April 1945, a muddy prisoner camp somewhere near the rine. Rows of German women stood shivering in the cold morning air. Their coats were buttoned tight. Their hands were numb. Their hearts were pounding. They had survived bombs falling from the sky. They had survived running from burning cities. They had survived being captured by enemy soldiers.

But now an American officer walked slowly down the line. He stopped. He looked at them and then he gave an order that made their blood turn to ice. Open your coat. Three words. That was all. Some women froze. Some grabbed their coats tighter. One young woman felt her legs go weak. She thought she might collapse right there in the mud. They knew what this meant.

They had been warned about this moment for years. Every poster, every radio broadcast, every whispered story had prepared them for this. This was it. the moment they feared most. But here is the strange part. What happened next was not what any of them expected. Not even close. In fact, it was the complete opposite.

And when they finally understood what was really happening, some of them started to cry. But not from pain, not from shame, from something they never thought they would feel again. What did that order really mean? What did the Americans actually do? and why did it change everything these women believed? Stay with me until the end because this true World War II story will surprise you.

If you love real history stories that are not in the textbooks, hit that subscribe button right now. Click the like button to support this channel and watch the full story poem because the ending will shock you. Let’s begin. They were never supposed to be there. Not in uniform, not near the front, not in the path of collapse.

But by 1945, thousands of German women were exactly where the Nazi command had once promised they would never be, inside the machinery of total war. Hanalora Voit was 22 when she was assigned to a vermarked signals unit. She had trained as a radio operator in a clean school building in Bavaria.

She wore a gray auxiliary uniform. She typed coded messages. She plotted coordinates. She never fired a gun. She was not a soldier, but she moved with soldiers. And when the soldiers retreated, so did she. Renata Kesler had been a cler in a supply depot near the Rine. Her job was simple.

Track inventory, file reports, stamp documents. She worked in a basement office lit by a single bulb. The work was boring, safe, forgettable. until February 1945 when the American advance shattered the front lines. The depot was abandoned in hours. Renate grabbed her coat and followed the convoy west. There was no plan.

There was only movement. Analisa Faulk was 19, a nurse’s aid. She had volunteered because it seemed noble. She had imagined tending to wounded heroes in clean hospitals behind secure lines. Instead, she found herself in a field station that moved every 3 days. Wounded men screamed on tables made of doors.

There was never enough morphine, never enough bandages. And when the shelling got close, they packed the trucks and ran. Voltrad Linderman drove one of those trucks. She was 28, older than most, stronger. She didn’t talk much. She just drove through mud, through smoke, through roads clogged with refugees and deserters.

She kept her hands on the wheel and her eyes forward. She had learned not to look at the faces. The numbers were staggering. By the final year of the war, more than 500,000 German women served in auxiliary roles across the Vemar, Luftvafa, and SS. They were radio assistants, typists, switchboard operators, drivers, cooks, nurses, and clerks.

Most were between 18 and 25. Most had never seen combat. Most believed they would be kept far from danger. They were wrong. Caught in the flood. When the Third Reich began to collapse in the spring of 1945, military order dissolved into chaos. Entire divisions retreated without coordination. Supply lines vanished.

Commands were ignored or never received. And the women, those clarks, those drivers, those radio operators were swept along like debris in a flood. Alfreda Roth had been stationed at a communications hub in the Ruer Valley. When American forces encircled the region, the officers fled first. The women were told to wait for transport.

The transport never came, so they walked 30 km in 2 days. No food, no map. Alfreda’s boots tore open her heels. She wrapped them in cloth torn from her undershirt. The cloth turned red. She kept walking. Troutworth wasn’t even military. She had worked as a civilian translator at a local headquarters. When the staff evacuated, she begged to go with them.

She had a husband in a P camp somewhere in France. She needed to survive long enough to find him. They let her climb into the back of a truck. No one checked her papers. No one cared. Surrender came in pieces. Some women were captured at roadblocks, others during mass surreners. Some were found hiding in barns, basement or abandoned schools.

Hanalor Voit’s unit was stopped by American troops on a country road outside castle. The soldiers were young, tired. They pointed rifles and shouted in English. Hanalor raised her hands. So did the 12 other women in the back of the truck. One of the American soldiers looked confused. He called for his sergeant.

“What do we do with them?” he asked. The sergeant shrugged. Same as the men processed them, moved them to the cage. The cage, that was the word they used, prisoner cage. Hanalor’s stomach dropped. They were not prepared. None of these women had been trained for captivity. There were no protocols, no instructions, no reassurances.

They had been taught to type, to bandage, to drive, to follow orders. But no one had taught them what to do when the war ended and they became the enemy. Renard Kesler would later write in her memoir, “We did not think of ourselves as soldiers. We thought of ourselves as workers, as helpers.

We believed that because we had not fought, we would not be punished. We were mistaken. In the first weeks of May 1945, Allied forces processed tens of thousands of German prisoners daily. The camps swelled. Tents were erected in muddy fields. Barbed wire surrounded empty pastures. The women were separated from the men and moved into smaller compounds.

There were no beds, no stoves, just canvas, dirt, and cold. And there, in those camps, fear began to grow. Not from what was happening, but from what they imagined might happen next. Fear does not need evidence to grow. It only needs silence. And inside the prisoner camp, silence was everywhere.

The women did not know what would happen to them. They had no information, no schedule, no answers. They only had rumors and memories of warnings they had been hearing for years. The propaganda had started long before the war ended. From 1943 onward, as the tide turned against Germany, Nazi officials began preparing the population for the possibility of occupation.

But they did not prepare them with truth. They prepared them with terror. Ysef Gerbles, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, understood one thing perfectly. Fear of the enemy kept people loyal. And so he fed that fear deliberately constantly ruthlessly. Posters appeared in train stations and town squares.

They showed brutal caricaturures of Allied soldiers. Beneath them, warnings were printed in bold letters. Protect your women. Protect your honor. The enemy shows no mercy. Radio broadcasts told stories of occupied villages in the east. Stories of violence. Stories of women dragged from their homes.

stories designed not to inform but to horrify. Hanalor Voit remembered listening to one such broadcast in early 1944. She was still in training then. The voice on the radio was calm, clinical, but the words made her skin crawl. In the Soviet zones, German women are treated as spoils of war.

There is no law, no protection, no mercy. She had glanced around the room. Every woman there had gone pale. The message was clear. Surrender means suffering. It was not just propaganda. It was poison. And it worked. By the time Germany collapsed, an entire generation of women had internalized a single belief.

Capture by enemy forces, especially by American or Soviet troops meant humiliation, assault, or worse. Renardi Kesler later wrote, “We were more afraid of the enemy than we were of our own bombs. At least bombs were random. But soldiers, soldiers chose their victims. The whispers in the camps made it worse.

Inside the prisoner compounds, information moved in fragments, a sentence overheard. A story passed from one woman to another in the dark. No one knew what was true. But everyone listened. Anala Fal heard a story her second night in the camp. An older woman, someone who claimed to have been captured weeks earlier, spoke in a low voice near the tent flap.

They take you out at night, she whispered. One at a time. They don’t tell you where. You just don’t come back the same. Analisa felt her chest tighten. She wanted to ask what that meant, but she was too afraid of the answer. Alfreda Roth heard a different version. In her section of the camp, the rumor was that the Americans were separating women for special interrogations.

No one knew what that meant either, but the word special carried weight. It sounded deliberate, targeted, personal. Troutworth tried not to listen. She sat in the corner of the tent with her knees pulled to her chest, her coat wrapped tight. She thought about her husband. She thought about home.

She tried to block out the voices, but at night in the cold, with nothing but canvas between her and the unknown, even she could not ignore the fear. The numbers reveal the scale. By May 1945, more than 80,000 German women were held in Allied prisoner camps across Western Europe. Most were concentrated in makeshift facilities in France, Belgium, and occupied Germany.

The camps were overcrowded. Resources were scarce. Medical supplies were limited. But the greatest shortage was not food or blankets. It was information. The women were not told how long they would be held. They were not told what would happen next. They were not told anything, and into that vacuum fear poured like flood water, while Trout Linderman tried to keep order.

She had always been the practical one, the one who didn’t panic, the one who kept driving when others froze, but even she felt it. The weight of waiting, the dread of the unknown. One evening she gathered a small group of women in her tent. She spoke quietly but firmly. “Listen to me,” she said.

Most of what you’re hearing is nonsense, rumors. We have to stay calm. One of the younger women looked at her with wide eyes. But what if it’s true? What if they they haven’t? Walrod interrupted. Not yet. So until something actually happens, we do not fall apart. It was a thin thread of logic, but it was all she had to offer.

The sensory memory stayed with them. Years later, many of these women would describe the camps in the same way. Not by what they saw, but by what they felt. The cold that never left. The damp wool smell of too many bodies in too small a space. The taste of fear, metallic and sharp at the back of the throat.

Hannalor Voit remembered the sound most clearly. The low hum of whispered conversations that never stopped day and night. a constant murmur of anxiety. It was like being inside a beehive, she later wrote, except the bees were all waiting to be crushed. And then one morning, the waiting ended. Guards moved through the camp before dawn.

They shouted orders in English. Women were told to line up outside immediately. No delays, no explanations. Anala’s hands shook as she buttoned her coat. Renata’s breath came fast and shallow. Troud closed her eyes and whispered a prayer she hadn’t said since childhood. While Troud stood near the front of the line, her face was stone, but inside her heart hammered.

Hannal clenched her fists inside her pockets. She thought about her family. She thought about the radio she used to operate. She thought about everything she had survived to get here. and she wondered if this was the moment all the warnings had been leading to, the moment they had been taught to fear most.

The yard was not large, maybe 50 m across, bare dirt, patches of mud where the rain had pulled, a single wire fence on three sides. It was barely dawn, the sky was gray. The air smelled of wet canvas and woodsm smoke from the guard station. The women stood in uneven rows, shouldertosh shoulder.

Some had buttoned their coats wrong in the rush. Others had no coats at all, just thin wool jackets issued days earlier. There were no chairs, no shelter, just the open ground and the cold. Hannah Voit counted the women in her line. 23 She counted them twice to keep her mind busy, to stop herself from thinking about why they were there.

Behind her, someone coughed. a wet rattling sound, the kind that came from sleeping on frozen ground for too many nights. No one had explained the order. The guards had simply shouted, “Rouse, rouse, out, out.” The women had stumbled from their tents into the pale morning light. They formed lines because that was what you did when soldiers shouted. “You obeyed.

You did not ask questions. But now, standing in the silence, the questions came anyway.” Analia Fal whispered to the woman beside her. “What is this?” The woman shook her head. “I don’t know. Do you think they’re moving us? I don’t know.” Analia bit her lip. Her fingers were numb.

She wanted to put her hands in her pockets, but she was afraid to move. Across the yard, Renata Kesler stood perfectly still. Her face was blank. She had learned in the past weeks that showing emotion was dangerous, so she buried it. She made herself a stone, but inside her mind raced. Is this an interrogation? A selection? Are they separating us? She had heard that word before, selection.

It had meant something terrible in the camps in the east. She did not know if it meant the same thing here. She did not want to find out. The American officers arrived quietly. No fanfare, no announcement. Captain Thomas Mercer stepped into the yard with a medic beside him. He wore a clean uniform. His boots were polished.

His face was tired but neutral. He carried a clipboard behind him. Sergeant Dorson stood with his rifle slung over his shoulder. He did not point it at anyone. He did not need to. His presence was enough. Nurse Lieutenant Mary Callahan followed a few steps behind. She carried a canvas medical bag. Her expression was calm, professional.

To the women in the yard, they looked like judges. Captain Mercer walked slowly along the first row. His boots made soft sounds in the dirt. He did not speak. He simply looked at each woman as he passed. He paused in front of one, wrote something on his clipboard, moved on. The woman he had paused in front of began to tremble.

Hanalor watched from three rows back. Her throat felt tight. She could not swallow. What is he writing? What did he see? Mercer reached the end of the first row. He turned, walked down the second. The silence was unbearable. Somewhere behind Hanalore, a woman started to cry, soft, muffled. She was trying to stay quiet, but the sound carried anyway. No one told her to stop.

Then the order came. Mercer stopped in front of Walt Linderman. He looked at her for a long moment. Then he spoke. His voice was not loud, not harsh, but it cut through the cold air like a blade. Open your coat. Three words in English. Walroud understood English. She had learned it in school years ago, but for a moment her brain refused to process the meaning. She stared at him.

He repeated it slower this time. Open your coat. Her hands moved to the buttons, but they would not obey. Her fingers were stiff, frozen, not from the cold, from fear. Behind her, the other women had heard the command. Even those who did not speak English understood the gesture Mercer made, a simple motion with his hand, mimming the opening of a coat. Analisa felt her knees weaken.

She grabbed the arm of the woman next to her to stay upright. Alfreda Roth closed her eyes. She thought she might be sick. Troutworth’s lips moved silently. A prayer, a plea she did not know anymore. This was the moment they had been warned about. This was the moment the propaganda had described.

The moment the whispered stories had promised, the moment when control was taken, when dignity was stripped, when the war stopped being about nations and became about bodies. Renata Kesler felt something break inside her chest. Not pain, something worse. resignation. This is it, she thought.

This is what happens now. Walroud finally opened her coat. Her hands shook as she unbuttoned it. She pulled the fabric apart. Beneath it, she wore a thin gray shirt. It hung loose on her frame. She had lost weight. They all had. She stood there exposed, waiting. Corporal Hartley, the medic, stepped forward.

He looked at her, not at her face, but at her torso, her collarbone, her arms. He made a note, nodded to the nurse. Then he moved to the next woman. Open your coat. The command repeated row by row, woman by woman. Some obeyed immediately, others hesitated. One woman tried to close her coat again after opening it.

Sergeant Dawson stepped forward, not threatening, but firm. The order was given again. She complied. Hanalor’s turn came. She had watched it happen to 15 women before her. She had seen the medic’s eyes. She had seen him write notes. She had seen women pulled aside and led toward a tent at the edge of the yard.

She did not know what happened in that tent. When Mercer stopped in front of her, she did not wait for the command. She opened her coat. She stared straight ahead. She did not look at him. She did not look at the medic. She looked at the gray sky and made herself disappear inside her own mind.

Hartley glanced at her, wrote something, moved on. Hanalore closed her coat. Her hands were shaking so badly she could barely fasten the buttons. The inspection continued one by one, methodically without emotion. The women stood. The officers moved. The clipboard filled with notes. And in the cold morning air, fear turned into something sharper. Certainty.

They had been right to be afraid. They had been right to believe the warnings. And now, whatever came next. There was nothing they could do but wait. What the women saw was humiliation. What the medics saw was something entirely different. Corporal James Hartley had been an army medic for 2 years.

He had treated gunshot wounds in foxholes. He had amputated limbs in field hospitals. He had seen men die from infections that started as small cuts. He was 24 years old and he was tired. When Captain Mercer briefed him the night before, the instructions were clear. We’ve got a health crisis in the women’s section.

Mercer had said, “Respiratory infections, possible tuberculosis, malnutrition. We need a baseline screening fast.” Hartley nodded. He had expected this. Every prisoner camp he had worked in faced the same problems. Too many people, not enough food, not enough warmth, disease spread quickly in conditions like that.

Check for visible signs, Mercer continued. Weight loss, skin infections, frostbite, anything that needs immediate treatment. We can’t afford an outbreak. It was not about control. It was about containment. The medical reality was grim. By spring 1945, prisoner camps across occupied Germany were overwhelmed.

The Allied advance had been faster than expected. Hundreds of thousands of German soldiers and auxiliaries had surrendered in a matter of weeks. The infrastructure could not handle the numbers. In the women’s section of the camp near the Rine, more than 1,200 women were housed in space designed for 400.

They slept on the ground. They shared blankets. They had no access to showers or proper latrines. Within two weeks, 12 women had developed pneumonia. Six had died. The camp physician, a French army doctor named Lauron Bowmont, had reported the deaths to command. His message was blunt. Without immediate medical intervention, we will lose more.

These women are starving. They are freezing. They are sick. We must act now. That report led to the order. The inspection was not punishment. It was triage. What Hartley looked for was specific. When a woman opened her coat, he scanned her quickly, professionally. He looked at her collarbone.

If it jutted out sharply, it meant severe weight loss. He looked at her hands. Blackened fingertips meant frostbite. He looked at her neck and face. Pale, waxy skin could indicate tuberculosis or anemia. He looked at her posture. If she swayed or struggled to stand, it meant exhaustion or illness. He did not look at her as a woman.

He looked at her as a patient, and what he saw again and again horrified him. While Trout Linderman had lost nearly 15 kg, Hartley could see it immediately. Her shirt hung loose, her belt was cinched tight, and still her trousers sagged, her cheekbones were sharp, her eyes were sunken. He made a note.

“Severe malnutrition requires supplemental rations,” he signaled to nurse Callahan. She stepped forward and handed Waltrod a wool blanket. Waltrod stared at it. She did not understand. “Take it,” Callahan said gently in broken German. “For you,” Waltroud took the blanket. Her hands trembled.

Three women down the line hardly found frostbite. Alfreda Roth had wrapped her hands in strips of cloth. When he asked her to remove them, she hesitated. Then she obeyed. Her fingers were mottled, dark red and purple. Two of her fingernails had turned black. Hartley’s jaw tightened. This was advanced.

She had been hiding it for days, maybe weeks. She needs treatment, he said to Callahan. Now Alfreda was pulled gently from the line. She did not resist. She was too weak. As she was led toward the medical tent, the other women watched in silence. They did not know what it meant. They only knew she had been taken.

The clipboard filled with notes, possible TB, isolated cough, night sweats, infected wound, left shoulder, needs cleaning and bandage, edema in legs, sign of starvation, lice infestation to requires dousing, respiratory distress, priority case. Hartley moved down the rose, one woman after another. His pen never stopped.

By the time he reached Hanalor Voit, he had flagged 22 women for immediate medical attention. Hanalor opened her coat. Hartley glanced at her, paused. She was thinner than she should be, but not dangerously so. No visible wounds, no signs of infection. Her breathing was steady. He made a brief note. Moved on.

Hannal stood there a moment longer, confused. That was it. That was all. The screening took 40 minutes. When it was finished, Captain Mercer dismissed the women back to their tents. But 17 of them were held back, not for punishment, for treatment. They were taken to a medical tent at the edge of the compound. Inside, CS had been set up.

There were blankets, a small stove, bandages, and disinfectant. Nurse Callahan moved between them, checking pulses, listening to lungs, cleaning wounds. One woman, a young signals assistant named Analisa Faulk, had been coughing blood for 3 days. She had not told anyone. She was terrified that if she appeared weak, something worse would happen.

Now she lay on a cot wrapped in two blankets while Callahan pressed a stethoscope to her chest. “Breathe,” Callahan said softly. “Anelise obeyed. Callahan frowned. She wrote something on a chart and handed it to Hartley.” pneumonia, he said. She needs antibiotics and rest. Anala’s eyes filled with tears, not from fear, from relief.

Slowly, understanding began to spread. The women, who had been examined, but not held back, returned to the barracks. They spoke in whispers. They didn’t do anything, one said. They just looked. They gave Wal a blanket. They took Alfreda to a tent, but I saw her through the flap. She was lying down. They were wrapping her hands.

It was medical, Renati Kesler said quietly. It was a medical inspection. The woman next to her stared. You sure? Renata nodded slowly. I think so. It was not cruelty. It was not humiliation. It was care. And that realization, that simple, quiet realization shattered something inside them.

Not their fear, but their certainty. That night, the barracks felt different. The cold was the same. The hard ground was the same. The rough wool blankets and the smell of damp canvas, all the same. But something had shifted. The women did not sleep right away. They sat in small clusters, speaking in voices barely above whispers.

The conversations were careful at first, hesitant, as if saying the words out loud might break whatever fragile truth they had discovered. Hanalor Voit sat near the tent flap, her diary balanced on her knee. She had not written anything yet. She did not know how to describe what had happened. She had expected violence.

She had received a glance. She had expected cruelty. She had received a clipboard note. It made no sense, and yet it had happened. The first whispers were questions. “Did they hurt anyone?” a young woman asked from across the tent. No, Renata Kesler answered. They didn’t touch anyone. Not like that.

But they took people away to the medical tent. Walroud Linderman said. Her voice was steady, firm. I saw it. They were treating wounds, giving blankets, checking for sickness. Silence followed. Then another voice, quieter. Why? No one had an answer. For some, belief came slowly. Troutworth sat in the corner, her blanket wrapped tight around her shoulders.

She had not spoken since returning from the yard. Her face was pale, her hands still trembled. She wanted to believe what the others were saying, but years of warnings echoed louder than one morning of mercy. They are the enemy, she thought. Enemies do not help. Enemies do not heal. She remembered the posters, the broadcasts, the stories whispered by neighbors and repeated by officials.

The Americans are no different from the Soviets. They will take what they want. They will show no mercy. And yet she had opened her coat. The medic had looked. He had written something. He had moved on. He had not smiled. He had not leared. He had not reached for her. He had simply done his job.

Alfreda Roth returned to the barracks the next morning. Her hands were wrapped in clean white bandages. Her color was better. She had been given hot soup and allowed to sleep in a heated tent. When she entered, the other women stared. She stood in the doorway unsure what to say. “They treated you?” Waltroud asked. Alfreda nodded.

“The nurse cleaned my fingers. She said too might be saved.” “The others?” She paused. “The others might not.” But she was kind. She was careful. They didn’t hurt you. Alfreda shook her head. No, they gave me medicine and bread. Real bread. The words hung in the air. Real? It was such a small thing and yet it meant everything.

Anala Fal remained in the medical tent for three more days. Her pneumonia was serious. She needed rest and medication. Nurse Callahan checked on her every few hours, adjusting her blankets, bringing water, listening to her lungs. On the second day, Analisa asked a question she had been afraid to ask.

Why are you helping me? Callahan looked at her. Her expression was tired but gentle. Because you are sick, said Sim. And I am a nurse. Analisa did not know how to respond. In her mind, she was still the enemy, a German, a member of the losing side, a prisoner. But Callahan did not treat her like an enemy.

She treated her like a patient. Later, Analisa would write about that moment in a letter to her mother. I thought they would see me as something less than human. Instead, they saw me as someone who needed help, and they helped me. I do not understand it, but I am grateful. Back in the barracks, the conversations grew bolder.

Women who had been silent for days began to speak. They shared what they had seen, what they had felt, what they had expected versus what had actually happened. Renato Kesler listened carefully. She had always been an observer, a collector of details, and what she observed now was a slow unraveling, not of fear.

Fear still lingered, but of certainty. The certainty that had been built over years, the certainty that the enemy was evil, that capture meant suffering, that mercy was impossible, that certainty was cracking. One woman spoke the words that many were thinking. Her name was Bridgete.

She was older than most, perhaps 30. She had been a civilian secretary attached to a logistics unit. She sat near the center of the tent, her arms crossed, her face lined with exhaustion. We were lied to, she said. The tent went quiet. All those stories, she continued. All those warnings, they told us the Americans were monsters.

They told us to fear them more than death. She shook her head slowly. But look at us. We are still here. We are still alive. They examined us like doctors. They fed us like people. She paused. Either everything we were told was wrong. Or this is some kind of trick. Waltroud spoke. It is not a trick. I have seen tricks.

This was not one. Bridget looked at her. Then what was it? Walroud thought for a long moment. Procedure sin. Just procedure. They have rules. They followed them. It was not a grand answer, not a comforting one, but it was honest. Hanalor finally wrote in her diary that night. She sat by the dim light of a single candle stub, her pen moving slowly across the page.

Today I learned that not all enemies are the same. Today I learned that fear can lie louder than truth. I do not know what tomorrow will bring, but I know this. The war I was taught to expect is not the war I am living through and I do not know what to believe anymore. She closed the diary. Outside the camp was quiet.

The guards walked there round. The stars were hidden behind clouds. And somewhere in the medical tent, Analisa Faulk slept peacefully for the first time in weeks. Years passed. The camps closed. The women went home. But the memory of that morning stayed with them. Not as trauma, not as victory, but as a question they could never fully answer.

Why had they been so afraid of something that never happened? Hanalor Voit returned to Bavaria in late 1945. Her family home was damaged, but standing. Her mother wept when she walked through the door. Her father sat in silence, unable to speak. She did not tell them everything. Some things were too hard to explain, but she kept her diary.

And decades later, when historians began collecting testimonies from women who had served in the war, she shared it. In one entry written months after her release, she reflected on the inspection in the yard. I have thought about that morning many times. I have asked myself why I was so certain something terrible would happen, and I have realized the answer.

I was not afraid of what I saw. I was afraid of what I had been taught to see. The enemy in my mind was far worse than the enemy in front of me. The others scattered across the ruins of Germany. Renata Kesler settled in Frankfurt. She worked as a translator for the Allied occupation government.

The irony was not lost on her. The same language she had once feared now paid her wages. She married in 1948, had two daughters, never spoke about the war until she was in her 70s. When she finally did in an interview for a university archive, she said something that surprised even her. The Americans were not kind to us because they liked us.

They were not cruel because they hated us. They simply followed their rules. And their rules said we were prisoners, not victims. That distinction saved us. It was a clinical observation, but it carried weight. Rules, procedure, systems. These were not words of warmth, but they were words of survival.

Valtrad Linderman never fully recovered. The war had taken too much from her. Her brother had died on the Eastern Front. Her fiance had disappeared somewhere near Stalingrad. Her health had been broken by months of malnutrition and cold. She lived quietly in a small town near Hamburg. She worked in a bakery.

She never married, but she remembered the blanket, the one Nurse Callahan had handed her in the yard, the one she had not understood at first. She kept it for years, long after the wool had thinned and the edges had frayed. It was not valuable. It was not beautiful, but it was proof. Proof that in the worst moment of her life, someone had seen her suffering and chosen to help.

Alfreda Roth lost two fingers to frostbite. The doctors at the camp had tried to save them, but the damage was too severe. By the time she was released, her right hand was permanently scarred. She learned to write with her left. She became a school teacher in a village near Munich. She taught children to read and write and add numbers.

She never told her students about the war. But sometimes when they asked about her hand, she would pause. An accident, she would say. A long time ago, it was easier than explaining. easier than describing the cold, the fear, the moment when an American medic had looked at her ruined fingers and said, “We’ll do what we can.

They had done what they could.” It had not been enough to save her hand, but it had been enough to save her life. Anala Faulk recovered from pneumonia. She spent 2 weeks in the medical tent before being transferred to a proper hospital. By the time she was released, the war had been over for months.

She returned to her parents’ farm in the countryside. She helped with the harvest. She married a neighbor’s son in 1950. She had four children. She lived until 2003. In her final years, she spoke often about the war, not with bitterness, not with pride, but with something closer to wonder. “I was 19 years old,” she said in one interview.

“I thought I was going to die in that camp. I thought the Americans would do terrible things to us. Instead, they gave me medicine and soup and a warm bed. I have never forgotten that. I never will. The statistics tell a larger story. Of the more than 80,000 German women held in Allied prisoner camps in Western Europe, the vast majority survived.

Mortality rates were low compared to other theaters of the war. Medical care, while limited, was provided. Food, while scarce, was distributed. This was not paradise. The camps were cold and crowded. Conditions were harsh. Mistakes were made. But the systematic brutality the women had been taught to expect did not occur.

The propaganda had lied. Fear leaves a long shadow. That is perhaps the deepest lesson of this story. Not that the allies were saints. They were not. Not that war is anything but brutal. It is. But fear, irrational, cultivated, weaponized fear, can distort reality beyond recognition. The women in that yard believed they were about to be violated.

They believed it because they had been told to believe it for years by their own leaders through posters and broadcasts and whispered warnings. And when the moment came, when the order was given, they could not see what was actually happening. They saw monsters. They saw threats. They saw the enemy of their imagination.

What they did not see, not at first, was a medic with a clipboard doing his job. The war ended. But the lesson remains. Sometimes the most terrifying moments are not acts of cruelty. They are moments of uncertainty. Moments when we do not know what comes next. And sometimes what comes next is not what we feared.

Sometimes it is simply human beings following rules, treating prisoners as patients, offering blankets instead of blows. It is not heroic. It is not dramatic. But it is real. And in the end, reality, not propaganda, is what survives. In the cold yard of an Allied prisoner camp, a simple order shattered years of fear. Open your coat.

Three words. A moment of terror. And then nothing. No violence. No cruelty, just a medic’s glance and a nurse’s blanket. The women who stood in that line had been taught to expect the worst. They had been fed propaganda designed to terrify. And when the moment came, they could not see the truth in front of them.

But truth does not need belief to exist. It simply waits. And sometimes, in the strangest places, and the in the mud of a prisoner camp, in the silence of a medical inspection, truth finds a way to be seen. This was not propaganda. This was reality. And for the women who lived it, that reality became something they carried for the rest of their lives.

A reminder that fear can lie and that even enemies sometimes can be human.

News

“‘Clean This Properly!’ the CEO Roared 😠 — Completely Unaware That the Man in Tattered Clothes Was Keanu Reeves in Disguise, Seconds Before a Corporate Meltdown, a Hidden Takeover Plot, and a Twist So Ruthless and Deliciously Cinematic Erupted That Executives Nearly Fainted From Shock 🏢🔥” Witnesses swear the CEO’s smug bark curdled into sheer panic when the ‘janitor’ lifted his head, triggering whispers of secret audits, undercover missions, and a karmic ambush years in the making

The Man Behind the Rags: A Shocking Revelation In the bustling heart of the city, where ambition thrived and dreams…

“LUXURY STORE ERUPTION 💎 Arrogant Socialite Hurls a Snide Insult at Sandra Bullock—Only for Fictional Keanu Reeves to Deliver a Breathtaking, Ice-Cold Reaction That Stops the Entire Boutique in Its Designer-Heeled Tracks 😱” — In this sparkling fictional meltdown, diamonds aren’t the only things cutting deep as Keanu’s silent glare slices through the tension, leaving the smug woman trembling while stunned shoppers cling to their pearls and gasp for emotional oxygen👇

The Jewel of Deceit In the heart of Beverly Hills, where glamour and wealth intertwine, a lavish jewelry store stood…

Keanu Reeves’ Secret Letter to Diane Keaton — The Quiet Confession That Sat Unread for Years and Rewrote a Hollywood Myth 💌 The narrator leans in with a sly hush as envelopes, dates, and a single sentence ignite whispers of restraint, timing, and a truth never meant for headlines, suggesting the real scandal wasn’t romance but the discipline to let love stay unclaimed until the moment passed forever

The Line Drawn: A Story of Missed Connections In the dazzling realm of Hollywood, where the glow of fame often…

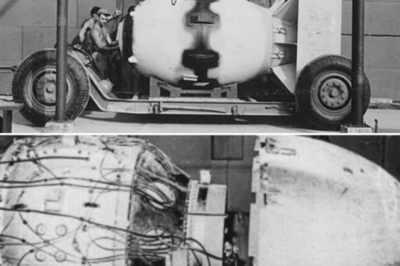

HOW FAT MAN WORKS ? | Nuclear Bomb ON Nagasaki | WORLD’S BIGGEST NUCLEAR BOMB

On August 6th, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The bomb was…

Why This ‘Obsolete’ British Rifle Made Rommel Change Tactics Uncategorized thaokok · 21/12/

April 1941, the Libyan desert outside Tobrook, Owen RML watched his panzas advance toward the Australian defensive perimeter, confident his…

“Inside the Ocean Titanic Recovered: After 80 Years, the Titanic Reassembled Piece by Piece — What They Found Will Shock You!” After 80 years submerged, the Titanic has been fully recovered and reassembled piece by piece, and what experts discovered during the process is far more shocking than anyone could have imagined. Hidden inside the wreckage were cryptic messages, unexplained artifacts, and eerie signs of the ship’s final moments. The Titanic’s restoration reveals a deeper, darker story than we’ve ever been told. The truth about the ship’s fate will haunt you forever

Echoes from the Abyss: The Resurrection of Titanic In the depths of the Atlantic, where shadows linger and whispers of…

End of content

No more pages to load