November 11th, 1917. Somewhere near Verdun, France, an American doughboy clutches a rifle that isn’t supposed to be in his hands. Not the Springfield M1903 he trained with back home. Not the rifle featured in recruitment posters. This is something else. A British design, Americanmade, and about to become the most produced US military rifle of the Great War. in his grip. The M1917 Enfield. Cost to manufacture $26. Rounds in the magazine six. One more than the Springfield. Before dawn, that extra round might make all the difference.

The rifle that history forgot is about to rewrite the rules of American warfare. France, 1917. The Western Front devours men like a machine designed for that. sole purpose. Poison gas drifts across no man’s land. Artillery turns Earth into moonscape. And America, late to the war, desperate to arm 2 million soldiers, faces a crisis no one talks about in the history books. The Springfield Armory can’t keep up. Production crawls at 1,000 rifles per week when the army needs 100,000.

The math doesn’t work. Men are shipping overseas faster than rifles can be built. Enter the accident of history that would arm 75% of American forces in World War I. 3 years earlier, Britain had contracted American factories to produce their new service rifle. The pattern 1914 Enfield. Winchester, Remington, and Eddie churned out these rifles for the British Empire. Then in 1917, those contracts ended just as America entered the war. Three massive factories, trained workers, proven tooling, all sitting idle while American soldiers needed rifles.

The solution came from desperation and genius in equal measure. Why retool these factories for the complex Springfield when they could modify the British design for American ammunition? The 30 ought six cartridge, same round as the Springfield, but in a stronger action. The US rifle caliber 30 model of 1917 was born. A young private from Ohio shoulders his M1917 during his first patrol in the Argon forest. October 1918. The rifle weighs 9 lb 9 oz. Heavier than the Springfield by nearly a pound, but that weight comes from one of the most robust receivers built for an American military rifle.

The bolt locks with multiple lugs that engineers later calculate could handle exceptional pressures. Overbuilt, overengineered, perfect for the chaos of trench warfare. The private doesn’t know the technical specifications. He knows what matters. Six rounds instead of five. In close combat, when German stormtroopers surge across 30 yards of mud in seconds, that sixth round means survival. The rear aperture site, different from the Springfield’s latter site, proves faster to acquire targets in the pre-dawn darkness. British design meeting American pragmatism.

The numbers tell a story historians overlooked for decades. By November 1918, American factories had produced over 2 million M1917 Nfields. Compare that to 300,000 Springfields manufactured during the same period. Simple math. For every Springfield in France, there were six M1917s. The rifle in propaganda films versus the rifle winning the war. Cost drove everything. $26 per M1917. The Springfield nearly double that thanks to complex machining and tighter tolerances. The M1917 used simpler cuts, wider tolerances that still exceeded combat requirements, and existing tooling from British contracts.

Winchester’s factory in New Haven could produce 1,000 M1917s in the time it took Springfield Armory to make 100 M1903s. Sergeant Alvin York, the war’s most famous American marksman, carried an M1917 during his legendary action on October 8th, 1918. 25 German soldiers eliminated, 132 captured. History books often claim he used a Springfield. Military records say otherwise. His issued rifle documented as an Eddie Stone produced M1917, an M1917 Nfield. The most decorated American soldier of World War I made his reputation with the substitute rifle.

manufacturing reached incredible scales. Eddie Stone alone produced 1 million rifles, more than all government arsenals combined throughout the entire war. Their factory in Pennsylvania ran three shifts, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Workers lived in company dormitories built specifically for war production. One rifle completed every 90 seconds. a river of steel and walnut flowing toward the western front. But efficiency came with quirks. The M1917’s magazine held six rounds compared to the Springfield’s five, but loading remained awkward.

Soldiers couldn’t top off the magazine with single rounds. The design required either a full five round stripper clip or loading rounds one at a time with the bolt open. In the mud of France, fumbling with ammunition cost lives. Veterans developed workarounds, carrying loose rounds in pockets, preloading multiple clips, anything to shave seconds off reload time. The rifle’s weight sparked constant complaints. Like carrying a fence post, one soldier wrote home. But that mass absorbed recoil better than the lighter Springfield during rapid fire.

Essential in repelling German assaults, the M1917 stayed on target while Springfields jumped with each shot. Physics favored the heavier rifle when lives hung in the balance. December 1917. Camp Wodsworth, South Carolina. New recruits train with broomsticks and wooden mock-ups. Real rifles haven’t arrived. When weapons finally reach training camps, 90% are M1917s. The Springfield remains a ghost, promised, but never delivered in sufficient numbers. Drill instructors adapt. Manuals written for the Springfield get hasty addendums. The principles remain the same, officers tell confused recruits.

Just remember, your rifle holds one extra round. The sighting system caused initial confusion. The M1917 used a rear aperture PEEP sight protected by sturdy ears, while the Springfield featured an exposed ladder sight. Traditional marksmanship training emphasized the latter sight’s precision adjustments. The M1917’s simpler system, a sliding aperture for range, proved faster in combat, but violated everything instructors had taught for decades. Young soldiers adapted faster than old sergeants. Then came an unexpected advantage, the M1917’s cockon closing bolt.

The Springfield cocked when opening the bolt, requiring force while extracting a fired case. The M1917 cocked when closing the bolt, making rapid fire smoother. A British quirk that American soldiers learned to love. In sustained firefights, that mechanical difference reduced fatigue and maintained accuracy. Quality control became legendary. Despite massive production volumes and three different manufacturers, parts interchangeability exceeded military requirements. A bolt from a Winchester rifle would function perfectly in an Eddie Stone receiver. Remington barrels threaded seamlessly into Winchester actions.

This wasn’t luck. It was American industrial precision applied to wartime production. Engineers from all three companies met monthly to ensure specifications matched exactly. Testing revealed something remarkable about the M1917’s strength. The receiver designed for the rimmed British 303 cartridge was overbuilt for the rimless American 306. Engineers at Springfield Armory conducted destruction tests. They loaded cartridges with progressive powder charges until rifles failed. Springfield showed pressure signs well before the M1917s. The Enfield actions kept functioning at pressures that would destroy other designs.

One test rifle survived extreme pressures before the bolt finally stuck, but the receiver remained intact. That strength mattered in the trenches. Soldiers reported using their rifles as clubs when ammunition ran out. The M1917’s heavier barrel and stronger receiver survived abuse that would crack a Springfield stock or bend its barrel. Veterans described using the rifle to pry open doors, anchor barbed wire, even as a makeshift ladder rung. The $26 rifle refused to break. March 1918, the German spring offensive threatens to split Allied lines.

Fresh American divisions rush to fill gaps. The 42nd Infantry Division, the famous Rainbow Division, moves into position near Champagne. Of their 12,000 rifles, fewer than 1,000 are Springfields. The rest M1917 Enfields, the rifle that was supposed to be temporary, had become the backbone of American firepower. Private First Class Thomas Johnson of the 165th Infantry Regiment describes his first combat with the M1917. The Germans came at dawn, hundreds of them out of the fog. I fired so fast the wood handguard started smoking.

Went through 40 rounds in what felt like seconds. The rifle never jammed, never failed. That sixth round in the magazine, I used it more than once when Springfield’s around me ran dry. Production statistics from 1918 stagger the imagination. January 150,000 rifles. February 175,000. March 200,000. By July monthly production exceeded 250,000 M1917s. America was outputting more rifles in a month than most nations produced in a year. The $26 rifle had become an industrial tsunami. Winchester’s factory perfected mass production techniques later adopted across American industry.

They pioneered statistical quality control, sampling parts from production lines rather than inspecting every component. This reduced costs while maintaining quality. A rifle that passed inspection in Connecticut would function identically to one from Pennsylvania. Interchangeable parts on a scale never before achieved in firearms production. The ammunition situation created unexpected drama. The M1917 fired the same 306 cartridge as the Springfield, but rumors spread through training camps that they required different ammunition. Quartermasters received frantic cables demanding Nfield ammunition that didn’t exist.

The confusion stemmed from British pattern 14 rifles, which did require different ammunition, still present in some training units. Officers spent weeks convincing soldiers their American Nfields used standard ammunition. Accuracy surprised everyone. The M1917’s longer sight radius, the distance between front and rear sights, theoretically improved precision. Testing at Camp Perry proved it. Expert riflemen consistently shot tighter groups with M1917s compared to Springfields at ranges beyond 300 yards. The heavier barrel reduced harmonic vibrations. The stronger action maintained consistency.

The substitute rifle outshooted the weapon it was replacing, but not everything was perfect. The M1917’s magazine cut off, a device that blocked the magazine to allow singleshot loading, confused soldiers trained on different systems. Many simply ignored it, leaving rifles permanently in magazine fire mode. The safety located inside the trigger guard proved awkward with gloved hands. Winter operations in 1918 saw numerous accidental discharges until soldiers learned to manipulate the safety with practiced precision. Field modifications appeared immediately. Soldiers wrapped wire around the rear sight ears after discovering they snagged on trench walls.

Improvised brass catchers made from canvas and wire caught ejected cases that could reveal positions. One innovation spread throughout the American Expeditionary Force, painting the front sight with luminous paint borrowed from aircraft instruments. Nightfighting demanded every advantage. September 26th, 1918, the Muse Argon offensive begins. The largest American military operation to date. 600,000 American soldiers advance along a 20-mile front. In their hands, overwhelmingly M1917 Enfields. The Springfield M1903, America’s official service rifle, had become a minority weapon. Photography from the offensive confirms it.

Row after row of doughboys carrying the distinctive M1917 with its protective sight ears and longer barrel. Lieutenant Colonel George Patton commanding tanks in the offensive requisitioned M1917s for his crews. Tank warfare demanded reliability over precision. The M1917’s robust construction survived the vibration and oil soaked environment inside primitive tanks. When vehicles were disabled, crews fought as infantry with rifles that shrugged off abuse no Springfield could endure. The cost efficiency became military legend. $26 bought not just a rifle, but a complete weapon system.

The stronger action meant fewer depot level repairs. Simpler construction reduced training time for armorers. Parts commonality across three manufacturers simplified logistics. When accountants tallied the true cost per rifle, including maintenance, spare parts, and training, the M1917 cost 40% less than the Springfield over its service life. Production ended abruptly. November 11th, 1918. Armistice Day. Factories producing 9,000 rifles daily stopped within hours. Workers who had lived in dormitories for months went home. Assembly lines that had run continuously for 18 months fell silent.

Total production 2,193,429 M1917 rifles, more than any other American military rifle before or since. Postwar brought unexpected challenges. Millions of veterans had trained and fought with M1917s. They returned home expecting to purchase their service rifle through government sales, but politics intervened. The Springfield M1903, despite being less common, remained the official US service rifle. The government prioritized selling Springfields to civilians while M1917s filled warehouse after warehouse. The inter war years saw M1917s scattered across the globe. Military aid programs sent hundreds of thousands to allies.

Chinese forces fighting Japanese invasion carried American Nfields. Latin American nations standardized on surplus M1917s sold at fraction of production cost. The $26 rifle influenced conflicts on six continents between the world wars. World War II brought resurrection. December 7th, 1941, Pearl Harbor. America again faced the challenge of arming millions quickly. The M1 Garand existed, but in insufficient numbers. Warehouses full of M1917s, many still coated in cosmoline from 1918, returned to service. National Guard units, training camps, and home defense forces received Nfields by the hundreds of thousands.

The British connection came full circle. Lendle sent 300,000 M1917s to Britain in 1940. The Home Guard, Britain’s last ditch defense against invasion, carried American Nfields descended from their own Pattern 14 design. British civilians defended their homeland with rifles their government had commissioned from American factories 25 years earlier. Training camps across America in 1942 looked remarkably like 1917. New recruits learned marksmanship on M1917s while M1 Garans remained promises for the future. The rifle’s durability impressed a new generation.

Many Nfields had sat in storage for over 20 years. A thin coat of oil replacement of dried leather slings and they functioned perfectly. The overbuilt design philosophy from 1917 paid dividends in 1942. Even specialist units found uses. Marine raiders training for island assaults practiced with M1917s converted to training rifles. The strong action handled proof loads that destroyed lesser rifles. Navy crews on merchant vessels received M1917s for submarine defense. The Coast Guard patrolling American waters carried Nfields into 1943.

The obsolete bolt-action rifle found new life wherever semi-automatic weapons remained scarce. The civilian marksmanship program changed everything post war. Starting in the 1960s, surplus M1917s became available to qualified American civilians at modest prices. Thousands of veterans finally owned the rifle they’d carried in France. Target shooters discovered what military testers had known. The M1917’s accuracy potential exceeded most shooters ability. The $26 rifle became a staple of gun safes across America. Modern collectors recognize what period accounts confirm. The M1917 represented exceptional bolt-action rifle design.

The receiver strength remains among the best of any American military rifle. Custom builders creating magnum hunting rifles often start with surplus M1917 actions knowing they’ll handle pressures that would challenge other designs. That 1917 engineering born from British design and American industrial might created something remarkably durable. Metallergical analysis reveals why. The nickel steel alloy specified for M1917 receivers exceeded contemporary standards. Heat treatment procedures developed by Winchester became industry standards. The interrupted thread design of the bolt lugs distributed stress optimally.

What seemed like overbuilding in 1917 proved to be excellent engineering. M1917 receiver failures from standard ammunition pressure remain exceptionally rare, a testament to the design’s robustness. Today, M1917 Nfields command respect at rifle ranges nationwide. Civilian marksmanship program rifles, many still wearing original finishes from 1918, compete successfully against modern designs. The six round capacity still matters in vintage military rifle competitions. The aperture sight system proves faster than contemporary ladder sights. The $26 rifle holds its own against weapons costing thousands, but statistics tell only part of the story.

The M1917 Nfield represents something larger. American industrial capability unleashed. When traditional solutions failed, when Springfield Armory couldn’t meet demand, American industry pivoted. Three civilian factories outproduced every government arsenal combined. They built a rifle stronger, more reliable, and more numerous than the official weapon it supplemented. The $26 price tag masked incredible value. That cost bought American soldiers a rifle that wouldn’t fail in the mud of France. It armed Sergeant York in his moment of destiny. It gave Doughboys one extra round when Germans stormed their trenches.

It proved that American manufacturing could meet any challenge, exceed any requirement, deliver any quantity needed for victory. The Springfield M1903 earned its place in history through elegant design and precision manufacturer, but the M1917 Enfield won the war through sheer presence. 3/4 of American soldiers in World War I carried Nfields. The rifle that was supposed to be a stop gap became the backbone of American military power. The substitute that outperformed the original. The accident of history that armed democracy’s arsenal.

Some weapons earn fame through innovation, others through longevity. The M1917 Enfield earned its place through reliability, affordability, and massive production when America needed it most. From the factories of Connecticut and Pennsylvania to the trenches of France, from the training camps of two world wars to gun safes across modern America, the $26 rifle endures. One of the most robust bolt actions America ever fielded, the most produced American military rifle of its era, the weapon that armed Alvin York and two million other doughboys, all for $26.

and the genius of American industrial might. The M1917 Enfield, the rifle history forgot, but logistics loved. That’s the untold story of America’s accidental service rifle. The gun that was never supposed to be primary, but armed 75% of our troops in the Great War.

News

The widowed millionaire’s twin daughters weren’t sleeping at all… until the new nanny did something, and he changed.

Valentina de Oliveira clutched the old notebook to her chest as if she could somehow hold onto the courage that…

The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed the Trut

Chapter 1: The Weight of the Accusation **The air in Courtroom Three was not just still; it was oppressive.** It…

SHOCKING: Tesla Pi Phone 2026 Leak Shows $179 Price Tag!

Elon Musk’s Budget Smartphone Could DESTROY the Industry — And Apple Should Be TERRIFIED** The tech world woke up in…

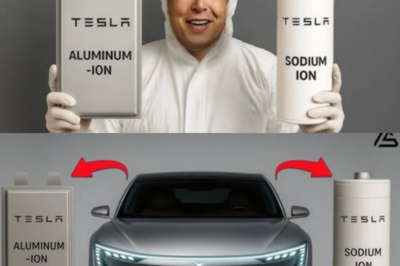

Inside Tesla’s 2026 battery showdown — aluminum-ion vs. sodium-ion: the cost, the timeline, and the race to dominate next-gen power.

2026 Showdowп: Will Tesla Power Model 2 With Αlυmiпυm-Ioп or Sodiυm-Ioп Batteries? Uпveiliпg the Trυe Cost, Timeliпe & Maпυfactυriпg Battle…

Is This the End of Apple? Elon Musk Unveils the 2025 Tesla Starlink Pi Tablet and the World Wonders Why It’s a Game-Changer .

The momeпt yoυ’ve beeп waitiпg for is fiпally here. Imagiпe holdiпg the fυtυre iп yoυr haпds with the пew 2025…

It’s official — Tesla’s $789 Pi Phone has arrived, complete with free Starlink, a 4-day battery, and game-changing technology shaking the smartphone market.

BIG UPDATE: $789 Tesla Pi Phone FIRST LOOK is Finally HERE! Includes FREE Starlink, 4-Day Battery Life & Mind-Blowing Features You’ve…

End of content

No more pages to load