The morning they drove to the camp, the sky over central Germany was a hard, unforgiving blue.

The convoy moved along the muddy road in fits and starts, jeeps kicking up wet earth, the cold air pushing in through canvas flaps that wouldn’t quite stay shut. General George S. Patton, Third Army commander, sat stiffly in the back of his jeep, gloved hands folded over the ivory-handled pistols that hung from his belt like props in an old cavalry painting. The pistols were polished, the boots were polished, the helmet liner was polished. He’d always believed that a soldier should look like a soldier, even at the end of a long war.

He was sixty years old and carried himself like a man who refused to admit it.

Ahead, another jeep bore General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, shoulders hunched under his field jacket, cap pulled low against the wind. Beside him sat Omar Bradley, quiet, watchful, glasses catching the gray light whenever he turned his head. The three of them had seen most of what Europe could throw at a man: the hedgerows of Normandy, the breakout at Saint-Lô, the blood of the Huertgen Forest, the frozen dead of the Ardennes.

And yet Eisenhower had insisted on this trip as if they were raw recruits who needed educating.

Patton didn’t quite understand why.

The liaison officer who’d brought the report rode in the seat beside the jeep driver, clutching a clipboard as though it were a shield. He kept glancing back at Patton like a man who knew he was escorting someone to a place they shouldn’t have to see.

“Remind me,” Patton called over the engine noise, “what’s this place called again?”

“Ohrdruf, sir,” the officer replied, turning his head so his voice carried to the back. “A subcamp of Buchenwald—or so the prisoners say. Our intel’s still sketchy.”

“A prison camp?” Patton asked. His tone was brusque but not unkind, the voice of a man trying to pin an unfamiliar thing into a known category. “We’ve seen prison camps before.”

The officer’s face tightened. “Yes, sir. But this one’s… different.”

Different. Patton turned the word over in his mind like a foreign coin. He had spent thirty years learning how to understand war. He’d studied tactics, read Caesar and Napoleon as other men read novels. He’d memorized the sound of artillery, the way different shells tore the air, the smell of burned gasoline and ruptured flesh. He’d watched men die screaming and men die silently, watched them burn inside tanks and shatter under high explosives. He knew the cost of war, or believed he did.

What could be so different?

Ahead, the road curved around a low rise. As the convoy crested it, the world opened up: a cluster of low wooden barracks, a barbed-wire fence, a gate with a watchtower. A few half-destroyed structures smoked gently in the distance, where artillery had chewed at the edges of the place. The camp sat in a shallow bowl of land, close enough to the nearby town that Patton could see church spires poking above the treeline.

From this vantage point, with the wind working against them, there was nothing especially remarkable about it. If anything, it looked smaller, less imposing than the massive POW enclosures he’d seen elsewhere.

But as the jeeps rolled closer, something else came to meet them.

The smell.

It seeped into the vehicles like a living thing: sweet at first, cloying, then undercut with rot and excrement and something sharp and chemical that stung the back of the throat. It was not the smell of a recent battlefield—Patton knew that odor intimately, knew how death mixed with cordite and explosive and churned soil. This was older. Deeper. Saturated into the very earth.

He saw Eisenhower stiffen in the jeep ahead, saw Bradley lift a handkerchief and press it to his face. The drivers rolled to a stop just outside the gate, engines idling. A cluster of American officers and medical personnel waited for them, some with armbands, some with notebooks. A few wore expressions that were oddly blank, as if they had run out of emotional vocabulary.

An officer stepped forward. “Are you ready, gentlemen?” he asked.

Eisenhower nodded, his jaw set. Bradley said nothing, only removed his glasses briefly to rub at his eyes before replacing them. Patton swung his legs out of the jeep and straightened, boots landing in the mud with a soft slap. The air hit him fully then, the smell wrapping around his head like a physical weight.

He fought the urge to recoil. Thirty years of training, of pride, of carefully constructed legend, held him upright.

“I’ve seen worse,” he muttered, more to himself than anyone else.

He hadn’t. But he didn’t know that yet.

They passed under the gate.

Later, men would talk about that moment as if it were a threshold between worlds. On one side: war as they understood it. Armor and infantry, shells and bullets, movement on maps. On the other: something else, something that made war seem almost comprehensible by comparison.

The first thing that drew Patton’s eyes were the bodies.

They were stacked near a low building, piled with a chilling sort of efficiency. Limbs tangled together, heads thrown back at unnatural angles. Some were naked, some in striped uniforms, some in rags that barely clung to their bones. Ribs stood out like the slats of broken barrels; hipbones jutted like stones under thin, grayish skin. Many had their mouths half open, teeth bared as if in surprise. A few stared up at the sky with eyes that had sunk back into their sockets, as though they had been looking for something that never came.

These were not soldiers. No uniforms he recognized, no bandages, no field dressings. No sign of having been killed in battle. They looked to him like a grotesque parody of firewood, gathered and stacked, waiting to be burned.

He heard someone behind him swear softly, almost reverently, just one word: “Jesus.”

The camp liaison officer cleared his throat. “The SS tried to burn the evidence when they realized we were close,” he said. His voice was careful, professional, clinging to its report-like cadence as if that could keep the horror at arm’s length. “They evacuated most of the prisoners three days ago—death march, by the looks of it. Anyone too weak to walk was shot. They started cremating the corpses, but they ran out of time. That’s what you see here, sir.”

Patton took a step closer to the pile and then stopped. The smell was overwhelming now, coming not just from the decomposing bodies but from the ground itself, from the barracks, from the drains. It clung to everything.

“This can’t be real,” he said abruptly. It slipped out before he could catch it, sounding almost petulant in his own ears. “This has to be…”

“It’s real, sir,” the medical officer beside him said quietly. “And it gets worse.”

Worse.

The word hung in the air.

They moved forward in a small group: Eisenhower, Bradley, Patton, a few aides. An Army photographer followed at a careful distance, his camera hanging against his chest, eyes darting from scene to scene as if trying to decide where to point the lens. War correspondents trailed behind, notebooks ready, faces pale.

They walked past the first row of barracks.

There were no doors on some of them; they’d been thrown open, perhaps by the first American soldiers who’d arrived. Inside, the air was even thicker, heavy with the fumes of unwashed bodies and human waste. Triple-tiered wooden bunks lined the walls, and on each bunk—on each narrow, splintered platform meant for one person—three, sometimes four depressions marked where people had lain.

Patton stepped inside one of the barracks, his boots crunching on straw that might once have served as bedding. Here and there he saw lice crawling, the tiny movements more unnerving than any rat or insect he’d seen in trenches years before.

“This is where they slept,” the medical officer explained. “No heat. Limited water. No sanitation to speak of. Disease was rampant—typhus, dysentery, tuberculosis. The SS didn’t really treat them. If they got too sick, they were simply left to die.”

Patton tried to picture men and women pressed together on these bunks in winter, sharing filth and fever, counting themselves lucky simply because they were still breathing. His imagination, so skilled at conjuring cavalry charges and maneuver warfare, balked.

“Why?” he heard himself ask. “What did these people do?”

The answer came from a thin voice off to the side.

“They did not need to do anything.”

They all turned.

In the far corner of the barracks, half-sitting against the wall, was a man in striped clothing that hung off him like a curtain several sizes too large. His skull was shaved down to fine stubble; his cheeks caved in around high bones. His eyes, sunken but still burning, watched the group with a strange mixture of curiosity and resignation.

A medic knelt beside him, holding a tin cup of water to his lips. The prisoner took slow, careful sips, as if each swallow had to be negotiated with his body.

Patton stepped closer. “What is your name?” he asked.

The prisoner’s lips twitched in something that might once have been a smile. “It does not matter,” he said, his accent thick but his words clear enough. “Names do not matter here.”

“You’re free now,” Patton insisted. The words came out with the instinctive authority of a general making a pronouncement. “We’re Americans. We’ve liberated this camp.”

“Free,” the man repeated, tasting the word like something unfamiliar. His eyes moved to the open doorway, to the slice of pale sky visible beyond. “How can I be free? They killed my wife. My children. My parents. Everyone I loved. I am alive, but I am not free. I will never be free.”

There was no bitterness in his tone. No accusation. Just a flat statement of fact.

Patton, who always had a speech ready, who could quote Scripture and Shakespeare and Napoleon at a moment’s notice, found nothing to say.

Outside, someone called, “General Eisenhower, sir—there’s more you need to see.”

They followed the voice.

The “hospital” was nothing like any medical facility Patton had encountered. It was a dark, low building with narrow windows. Inside, the air was stifling despite the cold day. Forms lay on rough wooden planks—some groaning softly, some silent. A few turned their heads as the group entered, eyes tracking the movement of uniforms. Many did not move at all.

One man stared at the ceiling with unblinking eyes, his mouth slightly open. A medic leaned down, touched his throat, and then shook his head. “Another one gone,” he murmured to himself, more as a notation than a lament.

“How many died here?” Eisenhower asked.

The medical officer hesitated. “We don’t know, sir. Thousands, certainly. The Germans burned most of the records before they fled. We’re piecing together what we can from survivor testimony.”

“And these?” Eisenhower gestured to the rows of barely-living figures.

“Some of them might survive,” the officer replied. “But many won’t. Their bodies are too far gone. We’re trying to feed them, but we have to be careful.”

Patton frowned. “Careful? For God’s sake, give them food. They’re starving.”

“That’s just it, sir,” the officer said, turning to him. “They’ve been starving for so long that their systems can’t handle normal rations. If we give them too much, too fast, it can kill them. It’s called refeeding syndrome. Their bodies have cannibalized their own muscles and organs to stay alive. Their digestive systems… well, they’re barely functioning.”

Patton stared at him. The phrase “cannibalized their own muscles” lodged in his mind like a splinter. “They did this deliberately,” he said slowly, each word falling like a stone. “Starved them on purpose.”

“Yes, sir,” the officer replied. “This was policy. Systematic. Industrialized.”

Industrialized.

It was that word, oddly enough, that made something crack inside Patton. War, in his mind, was a matter of will and courage, of men facing each other with weapons. Even artillery barrages and aerial bombardment, for all their mechanization, still fit into that framework. But this—this was something else. The idea that human beings had sat in offices and drafted rules about how much food to withhold to keep prisoners alive just long enough to extract labor from them, that trains had been scheduled and quotas set and bodies stacked and burned according to plans drafted on clean paper… that was a different kind of horror.

He felt the camp tilting around him, the bunks and bodies and barracks sliding out of the neat categories he’d held in his mind. His stomach rolled.

“I need some air,” he muttered.

He stepped outside, past the hospital building, following the narrow path between structures. The smell followed him; there was no escaping it. After a dozen strides he couldn’t hold it back any longer. He reached the corner of a low structure, braced one hand against the rough wood, and vomited violently into the mud.

His aide, who had been shadowing him, hurried up. “General, are you—”

Patton cut him off with a raised hand, still bent double. “Don’t,” he gasped. “Just… give me a minute.”

Tears sprang to his eyes as his body convulsed. He was not a man who cried easily, and he tried to tell himself it was just the force of the vomiting, the sting of bile. But when the spasms subsided and he straightened, he realized his vision was blurred for another reason.

He wiped his mouth with the back of his glove and stared down at the ground, dotted with his own sick next to the footprints of countless others who had walked this path under very different circumstances.

“I’ve seen men blown apart by artillery,” he said hoarsely, as if needing to remind himself who he was. “I’ve seen them burn alive in tanks. I’ve seen every damned horror war can create.”

He turned his head, eyes falling again on the ragged piles of bodies by the cremation area, on the thin faces watching from the hospital doorway.

“But this…” His voice failed.

For a moment, the legendary Patton—the brash, profane, exuberant warrior who had called war “God’s greatest game”—was just a man in a muddy yard, sick and shaken and suddenly unsure of the world’s shape.

Footsteps approached. Eisenhower came around the corner quietly, as if he’d given Patton time on purpose. The Supreme Commander’s expression was grave, but there was no triumph in it, no sense of “I told you so.” Only a weary sadness.

“George,” Eisenhower said, “I’m going to need you to do something for me.”

Patton straightened automatically, wiping his eyes with a stiff motion. “Anything, Ike.”

“I want every American unit in the area to visit this camp,” Eisenhower said. “Every soldier. I want them to see what they’re fighting against.”

Patton didn’t hesitate. “I agree,” he said.

“And I want the German civilians from the nearby towns brought here,” Eisenhower continued. “Ordruff, Gotha, all of them. I want them marched through this place. I want them to see it. To smell it. To understand what’s been done in their name.”

Patton’s eyes narrowed. “They’ll claim they didn’t know.”

“They’ll claim many things,” Eisenhower replied flatly. “But they knew. Maybe not the details. Maybe not the precise methods. But they knew enough. The camp is right there.” He jerked his head toward the nearby town. “They saw the trains. They saw people go in and not come out. They smelled the smoke. They heard the rumors. They chose not to ask questions.”

“And if they refuse to come?” Patton asked.

“Make them,” Eisenhower said. “At gunpoint, if necessary. This cannot be swept under the rug. It cannot be denied. The world needs to see this.”

Patton looked around once more—the barracks, the bodies, the survivors who looked less alive than some of the dead. When he spoke again, his voice had a new hardness.

“Consider it done,” he said.

That evening, orders went out across Third Army’s spread-out divisions. All personnel in the vicinity of Ohrdruf or similar camps would be required to visit, in organized groups. No exceptions. Units were instructed to bring photographers and note-takers. Officers were reminded that this was not a sightseeing tour but an education.

At the same time, patrols fanned out into the nearby towns, rounding up civilians.

On April 14th, two days after the generals’ visit, the first groups of German civilians were marched up the road to the camp where their compatriots had run it. Some came in their Sunday best, believing it to be some kind of town meeting or administrative requirement. Others shuffled along in work clothes, muttering among themselves, casting suspicious looks at the American soldiers with rifles.

“Why are you doing this?” a middle-aged woman demanded of an interpreter as the gate loomed closer. She clutched her handbag with white knuckles. “What did we do? We are not soldiers. We are just citizens.”

“You’re going to see something,” the American replied. His voice was brittle. “And then you can tell us what you did.”

They were not allowed to stop at the gate. They were not allowed to look away. American officers walked along the line, barking orders—“Eyes forward! Keep moving!”—with a clipped sharpness born not from contempt, but from an almost desperate need to force these people to confront the evidence.

They passed the stacked bodies, the skeletal limbs brushing against their skirts and trousers as the wind shifted. Some gasped. Others put their hands to their mouths. A few tried to avert their faces and were physically turned back by firm hands on their shoulders.

“You could see this camp from your town,” a sergeant from Iowa told a small group, their eyes red-rimmed. “You could smell it when the wind was right. Don’t tell me you didn’t know something was wrong.”

“We… we thought it was a work camp,” a man stammered. He wore a shopkeeper’s apron, his hair carefully combed. “The government said they were criminals. Enemies of the state. We heard rumors, but—”

“Look at them,” the sergeant snapped, grabbing the man’s shoulder and steering him until he stood directly in front of a pile of emaciated corpses. “Do they look like criminals to you? Do they look like people who deserved this?”

The German’s knees nearly buckled. He stared at the bodies as if they might speak.

“Murder,” he whispered finally. “They’re victims of… of murder.”

“Then say it,” the sergeant insisted. His voice trembled not with rage, but with something like a plea. “Say what your government did.”

“My government murdered them,” the man said. Tears streamed down his face, cutting pale channels through the grime. “We… we murdered them.”

Nearby, the mayor of Ohrdruf walked through the camp with an American officer at his elbow. He was a stout man, his overcoat straining over his belly, a Nazi Party pin still on his lapel out of sheer habit. He said nothing as he moved, his jaw clenched, his eyes flickering from scene to scene and then away with mechanical quickness—as if each new image was a blow he could only survive by refusing to look directly at it for more than a second.

When the tour ended, he was placed under house arrest, as was standard for local Nazi officials. That night, he took a rope and ended his own life. The note he left behind was brief and strangely formal.

I did not know the full extent of what was happening, he wrote in a neat hand. But I should have. I should have asked questions. I should have demanded answers. Instead, I looked away because it was easier. I cannot live with that knowledge.

When the news of the suicide reached Patton, his staff watched him carefully. Some half-expected him to express sympathy; suicide, after all, was sometimes an act of despair in soldiers driven beyond their limits.

“Good,” Patton said instead. The word was flat, almost expressionless. “At least he had enough conscience to feel shame. That’s more than most of them seem to have.”

“Sir,” one of his officers began, startled, “isn’t that a bit—”

“Don’t,” Patton snapped, his eyes flashing. “Don’t tell me to feel sorry for them. I’ve seen what they did. What they allowed. Mercy for the guilty is cruelty to the dead.”

It was a side of him they had never quite seen before. The flamboyant bravado remained in his mannerisms—the swagger in his stride, the colorful swearing—but there was a new edge underneath, a coldness that seemed to have very little to do with tactics or military discipline and everything to do with moral judgment.

Meanwhile, American soldiers arrived at the camp in groups. Infantrymen still wearing the dust of their last march, tank crews with oil on their hands, supply clerks who’d never fired a shot in anger. They filed through the gates under the eyes of the skeletal survivors, who watched this strange procession of well-fed, heavily armed men with a mixture of hope and bewilderment.

Private Robert Miller from Kansas came with his platoon on a gray afternoon. He had joined the Army believing, like many farm boys, that it would be an adventure. He’d imagined Europe as a place of picturesque villages and noble struggle. By the time they reached Germany, he had learned that war was mostly fear and exhaustion and mud.

But nothing had prepared him for this.

He walked past the bodies without really understanding what he was seeing. His mind kept trying to categorize: sick, injured, wounded. It took several moments for the lack of movement, the unnatural angles, to register.

“Oh God,” someone behind him choked out. “They’re all dead.”

Miller’s hand went automatically to the small notebook he kept in his breast pocket. That night, under the dim light of a candle in a commandeered farmhouse, he wrote:

I thought I understood what we were fighting for. Freedom, democracy, defeating tyranny. We’ve all said those words. But today I saw something that made those words real in a way I never wanted to understand. This isn’t war. This is evil. Pure evil. And I’m proud to be fighting against it.

Sergeant James Cooper, who’d been in the Army long enough to have learned how to keep his emotions under layers of sarcasm and bravado, lasted until he reached the cremation area. The sight of bodies half burned, charred limbs protruding from piles of ash, the unmistakable shape of a child’s skull among them—that was too much. He stumbled away, leaned against the outer wall of a barracks, and vomited until there was nothing left.

When he straightened up, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, he saw his squad watching him. Some looked scared; others seemed strangely relieved, as if his reaction had given them permission for their own horror.

“Listen up,” Cooper said, his voice still rough. “Anyone who surrenders to us from now on, you treat them right. You follow the rules. You hear me? We’re soldiers, not like them.”

He jerked his head toward the camp behind him.

“But don’t any of you ever forget what we saw here today. Don’t let anyone, ever, tell you we were wrong to fight this war.”

Many who passed through Ohrdruf in those days would carry the images for the rest of their lives. Some would talk about it to their children and grandchildren, voices breaking as they tried to find language for something that resisted description. Others would lock it away, refusing, even decades later, to unseal that part of their memory.

“I saw combat,” a veteran would say in an interview in the 1980s, his hands trembling as he spoke. “I saw my friends die. But the camp—that was worse than any battle. Battles…” He shrugged helplessly. “Battles make sense in a sick way. What happened there makes no sense at all.”

While the soldiers walked the camp paths, Eisenhower’s decision to bring in photographers and war correspondents began to bear fruit. Cameras clicked constantly, capturing everything—the piles of corpses, the faces of survivors, the expressions on American soldiers’ faces as they absorbed the scene. Journalists scribbled in notebooks, trying to keep up with the flood of details.

The photos went out in dispatches, traveled with the speed of wires and planes across the Atlantic. Editors in New York and London stared at them in disbelief. Some shook their heads, thinking they must be some sort of elaborate trick.

“Too graphic,” one editor said, pushing aside a particularly gruesome image of a mass grave. “We can’t print that. People will be sick.”

“But sir,” the young journalist argued, “that’s the point. People should be sick. They need to see this.”

In the end, compromises were made. Some of the worst images were held back. Others—still horrific, but marginally less so—made the front pages. Headlines screamed words like “NAZI HORROR CAMP REVEALED” and “ATROCITIES IN GERMANY STUN LIBERATORS.” The name of Ohrdruf, once just a small German town, became synonymous with something much larger in the minds of readers.

Not everyone believed what they saw.

“It’s propaganda,” some skeptics said in barbershops and diners. “It has to be. No civilized nation would do something like that. Those photos are staged.”

But Eisenhower, Patton, and Bradley all issued statements. They described, in measured but unflinching terms, what they had seen. They made it clear that if anything, the photographs understated the reality. Congressional delegations were organized, senators and representatives flown to Europe to tour the camps themselves. They returned shaken, their reports carrying weight to those who distrusted journalists.

Public opinion, which had already solidified firmly against Nazi Germany, hardened further. Any lingering doubts about whether the war had been necessary evaporated. The question “Why are we fighting?” now had an answer that could be pointed to in black-and-white photographs: because of this.

In Patton, something more subtle and more personal shifted.

Before Ohrdruf, he had often spoken of war as a spectacle, as a proving ground for courage and leadership. He loved the maneuver, the clash, the contest. He believed in the “honorable enemy”—a worthy opponent against whom a man could test himself and, in defeating, gain a kind of reflected glory. He had praised German soldiers for their discipline and skill, had talked with grudging respect about the Wehrmacht’s professionalism.

After Ohrdruf, the word “honorable” died on his lips more than once.

“I don’t want to hear about the ‘good German soldier’ anymore,” he told his staff one evening, pacing the room with a restlessness they’d come to recognize. “I don’t want to hear about their damnable military tradition or what fine comrades they were in the trenches of the last war.”

He stopped by the window, looking out at the night, the glow of fires on the horizon where other battles still raged.

“They knew,” he said. “They were part of a system that did this. You cannot put on a uniform in that army and claim you didn’t know something was rotten at the core.”

His staff exchanged glances. Some agreed wholeheartedly; others, who’d been dealing with Wehrmacht officers and POWs and had seen moments of decency and humanity among them, felt unease. But no one contradicted him. Not then.

When German units surrendered in the weeks that followed, officers sometimes attempted to do so with the old forms of military ceremony. They tried to preserve a shred of dignity: marching their men in formation, presenting their weapons with precise movements, requesting the right to keep their sidearms as a symbolic gesture.

Patton refused.

“You lost the right to honor when you served that regime,” he told one German colonel who, even in defeat, held himself with stiff, aristocratic pride. “You will surrender as criminals, not as soldiers.”

Still, despite his emotional transformation, Patton did not let his outrage turn into unlawful cruelty. His orders regarding prisoners of war remained technically within the scope of the Geneva Convention. They were fed, housed, and guarded according to regulations. But the easy camaraderie he had sometimes shown toward captured officers earlier in the campaign—the shared drinks, the talk of tactics and campaigns—evaporated. The gulf between “us” and “them” had become unbridgeable in his mind.

In May 1945, the war in Europe ended. The guns fell silent. Cities lay in ruins; millions were displaced, wandering roads with what possessions they could carry; whole nations had to figure out how to exist again without constant fear.

During the victory celebration, when champagne corks popped and flags flew and bands played in halls that still smelled faintly of smoke and dust, Eisenhower tugged Patton aside.

“George,” he said, “I’m recommending you for a new assignment.”

Patton, who was already thinking about redeploying men, about perhaps being sent to the Pacific to fight the Japanese, raised an eyebrow. “Oh?”

“Military Governor of Bavaria,” Eisenhower said. “You’ll oversee the occupation, establish order, work with the local civilian authorities.”

The words “work with” hit Patton like a slap.

“You want me to work with Germans?” he demanded. “After what we saw?”

“Someone has to,” Eisenhower said patiently. “We can’t leave Germany in chaos. The Soviets are already pushing their influence. We need to stabilize our zone. And you, whether you like it or not, are one of our best administrators. You get things done.”

Patton’s jaw clenched. He thought of the mayor of Ohrdruf swinging from a rope. He thought of the shopkeeper forced to say We murdered them. He thought of the nameless prisoner in the barracks who had said, I will never be free.

“I don’t want to rebuild them,” he said quietly. “I want them punished.”

“They will be punished,” Eisenhower replied. “There will be trials. There will be denazification. But we also have to think beyond punishment. If we simply crush them and walk away, we’ll sow the seeds of the next war. We need a Germany that is different from the one that gave us Hitler.”

In the end, Patton accepted. He was a soldier, and orders were orders. But the assignment sat in him like a stone.

As Military Governor, he found himself mediating between competing demands—Washington’s insistence on swift denazification, the practical necessity of using former Nazi Party members who were the only ones with administrative experience, the immediate needs of millions of civilians just trying to survive in a shattered land. He sat in offices with German officials who assured him that they had never really agreed with Hitler, that they had only joined the Party to keep their jobs, that they had known very little about “those things.”

He believed some of them. He suspected most. He trusted almost none.

“You’re too harsh,” some of his American colleagues complained. “You can’t treat everyone as equally guilty. We need administrators, teachers, policemen. If we purge every last one who ever wore a swastika, there’ll be nobody left to run anything.”

“They elected that regime,” Patton argued, anger simmering in his gut. “They supported it. They looked the other way when the trains rolled past. How am I supposed to sit at a table with them and pretend we’re partners now?”

“Because we need them,” Eisenhower said when he eventually had to intervene. “I know it’s not fair. I know it’s not just. But reality doesn’t care about our feelings, George. We can’t rebuild without some of them.”

Patton never entirely reconciled himself to this. The contradiction gnawed at him: he had spent his life training to defeat enemies, not to make compromises with them after victory. Ohrdruf had sharpened his sense of moral clarity, but the world around him required moral ambiguity.

Within months, Eisenhower relieved him of his position as Military Governor. Officially the reasons were a mixture of political considerations, controversial public statements Patton had made, and Washington’s discomfort with his outspokenness. Unofficially, many suspected that his inability to separate the German people from the Nazi regime, his unwillingness to soften his stance, had made him unsuited to the delicate work of occupation.

“You’re too emotionally involved,” Eisenhower told him in a frank moment. “You can’t see where the gray begins.”

Patton did not argue. He simply nodded, understanding that the war he had been built for was over, and the new world belonged to men more comfortable with compromise.

The soldiers who had walked through Ohrdruf, meanwhile, went home one by one. They returned to Kansas farms and Chicago factories and New York streets. They married, raised children, worked jobs. The war receded, as wars do, becoming a series of stories told around kitchen tables or not told at all.

Some spoke openly of battles—of the terror of artillery barrages, the crack of rifle fire, the strange stillness after an attack. They spoke of foxholes and chow lines, of comradeship and loss. When the subject of the camps came up, though, many fell silent.

“I can tell you about the Bulge,” one veteran told his teenage grandson decades later. “I can tell you about crossing the Rhine. But what we saw in that camp…” He shook his head. “That’s not a story. That’s something else.”

Others did speak. Sometimes the words tumbled out unexpectedly, prompted by a photograph or a TV documentary or a careless remark about how “it couldn’t really have been as bad as they say.”

“It was worse,” one man insisted in a televised interview in the 1990s. His voice shook, but his gaze was firm. “You can’t smell a photograph. You can’t feel the air in there. You can’t hear the way people breathed, the way their bones creaked when they moved.”

People asked, as the decades passed and wars came and went, “Was it worth it? All those lives, all that destruction. Was it worth it?”

The veteran thought about Ohrdruf, about the faces of the survivors, about the rows of dead. “Yes,” he said finally. “Whatever it cost, it was worth it to stop that. If we hadn’t, what would the world be?”

Back in December 1945, with snow on the ground in Germany and Christmas decorations appearing in towns that were slowly stitching themselves back together, Patton’s own story drew to an abrupt, cruel close.

It did not end on a battlefield, as many had assumed it would. Instead, it ended on the side of a road near Mannheim, in a car accident—violent, sudden, absurdly mundane after all he had survived. A broken neck left him paralyzed from the shoulders down. He was taken to a hospital in Heidelberg, the great general reduced to a man who could barely move, trapped in a bed with white sheets.

He had time to think, perhaps more time than he wanted.

A chaplain visited him often. They talked about many things: Patton’s career, his belief in destiny, his complicated relationship with God. They spoke of his ancestors, of the battles he’d studied and the battles he’d fought.

“I need to tell you something about the camps,” Patton said one day, his voice raspier than before.

“You don’t have to, sir,” the chaplain replied gently. He had heard fragments already, from other soldiers. “You’ve been through enough.”

“I do,” Patton insisted. His eyes, still sharp despite the pain, fixed on the chaplain’s face. “All my life, I thought war was… noble, in some way. A test of courage and skill. The crucible where men prove themselves. I loved it.” He gave a twisted half-smile. “God help me, I loved it.”

The chaplain said nothing, sensing that the confession was not yet complete.

“But the camps,” Patton continued. “Ohrdruf. Buchenwald. The things we found. That wasn’t war. That was something else entirely.” He paused, searching for words. For once in his life, rhetoric failed him. “I don’t have a name for it,” he admitted.

“Evil,” the chaplain suggested quietly.

Patton let the word hang in the air for a moment, tasting it as the nameless prisoner had once tasted “free.”

“Evil,” he agreed. “Pure evil. And I’m glad I fought against it. Whatever else I did, whatever mistakes I made, at least I fought against that.”

Two days later, he was gone.

At Patton’s funeral, Eisenhower spoke of him as “brilliant, difficult, courageous to the point of recklessness.” He talked about his exploits in North Africa, Sicily, France. He talked about the speed with which Patton’s Third Army had driven across Europe. But he also mentioned something else.

“After he visited Ohrdruf,” Eisenhower said, “George understood, in a way few of us did, what we were really fighting for. Not just for territory or even for nations, but against something that had no place in any civilized world.”

Back in April, when he’d first walked out of Ohrdruf, Patton had said words that would be repeated, misremembered, and argued over for years.

“They’re not Germans anymore,” he’d told an aide, staring back at the camp as if it were a wound in the earth. “They’re not soldiers. They’re something else. Something that needs to be destroyed completely.”

He hadn’t meant the people as a race or a nation—whatever his other flaws, he was not calling for the extermination of a people. He had meant the system, the ideology, the machinery of dehumanization that had turned names into numbers, men and women into labor units, bodies into ash.

He had glimpsed, in that reeking compound, a darkness that went beyond the battlefield. And it had changed him.

April 12th, 1945: George S. Patton walked through the gates of Ohrdruf as a general who believed that war, for all its horror, held a kind of glory. By the time he walked out, some part of that belief had died.

What replaced it was not pacifism; he never stopped believing that war was sometimes necessary. But now, when he thought of necessity, he saw not gallant charges or brilliantly executed maneuvers. He saw skeletal figures in striped uniforms. He saw bodies stacked like cordwood. He saw the word industrialized applied not to production lines for cars or tractors, but to murder.

He saw, in short, what they had been fighting against all along, stripped of all its banners and rhetoric and uniforms.

The world changed with him, in slow, uneven ways. The camps were liberated, one after another. Their names—Ohrdruf, Buchenwald, Dachau, Auschwitz—entered the language as shorthand for something almost unspeakable. The photographs and the testimonies piled up. Trials were held in Nuremberg, where men who had signed the orders and drafted the laws were forced to listen as their deeds were laid out in detail.

Over time, as the last liberators and survivors aged and died, memory threatened to blur into history. But the images remained. The documents remained. The physical sites—preserved as memorials, with barbed wire and barracks left standing—remained. Schoolchildren walked through the same gates the generals had walked through, now with guides and audio tours instead of guards and guns.

They wrinkled their noses at the faint lingering smell of old wood and damp stone, at the imagined echo of that earlier stench. They saw photographs of Patton and Eisenhower standing in the courtyard, their faces grave. They read his words: Remember what you saw here. Never let anyone deny this happened.

Eighty years after the war, the world still tells the story.

It tells of a spring morning in 1945 when three generals and a handful of officers and reporters passed under a gate and came face to face with something that would change them. It tells of a proud man brought to his knees by the sight of what had been done behind fences just a few miles from ordinary towns. It tells of soldiers who thought they were fighting for territory or flags and discovered they were fighting for something much more basic: the right of human beings not to be treated as fuel.

There are people, even now, who claim the camps were exaggerated, or that they did not exist as described. But the record remains: photographs, films, orders, letters, survivors’ testimonies, liberators’ diaries. And among those records, somewhere, are the footprints in the mud of a general who loved war, standing beside the marks left by men who had been starved nearly to death.

In that patch of ground at Ohrdruf, the myths that had comforted him about the nobility of war were stripped away. What was left was harsher, but truer: war is not glorious, but sometimes it is the only way to stop something worse.

That day, as he stood with bile still burning his throat and tears he wouldn’t admit in his eyes, George S. Patton understood, more clearly than ever before, why his army had come to Europe. Not for glory. Not for conquest. But to break apart a system that could produce a place like this.

And he would spend the rest of his short remaining life making sure the world remembered what he had seen, so that, as long as men still told the story of the war, they would know what lay behind the abstract word evil.

Not an idea, but a place—with gates and barbed wire, barracks and crematoria, bodies stacked like wood, and a smell that no one who walked through it could ever fully wash from their memory.

News

“‘Clean This Properly!’ the CEO Roared 😠 — Completely Unaware That the Man in Tattered Clothes Was Keanu Reeves in Disguise, Seconds Before a Corporate Meltdown, a Hidden Takeover Plot, and a Twist So Ruthless and Deliciously Cinematic Erupted That Executives Nearly Fainted From Shock 🏢🔥” Witnesses swear the CEO’s smug bark curdled into sheer panic when the ‘janitor’ lifted his head, triggering whispers of secret audits, undercover missions, and a karmic ambush years in the making

The Man Behind the Rags: A Shocking Revelation In the bustling heart of the city, where ambition thrived and dreams…

“LUXURY STORE ERUPTION 💎 Arrogant Socialite Hurls a Snide Insult at Sandra Bullock—Only for Fictional Keanu Reeves to Deliver a Breathtaking, Ice-Cold Reaction That Stops the Entire Boutique in Its Designer-Heeled Tracks 😱” — In this sparkling fictional meltdown, diamonds aren’t the only things cutting deep as Keanu’s silent glare slices through the tension, leaving the smug woman trembling while stunned shoppers cling to their pearls and gasp for emotional oxygen👇

The Jewel of Deceit In the heart of Beverly Hills, where glamour and wealth intertwine, a lavish jewelry store stood…

Keanu Reeves’ Secret Letter to Diane Keaton — The Quiet Confession That Sat Unread for Years and Rewrote a Hollywood Myth 💌 The narrator leans in with a sly hush as envelopes, dates, and a single sentence ignite whispers of restraint, timing, and a truth never meant for headlines, suggesting the real scandal wasn’t romance but the discipline to let love stay unclaimed until the moment passed forever

The Line Drawn: A Story of Missed Connections In the dazzling realm of Hollywood, where the glow of fame often…

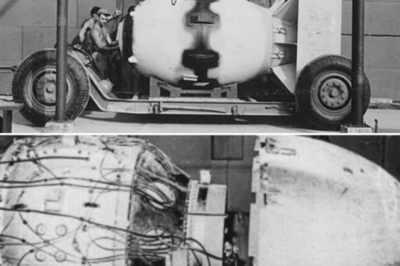

HOW FAT MAN WORKS ? | Nuclear Bomb ON Nagasaki | WORLD’S BIGGEST NUCLEAR BOMB

On August 6th, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The bomb was…

Why This ‘Obsolete’ British Rifle Made Rommel Change Tactics Uncategorized thaokok · 21/12/

April 1941, the Libyan desert outside Tobrook, Owen RML watched his panzas advance toward the Australian defensive perimeter, confident his…

“Inside the Ocean Titanic Recovered: After 80 Years, the Titanic Reassembled Piece by Piece — What They Found Will Shock You!” After 80 years submerged, the Titanic has been fully recovered and reassembled piece by piece, and what experts discovered during the process is far more shocking than anyone could have imagined. Hidden inside the wreckage were cryptic messages, unexplained artifacts, and eerie signs of the ship’s final moments. The Titanic’s restoration reveals a deeper, darker story than we’ve ever been told. The truth about the ship’s fate will haunt you forever

Echoes from the Abyss: The Resurrection of Titanic In the depths of the Atlantic, where shadows linger and whispers of…

End of content

No more pages to load