The American soldier wasn’t being cruel.

He wasn’t mocking her.

He was genuinely confused.

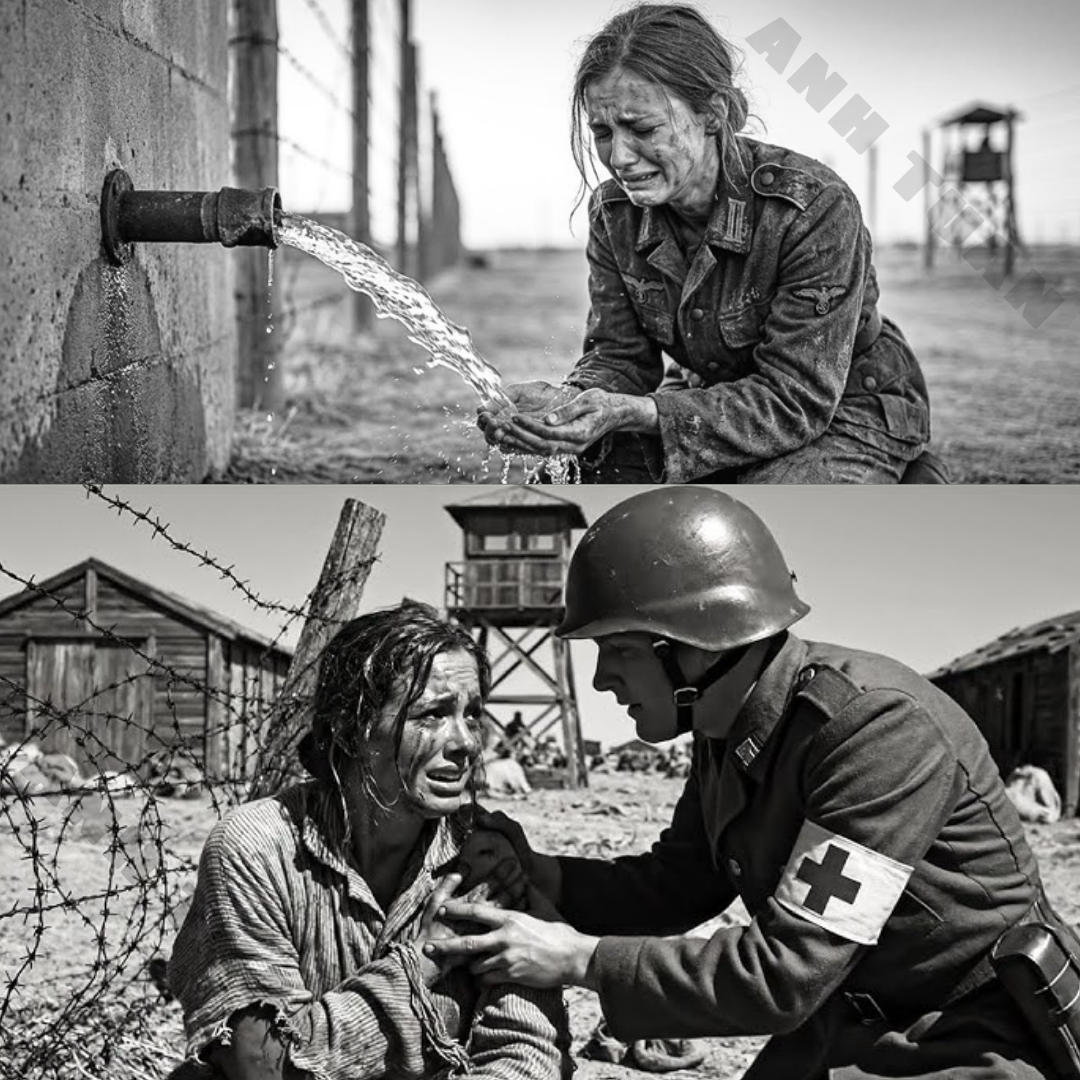

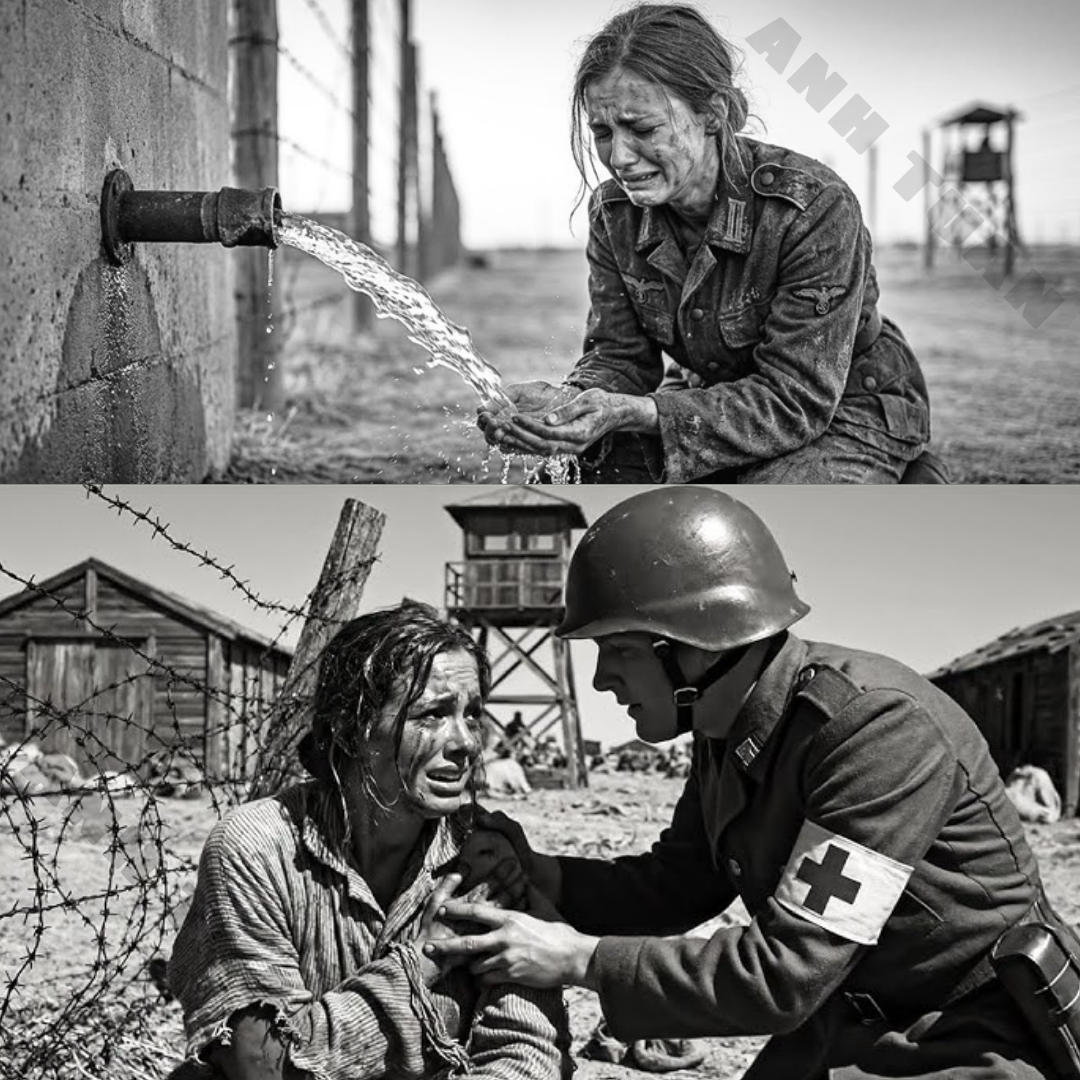

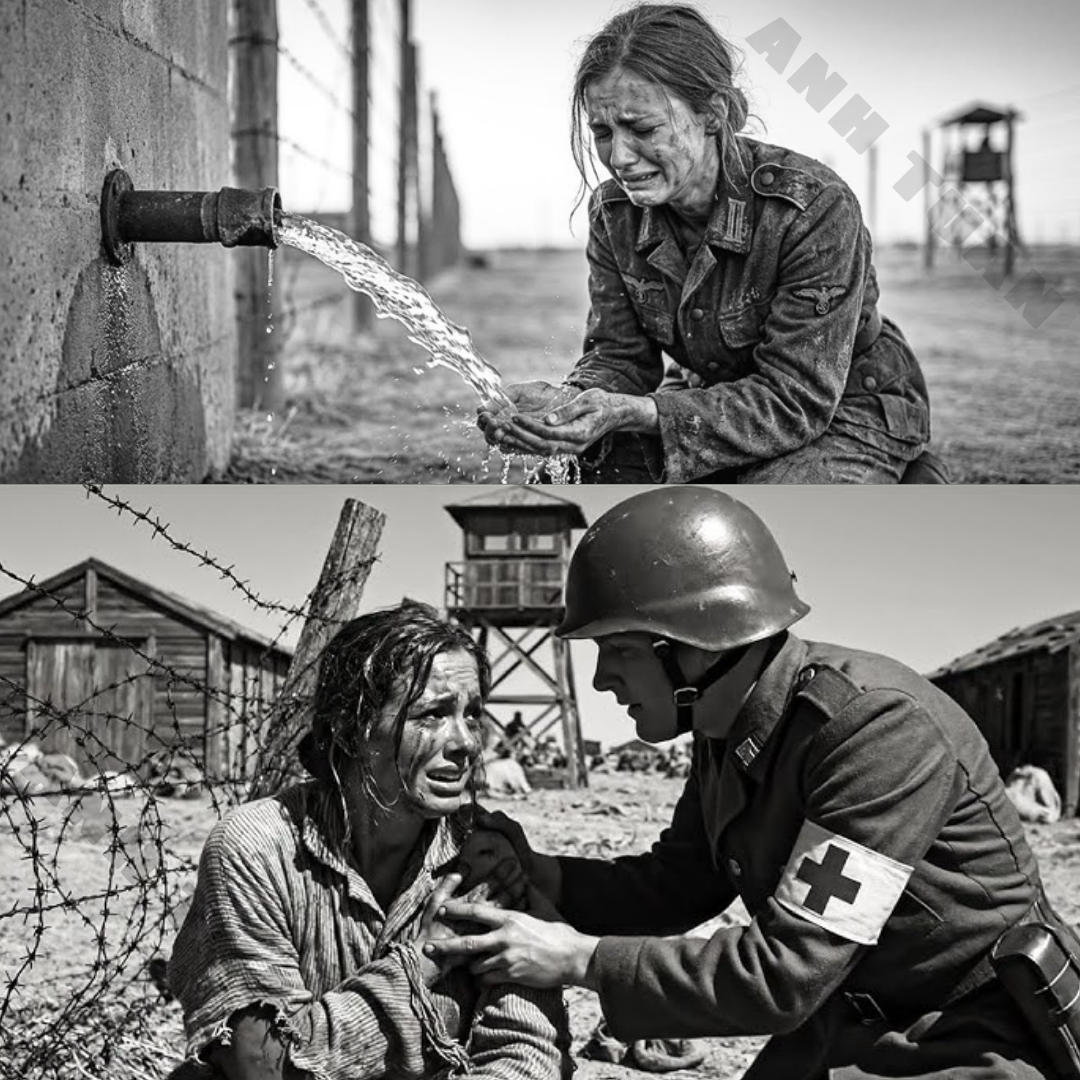

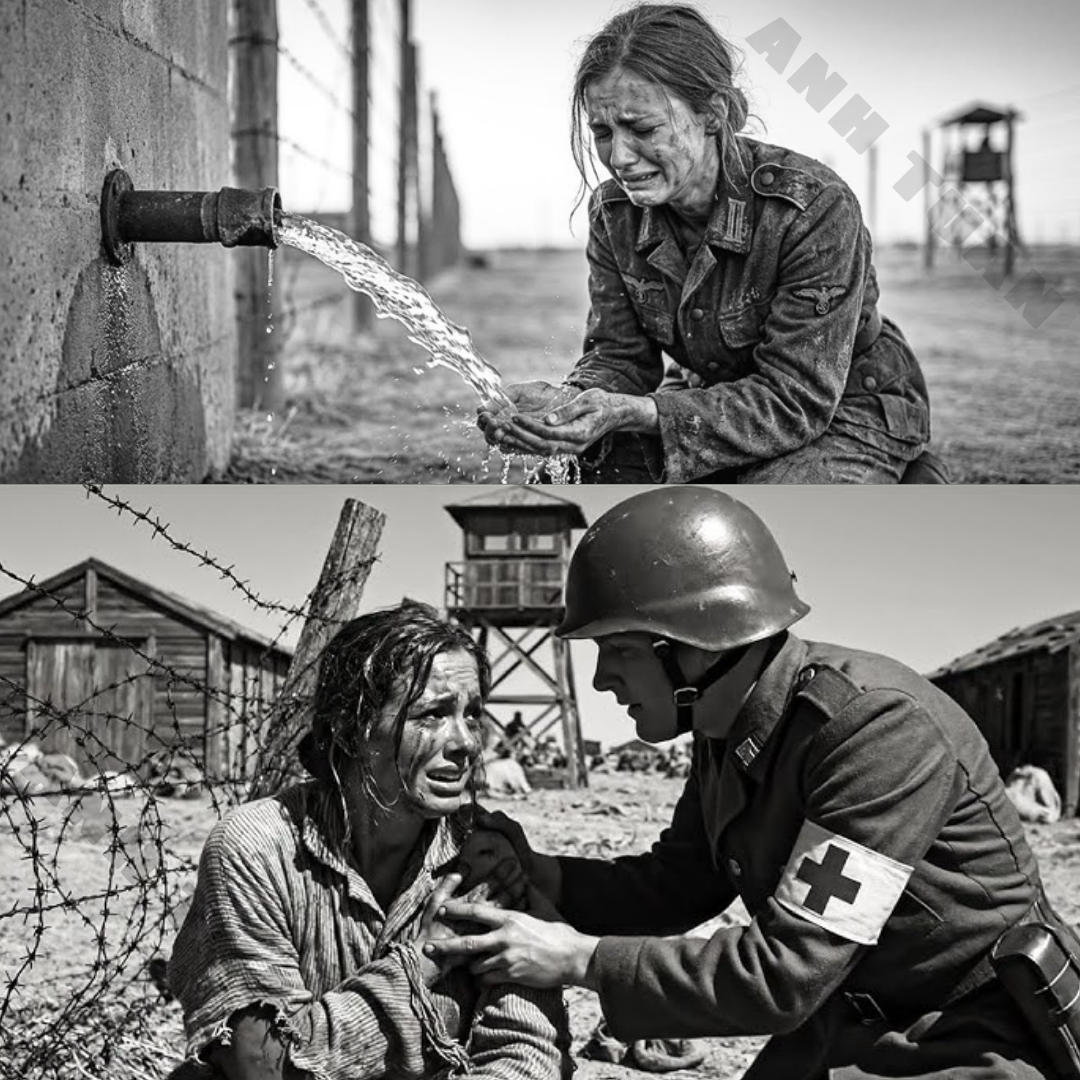

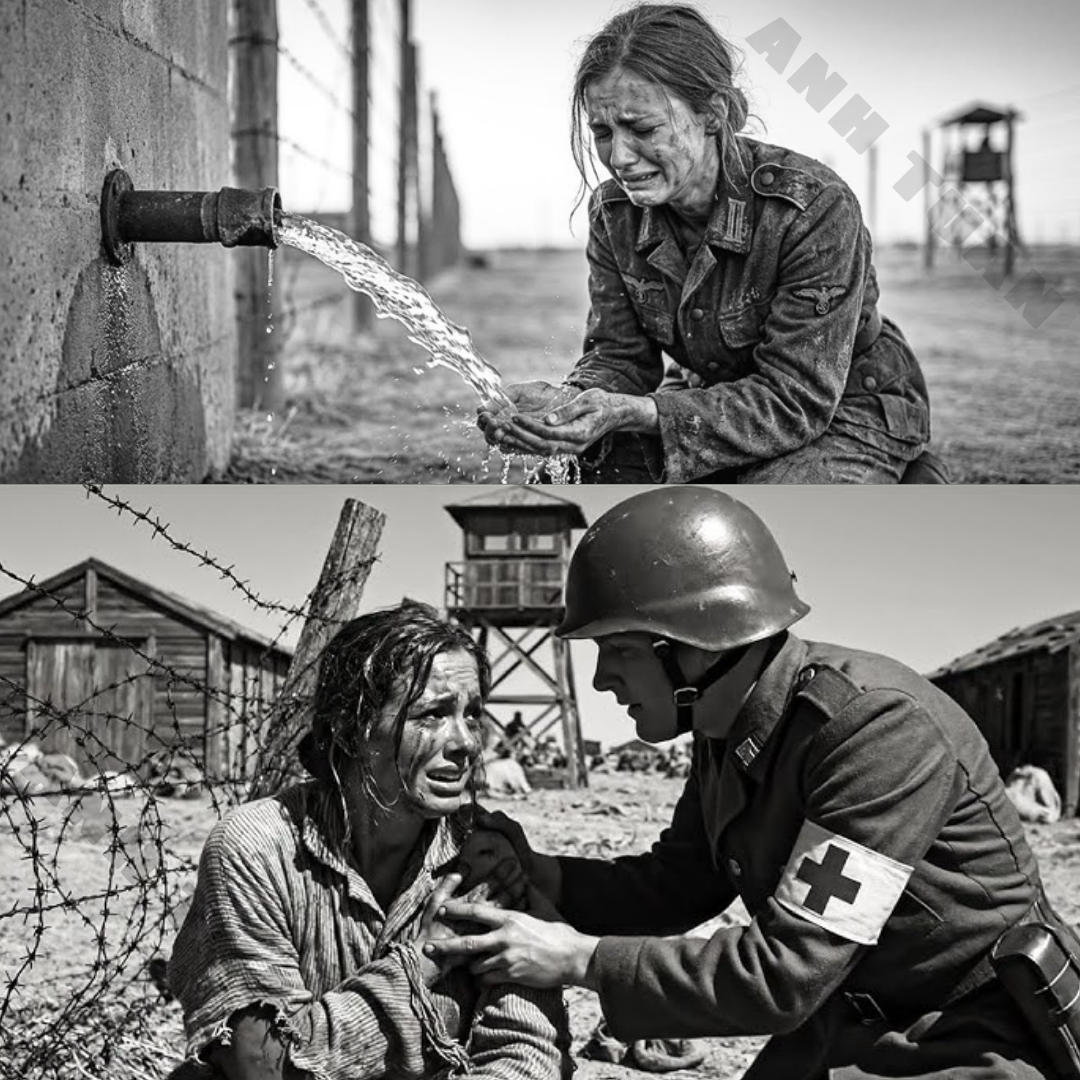

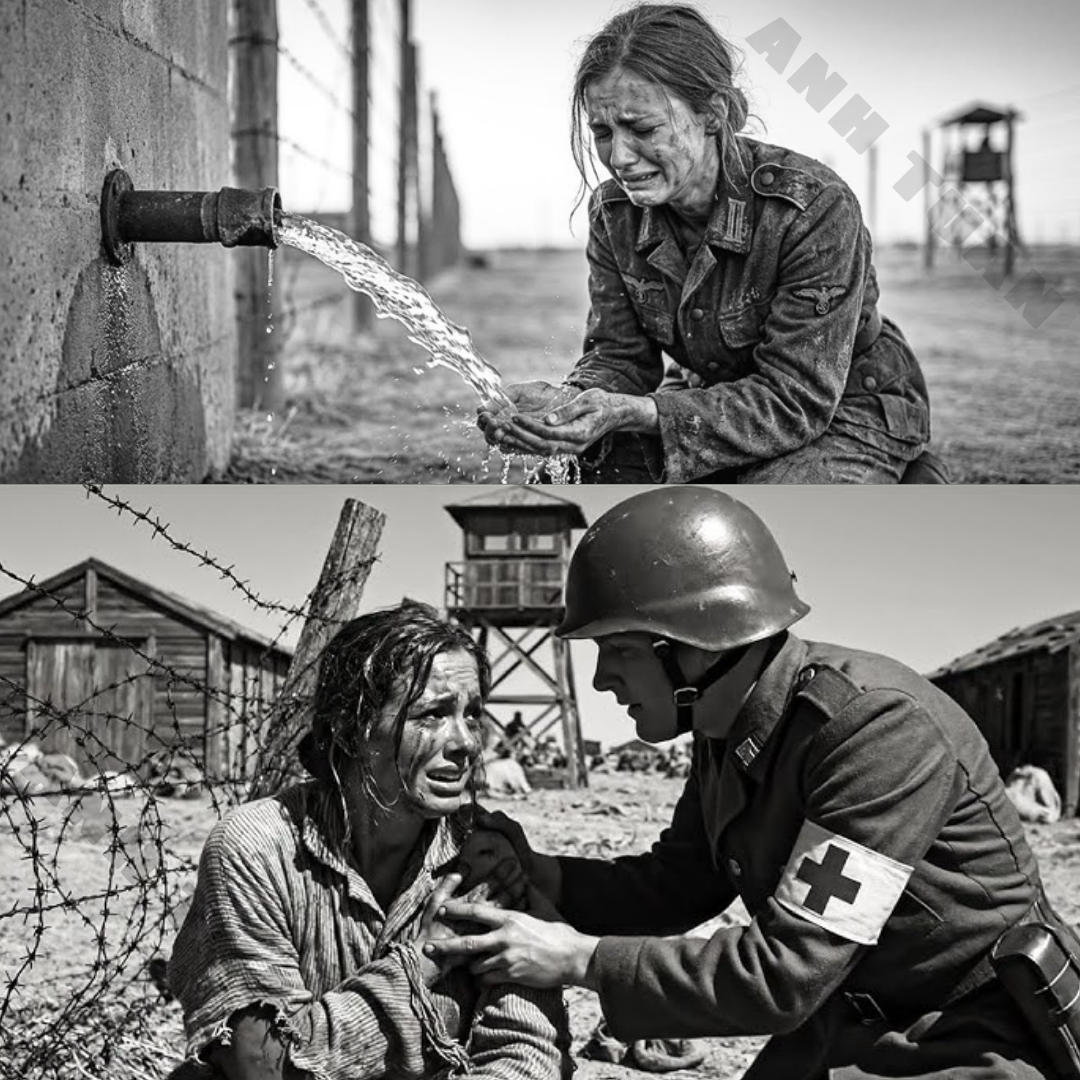

The woman took the canteen with hands that shook so hard the metal trembled against her fingers. She lifted it the way you lift something you want but don’t trust, brought it to her mouth, swallowed once just once and then her knees buckled as if the ground had decided she no longer needed to stand. Tears poured down her face with no warning, not the tidy kind you can blink away, but the kind that come from a place inside you that has been locked for too long.

“Why are you crying?” he asked softly.

To him, it was water.

To her, it was the first time in years her body had believed she might be safe enough to swallow without bracing for pain.

The morning had the kind of cold that didn’t sparkle. It sank. It smelled like wet straw, diesel exhaust, and smoke that had been in the air so long it felt baked into the sky. The camp sat on tired ground outside a small Bavarian town where the road signs were chewed with bullet holes and patched with splintered boards. Beyond the fence line, leafless trees stood like thin bones, and the snow that remained wasn’t white anymore. It was gray at the edges, pressed down by boots and time.

A U.S. Army truck idled near the gate, its engine muttering, the exhaust curling into the air like a slow breath. A big American flag hung from the side, dulled by grime, still unmistakable. It moved only when the wind remembered to exist.

The soldier had been awake since before dawn, moving with the careful efficiency of someone who had learned not to waste motion. He was young enough that, without the helmet and the fatigue carved into his face, he might have passed for a high school senior back home. The war had made him older anyway. Shadows lived under his eyes. The corners of his mouth were tight even when he tried to soften them.

He had handed out canteens all morning. Some people drank fast, wiped their mouths with the backs of their hands, and stared at the truck like it might vanish. Some took the canteen, hesitated, then drank as if expecting punishment to follow. One old man kissed the cap before he swallowed, murmuring a prayer in a language the soldier didn’t know. No one collapsed.

Until her.

She wasn’t tall, or maybe hunger had made her smaller than she should have been. Her coat hung off her shoulders like it belonged to someone else. Her hair was pinned back with a piece of wire, not out of vanity but out of habit, the last scrap of order she could still enforce. Her cheeks were hollow, but her eyes were sharp, the way eyes get when they’ve spent too long watching for the moment a thing changes.

She looked at the canteen the way people look at a lit candle in a blackout wanting it and not trusting it.

When the water touched her tongue, her whole face shifted. Not with joy, not even with relief at first, but with shock that turned immediately physical. Her throat tightened. Her chest seized as if her body had taken one sip and then remembered every other sip that had burned, every swallow that had been a gamble.

The tears came, and then she was on the ground, one hand clutching the canteen as if it could be stolen, the other pressed to her chest like she was trying to hold herself together from the outside. She made a small sound half sob, half gasp that embarrassed her the moment it escaped. Shame rose by reflex. Shame was safer than attention. Shame had protected her more than kindness ever had.

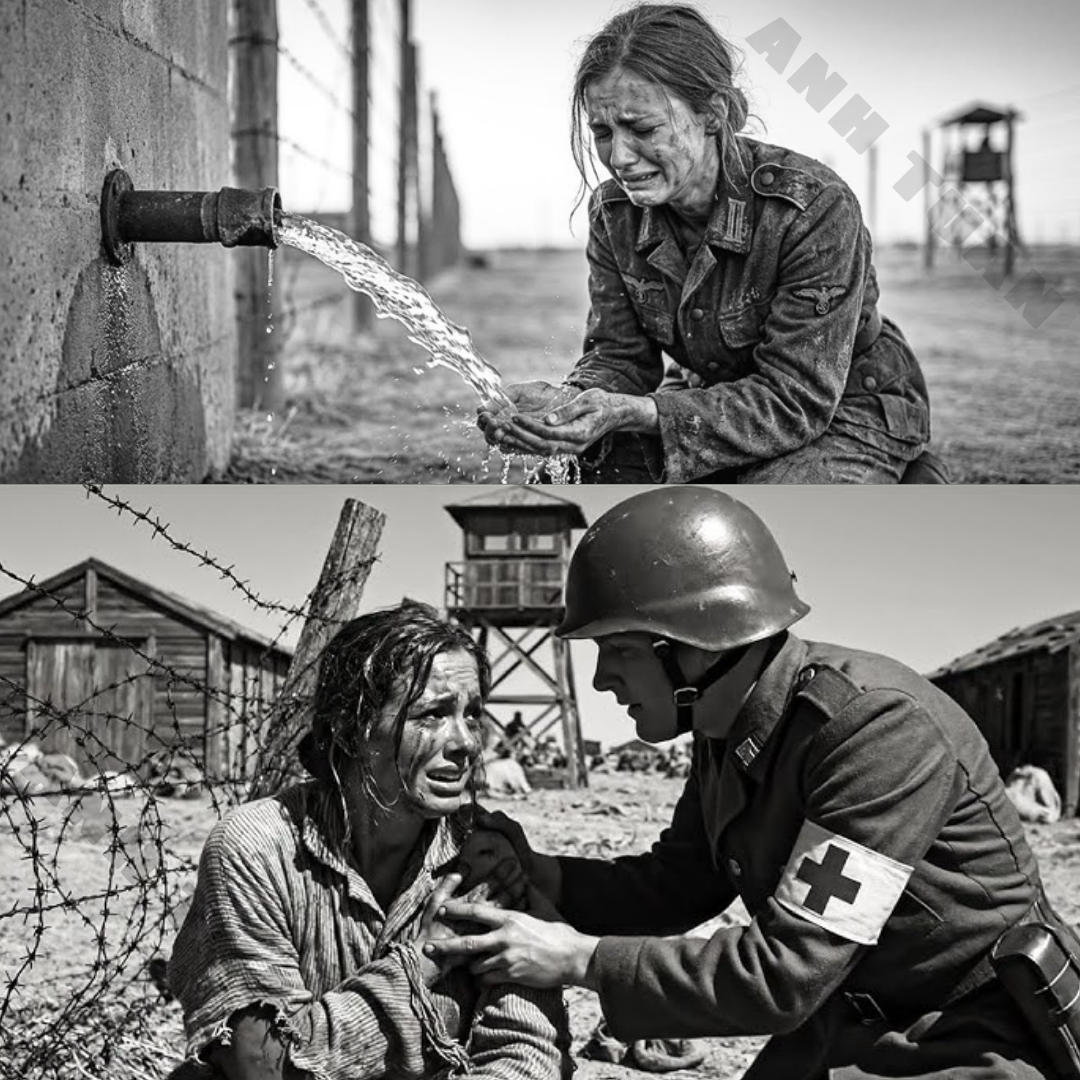

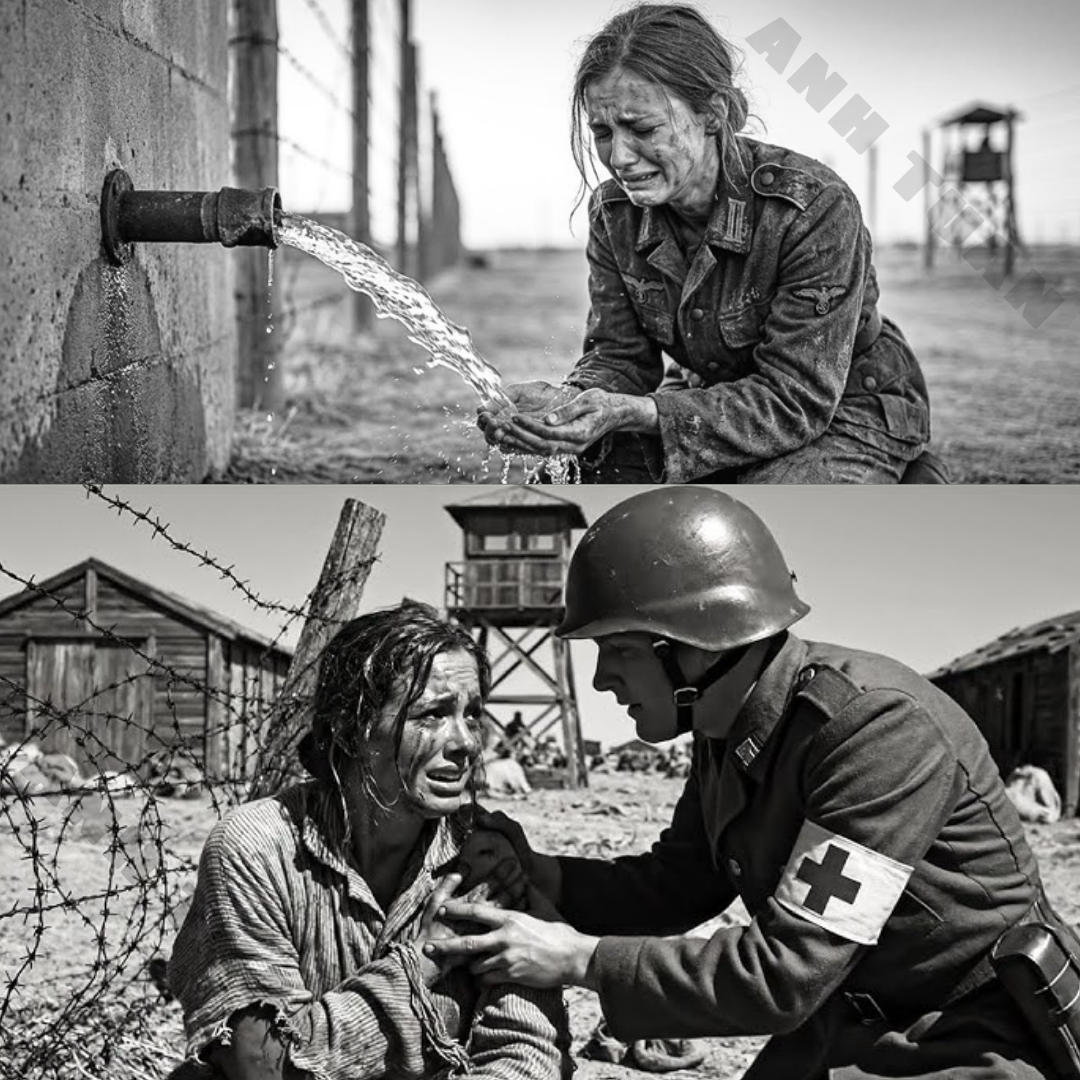

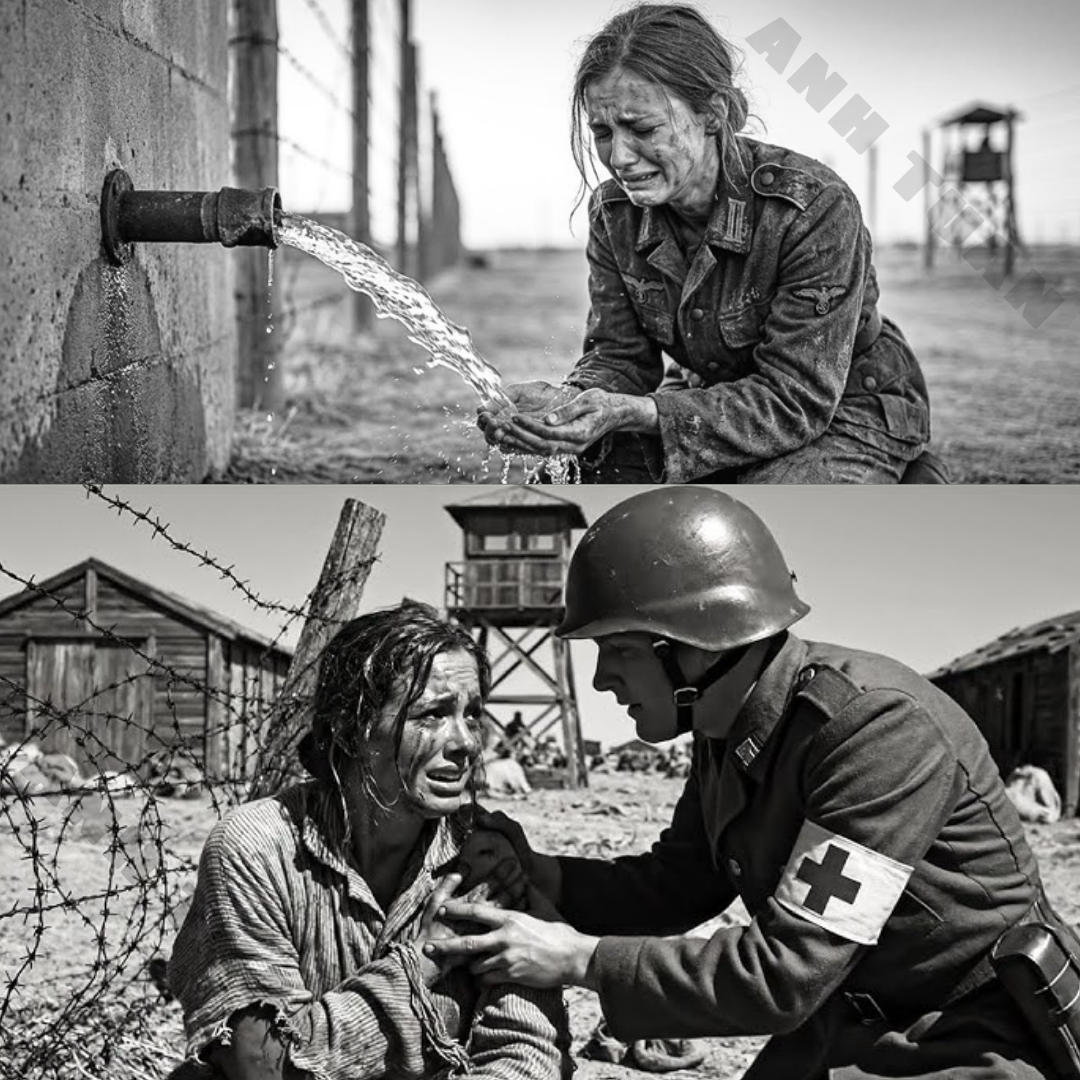

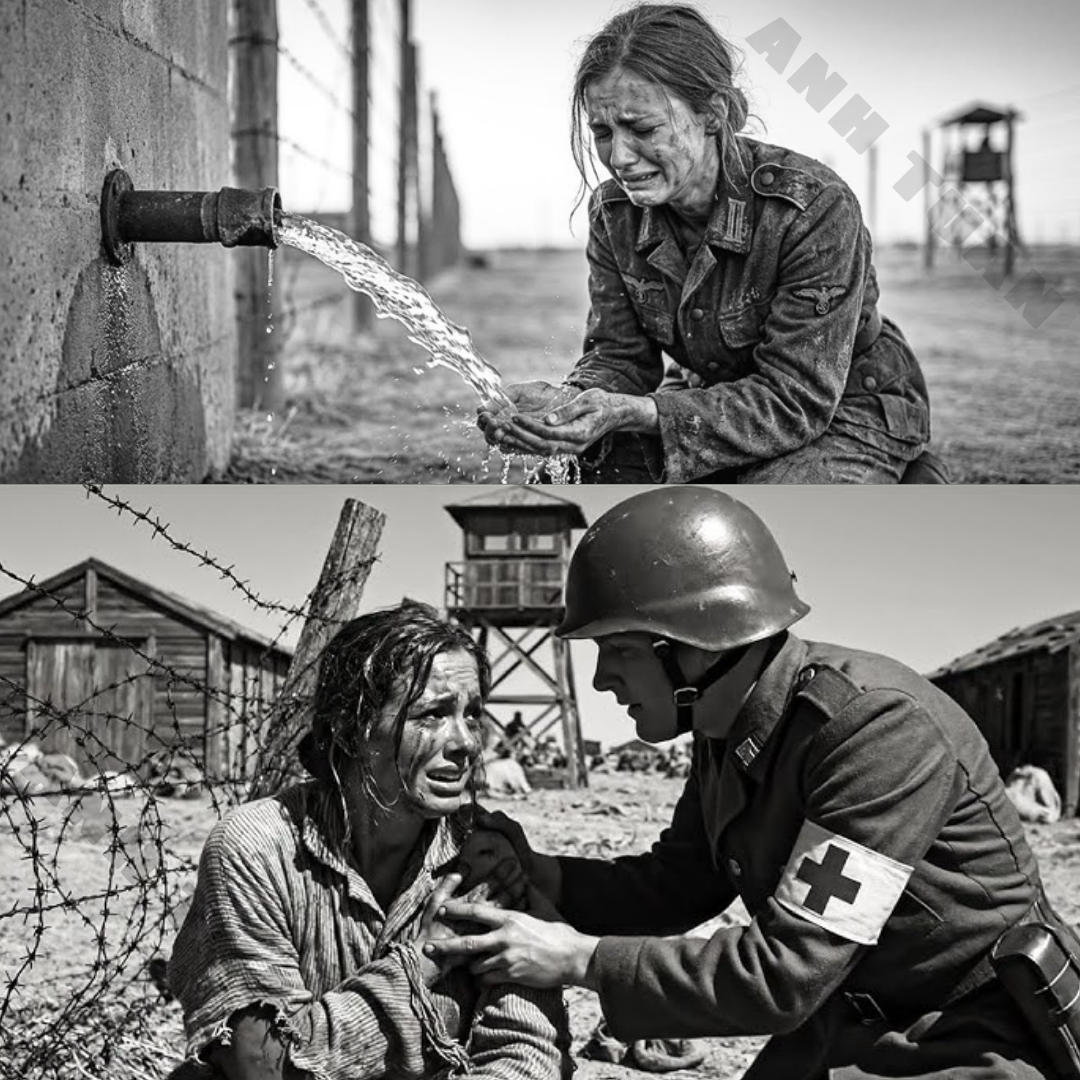

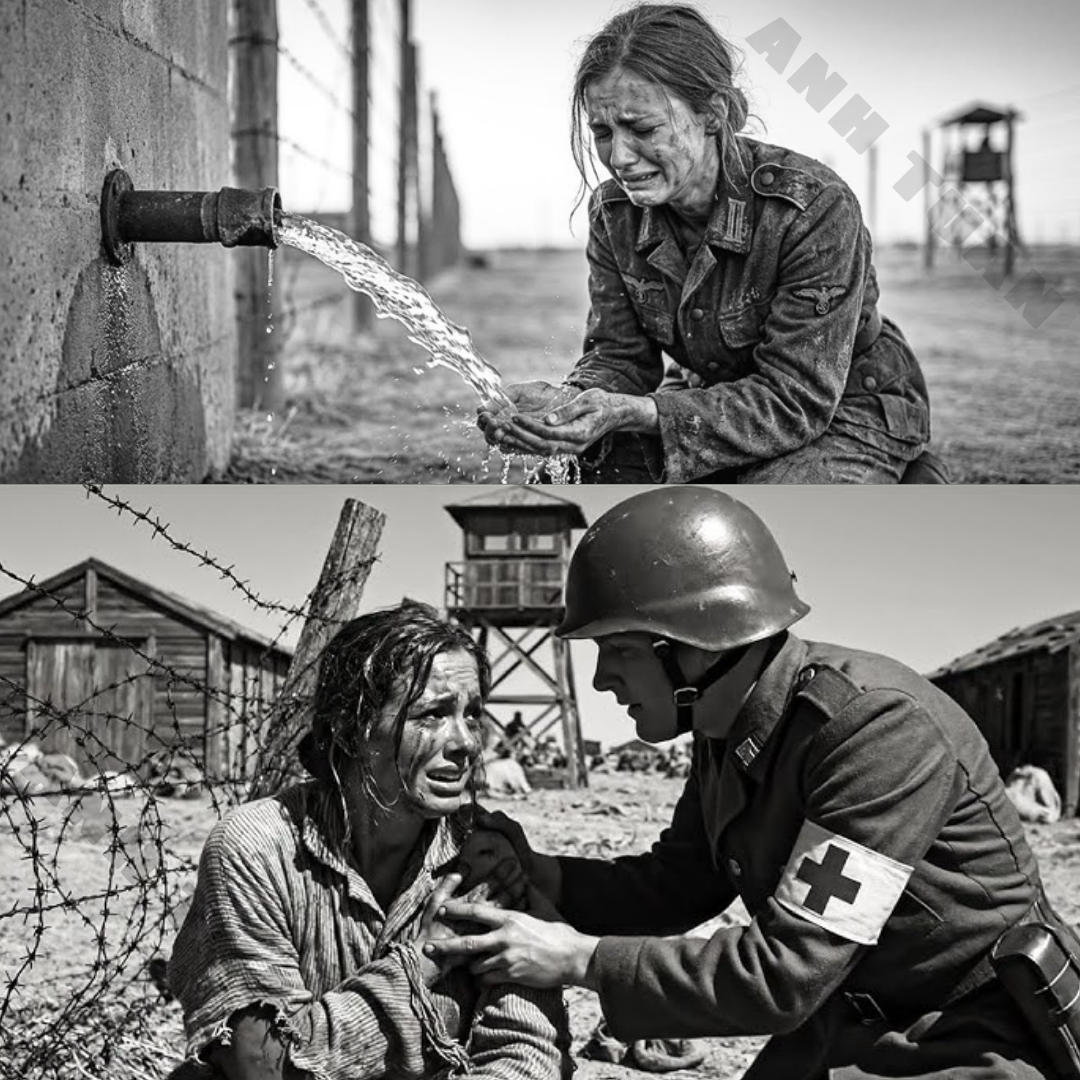

The soldier crouched, boots sinking into mud and packed snow. He kept his hands open, empty, visible.

“Ma’am,” he said, then stopped because he didn’t know what to call her. He didn’t know her name. He didn’t know her story. He only knew the way her body shook like it was trying to shed something it had carried too long.

“You’re safe,” he said, voice gentle but not rehearsed. “It’s okay. Why are you crying?”

She tried to answer him, but to answer him she would have had to start years ago, before the fences and the lists and the classification stamps. She would have had to start with the first thing the war took from her, not loudly, not dramatically, but slowly enough that the loss blended into the background.

Clean water.

It didn’t disappear all at once. It slipped away like daylight in winter, a little less each day until you couldn’t remember when you last felt warm.

Before the war, she had known water as something ordinary and honest. Water was the sound of her mother rinsing dishes in a sink. Water was the soft splash of laundry in a wash basin. Water was the damp smell of a riverbank in summer. It was the way a cold glass sweated on a windowsill, leaving a ring on the wood that her mother pretended not to mind.

She had grown up near Leipzig, in a neighborhood where the buildings were close together and the streets were lined with chestnut trees. In the summers, boys chased each other through sprinklers in the courtyards, shrieking like the world could never end. On Sundays, her father when he was home and not working would take her to the river and point out the way the current moved around rocks, the way it carried small leaves like boats. He wasn’t a sentimental man, but he had a quiet patience for explaining the world.

“Water finds its way,” he would say, as if it was something you could learn from.

As a child, she believed the world was made of steady things. She believed taps would always run clear. She believed the city would always be there, bricks and tram lines and church bells. She believed a glass of water could never be a miracle because miracles belonged to churches, not kitchens.

Then the war arrived the way storms arrive in the distance first newsprint, speeches, uniforms, flags in windows. At first it was a change in the air, a tightening, a sense that adults were suddenly speaking around things. Then it was ration cards and lines and the quiet shift in what people called normal.

Water didn’t become dangerous overnight. It became uncertain.

The first time she noticed was during a summer when the heat made everything smell stronger. The tap in their kitchen sputtered. The water that came out was cloudy for a moment, then cleared. Her mother stared at it longer than necessary, brows pulled tight, as if she could will it back to what it was supposed to be. She ran the water for a while, then filled a pot and boiled it, not because she knew it was unsafe but because caution had become a language.

“Better,” her mother said, as if boiling could restore trust.

Later, when the bombing raids cracked pipes beneath streets and shook the city like a furious hand, the water began to taste faintly metallic. People shrugged and said it would pass. People always said it would pass. Then the water started coming only at certain hours, and neighbors began filling buckets as soon as they heard the pipes wake up. Then the pipes went quiet for days at a time, and the city learned to live around the absence like it was another piece of furniture.

She learned to carry containers.

She learned to listen for rumors about which pumps still worked.

She learned to boil everything.

Then she learned that boiling didn’t fix everything, not when the source itself was wrong.

By the time the war reached its final, collapsing seasons, water was never refreshing. Water was a calculation. Water was a risk.

She drank rain collected in broken containers. She drank melted snow in tin cups that numbed her fingers. She drank liquid drawn from damaged pipes that sometimes smelled of rust or oil or something worse she refused to name. She learned to sip cautiously, to stop before nausea arrived, to accept the ache in her stomach as permanent, like a second heartbeat.

Thirst became constant but manageable, a background hum she couldn’t turn off.

What she did not know was that her body was slowly forgetting something essential. It was forgetting what water was supposed to feel like. It was forgetting that water could be trusted.

Her life, as the war tightened, became smaller and narrower. She had not joined the military. She had not carried a weapon. She had not marched in ideology the way some people did, loud and hungry for belonging. She had been a civilian clerk, a translator’s assistant, someone who typed what she was told to type and filed what she was told to file. She kept her head down because keeping your head down was how you survived when the world went strange.

Her work tied her loosely dangerously to the machinery of a collapsing state. In a sane world, “loosely” would have mattered. In a collapsing one, categories replaced nuance.

German. Female. Associated.

That was enough.

When borders shifted and records failed and armies pressed forward, there were people who needed to be placed somewhere until someone decided what they were. She became one of those people. Detained, moved, relocated sometimes it was called processing, sometimes protective custody, sometimes nothing at all. Just fences and guards and a list of names.

She ended up in a holding camp in the south, far from the city she had known, far from any version of herself that felt recognizable. The camp had been repurposed more than once as the war’s lines shifted. Its paperwork changed hands, stamps layered over stamps until the truth beneath them was almost unreadable. She was classified quickly, because classification was what bureaucracy did when it could not afford to be curious.

Prisoner.

Not because of what she had done, but because there was nowhere else to place her.

Life in captivity was not constant violence. Sometimes it was something worse. It was deprivation without explanation.

Food arrived irregularly. Hygiene supplies were minimal. Medical care depended on availability, not need. And water water was whatever could be found. Guards brought buckets from a pump that ran when it wanted to. Sometimes the water was cloudy. Sometimes it tasted like metal. Sometimes it tasted like nothing at all, which was its own kind of relief.

She stopped expecting clarity. She stopped expecting kindness. She stopped expecting relief. When you stop expecting, disappointment can’t strike as sharply, and that emotional thrift becomes its own survival skill.

Humans normalize suffering remarkably quickly. That is one of our strengths and one of our tragedies. When something bad lasts long enough, it becomes background noise. She forgot what water was supposed to taste like. She forgot it could refresh instead of burn. Her body survived. Her expectations shrank.

Then the day came when the war finally reached the camp, not with fireworks, not with speeches, but with confusion.

American troops arrived under a ceiling of gray clouds. Orders were shouted in English. Gates opened cautiously. Guards stepped back, unsure whether to resist or retreat. Some disappeared as if they had never existed. Others stood still, waiting for someone else to decide what their job was now.

The prisoners women like her did not cheer. Years of uncertainty had trained them not to trust sudden change. They watched from inside the fence line, holding their bodies small, eyes sharp, waiting for the shape of the new rules.

The American soldier assigned to her group noticed something immediately. Not panic. Not aggression. Something quieter. The women moved carefully, too carefully, as if the ground itself might vanish if they stepped too fast. Their eyes tracked hands, because their nervous systems had learned hands were where decisions happened.

A hand could offer bread, or take it away.

A hand could open a gate, or close it.

When he offered a canteen, she hesitated. Not because she was afraid of him, but because she was afraid of the water. Her body had learned that swallowing could hurt, that relief could be dangerous, that the simplest things could come with consequences.

“It’s clean,” he said gently.

She nodded because nodding was easier than arguing, but she didn’t fully believe him. Still, she took it. The canteen was heavier than it should have been, or maybe her hands were weaker than she wanted to admit. The metal was cold against her skin.

She lifted it, swallowed once, and realized impossibly that it didn’t hurt.

That was what broke her.

Not the cold.

Not the taste.

The absence of pain.

Her body reacted before her mind could catch up. Her throat clenched. Her chest seized. Tears surged without warning. The water slid down smoothly no bitterness, no sting, no aftertaste of rust. Her nervous system, conditioned for harm, did not know what to do with safety when it arrived so suddenly.

The soldier’s confusion was genuine. He had given water to dozens of people that day. Some were grateful. Some nodded silently. Some drank quickly as if afraid someone would change their mind. None had collapsed.

He crouched down, concerned, his voice low.

“Why are you crying?”

She tried to answer, and at first no words came. Her mouth trembled. Her mind reached for explanations and found none that fit inside a sentence. The truth was too large, too layered. It contained years. It contained thirst and fear and sickness and the constant bargaining between a body and the world.

She pressed a hand to her chest, still shaking.

“Because,” she finally said in broken English, “it doesn’t hurt.”

The soldier frowned, startled by the simplicity of it.

“Water isn’t supposed to hurt,” he replied.

She looked at him then really looked at him and saw something in his face that made her feel unexpectedly tired. He had been through war, yes, but he had not been through this kind of war. He had not lived the slow recalibration that teaches a body to distrust what should be basic. He had not watched normal disappear in increments so small you only notice when you try to drink.

She wanted to explain. She wanted to tell him that water had been a gamble. That drinking often meant sickness. That thirst never truly left. That relief had been rationed like everything else. She wanted to tell him that this simple sip had reminded her the world could still be gentle.

But the words didn’t exist yet.

All she could do was cry.

He stayed crouched, hands open, unsure what else to do. He glanced back toward the medic truck, then back at her, as if debating whether a medic could treat tears.

“You’re okay,” he said softly. “You’re okay.”

The sentence didn’t fix anything, but it landed in her like a small weight that was somehow comforting. She breathed in through her nose, slow, and felt the cold air sting. She breathed out and watched the steam leave her mouth, proof that she was still here.

The soldier’s name, she would learn later, was Daniel Mercer. He was from Ohio, from a town called Marietta where two rivers met and people liked to talk about the water as if it had personality. He did not tell her all that in the mud beside the fence line. He only told her his name when the day had softened into late afternoon and the camp had become a place of movement instead of stillness.

For now, he helped her stand.

He did it carefully, not grabbing, not yanking, but offering his arm like a handrail. She accepted because refusing would have required energy she didn’t have. Her legs trembled, but she was upright again. The canteen was still in her hand. Her fingers ached from gripping it too hard.

“Easy,” he said, and his voice held something that surprised her. Not authority. Not command. Something close to patience.

A medic came eventually, a man with tired eyes and a cigarette tucked behind his ear. He looked at her the way doctors learn to look, quickly and without panic, assessing rather than judging.

“She fainted?” the medic asked Daniel.

“Sort of,” Daniel said, and then, because he couldn’t quite explain, he added, “She cried.”

The medic’s gaze flicked to the canteen, then back to her face. He did not smile, but something in his expression softened.

“Yeah,” he said quietly, as if to himself. “That tracks.”

He checked her pulse, asked a few questions she struggled to answer, then nodded.

“She’s not sick,” he told Daniel, not loudly. “She’s overloaded. It happens. You get someone out of long deprivation and something simple hits them. The body’s been braced for harm too long. It’s not weakness. It’s recognition.”

Recognition.

The word sank into Daniel like a pebble dropped into water, small but rippling.

He watched her sip again, slowly now, as if testing whether pain would return. When it didn’t, her shoulders loosened a fraction, something only someone staring too closely would notice.

Daniel was staring too closely.

He did not know why he couldn’t stop.

Maybe it was because he had gone to war believing suffering was always loud. He had expected screams and blood and explosions. He had seen those, yes. But her suffering had been quiet, stitched into the muscles of her throat and the reflexes of her hands. It unsettled him more than he wanted to admit.

It felt like discovering a new kind of wound.

When the day finally quieted when the gate was secured, when the first blankets were distributed, when the Red Cross workers arrived with clipboards and tired smiles Daniel found himself standing outside the camp office, waiting for orders. His boots were soaked. Mud crusted his pant legs. The cold had threaded itself through every layer.

He took his helmet off for a moment and ran a hand through his hair, then put it back on like removing it had been a mistake.

A chaplain walked past, carrying a box of supplies and looking older than his rank should have allowed. He nodded at Daniel.

“You all right, son?”

Daniel hesitated, because answering honestly felt strange.

“I gave a woman water,” he said finally, as if it was a confession.

The chaplain’s brows lifted slightly. “That’s not a sin.”

“She cried,” Daniel added, and he hated how small his voice sounded.

The chaplain did not laugh. He did not look confused. He only nodded slowly, as if he understood something Daniel hadn’t learned yet.

“Sometimes mercy shows you the whole cost,” the chaplain said. “Not just the battlefields.”

Daniel swallowed. He watched his breath fog in front of him. He wanted to argue, to push back, to keep the world simple enough to manage. Instead he said nothing, because nothing was the honest choice.

That night, he wrote a letter home on a piece of Army stationery, his handwriting tight from cold and fatigue. He told his mother he was safe. He told her he had eaten. He told her not to worry.

Then he paused, pen hovering, and wrote one extra line he wasn’t sure he should send.

Today I gave a woman a sip of clean water and she cried like it was the first kind thing she’d ever been offered. I didn’t know water could mean that much.

He stared at the sentence for a long time, then crossed it out with one hard stroke. He folded the letter, sealed it, and told himself it was better not to burden people with things they could not understand.

But crossing it out did not erase it from his mind.

The next morning, the camp looked different. Not fixed. Not healed. Just different.

American soldiers moved through with supplies. Red Cross workers set up tables for registration. Medics walked the lines, checking fevered foreheads, giving out aspirin, distributing thin blankets that still smelled like storage. The prisoners women and men stood in groups, quiet, watching, as if any sudden movement might trigger punishment.

Daniel found the woman again near a water station. She was standing with a cup in her hands, staring at the surface as if the clarity was unnatural.

He approached slowly, careful not to startle her.

“Hey,” he said.

She looked up. Her eyes were red-rimmed but steadier now. She held herself like someone trying to remember how to be visible without becoming a target.

“Hello,” she said.

He realized he didn’t know her name, and the realization bothered him. Names were how you reminded someone they were a person, not a category. He had spent too long calling people “sir” and “ma’am” and “you there.”

“You got a name?” he asked, slow.

She hesitated. Names had been used against her. Names had been written on lists. Names had meant you were found.

Then she saw his face young, tired, awkwardly sincere and something in her softened, not into trust, but into a willingness to try.

“Hanna,” she said.

“Hanna,” he repeated, careful with the sound, as if it mattered. “I’m Daniel.”

She nodded. “Daniel.”

“Where you from?” he asked, then regretted it immediately because where she was from had become an accusation in the world.

“Near Leipzig,” she said cautiously.

Daniel nodded as if she’d said something ordinary, as if place names were not weapons.

“Ohio,” he said, offering his own without being asked. “A town called Marietta. You ever hear of it?”

Hanna shook her head. America was an idea to her more than a place, something printed on maps and whispered about like a rumor. She had heard the word “America” in different tones hope, fear, resentment, fantasy. She did not know how it sounded in an ordinary mouth.

“It’s quiet,” Daniel said, then smiled faintly, like he was embarrassed by how inadequate that sounded. “Rivers. Trees. Summers that smell like cut grass.”

The image landed in Hanna’s mind like a photograph she couldn’t quite believe. Quiet. Rivers. Cut grass. The normalcy of it made her chest ache.

She looked down at her cup. The water was clear. It did not smell. It did not warn her.

Daniel glanced toward the water station and then back at her.

“If you need more,” he said, pointing, “it’s there. Just go.”

The idea of “just go” felt like a foreign language. Water that was simply there, waiting, not guarded, not rationed with cruelty, not mixed with suspicion.

Hanna nodded anyway.

“Thank you,” she said, because gratitude was the only bridge she had.

Daniel hesitated, wanting to say more, then said something that was meant kindly and landed awkwardly.

“You don’t have to be scared of it.”

Hanna’s throat tightened, because she realized she had been scared of everything for so long that being told not to be scared felt like being told not to breathe.

“I know,” she lied softly.

Daniel nodded, accepting the lie because pushing would have been selfish.

Days blurred. The war moved on. Units rotated. Supplies came, then left. People were processed, classified again, reassigned. Hanna was interviewed by an American officer with a translator. She answered questions about her work, about her movements, about what she knew and did not know. Her words were measured because she had learned the wrong detail could become a hook.

Eventually, because she spoke some English and could read and type, she was asked to help translate for other women who couldn’t speak to the Americans at all. At first she refused. She had spent years being used by systems. The idea of being useful again felt dangerous.

Then she watched a young mother with hollow eyes try to explain, in frantic German, that her child had a fever. The American medic didn’t understand. The mother’s panic rose like floodwater.

Hanna stepped forward before she could stop herself. She translated, quickly, clearly. The medic nodded, moved into action. The mother’s shoulders sagged with relief.

Hanna felt something strange in her chest. Not pride. Not satisfaction. Something closer to relevance. She had forgotten what it felt like to matter in a way that helped someone, not in a way that fed a machine.

She began translating more. It gave her a small measure of control. It gave her a role that was not purely passive. It also exhausted her, because every story she heard was another reminder of what the war had done to bodies and minds.

Daniel saw her sometimes, working near the registration tables, translating with a calm that looked borrowed. He wanted to speak to her more, but the days were crowded with orders and movement. He told himself he would find time. He told himself many things in war.

Then one morning, his unit was ordered to move. New assignment. New direction. Another place that needed soldiers.

Daniel found Hanna near the water station again. She was holding a clipboard now, translating for an older woman who kept pointing at a paper like it was trying to accuse her.

Daniel waited until Hanna finished, then stepped forward.

“We’re leaving,” he said.

Hanna blinked. Her mind worked slowly around the word.

“Leaving,” she repeated.

“Yeah,” he said. “Orders.”

She nodded, as if she had expected the world to remove him the way it removed everything else.

He swallowed, awkward, then pulled a small notebook from his pocket and tore out a page. He wrote something on it, quickly, then held it out.

It was an address. His parents’ house in Ohio. The ink smudged slightly from the cold.

“If you ever…” he began, then stopped because the sentence felt impossible. If you ever what? If you ever come to America? If you ever want to write? If you ever want to prove you exist beyond this place?

Hanna stared at the paper. She did not reach for it immediately. Paper had been dangerous for years. Paper had meant records and lists and accusations. Paper had meant you could be found.

Daniel waited, holding it out, not pushing.

Hanna finally took it with two fingers, careful. She folded it once, then again, and slipped it into the inside pocket of her coat.

“Thank you,” she said.

Daniel nodded. He looked like he wanted to say something kind and clever and meaningful. Instead he said the simplest thing he could find.

“Drink the water,” he said quietly. “It’s real.”

Then he turned and walked away, because if he didn’t walk away now, he might do something foolish like cry too.

Hanna watched him go until he became just another soldier among soldiers, then another figure moving through gray air, then nothing.

She touched the paper in her pocket like it might burn.

The war ended, but ending did not mean clean.

Hanna moved through a series of temporary places: displaced persons camps, processing centers, interviews with officials who asked questions like they could sort her into a neat category. She was offered choices that did not feel like choices. Repatriation to a city she was not sure still existed in the way she remembered. Remaining in a camp until paperwork caught up to her life. Applying for relocation if she could find sponsorship, if she could prove she was not dangerous, if she could prove she was worth the trouble.

Worth.

The word haunted her.

In the displaced persons camp, life was made of lines. Lines for food. Lines for blankets. Lines for registration. Lines for medical checks. Some days the lines moved fast, some days they moved like molasses, and no one could explain why.

At night, she lay on a cot under a thin blanket and listened to other women breathe. Some cried quietly. Some laughed too loudly, as if laughter could build walls against memory. Some stared at the ceiling and spoke to no one.

Hanna kept a small notebook. At first she used it only for practical things names, dates, addresses, phrases in English. Then, one night when sleep wouldn’t come, she wrote a sentence she didn’t plan.

Today I drank water that didn’t hurt.

She stared at the sentence afterward as if it belonged to someone else. It looked small and ordinary on paper. It did not capture what it meant. Still, she left it there. It was proof that the moment had happened.

Weeks turned into months. The camp changed faces. Some people left. Some arrived. Aid workers came through Americans with clipboards, British officials, Red Cross nurses, sometimes quiet religious groups who brought small comforts like soap and warm socks and books.

One afternoon, a Quaker woman with gray hair and gentle hands handed Hanna a tin cup of tea and spoke slowly.

“You speak English,” the woman said.

“A little,” Hanna replied.

The Quaker woman smiled. “You can learn more. You can start over.”

Start over.

Hanna wanted to laugh. Start over felt like something you did with a clean slate, not with a body full of memory.

Still, the Quaker woman’s presence was steady. She didn’t speak in slogans. She asked Hanna about what she liked before the war, not what she had suffered. No one had asked Hanna what she liked in years.

“I liked books,” Hanna said cautiously.

The Quaker woman’s eyes brightened. “We have books,” she said, as if this was the most natural thing in the world. “English books. German books. You can borrow.”

Borrow.

The word landed softly. Borrow meant you were expected to return. Return meant the world assumed you would still exist.

Hanna went to the small camp library that had been built out of a converted room. The shelves were mismatched. The books were worn. Still, the smell of paper made something in her chest loosen. She ran her fingers over spines the way some people touch rosary beads.

She chose a thin English novel with simple sentences. She sat by a window where light fell in pale strips and sounded out words quietly to herself. The act was slow and humiliating and comforting all at once.

She began to imagine a future that was not made only of survival.

Then came paperwork opportunities wrapped in requirements. If she wanted to leave Europe, she needed sponsorship. She needed references. She needed someone to vouch that she would not be a burden.

Hanna thought of Daniel’s paper in her pocket. She had kept it through everything, folding it carefully, transferring it to each new coat, each new bag. She had not written. Writing felt like an intrusion. Writing felt like opening a door to disappointment.

One evening, after a long day translating for new arrivals, Hanna sat on her cot and held the paper in her hands. The address was in Ohio, a place she could not picture except through Daniel’s brief description. Rivers. Trees. Summers that smelled like cut grass.

She unfolded the paper, smoothed it with her thumb, and stared at the ink.

Why him?

Because he had stayed. Because he had asked a question softly. Because he had held out water without expecting anything back. Because in a world where kindness had become rare and complicated, his had been simple.

Hanna found a scrap of stationery and a borrowed pencil. She wrote slowly, carefully, English words like fragile stones she didn’t want to drop.

Dear Daniel,

You do not know if you remember me. I am Hanna. You gave me clean water at the camp. I cried. You asked why. I could not explain. I still cannot explain good. But I think about it often. I am alive. I am learning English. Thank you for that day.

She stared at the letter. It felt too small. It felt too heavy. She did not know what she wanted from him. Not rescue. Not friendship, exactly. Something simpler: a line back to the day her body remembered safety.

She added one more sentence.

I hope you are safe too.

Then she folded the letter, sealed it in an envelope, and handed it to an aid worker who promised it would be sent through channels that still worked.

After she let it go, she felt foolish and strangely light.

In Ohio, Daniel received the letter months later. By then, he was no longer in Germany. He was back in Marietta, walking streets that looked untouched by war. The Ohio River slid by in its usual slow way. In summer, kids still jumped off docks and came up laughing. People complained about rain and taxes and the price of beef. The normalcy felt unreal. Daniel felt like a ghost moving through a life that had continued without him.

He had tried to talk about Germany once, over dinner, and his father had cleared his throat and said, “Let the boy eat,” like stories of war were something you could choke on.

Daniel stopped trying.

He went to the hardware store with his mother, helped fix a neighbor’s fence, attended church on Sundays because that’s what people did. He applied for school with the GI Bill because everyone said it was smart. He sat in classrooms and listened to professors talk about economics and literature while his mind drifted back to the camp’s gray sky and the way Hanna had cried over water.

He told himself it was just one moment, one strange moment that would fade. Instead it settled into him like a stone he carried.

The letter arrived on a day when the air smelled like cut grass, the exact smell he had described to her. The irony hit him so hard he had to sit down at the kitchen table.

His mother slid the envelope across to him, curious. “From Germany,” she said, eyes wide as if the word itself was dramatic.

Daniel’s hands shook slightly as he opened it. He read Hanna’s careful English, and something in his chest tightened so sharply he had to exhale slow. The room around him blurred, not because he was crying, not yet, but because he felt the world shift. The moment had been real to her too. It had not been something he invented.

He read the line I am alive again and again.

His mother leaned over his shoulder, reading, then pressed a hand to her mouth.

“Oh,” she whispered, as if she suddenly understood what he had not been able to say at dinner.

Daniel wrote back that night. He kept it simple. He told her he remembered. He told her he was glad she was alive. He told her she did not have to thank him, but he knew she would anyway. He told her his town was small and quiet and there was a river and the water ran clear.

He did not tell her that the letter had made him feel less alone. He did not want to burden her with his feelings when she was still standing in the wreckage of her life.

Their correspondence continued, slow and uneven, dependent on the unpredictable mail channels of a world rebuilding itself. Hanna wrote about the camp library, about learning English words, about the strange feeling of being asked questions by officials who looked tired of being responsible for so many lives. Daniel wrote about school, about his mother’s garden, about the river and the way autumn leaves floated like small boats.

They did not write about ideology. They did not write about blame. They wrote around the war like two people walking the edge of a crater, careful not to fall in.

In time, an opportunity emerged that felt almost unbelievable: a sponsorship program, a family in Pennsylvania willing to sponsor a displaced woman who could work, who could learn, who could contribute. The Quaker woman Hanna had met knew the family. The paperwork moved slowly, then suddenly sped up as if some hidden gear had clicked into place.

Hanna boarded a ship with a small suitcase and a folder of documents that made her official.

The Atlantic was enormous. The water beneath the ship was dark and indifferent, and Hanna had to fight the impulse to fear it. Water was everywhere now. Water surrounded her. She could not control it. She could only breathe and trust the ship to hold.

On the deck, wind tasting of salt, she held the railing and watched the horizon. Other passengers stood nearby, wrapped in coats, their eyes full of the same exhausted hope. An American woman offered Hanna a tin cup of water.

Hanna hesitated out of habit, then took it. The water was clean. Cold. Safe.

She swallowed and felt a familiar tightening in her chest, the old reflex trying to return. This time, she breathed through it. She told her body, quietly, you are not there anymore.

The woman smiled. “You okay?”

Hanna nodded. “Yes.”

Her voice sounded steadier than she felt.

Pennsylvania in late fall was a place of damp air and turning leaves. The Harper family lived in a town where houses had porches and screen doors and yards that looked tended. Their kitchen had a faucet that produced clear water instantly. The first time Hanna heard it run, her heart raced.

The sound was too easy, too generous, like something that couldn’t be real.

Mrs. Harper filled a glass and set it in front of her with the same casualness she might have used to offer salt.

“Here you go,” she said. “You must be thirsty after all that travel.”

Hanna stared at the glass. The water was so clear she could see light through it. Her hands trembled as she lifted it.

Mrs. Harper noticed and softened her voice, not asking questions that would trap Hanna in explanation.

“Honey,” she said gently, “you can drink it. It’s good water. We got a well out back. Clean as can be.”

Hanna took a small sip, then another. The water didn’t hurt. It never hurt. Tears threatened again, but Hanna swallowed them down, ashamed of being the strange foreign woman crying at a kitchen table.

Mrs. Harper did not ask why. She simply set a plate of bread in front of her.

“Eat, sweetheart,” she said. “Take your time.”

That night, Hanna lay in a small upstairs room under a quilt that smelled faintly of soap and sunlight. She listened to the quiet, the American kind of quiet that assumed tomorrow. It was not the battered quiet of Europe. It was whole.

Hanna cried silently into the pillow, not from pain but from the strangeness of being allowed to exist without bracing.

In the weeks that followed, Hanna learned the shape of American days. Breakfast was at a table, not in a line. Coffee was strong and plentiful. People talked about weather the way Europeans used to talk about politics. Children went to school with lunch pails and came home complaining about spelling tests. The complaints felt like music. Ordinary problems were proof of an ordinary world.

Hanna found work in a textile factory first, because factories always needed hands. The work was repetitive and exhausting, but it paid. She saved money in an envelope hidden in a drawer because saving still felt like protection. She wrote letters to Daniel in careful English, telling him she had arrived, telling him she had a bed and clean water and a sponsor family that was kind.

Daniel wrote back with relief that spilled through his words. He was still in Ohio, still studying, still trying to find the line between who he had been before the war and who he was now.

One spring, Daniel visited Pennsylvania on a weekend break from school. He told his mother he wanted to see the state, that he wanted to drive. He did not tell her he wanted to see Hanna. Naming that desire felt too complicated, too loaded. His mother knew anyway. She had read the letters. She had watched him read them, quiet and transformed.

The Harper family welcomed Daniel politely, curious about the young soldier who had written to Hanna across the ocean. Hanna stood in the doorway when he arrived, hands clasped tight in front of her, posture straight like she was preparing for an inspection.

Daniel took off his hat, suddenly awkward, suddenly unsure what they were to each other. The war had created strange relationships, half built from trauma and half built from kindness.

“Hanna,” he said.

“Daniel,” she replied, and the sound of his name in her mouth made something in both of them soften.

They sat at the Harper kitchen table. Mrs. Harper served coffee and pie like she was determined to make the moment ordinary. Daniel looked around, absorbing the details: the checkered curtains, the bowl of apples, the way sunlight fell across the table like a blessing. Hanna watched him the way she had watched the canteen at the fence line wanting to trust, afraid of disappointment.

Daniel cleared his throat.

“I… I got your letters,” he said.

Hanna nodded. “Yes.”

Silence settled, not uncomfortable, just full. Mrs. Harper, sensing it, took the children outside to play, leaving Hanna and Daniel alone with the quiet hum of the refrigerator and the distant sound of a lawnmower.

Daniel glanced toward the sink. “You got water here,” he said, and hated how stupid it sounded.

Hanna looked at the sink too, then back at him. Her eyes were steady now, but the memory still lived in her body.

“Yes,” she said softly. “So much.”

Daniel swallowed.

“I didn’t understand that day,” he admitted. “At the camp. I thought… I don’t know what I thought.”

Hanna’s hands tightened and then loosened. She took a breath, slow, letting the words come the way she had learned to let English come careful, patient, not forcing.

“You asked,” she said. “Why I cry. I could not explain. Not then.”

Daniel nodded, listening like the words were something he had earned.

Hanna’s gaze drifted to the window. Outside, the sky was clean blue. The kind of sky that made you believe in futures.

“In camp,” she said, voice quiet, “my body… always ready. Always waiting for hurt. Water hurt many times. Water sick. Water taste like metal. Sometimes… water smell. I drink anyway. I learn to not feel. Not hope.”

Daniel’s jaw tightened, and Hanna saw something in him she recognized a desire to fix the past, to undo what couldn’t be undone.

“When you give me clean water,” Hanna continued, “my body remember. Before my mind. It is like… my body say, ‘Oh.’ Like… ‘This is how it was.’ And then everything come out.”

Daniel let out a breath he had been holding for years.

“I’m sorry,” he said, and the apology was not for his question, not for his confusion, but for the world that had made water into pain.

Hanna looked at him, and her expression softened into something that wasn’t forgiveness because forgiveness implied blame but into recognition.

“Not your fault,” she said. “But you stay. You did not laugh. You did not go away. That… that matter.”

Daniel nodded, eyes shining, and he looked down quickly because he was still a young man raised to believe tears were private.

They sat in silence for a while, not empty, just full of what had been carried too long.

After that visit, life continued the way life does, one day at a time. Hanna learned English more fluently. She found work in a library eventually, first shelving books, then helping patrons, then earning enough trust that she could manage the front desk. The library became a place where quiet was not fear but comfort. The smell of paper soothed her nervous system in a way she couldn’t explain.

Daniel finished school and found work. He married, had children. He and Hanna wrote less often as years filled with ordinary obligations. But they did not lose each other completely. Every Christmas, Hanna sent a card. Every Christmas, Daniel sent one back.

On some cards, he drew a small river in the corner, a private symbol between them. Hanna, in return, sometimes pressed a tiny dried leaf inside the envelope, as if she could send him a piece of autumn, proof that time kept moving.

Hanna never wasted water.

She washed dishes with the faucet barely cracked open, letting a thin stream do the work. She filled kettles carefully, never more than she needed. She drank slowly, noticing temperature, clarity, taste, the way some people notice music.

Sometimes, late at night, she would wake and walk to the kitchen, her feet silent on the floor. She would turn the faucet on just enough to hear it run. The sound would fill the room softly. Her chest would tighten, not with fear exactly, but with memory.

Then she would turn it off and stand still until her breathing steadied. The world was safe now, but safety was something her body had to practice.

Decades passed. America changed. Streets filled with more cars. Phones became smaller. The library got computers. Hanna learned to use them, cautious at first, then with growing confidence. She watched young people come in and print resumes and search for jobs and complain about slow internet, and she smiled privately at the abundance of their problems.

One summer, a drought hit the area. The town placed restrictions on watering lawns. People grumbled. Hanna listened, sympathetic to the inconvenience, amused by the outrage. She did not judge. People could only measure life by what they had known.

Still, one day in the grocery store she watched a man buy cases of bottled water, stacking them in his cart like armor. His face was anxious.

“Storm coming,” he muttered to the cashier, as if defending himself.

Hanna’s chest tightened. The old reflex. Water as fear.

She went home and filled two pitchers and set them on her counter, not because she believed the water would disappear, but because her body still understood the comfort of being prepared.

That night, she wrote in her old notebook, the one she had carried since the displaced persons camp. The pages were yellowed now. Her handwriting had grown steadier over years, English no longer fragile.

Clean water is ordinary here. Sometimes I forget it is a miracle. Then I remember.

In her later years, Hanna began speaking occasionally at community groups small gatherings at churches and libraries where older people shared stories. She did not describe horrors. She did not trade in graphic details. She spoke about endurance and rebuilding, about the strange way the body holds memory, about how dignity can return in small forms.

She told a room full of high school students once, “You think history is only big things. Battles. Dates. Leaders. But sometimes history is a cup of water.”

They blinked at her, confused, and she smiled gently because confusion was where understanding began.

After the talk, a teenage girl approached Hanna with a water bottle in her hand, twisting the cap nervously.

“My mom says I waste water,” the girl said, half embarrassed. “I leave it running when I brush my teeth.”

Hanna looked at her, not judging, only seeing youth.

“You can change,” Hanna said softly. “Not from guilt. From noticing.”

The girl nodded slowly, as if the word noticing was new.

Years later, Daniel’s wife passed, and he found himself alone in a quiet house. His children were grown. His hair was white. He moved slower now. He spent mornings on his porch watching the river in Marietta slide by. Sometimes he thought about the war the way people think about storms they survived grateful to be past it, startled by how vividly it still lived inside them.

On a winter afternoon, Daniel received a letter from Pennsylvania. The envelope was familiar. Hanna’s handwriting, older now, but still careful.

Daniel opened it with hands that trembled not from cold but from time.

Dear Daniel, it began. I am old now. I think about that day again. I think about your question. Why are you crying. I want to answer better now.

Daniel sat at his kitchen table and read slowly.

Hanna wrote that her body had carried the war longer than her mind. She wrote that safety had arrived like a shock. She wrote that clean water was not only hydration. It was proof. Proof that the world could still be kind. Proof that she was still human.

At the end of the letter, Hanna wrote one line that made Daniel close his eyes.

Thank you for staying.

Daniel cried then, quietly, surprised by himself. He had not cried at the war’s end. He had not cried when he returned home. He had not cried when friends died years later from age and illness. He cried now because he finally understood what the chaplain had meant. Sometimes mercy showed you the whole cost.

Daniel wrote back. His handwriting shook. He told Hanna he had never forgotten. He told her he still thought about the canteen, the mud, the gray sky, the way her tears had made him realize the war had stolen things he hadn’t known could be stolen.

He told her something he had never written before.

Sometimes I turn on my tap and I think about you. I think about how lucky I am. I think about how I didn’t know. I’m sorry I didn’t know. I’m grateful you’re alive.

Hanna read the letter in her small home, now filled with books and quiet. She folded it carefully and placed it in her notebook, the same notebook that still held the first sentence she had ever written about that day.

Today I drank water that didn’t hurt.

She looked at the sentence, then at the new letter, and felt something settle in her chest.

The story had become whole.

Not clean. Not simple. But whole.

On a bright spring morning, Hanna sat at her kitchen table with a glass of water. Sunlight spilled through the window, turning the water into something that looked almost like crystal. She held the glass with both hands, feeling the coolness against her palms.

She took a sip.

It didn’t hurt.

Her body did not collapse. Her throat did not tighten. The water slid down smooth and quiet, like an ordinary thing.

Still, Hanna paused afterward, eyes unfocused, and let herself feel it not as a shock anymore, but as a steady truth.

The world could still be kind.

She did not cry because she was weak. She did not cry because she was broken. If she cried at all now, it was the way you cry when you have carried something heavy for so long you almost forget what it feels like to set it down.

Somewhere in Ohio, Daniel turned on his tap to fill a kettle for morning coffee. The water ran clear. He watched it for a second longer than necessary, then turned it off.

He didn’t know why he always did that pause, notice, breathe until he realized he had learned it from Hanna without ever meaning to. He had learned to notice water. He had learned that ordinary things were only ordinary if your body had never been taught to fear them.

He poured the water into the kettle, set it on the stove, and stared out his kitchen window at the river in the distance.

“Why are you crying?” he had asked once, crouched in mud beside a fence line in a foreign country.

Now he knew the answer.

Sometimes relief arrives so suddenly the body doesn’t know how to contain it. Sometimes safety is so unfamiliar it feels like overwhelm. Sometimes dignity returns in the smallest form a sip of clean water and the body remembers before the mind can explain.

And sometimes, the most shocking truth of all is not that the world can be cruel.

It’s that, even after everything, the world can still be kind.

News

My daughter texted, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.” I didn’t argue. I simply wished them a peaceful holiday and stepped back. Then her last line made my chest tighten: “It’s better if you keep your distance.” Still, I smiled, because she’d forgotten one important detail. The cozy house they were decorating with lights and a wreath was still legally in my name.

My daughter texted me, “Please don’t come over for Christmas. My husband isn’t comfortable, and we need a little space.”…

My Daughter Texted, “Please Don’t Visit This Weekend, My Husband Needs Some Space,” So I Quietly Paused Our Plans and Took a Step Back. The Next Day, She Appeared at My Door, Hoping I’d Make Everything Easy Again, But This Time I Gave a Calm, Respectful Reply, Set Clear Boundaries, and Made One Practical Choice That Brought Clarity and Peace to Our Family

My daughter texted, “Don’t come this weekend. My husband is against you.” I read it once. Then again, slower, as…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him $400 every month to help with care costs and prescriptions. I believed it was the only way I could still be there for him from far away. But when I showed up to visit him without warning, his neighbor simply smiled and said, “Care for what? He’s perfectly healthy and living normally.” In that instant, a heavy uneasiness settled deep in my chest…

For eight years, my son told me his health wasn’t doing well, so I faithfully sent him four hundred dollars…

My husband died 10 years ago. For all that time, I sent $500 every single month, convinced I was paying off debts he had left behind, like it was the last responsibility I owed him. Then one day, the bank called me and said something that made my stomach drop: “Ma’am, your husband never had any debts.” I was stunned. And from that moment on, I started tracing every transfer to uncover the truth, because for all these years, someone had been receiving my money without me ever realizing it.

My husband died ten years ago. For all that time, I sent five hundred dollars every single month, convinced I…

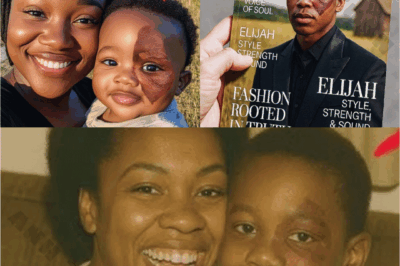

Twenty years ago, a mother lost contact with her little boy when he suddenly stopped being heard from. She thought she’d learned to live with the silence. Then one day, at a supermarket checkout, she froze in front of a magazine cover featuring a rising young star. The familiar smile, the even more familiar eyes, and a small scar on his cheek matched a detail she had never forgotten. A single photo didn’t prove anything, but it set her on a quiet search through old files, phone calls, and names, until one last person finally agreed to meet and tell her the truth.

Delilah Carter had gotten good at moving through Charleston like a woman who belonged to the city and didn’t belong…

In 1981, a boy suddenly stopped showing up at school, and his family never received a clear explanation. Twenty-two years later, while the school was clearing out an old storage area, someone opened a locker that had been locked for years. Inside was the boy’s jacket, neatly folded, as if it had been placed there yesterday. The discovery wasn’t meant to blame anyone, but it brought old memories rushing back, lined up dates across forgotten files, and stirred questions the town had tried to leave behind.

In 1981, a boy stopped showing up at school and the town treated it like a story that would fade…

End of content

No more pages to load