial security. That she’d started measuring herself by their standards, and when she did that, she had to put me somewhere “lower” so she could feel like she’d climbed.

I listened, jaw tight. Some of what she said hurt in a way I didn’t know language for. Some of it didn’t surprise me at all, which was its own kind of grief.

When it was my turn, I didn’t cry right away. I talked like a nurse giving report, too factual, too controlled.

Then the therapist asked me one question, gentle and direct.

“Victoria,” she said, “when did you first start feeling like you had to earn a place in your daughter’s life?”

And I burst into tears so suddenly I shocked myself. I covered my mouth with my hand like it would hide the sound, but it didn’t. Jennifer’s eyes went wide, like she’d never seen my pain without my permission before.

Lily slid her little hand onto my knee.

“It’s okay, Grandma,” she whispered.

I don’t know if Lily understood the whole situation. She didn’t need to. She understood enough to know I was hurt, and she understood enough to offer comfort without making it about her. That child has a steadiness in her that makes me both proud and scared, because I know where steadiness comes from.

After therapy, Jennifer would usually look wrung out. She’d sit in her car for a minute before driving away, staring at the steering wheel like it was a complicated problem. Once she said, “I didn’t realize how much I’ve been… disappearing myself.”

I told her, “That’s what happens when you live in someone else’s shadow and call it love.”

She nodded slowly, like she was collecting truths now, building something new with them.

Derek didn’t show up to those sessions. Not the first few.

Jennifer said he was “busy,” but her eyes didn’t look like she believed that explanation anymore. Patricia did show up once, not to participate, but to drive Jennifer and Lily and sit in the waiting room like an anchor. She nodded at me when I walked in, a small, solemn nod that said, I know. I see it. I’m not pretending anymore.

Patricia and I started having coffee once a month. Not at some fancy brunch place, but at a little café near the library that smelled like cinnamon and old books. She’d show up perfectly dressed anyway, because that’s who she is, but she’d sit in a booth and sip her latte and speak like a woman who was finally tired of her own performance.

“I should have stopped him years ago,” she said once, eyes fixed on the foam in her cup.

“You should have,” I agreed.

She looked up at me, startled, then slowly nodded. “Yes,” she said. “I should have.”

There was no point in me softening it for her. She didn’t need comfort. She needed truth.

“I told him,” Patricia added quietly, “that if he doesn’t do counseling seriously, he can figure out his own finances. He thinks I’m bluffing.”

“I don’t think you are,” I said.

Patricia’s mouth tightened, like she was holding back something sharp. “Neither do I.”

The part that surprised me was how much relief I felt knowing Derek wasn’t untouchable. Not because I wanted him ruined. I didn’t. I just wanted him limited. I wanted him to understand he couldn’t rearrange people’s lives like furniture.

Meanwhile, I was living again, in small ways at first. I joined a book club at the public library, the one that meets in a room with folding chairs and a pitcher of water on a table like it’s a community meeting. The first night I went, I almost turned around in the parking lot because I felt silly, like I didn’t belong.

Then Susan texted me, “If you bail I’m coming over and dragging you inside myself,” because she’d decided this was her mission now: get me back into my own life.

So I went. I sat down. I listened to a group of women debate a novel like it mattered, like stories mattered. Someone laughed at something I said. Someone asked me my opinion. And when I drove home, I realized I’d gone an entire two hours without thinking about Jennifer or Derek.

That felt like freedom.

I took a watercolor class at the community center too, and my first painting looked like a sad storm cloud hovering over a blob of grass. The instructor told me, kindly, “You’re being too hard on yourself,” and I laughed because of course I was. Being hard on myself is basically my hobby.

Lily loved my paintings anyway. “This one looks like a dragon,” she said about the sad storm cloud, and from that moment on, it was a dragon, because when you let a child name something, they make it more generous.

The Alaska cruise happened in late summer. Susan planned it like a military operation. She booked it, told me what to pack, and said, “Don’t you dare cancel.” On the ship, I stood out on the deck with a blanket around my shoulders and watched mountains rise out of the water like something out of a movie. I watched whales breach in the distance, small and huge at the same time, and I felt my own life stretch wider than the narrow lane I’d been staying in.

I took pictures. I sent Lily one of a glacier and she replied, “WOWWWWWW” with about fifteen W’s and a bunch of sparkly emojis. She asked if ice is really that blue. She asked if whales have grandparents.

“It’s a whole thing,” Susan said, leaning on the railing beside me. “You’re coming back to yourself.”

I told her, “I’m trying.”

She nudged my shoulder. “You are.”

And then June rolled around, which meant Lily’s birthday party at my house was suddenly two weeks away and I was standing in Dollar Tree staring at a wall of decorations like I was planning a wedding.

It was ridiculous. I knew it was ridiculous. But I still wanted it to feel special.

I bought a banner that said HAPPY BIRTHDAY in glitter letters. I bought pastel plates and napkins. I bought those cheap plastic tablecloths that rip if you look at them wrong. I bought a pack of balloons and a roll of curling ribbon and then a second roll of curling ribbon because I didn’t trust the first one to be enough.

For the craft station, Lily insisted on friendship bracelets. She made me a list in her neat, careful handwriting: embroidery floss, beads, little letter charms, scissors, tape, and “a bowl for scraps because Mom says scraps are messy.”

I took her list to Michaels and felt like I was learning a new language. I stood in the aisle surrounded by rainbow string and sparkly beads and teenagers buying supplies for something I didn’t understand, and I caught myself smiling.

This was normal. This was what grandmas do. This was what I should have been doing all along, without paying five thousand dollars to be tolerated.

Jennifer offered to help set up, which I accepted, but with boundaries. She didn’t bring Derek. She didn’t call it “my mom’s cute little party.” She simply showed up with Lily’s supplies and a couple pizzas she’d ordered in advance, because she was trying, really trying, to relearn what respect looks like in actions, not words.

The day before the party, Jennifer hesitated in my kitchen. Lily was in the living room making a sign that said CRAFT ZONE with crooked letters and glitter glue.

Jennifer cleared her throat. “Mom,” she said, voice cautious, “about Derek…”

I didn’t look up right away. I was lining up plastic cups on a tray, the way you do when your hands need something to do.

“What about him?” I asked.

Jennifer swallowed. “Lily really wants him there,” she admitted. “She keeps saying ‘Grandpa Derek’ and… she wants everyone. She wants it to be like… like how she thinks family should be.”

I stared at the cups, thinking about how children want wholeness even when adults have shattered things.

Jennifer added quickly, “He knows he has to behave. Patricia told him. I told him. Everyone told him.”

“That doesn’t mean he will,” I said.

“I know,” Jennifer whispered. “But… would you consider it? If he agrees to your rules?”

I turned then and looked at my daughter. Her face held that nervous hope again, the one that used to make me cave. The one that used to make me give in to keep the peace.

I didn’t give in automatically.

“What are my rules?” I asked her.

Jennifer blinked. “Respect,” she said softly.

“And?” I pressed.

“And… no comments about your house,” Jennifer said. “No jokes. No… no treating you like you’re less.”

“And?” I said, because I needed her to say it all the way out loud.

Jennifer took a breath. “And if he crosses a line, he leaves,” she said. “Immediately. No arguing.”

I nodded. “Then yes,” I said. “He can come. On probation.”

Jennifer let out a breath like she’d been holding it for days. “Okay,” she said. “Okay. Thank you.”

I held up a hand. “Don’t thank me,” I said. “This is for Lily. Not for him.”

Jennifer nodded quickly. “I know.”

The morning of the party, I woke up early because my body still thinks big days require extra hours. I brewed coffee, opened the windows, and let summer air drift through my house. Outside, my roses were starting to bloom again, soft pink petals against the green, stubborn and beautiful. I stood in my kitchen in slippers and watched sunlight move across the counter and I felt something I hadn’t felt in a long time.

Peace.

Not perfect peace. Not “everything is fixed” peace. But a quiet sense that I belonged in my own life.

By noon, Lily arrived, already wearing a handmade crown from her school’s art room, glittery and slightly crooked.

“Grandma,” she announced the second she walked in, “today is going to be the best day.”

“That’s a big statement,” I said, laughing.

“It’s true,” she insisted, and she marched into my kitchen and asked if she could lick the frosting spatula, because some traditions matter.

Jennifer came in behind her carrying a grocery store cake box. The cake was simple, white frosting, pink trim, and a big “9” candle taped to the top. It wasn’t some custom bakery masterpiece. It was exactly what I wanted: sweet, normal, real.

Susan showed up next, holding a gift bag and a pack of extra napkins like she was on my party committee now. Frank followed with a folding table for the craft station because he’d decided my kitchen table needed backup.

“You didn’t have to,” I told them.

Susan rolled her eyes. “We wanted to,” she said, and there was that phrase again, the phrase that still stunned me when people offered it without me earning it.

Lily’s friends arrived, a handful of kids with ponytails and loud laughter and parents who looked relieved to drop them off somewhere safe. Some of the parents had that Riverside Academy polish, but in my house they stood a little awkwardly, unsure how to behave without their usual script.

And then Patricia arrived.

She stepped out of her car with a bag of balloons like she’d raided a party store, and she actually smiled when she saw my rose bushes.

“These are beautiful,” she said, and her voice sounded real.

“Thank you,” I replied, and for a moment it felt almost normal, two grandmothers standing on a porch while kids ran inside.

Jennifer’s car pulled back into the driveway a few minutes later.

And Derek stepped out.

He paused on my driveway like he was stepping onto foreign soil.

He wore khakis and a button-down, casual but expensive, the kind of casual that still costs money. He held a small gift bag in one hand and wore a smile that looked practiced, like he’d rehearsed it in the mirror.

He walked up the porch steps and said, “Victoria,” in that smooth tone.

I didn’t move out of his way. I didn’t shrink.

“Derek,” I said.

His eyes flicked over my house quickly. Not as obviously as before, but I caught it. The tiny scan, the automatic measurement.

Then he seemed to remember himself. His smile tightened.

“Thank you for having us,” he said.

It was the right sentence. It sounded like it cost him something to say it.

“You’re here for Lily,” I replied, calm.

He nodded quickly. “Of course,” he said, and Lily chose that moment to burst through the doorway yelling, “GRANDPA DEREK!” like she was a tiny hurricane of joy.

Derek’s face softened in spite of himself. He bent down, and Lily threw her arms around his neck.

“I’m glad you came,” Lily told him matter-of-factly. “You have to be nice today.”

Patricia made a sound that was half cough, half laugh.

Derek straightened up, cheeks slightly pink, and he said, “I can do nice,” as if he was making a formal pledge.

Lily pointed at my kitchen. “Grandma is the guest of honor,” she announced, loud enough for everyone to hear. “So nobody can be mean to her.”

A couple parents chuckled awkwardly. Susan muttered, “I love this kid,” under her breath.

Derek glanced at me, and for a moment I saw him recalculating. He didn’t have a script for a child calling him out. He didn’t have a way to make it my fault.

He cleared his throat. “Well,” he said, trying to sound light, “then I’ll be on my best behavior.”

“Good,” I replied, and I smiled, small and steady, because I wasn’t afraid of him anymore.

Inside, the party went the way kids’ parties go. Loud. Messy. Sweet. Lily’s friends ran from the craft station to the backyard and back again like my house was a playground. They made bracelets with too many beads and spelled words wrong and laughed like that was the whole point.

I watched Lily sit at the folding table with her tongue sticking out in concentration as she tied knots, and my chest felt full in a way that hurt, the way love hurts when you almost lose it.

Jennifer floated through the party looking both relieved and fragile. She kept glancing at me like she was checking whether I was still here, still solid. At one point she approached the craft table and asked quietly if I needed anything.

“Just enjoy it,” I told her. “Be present.”

She nodded, eyes shining.

Derek stayed mostly quiet. He laughed at the right times. He handed out pizza slices. He kept his comments to himself. I could tell it took effort, like he was holding a leash on something inside him that wanted to judge, to control, to dominate the room.

Once, when he saw my old kitchen cabinets, I saw a familiar smirk twitch at the corner of his mouth, like the old Derek about to make his little joke.

Patricia’s gaze snapped to him like a warning.

Derek’s mouth closed.

He picked up a stack of plates instead, wordlessly.

Susan caught my eye and raised her eyebrows like, Look at that. Progress. Fear-based progress, maybe, but progress.

When it was time for cake, Lily insisted I sit beside her at the table. Not behind her, not in the corner, not “over there,” but right next to her, shoulder to shoulder. She handed me the lighter like I was a co-host.

“Okay,” she said, serious again, “I have a speech.”

Jennifer’s eyes widened. “Lily ”

“No,” Lily insisted, holding up a hand like a tiny politician. “I have to.”

The room quieted because everyone loves a kid speech. It’s adorable and unpredictable.

Lily stood on her chair, crown askew, and looked around at all of us.

“I just want to say,” she began, “that I love my mom. And I love my grandma.” She pointed at me. “And I love Grandma Patricia.” Patricia blinked like she might cry, which I never thought I’d see. “And I love Grandpa Derek too, even when he makes weird faces.”

A couple people laughed.

Lily continued, voice firm. “But my grandma is the guest of honor because her house is where we feel safe. And also she makes the best cookies. So if anyone is not nice today, they have to leave. That’s the rule.”

Silence, then a wave of laughter and clapping, because it was funny and also because it was too honest to ignore.

Derek nodded slowly as if he’d just been placed under oath by an eight-year-old.

Patricia clapped the hardest.

Jennifer stared at Lily like she was seeing her clearly for the first time, not as an accessory to a perfect life, but as a person with a spine.

Lily sat down, satisfied, and whispered to me, “I told them.”

“You sure did,” I whispered back, and I kissed the side of her head, breathing in that sugary frosting smell and feeling, deep in my bones, that she was right.

This was where we felt safe.

When the party started to wind down, parents came to pick up kids, collecting bracelets and leftover cake in napkins. The house looked like a craft store exploded. There were beads in the carpet. Glitter on my countertops. A sticky handprint on the back door glass.

I didn’t care.

After the last guest left, Lily curled up on my couch with a slice of pizza and said, “This was better than the restaurant.”

Jennifer sat on the edge of the armchair, tired and quiet. Derek stood near the doorway like he didn’t know whether he was allowed to sit.

Patricia, surprisingly, was the one who broke the silence.

“This,” she said, looking around my living room, “is what a family party is supposed to feel like.”

Her voice was calm, but the sentence landed heavy, like a verdict.

Derek’s jaw tightened.

Jennifer looked down at her hands.

I didn’t rub it in. I didn’t need to.

Lily yawned dramatically and leaned her head on my shoulder.

“Grandma,” she murmured, half asleep, “you’re not going away again, right?”

I felt Jennifer’s breath catch across the room.

I wrapped an arm around Lily and said, steady and certain, “No, sweetheart. I’m right here.”

And I meant it in every sense of the words. Not just physically. Not just for this party. I meant I was right here in my own life, in my own home, at my own table, and no one was going to erase me again.

Not with money. Not with manners. Not with a guest list.

Just before they left, Derek cleared his throat.

“Victoria,” he said, stiff.

I looked at him.

He hesitated, then said the closest thing to an apology I think he could manage in that moment.

“I… misjudged,” he said, the word clipped. “This was… nice.”

It wasn’t warm. It wasn’t humble. But it was something. And more importantly, it wasn’t power.

I nodded once. “Good,” I said. “Then remember it.”

He didn’t respond, but he held my gaze a second longer than usual, like he was trying to understand the new shape of the world.

After they drove away, Susan stayed behind to help me clean up. She picked glitter off my kitchen counter and said, “You know what I loved most?”

“What?” I asked, rinsing plates.

“The part where you didn’t flinch,” she said. “Old you would’ve been terrified all day. New you? New you didn’t flinch.”

I leaned against the sink and let myself breathe.

“I don’t think I can go back,” I admitted.

Susan smirked. “Good,” she said. “Because going back is how you end up on a guest list you don’t belong on.”

That night, after the house was quiet and Lily’s laughter had faded into memory, I sat at my kitchen table with a cup of Earl Grey and looked around at the mess that was slowly becoming clean again.

My cabinets were still old. My driveway crack was still there. My phone was still not the newest model.

And I felt richer than I had in years.

Because I wasn’t begging for a place anymore.

I was setting the table.

And anyone who couldn’t see my worth, anyone who needed me smaller to feel bigger, didn’t deserve a seat.

Not in my home.

Not in my life.

Not at my table.

The next day after Lily’s party at my house, I woke up with glitter in my hair and a bead stuck to the bottom of my sock.

That sounds funny, and it was, but it also hit me right in the chest, because it was proof. Proof that my house had been loud and messy and full of kids again. Proof that Lily had laughed in my living room, that she’d smeared frosting on my kitchen counter and nobody had died from the lack of marble countertops or designer cabinets.

I stood in my kitchen making coffee, looking at the crooked HAPPY BIRTHDAY banner still hanging across the doorway, and I felt something I didn’t know how to name at first. It wasn’t triumph. It wasn’t revenge. It was a kind of quiet pride that felt almost unfamiliar, like a muscle I hadn’t used in years.

I didn’t have to beg for that day.

I didn’t have to pay to be tolerated.

I didn’t have to swallow my feelings to keep the peace.

And the strangest part was realizing that once you stop doing those things, some people panic. Because they were comfortable with you being small. They were comfortable with you absorbing the discomfort so nobody else had to.

Derek called that afternoon.

Not Jennifer. Derek.

His name came up on my phone, and for a moment my body tried to do the old thing, that automatic tightening in the shoulders, the reflex to brace. Then I remembered Lily on her chair, crown crooked, declaring rules like a tiny judge, and I felt myself straighten instead of shrink.

I let it go to voicemail.

Two minutes later, it rang again.

I let it go again.

Then I sat down at my kitchen table, took a sip of coffee, and listened to the message.

His voice was smooth, controlled, but there was something underneath it, a tightness he couldn’t hide.

“Victoria,” he said. “We need to talk. Jennifer is… upset. Lily is confused. And frankly, Patricia is overstepping. This situation has gotten out of hand.”

Out of hand.

That was rich, coming from the man who tried to erase me with a guest list.

He continued.

“I don’t know what you think you’re doing, but you can’t keep creating drama. It’s unhealthy for Lily. We need consistency. We need adults who can manage their emotions and prioritize the child.”

Then, as if he were doing me a favor, he added, “Call me back.”

I stared at my phone for a long moment. In the past, I would’ve called back immediately just to prove I wasn’t the problem he was implying I was. I would’ve rushed to smooth it over. I would’ve gone into explanation mode, apology mode, peacekeeper mode.

Instead, I made myself a second cup of coffee and watered my rose bushes.

It’s funny how much power you gain when you stop responding on someone else’s timeline.

Jennifer came by later that evening, alone.

She didn’t knock right away. I saw her through the window, standing on my porch like she was gathering courage. She looked tired in that deep way, the kind of tired that isn’t about sleep. It’s about carrying a life that doesn’t fit.

When I opened the door, she looked up at me with that same fragile expression she’d had the day she apologized, like she still didn’t fully trust that I wasn’t going to disappear on her.

“Hey,” she said softly.

“Hey,” I replied.

She stepped inside, and her gaze flicked around the house automatically, like she was seeing it again through someone else’s eyes. Then she stopped herself, took a breath, and looked at me instead.

“Derek called you,” she said.

“I know,” I told her. “He left a voicemail.”

Jennifer winced. “He’s… not happy.”

“Neither was I,” I said, and I kept my voice calm, because this wasn’t about winning. This was about reality.

Jennifer nodded slowly, like she was trying to stay grounded.

“He said you embarrassed him,” she admitted, and the words came out with a little bitterness now, like she was starting to hear how ridiculous he sounded. “He said the party at your house made him look… ‘small.’”

I almost laughed, but it wasn’t funny enough.

“He made himself look small,” I said. “All I did was host my granddaughter’s birthday party.”

Jennifer sat down on the couch and pressed her palms against her knees like she needed something solid beneath her hands.

“I told him,” she said quietly, “that if he feels small in your house, that’s his problem.”

My eyebrows lifted before I could stop them.

Jennifer looked up. “I did,” she repeated, a little stronger this time. “I said, ‘Victoria isn’t the one who made you look bad. You did that when you tried to cut her out.’”

I studied my daughter’s face, and for a moment I saw something that made my chest ache in a different way. It wasn’t just remorse. It was a flicker of backbone. It was her remembering herself.

“Good,” I said.

Jennifer swallowed. “He got angry,” she admitted. “Not yelling-angry in front of Lily, but… that cold angry. He told me Patricia is manipulating me. He told me you’re manipulating me.”

“Of course he did,” I said. “That’s what men like that do. If they can’t control the narrative, they accuse someone else of controlling it.”

Jennifer nodded, eyes glassy.

“I told him we’re doing therapy,” she said. “And that he needs to show up.”

I didn’t interrupt. I let her say it.

“And then,” Jennifer continued, voice shaking slightly, “he said he doesn’t need therapy. He said I’m the one who’s ‘overreacting’ because I’m ‘too emotional.’”

There it was again. That old trick. If a woman has feelings, she’s unstable. If a woman has boundaries, she’s dramatic. If a woman refuses to be erased, she’s creating problems.

“I told him,” Jennifer said, and her voice got stronger, “that he can either come to therapy and learn how to be part of this family, or he can watch from the outside while Lily and I build one without his attitude.”

I blinked.

Not because I didn’t believe her. Because I’d waited years to hear her say something like that. Years.

Jennifer’s eyes filled and she looked down quickly, embarrassed by her own tears.

“I don’t know who I am right now,” she whispered. “It feels like I woke up and realized I’ve been living someone else’s life.”

I sat down across from her.

“That’s scary,” I said. “But it’s also a chance.”

Jennifer nodded, wiping her face. “I feel guilty,” she admitted. “Not just for what I did to you. For what I taught Lily without realizing it.”

I thought about Lily’s speech, her little voice insisting on kindness like it was a law of nature.

“Kids learn fast,” I said. “But they also forgive fast when they feel safe.”