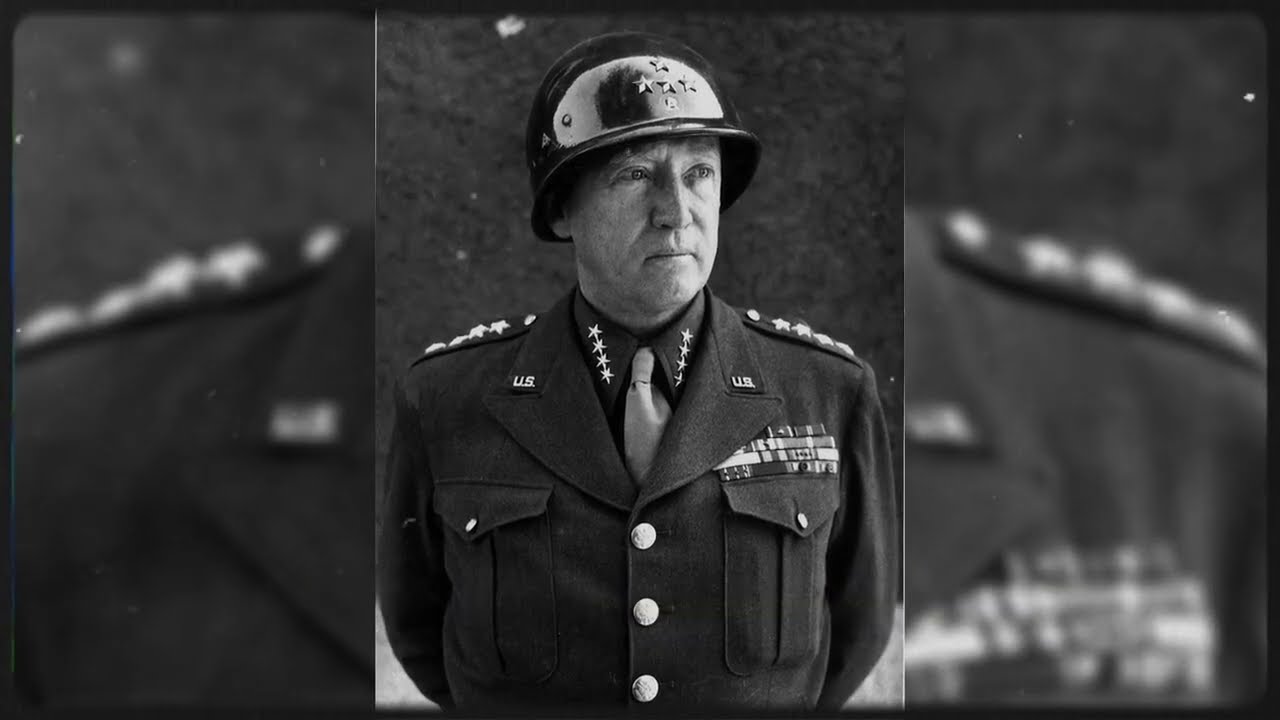

December 21st, 1945. Winston Churchill is at Chartwell, his country estate, when the telegram arrives. General George S. Patton Jr., America’s most feared combat commander, is dead. Churchill reads the telegram once, then twice. He sets it down on his desk, lights a cigar, and stares out the window for a long moment.

When he finally speaks to his secretary, his words aren’t flowery. They aren’t diplomatic. They’re blunt, brutal, and absolutely revealing. What Churchill says in that moment and in the days that follow exposes a truth that Britain’s wartime leader rarely admitted in public, that America had produced something Britain no longer could.

a general of pure ruthless aggression. The kind of commander who won wars not with elegance but with speed and violence. And now that weapon was gone, just as the world was entering its most dangerous peace. If you want the raw, unfiltered truth about history’s greatest figures, hit that subscribe button now because what Churchill said about Patton will shock you.

To understand Churchill’s reaction, you need to understand what Patton represented to him. Churchill had spent six years fighting a war that had nearly destroyed Britain. The empire was bankrupt. Cities were rubble. An entire generation of young men had been killed or maimed. And by 1945, Britain was exhausted in a way that’s hard to comprehend today.

Churchill knew, though he rarely admitted it publicly, that Britain could no longer win wars on its own. The days of British military dominance were over. America was now the dominant partner in the alliance. American industrial might, American manpower, and increasingly American military leadership were what would shape the post-war world.

And among American generals, Patton stood apart. Churchill had watched Patton’s campaigns across North Africa, Sicily, France, and Germany. He’d seen what Patton could do when unleashed, drive armies forward at speeds that seemed impossible, exploit breakthroughs that more cautious commanders would consolidate, and simply overwhelm the enemy through relentless aggression.

It was a style of warfare that Churchill admired because it was a style Britain once practiced back when the empire was young and hungry and willing to be ruthless. So when the telegram arrived at Chartwell announcing Patton’s death from injuries sustained in a car accident, Churchill understood immediately what had been lost. Churchill secretary, Elizabeth Leighton, was present when he received the news.

Years later, she described his reaction in her memoir. Churchill read the telegram silently, then said, “Patton’s dead.” Just two words: flat. Matter of fact, Leighton waited, knowing Churchill would say more. “Damn shame. Damn bloody shame. The man survives four years of war. North Africa, Sicily, France, Germany, and dies in a car accident in peace time.

There’s a cruel irony in that. He paused to light his cigar and then said something more revealing. The Americans don’t realize what they’ve lost. Not yet, but they will. This wasn’t the Churchill of stirring speeches and poetic phrases. This was the private Churchill, the strategist who understood military power in cold, practical terms.

Later that evening, Church Hill drafted a formal condolence message to President Truman and to Patton’s widow. The message was appropriately solemn, praising Patton’s courage and leadership. But it was what Churchill said off the record to his military chiefs, to his closest adviserss, to the few people he trusted with his unfiltered thoughts that reveals what he really believed about Patton.

The next day, Churchill met with Field Marshal Alan Brookke, his chief of the Imperial General Staff and closest military adviser throughout the war. Their conversation was recorded in Brook’s private diary, which wasn’t published until decades later. According to Brooke, Churchill began by asking, “What did you think of Patton?” Brooke, never one to mince words, replied, “Brilliant tactician, hopeless diplomat, a 19th century cavalry officer who happened to command tanks instead of horses.” Churchill nodded.

“Yes, precisely, and that’s exactly what made him invaluable.” Then Churchill said something that cuts to the heart of his view. “We don’t produce generals like that anymore, Allan. We can’t afford to. We produce careful, competent commanders who coordinate with allies, who consider political implications, who fight wars the modern civilized way.

But Patton, Patton fought wars the way wars have always been won with speed, shock, and ruthless exploitation of enemy weakness. Brookke pointed out that Patton had caused endless political problems, the slapping incidents, inflammatory statements, conflicts with other commanders. Of course, he did. That’s the price of having a weapon like Patton.

He was a weapon, you understand? Not a diplomat, not a politician. A weapon. And like any weapon, he needed to be pointed in the right direction andcontrolled. But when you needed someone to break through enemy lines and drive 300 miles in two weeks, there was no one better. Then Church Hill said something remarkable.

The tragedy isn’t that America has lost patent. The tragedy is that we never had a patent of our own. Not in this war, anyway. This admission reveals something Churchill rarely acknowledged. Britain’s military leadership in World War II was fundamentally different from the kind of aggressive, risk-taking leadership Patton embodied.

British generals like Montgomery were careful, methodical, focused on minimizing casualties because Britain simply couldn’t afford the losses. After the slaughter of World War I, British military culture had become cautious almost to a fault. American generals, especially Patton, didn’t have those constraints. America had the manpower, the industrial capacity, and the willingness to accept casualties in exchange for rapid victory.

Churchill understood this dynamic perfectly. In a conversation with Anthony Eden, his foreign secretary, Churchill was even more explicit. Patton could do things Montgomery couldn’t dream of doing. Not because Montgomery wasn’t brilliant. he was. But because Montgomery commanded a shrinking army of an exhausted nation, every British casualty mattered.

Every decision had to be weighed against what we could afford to lose. Patton commanded an expanding army of a nation that was just getting started. He could take risks we couldn’t take. He could drive forward when we had to consolidate. He could accept casualties that would have been politically impossible for us.

Then Churchill added, “And that’s why his death matters more than people realize. America thinks it has dozens of generals like Patton. It doesn’t. It has one, and now it has none.” Churchill kept returning to this idea of Patton as a weapon. It came up in multiple private conversations during the weeks after Patton’s death.

To one aid, Churchill said, “The Americans are sentimental about their generals. They want to believe their commanders are both brilliant and lovable. But war isn’t about being lovable. War is about destroying the enemy’s will to fight. And Patton understood that better than anyone.

Churchill elaborated, “When you needed to break the Gustav line, you called on careful preparation and overwhelming force. When you needed to coordinate a massive amphibious invasion, you called on meticulous planning. But when you needed to race across France faster than the enemy could regroup, when you needed to relieve Baston in 48 hours, when you needed someone who would simply refuse to accept that something was impossible, you called on Patton.

He was a weapon, Churchill continued, a difficult weapon, a weapon that needed constant maintenance and caused endless headaches, but a weapon of tremendous power. And weapons like that don’t come along often. In another conversation, Church Hill made the military calculus even clearer. The question isn’t whether Patton was difficult to manage.

The question is whether his results justified the difficulty. And the answer is obviously yes. The man drove from Normandy to the German border faster than anyone thought possible. He relieved Baston when everyone else said it couldn’t be done. He crossed the Rine with such speed that the Germans couldn’t organize a defense.

Those are the kinds of results that win wars. But Churchill’s most revealing comments about Patton came when he started thinking about the future, specifically about the Soviet Union. By December 1945, Churchill was already deeply worried about Soviet expansionism. He’d seen Stalin consolidate control over Eastern Europe.

He’d watched Soviet forces refuse to withdraw from territories they’d occupied, and he was increasingly convinced that the West would soon face a new kind of conflict with its former ally. This is where Churchill’s assessment of Patton becomes truly profound. In a conversation with his private secretary, Churchill said, “You know what? The Soviets respected force, decisiveness, commanders who were willing to be ruthless.

They respected Patton because Patton scared them. Not because of what he’d done, but because of what he was capable of doing. Churchill continued, “The Soviets understood Patton in a way they never understood Eisenhower or Bradley. Patton was a threat, a credible immediate threat, the kind of general who might actually attack if provoked, and that’s valuable even in peace time, especially in peace time.

” Then Churchill added something chilling. We’re entering a period where wars won’t be fought directly. They’ll be fought through threats, through demonstrations of strength, through making your adversary believe you’re willing to go further than they are. And Patton was the perfect weapon for that kind of war. His mere existence was a deterrent.

He paused, then added, “And now he’s gone, just when we need that kind of deterrent most.” In a particularly candid momentwith Field Marshall Montgomery, who’d had his own famous clashes with Patton, Churchill articulated something that must have been difficult for the British leader to admit.

Bernard Churchill said, “I know you and Patton didn’t get along. I know he was arrogant, insubordinate, and impossible to work with at times, but here’s what you need to understand. In 50 years, when historians write about this war, they’re going to remember Patton more than any British general, except perhaps yourself.

And they’re going to remember him not despite his aggression, but because of it. Montgomery started to object, but Church Hill continued. Britain won this war through endurance, through refusing to surrender when all seemed lost, through building alliances and coordinating with partners. Those are admirable qualities, but they’re not the qualities that inspire future generals or frighten future enemies.

Patton’s aggression, that ruthless, relentless drive forward, that’s what people will remember, that’s what people will fear. Churchill then made his point explicit. We need to be honest with ourselves. Britain no longer produces generals like Patton because we no longer fight wars the way Patton fought them. We can’t afford to.

We’re a declining power managing our decline with dignity and skill. America is an ascending power that hasn’t yet learned the limits of its strength. And Patton embodied that perfectly. All that raw, unrefined power with no real understanding of limits. Now that power is gone, Churchill concluded, and I’m not sure America realizes what it’s lost.

Perhaps Churchill’s most complete assessment of Patton came in a letter he wrote to Field Marshall Yan Smutz of South Africa, one of his closest confidants throughout the war. The letter was personal and wasn’t intended for publication. In it, Church Hill wrote, “The news of Patton’s death has affected me more than I expected. Not because I knew the man well, our actual interactions were limited, but because I recognized what he represented, a type of military leadership that history rarely produces, and that the modern world increasingly finds uncomfortable.

Patton was unsuited for peaceime. He was politically tonedeaf, socially awkward outside military circles, and constitutionally incapable of the kind of diplomatic nuance that peaceime requires. But in war, he was magnificent. He understood something that most modern generals have forgotten, that wars are won not by careful accumulation of advantages, but by sudden, overwhelming applications of force at decisive moments.

The Americans will miss him, though they may not realize it yet. They will look for another Patton and will not find one because men like Patton emerge from a particular combination of temperament, training, and historical moment. That moment has passed. The age that produced cavalry officers who could transition seamlessly to commanding armored divisions is over.

Church Hill concluded, “We have lost a warrior in an age that will increasingly be managed by administrators, and I fear we will miss such warriors sooner than we think.” On December 21st, 1945, George Churchill learned that George Patton was dead. His response wasn’t sentimental. It wasn’t poetic. It was the cold assessment of a strategist who understood what had been lost.

Britain no longer produced generals like Patton, men of pure aggression and relentless drive. Because Britain could no longer afford such generals. America had produced one. And now, as the world entered an uncertain peace with the Soviet Union, that weapon was gone. Churchill understood something that many didn’t.

Patton’s value wasn’t just in what he accomplished during the war, but in what he represented going forward. He was a deterrent, a threat, the kind of general who made adversaries think twice before pushing too hard. Without Patton, the post-war balance of power shifted slightly. Not enough that anyone noticed immediately, but enough that Churchill, with his strategic mind and his understanding of how power actually works, recognized the loss.

Whatever Patton’s flaws, and they were many, he was irreplaceable. Not because there weren’t other competent generals, but because there weren’t other generals willing to be that aggressive, that relentless, that unconcerned with comfort or convention. Churchill carried that recognition with him into the Cold War, and history would prove him right.

The world would miss Patton’s particular brand of ruthless competence more than anyone realized at the time. If this changed how you see Churchill and Patton, smash that like button and drop a comment. Was Church Hill right about Patton being irreplaceable? And don’t forget to subscribe. We’re uncovering the brutal truths behind history’s greatest figures every single week.

News

Jesus’ Tomb Opened After 2000 Years, What Scientists Discovered Shocked the Entire World

In a groundbreaking development that has sent shockwaves around the globe, scientists have opened Jesus Christ’s tomb for the first…

BREAKING NEWS: Keanu Reeves once revealed what makes him happy—and fans say it’s the purest answer ever ⚡

Keanu Reeves Once Revealed What Makes Him Happy—and Fans Still Call It the Purest Answer Ever Keanu Reeves has starred…

BREAKING NEWS: Keanu Reeves shares romantic kiss with Alexandra Grant in rare NYC date night moment

Keanu Reeves Shares Passionate Kiss With Girlfriend Alexandra Grant—and Fans Say, “Love Looks Exactly Like This” Keanu Reeves doesn’t chase…

BREAKING NEWS: Ana de Armas reveals how Keanu Reeves helped her survive Hollywood’s toughest years

Ana de Armas Opens Up About Her “Beautiful Friendship” With Keanu Reeves—and Becoming an Action Star by Accident Standing onstage…

I came home late after spending time with a sick friend, expecting the night to be calm and uneventful. Instead, something unexpected happened at home that quickly changed the mood. I chose not to react right away and took a moment to step back. What I did next quietly shifted the dynamic in our household and made everyone pause and reconsider things they had long taken for granted.

I didn’t know yet that this would be the last night I walked into that house as a mother. All…

When my marriage came to an end, my husband explained what he wanted to keep, including the house and the cars. My lawyer expected me to fight back, but I chose a calmer path and agreed to move forward peacefully. Friends were confused by my decision. What they didn’t understand at the time was that this choice was made carefully—and its meaning only became clear later.

It started on a Tuesday. I remember the smell of the floor cleaner—synthetic lemon, sharp and slightly bitter—because I had…

End of content

No more pages to load