Mel Gibson did not get into The Passion of the Christ out of artistic ambition.

He came out of desperation.That dark night in 1999, alone and defeated, he knelt down and truly prayed for the first time in decades.

It was not a learned prayer, but the cry of a man who had tried everything and had failed at what was essential.

From that moment on, something changed with an inner violence that he himself described as sudden and terrifying.

For the next five years, Gibson became obsessed with the last hours of Jesus Christ.

He studied the gospels like an academic, read Roman history, talked to philosophers, and delved into the mystical visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich.

The more I investigated, the more convinced I became that this story could not be told in a convenient or commercial way.

I had to be brutally honest.

When he took his idea to Hollywood, the answer was unanimous: no.

A film about the crucifixion, spoken in Aramaic and Latin, without stars and with explicit violence was, according to Disney and Warner, professional suicide.

But Gibson was no longer seeking approval.

He invested $30 million of his own money, without studies, without insurance, and without a safety net.

If he failed, he would lose everything.

And yet it moved forward.

To give authenticity to the project, he went to a small Catholic church in Los Angeles, where he met Father William Fulco, a Jesuit priest and linguist.

Fulco warned that ancient languages had a spiritual weight that could be unsettling.

But he also sensed that Gibson wasn’t making “another biblical movie.”

Something deeper was at stake.

The casting process was as strange as the project.

Gibson rejected top-tier stars.

He wasn’t looking for fame, he was looking for souls.

The auditions turned into conversations about faith, suffering, and sacrifice.

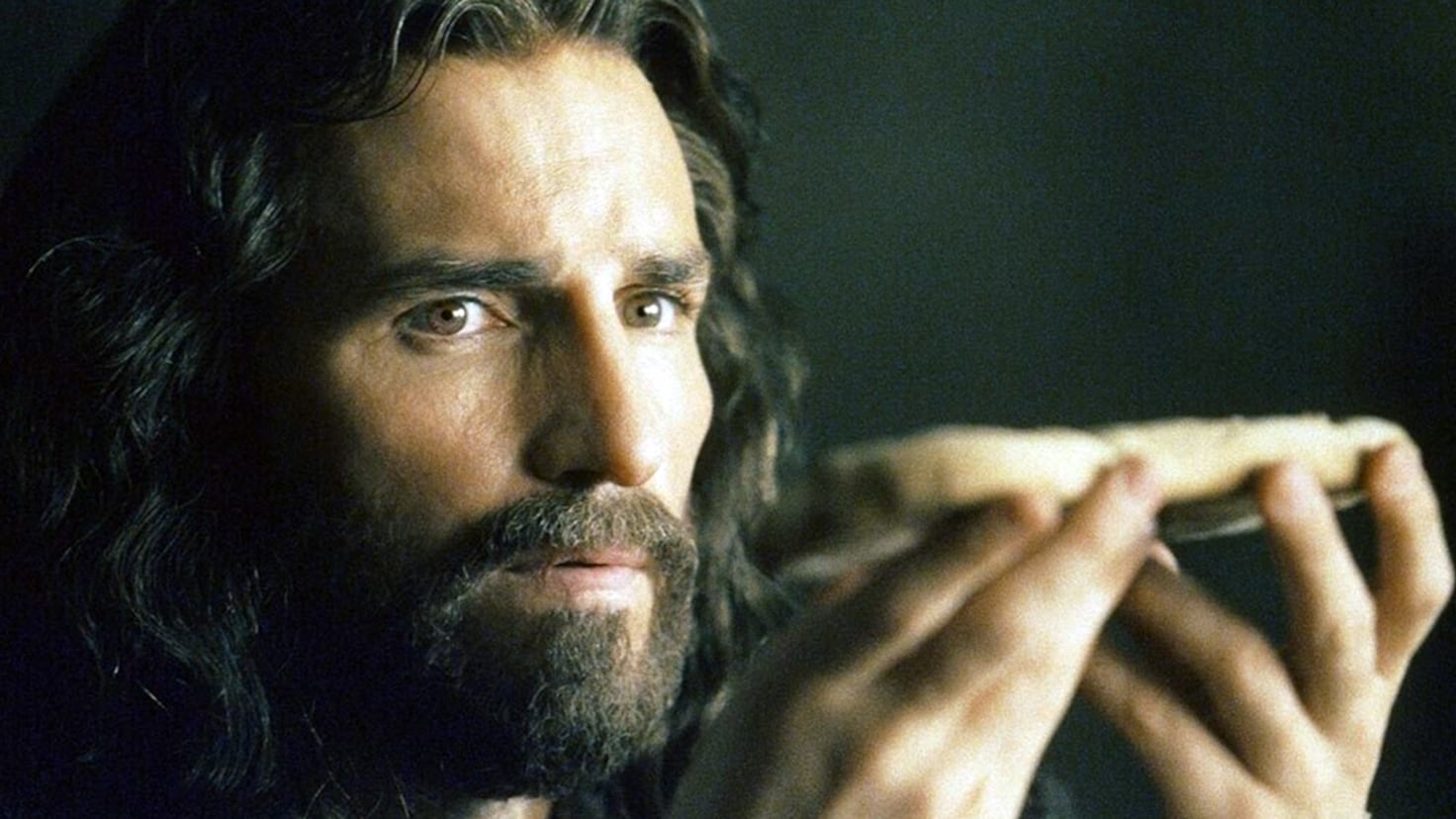

When Jim Caviezel appeared, 33 years old and with the initials JC, everything seemed to align in a disturbing way.

Gibson was blunt: accepting the role could cost him his career.

Caviezel responded with a phrase that sealed his fate: “We all must carry our cross.”

Matera, Italy, was transformed into Jerusalem.

A city carved into the rock, suspended between time and eternity.

Filming began there, and with it, the inexplicable events.

On November 17, 2003, the sky darkened without any weather warning.

Violent winds arose from nowhere.

A lightning bolt struck Gian Michelini, assistant director, leaving visible burns.

The silence that followed was the most disturbing thing: no wind, no birds, no voices.

Just an absolute void.

Minutes later, another lightning bolt struck Caviezel.

The actor claimed to have felt it before it happened.

Witnesses said they saw a glow around his head.

Doctors were never able to fully explain the physical consequences he suffered for years, including heart problems that required subsequent surgeries.

The phenomena continued.

Sudden storms during flagellation scenes.

Teams that only failed at specific times.

Sound engineers capturing voices when no one was speaking.

Actors and technicians feeling invisible presences.

A makeup artist left the set without explanation after weeks of anguish.

Meanwhile, Caviezel’s physical suffering outpaced any planning.

A mistake with the Roman whip opened his back with a wound of more than 30 centimeters.

The blow from a 68-kilo beam pierced his tongue.He filmed crucifixion scenes for hours in extreme cold, developing hypothermia and pneumonia.

The lightning strike left lasting effects for a decade.

Caviezel would later speak of a spiritual experience so intense that returning to consciousness was painful.

When the film was released in 2004, Hollywood expected a disaster.

The opposite happened.

Entire churches organized bus trips.

People were crying silently during the credits.

Prayer circles formed in the lobbies.

It grossed $23 million on its first day.

The first weekend, 84 million.

It became the highest-grossing independent film in history.

The reaction was violent and polarized.

Some called it a spiritual experience.

Others, dangerous propaganda.

Organizations denounced possible social consequences.Critics spoke of extreme violence.

But no one left indifferent.

Even Roger Ebert admitted that the film conveyed the suffering of Christ like never before.

The price was high.

Caviezel left his mark on Hollywood.

Gibson went from respected genius to pariah after subsequent scandals.

However, something had changed forever in those who were there.

Actors who became.

Technicians who regained their faith.

People who, twenty years later, refuse to talk about what they experienced.

Today, when Mel Gibson is asked about those events, he only responds with one sentence: “To this day, nobody can explain it.”

Perhaps because not everything is meant to be understood.

Some experiences do not seek explanation, but transformation.

And The Passion of the Christ was not just a movie.

It was a breaking point where art, pain, and the sacred collided head-on.

News

Elon Musk Lands $13.5M Netflix Deal for Explosive 7-Episode Docuseries on His Rise to Power

In a move that’s already sending ripples across the tech and entertainment worlds, billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk has reportedly signed…

“MUSIC OF QUARKS”: Elon Musk Unveils Technology That Turns Particles Into Sound – And The First Song Is So Beautiful It Will Amaze Everyone!

In a revelation that has shaken the scientific world to its core, Elon Musk has once again stepped beyond the limits…

The Promise He Never Knew He’d Make

Elon Musk has launched rockets into space, built cars that drive themselves, and reshaped the future of technology. But emotions…

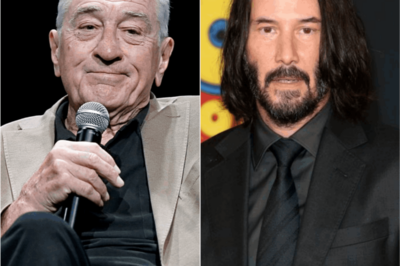

Hand in Hand at the Hudson 💫 Keanu Reeves and Alexandra Grant Turn Heads at “Waiting for Godot” Debut

The entrance that made everyone stop scrolling It wasn’t a red carpet packed with flashing lights. There were no dramatic…

Keanu Reeves and the $20 Million Question: When Values Matter More Than the Spotlight

The headline that made everyone stop scrolling In an industry obsessed with paychecks, box office numbers, and viral moments, one…

URGENT UPDATE 💔 Panic at a Family Gathering as Reports Claim Keanu Reeves Suddenly Collapsed

A shocking moment no one expected Social media froze for a split second—and then exploded. Late last night, a wave…

End of content

No more pages to load