In 1943, she was still a seamstress.

Her name was Analisa Weber, and for most of her adult life, her world had been measured in fabric lengths, needle pricks, and the steady rhythm of machines inside a textile factory near the Port of Hamburg. She stitched uniforms there—gray wool, stiff collars, endless rows of buttons—working under fluorescent lights that buzzed even when the city outside trembled from distant explosions.

She worked not out of belief, not out of loyalty, but because work meant ration cards, and ration cards meant survival. She worked while raising two children alone in a city that was slowly, methodically being erased.

The Reich’s propaganda had told her what to expect from the British.

Cruelty. Revenge. Punishment befitting enemies who deserved it.

She listened because listening was unavoidable. Posters were everywhere. Radio broadcasts crackled through walls. Rumors moved faster than bombs. She had prepared herself for the worst long before the first British soldier ever set foot on Hamburg soil. She taught her children to hide when aircraft engines passed overhead, to stay silent in cellars, to never look soldiers in the eyes if occupation ever came.

Survive first. Feel later.

When the occupation finally arrived, it was not savage.

It was bureaucratic.

British soldiers established checkpoints with a precision that felt almost sterile. Notices appeared in German and English, taped to walls that still stood. Lines formed. Tables were set up. Paperwork multiplied. The city was defeated, yes—but not raging. The men in uniform looked exhausted rather than triumphant, hollow-eyed rather than vengeful.

The system was designed for control, not retribution.

But control did not mean food.

Control did not mean shelter.

Control did not mean survival.

Hamburg had been shattered long before the surrender papers were signed. The bombing had destroyed Analisa’s apartment building—not directly. A firebomb had hit the structure next door, and the flames had spread like something alive, devouring wood, fabric, memory.

By the time she had dragged her children down the stairwell and into the street, everything they owned was gone.

Clothing. Documents. Family photographs. The ration coupons she had hoarded for weeks.

All of it reduced to ash.

They moved into the cellar of a partially collapsed building six blocks away, a space once meant for coal storage. Eleven families shared it. Nearly forty people breathed the same stale air, slept on the same cold ground, whispered through the same darkness.

Privacy was impossible.

Safety was an illusion.

But there were walls—some of them—and a ceiling that hadn’t fully given way. That alone made them luckier than many.

By May 1945, Hamburg was a city of survivors trying to understand what survival even meant now that the war was officially over.

Germany surrendered on May 8.

The aftermath was worse.

There was no functioning food distribution system. No real infrastructure. No civilian authority with teeth. Survival depended on British military channels or the black market, and the black market required something to trade.

Analisa had nothing.

No jewelry. No valuables. She had sold everything months earlier—wedding rings, heirlooms, buttons pried from old coats. Whatever hadn’t been sold had burned.

She had no connections, no favors owed, no secret networks. She had been too busy working, too focused on keeping her children alive to cultivate relationships that now mattered more than money.

All she had left were her children.

And hunger.

Leisel stopped asking for food three days ago.

That terrified Analisa more than bombs ever had.

When a five-year-old stops asking for food, it isn’t patience. It isn’t maturity. It’s weakness. It’s the body surrendering quietly.

Max still whimpered sometimes, but even his cries had lost urgency. They had become thin, mechanical sounds, like something his body produced out of habit rather than need.

On May 10, Analisa made a decision.

She would go to the British aid station.

She would beg if necessary.

She would humiliate herself if that was the price.

Pride was a luxury for people whose children weren’t starving.

She left Leisel and Max with Frau Schneider, an elderly woman who shared the cellar. Schneider had no food either, but she could watch them while Analisa went out.

“Don’t expect mercy,” the old woman warned quietly. “The British hate us. We bombed them first. They won’t forget.”

Analisa said nothing. She had no energy for fear that didn’t feed children.

The walk to the aid station was three blocks.

It took twenty minutes.

Not because of distance, but because of rubble, craters, and a body weakened by weeks of starvation. Every step felt measured. Every movement was deliberate, conserving energy she didn’t have.

The aid station was organized chaos.

British soldiers stood behind tables, distributing something—food, documents, supplies—to long lines of Germans who waited with the patience of people who knew there was no alternative.

Signs were posted in German, explaining procedures Analisa barely understood. Registration. Authorization. Documentation.

A system existed.

She did not know how to enter it.

Everyone in line carried papers.

She had none.

After thirty minutes of watching, she approached a soldier standing guard near one of the tables.

He was young—maybe twenty-three. Corporal stripes on his sleeve. A rifle slung over his shoulder. He looked tired but alert, professional rather than hostile.

She spoke in halting English learned years ago in school, badly conjugated, worse pronounced.

“Please, sir. My children. No food. Please help.”

The soldier looked at her for a long moment, his expression unreadable.

“You need to register,” he said. “Get authorization papers. Then you receive rations.”

“Where?” she asked. “How?”

“Registration center. Two miles east. Bring identification documents.”

“I have no documents,” she said quickly. “Burned. Fire. My home.”

Something shifted in his expression—not cruelty, not anger, but exhaustion. The look of someone who had heard this story a hundred times and had nothing left to offer it.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Without documents, without registration, I can’t authorize distribution. Those are the regulations.”

“But my children—”

“I’m sorry.”

He turned away.

Analisa stood there, feeling something inside her collapse.

The food existed.

The system existed.

She could not access either.

She walked back to the cellar empty-handed.

Frau Schneider took one look at her face and understood.

Leisel was asleep—the deep, unnatural sleep of malnutrition. Max whimpered faintly, a sound that had become background noise.

That night, Analisa did not sleep.

She lay on the cellar floor, staring into darkness, turning impossible choices over in her mind.

The black market. No goods.

The registration center. No documents.

Begging again. Regulations.

On May 11, something changed.

The British soldier from the aid station—Corporal James Mitchell, though she did not yet know his name—finished his shift and did something he was not supposed to do.

He left his post.

He walked into the ruins of Hamburg, following a rough mental map of where the German woman had come from.

He found her by accident—or perhaps by instinct sharpened by war.

She was emerging from a cellar entrance, carrying a child who looked like a skeleton wrapped in skin.

“Frau,” he called gently. “The woman from yesterday.”

Analisa froze.

Fear surged first. Why was he here? Why had he followed her?

Mitchell approached slowly, hands visible.

“How many children?” he asked.

“Two.”

“How old?”

“Five. Three.”

He reached into his coat.

She tensed.

Then he pulled out a cloth-wrapped bundle and placed it in her hands.

Bread.

Half a loaf.

Cheese. Four ounces, maybe.

Not much by peacetime standards.

In Hamburg, May 1945, it was wealth.

“For your children,” he said quietly. “My ration. I didn’t eat it.”

“Why?” she asked in German.

He understood anyway.

“I have a sister,” he said after a pause. “She’s five. If Britain had lost… if she was starving… I would want someone to help her. Even if that someone was German.”

Analisa cried then—real tears, the first in weeks.

“Thank you,” she whispered. “Danke.”

“I can’t do this officially,” he said. “But I can do this.”

He turned to leave, then stopped.

“I’ll come back in two days. Same time. If I can bring more, I will.”

He walked away before she could respond.

She stood there, holding bread, cheese, and something unfamiliar.

Hope.

She returned to the cellar holding the bread and cheese like something fragile, afraid it might disappear if she moved too fast.

Frau Schneider watched her unwrap the cloth with narrowed eyes, suspicion etched deep into lines carved by years of scarcity.

“Where did you get that?” the old woman asked.

“A British soldier gave it to me.”

The cellar went quiet.

“A British soldier?” Schneider repeated. “Why would a British soldier give food to a German?”

Analisa shook her head. “I don’t know.”

She didn’t try to explain further because she didn’t understand it herself. All she knew was that the rules she had believed in—the ones drilled into her by propaganda, fear, and survival—had cracked. One man had looked at her children and seen children, not enemies.

She fed them carefully. Too much food too fast could be dangerous. She broke the bread into small pieces, spread thin slivers of cheese. Leisel ate slowly, mechanically, as if chewing were a task she had to remember how to perform. Max ate, swallowed, and almost immediately fell asleep, his body choosing digestion over consciousness.

That night, for the first time in weeks, Analisa slept.

Not deeply. Not peacefully. But without the sharp edge of terror pressing against her ribs.

Two days later, on May 13, Mitchell returned.

Same time. Same place.

This time he brought more.

Bread again. Canned meat. Powdered milk. His ration, and part of another ration he had traded for.

“I told my mates,” he explained quietly. “About your children. Three of them contributed.”

Analisa stared at the supplies, then at him.

“I don’t understand,” she said. “Why help us?”

He shrugged, an almost embarrassed gesture.

“Because helping is a choice,” he said. “And we can choose to be more than what the war made us.”

He stayed only a moment longer, reminding her again that he couldn’t do this officially, that regulations prohibited unauthorized distribution and fraternization. Each time he said it, his tone made clear how little that mattered to him now.

Over the next week, he came three more times.

Each visit brought food.

Each visit brought the same warning.

Each visit brought relief that felt increasingly dangerous, because hope had a way of making loss sharper.

On May 18, Mitchell didn’t come alone.

He brought another soldier, older, with a red cross on his armband and a medical bag slung over his shoulder.

“This is Private David Kemp,” Mitchell said. “Medic.”

He looked down at Max, who lay curled against Analisa’s side, eyes half open, too tired to be curious.

“Your youngest,” Mitchell said gently. “He needs to be examined.”

Kemp knelt in the dirt of the cellar, checked Max’s pulse, his breathing, the color of his gums. He asked questions through Mitchell’s translation, questions Analisa struggled to answer because hunger had blurred time into something shapeless.

Finally, Kemp straightened.

“He needs proper medical attention,” he said. “Hospital care.”

“The British military hospital?” Mitchell asked.

Kemp grimaced. “They don’t admit German civilians. You know the regulations.”

Mitchell nodded once. Then said something that would change everything.

“Then we need to change the regulations.”

That evening, Mitchell went to his commanding officer, Captain Robert Thornhill.

The office was dim, paperwork stacked high, the smell of damp stone and cigarette smoke heavy in the air.

“Sir,” Mitchell said. “I need to report a situation requiring medical intervention.”

Thornhill looked up. “Go on.”

“German civilian child. Age three. Severe malnutrition. Possible organ damage. He needs hospitalization.”

“There are German hospitals,” Thornhill said.

“What’s left of them?” Mitchell asked quietly. “No staff. No supplies. Not in this sector. Sir, the child will die without immediate care.”

Thornhill studied him.

“You’ve been giving your rations to German civilians,” he said.

Mitchell didn’t deny it. “Yes, sir.”

“That’s against regulations.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

Mitchell held his gaze.

“Because the children didn’t start this war,” he said. “Because if we’re supposed to be better than the Nazis, we have to act like it.”

Silence stretched between them.

Finally, Thornhill set down his pen.

“Write it up,” he said. “Humanitarian medical exception. I’ll forward it up the chain. But if this comes back on you, I can only protect you so much.”

“Understood, sir.”

The request moved slowly, grinding its way through layers of bureaucracy that had not yet decided what mercy looked like in defeat.

On May 20, authorization came through.

Max Weber. Age three. German civilian. Authorized for admission to British Military Field Hospital for treatment of severe malnutrition.

Mitchell delivered the news himself.

“You’re going to the hospital today,” he told Analisa.

She didn’t understand the rest of his words. She only understood that her son might live.

She wept openly.

The transport took thirty minutes.

Analisa rode in a British military vehicle with Max in her arms and Leisel pressed against her side. Soldiers stared as they passed—German civilians in a British truck were unusual, almost scandalous.

At the field hospital, a nurse named Sergeant Patricia Walsh was waiting.

She had the steady hands and tired eyes of someone who had seen too much suffering to waste time on judgment.

“How long has he been malnourished?” she asked.

“Weeks,” Analisa said. “Maybe months.”

Walsh nodded. “We’ll start slowly. Fluids first. His system needs time.”

Over the next three days, Max received care that felt miraculous. Intravenous fluids. Careful nutrition. Monitoring.

Analisa stayed beside him constantly.

No one told her to leave.

Leisel stayed too.

Walsh brought crayons. Food. Kindness that required no translation.

On the third day, Walsh asked Analisa to come with her.

“We can’t treat everyone,” she said through a translator. “But we can’t let them die either. What if we trained German mothers to help? You know what this looks like. You’ve lived it.”

“Why trust me?” Analisa asked.

Walsh smiled slightly.

“Because Corporal Mitchell did.”

That conversation became the beginning of something unprecedented.

British medics and German mothers working together.

Cellars turned into clinics.

Survival turned into structure.

By June, over three hundred children had been stabilized.

In July, the program became official.

Mitchell was promoted.

Analisa became the German coordinator.

Max recovered fully.

Years later, letters crossed borders.

In 1952, Mitchell returned to Hamburg.

“We built something,” he said.

“We did,” Analisa replied.

James Mitchell died in 1971.

Analisa Weber died in 1989.

But what they created lived on.

Because sometimes the most radical act after war is not punishment.

It is choosing to share bread.

The collaboration should not have worked.

By every rule the occupation authorities lived by, it should have collapsed under its own contradictions. Former enemies were not meant to cooperate this closely. German civilians were not meant to walk freely into British medical facilities, even under supervision. Regulations existed precisely to prevent blurred lines, to maintain order in a world that had just torn itself apart.

And yet, the work continued.

It continued because children kept appearing in cellars with hollow eyes and swollen bellies. It continued because British medics had supplies but not reach, and German mothers had reach but no supplies. It continued because neither side could solve the problem alone, and both sides knew it.

Analisa learned quickly.

She learned how to recognize the signs of severe malnutrition before they became fatal. How to ration food without shocking fragile bodies. How to explain, patiently and without blame, to mothers who were already drowning in guilt that starvation was not a moral failure but a circumstance imposed by collapse.

She learned British procedures, their clipped efficiency, their insistence on records and lists. She learned which officers were sympathetic and which ones needed persuasion framed carefully as logistics rather than emotion. She learned how to stand straight in rooms where uniforms still triggered fear, how to speak calmly even when her hands trembled.

Mitchell watched her transformation with quiet admiration.

“You were already strong,” he told her once, during a rare moment when they stood outside the hospital, watching trucks unload supplies stamped with American markings—cornmeal, powdered eggs, tins of Spam shipped across the Atlantic as part of the vast Allied relief effort. “You just didn’t know where to put it.”

Analisa looked at the crates, at the English words printed in bold black ink, and thought of how strange it was that food grown and packed in places she would never see—Kansas, Iowa, factories along rivers she could barely imagine—now meant life for children in the ruins of Hamburg.

Strength, she was learning, did not always announce itself.

Sometimes it arrived quietly, wrapped in bureaucracy, carried by people who chose to bend rules instead of hiding behind them.

By late summer, the city looked different.

Still broken. Still scarred. But moving.

Rubble was cleared. Temporary markets formed. Children began to play again, their laughter tentative at first, as if unsure whether joy was allowed.

Max ran.

He ran clumsily at first, legs weak, balance uncertain, but each week he grew stronger. His cheeks filled out. His eyes brightened. By August, he was no longer the child Mitchell had carried in his arms like something made of glass. He was a boy, curious and loud, obsessed with a battered football someone had found in the debris.

Leisel changed too.

She began asking questions again. About school. About why the British spoke the way they did. About whether airplanes would ever come back, and if they did, whether they would bring food instead of bombs.

Analisa answered what she could.

Some things had no answers yet.

In September, a letter arrived.

It was addressed carefully, formally, delivered through official military channels.

Dear Mrs. Weber,

I hope this letter finds you and your children in continued good health. I wanted you to know that what began with sharing my ration has led to something much larger than either of us expected. I have been reassigned to assist in establishing similar programs in other cities within the British zone. What we created in Hamburg is being used as a model.

Thousands of children are receiving help because you were willing to trust an enemy soldier’s kindness. Thank you for showing me that individual actions can change systems.

Please take care of Max and Leisel. They are lucky to have you.

With respect,

James Mitchell

Analisa read the letter several times.

She folded it carefully and placed it with the few possessions she had managed to rebuild since the fire. She wrote a reply that night, her German translated into English by one of the volunteers.

Dear Sergeant Mitchell,

Thank you for seeing my children as children rather than enemies. Thank you for choosing to help when regulations said you should not. You were told to control us, not care for us, and you chose differently.

I will tell my children about you for the rest of my life. I will teach them that enemies in war can become partners in peace. That humanity is always a choice.

With gratitude I cannot fully express,

Analisa Weber

They wrote to each other for years.

Not often at first—paper was scarce, addresses unreliable—but enough to maintain a thread between two lives that had intersected under extraordinary circumstances. Mitchell wrote about Britain, about Liverpool’s docks, about training programs for vulnerable families that he wanted to build when the army finally released him. Analisa wrote about Hamburg, about rebuilding, about the slow, exhausting process of turning emergency aid into permanent public health structures.

In 1947, the British military government began transferring control of humanitarian programs to German civilian authorities.

Analisa was hired by the Hamburg public health department.

She was paid modestly. She was given an office that smelled of dust and fresh paint. She was handed responsibility that would have been unthinkable two years earlier.

She accepted it without ceremony.

This was not ambition. This was continuation.

Mitchell returned to Britain in 1948.

He became a social worker, specializing in programs for children who had fallen through systems designed more for order than care. When asked where he had learned to trust communities instead of managing them, he spoke of Hamburg.

In 1952, he returned.

The city barely resembled the place he had left. Buildings stood where cellars had once been the only refuge. Offices replaced ruins. Analisa met him in a government building that still smelled faintly of ink and coal smoke.

“You’ve built something remarkable,” he said.

“We built it,” she replied.

They walked the city together.

Max and Leisel—now ten and eight—walked ahead, arguing about who would get the football first. Mitchell knelt down to Max’s level and smiled.

“Your mother is a remarkable person,” he said.

Max frowned, confused. “Mama just does her job.”

Mitchell laughed softly. “Then remember this. Some jobs matter more than people realize.”

They stayed in contact for decades.

The letters grew less frequent but no less meaningful. Life filled the spaces between correspondence. Marriages. Children. Responsibilities that crowded out reflection.

In 1968, they met again at a conference on community health.

They sat side by side, two elderly professionals listening to presentations built on foundations they had laid without intending to.

“Do you think we succeeded?” Mitchell asked during a break.

Analisa gestured around them. “We’re here. The children lived. The programs exist. I’d say yes.”

James Mitchell died in 1971.

Analisa Weber died in 1989.

But their story did not end with them.

It lived in policies. In practices. In the quiet assumption, now taken for granted, that humanitarian care works best when people are treated as partners rather than problems.

It began with bread.

And with a choice.

Time had a way of sanding down the sharpest edges of memory, but it never erased them completely.

For Analisa, the years after the occupation blurred into one long season of rebuilding. Not the dramatic kind shown in photographs or speeches, but the quieter work of paperwork, meetings, and difficult conversations with families who no longer trusted systems of any kind. Hunger left scars that did not always show on the body. Some children ate compulsively for years afterward. Some mothers never stopped counting bread slices, even when shelves were full again.

Analisa understood them.

She never forgot the feel of that first half loaf in her hands. The weight of it. The way it had felt heavier than it should have, as if it carried more than calories. She sometimes wondered whether Mitchell understood what he had placed in her palms that day. Not just food, but permission to believe that the future might contain something other than endurance.

Her office at the Hamburg public health department overlooked a street that had once been nothing but rubble. Now it carried trams and bicycles and the ordinary noise of life reasserting itself. On quiet afternoons, she would pause her work and watch people pass, wondering how many of them knew how close the city had come to losing an entire generation of children.

The collaboration model they had built spread quietly.

No monuments were raised for it. No grand ceremonies marked its replication. It simply appeared, city by city, folded into new regulations and pilot programs, justified in dry administrative language that masked how radical it once had been. British officers cited efficiency. German officials cited necessity. Historians would later cite precedent.

But none of those words captured what it felt like in 1945 to walk into a cellar knowing you might be the first person in weeks to bring real food.

Mitchell’s letters, when they arrived, carried a different tone as the years went on.

At first, they were cautious, formal, shaped by the habits of military correspondence. Over time, they softened. He wrote about his work in Liverpool, about neighborhoods hollowed out by poverty rather than bombs, about children whose hunger looked different but felt familiar.

“The uniforms change,” he wrote once, “but the problem doesn’t. Systems fail quietly. People notice too late.”

Analisa replied with stories of her own. About German mothers who still flinched at the sight of British accents. About young doctors who had no memory of the war and struggled to understand why older patients distrusted authority so deeply.

They never romanticized what had happened.

Neither pretended that kindness had erased guilt, or that cooperation had absolved history. They spoke instead of responsibility—ongoing, unglamorous, resistant to closure.

In 1954, Analisa remarried.

She did not write about it immediately. When she finally mentioned it, she framed it practically, almost apologetically, as if happiness required justification.

Mitchell wrote back with warmth.

“You deserve a life that contains more than memory,” he said. “I’m glad you found someone willing to share the present.”

They grew older.

The children grew.

Max became tall and restless, fascinated by machines and movement. He wanted to understand how things worked, how systems were built and repaired. Leisel gravitated toward books, toward stories of places far from Hamburg. She would later say that her earliest memory was not hunger, but the sound of a British nurse humming softly while coloring with her.

When Mitchell returned to Hamburg in 1968 for the conference, the two of them sat through presentations filled with charts and data. Terms like “community-based intervention” and “cross-sector collaboration” floated through the air, stripped of the urgency that had once given them meaning.

During one panel, Mitchell leaned toward Analisa.

“They make it sound so clean now,” he murmured.

She smiled. “That’s how you know it worked. No one remembers how desperate it was.”

They spoke afterward with younger professionals who listened politely, some with genuine interest, others already distracted by the next appointment. Analisa recognized the look. Progress always bred a kind of forgetfulness.

Before Mitchell left that time, they walked together through a small park near the river.

“Do you ever think about that first day?” he asked.

“Every day,” she said. “Not with pain anymore. With responsibility.”

He nodded. “I think about what would have happened if I hadn’t turned back.”

“Someone else might have,” she said gently.

“Maybe,” he replied. “But maybe not in time.”

When he died in 1971, the news reached her by letter.

She sat at her desk for a long time afterward, the paper trembling slightly in her hands. The obituary spoke of service, of dedication, of innovation. It did not speak of bread.

That was all right.

Some stories were not meant for headlines.

She wrote to his family.

Not a long letter. Not dramatic.

She told them that their father had saved her son’s life. That his choices had rippled outward, touching thousands. That his refusal to let regulations outweigh conscience had mattered more than he ever knew.

At his funeral, his daughter told the story anyway.

Analisa never heard the words, but she felt them, carried forward through the quiet confirmation that came later, when people wrote to her saying, “We heard about what he did in Hamburg.”

She retired in the early 1980s.

Her office was cleaned out by younger colleagues who handled her files with reverence they did not fully understand. The photograph of Max in the hospital bed was archived. The letters were cataloged. Her work became history.

In her final years, when illness narrowed her world again, Leisel would sit by her bed and read aloud from newspapers or books.

One evening, she asked, “Do you regret trusting him?”

Analisa considered the question carefully.

“No,” she said. “Trust is never the mistake. Only what we do with it can be.”

Her last request, spoken quietly, was simple.

“Tell James’ family it mattered,” she said. “Tell them that sharing bread led to saving thousands.”

When she died, Hamburg no longer resembled the city that had once buried her children under rubble and hunger.

But the archives remembered.

A photograph. A letter. A footnote in a policy study.

And the knowledge, passed down in ways no document could fully capture, that sometimes the world does not change because systems evolve.

Sometimes it changes because one person refuses to look away.

Because someone shares what they have when they could keep it.

Because humanity, even in the aftermath of war, remains a choice.

Years later, historians would argue about dates, directives, and policy shifts.

They would debate when the British occupation truly softened, when humanitarian considerations began to outweigh punitive instincts, when cooperation replaced control as the dominant framework. They would cite memos, minutes, official directives stamped and filed in neat folders.

None of those documents mentioned a starving woman standing at the edge of an aid station with no papers.

None recorded the moment a young corporal decided that regulations were less important than a child who might not live another week.

History often prefers clean lines.

Real change rarely follows them.

What happened in Hamburg did not announce itself as a turning point. It arrived quietly, almost invisibly, carried by people who were too tired, too hungry, or too overwhelmed to imagine themselves as agents of anything larger than survival. It grew not because it was inevitable, but because enough individuals chose not to stop it when it appeared.

The British soldier who shared his ration did not believe he was starting a movement. He believed he was feeding two children.

The German mother who accepted it did not believe she was laying groundwork for a public health model. She believed she was keeping her son alive through another night.

The nurse who bent visitation rules did not believe she was rewriting policy. She believed families healed better together.

The officer who signed the authorization did not believe he was reshaping occupation doctrine. He believed a child should not die to preserve precedent.

Each decision was small.

Each decision was reversible.

Together, they became irreversible.

As the decades passed, the story changed shape depending on who told it.

In academic circles, it became a case study in post-conflict collaboration. In medical training, it was cited as an early example of community-based care under extreme resource constraints. In Hamburg, among older families, it lived as a rumor that felt almost like a myth—that once, after the war, the British helped.

For Max and Leisel, it was simply family history.

They grew up in a Germany that insisted on remembrance, but also on rebuilding. They learned about guilt and responsibility in classrooms, about systems and structures, about how ordinary people were pulled into extraordinary cruelty. But at home, they learned something else alongside it.

They learned that responsibility did not end with acknowledgment.

It continued in action.

Max became an engineer. He liked systems that could be tested, improved, repaired. He volunteered quietly, never speaking publicly about why hunger programs mattered to him. When asked, he would say only that he had been very sick as a child and had been lucky.

Leisel became a teacher. She taught history to students who had no living memory of war. When lessons turned abstract, she told stories. Not heroic ones. Human ones. About fear. About choice. About the difference one person could make without ever intending to be remembered.

Neither of them met James Mitchell again after childhood.

Neither needed to.

His presence lived in the way their mother approached the world—with firmness, empathy, and an unshakable refusal to dehumanize. It lived in the assumption that help was not weakness, and that trust, once broken on a societal scale, could still be rebuilt person by person.

In Britain, Mitchell’s name faded too.

Social work is not a profession that preserves its heroes loudly. Programs evolve. Staff turnover. Methods are updated. But fragments of his approach survived in training manuals, in quiet institutional memory passed from mentor to student.

He never sought credit.

Those who worked with him later would remember him as insistent, patient, and deeply allergic to excuses framed as policy. He had little tolerance for arguments that began with “That’s not how it’s done.”

When pressed, he would sometimes say, “Then perhaps it should be done differently.”

The older he grew, the less he spoke about the war.

But he never forgot Hamburg.

When his daughter once asked him why he kept a faded photograph of a German woman and two children in his desk drawer, he answered simply, “Because that’s when I learned what my job really was.”

After his death, that photograph was returned to Analisa.

She held it for a long time.

Not because it captured a moment of triumph, but because it captured uncertainty—people standing at the edge of something that could have gone another way. People who had not known yet whether kindness would be enough.

In the end, the field hospital where Max was treated was demolished.

No plaque marked the spot. No guidebook pointed it out. The ground was repurposed, built over, absorbed into a city that had learned how to move forward without erasing what lay beneath.

But in the Hamburg public health archives, the record remained.

A report.

A photograph.

A letter explaining how one child’s treatment became a model for saving thousands.

Researchers would study it.

Students would reference it.

Most readers would skim past it.

And yet, the truth endured.

Two days after a German mother begged a British soldier for food, he returned with more than bread.

He returned with medicine.

With partnership.

With the willingness to violate procedure when procedure prevented help.

With the courage to see enemies as human beings worth saving.

That choice—small, quiet, almost invisible—reshaped lives, policies, and futures in ways no one present could have predicted.

The regulations said no fraternization.

No unauthorized distribution.

No German civilians in military hospitals.

Humanity said otherwise.

One soldier listened.

One nurse agreed.

One mother trusted.

One officer signed.

And thousands of children lived.

Sometimes the most important thing you can do is share what you have when someone is desperate.

Sometimes the most important thing you can do is accept kindness even when it comes from an unexpected source.

And sometimes, what shocks us most is not cruelty from enemies, but compassion.

Compassion that grows.

Compassion that spreads.

Compassion that outlives the war that made it necessary.

Because systems do not change on their own.

They change when individuals decide that conscience matters more than compliance, and when those decisions, repeated often enough, become the new rule.

Humanity, even in the aftermath of humanity’s worst failures, remains a choice.

And sometimes, that choice begins with something as ordinary—and as extraordinary—as sharing bread.

News

Elon Musk Lands $13.5M Netflix Deal for Explosive 7-Episode Docuseries on His Rise to Power

In a move that’s already sending ripples across the tech and entertainment worlds, billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk has reportedly signed…

“MUSIC OF QUARKS”: Elon Musk Unveils Technology That Turns Particles Into Sound – And The First Song Is So Beautiful It Will Amaze Everyone!

In a revelation that has shaken the scientific world to its core, Elon Musk has once again stepped beyond the limits…

The Promise He Never Knew He’d Make

Elon Musk has launched rockets into space, built cars that drive themselves, and reshaped the future of technology. But emotions…

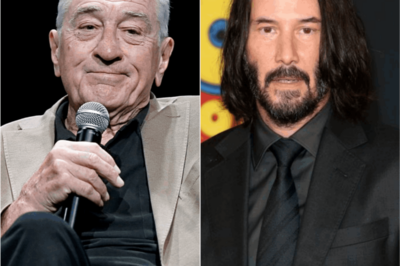

Hand in Hand at the Hudson 💫 Keanu Reeves and Alexandra Grant Turn Heads at “Waiting for Godot” Debut

The entrance that made everyone stop scrolling It wasn’t a red carpet packed with flashing lights. There were no dramatic…

Keanu Reeves and the $20 Million Question: When Values Matter More Than the Spotlight

The headline that made everyone stop scrolling In an industry obsessed with paychecks, box office numbers, and viral moments, one…

URGENT UPDATE 💔 Panic at a Family Gathering as Reports Claim Keanu Reeves Suddenly Collapsed

A shocking moment no one expected Social media froze for a split second—and then exploded. Late last night, a wave…

End of content

No more pages to load