It was the year 1868 when a German missionary, Frederick Augustus Klein, was walking through the Dhiban region, in present-day Jordan.

There he found a block of black basalt more than a meter high, covered with ancient inscriptions.Local inhabitants used it as a simple firestone, unaware that they held one of the most devastating archaeological discoveries for biblical skepticism.

It was the Mesa Stele, also known as the Moabite Stone.

The stele was commissioned by Mesha, king of Moab, in the 9th century BC.

Moab was not an ally of Israel.

He was his enemy.

The book of 2 Kings chapter 3 itself describes the conflict between Israel and Mesha.

This stone was not inscribed to confirm the Bible, but to celebrate the rebellion of Moab and glorify their national god, Chemosh.

However, in doing so, Mesa left behind something he could never control: an independent testimony that coincides with the Hebrew Scriptures.

In its 34 lines, the stele mentions real historical names: Omri, king of Israel, cities such as Atarot, Nebo and Medeba, all known from the Bible and confirmed by modern archaeology.

The chronology fits precisely into the Iron Age, a time of regional wars between small kingdoms.

Two different stories, two opposing sides, but the same central events.

It’s not a myth.It is a shared history from opposite sides of the battlefield.

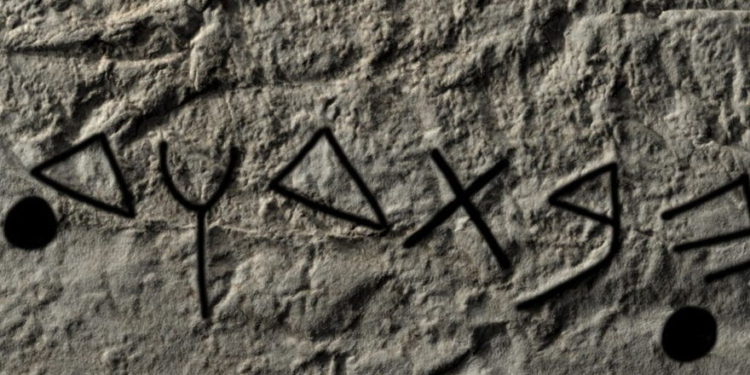

But the detail that shakes the foundations appears in a specific line.

Mesa writes, without ambiguity:

“And I took the vessels of Yahweh and brought them before Chemosh.”

There it is.

Carved in stone.

Yahweh.

Not a generic god, not an abstract divinity.

The personal name of the God of Israel, the same one that appears more than six thousand times in the Hebrew Bible.

And it wasn’t Israel who wrote it.

He was a pagan king, an enemy, mocking, trying to humiliate the deity of his adversaries.

But in doing so, he confirmed his historical existence.

This is a phenomenon that historians call hostile corroboration: when an enemy source, with no intention of supporting a story, ends up confirming it.

If a Hebrew scribe had written this, critics would have dismissed it as religious propaganda.

But Mesa had no reason to validate the Israelite faith.

And yet, he did it.

For decades, some academic currents maintained that the name Yahweh was a late invention, developed during or after the Babylonian exile, in the 6th or 5th centuries BC.

According to these theories, Israeli monotheism would be a later evolution.

But the Mesa Stele, dated to around 840 BC

, destroys that narrative.

It demonstrates that Yahweh was already recognized as the national God of Israel centuries before the exile, with a temple, rituals, and sacred objects.

The Egyptologist and expert on the Ancient Near East Kenneth A.

Kitchen stated that the stele is one of the strongest archaeological confirmations of the biblical account precisely because it comes from an enemy.

And archaeologist William Dever, hardly suspected of fundamentalism, acknowledges that this artifact forces both believers and skeptics to accept an uncomfortable truth: Yahweh was not a late invention.

Mesa believed that by defeating Israel he had also defeated his God.

That is why he boasts of having taken the sacred utensils from the temple of Yahweh and profaned them before Chemosh.But in his pride, he preserved the name he intended to humiliate.

The stone that was meant to be mocked became an eternal witness.

Empires often wipe out their enemies.

The Assyrians, Babylonians, and Egyptians rewrote history to aggrandize themselves and eliminate all legitimacy from the vanquished.

In that context, mentioning an adversary’s god was not a trivial gesture; it was acknowledging his importance.

And Mesa did it.

Unwittingly, he left evidence that Yahweh was already feared, known, and recognized even outside of Israel.

Here, archaeology ceases to be a decorative support for faith and becomes an uncomfortable voice.

Because this stone does not believe, does not preach, and does not evangelize.

It simply exists.

And its existence challenges the idea that the Bible is a late construction without historical roots.

Jesus said in Luke 19:40: “If these keep silent, the stones will cry out.

“And that’s exactly what’s happening here.”

It is not a prophet who speaks.

He is not a priest.

It’s a stone.

A stone that went through 3.

000 years of dust, wars, empires and skepticism to say one thing with brutal clarity: the name of Yahweh could not be erased.

This is not just a test for the mind, it is a confrontation for the heart.

If even the enemies of Israel preserved the name of their God, if history engraved it in stone when no one tried to defend it, then the question is no longer whether the Bible has a foundation.

The question is different: what will you do with a truth that even your adversaries could not silence?

The stone is still there.

The name is still there.

And the voice, though ancient, still speaks.

News

“Uncle Keanu… can I stand with you just once?” — The Soft Question That Silenced an Entire Stage

The Moment No One Heard — Until Everyone Felt It It wasn’t shouted. It wasn’t amplified. It didn’t come with…

“You Don’t Get to Rewrite My Character on Live TV” — The Moment Keanu Reeves Forced Hollywood to Rethink the Power of Daytime Television

A Line That Stopped the Studio Cold It was supposed to be another harmless daytime TV moment. A light interview….

BREAKING NEWS: Keanu Reeves and Alexandra Grant share magical ice-skating date night at Rockefeller Center ⚡ WN

Keanu Reeves and Alexandra Grant just turned Rockefeller Center into their own private love story. In a moment straight out…

BREAKING NEWS: Keanu Reeves named one of TIME’s 100 Most Influential People for something rare—kindness

Keanu Reeves didn’t make TIME’s 100 Most Influential People of 2022 list because he shouted the loudest, chased power, or…

BREAKING NEWS: Keanu Reeves secretly rented Linda Evangelista’s Chelsea penthouse — now it’s for sale at $7.99M ⚡

While captivating theatergoers in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Keanu Reeves was living a very different kind of existential dream — inside a…

BREAKING NEWS: Ruben Östlund Defends Spoiling His Own Film—and Explains Why Audiences Don’t Care

Ruben Östlund Shocks Audiences, Defends Spoilers, and Turns Keanu Reeves Into a Deadpan Nightmare in The Entertainment System Is Down Ruben…

End of content

No more pages to load