April 1941, the Libyan desert outside Tobrook, Owen RML watched his panzas advance toward the Australian defensive perimeter, confident his armor would punch through within hours. By nightfall, 17 of his 38 tanks lay wrecked or burning in the sand. The assault collapsed, not because of one miracle weapon, but because the defenders had built a layered anti-tank trap, mines, two pounder guns, artillery firing direct, and smaller brutal weapons waiting for the vehicles the big guns did not waste time on. One of those

weapons weighed 36 lb, fired five rounds from a top-mounted magazine, and had been written off by military planners on both sides as incapable of stopping modern armor. The boy’s anti-tank rifle could not kill a Panza head on, but it could kill the things that kept panzas alive, and that mattered more than anyone expected.

The boy’s anti-tank rifle emerged from a problem that haunted British military planners throughout the 1930s. Tanks were getting stronger. Infantry had nothing to stop them. A rifleman watching a steel monster roll toward his position had precisely two options: run or die. The War Office demanded a solution that individual soldiers could carry, that could punch through armor at combat ranges, and that cost far less than deploying anti-tank guns to every infantry platoon.

Captain Henry Charles Boy of the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield took on the challenge in October 1934 under the classified code name Stansion. Boy understood the fundamental physics. To penetrate armor, you needed velocity. To achieve velocity from a portable weapon, you needed a carefully balanced cartridge that maximized muzzle energy without destroying the shooter’s shoulder. He settled on a.

55 in caliber, 13.9 mm. The original Mark1 ammunition pushed a 60 g bullet at 747 m/s. By December 1939, the improved MK2 round had replaced it, driving a lighter 47 g projectile at roughly 884 m/s. Later in the war, engineers experimented with tungsten cord rounds, hoping to claw back relevance against thickening armor, but the fundamental limitation remained.At 100 yard, the round punched through 23 mm of armor plate at perpendicular impact. At 500 yd, that dropped to roughly 19 mm. Add any realistic combat angle, and penetration fell sharply further. Still enough to defeat lighter vehicles, nowhere near enough for medium tanks.

The weapon that emerged stretched 63 1/2 in long, required a two-man team to transport effectively, and featured a prominent muzzle brake and padded shoulder rest designed to absorb the punishing recoil. Captain Boy never saw his creation enter service. He died in November 1937, just days before the War Office weapon, they renamed it in his honor, though German intelligence documents consistently misspelled it as boys throughout the war.

Production began at Birmingham Small Arms, the Royal Small Arms Factory Enfield, and John English in Canada. By the time manufacturing ceased in autumn 1943, approximately 62,000 rifles had rolled off the assembly lines, a massive investment in a weapon that critics increasingly dismissed as worthless. Those critics were looking at the wrong targets.

The problem with calling the boys obsolete was that obsolescence depends entirely on what you are shooting at. Against the Panza 3 and Panza 4 variants that arrived in North Africa from 1941 onward, the rifle was genuinely useless. 50 mm of frontal armor laughed at 23 mm of penetration. British soldiers discovered this reality with grim finality.

One sergeant from the King’s Royal Rifle Corps described engaging a tank at 50 yards during the French campaign. The round struck perfectly. It knocked off the paintwork. The tank kept coming. He abandoned the rifle on the spot, but the western desert was not populated exclusively by Panzer 3s. RML’s Africa Corps operated alongside Italian forces equipped with armor that belonged to an earlier generation.

The L333 and L335 tankets carried armor between 6 and 14 mm thick. Well within the boy rifle’s capability. Heavier Italian tanks like the M1340 offered better protection and could resist frontal hits, but the tankets and armored cars that screened Axis advances remained vulnerable. And the Italians provided roughly half of Axis armored strength in the theater.

Beyond tanks entirely lay the softskin logistics that kept any army functioning. Fuel trucks, ammunition carriers, staff cars, armored cars like the German SDKFZ 222 with its 8 mm of protection. The boy’s rifle could destroy all of them from positions that heavier anti-tank guns could not reach.

When planners wrote off the weapon as obsolete, they forgot that modern warfare runs on petrol and bullets, not just panzas. The rifle proved itself before the desert campaign even began. In Norway during April 1940, Platoon Sergeant Major John Shepard of the First Fifth Battalion Leershir Regiment faced approaching German armor at the village of Treton.

According to widely attested accounts, he had neverfired a boy’s rifle before that morning. Working methodically, he put multiple armor-piercing rounds into each advancing tank. Two German panzas stopped permanently. The remainder withdrew. It remains one of the earliest recorded instances of British ground forces destroying German tanks in the Second World War.

A month later in France, Sergeant William Gilchrist of the Irish Guards held a street corner at Bologna for two hours with nothing but a boy’s rifle and determination. His documented award citation noted that he hit and set fire to an enemy tank, blocking the street and enabling his battalion to withdraw. He refused to abandon his position until the weapon jammed from continuous firing.

Now, before we see how this weapon shaped RML’s tactics in the desert, if you’re enjoying this deep dive into overlooked British engineering, hit subscribe. It takes a second, costs nothing, and helps the channel grow. Right back to North Africa. During Operation Compass in December 1940, the fourth sixth Raj Bhutana rifles and first North umberland fuseliers engaged Italian positions at Tamar East.

Unit records document two M1139 tanks and six trucks destroyed by boy rifle fire. The seventh Hous knocked out five Italian CV tankets in a single action. Contemporary accounts report that Private Oz Neil of the Australian forces destroyed three Italian tanks with his boy rifle. A feat that according to those accounts astounded everyone given the weapon’s growing reputation for uselessness.

Then came to Brooke. General Leslie Mohead organized his Australian defenders into a layered system designed to neutralize German armored superiority. The outer perimeter absorbed the initial tank assault while infantry kept their heads down. As panzas passed over the first defensive line, soldiers emerged to engage the following German infantry.

The second line deployed two pounder anti-tank guns and 25 pounders firing over open sights, the real tank killers. But threading through this entire system were boys rifle teams positioned to engage armored cars, light vehicles, and the reconnaissance elements, probing for weaknesses. On April 14th, 1941, RML launched his assault, expecting to break through within hours.

The combined defensive system shattered that expectation. 17 of 38 tanks wrecked or disabled. The attack withdrawn to Brook forced adaptation. The system did it. Not any single weapon, but the boy’s rifle filled gaps in that system, engaging targets the heavier guns ignored, contributing to the layered defense that taught German commanders hard lessons about underestimating British anti-tank coordination.

The weapon found its ultimate validation in the Pacific rather than Africa. At Mil Bay in Papua on August 27th, 1942, Corporal John Francis Patrick O’Brien of the Second 10th Infantry Battalion engaged Japanese Type 95 Hgo tanks attacking Australian positions. The Type 95 carried between 6 and 12 mm of armor, making it vulnerable to the supposedly obsolete British rifle.

O’Brien’s tank, perforated with multiple boys rounds, now sits at the Australian War Memorial with visible penetration holes, physical evidence preserved in steel. Days earlier at Meckin Island, United States Marine Corps raiders borrowed Canadian manufactured boys rifles for their assault. Two Japanese sea planes floated in the lagoon carrying reinforcements.

Boys rifle teams engaged from the shore. One sea plane erupted in flames. The second crashed, attempting takeoff after sustained hits shredded its hull. The weapon the Germans had dismissed as useless, had just conducted successful anti-aircraft operations. The Germans themselves recognized the rifle’s limitations and potential simultaneously.

Their equivalent, the Pansabuka 39, actually outperformed the boys with 30 mm of penetration compared to 23. Yet, German high command ceased production in November 1941, the same period British forces were supposedly handicapped by their obsolete rifle. Both nations recognized that anti-tank rifles could not defeat modern tank armor.

Only Britain continued finding alternative uses for the investment already made. Soldiers hated firing the boys. Australians called it Charlie the Bastard. The recoil caused neck strains, shoulder injuries, and occasional detached retinas, even with the padded stock and muzzle brake. The muzzle blast was so fierce that men were told to protect their hearing whenever possible.

Troops joked that firing the double nickel should automatically qualify a man for the Victoria Cross. A Canadian government training film produced by Disney in 1942 specifically addressed the weapon’s reputation as jinxed, attempting to restore confidence in an unpopular but still useful tool. The rifle disappeared from frontline service by mid 1943, replaced by the Pat, the projector infantry anti-tank.

But its legacy extended beyond its service life. 62,000 rifles represented 62,000 positions where infantry could engage armoredtargets without waiting for dedicated anti-tank gun support. In the Western Desert, that meant 62,000 potential threats to Italian tankets to access supply columns to reconnaissance vehicles probing defensive lines.

The weapon declared obsolete against the enemy it was designed to fight proved effective against the enemies it actually encountered. Tbrook taught German commanders that British forces would not accommodate their tactical preferences. A coordinated defense incorporating supposedly obsolete rifles alongside modern anti-tank guns and field artillery firing direct could disrupt armored assaults.

The system worked because every component filled a role. The boy’s rifle filled gaps the heavier weapons left open. The boy’s rifle did not win battles alone. No single weapon ever does, but it filled gaps that nothing else could fill. engaged targets that heavier weapons ignored and contributed to defensive systems that forced German commanders to rethink armored warfare.

62,000 rifles, 36 lb each, 23 mm of penetration at close range, officially obsolete against medium tanks, practically effective against everything else. The weapon that critics dismissed as useless now sits in museums from Canra to London, some still bearing the scars of combat. One particular type 95 tank in Australia carries holes that prove what the specification suggested and the veterans confirmed.

The boy’s anti-tank rifle worked, not always against what it was meant to fight, but always against something that needed killing. British engineering did not produce a perfect weapon. It produced a weapon that soldiers adapted to battlefield reality, finding targets its designers never anticipated and roles its critics never imagined.

That flexibility, that stubborn refusal to abandon a tool simply because it failed at its primary purpose defined British military pragmatism throughout the war. The rifle meant to stop tanks ended up stopping supply trucks, aircraft, tankets, and armored cars. It helped defend kill Japanese armor in the jungle and teach RML that wars are not won by panzas alone.

Obsolete is a word for peace time. In combat, there is only what works and what does not. The boy’s rifle worked.

News

“‘Clean This Properly!’ the CEO Roared 😠 — Completely Unaware That the Man in Tattered Clothes Was Keanu Reeves in Disguise, Seconds Before a Corporate Meltdown, a Hidden Takeover Plot, and a Twist So Ruthless and Deliciously Cinematic Erupted That Executives Nearly Fainted From Shock 🏢🔥” Witnesses swear the CEO’s smug bark curdled into sheer panic when the ‘janitor’ lifted his head, triggering whispers of secret audits, undercover missions, and a karmic ambush years in the making

The Man Behind the Rags: A Shocking Revelation In the bustling heart of the city, where ambition thrived and dreams…

“LUXURY STORE ERUPTION 💎 Arrogant Socialite Hurls a Snide Insult at Sandra Bullock—Only for Fictional Keanu Reeves to Deliver a Breathtaking, Ice-Cold Reaction That Stops the Entire Boutique in Its Designer-Heeled Tracks 😱” — In this sparkling fictional meltdown, diamonds aren’t the only things cutting deep as Keanu’s silent glare slices through the tension, leaving the smug woman trembling while stunned shoppers cling to their pearls and gasp for emotional oxygen👇

The Jewel of Deceit In the heart of Beverly Hills, where glamour and wealth intertwine, a lavish jewelry store stood…

Keanu Reeves’ Secret Letter to Diane Keaton — The Quiet Confession That Sat Unread for Years and Rewrote a Hollywood Myth 💌 The narrator leans in with a sly hush as envelopes, dates, and a single sentence ignite whispers of restraint, timing, and a truth never meant for headlines, suggesting the real scandal wasn’t romance but the discipline to let love stay unclaimed until the moment passed forever

The Line Drawn: A Story of Missed Connections In the dazzling realm of Hollywood, where the glow of fame often…

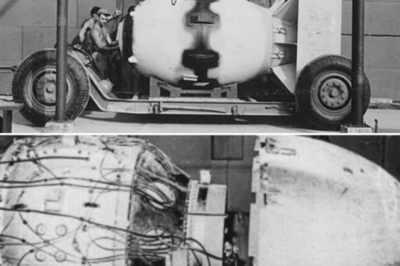

HOW FAT MAN WORKS ? | Nuclear Bomb ON Nagasaki | WORLD’S BIGGEST NUCLEAR BOMB

On August 6th, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The bomb was…

“Inside the Ocean Titanic Recovered: After 80 Years, the Titanic Reassembled Piece by Piece — What They Found Will Shock You!” After 80 years submerged, the Titanic has been fully recovered and reassembled piece by piece, and what experts discovered during the process is far more shocking than anyone could have imagined. Hidden inside the wreckage were cryptic messages, unexplained artifacts, and eerie signs of the ship’s final moments. The Titanic’s restoration reveals a deeper, darker story than we’ve ever been told. The truth about the ship’s fate will haunt you forever

Echoes from the Abyss: The Resurrection of Titanic In the depths of the Atlantic, where shadows linger and whispers of…

The SinkinThe Sinking of the IJN Shinano: A Tragic WWII Storyg of the IJN Shinano: A Tragic WWII Story

In the quiet pre-dawn blackness of November 28th, 1944, something immense slipped through the waters off the coast of Japan,…

End of content

No more pages to load